Appendix X3

CASE STUDY: BUILDING A CUSTOM BICYCLE

A project building a bicycle was selected to effectively contrast and demonstrate the many estimation practices used in portfolio, program, and project execution. For simplicity, material costs are excluded from this example.

SECTION 2—CONCEPTS

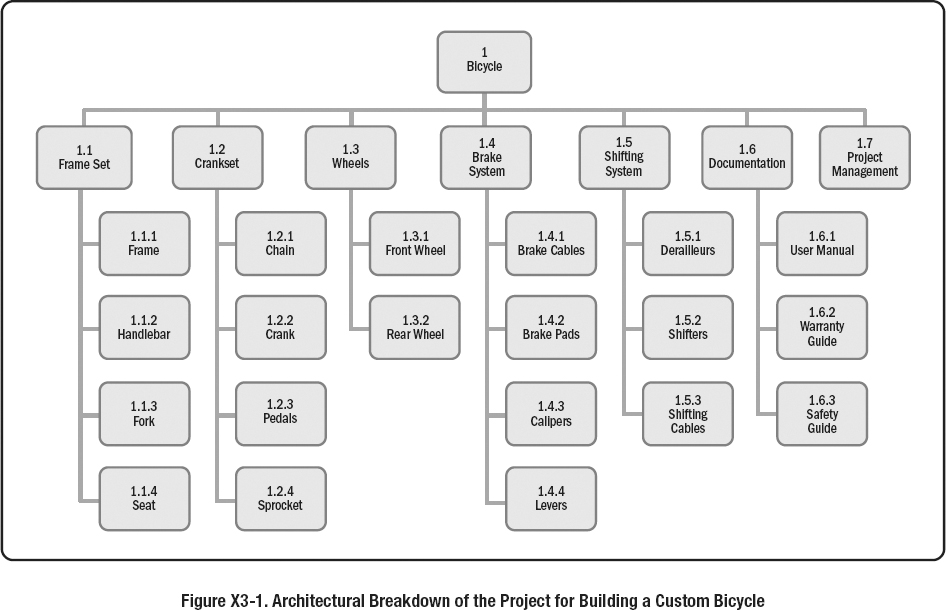

This case study is intended to exemplify estimation development during the project life cycle. It will illustrate iterative estimation, discussing the concepts presented in each section and accompanied by examples (see Figure X3-1). We use a bicycle as an example because it (a) is well understood by populations around the globe, (b) is a relatively simple mechanical model, and (c) has sufficient pieces and parts.

The ACME Bicycle Shop accepts the work to build an ultralight custom bicycle for a cyclist who has a competition in six months and intends to apply for a patent for some unique design features.

For this project, the technical team in the shop must define the design and build a prototype to be tested by the cyclist. Once the cyclist is happy with the prototype, the construction of her bicycle will start. The success criteria of this project are to get the final product delivered to the cyclist in plenty of time to test and tune the bicycle. The cyclist estimates they need to schedule at least two weeks for live road testing.

There are some assumptions and constraints to qualify for this competition:

◆The bicycle has specifications that limit the weight of the final product, requiring the use of ultralight materials to reach the maximum speed.

◆At the beginning of the project, it is not clear if the wheels will be manufactured in the store or if they will be purchased.

◆The cyclist has a prototype crankset that is still in the design phase.

◆The work team is not yet formed, but the owner has commitments from two expert colleagues who made special bikes for high-performance competitions a few years ago to come onto the team full-time. The owner knows that these experts will be glad to share their previous experience for estimating and building the new bicycle for the opportunity to work on a cutting-edge designed crankset.

SECTION 3—PREPARE TO ESTIMATE

The team is gathered to prepare the estimation of the special bicycle for the competition. Their goals are to:

◆Validate or, if not available, create a product-oriented WBS;

◆Define the estimating approach; and

◆Perform a resource gap analysis.

The owner of the store, who is the one who best understands the needs of the cyclist and documents the scope at a high level, has identified a list of activities to be carried out to build the bicycle, and has started an assumption log containing any assumptions and constraints on the project.

Since the project team has been given a WBS, the team asks the cyclist and store owner questions and decides on at least two estimating approaches to enhance the likelihood of developing reliable estimates. The constraints and assumptions are clear and listed in the log.

The project team consults with the stakeholders to gather information required for the Prepare to Estimate stage.

Most of the scope is easy to understand, but the crankset is still being engineered. Because the crankset is still in design, the scope isn't defined enough to estimate the materials and time to machine. The project team decides to split into three smaller teams: teams Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie. Teams Alpha and Bravo will apply different estimating techniques to the same work breakdowns, while team Charlie will use relative estimating techniques to remain adaptable to changes that may need to be made to the crankset.

One of the experts suggests using an analogous estimate, based on his own experience building several bicycles similar to this one a few years ago (minus the crankset). He will lead team Alpha. The second expert chose to contrast that with a bottom-up estimate by estimating component by component up front—she will lead team Bravo, using PERT estimation. Finally, team Charlie is left to work with the owner, machinist, and engineers to iteratively develop the crankset components and use relative estimation. The project team will use three methods to estimate within the project.

SECTION 4—CREATE ESTIMATES

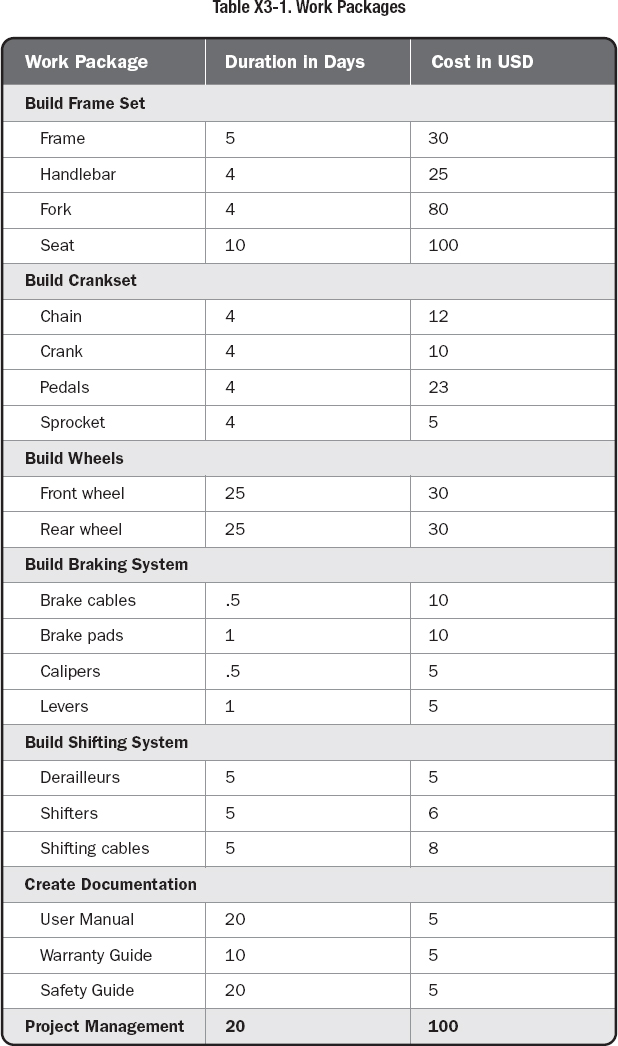

Team Alpha, led by the expert who has built custom models like this one, pulls the historical information on three of those projects for comparison. Comparing the data provided by the expert and normalizing where there are differences, team Alpha agrees on the work breakdown and estimates shown in Table X3-1. In addition, during the review of lessons learned on one of the projects selected for comparison, team Alpha realizes the quality of the braking system purchased commercially off the shelf is equal to the quality of the custom-engineered system originally required. With permission from the owner, they revise the estimates to use commercially procured braking systems and share the change with the entire team.

The project team uses the predetermined approach to Create Estimates for the project using information from similar projects and expert judgment.

Braking systems are available commercially of equal quality and would save the team 20 days for less than half the cost of machining them in-house. The 20 days are derived from the analogous estimate of previously completed work. For team Bravo, the bottom-up estimate needs the following inputs: the WBS shown above (see Table X3-1), the assumptions and constraints already known, and the estimating team.

The bottom-up technique actually starts at the highest level and decomposes, considering the bicycle as the deliverable to account for any changes that may have occurred from the WBS creation. Team Bravo uses a product-oriented WBS presenting a predictive life cycle. The decomposition made will produce the estimates at the component level, considering work package deliverables. The outcome is the predicted duration in days and the cost in U.S. dollars. This outcome is intended to be revisited during the life cycle of the project.

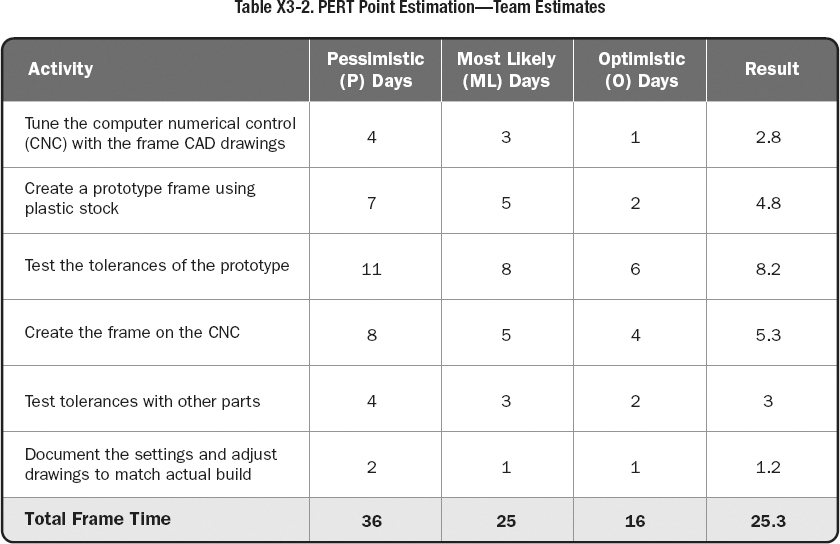

Starting with the frame set, the team decomposes the frame into work activities. The project manager decides to use the PERT formula for estimating and asks the team members to prepare three estimates. The first estimate is a best guess, which is the average amount of work the task might take if the team performed the task many times. The second estimate is the pessimistic estimate, which is the amount of work the task might take if the negative factors they identified on the risk log occurred. The third estimate is the optimistic estimate, which is the amount of work the task might take if the positive risks they identified do occur. The team creates three estimates for each work activity for the frame set as shown in Table X3-2.

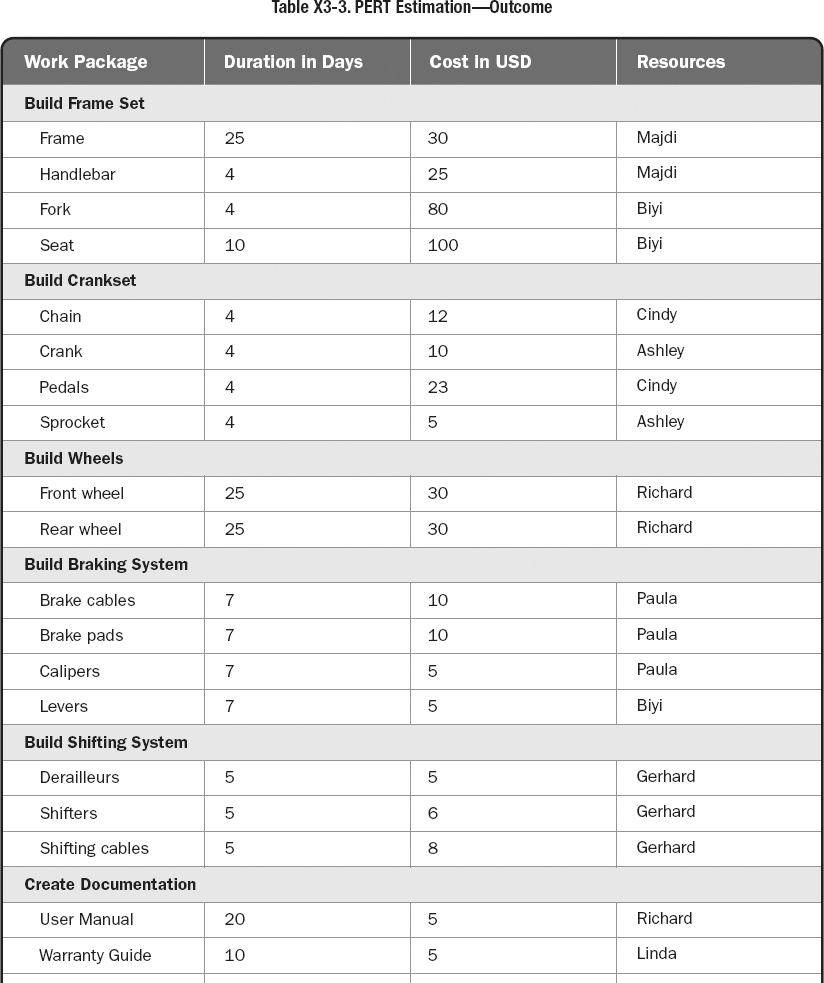

Lastly, the team applies a PERT formula (O+4ML+P)/6 to finalize the estimates for the frame set. Using this technique, the team continues estimating the entire WBS as shown in Table X3-3.

For team Charlie using an adaptive life cycle, the estimating process is completely different. The team is self-directed to deliver the crankset in time for testing the prototype. Starting from the original WBS, they decompose the crankset into user stories. Here a backlog is created from the WBS using a user story format, so the outcome and limitations are clear and embedded in the work. The user stories replace the documentation the other teams are estimating.

Team Charlie chooses to relatively size the backlog using a nonnumerical scale as an estimation method. From experience the team knows that machining a wheel is a medium-level effort compared to other work. The team selects T-shirt sizing as the relative measure (e.g., Small, Large, and X-Large). Walking through the backlog, the team compares each user story to the known work of a wheel and documents the relative size. The cyclist reminds team members that the minimum viable product of the project is a prototype for her to test.

The project team decomposes the WBS element crankset into user stories and prioritizes the backlog based on experience.

Note: The backlog of user stories must be prioritized before it is input into a schedule. Teams often prioritize the backlog immediately after sizing.

Team Charlie's backlog and estimate are shown in Table X3-4.

Team Charlie decides to build a prototype that can be tested on an existing custom bicycle and prioritizes the backlog according to priority of need to meet the minimum viable product: a prototype bicycle.

The cyclist will be part of the production team working on the design and testing the prototypes. She will provide feedback in order to evolve the prototype and clarify the acceptance criteria.

Teams Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie come together to share their preliminary estimates to develop a rough schedule. They adopt team Charlie's idea of using an existing custom bicycle to test the crankset.

Finally, since a wheel build was the baseline and its estimate was determined to be three days, the crankset was compared to that estimate and normalized to fit into the non-agile portions of the project.

The entire team adopts an agile practice of using information radiators or Kanban charts, and avoids the development of a Gantt chart. Using daily standups and practices to track the completed work in the information radiator as it is completed, the project manager can easily monitor progress and share important knowledge with the rest of the team. The team was given an order-of-magnitude estimate of US$500 for the total effort. Commercial part estimates were provided from a catalog.

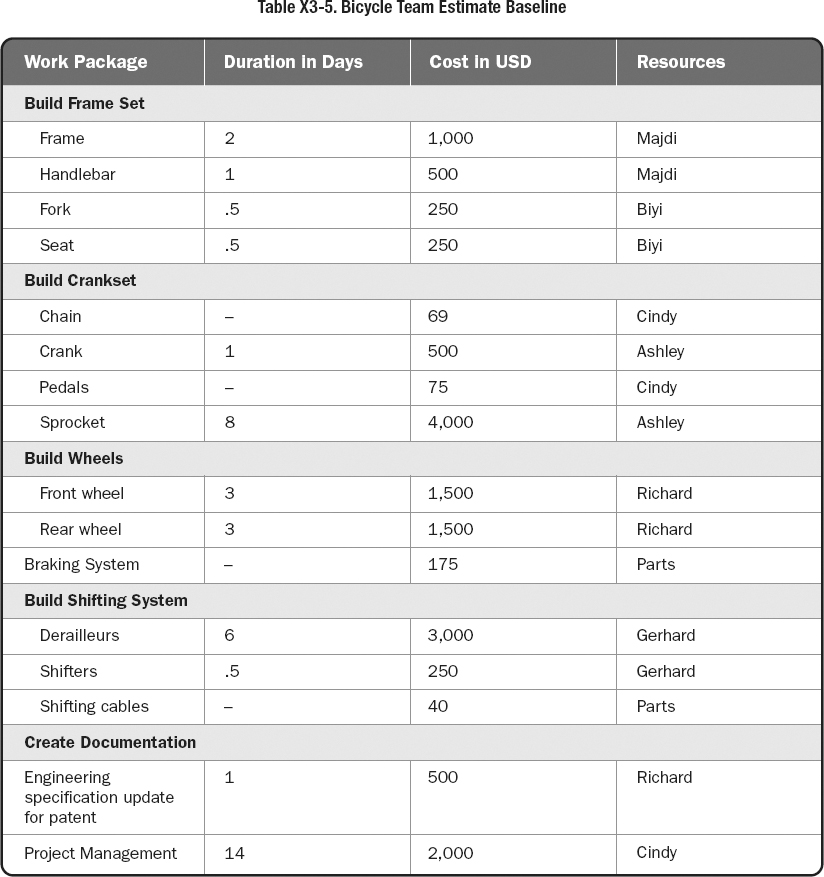

Working around schedules and parts lead times, the entire team consolidated the various estimates for each work package and created the overall project estimation baseline (see Table X3-4).

The estimates from teams Alpha and Bravo are very close in most areas, lending a high probability of accuracy in those estimates, except for the bicycle seat. Team Alpha's estimate was based on the materials currently available in the warehouse. Team Bravo's estimate was based on the specifications provided by the cyclist. The cyclist listened to the arguments and decided to stick with her specifications. The project manager updated the assumption log and project documents to reflect the cyclist's decision.

The final estimates are a combination of all the team estimates and are used to create a project baseline schedule (Table X3-5). New activities may be identified in any iteration.

SECTION 5—MANAGE ESTIMATES

Construction has started and the bicycle is in progress. The information radiators on the team's progress indicate progress according to plan and all parts have been received in the warehouse.

During the first month of work, the cyclist receives additional funding on condition of painting the sponsor's brand on the cyclist's outfit. This will allow acquiring a lighter frame set than the one already acquired. The prototype frame has already been built and the cyclist requires the change.

During a project review, the team comments on the new sponsor change and decides that a reestimate session will be performed to manage these changes. The revised estimation will constitute a new baseline including the approved change.

SECTION 6—IMPROVE ESTIMATING PROCESS

While building the custom cycle, the team conducted several retrospectives to determine if there were any lessons learned for process improvements as well as the root causes of estimation variances. The shop owner's decision to replace the planned custom frame with a commercially available frame decreased time from the schedule. The estimates were changed to also account for lead time to procure the parts as well as estimates for tasks associated with buying versus building.

Because the initial analogous estimates were so close to the three-point estimates, the shop owner realized that the analogous estimate was reliable, and additional efforts involved in three-point estimation did not provide additional confidence.

The team also enjoyed the fun of using T-shirts to size the effort but found them hard to integrate into the overall project estimate. However, the use of a relative item such as T-shirts saved a significant amount of time, which was applied to the task of physically building the bicycle. The team decided to continue the practice with the knowledge that a relative size was worth the challenges with creating an overall project estimate.