CHAPTER |

7 |

DYNAMIC EXPERIMENTATION

The natural world and the business world favor processes that allow different solutions to be tested with the advantageous ones being adopted (Ayala, 1978). Consider how the theory of evolution works. In the dynamic business world the ability to adapt is also critical for survival. Adaptation can be achieved through identifying options, and then exploring, testing, and changing in response to feedback (Highsmith, 2004). While experimenting with alternatives may involve duplication of effort, discovery of a better solution can lower overall cost (Highsmith, 2004). The key is to know what should be an experiment and what should be a deployment, and to manage them differently.

Structured Experimentation

Experimentation, discovery, and selection processes are helpful approaches for resolving unknowns in dynamic environments. Researchers, for example, cannot write a plan guaranteed to cure disease. Rather, they experiment, identify likely possibilities, and methodically eliminate dead-ends. The ability to select more promising ideas is enhanced by the elimination of others. Experiments confirm or eliminate an idea with feedback from the real world, allowing either customization or cancellation, thereby optimizing resourcing (Snowden & Boone, 2007). Sometimes, as in the case of Viagra, researchers start with a completely different objective, but keep in mind alternate applications (Kling, 1998). A portfolio of initiatives can test ideas and eliminate dead-ends like a production line for optimization. This is the process that underpins species survival, where natural selection provides continuous gene mutations, which are in effect experiments to allow adaption to a changing environment (De Meyer, Loch, & Pich, 2002). People with unsuccessful mutations die off, leaving the most successful ones.

In the case of project management, we are adapting to a changing business environment, and it is the idea that is killed off, not the team. In fact, the project team that tested the idea needs to share in the rewards for that achievement, as an incentive to continue conducting sensible experiments (De Meyer, Loch, & Pich, 2002). Controlled probing involves: sharing reward, clear limits in the form of an agreed deliverable (e.g., a feasibility report), a time limit, suitable stage gates with interactive controls such as review meetings (Jones, 2004), and finally the courage to kill dead-ends (Cooper, 2005).

Competing Experiments

NASA initiated competing experiments to more quickly develop the lunar module in the 1960s (Pich, Loch, & De Meyer 2002). When NASA was unsure of the final design for the lunar module itself, it initiated two competing endeavors for the lunar decent motor. After some experimentation it decided on the one that proved most appropriate for the final lunar module design. Car manufacturers develop a number of prototypes in parallel, choosing the ones that give the best market reaction (Sobek, Ward, & Liker, 1999). Kmart uses low-cost probes to monitor benefits and then chooses the one that is most promising (Cleland, 1999). Film directors shoot multiple endings, choosing the one that receives the best reaction from the test audience. Pfizer's disappointing heart medication, Viagra, turned into a success because the company took the time to investigate its side effects (Kling, 1998).

The prize concept is a way to attract competitors from many different backgrounds, to harness a variety different technologies and ideas, many of which the prize founder might never be able to harness through other means (Davila, Epstein, & Shelton, 2006). In 1919 French-born New York hotelier Raymond Orteig offered US$25,000 for the first person to fly non-stop across the Atlantic, subsequently won by Charles Lindbergh. The Orteig Prize was the inspiration for the X PRIZE, which led to the first privately financed spaceflight. The prize could just as easily be recognition, intellectual property (that can be commercialized), or even the award of a single source production contract for the winner (Rogerson, 1994).

The ubiquitous AK-47 assault rifle was actually designed through a process where teams were allowed to “mix and match features from different submissions, over a number of cycles, with more ideas available at each cycle” (McCarthy, 2010). While making the movie Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, director George Lucas discovered that one of the robot characters was malfunctioning. To mitigate the very high production costs of a delay, he commissioned competing teams on the other side of the world to develop a more reliable design and fly in for a demonstration competition before recommencing shooting only a few days later (Lucas, 1999). Parallelism is, however, most common in earlier stages of large-scale acquisitions, particularly in circumstances where the fixed costs involved in design are not large compared to mass production (Ergas & Menezes, 2004). When IBM discovered that it was falling behind in the microcomputer market, it launched two secret research teams that competed against each other (Lambert, 2009). The most successful approach was taken to fruition and changed the computer industry forever.

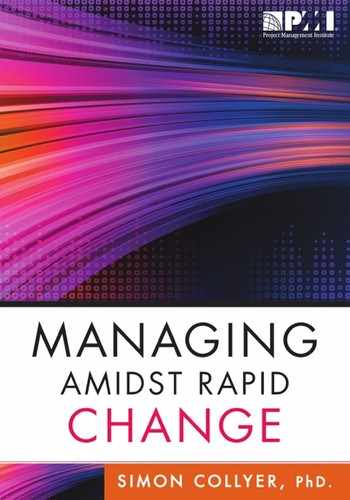

Figure 7.1 provides an illustration of the low-cost probes approach. A number of initiatives are started in parallel, with strict stage gates used to review progress and refocus limited resources to the most promising initiatives until the best solution is found.

While there can be additional cost to duplicate effort in parallel experiments, the approach offers a number of advantages in dynamic environments, including:

- Quality improvements: Where the correct approach is unclear, it can be used to discover the approach most likely to achieve the project's objectives.

- Time savings: In a dynamic environment, it is important to deliver value quickly, relevant to the environment before it significantly changes, so by testing approaches in parallel the project may be more likely to discover a solution before too much change or expenditure is incurred. It also allows direct comparison between mutually exclusive options.

- Cost savings: In a dynamic environment, parallel experiments help identify the most effective approach before too much money is committed. The other advantage can be in resource management, as a means to maximize resource usage by keeping the project pipeline full. For instance, in the words of a film producer in one of my studies, “If you have two or three things on, and one is pushed back to next year, you take another project and work out what you can do to accelerate it to this year.”

Case Study 11

Parallel Experiments – The Nuclear Bomb

During World War II, the allies were in a desperate race to build the nuclear bomb, racing against the Nazis, and to spare lives in the war with Japan. The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 people, costing billions of dollars. Because time was of the essence, the project explored three competing bomb types: uranium 235 (Hiroshima); plutonium (Nagasaki), and the “Super” (hydrogen bomb). The element plutonium had only been discovered in February 1941. Again to save time, three competing methods were employed to enrich the uranium, to separate the much more potent U-235 from its abundant relative, U-238. As construction crews poured the foundations for the largest roofed building in the world, it was still unclear what exactly was going to go inside the enrichment plant. In the end, all three enrichment methods were used in series.

Case Study 12

Compete – DARPA VTOL X-Plane Project

To design a new type of aircraft that can take off vertically yet fly much faster than a conventional helicopter, DARPA selected three companies to compete against each other. In the “VTOL X-Plane” project, different companies will work in parallel to develop different concept designs using their preferred technologies (e.g., tilt rotor, ducted fan, etc.). A single design will then be selected for construction of a demonstrator for test flights. The project is comprised of three phases scheduled over 52 months.

Case Study 13

The Kalashnikov Rifle – Compete and Share

The ubiquitous AK-47 assault rifle is infamous for being a more significant weapon of mass destruction than the nuclear bomb. The AK-47 was designed through a contest, which was a common management technique preferred by Stalin in the Soviet Union because it created a sense of urgency that resulted in rapid development. According to McCarthy (2010), “rival teams were given a set of specification and deadlines, and through a series of stages, the teams presented prototypes.” These prototypes were then tested and ranked in the field. Design convergence was an essential part of the process. The teams were then allowed to mix and match features from different submissions, with more ideas available to all of the teams at the start of each cycle without any restriction on Internet protocol (IP). At the end of the process, the very best features from each of the teams were incorporated. The weapon came about not through an individual epiphany or entrepreneurship but through state-led group design.

Fail as Quickly and Cheaply as Possible

Dynamic experimentation is all about testing options to identify solutions as quickly and as cheaply as possible. Clearly, this involves acceptance of failures. For instance, president of ALZA Corp. reported how the pharmaceutical industry required frequent experimentation and failure (Davila, Epstein, & Shelton, 2006). If you are going to have failures it helps to have them as quickly as possible with the lowest possible cost. Be clear about the uncertainties you are trying to resolve. Try to make the tests as cheap as possible. Use the results to inform new attempts, or the project plan.

Case Study 14

Google X Culture Supports Failure

Dominating and keeping pace at the same time can be difficult. IBM waited for the microcomputer market to take off before playing rapid catch up. Microsoft waited for the Internet to take off before embracing it. Google X is Google's DARPA, to future proof for a rapidly changing technology environment (Funnell, 2013b).

Google X is a secretive laboratory that is different than DARPA in that it isn't just focused on coming up with technology breakthroughs that enable industry. Google X is focused on commercially plausible projects that bring innovative ideas all the way to market. The Google founders wanted great scientists that were also able to “get stuff done” (Funnell, 2013b). The standard for success is whether the idea takes off in the real world. According to Teller (Funnell, 2013b): “If there's an enormous problem with the world, and we can convince ourselves that over some long but not unreasonable period of time we can make that problem go away, then we don't need a business plan.”

The founders of Google, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, looked at previous successes and failures in Silicon Valley, to build an environment that not only invents, but commercializes ideas in a way that helps the companies that sponsored the work. Early projects included the driverless car and Google Glass. Astro Teller, who manages Google X under Sergey Brin, says Google X is secretive because the workers have to be allowed to explore ideas in private without dead-ends being labeled as failures (Funnell, 2013b). To give an example of how far Google X goes to break down fears of failure, when Larry Page approved Google X's acquisition of a start-up that develops wind turbines mounted on an unmanned, fixed-wing aircraft tethered to the ground like kites, he reportedly told the team to “make sure to crash at least five of the devices in the near future” (Funnell, 2013b). The exploration of an idea is valued and celebrated. As a project is finished, whether it goes to production or fails to pan out, the researchers participate in a graduation ceremony, with diplomas and mortarboards emblazoned with the letter X. Interestingly in 2013, Google was still working out how to kill projects or amplify them at the right times.

Moonshot Projects

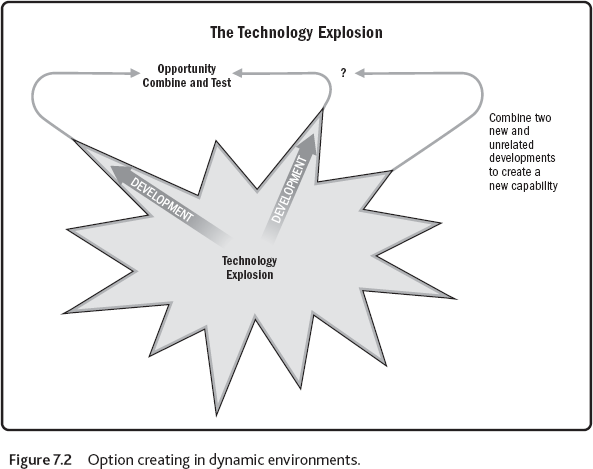

In dynamic environments, the rapid emergence of both opportunities and problems makes it ripe for harvesting with innovation projects. Innovation projects involve a cycle that requires: thinking (option creating); playing (evaluating and choosing); and doing (implementing) (Dodgson, Gann, & Salter, 2005). In many cases it's a matter of being aware of where developments are occurring, and thinking about where developments could be combined in some way relevant to your field of expertise, along the lines of Figure 7.2. A project can reduce complexity, increase speed, and yet innovate by simply combining two or more commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) products in a unique way.

Aspects of innovation can be leveraged in a project portfolio by using some of the following approaches (Acha, Gann, & Salter 2005):

- attaching small safe amounts of research work to existing robust projects;

- using high-profile innovation projects to attract talent;

- creating time off to build and integrate new capabilities (e.g., Google); and

- developing separate career structures to encourage capability development in both innovation management and technology.

Case Study 15

Creating the iPhone

Apple was doing well with the iPod when they started what would be a US$150 million project to build the iPhone. When conceiving the iPhone, Steve Jobs asked his engineers to try combining multi-touch display technology with a mobile phone, to remove the need for a physical keyboard and mouse. By 2005 Apple was selling 20 million phones a year.

Case Study 16

DARPA Project Selection

DARPA runs project-based assignments organized around a challenge model with actual results (not investigative). DARPA builds the following qualities into their projects (Greenwald 2013):

- Revolutionary, not incremental

- Goal-driven, with predefined, measurable milestones

- Collaborative and multidisciplinary

- Tolerant of risk, and failure

- Outsourced support personnel

They start projects with a set of questions known as Heilmeier Catechism (Brantley, 2012). These questions lay the groundwork for innovative projects by turning innovative ideas into pragmatic solutions. Heilmeier Catechism goes like this:

- What are you trying to do in plain English?

- How is it done today, and how is that limited?

- What's new in your approach and why do you think it will be successful?

- Who cares? If you're successful, what difference will it make?

- What are the risks and the payoffs?

- How much will it cost? How long will it take?

- How will you know if it's making progress

- How will you know it's a success?

Moonshot Portfolios

In a dynamic environment, parallel experimental projects allow direct comparison of alternative approaches. Each approach may be adequate for the task, but parallel experiments allow the most advantageous approach to be identified quickly and dead-ends removed before too much effort is expended. It can take courage to cancel endeavors before they are complete but this allows resources to be redirected in a way that maximizes overall productivity. This would suggest an organization with a reasonable project-cancellation rate may be healthier than one with no cancellations, or at least claims to have none. A venture capital project portfolio manager related an extreme example of this, saying, “venture capital comes with an understanding that there will be an acceptable failure and attrition rate; the flipside being that the less common successes are usually higher reward.” This means for dynamic environments there is a redefinition of what constitutes a project failure. When a project investigates the potential of a concept and rules it out, that is a success. If a project is canceled when the environment changes to make the original project objective irrevocably incompatible, the timely cancellation is a smart win, and is an important way to differentiate yourself from a competitor that may not have the same vigilance or courage. If a project fails to properly test an idea, or explore an opportunity, or is allowed to run too long or is not run for long enough; that can be a failure. A judgment on the likelihood and magnitude of the benefits needs to justify the efforts required to test and select. This is essentially the same principle applied to organizations that expend effort on bids for work. Experimentation should not be considered a “dirty word,” but rather it's the denial of experimentation or mismanagement of it that can cause problems in dynamic environments.

Practitioner Examples of Competing Experiments

Following are some examples of competing experiments reported by participants in my studies. A film director reported:

I've got at least five projects out and about in the market place, with different producers and different people, at different stages of consideration and it's exactly that multi-layered approach that's enabled me to survive. On average, for instance, a documentary maker estimated that one in twenty experiments turn out, and I would say, from my own experience, that that figure is accurate…in the film business it is an essential survival mechanism as the industry is both fickle and intensely competitive.

A film producer reported, “We have got at the moment about 21 film scripts in development, and we are aiming to make two or three a year.” A venture capitalist reported how they initiate multiple endeavors, accepting higher risk in the early stages, expecting that some will be “killed off,” and their resources redirected. Even a construction manager reported building several different experimental designs for an airport runway to see which would work best, allowing them to win the bid because they found a design that would save nine months on the schedule. A drug maker reported how scientific process taught them how unsuccessful experiments can teach as much as successful ones. A geothermal power generator related how they were collecting data through a series of ever-larger scale pilots, which were in effect independent experiments. Each successive version of the pilot justified itself independently based on revenue generated by that pilot, and if successfully justified a larger scale version (mining camp, village, town).