SAFE AND SOUND: PROTECTING YOUR FLOCK FROM PREDATORS

WHEN BUILDING YOUR COOP, think seriously about how to predator-proof the structure and any outdoor spaces in which your chickens roam. Perhaps skunks, raccoons, opossums, or foxes live in the area. Maybe you live near prime hawk nesting locations. It is your responsibility to prevent your chickens from living in fear that they’ll be part of the evening buffet.

In many places, the law protects wild animals, putting your rights as flock owner second. For example, in the United States, it’s illegal to shoot a bird of prey. Unless you are Native American, you cannot remove feathers from any dead wild bird. Why these protections? Because in the past, animal cruelty was a real concern. So although you may be angry that one of these animals attacked your flock, research your rights before you shoot or capture.

Your best bet is to contact your local animal control office or a government-affiliated wildlife biologist. With help from these officials, you can identify the culprit and determine an appropriate action plan. Though fees associated with local services may exist, they’re likely minimal, but will ensure that the relocation of a captured animal follows regulations enforced where you live. Alternatively, if the predator has already made your coop an easy target, you may wish to contact a professional animal-removal service.

Much of the information provided in this chapter stems from our personal experiences with predators and chickens. But we also recommend the Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management (http://icwdm.org/) as an additional resource. This website provides information about track identification, damage to poultry and livestock, and preventative measures to keep out predators.

[ Predator-proof every opening of your coop thoroughly with high-quality wire. ]

PREDATOR-PROOFING

Later in the chapter, we get into specifics about different predators’ calling cards and measures to keep each away from your coop. But first, here's some tips on making your coop a secure place for your birds. (Many of these we touched on in the previous chapter about coops, but they’re important enough to reiterate here.) Remember to safeguard the coop from above, below, and on all sides.

When building a new coop, bury the wire on all outdoor runs at least 18 to 24 inches (45 to 60 cm) down. Most animals give up digging after awhile. As an alternative, bend the wire out into an L shape at least 18 to 24 inches (45 to 60 cm) from where it meets the ground. Does it look pretty initially? No, but eventually grass grows over it or gravel rocks you place around the coop base covers it.

If possible, cover all outdoor runs with solid roofing to prevent contact with wild bird feces and attacks from aerial predators such as hawks or owls. Also, a solid roof provides shade and shelter for your birds. If a solid roof is a no-go, cover the pen with 1-inch (2.5 cm), double-knotted aviary netting. (The 1-inch [2.5 cm] netting is better than the 2-inch [5 cm] because the latter allows wild birds entry.) Place the netting higher than the tallest family member who enters the run.

When building your coop’s indoor floor, whichever type you choose, install a 1/4-inch (2/3 cm) hardware cloth beneath. This prevents entry by rodents that decide they want access to your coop by chewing through the floor. However, this preventative measure does not stop them from digging tunnels under the coop or making a home there. (You’ll have to put out traps or bait should you find a rodent tunnel leading under the coop.)

Secure heavy-gauge wire around your chicken run, burying it 11/2 to 2 feet (45 to 60 cm) below the ground.

PREDATOR CALLING CARDS

In many—though not all—cases of predation on a flock, the predator leaves behind telltale signs. As the flock owner, and therefore protector, it is up to you to examine the remains (while wearing gloves, of course) to determine which critter caused the damage to your flock. A predator who is successful the first time around will likely return.

The descriptions that follow may not seem characteristic of what you see on your farm post-attack. We’ve done our best to describe typical behaviors, but not every animal in a species acts in the exact same way. Also, young or sick animals out on their own may be more persistent or desperate in their feeding habits because of their extreme hunger, meaning they’ll likely come back to a coop with minimal or poor predator proofing.

WOUND CARE

If your chickens are attacked by a predator, you need to act quickly. First, isolate the wounded bird—most likely the chicken will be in shock. Place clean gauze or a clean towel over any wound that is actively bleeding. Wrap the bird in a towel to restrict its movements and place it in a dark box (with air holes) so you can transport the chicken to your nearest veterinarian. Chickens have many delicate and thin-walled air sacs throughout their bodies that are a part of the bird’s respiratory system. There is the risk of a predator puncturing one of these air sacs. Not only is there this risk, but birds are unique in their anatomy and medication requirements. Always seek a veterinarian’s expertise in times of trauma.

Canines

This predator group includes wolves, coyotes, and both wild and domestic dogs. Coyotes typically kill with a bite to the neck and disembowel the fowl. Wolves operate in much the same way. Dogs are less efficient and bite at the whole bird, but they do not consume much flesh. All three of these groups typically leave behind dead birds.

If you suspect a canine, look for footprints. A domestic dog’s footprints vary depending on the breed but average about 4 inches (10 cm) in length. A coyote’s are smaller (3 inches [8 cm]) and more compact. The footprints of a wolf measure approximately 5 inches (13 cm) long.

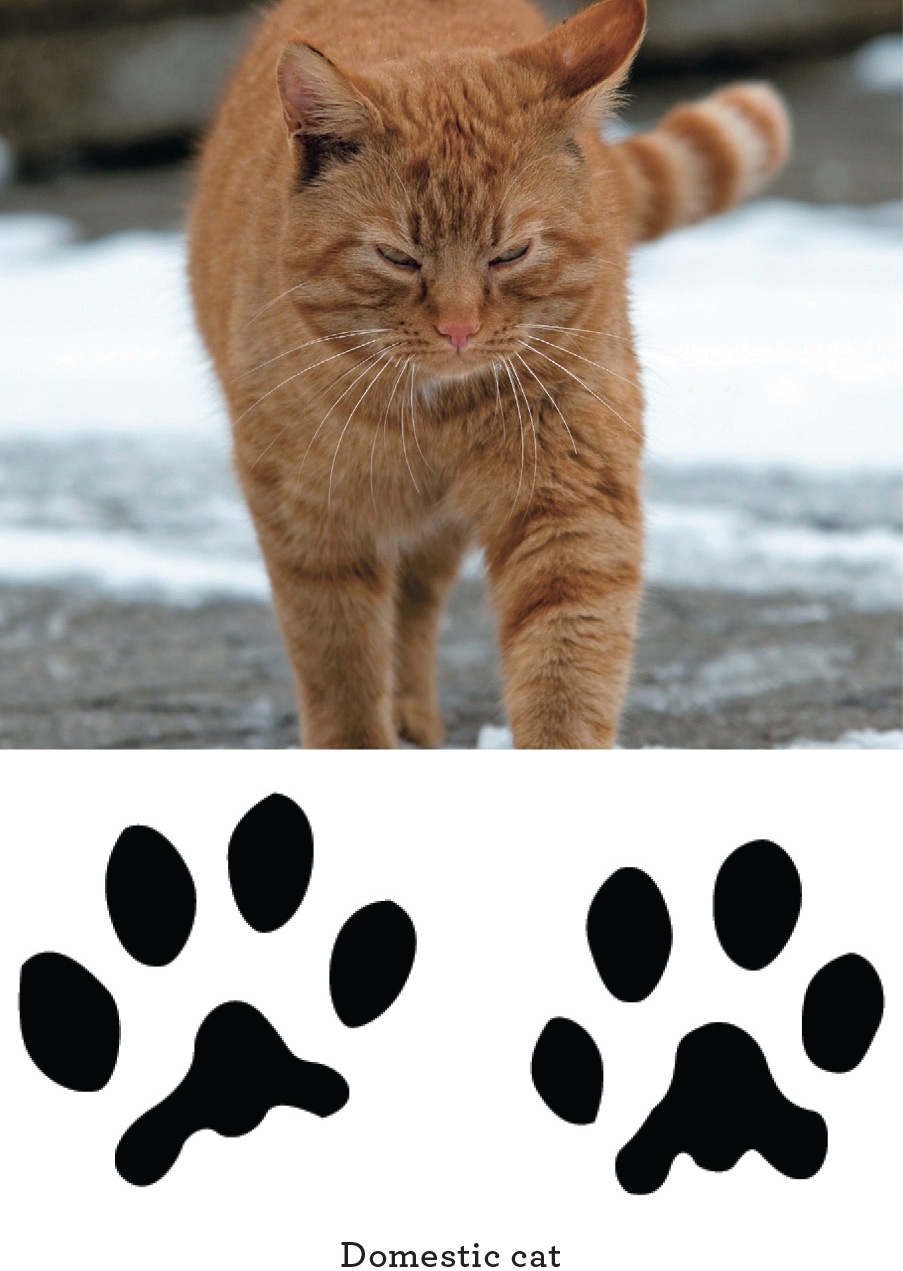

Cats

Cats, both wild and domestic, are messy eaters that leave pieces of their meal strewn about in a wide radius from where they actually dine. They eat the meatiest parts of the bird, leaving the skin and feathers intact. They also tend to leave tooth marks on the birds’ bones.

Foxes

Have you heard the phrase, “Fox in the henhouse”? It usually means that someone is up to no good—the precise behavior foxes, both red and grey, exhibit when going after your chickens. Foxes prefer poultry as a food source and kill with a bite to the neck. Usually, the animal leaves no evidence behind, taking the whole bird back to its den. All you may find are a few drops of blood or a few feathers.

Typically, a carcass left behind by a fox has curled toes because the fox stripped the meat from the leg bones. Or it partially buries the remains. A fox is a serious problem for your chickens because if it successfully raids a coop, the fox will surely come back the next day. Check for and repair any holes in the coop and look for fox tracks, which look similar to that of a dog, wolf, or coyote.

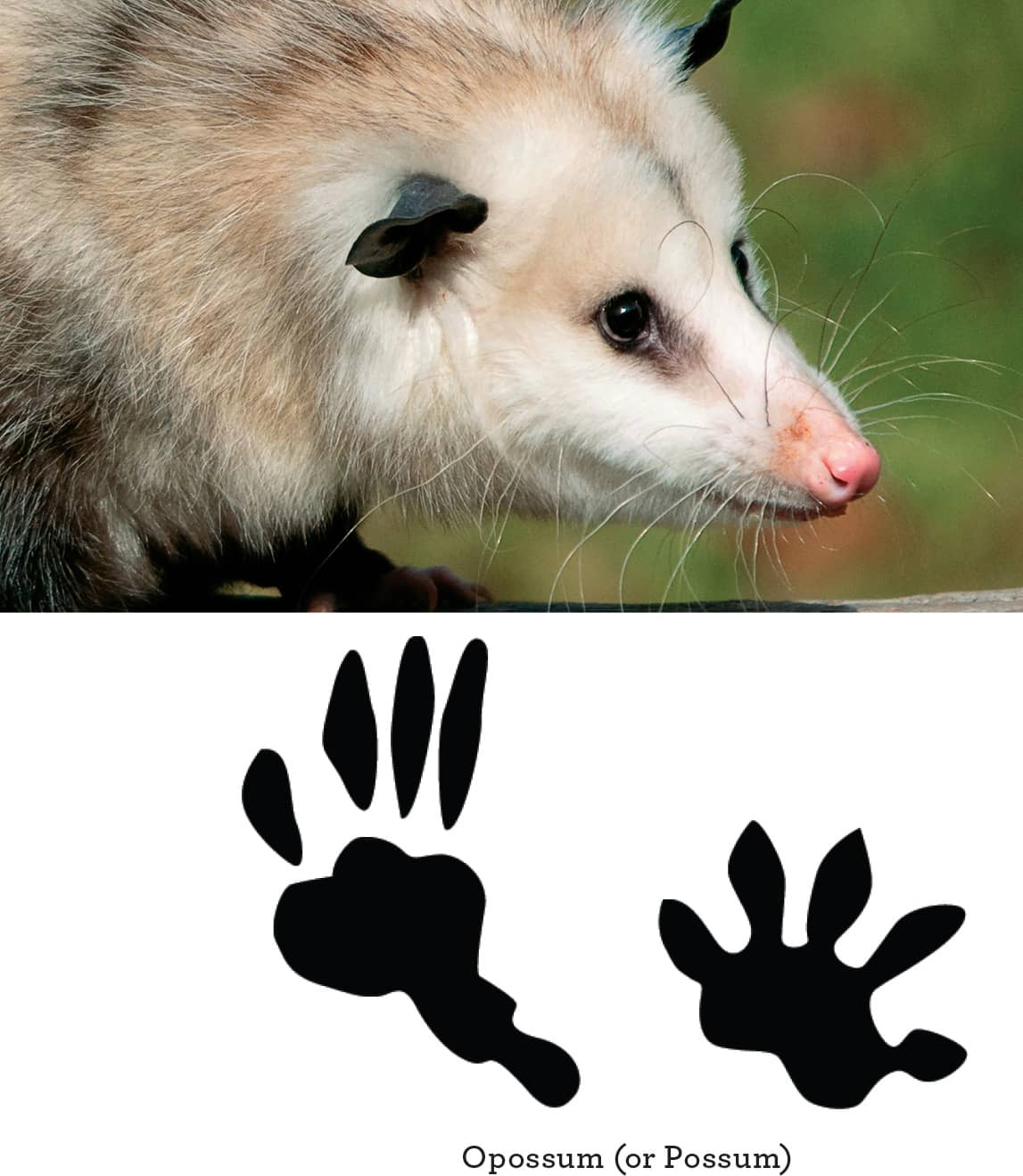

Opossums

Opossums occasionally raid a chicken house, often taking a single bird at a time and clumsily mauling it. Opossums tend to feed on the bird starting at the vent or consume young poultry whole, leaving behind a few wet feathers. They’ll also eat eggs left in the nest. You’ll find eggs smashed and strewn about, often with just small pieces of shell remaining. Opossums may also come in just to eat the grain or feed in the feeder.

If you think you have had a recent visit by an opossum, smell around the coop. Does it have a musty odor? That’s an indication of the animal. Also look for its tracks, which are unique, short in the front (2 inches [5 cm]) and long in the back (3 inches [8 cm]). The rear footprints have an elongated outer digit that looks almost like a thumb.

Raccoons

Raccoons are troublesome predators because they are smart problems solvers, returning night after night to test your coop’s defenses, sometimes chewing through an outdoor run’s aviary netting. (If for no other reason than to protect against raccoons, we strongly recommend a well-built coop and outdoor run with a solid roof covering.) Raccoons can pry chicken wire from staples, so make sure your chicken wire is strongly secured to flat surfaces.

Raccoons enjoy a varied diet that includes meat, fruits, and vegetables. That means they’ll certainly come after your chickens. These masked bandits have no qualms about taking several birds a night from your coop. How can you tell if a raccoon’s been by? The breast and crop of the dead bird may be chewed on. Also, the entrails may be eaten. Plus, raccoons are fastidious about cleanup, often using a nearby water source to wash up. In the coop, this means the waterer, so look for bits of feather or flesh in or near your chicken waterer. Finally, raccoons also consume chicken eggs, taking them a short distance away from the nest to eat.

The tracks of a raccoon are distinctive. These animals have five toes arranged much like a human hand. Also, raccoons have an interesting gait, leaving tracks that show the left hind foot aligned with the right fore foot.

Weasels, Mink, Fishers, and Other Mustelids

In some places, mustelids (e.g., weasels, martens, minks, and fisher cats) are a problem for chickens. When they get into the coop, they often eat just a chicken’s head, leaving the rest of the body intact. They can kill many birds in a single evening. And eggs are not off limits either. An egg eaten by an animal in this group typically has a 1/2- to 3/4-inch (1 to 2 cm) opening at one end and possibly tooth marks. Look carefully at the egg to see the finely chewed ends.

Rats

Rats are inclined to take small chickens, especially chicks, killing the bird by biting at the back of the neck. They also tend to relocate chicks back to a burrow or hole to eat. A rat will consume less of a bird that’s too large to fit in its hole, but will try to conceal the carcass somewhere nearby. Look for rat feces as an indicator that these animals are around.

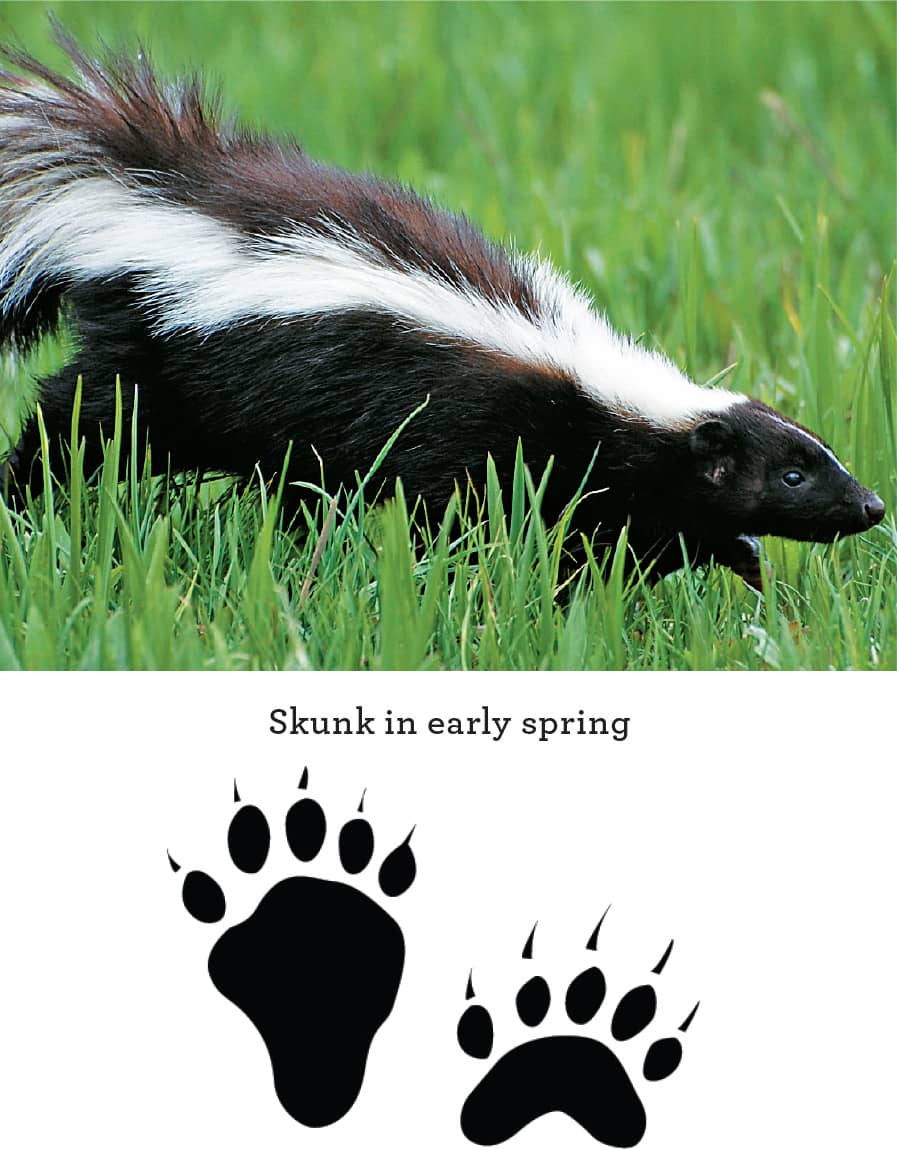

Skunks

Skunks, as we all know, have a characteristic smell. If you enter a coop shortly after one has departed, you may catch a slight hint of its scent. Though these black-and-white animals, cousins of minks and weasels, tend to leave adult birds alone, they will take one or two smaller birds in an evening. Be aware of their telltale signs: They maul the birds a great deal. Or they take a bird’s carcass back to a den site, leaving no trace. Skunks also eat chicken eggs, robbing a nest of its contents and moving no more than 3 feet (1 m) away to eat. An egg eaten by a skunk typically has one edge pushed in (this would have enabled the skunk to stick in its nose and lick out the contents). For incubated eggs, the skunk may chew them into small pieces.

Snakes

Snakes of all kinds do come into chicken coops, but they leave little evidence of their visit, often swallowing eggs or chicks whole. Sometimes they shed their skin, dropping it in the coop. They need an entry-exit point large enough to pass through after eating, so block all such entryways using rat wire or 1/4-inch (6 mm) wire mesh. Finally, snakes may remain at the scene of the crime so reach into the nest box with caution. In other words, always look before you reach.

Snakes are excellent climbers and a particular threat to eggs and chickens.

Aerial Predators

Hawks, eagles, owls, vultures, and other birds of prey can quickly and easily enter and exit a pen not covered with aviary netting. And if they don’t perceive you as a threat—for example, if you’re sitting reading a book and not moving much—they won’t be afraid to swoop in and take birds only a few feet or meters from you in the yard. Eagles are large enough to carry a bird of any size; hawks and falcons can take all but the largest rooster and hen breeds. Black vultures occasionally take chickens, though not too frequently. Owls hunt at night and fly silently. They feed mainly on rodents but can capture and carry off chicks with ease. If you notice your chickens being taken with great frequency at night, look for an owl nest nearby.

Some birds of prey, if they feel comfortable, will not fly away after killing your chicken. They will pull out feathers to reach the skin and flesh.

Flying predators, such as this hawk, can swoop down in a matter of seconds. They are a major threat to your flock.

THE WALK-AROUND

Walk around your coop perimeter daily to look for predation attempts. Signs may be as obvious as a hole, scratches on the door, footprints, or feces. If you happen upon a predator in your coop, keep in mind that it is a wild animal. It may also be sick and the risk of it biting you is high if you’ve interrupted its mealtime. Remember, you may not be able to tell that an animal is sick simply by looking at it. The worst possible scenario is meeting a rabies-infected predator. No matter the scenario, allow the predator to leave quietly. If you come across a bird that has been attacked, use caution when handling the remains. Assume a sick animal was the perpetrator and always wear gloves to handle the remains.

Once a predator attack has occurred, focus your efforts on preventing future attacks and repairing the coop.