ILLNESS AND AILMENTS: PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

NO FLOCK OWNER WISHES illness on any flock member. Chickens are like any pet or member of your livestock family, meaning you should always have their health in mind. When the family cat or dog becomes ill, what do you do? Head to the veterinarian, of course! It is an expectation and responsibility that comes with owning a pet.

Because chicks cost so little to purchase and maintain, some non-chicken owners may consider them expendable. But you, on the other hand, likely consider them integral members of the family. Know this then: Veterinary care for poultry—or any avian species, for that matter—is among the most costly, and poultry diseases are some of the most difficult to diagnose. Therefore, preventing your chickens from getting disease should be a top priority.

[ Chickens, like all of your livestock, need reliable medical care. This rooster is suffering from scaly-leg mites. ]

BIOSECURITY

Prevention comes in the form of a somewhat intimidating word: biosecurity. This term simply means “life” (bio) and “safety” (security). For flock owners, it means a daily set of preventive practices that you do to reduce the risk of disease transmission to your flock.

Regardless of your flock size, do not let this word or the measures it requires alienate you. In fact, owners with smaller flocks are potentially more powerful in enforcing biosecurity than many large-scale livestock producers. Simply put, you have fewer birds, you know their favorite activities, and you interact with them daily. Commercial operations still use the same principles, but apply them on a significantly larger scale. You can control exactly how much exposure to disease—if any at all—you are willing to take.

Disease-Carrying Entities

How can you ensure that your flock members remain free from illness? How does disease enter your flock? Once you know your disease-causing enemies, are you willing to shut down all access points? To start, let’s look at some of these disease-carriers.

WILD BIRDS

Though they are not predators of your flock, wild birds are some of a healthy flock’s greatest enemies. As flock owner, it is your responsibility to prohibit contact with wild birds as much as possible. This is when many owners become disenchanted with the idyllic notion of keeping chickens. Doesn’t every owner dream of letting her chickens roam free? Aren’t the birds happier and healthier when they do? True, chickens enjoy adventure, but remember, they are birds that originated in the bamboo forest in Southeast Asia so they crave a certain amount of protection.

Wild birds’ feces not only carry countless viruses, bacteria, and protozoa, but their bodies also host internal and external parasites.

Here’s why that’s problematic: Many wild birds are opportunists, which means they’ll take advantage of an appealing-looking coop for both shelter and food. Your biosecurity goal is to prevent these behaviors. In other words, stop wild birds from roosting in the coop, stealing feed meant for your chickens, and potentially leaving behind disease-laden feces.

To do so, fence out the wild birds using chicken- or pigeon-wire and solid roofing. Relocate birdhouses and feeders so they’re as far away from your coop as possible.

Consider birdfeeders permanently disease-prone, to be handled after daily care of your chickens. If wild birds do get into your coop, remove their feces as quickly as possible; chickens naturally peck at interesting objects—that can include wild bird feces.

Turkeys, ducks, geese, and chickens: Keeping multiple species together is an in invitation to disease that can cross the boundaries of a single species.

Either you or your veterinarian can vaccinate poultry.

RODENTS

Once rodents find a safe place with plenty of food, they stay put. This is problematic because they carry organisms in their hair and feet. Their intestines produce thousands of disease-causing organisms. (Interestingly, a mouse does not have an anal sphincter, and therefore leaves droppings around its most highly traveled routes.) Mouse feces contaminate feed and water sources, and chickens eat these feces out of curiosity. In a single twenty four–hour period, one mouse can excrete, on average, 100 fecal pellets, each of which may carry up to 230,000 Salmonella Enteritidis organisms (we get into more detail about salmonella shown here and here).

Keep food inaccessible to rodents. That means cleaning up spills and storing feed in a metal trashcan with a tight-fitting lid. These bins keep out rodents for a time but not forever.

Rodents have incisor teeth that never stop growing, requiring that the animals grind them down by chewing. They can chew through wood, cinder block, and yes, metal, so check the feed room, the coop, and your metal trashcans weekly for holes. Mend rodent holes immediately, with 1/4-inch (6 mm) wire mesh.

Also, examine your coop and feed room for rodent feces and remove them immediately; then wash your hands.

Disease organisms can survive in the earth and become a serious threat to your hens and chicks.

PREDATORS AND DISEASE

Predators not only bring in zoonotic organisms on their feet and fur, but also in any feces they leave behind in the coop. (In chapter 8, we discussed predator-proofing your coop.)

The biggest concern for the average flock owner is a predator found within the coop. Although chickens cannot get rabies, a human can. If you come across a predator in your coop, leave it alone. Never attempt to remove it or you risk being bitten. Seek the services of a qualified individual.

Once the predator leaves, you need to remove any bird carcasses. Always wear gloves to do so. If a chicken that was attacked survived the ordeal, remove that bird to your quarantine area until it is again well. Always err on the side of caution.

HUMAN SHOES AND CLOTHES

What evil lurks on the soles of men? Dust, dirt, rocks, mud, even leafy debris can surround and even protect a virus, bacterium, fungus, or other disease-causing organism. The same goes for clothing. You and your guests should change out of street clothes before entering your coop. Everyone should walk through a disinfecting footbath to prevent a disease from waltzing right in.

Keeping Disease Out

Now you know some of the ways diseases can get into your coop. Here, and shown here, we’ll discuss how to keep them out.

PHYSICAL BARRIERS TO ENTRY

It is your responsibility to avoid exposing them to disease by providing them with great living conditions. A well-built coop with a secure door protects against diseases brought in by wild birds, rodents, predators, and uninvited humans. Part of this includes a fence, which not only keeps your flock in check, but also keeps out unwanted predators. A good coop protects your flock from ground and airborne predators. (For more information about specific predators, turn back to chapter 8.)

COOP-SPECIFIC CLOTHING

As we mentioned above, disease-carrying agents can cling to clothes and shoes. Have dedicated clothing for when you feed and care for your flock. Wash these items weekly. Also, if possible, use a dedicated pair of boots that you can scrub weekly or wear in a footbath. A footbath can be made from a container such as a litter box filled with a disinfectant solution, and you can walk through it to prevent tracking in disease. You can always wear coveralls when you visit the coop.

QUARANTINE AREAS

Quarantine all new birds for two to four weeks in isolation before placing them with your flock. This ensures that if a new bird is carrying or comes down with a disease, you will not immediately expose the rest of your flock to the problem.

It is never a good idea to introduce new birds to an already existing flock because some birds may be disease-carriers without exhibiting symptoms. Those birds can still infect your flock. The more closed you keep your flock, the less chance you have of letting in disease.

A well-built coop is worth the time, planning, and cost to ultimately protect your brood. Secure doors and windows, a functional locking system, proper lighting, and ventilation are only a few of the amenities necessary to consider in your overall design. See the illustration shown here for more detailed information.

CLEANING

Disease does not need an animal host to gain entry to your flock. Dirty or contaminated equipment can house disease organisms. Clean and disinfect all equipment that enters your property. For that reason, we advise against borrowing a transport or carrying cage without thoroughly cleaning and disinfecting it first. Here's the bottom line: Keep clean everything that touches your birds.

TRAFFIC PATTERNS

If you have experienced disease outbreaks in the past, ask yourself, “Did I do something to cause this?” Think about it like this: Usually, everyone’s first morning task is to grab the food and feed the birds. That means everyone heads first for the feed room (which makes it a great place for a footbath, by the way) but where to next? Perhaps after leaving the feed room, rethink your normal path instead of caring for the nearest birds.

Feed and take care of your youngest birds first, and then move to the older birds. Though it may go against intuition, care last for the birds held in your sick pens or in quarantine. This prevents spreading the disease further among your flock members. Keep the equipment for birds in the quarantine area completely separate and make it obvious to others who handle the chickens (for example, place a red piece of tape or a red marker around quarantine area equipment).

DISEASE DIAGNOSIS

Birds hide illness as long as possible. It’s in their nature. In the wild, predators dispose of birds that show signs of sickness. If not killed by predation, these birds are ostracized by their flocks. They also are the last selected for mating purposes. Therefore it behooves them to look and act as normal as possible for as long as possible.

By the time you notice illness in a bird, it may have already disseminated virus, bacteria, and other germs to the rest of the flock. This bird still needs you as its advocate.

First: Isolate it immediately.

Second: Examine the rest of your flock for signs of illness.

Third: Work toward diagnosis.

Fourth: Seek a treatment for the sick bird.

Many diseases present with the same vague symptoms. For example, approximately nine respiratory diseases start with a cough, wheezing, droopiness, a pale head, and facial swelling. No friend, veterinarian, or poultry professional can diagnose over the phone or Internet (and to do so is fraught with possibilities of error and litigation). A personal examination of the bird, followed by detailed testing, is the best way to obtain an accurate diagnosis.

Examining Your Birds

Getting to know your birds is the best assurance that you’ll be aware when something’s not right. Handle your birds frequently so you become accustomed to their sizes and weights. After doing so on a monthly basis, you’ll have a better chance of detecting irregularities in the weight or overall health of your flock members.

If you detect illness, do a quick management assessment. Answer questions such as the following. Also, work with an extension agent to make sure you’re making the right queries.

![]() Have you recently switched feeds?

Have you recently switched feeds?

![]() Have you introduced new birds recently?

Have you introduced new birds recently?

![]() Has the coop temperature recently dropped or increased?

Has the coop temperature recently dropped or increased?

Next, examine droppings in the coop or around the sick bird:

![]() Do they look different than your flock’s “normal”?

Do they look different than your flock’s “normal”?

![]() Is there blood in the droppings?

Is there blood in the droppings?

![]() Do the droppings look particularly green (which means the bird isn’t eating a balanced diet) or another color?

Do the droppings look particularly green (which means the bird isn’t eating a balanced diet) or another color?

![]() Are there undigested food pieces or worms in the feces?

Are there undigested food pieces or worms in the feces?

You may notice that early in the morning, your birds’ feces look green. That’s normal. You’re seeing bile from the gallbladder. Birds that have not eaten recently continue releasing bile into the digestive tract. It’s not normal for a chicken’s feces to stay green all day long for days at a time.

Examining your birds will make you accustomed to their individual qualities, making it easier to know when they may be ill.

The feces of a bird not eating much may look green all day (versus the brown color of a bird eating normally). Check the mouth of a bird with green feces for an obstruction or lesion that may prevent normal feeding. If you are unsure whether a bird is eating a healthy amount, feel its crop at night, after the flock has gone to roost, to see whether it is full.

Use all five senses when examining your birds. Try these tricks:

![]() Examine sick birds for signs of injury. Perhaps a disease agent is not to blame, but rather a bullying, dominant bird. Part the feathers to search for wounds. Watch the behavior of your flock.

Examine sick birds for signs of injury. Perhaps a disease agent is not to blame, but rather a bullying, dominant bird. Part the feathers to search for wounds. Watch the behavior of your flock.

![]() Listen to your birds’ breathing patterns. Any sign of wheezing, coughing, or gasping indicates respiratory distress. If a bird exhibits these symptoms, look for swelling around its eyes. Unlike humans, chickens have skin directly over their sinuses so an infection causes swelling of the face, particularly around the eyes. If the swelling becomes too severe, the bird can even have difficulty blinking.

Listen to your birds’ breathing patterns. Any sign of wheezing, coughing, or gasping indicates respiratory distress. If a bird exhibits these symptoms, look for swelling around its eyes. Unlike humans, chickens have skin directly over their sinuses so an infection causes swelling of the face, particularly around the eyes. If the swelling becomes too severe, the bird can even have difficulty blinking.

![]() Check your birds’ feathers. Are they brittle or curled if they shouldn’t be? These both indicate insufficient protein in the diet.

Check your birds’ feathers. Are they brittle or curled if they shouldn’t be? These both indicate insufficient protein in the diet.

![]() Pay attention to muscle movement and balance. Does the bird have difficulty maintaining balance? This can point to nervous system difficulties. If a bird limps, examine the bottom of its feet for signs of injury. In wet litter, ammonia burns—black, scab-like blisters—can appear in the center of the foot or on the hock (the part of the leg where the feather meets the scale). You may also spot an injury called bumblefoot, which occurs when a sharp object pokes the foot pad and causes an infection in the foot.

Pay attention to muscle movement and balance. Does the bird have difficulty maintaining balance? This can point to nervous system difficulties. If a bird limps, examine the bottom of its feet for signs of injury. In wet litter, ammonia burns—black, scab-like blisters—can appear in the center of the foot or on the hock (the part of the leg where the feather meets the scale). You may also spot an injury called bumblefoot, which occurs when a sharp object pokes the foot pad and causes an infection in the foot.

Getting an Accurate Diagnosis

How can you advocate for your flock given all these potential dangers? Getting to know your birds is a great—and crucial—start. After that, you have more options than you think.

First, establish a relationship with a veterinarian who sees birds or exotics. This may mean driving an extra hour or two for an appointment, but consider it as an essential part of the challenge of raising poultry. If the only available option is your regular or livestock veterinarian, be aware that many will say off the bat that they do not work with poultry. Ask the vet to call a nearby extension poultry veterinarian, a person who offers phone consultation services for treating chickens.

Do your homework in advance so you have contact information ready for the nearest one. To find the appropriate extension poultry veterinarian, call your local cooperative extension office (every county in the United States has one, and universities in each Canadian province have associated agricultural extensions) or search for one online using terms such as cooperative extension and your county or town name. Your dog or cat’s vet can also get assistance from your county’s extension office to contact a poultry vet.

Even with these resources, you may not get an instant diagnosis for your sick chicken. However, these specialists can recommend additional tests, the type of which you will help determine by your description of the chicken’s symptoms. When this happens, your regular vet may need to send blood samples, fecal samples, or throat swabs to the nearest diagnostic laboratory. Some labs provide services free to owners of small flocks; others charge a nominal fee.

Administering an eye-drop vaccination

Vaccinations versus Antibiotics

With accurate diagnosis in hand, you can plan your attack on the disease agent. There is a difference between giving antibiotics and vaccinations. Vaccinations most often fight against viruses and with the exception of Layrngotracheitis, must be given prior to exposure to that virus. Just as in humans, this process allows the chicken to develop the appropriate antibodies and may provide the ability to fend off the virus.

Vaccinations are never a one-time deal. Just as humans require multiple doses of certain vaccines, so do chickens. To prime their immune systems, they receive mild forms of vaccines when they are young. Work with your vet to determine what you need to vaccinate for in your region of the country or the world. Once primed, the chickens get an annual shot of vaccine to ensure coverage for the year. Think of it like the annual flu vaccine for humans.

Antibiotics attack bacteria. They are short-lived and must remain in the body for several days to effectively fight the majority of invading bacteria. Antibiotics cannot defeat a virus and if given for an insufficient amount of time, may cause the bacteria to build up resistance rather than die. Once the immune system is down, any bacteria, including an antibiotic-resistant strain, can cause a serious secondary infection, which can lead to death. Throwing antibiotics at a flock wastes money and may cause antibiotic-resistant bacteria to proliferate. Now that the Veterinary Feed Directive will take many over-the-counter antibiotics off the market, you will need to obtain a veterinarian’s prescription to get them. Confirm an accurate diagnosis by using a veterinarian or your state diagnostic lab before administering antibiotics to your flock.

COMMON DISEASE ENEMIES

You’ve learned how to examine your flock and where to go for diagnoses. Now it’s time to arm you with information about some enemies of a healthy flock. In the rest of this chapter, we discuss several common poultry ailments, along with treatments and preventative measures. These are not the only poultry diseases. Be sure to seek an accurate diagnosis from a veterinarian or poultry diagnostician before beginning any treatment regimen.

Note: Many different diseases out there affect chickens and other poultry species. For example, one organism may be able to infect chickens and pheasants, while another may only cause illness in turkeys. Poultry germs come in the form of viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Additionally, an arsenal of parasites out there can colonize a bird both externally and internally. For the purposes of this book, we focus on the most common diseases chickens can get.

Marek’s Disease

This incurable virus attacks a bird’s nervous system, causing perisis or partial paralysis, such that at one time, it was known as range paralysis. This partial paralysis can be seen when one side of the body (wings or legs) suddenly exhibits poor motor control. Occasionally one leg will stretch out forward while the other goes backwards. The virus can also cause tumors and tremors, as well as immuno-suppression, opening up affected birds to infection by everyday germs. It typically strikes birds less than sixteen weeks old.

The virus spreads directly from bird to bird, but also through contaminated equipment, dust, bedding, down, and bird dander (the small flakes of feather follicle shed as a bird grows new feathers). It has an unusually long incubation period where a bird sheds virus and remains contagious for two weeks before showing any clinical signs of disease. The virus also resists many disinfectants.

The best prevention is to vaccinate one-day-old chicks, no older. In commercial broilers or layer hatcheries, chicks are vaccinated inside the shell at day eighteen of embryo development to ensure that they hatch with antibodies to the virus. If buying your chicks at one of these hatcheries, order chicks already vaccinated against Marek’s disease. If you choose to hatch eggs at home or let a setting hen do the work of an incubator, keep several bottles of Marek’s disease vaccine on hand. Mix a fresh batch for each set of hatched chicks (the vaccine is only viable for a few hours after being mixed). Vaccinate chicks within their first twenty-four hours. Even just forty-eight hours post-hatch, their immune system has changed and they rapidly become less receptive to the vaccine.

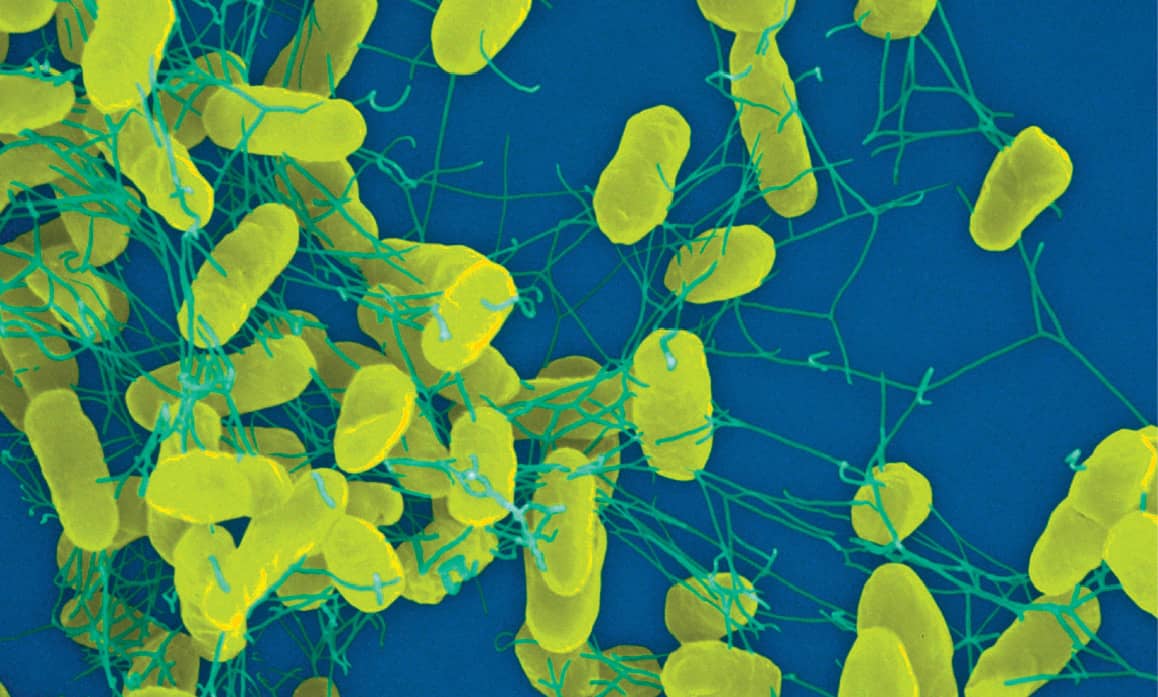

Salmonella

The bacteria Salmonella is capable of colonizing many different animal species and environments. With that in mind, understand that they fall into two broad categories when it comes to poultry: Salmonella that colonize and cause illness in chickens only and Salmonella that colonize and cause illness in humans through chickens.

Many years ago, chicks being shipped post-hatch would die in transit or shortly thereafter due to the first type of Salmonella. This led to the creation of the (U.S.) National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP), which tests and then removes breeding adult birds that carry this form of the bacteria. If you plan to purchase chicks in the United States, always buy them from an NPIP-approved hatchery; these places take steps to ensure that chicks arrive at your door pullorum- and typhoid-free.

The second form of Salmonella infects humans through poultry and eggs, Salmonella Enteritidis (SE).

In the past several decades, SE has caused great concern due to multiple outbreaks in contaminated eggs. The hen lays eggs containing these bacteria. The bacteria then infect the human who eats the eggs raw or undercooked. That’s why health experts always recommended fully cooking foods that contain eggs as an ingredient. If you’re a flock owner who gives away, barters, or sells your extra eggs, keep in mind this recommendation about eggs being fully cooked before eating.

Your best bet to prevent infection by these bacteria—which can be present in your flock without birds showing any signs—is to use excellent biosecurity measures such as those we discussed earlier in this chapter and to fully cook your eggs to prevent food-borne illness. Probiotics—live organisms fed to the birds to outcompete bad bacteria—may be an option for your poultry. If you find that your birds carry Salmonella, you may wish to give them antibiotics prescribed by a veterinarian who will oversee dosages and duration of these antibiotics.

For more information on Salmonella, see here.

Salmonella

Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma take several weeks to grow in the lab before it’s possible to make a definitive diagnosis. They are responsible for a series of respiratory symptoms known as chronic respiratory disease or CRD. The strains most often associated with illness in poultry are Mycoplasma Gallisepticum (MG), Mycoplasma Synoviae (MS), and Mycoplasma Meleagridis (MM).

Wherever you may purchase chicks, we recommend you ask hatcheries if they carry NPIP certification proving that their chicks are also free from MG, MS, and MM. Don’t let the hatcheries tell you that Mycoplasma are problematic only in turkeys; this is not true.

Many owners of small flocks believe that it’s normal for chickens to get a common cold in the fall, winter, or spring. It’s not. Most frequently, cold-like symptoms result from an infection caused by Mycoplasma and poor biosecurity. Mycoplasma bacteria spread slowly through a flock, causing drops in egg production, an increase in thin-shelled or irregularly shaped eggs, or both. These infections are well known for their ability to strike laying hens with great frequency. There is a six- to twenty one–day incubation period for these bacteria to begin causing respiratory symptoms, as well as weight loss and swelling of the eyes. (Note: These symptoms also indicate several other respiratory diseases, so be sure to obtain a clear diagnosis.)

Prevention, made possible by solid biosecurity, is key with MG, MS, or MM. Vaccination also can help prevent an outbreak. Purchase vaccine from manufacturers directly or in smaller quantities from veterinary supply companies. You can buy and administer this vaccine yourself. However, for a specific vaccination schedule, consult with a veterinarian.

Coccidiosis

Coccidiosis or Cocci (pronounced cock-see) is an internal parasite of chickens. It is a protozoan rather than a virus or bacterium. Nine different coccidia infect chickens, though these coccidia cannot infect other animal species.

Chickens get coccidia through coprophagy, or eating feces. They eat their own, as well as that of other chickens, poultry, and wild birds. This is normal behavior. Once the coccidia get inside a chicken, they hatch, burrow into the intestinal lining, breed, and send new eggs into the world through the bird's feces. If one chicken gets coccidia from infected feces, the parasite infects the ground of the coop. It can spread from bird to bird. Coccidia survive in the coop through damp ground, litter, or unsanitary living/brooding conditions. This tends to hit chickens early, at about three to six weeks old, with the illness occurring most frequently at about one month of age. Chickens with coccidia may grow to adulthood and lay eggs, but their overall performance may never equal that of an uninfected bird.

The first symptom of Coccidiosis is a red or orange tint to the feces, either in lumps or in slick dropping from diarrhea. These colored lumps indicate damage to and bleeding from the gut lining as the coccidia burrow in. Soon bacteria gain entry to the bird's bloodstream and other tissues, causing a secondary infection. Feed consumption drops and birds become droopy, withdrawn, and pale.

You have two choices at this point: medicate or let the disease run its course with the potential for some chickens to die. If you opt for the latter, birds that survive infection by one coccidia strain are not immune to the other strains. Before medicating, get an accurate diagnosis by having a regular vet perform a fecal flotation test on fresh droppings from an affected bird.

Once you identify that coccidia are to blame, work with your veterinarian to determine the most effective dosage of coccidiostat.

Once again, prevention is key to keeping this disease out of your flock.

![]() Change bedding often, particularly once it gets damp.

Change bedding often, particularly once it gets damp.

![]() Do not overcrowd your chicks.

Do not overcrowd your chicks.

![]() Make sure you clean the brooder between sets of chicks. Your best bet is to raise your chicks on wire in a commercial-style brooder (see chapter 6 about brooders for a picture) to separate them from their feces.

Make sure you clean the brooder between sets of chicks. Your best bet is to raise your chicks on wire in a commercial-style brooder (see chapter 6 about brooders for a picture) to separate them from their feces.

You also can buy chicks from hatcheries that vaccinate for Coccidiosis. Contact your nearest veterinarian or extension agent for assistance if an outbreak of coccidia is confirmed.

Aspergillosis

Aspergillosis is caused by a fungus and can be especially damaging to chicks. Chicks have new cilia in their respiratory systems that do not operate perfectly until they are much older and therefore cannot fight off a rapidly moving fungal infection. Chicks show respiratory symptoms such as open-mouthed breathing or gasping for air. Also, infected chicks or adults may appear to have problems with their nervous system in the form of tremors, an inability to keep their balance, or even twisting their head around. This may be due to fungus growing in the brain or other tissues in the nervous system. Although this fungus can kill chicks, it may become a chronic problem in adult birds.

Aspergillosis

Airborne spores spread the fungus in warm, moist, and dirty environments. This occurs most often in an unclean incubator or brooder for chicks, but adult birds may become infected if the chicken coop is not kept clean. Eggs that come in to the incubator dirty may carry the spores from the fungus. Make sure that the eggs are laid in clean nest boxes. We do not recommend filling nest boxes with straw as it may carry the fungus.

Diagnosis usually comes by microscopic identification of the fungus found in infected internal organs such as the air sacs, lungs, or trachea. Symptoms of this disease look similar to Marek’s disease. Regular cleaning reduces the presence of the fungus. Also, the addition of copper sulfate to the water helps prevent spreading the fungus through the flock. Drugs such as Nystatin and Amphotericin B are expensive but work to treat sick birds. Humans with suppressed immune systems can develop a similar form of pneumonia (mycotic pneumonia) caused by the fungus. Here's the fundamental message: Keep it clean!

Parasites

EXTERNAL PARASITES

External parasites most often come in the form of mites (chicken, northern fowl, and scaly-leg) and lice (chicken body and shaft). These parasites can actually suck the blood of the bird, irritating the animal day and night, preventing it from getting the restorative sleep it needs. This weakens the chicken’s immune system, thereby opening up the bird to other diseases.

Check your birds weekly or monthly for signs of external parasites. To do so, part the chicken’s feathers above and below the vent and look directly at the skin. Only scaly-leg mites are microscopic, so you will be able to see the others. Also look at the bird’s feathers. Are they see-through or have lost their sheen? Do they have striations? These could indicate external parasites.

If your birds have external parasites, prepare for a long battle. You will not only need to treat the birds for several months, but you also will need to fully clean out the coop and spray it with the appropriate insecticide. Winter is when birds crowd together for warmth. Therefore, this is also when to increase your vigilance against external parasites.

Chicken Mites

Also called red mites, these parasites hide in the coop’s nooks and crannies during the day and feed on birds at night. The chicken mite has been known to live in an environment for up to thirty-four weeks without anything to feed on. If they appear in your coop, make sure you thoroughly treat the chickens and clean the environment. To check for chicken mites, go to the coop after dark with a flashlight in hand. Lift the feathers on your birds’ legs where the scales meet the feathers. Look for tiny red (after a meal of blood) or gray bugs. They do not move quickly and may even freeze at the sight of light.

Chicken mite

Treat the birds and the entire coop to rid your flock of this problematic parasite. To start, wash the chickens weekly with a mild soap. You also can dust the birds with poultry dust (a chemical insecticide) or other carbaryl-based dust such as Sevin. This is time-consuming and you should make sure to wear a mask so you don’t breathe in the dust. Other options are PERMECTRIN II 10 percent solutions that come in concentrated form that you must dilute before spraying on chickens or in the coop. This type of insecticidal spray is quite effective and can be purchased at most feed stores. One bottle can last the owner of a small flock several years. Always mix these according to the directions on the label. And remember, treat the environment and the birds.

Northern Fowl Mites

These parasites are another type of mite that can harm your flock. They are brownish-gray and about the same size as the chicken mite, but spend their entire life cycle on the bird. Check your birds near their vents, particularly below the vent in the thicker feathers, for something that looks similar to dirt (but, of course, dirt doesn’t move). Northern fowl mites also leave behind feces that look like the flea dirt seen on dogs or cats. Some other signs of this parasite are: whitish egg clusters at the base of the feathers, scarring, or red inflamed skin.

This is a mite that in some cases may come into your coop via wild birds, so minimize your flock’s contact with this potential hazard. If you spot northern fowl mites, use the same treatments and regimen for the birds and the coop as described for the chicken mite. Again, washing the chickens can work, but remember to treat the environment, too. Remove any contact with wild birds to prevent re-infestation.

Northern fowl mite

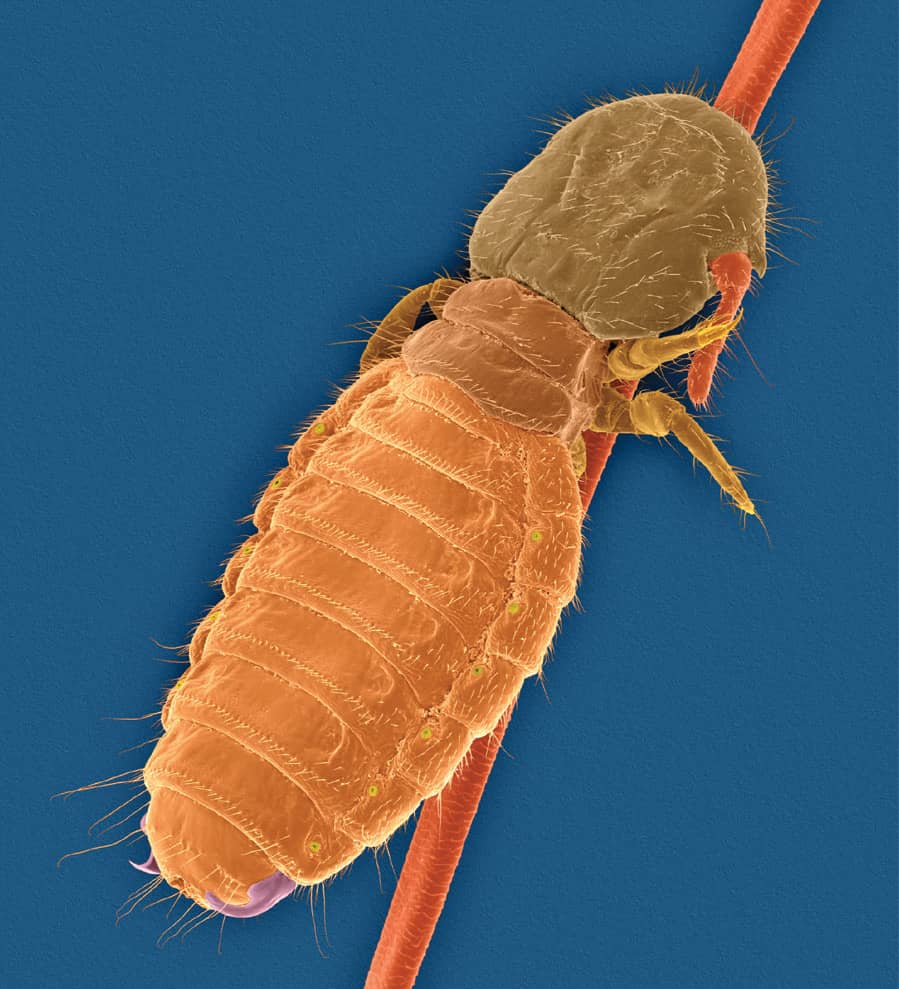

Chicken Body Louse

Chicken body lice are each half the size of a grain of rice and run very quickly. Their life cycle is short, so they reproduce quickly—meaning high numbers in short periods of time. They are light tan and most often appear around a chicken’s vent. Part the feathers quickly and look down on the skin; the lice run for cover so be sure to check three or four places around the vent, under the wings, on the back, and on the breast. Also, look for clumps of whitish eggs glued to the feather fluff, very similar to the northern fowl mite.

Chicken body lice can come to your flock via wild birds, so protect against this hazard. Louse can enter your flock by a newly introduced hen. Check for parasites during the quarantine period. Treat the birds twice in a ten-day period—once on day five and again on day ten—to ensure that you kill not only the adults, but also any young lice that hatched once the insecticide levels subsided. Once again, washing the chickens is a solution, but you also must clean the environment.

Chicken body louse

Shaft Louse

Shaft lice are harder to see. Darker in color and often found along a feather’s main shaft, they tend not to move once the feathers are disturbed. They move slowly and lay eggs individually along the shaft of the feather. Sometimes on the primary and secondary wing feathers, you may see dark flecks that could be shaft lice. To check, pluck a feather (preferably not a primary or secondary wing feather) that contains a suspected louse and poke at the spot with a pin. After several prods, the louse may move on its own in an effort to relocate. Much like the other mites and lice described, these come to your flock through contact with wild birds. Similar treatments apply.

Shaft louse

Scaly-Leg Mite

This is a very different type of mite. It is microscopic, usually identified by the damage it does to any keratinized surface on a chicken (leg scales, shank scales, and beaks). The mite burrows through the surface to reach the skin’s blood layer. It then multiplies, deforming the scales, which take on a flaky, crusty, irregular appearance. Soon large lumps appear on the legs; these can eventually cripple the bird. If left untreated, the beak may fall off or become permanently damaged.

To treat this ailment, suffocate the mites with an oil-based product. For at least two weeks, cover the chicken’s legs daily in petroleum jelly, a camphor oil, or a half-kerosene, half-cooking oil mix. You may wish to wash the legs nightly in warm, soapy water to soften the scales. Gentle scraping also helps loosen and remove dead scales and mites. Continue this regimen until the legs return to their normal appearance.

INTERNAL PARASITES

These parasites come in the form of roundworms or tapeworms. There are several types of roundworms that can affect chickens, including cecal worm and gapeworm. These breed in a chicken’s gut and rob the bird of crucial nutrients. Roundworms can be treated using the one over-the-counter wormer on the market. Do not worm without verifying that your chickens actually have worms. Do this by looking at chicken feces for adult worms. You may not always be able to see adult worms, so take a sample of fresh feces to your nearest veterinarian to perform a fecal flotation test (as described in the Coccidiosis section). Roundworm eggs are small and can only be seen through a microscope. Adult roundworms are 1- to 11/2-inches (2.5 to 4 cm) long and quite thin. To prevent reinfestation after treatment, clean out the bedding in the pen where the deworming treatment took place.

Tapeworms release their eggs in packets that can sometimes be seen moving in the feces. Once dried, these packets—about the size of a rice grain—open, spreading out the eggs. A tapeworm infestation can cause serious damage to the birds, feeding off their blood supply and stealing their nutrients, and unfortunately, they cannot be eliminated using the over-the-counter wormer described above. In fact, there are no over-the-counter tapeworm wormers suggested for use in poultry, so you need to seek a diagnosis, treatment, and prescription from a veterinarian.

Even if your birds don’t exhibit symptoms of a worm infestation, for example, they’re eating normally but losing weight, check their feces twice a year using the same fecal flotation test mentioned in the Coccidiosis section. This time, look for worm eggs. This is particularly important if you allow your birds access to the outdoors.

Avian Influenza and Newcastle Disease

You may have heard of the bad boys in the world of avian respiratory disease. Their names are avian influenza (AI) and Newcastle Disease (ND). Avian influenza made the news several years ago when an Asian strain of the virus began to infect humans. More recently, avian influenza caused the deaths of millions of chickens and turkeys in the Midwest. Symptoms of these viruses in chickens include coughing, sneezing, watery eyes, mucous, and any sort of respiratory symptoms.

AI and ND are game enders in the world of raising poultry. Detection of either disease typically causes a halt to the sale of poultry products from the country that is infected, resulting in economic distress for world poultry markets and poultry companies in that country. Keep your birds healthy and free of respiratory diseases, if not for the health of your home flock, then for the sake of all chicken owners.

If your chickens contracted a virulent form of AI or ND, the entire flock could be wiped out by the virus in two or three days. Any birds that lived would get tested and then tested again to rule out any false positives. At this point, someone from the government would likely have contacted you to ask you to avoid contact with other birds and to implement your most secure biosecurity measures. This is to keep whatever is on your farm on your farm and prevent it from infecting neighboring flocks. That means no birds wandering outside and no unnecessary travel for you to places where you could encounter other flock owners (for example, the vet’s office, a feed store, a poultry club meeting, etc.). Consider yourself quarantined until you sort everything out.

If your birds come down with a virulent form of one of these diseases, they likely need to be put down. It’s the humane way to act, as they are likely suffering greatly. If dealing with a milder form of either disease, you unfortunately may still need to put down the birds, as they can spread the virus to others or it can spontaneously become more virulent. If one of these diseases comes up, get help and fast so you can humanely euthanize flock members in serious distress.

Poultry fallen victim to avian flu

NONINFECTIOUS AILMENTS

You now know about infectious diseases that affect chickens. Let’s turn to other noninfectious poultry health problems. These ailments, which typically surface from problems in management or housing, often get cured or can be prevented with simple changes to the coop or bird care.

Bumble Foot

Bumble foot is a foot infection that makes a bird limp or feel uncomfortable. It typically occurs because the bird has stepped on something sharp.

As soon as you see one of your chickens limping, look at its feet, specifically seeking out scars or scabs in the center of the three large toes. The center of the foot may also feel hot and appear swollen. If not caught early, this limp may become permanent, or infection could become systemic and the bird could die. If you can see the scab, one option is to use your fingers to push out and squeeze the puss and scar tissue building up in the wound. If you choose to perform this procedure on the bird, wash the wound, wrap the foot in gauze immediately, and then during recovery, place the bird in a sick pen that contains a great deal of deep bedding. Rinse the bird’s wound daily with a warm soap that contains iodine, apply a wound spray, and then rewrap the foot. Also pay attention to the sick bed, cleaning it daily to remove feces or wet bedding. You’ll know the bird has recovered when it starts walking normally again. Some physical therapy will help keep both legs strong during recovery.

Remember to look for the source of the injury, so it won’t harm other chickens. Touch all surfaces of the coop with your bare hands, feeling for something sharp. Remove the culprit or make repairs where necessary.

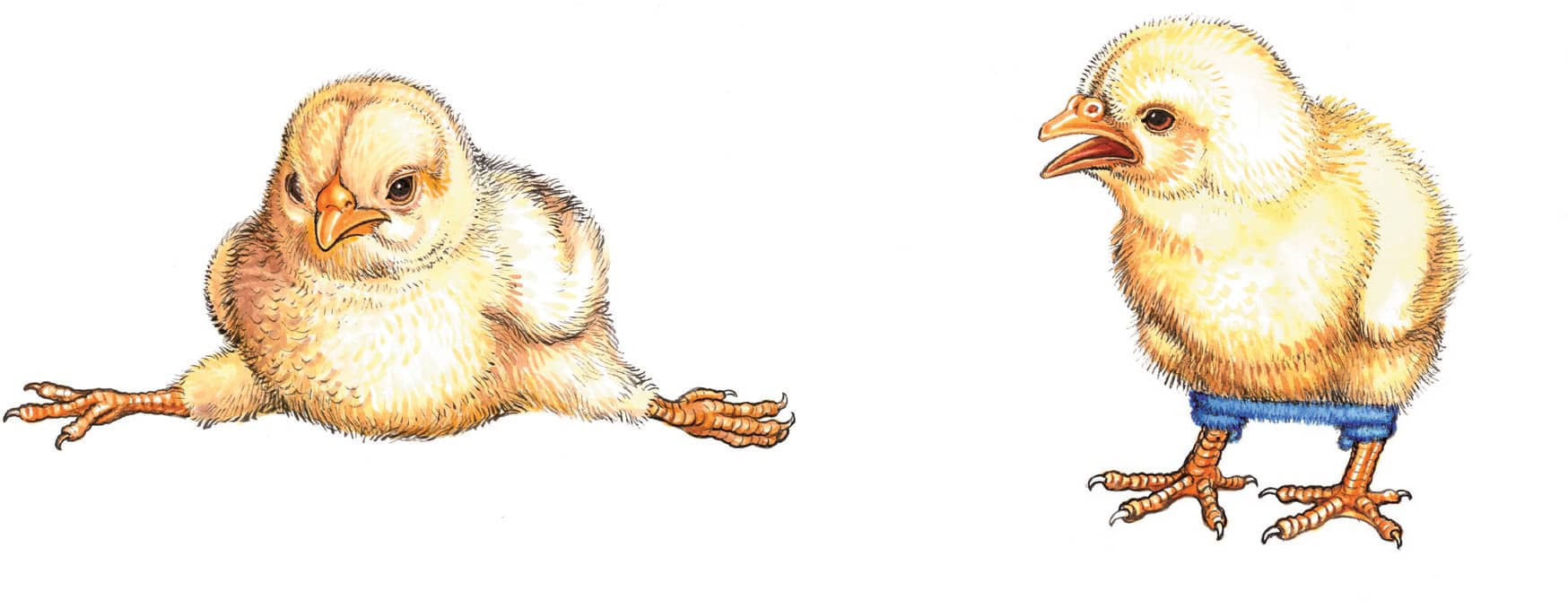

Spraddle leg and correcting spraddle leg at home

Spraddle Leg

Spraddle leg, which typically occurs during brooding, is just as it sounds: A slick surface causes a chick’s legs to spread out in opposite directions, to the left and right, causing slipped tendons. The condition is painful for the chick and can cause permanent damage to the legs, eventually preventing the chick from being able to walk. Sadly, the baby bird will eventually starve and die because it cannot reach food or water.

You can fix spraddle leg if you identify it early. Create a small splint using a pipe cleaner or plastic bandages. If using a pipe cleaner, cut off a 3-inch (8 cm) piece and gently wrap one end around one leg. Lightly pull the other leg into a normal position, and then wrap the other pipe cleaner end around the other leg. Most chick owners splint the chick themselves rather than going to a vet.

To prevent spraddle leg, avoid using newspaper or magazines in your brooder as flooring; they are too slick. Instead try wood shavings, wire, or even a nubby old terrycloth towel. (Look back to chapter 6 for a refresher on brooders.)

Curled Toes

Newly hatched chicks with this condition cannot unfurl their toes and therefore cannot walk normally. This can occur because of poor genetics or the breeding adults’ diet. It also can come from errors in temperature or humidity during incubation. If not corrected, this can lead to sores on the chick’s hock and breast and eventually starvation because the chick can't walk properly.

Fix the problem by uncurling the toes and taping them into the correct position. Use a small piece of heavy paper and tiny strips of masking tape to arrange the toes into the correct position. You can also try plastic bandages. Uncurl the toes, place them in the correct positions in the bandage’s center, and then wrap the adhesive ends over the top of the toes to hold them in place. Be sure to trim any excess material. You’ll need to change these dressings daily because chicks grow rapidly—even in a few days’ time.

Curled toes and correcting curled toes at home

Frostbite

Frostbite often occurs on a bird’s comb, wattles, and toes, potentially causing these features to turn yellow or black. This dead tissue may fall off over time.

Breeds with large, pendulous wattles get these appendages wet every time they drink. Also, the comb of some chickens becomes so large that it’s unable to fit entirely under the bird’s wing at night. And incorrectly sized roosting poles—too small or too large in diameter—can prevent the birds from pulling their breast feathers over their toes at night for warmth.

Solve this winter problem by keeping the coop at temperatures above freezing. Also, use a heated water base to keep the chickens’ water above freezing. Finally, at night before the birds roost, try spreading a small amount of petroleum jelly over the combs and wattles of birds with large combs. However, note that this gets messy quickly because the jelly spreads on to the feathers. Messy feathers pick up dirt, so you’ll need to wash these birds periodically. If temperatures dip too low, even the petroleum jelly may freeze, so your best bet is a warm coop.

Chickens can develop frostbite on their extremities if exposed to extreme cold temperatures for an extended period.

Egg Bound

Egg-bound hens experience difficulty passing an egg normally. Whether a chronic problem or a singular event, being egg bound is a dire situation for the hen. These birds take on a penguinlike stance and their abdomens get hot. They also appear strained. Depending on the hen and the situation, the egg may eventually pass. However, sometimes the egg gets caught in the hen permanently, which may eventually result in death. Also, if the egg breaks inside the hen, she will die.

Try to help the hen by immersing her vent and backside in warm water, then very gently massage the area around the egg. Be gentle when handling the hen’s abdomen and careful around the egg or it may break. Another option entails putting a small amount of mineral oil on a latex glove and gently massaging the oil up the chicken’s vent and into her oviduct to aid the egg’s exit. If the hen’s quality of life is no longer sufficient, you may consider culling her.

Never breed egg-bound hens because the problem can be genetic.

Internal Layer

An internal layer is a hen that passes her yolks not into the oviduct (the correct place), but rather into her abdominal cavity. Older hens with less efficient reproductive tracts may become internal layers. You can tell this is going on if the abdomen becomes hot or distended, indicating an abdominal infection. Sadly, there is nothing that you can do for these hens, as they often pass yolks into their abdominal cavities daily. Most internal layers die.

Prolapsed Vent

A prolapsed vent—when the oviduct has been pushed out of the body as the hen tries to lay eggs—often occurs in young birds. The eggs may be too large for the not-fully-developed oviduct. In other words, if a hen is exposed to too much light before her reproductive tract matures, she will try to lay eggs before her body is completely ready. Light-bodied hens such as Leghorns should start laying at about sixteen to eighteen weeks. Heavy hens, such as most hybrid brown-egg layers, begin around eighteen to twenty weeks.

If you find a hen with a prolapsed oviduct, separate her from the rest of the flock immediately. The oviduct will be shiny and attractive to other chickens, which may come over and peck at it. This type of cannabilism can quickly kill the affected hen. Thoroughly wash off the prolapsed oviduct and then wash your own hands. Using a glove and mineral oil, push the oviduct back in through the vent. Once a hen prolapses, she is prone to doing so again, so keep her separate in the sick pen for several days as her body matures and heals.