2

NEEDS ASSESSMENT

2.1 Overview of this Section

A needs assessment consists of the business analysis work that is conducted in order to analyze a current business problem or opportunity. It is used to assess the current internal and external environments and current capabilities of the organization in order to determine the viable solution options that, when pursued, would help the organization meet the desired future state.

This section of the practice guide offers a comprehensive approach for assessing business needs and identifying high-level solutions to address them. It provides ways to think about, learn about, discover, and articulate business problems and opportunities. Thinking through business problems and opportunities with stakeholders is important for all programs and projects; the degree to which a needs assessment is formally documented depends upon organizational and, possibly, regulatory constraints.

2.2 Why Perform Needs Assessments

In business analysis, needs assessments are performed to examine the business environment and address either a current business problem or opportunity. A needs assessment may be formally requested by a business stakeholder, mandated by an internal methodology, or recommended by a business analyst prior to initiating a program or project. As used in this practice guide, a project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result. A program is a group of related projects, subprograms, and program activities managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually.

Needs assessment work is undertaken before program or project work begins, therefore it is said to involve the preproject activities. However, during the course of a project, should external factors change (e.g., corporate merger, large percentage loss of market share etc.), which influence or impact the project in process, the business analyst will need to revisit the needs assessment and decisions made previously to ensure they are still valid for the situation the business is addressing.

A needs assessment involves the completion of a gap analysis—a technique described in Section 2.4.7—that is used to analyze and compare the actual performance of the organization against the expected or desired performance. Much of the analysis completed during the needs assessment is then used for the development of a business case. It is the needs assessment and business case that build the foundation for determining the project objectives and serve as inputs to a project charter.

When a needs assessment is bypassed, there is often insufficient analysis to adequately understand the business need. The business analyst conducts a needs assessment to help the organization understand a business problem or opportunity in greater detail to ensure that the right problem is being solved. When a formal needs assessment is sidestepped, the resulting solution often fails to address the underlying business problem or fails to solve the problem completely; it is also possible to provide a solution that is not needed or one that contains unnecessary features.

2.3 Identify Problem or Opportunity

Part of the work performed within needs assessment is to identify the problem being solved or the opportunity that needs to be addressed. To avoid focusing on the solution too soon, emphasis is placed on understanding the current environment and analyzing the information uncovered. The business analyst needs to ask “what problem are we solving?” or “what problems do our customers have that this opportunity will address?” The business analyst begins to elicit information to uncover the data necessary to fully identify the problem or opportunity.

2.3.1 Identify Stakeholders

Stakeholder identification is conducted as part of the needs assessment to assess which stakeholders are impacted by the area under analysis. A stakeholder is an individual, group, or organization that may affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a decision, activity, or outcome of a program or project.

For example, when an organization wants to take advantage of a new technology or plans to automate current manual processes, stakeholder identification is performed to identify who will be impacted by the changes. There are various ways to locate stakeholders. Some possible methods are described in Section 3 on Business Analysis Planning, where this topic is presented in more depth.

During needs analysis, it is helpful to identify the following stakeholders:

- Sponsor who is initiating and responsible for the project,

- Stakeholders who will benefit from an improved program or project,

- Stakeholders who will articulate and support the financial or other benefits of a solution,

- Stakeholders who will use the solution,

- Stakeholders whose role and/or activities performed may change as a result of the solution,

- Stakeholders who may regulate or otherwise constrain part or all of a potential solution,

- Stakeholders who will implement the solution, and

- Stakeholders who will support the solution.

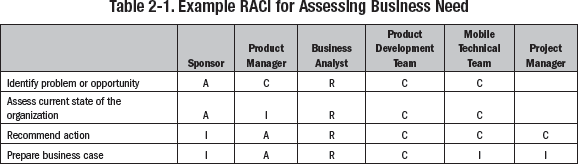

The affected stakeholders for a needs assessment can be categorized into one of four categories using a responsibility assignment matrix such as a RACI model:

- R—Responsible. Person performing the needs assessment,

- A—Accountable. Person(s) who approves the needs assessment, including the business case, when warranted,

- C—Consult. Person or group to be consulted for input to understand the current problem or opportunity, and

- I—Inform. Person or group who will receive the results of the needs assessment.

Example—Consider an insurance company that is interested in reducing the processing times and costs for automobile and homeowner claims. Initially, the organization understands the solution may impact a number of stakeholders across the company. To better understand who to involve in the needs assessment phase, the business analyst develops a RACI matrix to determine the roles and levels of responsibility.

Table 2-1 shows an example of a partial stakeholder list for the insurance company. Other possible stakeholders might be the claims operations manager, claims examiners, partners, and suppliers.

Collaboration Point—Both project managers and business analysts have an interest in stakeholder identification and RACI analysis. While the project manager is concerned about analyzing the roles across the project, business analysts may perform their analysis to a lower level of detail or may focus on one specific area, such as a needs assessment or requirements elicitation. Each may lend support to the other and work together to perform this work. It is important to ensure efforts are not duplicated.

2.3.2 Investigate the Problem or Opportunity

The business analyst focuses on learning enough about the problem or opportunity to adequately understand the situation, but avoids conducting a complete requirements analysis at this stage. As used here, situation is a neutral word to describe the context about the problem or the opportunity being investigated.

Initially, the business analyst may conduct interviews with stakeholders to investigate the situation and learn about the current environment. The business analyst may also review any existing documentation about current processes, methods, or systems that support the business unit. Process modeling is one technique used to document current “as is” processes of the business. The business analyst may monitor or observe the business performing their work in order to discover elements of the current “as-is” process. This technique is referred to as observation. For more information on observation, refer to Section 4 on Requirements Elicitation and Analysis.

2.3.3 Gather Relevant Data to Evaluate the Situation

Once a broad understanding of the situation is obtained, it is necessary to gather relevant data to understand the magnitude of the problem or opportunity (also known as “sizing up” the situation). The lack of data can result in proposing solutions that are either too small or too large compared to the problem at hand. In other words, the business analyst should attempt to measure the size of the problem or opportunity to help determine an appropriately sized solution.

When no internal data exists or when it cannot be feasibly collected, benchmarking may be performed. Benchmarking is a comparison of the metrics or processes from one organization against a similar organization in the industry that is reporting or finding similar industry averages. Data may not be readily available since competitors will guard nonpublic data closely. Benchmarking may also involve comparing internal organization units or processes against each other. Examples of data suitable for benchmarking include, but are not limited to the following:

- Cycle times for a business process to complete transaction volumes, occurrences of exceptions or problems, and delays caused by the exceptions or problems;

- Amount of money lost per transaction, per sale, by losing a customer, from costs to acquire a new customer, through waste, and from calls to a help desk;

- Website visitors, website conversions, sales inquiries, new accounts, and new policies;

- Potential increases in sales, market share, customer base, and new contracts;

- Market size, potential new market share, current competition, and pricing structures in place; and

- Competitive analysis of products offered, feature and benefit comparisons, pricing, and policies regarding the foregoing.

Once the desired data is assembled, techniques such as Pareto analysis and trend analysis can be used to analyze and structure the data.

2.3.4 Draft the Situation Statement

Once the problem is understood, the business analyst should draft a situation statement by documenting the current problem that needs to be solved or the opportunity to be explored. Drafting a situation statement is not time-consuming, but it is a very important step to ensure a solid understanding of the problem or opportunity the organization plans to address. If the situation statement is unknown, or wrong, or if the stakeholders have a different idea of the situation, there is a risk that the wrong solution will be identified.

The format of a situation statement is as follows:

- Problem (or opportunity) of “a”

- Has the effect of “b”

- With the impact of “c”

Example—Consider the insurance company example that was presented previously. Like many companies, this insurance carrier took advantage of new technologies across its business and has an extensive Internet presence. The organization now wants to exploit mobile technology to improve its claims processing.

Before the development of a project charter, the business analyst drafts a situation statement for inclusion in a formal business case. Using the knowledge gained through the initial needs assessment work, the business analyst considers the identified business need and any initial assessment of the impact that the problem is having on the business. With this background information, the business analyst can then draft the situation statement, such as:

“The cost for processing claims has been rising steadily, increasing at an average rate of 7% per year, over the last 3 years. The existing method for submitting claims either by phone or the Internet involves significant processing delays and has resulted in the need to increase staffing to process the calls and personally investigate the claims.”

The problem, as assessed, was one of increased costs to process claims, including additional labor costs.

Note: The financial impacts identified in the situation statement will later be referenced during the completion of the cost-benefit analysis.

2.3.5 Obtain Stakeholder Approval for the Situation Statement

Once the situation statement is drafted, agreement is obtained from the affected stakeholders that were previously identified. This is a key step because the situation statement guides subsequent work for assessing the business need. When a formal situation statement and its approval are skipped, it is difficult to determine whether the essence of the current situation has been captured. Business stakeholders play an important role to ensure that the situation statement correctly defines the situation. Failing to refine the situation statement with the business may result in a solution that addresses only part of the business need or fails to meet the business need at all.

The business analyst initiates and facilitates the approval process, which may be formal or informal, depending on the preferences of the organization. Approval may not occur upon the first review of the situation statement, and there may be a need to revise or reword the statement so that the stakeholders are in agreement with it. The business analyst leverages skills such as facilitation, negotiation, and decision making to lead stakeholders through this process.

2.4 Assess Current State of the Organization

Once the relevant stakeholders agree on the problem that needs to be solved or the opportunity the organization wishes to exploit, the situation is analyzed in greater detail to discover important components such as the root causes of the problems identified in the situation statement. As stated previously, the assessment is not a complete current state analysis. It is intended to understand current organizational goals and objectives, root causes of problems that prevent achievement of these, goals and/or any important contributors to opportunities that could help attain them.

2.4.1 Assess Organizational Goals and Objectives

Depending on the organization, business strategy documents and plans may be available for review by the business analyst in order to acquire an understanding of the industry and its markets, the competition, products and services currently available, potential new products or services, and other factors used in developing organizational strategies. In the absence of such plans, it may be necessary to interview stakeholders to determine this information.

The organizational goals and objectives are an important input used by the business analyst when they begin documenting the business requirements. Goals and objectives that are relevant to the situation provide the context and direction for any change or solution that addresses the business need.

Business requirements are goals, objectives, and higher-level needs of the organization that provide the rationale for why a project is being undertaken. Business requirements are defined before a solution is determined and recognize what is critical to the business and why. For additional information pertaining to business requirements, see Section 4 on Requirements Elicitation and Analysis.

2.4.1.1 Goals and Objectives

Organizational goals and objectives are often revealed in internal corporate strategy documents and business plans. Corporate strategies translate goals identified in business plans into actionable plans and objectives. Goals are typically broad-based and may span one or more years. Objectives, on the other hand, are used to enable goals; these are more specific and tend to be of shorter term than goals, often with durations of 1 year or less.

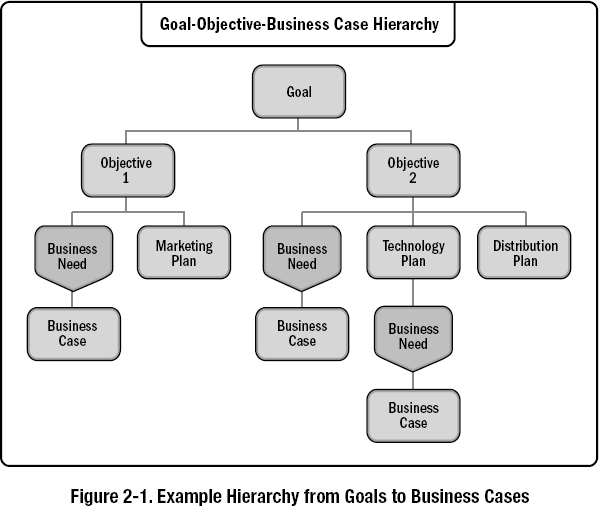

An organization accomplishes its objectives in various ways, including through programs and projects. The most common link between goals and objectives and programs and projects is the business case. Figure 2-1 shows an example of the hierarchical relationship between goals, where goals have one or more objectives and may have any number of business cases and various tactical plans to support them. The approved business cases are used as inputs to programs and projects. However, not all projects have a business case associated with them, but this section will focus on those that do.

Goal and objective modeling approaches are discussed in Section 4.10.7 on Scope Models.

2.4.1.2 SMART Goals and Objectives

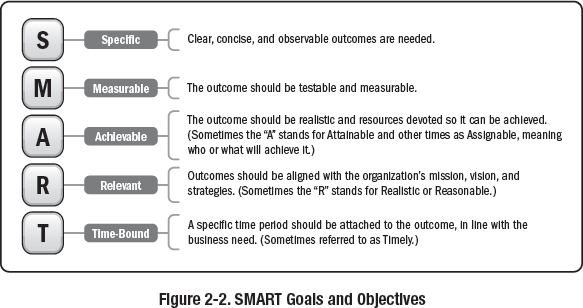

If goals and objectives are not specified or are not clear, the business analyst should document them to establish the basis for subsequent work that relies on them. Well-written goals and objectives are also said to be “SMART” as summarized in Figure 2-2. Note there are subtle variations for writing SMART goals and/or objectives; this example is one of the more common approaches used today.

Example—In the previous insurance company example, the insurance company had a goal of reaching $5 billion in revenue within 5 years, with a 20% net profit margin. The company also had the following supporting objectives for the coming year:

- Increase revenues by 10% by December 31 (necessary to help them reach their 5-year goal),

- Decrease overall claims costs by 5% in the same time period,

- Reduce time needed to process claims by 6.25% in each quarter of the year.

In summary, goals and objectives are important to needs assessment, because they provide the context and provide direction for any change that addresses the business need. Ideally, except for unforeseen problems and opportunities, all programs and projects directly support the stated business goals and objectives. Programs and projects are linked to the goal and objectives through the business case. Business cases are assembled as one of the final tasks in the needs assessment and are discussed in further detail later on in this section. Even without a formal business case, goals and objectives should be leveraged to guide the direction of business analysis.

2.4.2 SWOT Analysis

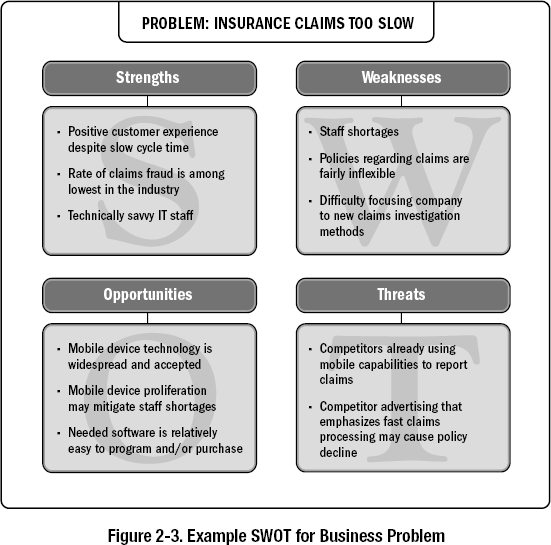

In the absence of formal plans, the business analyst may use SWOT analysis to help assess organizational strategy, goals, and objectives. SWOT (standing for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) is a common method used to facilitate discussions with stakeholders when articulating high-level and important aspects of an organization, especially as it pertains to a specific situation.

SWOT uses the four categories mentioned previously and provides an additional context for analyzing the business need. It helps to translate organizational strategy into business needs. SWOT investigates the situation internally and externally as follows:

- Internally:

- Shows where the organization has current strengths to help solve a problem or take advantage of an opportunity. Examples of strengths include a knowledgeable research staff, strong brand reputation, and large market share.

- Reveals or acknowledges weaknesses that need to be alleviated to address a situation. Weaknesses may include low recognition in the market, low capitalization or tax base, and bad publicity due to real or imagined failures.

- Externally:

- Generates potential opportunities in the external environment to mitigate a problem or seize an opportunity. Examples of opportunities include underserved markets, termination of a competitor's product line, and discovery of a customer need that the organization can satisfy with a new product.

- Shows threats in the market or external environment that could impede success in solving business needs. Threats may include increased market share by the competition, new products offered by competitors, mergers and acquisitions that increase a competitor's size and clout, and new regulations with potential penalties for noncompliance.

SWOT is a widely used tool to help understand high-level views surrounding a business need. The business analyst may use SWOT to create a structured framework for breaking down a situation into its root causes or contributors.

Example—Figure 2-3 shows a sample SWOT diagram for the insurance company example.

2.4.3 Relevant Criteria

Goals and objectives provide criteria that may be used when making decisions regarding which programs or projects are best pursued. When goals and objectives involve revenue generation, then programs or projects to expand markets or add new products are key. When one of the major objectives is to decrease costs, then programs or projects for process improvement or cost elimination are important.

Example—One objective of the insurance company is to increase revenues 10% by December 31. In this case, revenue is a highly relevant criterion. The organization needs to sell new insurance policies and possibly expand its markets; therefore, programs or projects that improve sales will be significant. Initiatives that support expense reduction are very important too because the company also needs to reduce expenses. Criteria that were identified when reviewing the organizational goals and objectives will be useful later when comparing and rank-ordering potential solution options.

2.4.4 Perform Root Cause Analysis on the Situation

Once a situation is discovered, documented, and agreed upon, it needs to be analyzed before being acted upon. After agreeing on the problem to be solved, the business analyst needs to break it down into its root causes or opportunity contributors so as to adequately recommend a viable and appropriate solution. For purposes of brevity, this practice guide will treat root cause analysis and opportunity analysis as one topic. To clarify these terms, each is defined as follows:

- Root Cause Analysis. An analytical technique used to determine the basic underlying reason that causes a variance, defect, or risk. When applied to business problems, root cause analysis is used to discover the underlying cause of a problem so that solutions can be devised to reduce or eliminate them.

- Opportunity Analysis. A study of the major facets of a potential opportunity to determine the viability of successfully launching a new product or service to enable its achievement. Opportunity analysis may require additional work to study the potential markets.

There are a number of techniques used to perform root cause and opportunity analysis, and most work for both. This practice guide presents the following common methods:

2.4.4.1 Five Whys

The objective of Five Whys is to ask for the cause of a problem up to five times or five levels deep to truly understand it. A business analyst does not always need to literally ask “why” up to five times. Instead, the Five Whys are used to begin with a problem and ask why it occurs until the root cause becomes clearer. Quite often, business people bring solutions to the project team, but it is essential to first clarify the business problem with a technique like Five Whys before considering solutions. Other techniques may be needed to refine the root cause, but Five Whys is a good starting point.

It is important to ask “why” using appropriate questions and to limit the actual use of the word “why,” because it can cause the interviewee to become defensive.

Example—In the insurance company example, a Five-Whys dialog might proceed as shown in Table 2-2.

2.4.4.2 Cause-and-Effect Diagrams

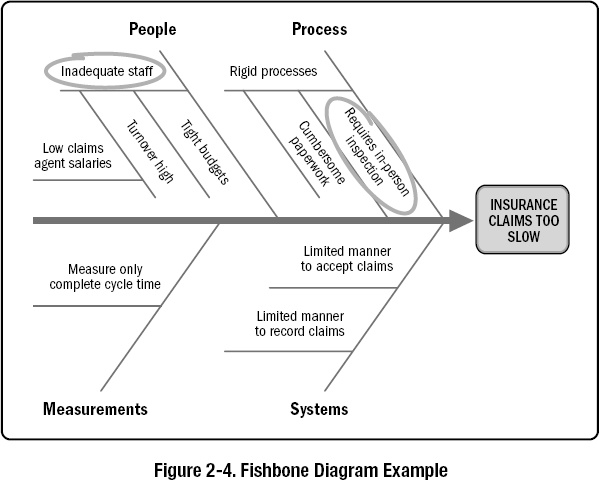

Cause-and-effect diagrams decompose a problem or opportunity to help trace an undesirable effect back to its root cause. These diagrams help to break down the business problem or opportunity into components to aid understanding and generally provide the main aspects of the problem to analyze. They are typically high-level views of why a problem is occurring or, in the case of an opportunity, these views represent the main drivers for why that opportunity exists. Cause-and-effect diagrams are designed to understand the cause of a problem so as not be distracted by its symptoms. These diagrams take a systems view by treating the environment surrounding the problems as the system and by avoiding analysis of the problems imposed by people or staff.

There are several types of cause-and-effect diagrams that could be used to uncover root causes. Most of these techniques can be used along with the Five Whys to dissect a problem. From a practical standpoint, it may be sufficient to go two to three levels deep in order to understand the needed elements of root cause. Two of the most useful cause-and-effect diagrams are described as follows:

Table 2-2. Sample Conversation Using Five-Whys Dialog

| Role | Question/Reply |

| Sponsor | We would like to add the ability for policyholders to submit claims from their mobile phones. We figure it would speed up claims processing considerably. |

| Business analyst | I'm new on this team. Can you help me to understand why this is a problem? [Why 1] |

| Sponsor | Well, the problem is that claims take too long to process. With a mobile application, we can encourage customers to file claims as soon as an accident or storm happens. Plus, there are other features of smart phones we can exploit, like using their cameras and video technology. |

| Business analyst | What do you think is the major delay in processing claims? [Why 2] |

| Sponsor | Partly it's the lag between the time of an incident and when the policyholder files a claim, which can add several days to a week to the process time. The delay also results from our corporate policy that we need to investigate every claim we think will exceed certain limits. That tends to be 80% of all claims. |

| Business analyst | Can you tell me the reason behind the need to investigate so many claims personally? [Why 3] |

| Sponsor | We're a pretty conservative company, and to avoid fraud, we like to personally view the damage. |

| Business analyst | What other alternatives for speeding up claims have you tried in the past, and why didn't they work? [Why 4] |

| Sponsor | Well, we tried skipping the investigation for all but the highest claim amounts, and our losses jumped way up. We also tried encouraging customers to call us on a dedicated line from their mobile phones. But for some reason they didn't seem to have our number handy or who knows completely why, but we didn't get enough calls to warrant continuing. |

| Business analysis analyst | What did you attribute the higher losses to? [Why 5] |

| Sponsor | We found out that many of the damages were not as bad as the claims indicated. I think we overpaid by around 20% if I remember correctly. |

- Fishbone Diagrams. Formally called Ishikawa diagrams, these diagrams are snapshots of the current situation and high-level causes of why a problem is occurring. These diagrams are often a good starting point for analyzing root cause. Fishbone diagrams lend guidance to the causes that will provide the most fruitful follow-up. For example, they often uncover areas in which data is lacking and would be beneficial to collect. However, this technique is not sufficient for understanding all root causes.

Note: Fishbone diagrams traditionally use the word “effect” because they are cause-and-effect diagrams. However, it could easily be a situation or problem instead.

There are various ways of depicting a fishbone diagram. Figure 2-4 shows one such rendition. Here are some guidelines for using fishbone diagrams:

- The problem to be solved is placed at the head of the fish, which can be either facing to the right or left.

- Use between three to eight causes or categories as an optimum number of causes associated with the problem. Standard categories, when used, can help guide the process and include machines, methods/systems, materials, measurements, people/customers, policies, processes/procedures, and places/locations.

- For each cause identified, ask why that cause is occurring and label any subcauses discovered. Generally, two to three levels will be sufficient to gain insights into the problem to understand its root causes.

- Look for patterns of causes, which are useful items to measure, model, or otherwise study in more detail. They are more likely to lead to the root cause of the situation. Circle those significant factors as shown in the example in Figure 2-4.

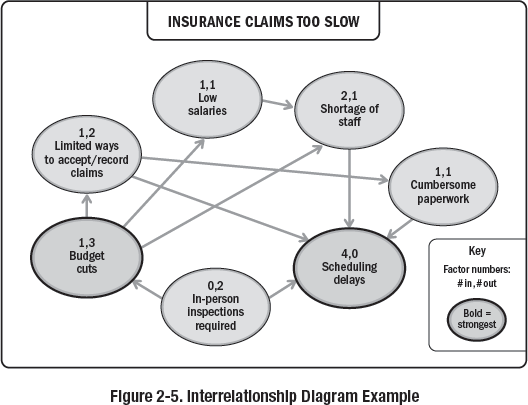

- Interrelationship Diagrams. This special type of cause-and-effect diagram is helpful for visualizing complex problems that have seemingly unwieldy relationships among multiple variables. These diagrams are most useful for identifying variables, but similar to the fishbone diagram, this technique is not sufficient for understanding all root causes. In some cases, a cause of one problem may be the effect of another. The interrelationship diagram can help stakeholders understand the relationships between causes and effects and can identify which causes are the primary ones producing the problem.

Constructing an interrelationship diagram helps participants isolate each dimension of a problem individually without it being a strict linear process. Focusing on the individual dimension allows participants to concentrate on and analyze manageable pieces of a situation. When the analysis is complete, the diagram sheds considerable light on the problem, but only after the entire diagram has been assembled.

Here are some guidelines for using interrelationship diagrams:

- Identify the potential causes and effects, up to a maximum of ten to be practical.

- Draw lines between the effects and their causes. The arrows represent the direction of the cause. The arrow starts from the cause factor and points to the effect. See Figure 2-5 and note the factor “budget cuts” and the causing factor “shortage of staff.”

- When two factors influence each other, understand which of the two is stronger and note which one. Interrelationship diagrams are most effective when arrows are limited to one direction, namely the stronger influence.

- Factors with the largest numbers of “incoming” arrows are those that are key outcomes of other factors, that is, effects. These often provide good measures of success or can be good items to quantify and monitor. In Figure 2-5, “scheduling delays” is shown to be the most significant effect.

- Factors that have a large number of “outgoing” arrows are the sources of the problem, that is, causes. Label the factor numbers in and out. In Figure 2-5, “budget cuts” is shown to be the most significant cause. Consider prioritizing needs assessments to address the strongest causes first.

- The significant cause and effect factors can be depicted in bold to emphasize them as in the example in Figure 2-5.

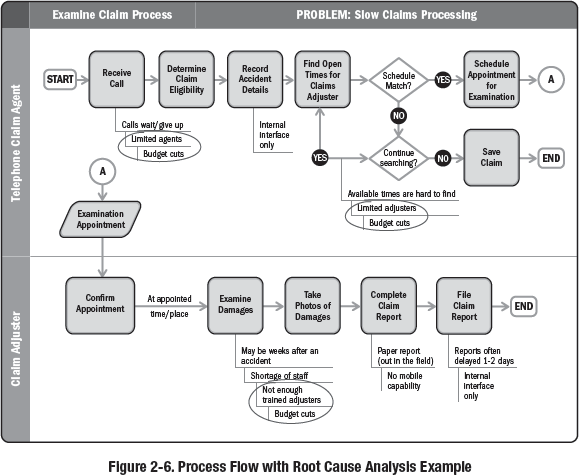

- Process Flows. Process flows are used for many things, primarily to document and analyze current and future (e.g., proposed) processes. Another use for these models is to analyze a process for the ways in which a current process contributes to a given problem. In this sense, a process flow can be used as a root-cause analysis tool. A nonoptimal process existing in the current as-is environment may have gaps or missing steps, duplication, or unnecessary and non-value-added steps. Process flows are not useful when analyzing opportunities.

Process flow modeling can be used in conjunction with root cause analysis as it focuses on how aspects of current processes may contribute to the problem at hand. In the insurance company example, the scheduling limitations for the in-person inspections are a major contributor to the current situation. Figure 2-6 is an example of a process flow that is used for root cause analysis. Some guidelines for using process flows for problem analysis include:

- Select the situation and place it at the top of the process map to emphasize the problem to be solved. Here it will remain highlighted.

- Identify the steps in the process that result in the problem. Try and keep the number of steps at a high level, often around ten or fewer steps.

- For each step, ask how that step may be contributing to the identified problem. For each cause, probe to find any subcauses and add them in a similar fashion to a fishbone diagram. Figure 2-6 shows a cause of “available times are hard to find,” with a subcause of “limited adjusters,” and a root cause of “budget cuts.”

- Look for steps that have several issues as the best places to find changes or improvements, or perform further investigations to verify and/or measure. Circle the factors that are felt to be significant causes and subcauses of the problem being assessed. Figure 2-6 shows one repeating factor that was noteworthy.

Process flows are described in more depth in Section 4 on Requirements Elicitation and Analysis.

2.4.5 Determine Required Capabilities Needed to Address the Situation

Once the root causes or contributors to a situation are known, the methods to correct them and/or take advantage of opportunities can be specified. For simple process improvement situations, it may only be necessary to recommend process changes without adding new capabilities or other resources.

For more complicated situations and for opportunities, new capabilities may be needed, such as, software, machinery, skilled staff, or physical plants or properties. The business analyst will recommend suitable capabilities based on discoveries made during the root cause analysis or based on the concepts and contributors to success that were identified when analyzing an opportunity.

Various methods exist for determining new capabilities. When formal root cause analysis is not performed, business people may “jump to solutions” to solve their perceived problems. The result is often adding new capabilities that address only part of a situation and may also be more expensive than needed.

2.4.5.1 Capability Table

By examining each problem and the associated root causes, a needed capability can be discovered. One tool to help facilitate this analysis is a capability table, where the business analyst lists each limiting factor or problem, specifies the associated root causes, and then lists the capability or feature required to address the problem.

Capabilities may also be represented in a visual model like a feature model, see Section 4.10.3 for more information.

Example—Table 2-3 provides a capability table for the insurance company example.

Table 2-3. Capability Table Example

| Problem/Current Limitations | Root Cause(s) | New Capability/Feature |

| Insurance claims too slow | Limited claims agents | • Additional trained agents • Higher pay for claims agents |

| Necessity for in-person inspections | • New policy for skipping examinations based on insured's policy length, claim history, and initial intake interview • Use of insured's technology to record damage |

|

| Limited claims adjusters | • Additional trained adjusters • See Section 2.2 |

|

| Reports delayed | Limited ways to accept/record claims and reports | • New methods of accepting claims • Submit reports remotely |

| Paper reports | • Eliminate paper reports |

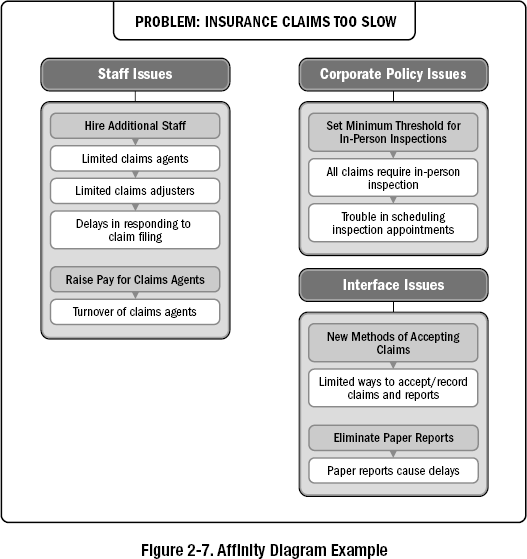

2.4.5.2 Affinity Diagram

Another method for determining capabilities is to use an affinity diagram. Affinity diagrams show categories and subcategories of ideas that cluster or have an affinity to each other. For problem solving, an affinity diagram is used to help organize and structure major cause categories and organize them by the capabilities needed to solve them.

Affinity diagrams are used for multiple purposes. These are handy for drawing out common themes when faced with several disparate and potentially unorganized findings. These diagrams can be used to help connect related issues of a problem or opportunity. They can also provide insights into collections of factors to help understand root causes and possible solutions to problems. The latter point makes them useful for generating the necessary capabilities to address a problem or opportunity.

Example—Figure 2-7 shows how related causes and capabilities can be organized for the insurance company example.

2.4.5.3 Benchmarking

Another way to determine new capabilities is to conduct benchmarking studies of external organizations that solved similar problems or seized opportunities that the organization is considering. Benchmarking studies often guide final recommendations to address the situation as well as highlight which recommendations not to make. Stakeholders are almost certain to be interested in what the competition is doing, so it is always helpful to have answers about the competition when those questions arise. Benchmarking is also common in noncompetitive situations; for example, when one governmental agency or jurisdiction shares a solution approach with other groups.

A competitive analysis study typically falls into one of three types:

- Casual review of other organizations’ public documents such as corporate reports or web pages,

- Study of the major variables factoring into a solution or “secret shopping” at competitors’ stores or websites, or

- Reverse-engineering a specific product to determine its component details and the capabilities needed.

Benchmarking, like competitive analysis, provides insights into how other organizations are responding to the same challenges experienced by the performing organization. Benchmarking of capabilities provides insights that the organization would not have thought of on its own or would have used valuable time to discover them by trial and error.

Example—The insurance company could discover through benchmarking that a competitor offers video chat sessions between customers and their claims adjuster. This discovered capability should be scrutinized to determine the amount of value it would add to the potential solution under consideration.

2.4.6 Assess Current Capabilities of the Organization

Once it is known which capabilities are needed to correct a situation, it is necessary to determine the organization's current capabilities. The organization may have the necessary capabilities to resolve a situation without needing to add new ones. For example, an organization may already have the resources or capabilities needed to solve a problem through process improvement or staff reorganization. In those cases, the solutions tend to be simple, although not always easy to accomplish.

However, when a formal needs assessment is performed as described in this section, it is likely that the needed capabilities do not exist. Before recommending new capabilities, the business analyst should identify and assess current capabilities as they relate to the situation.

Common methods for assessing the current capability state include, but are not limited to the following:

- Process flows. Performing “as-is” process analysis or reviewing existing models reveals those current processes in place that could be refined or extended to fulfill the new capabilities. They also uncover resources that could potentially be redeployed to provide new capabilities. The absence of existing processes needed to solve a problem could reveal a larger disparity to fill.

- Enterprise and business architectures. Enterprise and business architectures are methods to describe an organization by mapping its essential characteristics such as people, locations, processes, applications, data, and technology. When a formal architectural framework is in place, it can be reviewed to provide a current capability inventory. As with any documentation, the architecture may not reflect reality and the current capability may well already be in place. Therefore when using existing documentation, effort needs to be made to validate that the models are up to date and still valid.

- Capability frameworks. A capability framework is a collection of an organization's capabilities, organized into manageable pieces, similar to business architecture. When this framework exists, it can be reviewed to provide a current capability baseline.

Example—An insurance company has current-state process flows for the claims processes such as the one shown in Figure 2-6. The company may also have some of the enterprise architecture in place, which may be useful even when models are at a high level. The process flows may need to be updated to reflect current processes, and the architecture components need to be revised to provide greater detail, but both serve as a starting point.

2.4.7 Identify Gaps in Organizational Capabilities

After identifying needed capabilities and assessing current capabilities related to a given situation, any gaps or missing capabilities that exist between the current and needed states are the capabilities that need to be added. These capabilities are commonly referred to as the “to be” features and functions and are easily identified by performing this gap analysis. Gap analysis is the technique of comparing the current state to the future state to identify the differences or gaps.

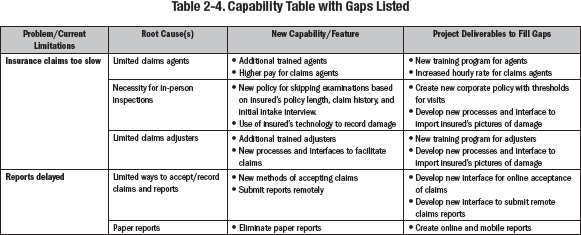

Example—In the insurance company example, at this stage of the needs assessment, the business analyst is analyzing the current capabilities to the list of needed capabilities in order to identify the capabilities that are missing to achieve the desired future state. The needed capabilities that are required to solve the business problem become the rationale for creating a program or project. Table 2-4 shows an updated capability table with the deliverables added that will fill the gaps.

2.5 Recommend Action to Address Business Needs

Once the gaps between the current and needed capabilities are identified, a recommendation can be made to fill the gaps. The needed features and functions are only part of the recommendation, though. The business analyst also provides a high-level approach to add the new capabilities, alternative approaches to consider, the feasibility of each alternative, and a preferred order to the alternatives. This work provides significant value to the organization as it helps to ensure that the organization does not implement the wrong solution.

2.5.1 Include a High-Level Approach for Adding Capabilities

A complete recommendation includes a high-level proposal stating how the needed capabilities will be acquired. This approach is not a detailed project management plan and does not include the level of detail in a project charter. Instead, it is a suggested path for adding the capabilities. The business analyst should solicit preliminary feedback from business and technical architects when the recommendation is going to include new or modified hardware or software. For complex situations, when developing the approach, the business analyst should work with the architects to develop a high-level view of how the new capabilities will be interfaced with existing systems and applications, noting any major dependencies that will exist when the new capabilities are added.

Example—Using the insurance company example, additional security infrastructure may be needed to allow claims to be submitted from mobile devices or to allow video chats with claims adjusters. Dependencies require time and money to implement before the desired capabilities can be added and will affect the net benefits of the chosen solution.

2.5.2 Provide Alternative Options for Satisfying the Business Need

There is rarely only one potential solution to a business problem. While there are often multiple approaches for adding new capabilities, a recommendation should include all of the most viable options. The standard build vs. buy alternatives are common options, and so are combinations of the two, in addition to alternative vendors to choose from. The business analyst evaluates and analyzes all the information gathered during the needs assessment to produce multiple possible solutions.

The primary reason for providing alternatives is to show that the alternatives were considered and to forestall objections from those who favor them. Another reason for including alternatives is because the preferred approach may not be acceptable. Constraints such as cost, schedule, staffing, or vendor bias may preclude an option from being chosen, therefore, potentially, one alternative will be an acceptable choice.

While the business analyst does not decide which solution may be the best one, the business analyst is usually expected to make a recommendation and to support the recommendation with facts and evidence. The solution decision is made primarily by the business sponsor or problem owner with additional input about solution feasibility from the solution team or those responsible for developing the solution.

2.5.3 Identify Constraints, Assumptions, and Risks for Each Option

Understanding the list of constraints, risks, and assumptions is useful when analyzing project proposals for addressing the business need and when conducting the project planning should the proposal be accepted.

Collaboration Point—Business analysts may draw on a project manager's expertise in risk planning and mitigation. Both roles are concerned with risk management. Project managers are focused on assessing the risks of the project as a whole, while the business analyst is focused on assessing the product risks. Business and technical architects can support this work too, as they may help uncover additional constraints or opportunities. Examples of this are the risks of a solution option or the risks associated with a particular portion of the business analysis process.

2.5.3.1 Constraints

Constraints are any limitations on a team's options to execute a program or project and may be business- or technical-related. It is important to assess any known constraints regarding a potential solution when generating alternatives. For example, if a time constraint to deliver a solution is imposed on a potential project, a custom-built solution may not be a viable option and would need to be removed or, at best, not be listed as a preferred option. Design and implementation constraints are important to investigate early in the process as well.

2.5.3.2 Assumptions

Assumptions are factors that are considered to be true, real, or certain, without actual proof or demonstration. Recommendations, proposals, and business cases are projections of the future, based on information limited to the person or team compiling them. As such, a number of assumptions are typically made, subject to the information available to the team. The major assumptions should be documented so that decision makers are aware of them when they evaluate the recommendations. If any assumptions are proven to be incorrect, it is important to reassess the identified needs or perhaps the entire business case.

2.5.3.3 Risks

Risks are uncertain events or conditions that may have a positive or negative effect on one or more project objectives if they occur. Potential risks for various alternatives can have a significant effect on the perception of business leaders when selecting potential projects. Major risks for each alternative should be noted along with potential mitigation strategies and their costs. Any risks that need a response may add cost to a potential solution.

2.5.4 Assess Feasibility and Organizational Impacts of Each Option

Before deciding which option is preferred, the business analyst assesses the feasibility of each potential option. In doing so, one or more options may be discarded due to their lack of feasibility. The assessment involves comparing potential solution options for how viable each appears to be on key variables or “feasibility factors” (explained below). This comparison along with the elimination of any options that are not deemed sufficiently feasible is called feasibility analysis.

Another reason for analyzing the feasibility of alternatives is to reserve the often painstaking work of cost-benefit analysis for only the most feasible option. The type of feasibility analysis described here is not a full business case in that the latter includes a complete economic analysis. Performing a complete business case only for the most viable options will save valuable time.

Typically, there is not just one factor, such as cost or time, that will determine whether an option is feasible or not. Feasibility is best analyzed according to a variety of important factors. Those factors and the questions to address are as follows:

2.5.4.1 Operational Feasibility

Operational feasibility represents how well the proposed solution fits the business need. It also encompasses the receptivity of the organization to the change and whether the change can be sustained after it is implemented. Meeting the business needs is the most important factor of all, because if an option does not solve the problem in question, the other factors are irrelevant. Sample questions to ask include:

- How well does the option in question meet the business needs?

- How does the solution fit into the organization, including its impact on the organization?

- How well do potential options meet the nonfunctional requirements, for example, sustainability, maintainability, supportability, and reliability?

2.5.4.2 Technology/System Feasibility

Technology feasibility pertains to whether or not the technology and technical skills exist or can be affordably obtained to adopt and support the proposed change. In addition, it includes whether the proposed change is compatible with other parts of the technical infrastructure. Questions to ask include:

- Does the technology for a potential solution exist in the organization?

- If not, is it feasible to acquire it?

- Does the organization have the technical expertise to install or operate the potential solution?

2.5.4.3 Cost-Effectiveness Feasibility

Before conducting a full-fledged cost-benefit analysis of a potential solution, a high-level assessment of the financial feasibility of potential solutions is essential. Cost-effectiveness during feasibility analysis is not intended to be a complete cost-benefit analysis, but an initial and high-level feasibility estimate of costs and value of the benefits. The full cost-benefit analysis is later performed on the most viable option(s) during business case preparation. Potential questions to ask include:

- What are the up-front and ongoing costs for the proposed solutions?

- Are the potential solutions affordable in view of the expected benefits?

- Can the funding be obtained for the investment needed?

2.5.4.4 Time Feasibility

A potential solution will be feasible if it can be delivered within time constraints. Potential questions to ask include:

- Can a given solution option be delivered to meet the organization's time frame?

- How reasonable is a proposed option's timetable?

- When a potential solution cannot be completely delivered by a certain deadline, is it acceptable to deliver it in stages and still meet business needs?

2.5.4.5 Assess Factors

The business analyst assesses the feasibility factors of each prospective solution option to determine how well these options contribute to the goals and objectives assessed earlier. In other words, the feasibility analysis uses the factors as criteria for judging how well each potential option solves the problem at hand and contributes to achieving the goals and objectives. Instead of working alone, it is important for the business analyst to also elicit, document, and leverage the judgments of affected stakeholders whenever possible.

Example—In the insurance company example, one of the needed capabilities is to use their policyholders’ technology to record damage. To add the capability, the company could install a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) package, develop the software in-house, or outsource the development. All three options may be viable and feasible choices.

2.5.5 Recommend the Most Viable Option

After examining potential options for addressing a business need, the business analyst needs to recommend the most viable option. Assuming that more than one option remains viable after feasibility analysis, the business analyst should recommend the most feasible option. If only one option is judged to be feasible, that option, in most cases, would be recommended. When there are no viable options to address the need, one option is to recommend that nothing be done.

When faced with two or more feasible options for solutions, the remaining choices can be rank-ordered based on how well each one meets the business need. For example, when an organization is reengineering its operations as opposed to outsourcing it, these two options can be ranked according to how well each one solves the business problems and contributes to business objectives.

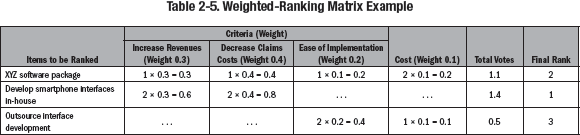

2.5.5.1 Weighted Ranking

Ranking two or more options can be done using various techniques. A practical and effective method is to use a weighted ranking matrix. A weighted ranking matrix or table combines pair-matching with weighted criteria to add objectivity to a recommendation. Pair-matching is performed by taking each option and comparing it one by one to all other options, and then voting or ranking which option is the most preferred. Weighted ranking is also useful to test an initial or intuitive choice against other options. The criteria used for ranking should align with the goals and objectives identified earlier in the needs assessment.

The basic approach is to select weighted criteria for each item to be ranked. Each option is ranked by voting on it against every other option, one at a time. Scores for each alternative are multiplied by the weights and added to arrive at the score for each option and the overall rankings. Guidelines for constructing and using a weighted ranking table are:

- Include between three and nine criteria as a practical range for the number of criteria. If a problem has fewer than three criteria, then a weighted ranking matrix is rarely needed to analyze each option. If there are more than nine criteria, it will be difficult for stakeholders to judge and compare the alternatives. Additionally, the problem may be overly complex and may need to be broken into subsets to properly analyze it.

- Assign weights by either percentages or decimals. It is usually preferable if the weights add up to 100% or 1.0. Stakeholders performing the ranking may prefer that each criterion have a weight between 1 and 100%.

- Determine how voting will be conducted. Voting for each compared pair of alternatives can be done with a simple “majority rules.” Another alternative is to record the number of stakeholders who vote for each pairing. This method provides one vote per person instead of one vote for the winner of the pairing. Teams may prefer to provide the stakeholders who have more authority in the organization with more votes. For example, a sponsor might receive two votes, and everyone else receives one vote.

- Check to ensure that the results make sense to the voters, since unrealistic results will not be helpful. Options that score excessively high or low could indicate skewed results or could indicate that one option is the clear favorite. Ask stakeholders for their subjective responses to the voting outcome. If the results are not trusted by the team, it usually means that the criteria, weights, or the voting method needs to be refined.

Example—One of the goals of the insurance company is to raise revenues. One criterion would be to compare alternatives against how well each option helps to increase revenue.

See Table 2-5 for an example of a weighted ranking matrix.

Collaboration Point—When constructing a weighted-ranking matrix, the business analyst should consult with the sponsor of the needs assessment to determine which stakeholders to include in the voting process. The stakeholders who are voting should be consulted about which criteria and weights to use. Likewise, decisions regarding the weighting system and the weights require collaboration with stakeholders.

2.5.6 Conduct Cost-Benefit Analysis for Recommended Option

Before recommending a preferred option, a cost-benefit analysis should be performed. The expected project benefits and costs need to be articulated in greater detail during a cost-benefit analysis than during a feasibility analysis. The earlier estimates performed during the feasibility analysis are now replaced by rough order-of-magnitude estimates of benefits and costs. If the business case is accepted and a project is initiated, these estimates will be used during project initiation.

Organizations often have standards that dictate when and how to perform a cost-benefit analysis, including which financial valuation methods to employ. Depending on the organization, consult with a financial analyst or a representative from finance to prepare the cost-benefit analysis to support the business case work. The most common valuation techniques are briefly described here and the recommendation should contain at least one of them.

2.5.6.1 Payback Period (PBP)

The payback period (PBP) is the time needed to recover a project investment, usually in months or years. The longer the PBP, the greater the risk. Some organizations set a threshold level that requires payback periods to be less than or equal to a certain period of time.

2.5.6.2 Return on Investment (ROI)

The return on investment (ROI) is the percentage return on an initial project investment. ROI is calculated by taking the projected average of all net benefits and dividing them by the initial project cost. This valuation method does not take into account ongoing costs of new products or services, but is still a widely used metric. Organizations often have “hurdle rates” that an expected ROI needs to exceed before a project is considered for selection.

2.5.6.3 Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

The internal rate of return (IRR) is the projected annual yield of a project investment, incorporating both initial and ongoing costs. IRR is the estimated growth rate percentage that a given project is expected to attain. Hurdle rates are often established, such as a projected IRR, and need to exceed a particular level in order for a project investment to be considered.

2.5.6.4 Net Present Value (NPV)

The net present value (NPV) is the future value of expected project benefits expressed in the value those benefits have at the time of investment. NPV takes into account current and future benefits, inflation, and it factors in the yield that could be obtained through investing in financial instruments as opposed to a project. Any NPV greater than zero is considered to be a worthwhile investment, although a project with an NPV less than zero may be approved if the initiative is a government mandate, for example.

The expected benefits listed in the cost-benefit analysis will be valuable measures to use when evaluating the outcomes of the program or project. During needs assessment, the business analyst may highlight key evaluation measures as part of the recommendation. If these measures are not captured during needs assessment, these are documented during business analysis planning, which is discussed in Section 3.

Collaboration Point—When estimating benefits and costs, a business analyst may work with a project manager with expertise in preparing estimates. Business analysts should also seek the support of financial analysts within the organization who can assist with the application of the valuation methods against the alternatives.

2.6 Assemble the Business Case

Not all business problems or opportunities require a formal business case. Executives in an organization may approve programs and projects based on competitive pressure, government mandate, or executive inclination. In those cases, a project charter to initiate a program or project is sufficient.

In most instances, the analysis performed in the business case helps organizations select the best programs and projects to meet the needs of the business. Business cases help organizations scrutinize programs and projects in a consistent manner. When this process is embraced, organizations will consistently make better decisions.

As described previously, a business case explores the nature of the problem or opportunity, determines its root causes or contributors to success, and presents many facets that contribute to a complete recommendation.

Organizations often have their own standards for what to include in a business case and will employ a set of templates or business case software to simplify and standardize the process. A common set of components in any business case should minimally include the following:

- Problem/Opportunity. Specify what is prompting the need for action. Use a situation statement or similar way to document the business problem or opportunity to be accrued through a program or project. Include relevant data to assess the situation and identify which stakeholders or stakeholder groups are affected.

- Analysis of the Situation. Organizational goals and objectives are listed to assess how a potential solution supports and contributes to them. Include root cause(s) of the problem or main contributors of an opportunity. Support the analysis through relevant data to confirm the rationale. Include needed capabilities versus existing capabilities. The gaps between them will form the program or project objectives.

- Recommendation. Present results of the feasibility analysis for each potential option. Specify any constraints, assumptions, risks, and dependencies for each option. Rank-order the alternatives and list the recommended one; include why it is recommended and why the others are not. Summarize the cost-benefit analysis for the recommended option. Include the implementation approach, including milestones, dependencies, roles, and responsibilities.

- Evaluation. Include a plan for measuring benefits realization. This plan typically includes the metrics to evaluate how the solution contributes to goals and objectives. It may necessitate additional work to capture and report those metrics.

Note: The formality of a documented business case and project charter is commonly required in large or highly regulated companies. While this formality may not always apply in smaller organizations or in some organizations which have adopted an agile approach, the thought process of defining the problem/opportunity, analyzing the situation, making recommendations, and defining evaluation criteria is applicable to all organizations.

2.6.1 Value of the Business Case

When a business case is created, it becomes a valued input to project initiation, providing the project team with a concise and comprehensive view of the business need and the approved solution to that need. More than a simple input, a business case is a living document that is constantly referenced throughout a program or project of work. It may be necessary to review and update a business case based on what is discovered as a program or project progresses over time.

When a business case is inadequate or nonexistent, the product scope may be unclear or poorly defined. This in turn often leads to scope creep, which results in rework, cost overruns, and project delays. A business case can help to address the possible risks of having to cancel a project due to loss of sponsor or stakeholder support, costs exceeding the perceived benefits, and changes to the business. Possibly worse than terminating a project is finishing a project only to have the end-product not be used because the solution did not match the business needs. The net effects of canceled projects and unused products are wasted investments, lost opportunity costs, and frustration.

Collaboration Point—Business analysts work closely with the sponsor to create a business case. When the project manager is known, the business analyst consults with the project manager to achieve a stronger business case through close collaboration. The project manager may better understand the business need, feasibility, risks, and other major facets of the business case. When a project or program is approved, the business analyst and project manager may work together during initiation to ensure the business case is properly translated into a project charter and/or similar document.