CHAPTER 14

Aligning with Teams

Organizations increase the chances of successfully implementing work-life supports when they consider teams in the process. As in all of the considerations for work-life supports, teams can be both a help and a hindrance to work-life supports. In fact, teamwork and collaboration are identified as one of the most important reasons for organizations to avoid allowing flexible working. While teamwork certainly isn’t a reason to avoid flexible working altogether, it is a factor to consider, plan around, and for which to find solutions. This chapter discusses the importance of teams and the ways that teams fulfill both task-oriented and relationship-oriented needs. It discusses the requirements for openness, trust, well-managed conflict, and strong inter-team relationships.

TASK AND RELATIONSHIP

For the first half of my career, I was significantly focused on team development and leadership development. Through that work, I was reminded frequently that the most effective teams pay attention to both task and relationship requirements. The considerations for flexible work within teams also follow this guideline. When teams are most successful, they nurture relationships and build trust. In addition, they pay attention to task, cultivate excellence, and members follow through with one another. Teams are critical to work-life supports because they are the context for meaningful work and for strong connections. Allen, a director of finance and administration, from a banking and finance organization, has a perspective on the importance of these team relationships:

What I learned long, long, ago is that one person can’t do it … you have to have a team. You have to empower that team … people don’t have to sit in a particular place in an org chart to be a leader, but they do have to get up out of their chairs and go and talk to people and help explain what we’re trying to do and to add value. The very concept of a team to me is that you have a diverse group of individuals to create an environment … where they get to grow and learn and be valuable. They can work anywhere, but you try to create a culture and an experience that they never want to leave. It’s about enabling people to be themselves, and yet be part of a team.

Lee, a senior vice president in charge of real estate and facilities from a technology company says, “We’re social creatures … and our most creative work occurs face to face … there’s nothing better than a hallway conversation to increase productivity.”

Recently, my team was conducting ethnographic studies (studies in which we observed workers in order to discover social dynamics in the work environment) at a well-known technology company in Silicon Valley. One of the dynamics we noticed was how powerful these hallway conversations were. In this particular company, the coffee bar was a magnet, a place where employees enjoyed snacks and drinks throughout the day. It was always a hive of activity and a place for cross-fertilization of ideas. During our study, every single conversation we observed started with a social connection (“How are your kids?” or “How was the ski weekend?”) and ended with a conversation that solved a problem or met a customer need. These are conversations that add tremendous value to an organization. The social relationships form the fabric of strong bonds and they create the networks through which customer needs are met and problems are solved.

Gallup published a book recently called Vital Friends,1 in which it shared its finding that the most important reason people stay with a company or a job is that they have at least one good friend with whom they work. Relationships help us thrive as individuals and as social creatures. They also help the organization thrive by retaining talent and getting good work done. In cases of remote work, technology can be used to bridge the gap. For workers who are always remote, connections through social networks, e-mail, or instant messaging can provide powerful connections. Virtual water coolers, as I mentioned previously, also help make connections as well. Some teams cannot ever choose to be face to face in real time. Their work is always virtual. In these cases, technology is a powerful enabler of teams and relationships.

OPENNESS AND TRUST

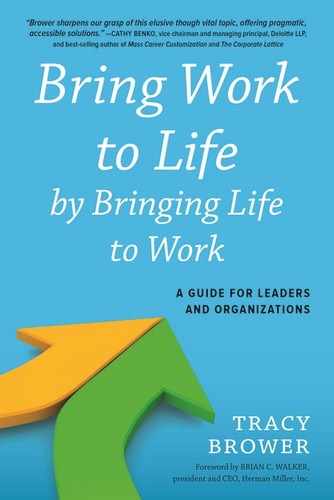

Openness and trust are among the factors in building a strong team that create abundance. The process of building trust is intricate and critically important to the overall health and performance of a team and the individuals on the team—and therefore to the successful provision of work-life supports. The Johari window, an exercise developed in 1955 by Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham, is a useful model. It suggests there are elements of ourselves known to us and others (open), as well as elements of ourselves known only to us. These are aspects of ourselves that we keep hidden. Aspects of ourselves that are known to others and not to ourselves are our blind spots.

Figure 14-1 Johari Window

The model suggests that we can reduce our blind spots by asking for feedback and being open to input from others. This is the lifeblood of healthy teams. With this greater self-awareness, the individuals and the team tend to become stronger.

My colleague Jolie describes “have-your-back” levels of trust. In this type of relationship team members “have each other’s backs,” meaning they provide one another with feedback and suggest areas for improvement. Sometimes the feedback is tough, but it is preferable for a team member to point out a problem so it can be solved before it is visible to the world outside the team. In have-your-back relationships, team members also advocate for one another, stand up for one another, and generally help one another accomplish goals.

In another portion of the Johari model, moving more aspects of ourselves into the “open” by sharing with the team can help build relationships. Teams tend to build these relationships bit by bit. A team member shares and then observes how a colleague handles the information and whether she responds in kind. As individuals share more openly, and as others respond positively in a trustworthy manner, a virtuous cycle of sharing and relationship building is established. The opposite is also true. When individuals share less, others tend to do the same. Earlier, I made the point that proximity is the number one determinant of relationships. The concept applies here too. When team members share openly, they foster closeness and emotional proximity, which builds relationships.

Knowing more about the people with whom we work builds relationships. I consulted with an oil and gas company a few years ago. Its exploration division was run by a high-powered, tough leader named Carlos. He was perceived as a work-above-all leader. One day, school was cancelled for his children due to a power outage at the school building. Carlos had no child care that day because his wife was out of town and they didn’t have backup child care. As a result, he took his children to work. They spent the day shadowing him, coloring on the whiteboard in his office, eating the candy out of the administrative assistant’s bowl, and generally making friends in the office. After that day, Carlos was appreciated differently by his team. For the first time, team members were able to see more sides of him—not only the dictatorial leader but the kind father and committed family man. The people with whom he worked learned more about him and had a more complete perspective on what made him tick. This is the Johari window in action.

The starting point for trust must be an overall personal philosophy of respecting others, suspending judgment, and assuming good intentions on the part of others. Approaching the world with this perspective tends to influence the way the individuals behave, which in turn influences the way others behave. Positive reinforcing cycles are established when people work together on tasks, communicate and share openly, provide recognition, are honest and keep promises (both personal and task-oriented promises), and support others.

AVOIDING ASSUMPTIONS

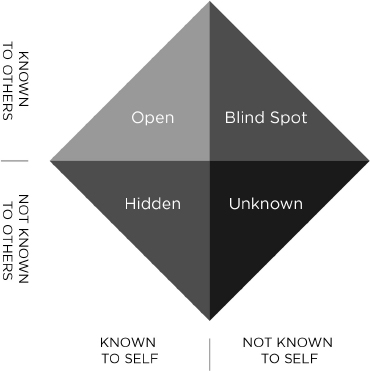

Another key way to think of teams and team member relationships is to consider the Ladder of Inference, which was first conceived by Chris Argyris. The Ladder of Inference begins with the concept that there is a pool of objective data that is observable and irrefutable. This pool is at the bottom of the ladder. As humans, we tend to quickly select data, add meaning to the data, make assumptions, draw conclusions, adopt overall beliefs, and take action based on those beliefs. We “climb a Ladder of Inference” through this process.

Problems arise when we come to vastly different conclusions regarding motives and make assumptions that are not based on the pool of data. For example, if a team member comes in late for work (the fact/observable data is that she was twenty minutes late for the meeting), another team member could quickly come to the conclusion that she was slacking off. A conflict could arise when the team member confronts her colleague about her frustrations with her slacking. The alternative is to “stay low on the Ladder of Inference,” asking more questions and focusing on the observable behaviors—in this case, the fact that the colleague was late for a meeting. By suspending judgment, assuming good intentions, and asking more questions, the colleague may discover that the team member was on a call that ran late with a customer. Conflict is averted and resolved more easily when team members avoid assumptions and focus more on facts and observable behaviors (staying low on the Ladder) and less on the conclusions they’ve drawn about others’ motives.

The relationship between the Johari window and the Ladder of Inference is this: people will interpret others’ actions through their own lens unless they know enough about others to guess at theirs. Carlos, whom I described earlier, is an example. Knowing more about his family and children provided a more nuanced lens through which others could view him. It is much easier to ascribe good intentions and bring accurate meaning when people know more about one other, and this allows them to interact at lower levels on the Ladder of Inference.

Figure 14-2 Ladder of Inference

In addition, when people make inferences and draw conclusions, they can be more accurate in the conclusions they draw because they know more about each other. Now, when the team member is tardy for the meeting, other team members might also know that she has been working on closing a tough deal with a customer in Abu Dhabi and consider that she may be late because of that. Or, on a personal note, if she is tardy for the meeting, team members can recall that her daughter has been struggling with a recent brain injury and even though she had to take her daughter to the doctor this morning, she was online late last night getting work done. At a minimum, these models suggest that asking questions of one another to learn more and assuming good intentions contribute significantly toward a positive team environment in which people feel free to bring all of themselves to work. People don’t trust what they don’t understand. Sharing, asking questions, and communicating openly increase understanding and contribute toward trust.

SUCCEEDING BY FAILING

In addition to building trust and avoiding assumptions, teams also create positive conditions by sharing challenges and learning from them together. I once worked in a team that was very broken. One of its features was that you could never let another team member “see you sweat.” Team members were in competition with each other for what they perceived to be scarce amounts of recognition and success. At meetings, team members would report on projects with a goal of presenting infallibility because they feared being perceived as weak or ineffective. They were regularly attempting to gain advantage over one another. In contrast, within my team today, we strive for the opposite type of culture. We share challenges and failures so we can learn from them, help each other, and boost each other up. When we share challenges and lessons learned, we provide feedback to one another, think together, and improve together.

A colleague said recently that she wants to have a team in which each person can “raise his hand and ask for help before things are a complete mess.” This type of open sharing builds trust. When team members work in alternative or flexible manners, it is even more important to have strong relationships so they can help one another through difficulties. When relationships are strong, they reduce stress and demands on employees, and they boost the perceived capacity a worker feels. If an employee needs help, the team is there. If she is stumbling, she can trust her teammates to help her. These are critical elements to the success of work-life supports and to bringing work to life.

CONFLICT

Teams always face conflict. A healthy team is not characterized by an absence of conflict, but rather by well-managed conflict. Introducing work-life support options can stretch a team and its members in new ways. Some work-life supports change the typical ways of working and can therefore be the sources of dissonance or conflict. There is a proverb that says, “A boat that isn’t going anywhere doesn’t make any waves.” A related proverb says, “When two heads think the same way, one is unnecessary.” Conflict is necessary and helpful to progress, but when it isn’t managed well, it can be very damaging.

Many years ago, our company utilized a personality profile for sales personnel in order to develop skills and drive performance. The expectation was that if employees better understood their personalities, they would be better team members and leaders. One of the indicators was the extent to which an individual created conflict. There were “grenade throwers” who would regularly initiate conflict. It was surprising to some that this was considered a significantly positive trait, correlated with team and leadership success. The catch? The “grenade throwing” employee had to have already created a safe, trusting dynamic within the team. When people on the team felt valued and safe, they were able to better work through disagreements and conflict with a learning perspective, building toward a common goal.

The majority of people are not very comfortable with conflict. They either lack the confidence or skills to work through conflict. However, conflict itself is not negative or damaging to a team. Conflict badly managed, or unmanaged, is damaging. In fact, conflict is a cue regarding passion since it only exists when workers care enough to feel passionately or disagree. In addition, every conflict situation features an ROI (return on investment) assessment. A person asks herself, consciously or not, whether the investment of energy in the conflict is worthwhile.

Teams that afford the opportunity for work-life supports may experience more conflict toward the beginning of the journey to establish work flexibility, as it is part of the process of adapting to change. It is helpful to start with a trusting team environment and to deal with issues as they occur. A friend in Texas says, “You need to lay the skunk on the table.” In addition to getting issues out in the open, dealing with them face to face and staying low on the Ladder of Inference are a boon for solving problems quickly and growing from conflict situations.

Well-managed conflict asks tough questions and invites disagreement with the expectation that it will catalyze informed, effective decision making. Introducing dissonance—tension between where we are and where we’d rather be—interrupts the status quo and helps individuals and teams move forward. Deciding which work-life supports to enact for an organization can be controversial and have broad implications across the company and its employees. Well-managed debate and conflict produce the best decisions.

A COMMON ENEMY

Another way to manage conflict is through the classic sociological concept of the “common enemy phenomenon.” This dynamic was (supposedly) discovered during a sociologist’s Boy Scout expedition. During the trip, the scouts were having a difficult time getting along. There were some strong personalities in the group and they were arguing about everything from how many marshmallows to roast to how to set up the tent. On their first night in the woods, a terrible storm developed. The campers were suddenly forced to work together to secure tents, put supplies under dry wraps, and stay warm all night through the howling storm. The storm bonded the campers together against a common enemy. A similar phenomenon has occurred in cases where New Yorkers have been trapped in elevators. Twice in recent memory, New York City has sustained a fairly significant power outage in which people throughout the city have been stuck together in elevators. Those interviewed about the experience report having bonded with the others with whom they were trapped. Sometimes these bonds last many years.

A leader can create this same phenomenon for a team. Common enemies become mutual challenges. By clarifying the group’s common goals and by pointing out shared obstacles—common enemies such as storms or power outages or figuring out how to stay connected when some team members work at home—the leader can create a situation in which members collaborate and connect in order to make new ways of working effective for the team. While it is counter-productive to identify another team within the organization as a common enemy, it is quite effective to identify situations as common challenges. For example, the need to learn a new technological platform or the need to respond to a unique customer requirement can be positive, mutual challenges around which a team can rally. The goal is to unite the team in a positive, mutual pursuit. Our team uses a “Team Playbook” as a vehicle to codify and continuously update the things that unite us. In it, we document our vision, purpose, and operating processes. We also document our interaction norms. These interaction norms, which we create collaboratively, identify how we work together and the protocols regarding how we will treat one another. Sharing openly, assuming good intentions, disagreeing constructively, and learning from one another are at the top of the list.

TEAM COMMITMENTS TO WORK-LIFE SUPPORTS

When team members are working together to accommodate work-life supports, they are well served to establish a mutual commitment among the employee, the work team leader, and the team itself. These, too, fit within a “Team Playbook.” Companies that take this approach generally have a brief agreement that defines how often the employee will work away from the office and the schedule for this working time. The agreements also typically define the ways in which the employee and the team will stay in touch through meetings, phone calls, instant messaging, or the like. These agreements set explicit guidelines for the type of equipment the employee will have in order to stay connected.

For example, an employee sometimes has to commit to having reliable internet connectivity, a printer, or Skype. Sometimes these are company-provided and other times the employee is expected to provide them at his own expense in exchange for the privilege of working away from the office. In cases where an employee is working at home and has young children, these agreements often make an explicit reference to child care. For example, “The employee has appropriate child care, and working at home is not being used as a substitute for child care.” While it is a rare employee who will use working at home as a substitute for child care, concern does exist and an explicit guideline to this end is helpful in putting minds at ease.

Guidelines typically also include formal checkpoints. Often, these are quarterly or biannual opportunities to formally review how the process is working and whether any alterations are necessary. Some of the most progressive companies expect that entire teams will sign a commitment. In cases of these agreements, all the team members commit to helping an individual employee succeed in alternative working and commit to certain protocols for communication. The advantage of this type of process and the transparency it fosters is that the whole team shares in a common goal and works toward mutual success. This reinforcement of shared objectives tends to increase the odds of success for the working model, for both the individual and the team as a whole.

INTER-TEAM RELATIONSHIPS

So far I’ve been focusing on intra-team relationships—relationships within the team. Inter-team relationships are those that form between teams. Like the trust that builds within teams, individuals and organizations are also served by trust and learning that occurs between and among teams. For example, the Johari window is relevant for teams as well as for individuals. A team can have information about itself that it shares openly with the world and also have blind spots in which it must seek feedback from the system in order to be more effective. As teams navigate work-life supports and as they learn what works and what doesn’t, they are well served to communicate with other teams within the organization. One organization with which I consult accomplishes this cross-team interaction through quarterly “share outs,” in which a few teams explain their recent projects, lessons learned, and challenges. Other teams leverage technology platforms such as SharePoint or a chatter feed on a sales management platform, on which they post questions or issues, help one another, and learn together.

IN SUM

Healthy teams that work well together and provide a positive overall experience for employees are themselves a support for team members who are navigating work and life demands. Teams are one of the most powerful work-life supports because they provide employees with fulfillment through connections and meaningful tasks shared with others. Trust and openness, well-managed conflict, and clear expectations for working together are context for strong task performance and strong relationships. Organizations create abundance and bring work to life through the strength of teams.