What Is Social Media Marketing?

Take everything you like seriously, except yourselves

In the rather contradictory manner of other aspects of this book, I’m going to start a chapter titled what is social media marketing with a section detailing what social media marketing is not when it is not social media marketing. Furthermore, the second section of the chapter considers when social media marketing is social media marketing. Confused? Hopefully not by the time you have finished the chapter.

3.1 What Is Social Media Marketing Not?

I would suggest that the following points are at the core of the Emperor’s New Digital Clothes and so the not issue is important. Here’s what it is not.

1. Social media marketing is not a magic bullet for all the woes of every organization, brand and, product. Or put another way—if is not too cheap a reference to the book’s title—it is not the panacea to all the business and marketing problems, ailments, and issues for every organization, brand, and product known to mankind.

2. Social media marketing is not free. This issue pervades all subsequent chapters of this book. To paraphrase Mark Twain; reports that social media marketing is free are greatly exaggerated. Just to make myself clear—social media marketing is not, nor ever was, free. This deeply flawed proposition originated, presumably, from the fact that setting up a Facebook page or a blog (on the likes of Blogger.com) incurs no charge. And if the social media content you develop and publish is personal (i.e., not commercial), then it costs you only your free time. However, if that Facebook page or blog is commercial, that is; it is part of the marketing for an organization, brand, person, entity, or product—then the development time is chargeable. If nothing else, there is the opportunity cost of doing something else in the time spent developing the social media content.

3. Social media marketing is not advertising on social media platforms. Advertising on social media platforms is advertising. Conversely, if you have a Facebook page, that is not advertising. It is social media marketing. The objectives, required skills, management—indeed, everything else covered in subsequent chapters of this book—for effective social media marketing are very different to those required for effective online advertising. Consider also that the same ad can appear elsewhere online, search engine results pages (SERPs) for example. I find it extremely frustrating that folk talking or writing about social media marketing include advertising on platforms such as Facebook or Twitter as part of the discipline. We don’t call advertising on TV, TV marketing, we call it TV advertising. We don’t call advertising on radio, radio marketing, we call it radio advertising. We don’t call advertising in out-of-home formats, out-ofhome marketing, we call it out-of-home advertising (OOHA). So why do we call advertising on social media platforms social media marketing? I think there are two key reasons, though the second may be a result of the first. As I cover in more detail in Chapter 5 (Section 5.1), a great many of the people working in all aspects of digital marketing are not marketers. That is, they have no marketing experience or education. Often from technical backgrounds, they have mastered an element of digital marketing (search engine optimization or programmatic advertising, for example) but they do not know how it fits in with other aspects of digital marketing or understand how that aspect of digital marketing fits in with strategic marketing objectives. Hence, we have people working in social media marketing who do not appreciate that there is a difference between advertising and marketing. The second reason is that marketers—and people who write books about marketing—like to have things in nice clean categories because they make for convenient departments or chapters. Ergo, anything with any connection to social media is social media marketing. I prefer to categorize by disciplines so, in my digital marketing books, online advertising covers advertising on all of the different platforms that accommodate it, including websites, search engine results pages, and social media pages. Essentially they are all an aspect of programmatic network advertising—and that is not a subject that has any place in a book on social media marketing. A caveat to this is that on Facebook (and coming soon on all other platforms?) marketers can pay to boost a post. Some call this advertising; I would call it a promotion (in marketing terms, advertising is part of the promotional mix) if only so it does not get mixed up with advertising on Facebook. If you can have a caveat to a caveat, here is one. Some folk call the practice of boosting posts paid social; and some call advertising on social media paid social. And some call any social media practice that involves payment of a fee paid social. We do seem to weave an unnecessarily tangled web at times. Another issue with regard to advertising on social media platforms is the common failing for marketers, researchers, writers, and commentators to differentiate between social media marketing and advertising on social media. I frequently come across managers who say they conduct social media marketing, only to discover they advertise on social media. We also need to consider the methodology of some research and how it defines social media marketing. A statistic that reads (something like) “more videos are shown on social media than other online platforms” for example, takes on a different context if video ads are included or excluded.

A final point on the subject that has relevance to the Emperor’s New Digital Clothes syndrome is how it too—like social media marketing itself—tends to fall victim to overhyping. Social media advocates (can I interest you in a new set of clothes sir?) would have us believe that social is the home of both video in general and the video ad. In the UK at least this is not the case—I suspect these statistics are not so different to what they might be for the United States.

According to research from Thinkbox,1 the marketing body for commercial TV in the UK, TV accounted for 74.8 percent of all videos viewed and a whopping 93.8 percent of video ads viewed in the UK in 2016 (note that these could be watched either live, playback, or on a broadcaster’s video on demand service) so despite all the talk of how digital is taking over the marketing world, perhaps the old style of clothes that consumers can actually see are still the best option for that ever-diminishing marketing budget?

3.2 When Is Social Media Marketing Not Social Media Marketing?

It is, perhaps, a reflection of the popularity—or whisper it quietly—the spread of the Emperor’s New Digital Clothes, that social media marketing is given credit for any and all marketing campaigns that have any connection or association with social media. For example, the streaming of live events to be watched on mobile devices is generally attributed as being to social media marketing. The reason for this is that the platforms used for such events are often YouTube or Facebook Live, both of which are stalwarts of social media. I am—if somewhat reluctantly—willing to accept this as social media marketing, and so it is included at the end of this chapter. My caveat, however, is that the broadcast must be hosted on a third-party social media platform. For example; when, in November 2016, denim apparel manufacturer Wrangler teamed up with George Strait in showing a live stream of the country music icon’s return to the stage for the first time in 34 years, it is not surprising that it was promoted as being social media marketing. After all, it was live streaming of an event. It was produced to be watched on mobile devices. Sounds like social media marketing doesn’t it? But the broadcast was hosted on Wrangler’s own media hub (a website, wranglernetwork.com), not on a third-party platform. Therefore, although it may be considered to be digital marketing, is it social media marketing? In traditional marketing terms: is it simply sponsorship? However, closer inspection of the details suggests that the event was part of an agreement between Wrangler and Universal Music Group Nashville whereby the former has exclusive rights to broadcast content from the latter. Now that sounds more like a strategic business deal than social media marketing.

Further examples of faux social media marketing from the latter months of 2016 include:

• IHOP restaurants’ photo contest to win a year’s worth of breakfast as part of its Eat Up Every Moment campaign. Photo contests have been a staple of marketing since photography was invented. That Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram were used to enter a picture into the competition makes social media the mode of entry to a competition, not the type of marketing.

• To launch new mint and strawberry cheesecake flavors, Oreo used a social influencer—with over four million views on Facebook—to promote the launch. This was old-school promotion using a celebrity endorsement, not a new concept in marketing made possible only by the invention of online social media.

• Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey USA Barrel Hunt contest was an old-fashioned scavenger hunt—but one where the clues were posted on its Facebook page rather than any other form of publication.

• In December 2016, ABC announced that fans of “The Bachelor” would have another way to keep in touch with the happenings thanks to the introduction of a new Snapchat companion show called “Watch Party.” My take on this is that “Watch Party” is a TV program broadcast on a social media platform. It is not social media marketing—though I do appreciate that the Snapchat show might encourage other social media engagement.

• In late December (the 29th, it couldn’t have been much later) 2016, the National Football League announced that it would be streaming games on China’s premier social media network Sina Weibo. That is a live broadcast, not social media marketing.

As with many aspects of the subject, the association to social media of these strategies and campaigns is promoted by social media marketing departments and agencies as being part of their remit. Given that budgets depend on such things it is hard to blame them, but that is rather harsh on all the other marketing folk who would have been involved in—for example—the development and marketing (packaging, TV advertising, in-store promotion) for the new Oreo flavors mentioned previously.

The final this is not social media marketing goes under the rather sinister name of dark social. The term confuses some as it is associated with the dark web—something that really does have sinister overtones as it often linked to illegal or dubious activities. Dark social, on the other hand, is the description given to social messages sent directly to the recipient (normally by either e-mail, the personal massage facility on a social media platform, or a messaging app) that are not placed in a public space such as Facebook. That only the addressee sees the message has resulted in these e-mails and personal or app messages being dubbed dark social—as in: not visible to everyone. The association with social comes from the dark messages being in response to a communication on social media. For example a question posed in a public forum is answered by e-mail or personal message. There are two aspects to this for the organization to consider, depending on who is the recipient of the dark social message.

1. The dark message is sent by consumers to other consumers via e-mail or personal message; for example, “the product on this Facebook page is great/rubbish, buy it/don’t buy it.” In this scenario the social media marketers have lost track of the conversation. The conversation is out in the wind. In marketing terms it is word-of-mouth, a subject mentioned in the next section of this chapter.

2. The dark message is sent via e-mail or personal message by the consumers to the marketer. For example, “could you tell me if the product on this Facebook page is available in my city?” or “I have a problem with your product, can you help?” However, it is important to note that such a message should not be considered to be social media marketing as the contact is between an individual and the organization in a private conversation, not one conducted in the public arena of a social media platform. In just the same way as it would in the real world, when communication switches from public to private, not only does the whole tone and nature of that conversation change, but different skills to those practiced on social media are required to address the consumer’s personal query. In these two examples, the problem should be handled by the after-sales service team and the product availability question by the sales team. In the sales scenario, I would suggest that social media has served as a lead generator, with the social media content prompting the consumer to contact the organization.

However, this transfer of the consumer from one element of marketing (social media) to another (sales or service and support) is where problems frequently exist. There should be no difficulty in applying this kind of joined-up thinking, but sadly, the joined-up organization rarely exists. The problem? Twenty years in and digital is still too often seen as a separate entity to other aspects of marketing. One of the biggest problems I come across in larger organizations, particularly B2B, is the disconnection between the web presence and the sales team.

A key problem of dark social is, therefore, that the social team has to justify its existence and budget, so want to hold onto contacts made on a social media platform when realistically their job has been done in initiating the contact. If what constitutes dark social (i.e., personal contact) is kept within the social media remit then the customer slips off the digital radar. Take, for example, a social media-originated message that is copied or attached to an e-mail—there is no digital record (footprint) of that message being disseminated beyond its original publication. This is unlike, for example, a click on a link on social media to the brand website. It is worth a quick reminder here that—perhaps for the aforementioned social media marketers who know little outside their domain—e-mail is still the most used platform on the Internet. Indeed, Gmail alone is used more than all social media put together. In comparison, social media is very much the new kid on the block making a lot of noise to be noticed. Note: see title of this book.

However, it only gets worse for marketers in that e-mail is not the only element of dark social in that messaging apps on the likes of WhatsApp, WeChat, and Facebook Messenger are all one-to-one forms of digital communication. Note also that Facebook and Linkedin offer “unpublished posts,” which are promoted and targeted posts that are not published on the brand page—these are also sometimes described as being part of dark social.

A postscript to this would be that social media marketing is generally recognized as being a method of encouraging engagement by the customer with the organization, brand, or product that is conducted in a public environment. If that same objective is sought via direct communication with individuals it has existed as the concept of relationship marketing for quite some time. However, some of us sales and marketing old timers consider that relationship marketing is little more than what we used to call good customer service. Again, specialist digital marketers take note.

3.3 Models Associated With Social Media Marketing

Having addressed the issue of what isn’t social media marketing, there are a number of concepts that are very closely associated with social media marketing, but are not part of social media marketing as such. However, it is important that these models are understood before any attempt at social media marketing is considered.

3.3.1 Viral Marketing

Prior to the Internet and social media, viral marketing was known as word-of-mouth marketing. However, as seems the case in so many aspects of digital marketing, a word of explanation is required before the subject is investigated any further. Word-of-mouth is: “an oral, person-toperson communication between a receiver and a communicator (whom the receiver perceives as a non-commercial) regarding a brand, a product or a service” (Arndt 1967). In other words, it is customers passing on their opinion about a product, brand, or organization because they are impressed by it. That these discussions often took place in its vicinity, this was often called water cooler talk—who hasn’t recommended a movie or retail outlet in such circumstances? And how many people heard of the Atkin’s Diet in this way—a product that lent itself to self-propagation if ever there was one. With the advent of the Internet the water cooler became merely a place to get a drink, e-mail and then social media taking its place. No longer did movie goers tell a couple of people their views on a movie, they could tell dozens, hundreds, even thousands at the click of a mouse or touch of a screen. A final point on the issue of the digital viral story is that those that have gone most viral (I hate to think what my old English teacher at grammar school would have to say about how I now use the word viral) have had a nonviral boost from a broadcast media. There is nothing like a humorous cell phone video of a man chasing his dog through a park shouting its name to end a news bulletin2 and that will reach a whole new audience who will in turn reach for their mobile device and immediately look it up (research suggests most people watch TV and look at another screen at the same time). A mention in a newspaper has just the same effect.

Word-of-mouth marketing, on the other hand, involves the marketer putting out a marketing message and then encouraging—or persuading—people to pass that message on to other people, preferably who will be potential customers for the product, brand, or organization. Importantly, customers might be offered an inducement to spread the word. For example: free or discounted products if friends are introduced to a product that they subsequently purchase—Uber has used this tactic extensively. Indeed, using the taxi company as an example: if a colleague told you that they had used Uber and they were impressed with the service, that would be word-of-mouth. If that colleague forwarded Uber’s pre-formed text to you and you got a $10 discount on your first journey, that would be word-of-mouth marketing.

Furthermore, there is the issue of the term viral in this context. Viral and viruses in nature have existed, well… forever. In the digital age, however, the terms have become associated with something—usually malevolent—that spreads quickly and easily from one computer to another. It was inevitable, therefore, that when digital technology (predominantly by way of e-mail) enabled people to send the same message to tens/hundreds/thousands of their friends and associates with the click of a mouse that it became known as the message going viral. These viral messages were usually entertaining in some way, hence the legend of the cute cat and skateboarding dog. Jokes too got around at alarming speed. Not social media as such, but closely related, is that in the early days of e-mail I spent a lot of time advising organizations on a staff protocol for sending and receiving e-mails on the company domain name e-mail server. One of the serious issues was staff receiving viral jokes that were of a sexual, racial, or otherwise offensive nature—which then frequently found their way into the in-boxes of other staff who were rightly offended. Does that sound familiar to organization’s social media protocols being developed now? Or perhaps more relevantly; those social media protocols that should be, but are not being, developed.

Viral marketing, described as “network-enhanced word-of-mouth” by the venture capitalist behind Hotmail, Steve Jurvetson—who is commonly attributed with being the first to use the term—is the practice of marketers deliberately developing a marketing message that will go digitally viral around potential customers. That marketers hoped that the message, whatever it might be, would create a buzz among the public resulted in the procedure also being known as buzz marketing. In keeping with other aspects of social media marketing covered in this book, however, given the nature of the message in many viral campaigns, perhaps viral advertising better suits the practice.

It is also impossible to emphasize enough that, to be successful, viral marketing campaigns must be strategically planned and executed, they do not just happen. Furthermore, many campaigns that are strategically planned and executed fail to go viral—we only hear of the ones that do.

However, I would contest that pure marketing viral is a fiction. In the UK, upon winning a top business award, Sarah Wood, founder of tech firm Unruly, was asked in a BBC radio interview: “what does Unruly do?” and she replied: “We help videos go viral.” Yes, for the uninitiated, commercial virals don’t just happen—though cute cats and skateboarding dogs might. There was even a live video feed of a puddle in a city near me last year that, it seems, was watched by most people in the known universe. Maybe back in 2007 Ms Wood read an excellent article in Techcrunch.com and was inspired to set up her business. I’ve been pointing skeptical students at it for the last 10 years. It is called The Secret Strategies Behind Many Viral Videos. Just put that into a search engine and have a read. If you are not aware of this stuff it is a real eye-opener.

I trust that by now it is obvious that the contemporary viral marketing campaign depends on social media to succeed—hence its inclusion in this chapter.

3.3.2 Influencers

In any society there has always existed (and always will exist) a very small number of people who will be advocates—evangelists even—of any product, brand, or organization. These folk wield a significant influence over the buying decisions of people who seek advice, guidance, or recommendation on particular products, brands, or organizations. Those from whom such advice is sought are identified by marketers as being influencers.

In the previous chapter, Nielsen’s 90-9-1 rule introduced us to the notion that the majority of social media content is produced by a small number of people but read by a large number of people. Human nature is such that people who like to express their positive opinions on organizations, brands, or products are drawn to new media in order for their viewpoint to reach a wider audience. Ergo, we have the social media influencers (sometimes called e-fluencers).

As with other elements within this book, the social aspects came first. Advocates and evangelists tend to act in an altruistic manner offering their opinion for no fiscal recompense—that they gain notoriety is generally their reward. However, at the same time as those cunning digital marketers came to realize that some social media writers were open to making a profit from their proclamations, some influencers became more mercenary, seeking rewards that are financial than philanthropic. Although programmatic advertising already allowed the social media influencers to make money by selling advertising space around their content, being offered cash or products to endorse those products increased their bank balance more efficiently.

However, this is yet another traditional marketing tactic that seems to have been (re)-invented by social media marketing experts whereas in reality the practice goes back as far as mankind has traded (give silk to an influential dress designer and soon everyone wants clothes made from the silk you sell). The concept was formalized as such by Katz and Lazarfeld in 1955—though the latter had proposed the concept some 10 years earlier. Problematically, traditional—that is, offline—influencers were always hard for marketers to identify. Online, not only is the opposite true, but marketers can use digital technology to assess influencers’ power by monitoring the blogs, reviews, social media content, and websites created by these online brand advocates. Furthermore, where offline influencers were normally personalities in TV, radio, and print—making them a kind of elite—digital influencers, as Chris Anderson points out in his seminal book The Long Tail (2006), “aren’t a super-elite of people cooler than us; they are us.” This aspect of “are us” is perhaps behind findings in a study by Markerly Inc. (2016) which suggest that—on Instagram, at least—as an influencer’s follower total rises, the rate of engagement (likes and comments) with followers decreases, with 1K to 10K followers seeming to be the optimum. As follow counts rise, it seems the super-influencers are considered to be less like us?

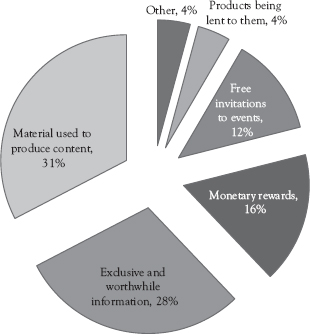

The news for marketers is not all good, however. Influencers have expectations—or is that demands—with many social media influencers seeing their role as being professional rather than amateur. However, in the great scheme of things that is strategic marketing, the sums paid to bloggers who will reach a specific targeted audience in a voice they will respond to is negligible compared to other marketing activities. These fees—usually negotiated by agents and dependent on the number of readers, followers, or friends the influencer has—have prompted the public (and some social media content writers) to see any inducements as little more than bribery for publicity. Figure 3.1 shows the results of research by Roy (2014) which suggests what influencers expect in return for endorsing an organization, brand, or product.

Indeed, from a marketing standpoint many endorsements are little more than adverts—something with which the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has a tendency to agree (note that there are legal issues with regard to the payment of influencers, these are addressed in Chapter 4 (Section 4.5)). That the social media marketer has little control over the influencer’s output, the brand might find itself being cited by the FTC because the influencer has broken the rules.

Figure 3.1 Influencer expectations

Figure 3.2 Subject popularity among advocate bloggers

Furthermore, as is the case with all social media marketing, calculating return on investment can be difficult—engagement does not necessarily translate into purchases. There is also the issue of the quality of the influencer’s followers; are they real or the product of an astute—or dubious—recruitment strategy? Finally, influencers can go from hero to zero overnight (see the example of PewDiePie in the upcoming section on blogging) and, even if the brand can extract itself from the misdemeanors of an influencer, the time and resources put into the relationship are all wasted.

Concentrating on blogs written by influencers (though they use the term advocates), social media marketing solution provider SocialChorus (2014) identified the relative popularity of blog subjects (see Figure 3.2). Note that there is a crossover within some of the verticals—hence the percentage shown amounts to over 100 percent.

SocialChorus also makes the case that if the brand or organization is looking to work with bloggers as advocates then crossovers should be used to their advantage. For example, if you want to work with food bloggers, it would also be advisable to contact healthy living bloggers, consumer interest bloggers, and parenting bloggers for spreading associated marketing messages (Charlesworth 2015). A further observation of these figures would be to suggest that these figures for blogging subjects might well translate to all social media. Perhaps not exactly—but pretty close.

3.3.3 Content Marketing

Defined by the Content Marketing Institute (contentmarketinginstitute. com) as “A marketing technique of creating and distributing relevant and valuable content to attract, acquire, and engage a clearly defined and understood target audience—with the objective of driving profitable customer action,” the concept of content marketing has become increasingly popular in recent years. Like so many aspects of digital and social media marketing, however, no one seems to be absolutely sure what it is. Certainly the model of creating useful content to attract potential customers is not new, but the digital age has moved things along somewhat—not least because it is attractive to the search engine algorithms that have placed an emphasis on the quality of online content. Robert Rose, the chief strategy officer of the aforementioned Content Marketing Institute, gives a more pragmatic clue to what it is in his definition: “Traditional marketing and advertising is telling the world you’re a rock star. Content Marketing is showing the world that you are one.” Perhaps a little more helpful is the definition of Heidi Cohen, chief content officer, Actionable Marketing Guide, who says: “Content Marketing provides consumers with useful information to aid purchase decisions, improve product usage and entertain them while achieving organizational goals without being overtly promotional.” So we kind-of know what content marketing is, and we know the media formats in which it can be published, that is: social media, blogs, articles, white papers, case studies, research reports, guides, webinars, shared documents, podcasts, Q+A pages, videos, forums, and infographics, but clearly there is still the problem of no one seeming to know—or at least they won’t tell us—what content is.

To help, let’s go back to the Content Marketing Institute’s definition, which suggests the content be: “relevant and valuable content to attract, acquire, and engage a clearly defined and understood target audience—with the objective of driving profitable customer action.” Well, that seems to suggest that the content of content marketing is anything the marketer wants it to be. Or should that be: anything the customer needs it to be. That being the case, content is different for every organization, brand, or product and the different markets or market segments that might buy the product. It would seem that developing content for content marketing is not as simple as it may seem. At this point I will direct you to Chapter 5 (Section 5.1), where the issue of appointing the right staff is addressed. I will conclude with one tip that is pretty much universally accepted. Content must not be sales copy. For example: “our widget is the greatest widget in the world and it will more than match the performance of our competitors. Buy it now and get the accessory pack free” is not the content of content marketing.

3.3.4 Paid, Owned, and Earned Media

A concept popular in digital marketing whose popularity is as a result of the impact of social media is that of Paid, Owned, and Earned media. Like many concepts, the practice has existed for as long as mankind has traded goods for reward, but it is only recently that it has been given a name—and it is one that has its roots in the non-marketing marketer phenomenon in that it is heavily dependent on technologists and automation. Many argue that its swift rise to prominence is being followed by an equally swift decline—indeed, this could well be yet another of those concepts that look good in theory but are rarely used in practice—and when they are, it is as a guide rather than strategic tool. The three elements are:

• Paid (also known as bought). Marketing in any media where the promotion is paid for by the selling organization. Effectively, this is advertising on any media including TV, print, and the Internet as well as direct mail.

• Owned. Any media where the product, brand, or organization has control over that media and/or the content in it. This includes such things as brochures, retail outlets, websites, and—to a limited degree because the platform is not owned—social media marketing sites such as Facebook.

• Earned. The product, brand, or organization is deemed worthy of custom and/or loyalty from consumers based on the organization’s way of doing business (e.g., offering excellent service as the norm) which generates consumer-generated content in social media—the reason the concept is prominent in digital marketing.

Perhaps in an attempt to revive an ailing patient, some commentators have added a fourth component; shared. However, this refers predominantly to social media shares, and so is seen by many as an extension of either owned (a post by the organization is shared by users of the platform) or earned (a complimentary post by a customer is shared with other users).

3.3.5 Blogging

Although both the popular and trade press consistently refer to the likes of Facebook and Twitter when extolling the virtues of social media marketing, it is blogging that can get the marketing message across more effectively. As Brown and Fiorella say in their book Influence Marketing (2013): “blogging offers the medium where a brand can be truly itself and offer the exact messaging for which it wants to be recognized and respected.” A more forceful endorsement for blogs over other social media platforms comes from digital marketing maven Debbie Weil (2009). She says: “Corporate blogs are your digital hub—the home base or mother ship for all your social networking and online communications.” She also emphasizes that “As seductive as Twitter and Facebook are for instant communication, you don’t control the service … they own the platforms,” a point I make rather forcefully in Chapter 5 (Section 5.3)—that the section is titled my house my rules should give you the gist of how much I agree with Ms Weil’s statement. I also agree with her when she says that people “should not get hung on the word blog,” suggesting that social site as a better term. I often ponder that the present generation of wonder kinder social media marketers eschew blogs simply because the term comes from the previous century and so is not hip enough for them? And finally, if you doubt her credentials for making such statements, just type “Debbie Weil” into Google (or any other search engine—they do exist apparently).

Common versions of commercial blogs include the following:

• The company evangelist: a less formal presentation than corporate literature or even website, this suits organizations where a culture of staff participation and involvement is paramount. The passion of the writer plays a big part in imbuing a feel-good enthusiasm to the reader. The blog could be used to talk about new products, uses for existing ones, or problem solving.

• The product blog: although this can become more akin to

an online community, such a blog can lead the conversation about product uses and attributes whilst still allowing users to respond via the feedback facility.

• The CEO/director blog: more formal than the company evangelist, but still comparatively informal, this is perhaps the most difficult to get right. Success or failure is often down to the personality of the writer. Ghost writers can be used—but these are easily uncovered if the content doesn’t ring true.

• The event blog: these are not permanent, but are used in the run-up to, or during an event or as part of a wider promotional strategy.

• Press releases: any blog might include these as a quick, and relatively inexpensive, way of making news available to both the general public and media professionals. However, care should be taken to ensure the PR fits with the nature of the blog content.

• The promotional blog: this is the kind of blog written by small-business owners or managers. Popular at one time, social media platforms such as Facebook have replaced many of them—although they can still be used to promote the writer’s expertise in the industry or market.

As will be made clear in later subsequent chapters, it is the nature of the industry, market, product, and—most importantly—the culture of the organization that will ultimately dictate how appropriate it is for the organization to include a blog as part of its digital marketing.

A recurring theme throughout the rest of the book is that like all communication that represents the organization, brand, or product its content must be considered carefully, as does the issue of who will develop and write that content. For the commercial organization, a blog would be a permanent, almost full-time, job for a member of staff, plus backup to cover holidays, illness, and so on. In some organizations, outsourcing the blog to a professional or agency might be the best option. Leaving the global reputation of the organization to an unskilled member of staff is not good practice. For not good practice, read: potential social media disaster.

3.3.6 Consumer Reviews and Feedback

I frequently put forward an argument that the most significant impact that the Internet has had on both consumers and sellers is in the way in which it enables the general public to present the world with their own comments about products and services they have purchased or experienced. I also make the same argument that other aspects of the Internet should not belittle the role consumer reviews have played in changing the way businesses function and their attitude toward meeting the needs of their customers. I would certainly argue that, of all the elements of social media marketing, reviews have had the biggest impact—definitely more than the press’s darlings: Facebook and Twitter. Naturally, this means I wholeheartedly concur with Andrew Keen, when he suggests in his book The Cult of the Amateur (2007) that the ability of the buying public to reach such a large audience presented a “real and present danger” to the established business culture.

It is important to differentiate between the general public giving their review of a product and the role of marketers in the subject of customer reviews. One discussion I frequently have with my digitally obsessed students is that if a company offers customers the product they need, in a place they need it, at a price that is agreeable to them; and this after making the customer aware of the product and its price in a timely fashion, then customer reviews are nothing to worry about as—if any are given—they will always be positive.

Just in case you missed it, I said that if you get the marketing mix (the 4Ps) right, you’ll do alright in business. OK, so that’s rather simplistic, but then marketers do have a habit of making simple things complicated. If nothing else—as I alluded to earlier—the fear of bad reviews has prompted (forced?) businesses to improve their product or service offerings, which means getting the 4Ps right.

That customer-generated reviews impact on fellow consumers in their buying process has been proved beyond reasonable doubt, with buyers trusting consumer reviews more than professional reviews, which are perceived as being part of the marketing of the product. This trust of people like me is based on the psychological phenomenon (mentioned in the previous chapter) of social proof. The concept suggests that people look to what others are doing for reassurance—the assumption being that others possess more knowledge or are better informed than they are. As is my wont, I’ll throw in a caveat that will become more common, and with more emphasis, as the pages go by. That caveat is this. We do not seek help, reassurance—call it what you will—for every product we buy. Indeed, if the calculation was based purely on the quantity of our purchases we seek reviews on a very small proportion of what we buy. Disagree? Try compiling a list of your purchases for the last week. Then cross out those you purchased without referring to a review. You should have deleted pretty much everything us marketers call convenience (or shopping) products. That’s probably just about everything under, let’s say $5. Possibly $10? Possibly $20? Indeed, the cost of goods plays a big part in whether we seek the advice of others or not. The higher the price, the more research we do. But then that’s not exactly rocket science is it? And yes, I do appreciate we can all (a) spend an inordinate amount of time deciding on whether or not to by something for less than a dollar (a pound in my case), or (b) buy expensive products with the heart not the brain that is made without due care and consideration (at least one car in my case). However, this section is on the use of reviews, not buyer behavior per se.

On the issue of who writes reviews I’ll remind you of Nielsen’s 90-9-1 rule (again). Perhaps the proliferation of opportunities to leave reviews has moved the “1” up a bit, but it is still a minority of buyers who leave reviews. Note that for the sake of this book, I am invoking the grammatical difference between reviews and feedback. Although related, feedback is far less critical or thorough. As an example: we’ve all simply ticked the feedback boxes on eBay (haven’t we?) but that is not a review of either the seller’s service or the product. Indeed, how many of us have ever completed an eBay or Amazon product review? Not me.

So why—or when—do we leave reviews? Contemporary thinking, supported by psychological research, is that review writers are predominantly motivated by goodwill and positive sentiment, that is; when we are very happy with our purchase. Conversely, extreme disappointment of a product or service might also prompt us to take some of our own time to make a comment. Interestingly, positive comments are generally written as a thank you to the seller and negative comments as a warning to potential buyers. Persuasion to write a review can also be affected by (a) our level of commitment to the product, brand, or organization—we thank those we feel we have a relationship with, (b) our expectations of the purchase—reviews on expensive products are often nitpicky, (c) the price of the goods—I ignored the request for feedback on a 75 pence/cent household bulb I had purchased, and (d) what’s to review—I was recently asked to review the car park I used at a local airport; “I arrived, I parked, I left.”

For marketers, options for the use of consumer reviews boil down to (a) hosting reviews on the organization’s own web presence—normally its website—and responding to them or (b) taking advantage of reviews on other sites. The obvious difference is that in the former the organization has control over any comments while on the latter it has little or none. For the reviews that are on a web presence controlled by the organization there has to be an emphasis on encouraging users to add to the reviews—hopefully good ones (see previous comments regarding getting the marketing mix right).

Indeed, it might be argued that the key role for the digital marketers in consumer reviews is to encourage customers to actually leave comments or feedback on a review facility. Service providers such as restaurants have any obvious advantage in that there is personal interaction between all customers and staff and so verbal request can be made. Other businesses do not have the same customer contact and so any personal appeal to them must be deliberate and planned. The obvious problem being that if the customer feels that a request for their feedback is insistent, intrusive, or simply too overt, then the result is the opposite of the desired effect. Adopting a phrase that dates back to the early western movies where the good guys wore white hats and the bad guys black hats (and commonly used in search engine optimization) there are white hat methods of collecting reviews and those that are black hat. And there are some that are somewhere in-between, though I can’t remember cowboys ever wearing gray hats.

|

Top of the black hat tactics is offering any kind of payment for a positive review—this could be by way of straight cash, or a discount on a product or service. |

|

Offering free gifts might encourage customers to leave a review—but the gift may well tilt them toward that review being positive. Similarly, friends and family are easy to communicate with to request reviews—but they are hardly likely to give a bad one. I think you can probably guess that this is considered a black hat area by some folk. |

|

Asking customers for genuine reviews—this could be via e-mail, social media, printed leaflets, or facilities at the point of sale or service. Of course, you could ask face-to-face, but hovering over a customer as they write a review would move the request into the gray category as few folks will criticize people face-to-face. |

(Charlesworth 2015).

A final section on this subject is that of readers’ comments on social media pages. I have included it here but it could be in a number of sections in a number of chapters, not least in Chapter 5 (Section 5.3) that considers the control social media platforms have over its users. This chapter is on social media marketing, but there is a crossover with the use of societal social media. If we start with the latter, it has become common for users to leave comments that are either (a) not connected with the subject of the post, (b) abusive, (c) a combination of the two, or (d) an advert for themselves or something that they will benefit from the sale of. For examples of (a), (b), and (c) pick any music track you wish, search for it on YouTube and while the video is playing read the comments beneath it. Quite why anyone who abuses another who has given positive comments about the song is on the page in the first place is a bit of a mystery—simply the opportunity to abuse anyone for anything has to be a possibility. But the comments go off on tangents to the tune and its performers. Just about any song from 1963 to 1974 has the potential to attract Vietnam War comments, for example, which will extend into the Gulf Wars, which in turn tend to attract racial comments. Reading such threads is not a pleasant experience. In 2009, writing for the UK’s Guardian newspaper, journalists Paul Owen and Christopher Wright described this kind of user comments as:

Juvenile, aggressive, misspelled, sexist, homophobic, swinging from raging at the contents of a video to providing a pointlessly detailed description followed by a LOL, YouTube comments are a hotbed of infantile debate and unashamed ignorance—with the occasional burst of wit shining through.

The advert comments (with an outgoing link) can be posted individually by users, but are more likely to be automated. I suspect you’ve all seen them; they are usually telling you that you could earn a zillion dollars an hour doing something or other that requires no skill whatsoever.

Certainly, trolls exist on personal sites, but of more relevance to social media marketers is this type of comments when left on commercial pages. In this instance I am considering the social media content of individuals who are also brands where their social media comments are part of maintaining their brand awareness in the marketplace—even if they are noncommercial in nature, that is: “I’ve just had a shower” rather than “my new album is on sale next week.” There have been a number of high-profile exits from social media, with celebrity-for-many-reasons Stephen Fry being one. Far, far more eloquent than me, I’ll let Mr Fry tell why he quit Twitter in 2016.

Oh goodness, what fun twitter was in the early days, a secret bathing-pool in a magical glade in an enchanted forest. It was glorious “to turn as swimmers into cleanness leaping.” We frolicked and water-bombed and sometimes, in the moonlight, skinny-dipped. We chattered and laughed and put the world to rights and shared thoughts sacred, silly and profane. But now the pool is stagnant. It is frothy with scum, clogged with weeds and littered with broken glass, sharp rocks and slimy rubbish.

To leave that metaphor, let us grieve at what twitter has become. A stalking ground for the sanctimoniously self-righteous who love to second-guess, to leap to conclusions and be offended—worse, to be offended on behalf of others they do not even know.

Even Swedish gamer Felix “PewDiePie” Kjellberg, who is famous only for being a superstar YouTuber with more than 30 million subscribers, told his followers—the Bro Army—in 2014 that he had disabled comments on his channel because they were “mainly spam, it’s people self-advertising, it’s people trying to provoke.” Perhaps it was all part of his own self-marketing, but comments and actions by the people who were—effectively—YouTube’s bread and butter prompted the video platform to address this issue (Mr. Kjellberg pushed his luck too far early in 2017, with his series of anti-Semitic comments resulting him being dropped by Disney and having YouTube pull his channel from its Google Preferred advertising). Which segues nicely into the reason this subject is in this chapter. January 2017 saw YouTube introduce a new source of income for creators (and so, YouTube also), a service dubbed Super Chat, which let fans pay to have their comments pinned to the top of YouTuber live-streams. I feel brand posters such as the aforementioned Mr PewDiePie might see this as an ill-disguised inducement to keep their comments section enabled. Or should social media marketers simply see this as another way to get those millionaire-in-a-day ads in front of gullible members of the population? I struggle to see any value in legitimate marketers using such tactics. Indeed, I wonder if Super Chat still exists by the time you are reading this.

3.3.7 Social Networking and Online Communities

Apology: throughout this section I refer to Facebook as an example. Yes, I know there are other network and community platforms out there, but Facebook is the market leader and I cannot believe that anyone reading this book has not only heard of Facebook, but is aware of how it functions.

As I promised when it was first mentioned in Chapter 1, it is relevant at this point to remind you that Facebook is (a) not part of social media, it is an entity that exists to facilitate social media, and (b) it exists to make money for its owners and shareholders. The same goes for all social media platforms.

Nonetheless, any marketer or business person would doff their metaphorical cap at the way in which the likes of Facebook and LinkedIn have developed their product offering (the provision of web space to be used by members) to such an extent that they dominate the industry in such a way that organizations feel they must not only use their services, but advertise that service on the organization’s own products, stationery, vehicles, and websites. Kudos to them for that. Indeed, such is the dominant nature of Facebook that some customers would rather visit the web presence of an organization, brand, or product on a third-party platform than on the website of that organization, brand, or product. Furthermore, the organization, brand, or product chooses to use that third-party platform—over which it has no control—to its own online domain. This is not, of course, totally its own choice. That so many of their customers and potential customers have free access to Facebook is a far more attractive proposition than the effort, resources, and money it takes to attract that number of people to its own website. Indeed, the likes of Wal-Mart with its Hub, Anheuser-Busch’s Bud.tv, and KLM/Air France with their Bluenity.com are examples of high-profile brands that failed with their own domain social network sites. However, this is not an absolute and it is likely that as Facebook—and others—change the terms and conditions of use of their platforms, brands will be tempted to move their social media to sites that they own. Note that we will return to this notion later in the book.

So what do social networking and online communities offer marketers? In a nutshell; access to highly segmented customers and a natural platform for interactive promotions and the opportunity to actively engage with their customers that was simply not available to them prior to the Internet in general and social media specifically. John Battelle made this point in his influential—and best-selling—book, Search (2005), saying: “the very idea that our relationships with others (our social network) or our relationships to goods and services (our commercial network) were anything but ephemeral was presumed: without the internet, how could it be otherwise?”

Essentially, the social media marketer has two choices in deciding how to use networks and communities as part of any marketing strategy. The first is to use them as a channel for the dissemination of a marketing message—albeit a message that is disguised as engagement with the customer. Wait; disguised? Yes folks, relationship marketing is a form of marketing. Are you seriously suggesting that employees of an organization would really want a relationship with their customers if it wasn’t part of their job? And—ultimately—their job is to make money for their employers. OK, so there might be some businesses out there that are truly altruistic—but check them out in a couple of years and see if they are still trading. What about not-for-profits? I hear you ask. Well, yes … to a degree. But not-for-profit means no profit to give to shareholders, it does not mean at a loss. The second way in which marketers can use networks and communities is as an aspect of customer care and support. This is covered in more detail later in the chapter.

One thing networks and communities—and probably all aspects of social media—cannot provide the marketer with is new customers, that is; people do not discover the organization, brand, or product on social media having never heard of it before. Remember, this book is on social media marketing, not social media. Certainly, friends might post on their Facebook page that they have bought a new product, it is wonderful, and everyone should buy it, but that is social conversation, it is chitchat, it is water cooler talk … it is not marketing.

Social media is most effective for (a) retaining existing customers by developing and maintaining a relationship, or (b) helping potential new customers as they work their way down the buying funnel of their purchase decision making having been made aware of the organization, brand, or product somewhere else. It is very rare—and then probably by chance—that a potential buyer discovers an organization, brand, or product via its social media presence. Need an example? It is almost certain that before you signed up for your present (and/or past) university or college you will have accessed its official social media presences (there will be other student-developed pages). However, that will be after you have become aware of that university, be that via its marketing, its reputation (marketers would argue reputation = brand = marketing), its prospectus (marketing again), a family member, a friend, or a former tutor or your school or college careers department. A caveat to this (a polite way of saying cover my back) is that Facebook would like Facebook to become everyone’s gateway to the Internet, part of this being that search engines will be replaced by a search on Facebook for whatever it is you are looking for. Such is the power of Google—and our routine use of search engines—I cannot see that happening, but hey, you never know; we got Brexit and Trump.

For developing and maintaining a relationship you could do worse than following the advice given by Facebook itself. The Facebook for Business website (facebook.com/business) suggests that organizations:

• Be responsive.

• Be consistent.

• Do what works.

• Make successful posts into successful promotions.

As we will see in subsequent chapters, it’s not quite as easy as Facebook would like us to think—neither does it suggest what organizations should not do. I would suggest that social media is not a place for comments when:

• The product, brand, or organization is only talking about itself.

• The post is there to meet a quota or predetermined target.

• Replies or reactions are not monitored.

• There is a perceived obligation to post—comments should be posted for a reason, not to feed a habit.

But most important of all:

• They are not genuine.

(Charlesworth 2015)

For helping potential new customers in their purchase decision there are three ways the organization, brand, or product’s network or community social media presence might influence their decision. These are:

1. Provide information that might sway a choice (the product is bigger, faster, etc. than rivals). However, this kind of information is normally sought on manufacturers’ or retailers’ websites.

2. By the nature, culture, and ethos of the presented content the buyer is encouraged to feel an affinity to the product, brand, or organization.

3. The input of the followers is so positive that it encourages purchase.

Network or community campaigns, however, do not have to be focused on the product, brand, or organization. Procter & Gamble, for example, has developed social media campaigns around personal issues that are important to the consumers that the organization wished to engage with—bullying of teenage girls, for example. Similarly, Unilever used social media to encourage women to question their negative perception of their own looks. Again, as a marketer, I recognize the excellence of these campaigns and real-life issues they address—but the campaigns were not wholly altruistic; they encouraged sales of Secret deodorant and Dove soap respectively. Both also used other media extensively—see my early comments on when is social media marketing not social media marketing.

3.3.8 Social Sharing

I have to start this section with another apology; basically, this is the same apology as at the beginning of the previous section—except for this section: replace Facebook with Twitter for text messages, Instagram for images, and YouTube for videos. An addendum to this is to mention that Instagram is owned by Facebook, and YouTube by Google. It’s a small digital world.

As with the networking aspects of social media covered in the previous chapter, defining the various elements of social media is far from being an exact science and so it is for social sharing. Indeed, although I use Twitter as a mainstay of this chapter, there is a reasonable argument for it being in the previous one. Moreover, given that it is sometimes described as a microblogging site, it could also have been addressed in the earlier section on that subject. However, I think that description is nebulous; 140 characters (or 280 as it is now) is not sufficient for a true blogger to express their ideas and opinions fully—only a snapshot of them. Social media marketers should be aware that the classifications I have settled on should be considered imprecise—and all aspects of social networking and sharing could and should be considered interchangeable (Charlesworth 2015).

That social sharing is commonly described as the broadcasting of our thoughts and activities immediately gives rise to the notion that the medium not only has potential as a marketing tool, but that it is closer to traditional marketing than other social media platforms. In a way this is correct as it encourages the sending of brief messages without the engagement expected of networks and communities.

Social sharing can be divided into three different—though related—parts: messages that are textual, those that are images, and those that are in video format. Before considering each in turn, however, there are a number of caveats that pervade all three, and they are:

• Any message sent should not be overtly marketing, social media participants do not like to be lied to, or even fooled. They don’t even like to be marketed at (Charlesworth 2014).

• Every message must be perceived by the receiver as valuable; if it isn’t, they won’t read it. Similarly, quality always trumps quantity.

• In the previous chapter, mention is made of many messages being sent on social media, but relatively few being read. This must be factored in to any expected return on investment for a social sharing campaign.

Although images and videos can also be sent on the platform, text messages are Twitter’s bread and butter. The simplicity of the (original) 140-character message might almost be considered to have been designed for marketers rather than the social use for which it was intended. After all, sales and marketing copywriters have been used to writing to similar constraints for decades. Social sharing also offers marketers immediacy—switched-on social media marketing can react to world events as they happen, though often badly (examples of the good and the embarrassing are included in Chapter 6). From a marketing perspective then, Twitter can be seen as being instant, whereas social networks are more akin to conversations, communities about engaging. Tweets can be used to inform customers of any news, event, product, promotion, or special offer that is appropriate to the sender and its Twitter audience. However, it is the informality of Twitter—140 characters lends itself to abbreviations and text-speak—that is; at the core of its benefit to marketers, allowing them to be perceived as real people rather than faceless brands, products, or organizations.

Image Messages

As with their textual cousins, image-based social media platforms such as Instagram allow marketers to target specific groups of users with their marketing message. Individuals effectively segment themselves by the photos they keep, send, resend, and comment on. Pictures lend themselves to certain markets and industries, with retailers benefitting most. It is also easier to send a picture that is not overtly marketing. For example, a fashion retailer could send an image of a new dress to their target segment with the message: “here’s part of our new range … how good would you look in this?” Sales copy would be: “here’s part of our new range … buy now for free shipping.”

Video Messages

Although Facebook is closing fast—or has already past, depending on which reports you read—YouTube is the main player in social video. Yet again, however, it is important to appreciate that YouTube was set up to show homemade, social videos—the classic dog-on-a-skateboard type of thing. However, rather like eBay’s move from yard sale to host for shops, YouTube is now predominantly the home of professional videos, be they of pop music, clips from movies and TV shows (or entire shows), or adverts shown on—and made for—TV.

As with all social media platforms, users can develop their own space on YouTube where they can post their own videos as well as a selection of the favorites from other sources so that friends can see them. For the organization, brand, or product there is the YouTube One Channel where their own videos can be posted and made available—an additional bonus is that these videos can be embedded on their own website.

Although amateur handheld-camera videos can work for some products or brands, organizations are best advised to use only professional content on YouTube. You might even be surprised at how many of the amateur videos are actually staged by professional film crews because the effect is deemed more appealing for social media. Oh those marketers—they’re a tricky bunch.

3.3.9 Social Service and Support

If it isn’t a statement of the glaringly obvious, this subject refers to the use of social media as a medium for providing service and/or support to customers. Pretty much by definition, this means some kind of after-sales service, and not part of any pre-sales marketing effort—though evidence of such service may have some bearing on a customer’s purchase behavior.

Such service is successfully practiced by relatively few organizations. This state of affairs may well change in the near future as service and support on social media is now expected by some customers or market segments—in particular the generation that has grown up with the Internet who now considers digital to be the norm.

Social service and support can be broken into two facets: proactive and reactive.

Proactive Service and Support

This is where online communities and/or social networks are used as part of the overall package of product or service offered to the customer when they make a purchase with a concentration being on improving the customer experience and so their use or enjoyment of the purchased product is enhanced by this service. The nature of this service lends itself to being conducted in public, where the customers and potential customers can see the good work of the organization.

Reactive Service and Support

As it concentrates on being reactive to events that are normally—almost by definition—negative, this element might be better described as after-sales service and support and is provided as a response to customers’ requests, queries, or complaints. Essentially, this means that the customer experience (the proactive aspect of service and support) has failed and so the customer is coming to the organization via social media for support, or more likely, help, recompense, or to complain. For this reason it is a reasonable argument that interactions with disgruntled customers should be conducted out of the public eye that is social media.

There is a third option for social service and support that addresses reactive service, but it is suitable only for a limited number of organizations, markets, or industries. This is peer-to-peer service and support, though it is better suited to being hosted on the organization’s own platform—for example its website—rather than on third–party platforms such as Facebook. This model is that the organization sets up its social media support platform and then invites other customers to respond to—and answer—questions and issues raised by its peers. It operates best where the questions posed have a finite answer; having peers give advice based on limited knowledge is problematic. However, the notion lends itself to the theories of how and why social media works, creating a sense of community among customers. For the organization a compelling reason for using it is that—so long as it is implemented correctly—it is significantly cheaper than other options such as call centers.

3.4 Social Hosting

This is the flip side to the Wrangler-George Strait example I give at the beginning of this chapter, where the video was made available on an owned platform (wranglernetwork.com), but there have been numerous similar deals where the platform used is a social media platform. Examples include the NBA and NFL Live Streams on Facebook, an obvious collaboration between the sports and social media Goliath. As a side note, a cynic might suggest that Facebook Live was developed for this income-generating purpose and not to enhance the general-public user’s capability to socially communicate. Facebook, however, is not the only platform to embrace this money-spinning concept, with Twitter’s partnership—and that is the correct term—with Seven West Media (SWM), the domestic broadcaster of the Australian Open Tennis being one such example. In 2017 SWM streamed live video and highlights from the Australian Open Tennis Championships. The deal saw SWM deliver video highlights and live footage from the Grand Slam in Melbourne via Twitter. Using the Twitter Amplify platform (“designed to let many more publishers and creators monetize their video content on Twitter, while making it easier for advertisers to reach massive audiences and sponsor great content tweets”3) SWM generated income via pre-video advertising for their sponsors. The summer of 2017 saw media and entertainment conglomerate Time Warner Inc. announce a partnership that includes the development of made-for-Snap shows to be delivered exclusively on the company’s Snapchat platform. At a more mundane—but more visible—level April 2017 saw LinkedIn introduce Trending Storylines—effectively a move to add a news platform to its current role as a networking channel.

1 Thinkbox’s (Thinkbox.tv) video analysis combined 2016 data from The Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board (BARB), comScore, the IPA’s Touchpoints 2016 study, Ofcom’s 2016 Digital Day study, and Rentrak box office data to give a like for like comparison of estimated video consumption in the UK.

2 As did the BBC in the case of Fenton the Labrador (look it up on a search engine of your choice).

3 https://blog.twitter.com/2015/twitter-amplify-now-offering-video-monetization-at-scale