Chapter 5

PROGRAMMING AND IMPLEMENTING YOUR STRATEGY

The right strategy is never more than 49 percent of the problem.

—Joseph Bower

A new strategy must first be programmed • Future-oriented activities and the role of the senior team • Minimally viable bureaucracy • The master plan • Breakthrough innovation teams • Incubator designs • A discovery-driven approach • Implementation—incubating, accelerating, and transitioning • There is always more future ahead of us

A few years ago, we worked through our future-back process with the leadership team of a midsized manufacturing company. The future state portfolio we developed together was focused on achieving much greater profitability than its commoditizing core businesses could deliver, and the strategic path we laid out to achieve its aims was clearly defined. But when we suggested to our client that it was time to step back and carefully consider how each of their new initiatives should be governed, organized, funded, and implemented, they demurred.

“Execution is what we do,” they argued. “We know how to manage the work.”

A year later, we got a call from the CEO, who was frustrated that the strategy hadn’t gained enough traction; progress was much harder and slower than he’d ever imagined. We reminded him that while execution within the core business might be an area of consummate strength for his firm, the implementation of a transformative, long-term strategy requires a different set of processes and overall capabilities.

Their situation was not unique. A survey of nearly two thousand executives conducted in 2015 found that only 26 percent had faith that their company’s transformative strategies would succeed.1 Much of their pessimism, no doubt, can be ascribed to their companies’ past failures to develop a compelling vision and commit to the right strategies to achieve it. But just as significant is the fact that most organizations leap reflexively from strategy to execution, using the structures, processes, rules, and norms that guide the execution of their core businesses to carry out their outside-the-core initiatives, which inevitably constrains or distorts their intended outcomes.

Just as a vision needs to be translated into a strategy, a strategy must be carefully programmed into an organization before it can be effectively implemented.

That is what William Hait did with the World Without Disease initiative. First, he recruited Ben Wiegand, a Johnson & Johnson R&D executive with extensive experience managing innovation, to build and lead a new group to pursue its portfolio of projects. Then they set up a small, purpose-built organization designed to move fast in an uncertain, risky environment, with a streamlined governance model that allowed for rapid decision making.

They focused on a set of disease areas that were the ripest for the new paradigm and that had the most realistic chances of becoming medically and financially significant in a relevant timeframe. One of them was lung cancer. Years of exposure to carcinogens from smoking or environmental pollution damages the lungs, leading to premalignancies that can theoretically be treated if they are detected in time. A second targeted colorectal cancer, as discussed in chapter 3. The third addressed type-1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease that most often strikes young children, disabling the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, forcing a lifetime of dependence on insulin injections. Emerging research has identified an escalating series of indicators, traceable in blood samples, that signal when a child is on the path to developing insulin dependence, opening windows for early interception.

Keeping their future state goals closely in mind, Wiegand’s group launched a slate of ventures. Each was led by an expert in the targeted disease area and tapped into broad networks of support. Each would be funded through its next milestone and then either shut down or escalated depending on its results. The idea was to strike fast (relatively, that is—biopharma development timelines are typically ten-plus years) in order to prove out the model. Some of these projects leveraged existing assets that could be accelerated; others focused on external investments and partnerships that were already making progress and could be brought in-house if their efforts succeeded. In an interview, Wiegand noted:

The key for us was to break our highly aspirational vision down into achievable milestones that we could easily communicate. We walked the vision back from ten years out to the handful of things we needed to accomplish by the end of the year to know we’re moving in the right direction at the right pace—always showing management how our initial milestones ladder up to the vision.

In the first year it was all about picking our top few focus areas, hiring world class leaders in each, and launching what we call “killer experiments.” We could get management aligned to these, and then demonstrate our success in a very real and tangible way.2

Achieving results, scaling programs that were working, and quickly shutting down programs that weren’t increased management’s belief in the team, unlocking additional support.

Step 1: Programming Your Strategy

Intentional approaches to setting up and managing a portfolio of new growth activities are essential for almost every visionary strategy. Corporations allocate resources, govern lines of business, and manage performance through management systems. Point solutions will inevitably get swallowed up by the existing system, which is already deeply entrenched. Systems-level challenges demand systems-level responses.

When programming a breakthrough strategy, you must design and assemble a set of components that ultimately come together as an integrated system. Critically, those components must:

- Formalize the roles and responsibilities of the senior leadership team as champions of both the strategy and the breakthrough innovation teams set up to carry it out

- Set up an organizational model that protects breakthrough innovation teams from the countervailing influences of the core

- Manage initiatives with an explore, envision, and discover process so senior teams and innovation teams can learn their way to success together

We will describe the key elements of such a system in this chapter, but every company’s circumstances are unique. Put another way, we can give you the key ingredients, but finding the right recipe is the work of you and your team.

The Roles—and Responsibilities—of the Senior Leadership Team

Senior leaders must be actively engaged in all the big decisions that determine a breakthrough effort’s success or failure, championing the new strategy while leaning in to help the innovation team problem-solve when necessary. The ultimate responsibility for future-oriented initiatives cannot be delegated; that’s why Ron Shaich, the founder and former CEO of the restaurant chains Au Bon Pain and Panera Bread liked to call himself the “discoverer in chief.” “I think there are two big parts to any business, discovery and delivery,” he told Inc. magazine. “One of my most powerful roles as CEO is to protect discovery.… My job,” he added, “is to get this company ready for the future.”3

Doing that well requires a substantial commitment of time. A. G. Lafley of Procter & Gamble told us he would sit down monthly with his head of R&D and, “depending on the innovations or technologies involved, the right players from the functions, P&G Ventures, and in some cases, the businesses. Then we would review the technologies, new products, and business model innovations we were developing and testing. The main point here,” he added, is that “the CEO is de facto the CIO/Chief Innovation Officer in any company where innovation is a critical strategy to drive growth and value creation.”4

The leaders of Boeing’s Horizon X and Boeing NeXt innovation organizations meet monthly with Boeing’s CEO, CFO, and Chief Technology Officer. As Boeing NeXt VP and general manager Steve Nordlund told us at an annual Innosight CEO Summit, “We don’t present charts at these meetings. We have dialogue; we talk and pivot and learn.”5

Governance

The first job of the senior leadership team is to design a governance system that will allow them to manage the implementation of the strategy as efficiently as possible, given all the competing demands on their time and attention.

It’s best to aim for a minimally viable bureaucracy. Though you should establish clear rules for getting approvals, which will help avoid chaos and ensure adherence to the strategy, too much process bogs things down. Importantly, you should ensure that the breakthrough innovation teams report directly to senior leadership and retain autonomy from the core business. Without this separation, disputes will inevitably arise. If senior leaders don’t support the innovation teams, the core business will always win, sapping the new initiatives of their unique attributes and hence their breakthrough potential. Though maintaining autonomy may be relatively easy in the early days, once a new venture starts to attain scale it will become more threatening to the core and the fortitude of your governance model will be tested.

Often the senior leaders we work with create a “New Growth Board” or “New Growth Council” to oversee new growth initiatives. These are made up of a subset of key senior leaders (for example, the CEO, CFO, head of strategy, head of business development, head of R&D, and an expert outsider). As a senior champion, each will likely spearhead or sponsor one or more strategic initiatives germane to their expertise and passions, much as the partners at venture firms serve on the boards of several portfolio companies.

Transformation Management Office

The new growth board oversees everything, but the day to day management of this work should be administered by what we often call the transformation management office (TMO), which is usually led by a senior executive (typically the chief strategy officer or the COO), and staffed by a small group of full-time employees who have deep knowledge of the organization and are able to think beyond its conventional approaches and habits. Like a program management office (PMO) within established businesses, the TMO ensures that new initiatives have the resources they need, coordinates support for outside-the-core efforts from functions in the core, and makes sure that key metrics are achieved and milestones are met on time.

Master Plan

The TMO organizes and oversees a master plan, a living document that organizes all of the major tasks or activities related to the implementation of the strategy in one place, serving as both a roadmap and a dashboard that helps determine whether it is on or off track. This picks up from the walk back in phase two, in which the future state is reverse-engineered into a set of initiatives in the innovation portfolio. Similar to any simple work plan, the master plan breaks those initiatives (both outside the core and within it) down into chartered workstreams, with clear objectives, scopes, activities, timelines, and resourcing, covering both budgets and people.

Funding

Funding for core initiatives is relatively straightforward, as they won’t require much in the way of new people, systems, and capabilities, and their business models are well understood. Funding for breakthrough initiatives should be ringfenced and protected at first (as specified in the investment portfolio), and then, as an initiative begins to mature, strictly metered to manage risk, ensuring that you’re not investing too much or too long in any given idea before you’re confident it’s on a path to success. As we’ve seen, each Janssen initiative was only funded through its next milestone and then either closed down or accelerated.

Very few people are willing to admit defeat, but with breakthrough innovation work, the likelihood is that many of your projects won’t ultimately succeed. Senior leaders should remind the teams that what did you learn? is as important a question as what did you achieve? As with venture capital, it’s a portfolio game; pivot ventures when they need to pivot, and shut them down and reallocate their capital when they aren’t panning out.

The Organizational Model for New Growth Innovation Teams

Before you get too far into the planning and execution of an initiative, you should bring in the people who will own it going forward. Look for a leader, like Janssen’s Ben Wiegand, who has relevant domain expertise, general management skills, and entrepreneurial ability—the equivalent of a startup CEO—and team members who can play multiple roles.

Teams and Talent

Your new growth innovation teams should be small at first and staffed with cross-functional, co-located, and fully allocated (or nearly fully allocated) personnel.

It is better by far to have two people on a new venture at a 100 percent allocation than ten people at 40 percent.

Don Sheets, a Dow Corning executive who founded a disruptive internal startup called Xiameter that became a major part of Dow Corning’s business, looked for team members who had functional expertise and were good team players, but who were also “the-willing-to-stick-their-necks-out people.” He knew he needed to build a fast-paced and entrepreneurial culture, so when he interviewed people he liked, he would offer them the job on the spot as a means of confirming they were comfortable making quick decisions.6

While the teams are small, you should expect them—and empower them—to tap into the functional prowess of the core business to access capabilities when they need them. And, of course, they should benefit from active and engaged senior sponsorship.

One of the trickier aspects of team design is the need to realign performance metrics and incentives. New efforts can be replete with uncertainty. You want to entice top talent with an entrepreneurial bent who aren’t overly deterred by risk. You need to offer them some degree of upside for their participation, but it has to work in a corporate context with relatively rigid human resources guidelines. Senior HR leaders need to craft a talent management system with incentive packages that don’t constrain the strategy but propel it. For example, they should spell out the career path benefits that will come from the demonstration of good judgment and right behaviors, even if projects ultimately fail through no fault of their own.

Wiegand negotiates those dynamics by a focus on personal mission. “We look for people with a true passion for our vision,” he told us.

They need to have a personal connection to what we’re trying to do; it has to be part of what defines them as individuals. We would never succeed with people who are only partially committed, or who are in this because they find it interesting, or hope to use it to advance their careers. We look for people who see this as their opportunity to make a real difference, to build a legacy—because then they remain focused on the right things. I personally interview every applicant to the team to test for this—and across all of the offers we’ve made by now we haven’t lost one, because we pick the people who are truly invested in what we’re trying to do.7

Incubator Designs

In the early days of new growth strategies, your breakthrough innovation teams should be organized under an umbrella that is much like a start-up incubator, with dedicated teams vying for escalating rounds of funding as they build out and derisk their ideas.

Different types of incubator designs fit different stages of innovation development. Roy Davis, who was president of Johnson & Johnson’s Development Corporation between 2008 and 2012, uses a hospital metaphor to describe the roles of distinct but linked innovation organizations: “Early stage projects, that aren’t yet really businesses and have major assumptions to test, need something like a ‘neonatal ward,’ where there are specialized tools, a lot of support, and careful attention to nurture them to health. More mature projects, with early revenues but not yet at scale, can move to something like a ‘pediatric ward,’ where they’ll receive a lot more attention than they would in the general hospital.”8

Boeing created two linked organizations for its breakthrough efforts: Horizon X is responsible for seeding and shaping nascent beyond-the core-businesses that focus on futuristic technologies like hybrid electric jets and autonomous flying taxis, while Boeing NeXt manages them once they have attained revenue but are not yet ready to stand on their own alongside or within Boeing’s core businesses. As Logan Jones, vice president of Horizon X, put it, “Our job is to look over the horizon and do two things. One is to find ways to disrupt our company and ourselves before others do, and the other is to build a bridge to where innovation is maturing at a pace that big scaled enterprises aren’t naturally attuned to.”

Though some core processes and values may be non-negotiable, breakthrough innovation teams should be given as much freedom as possible to develop key processes like budgets and hiring, as well as rules, norms, and metrics that reflect their own unique missions. As Boeing’s Jones put it, “the concept and structure of Horizon X came from failing. We had a sub-optimized innovation organization for years before Horizon X and NeXt existed and I was a proud leader of it. The problem was that it was buried within a business unit.” Horizon X was set up as a separate limited liability corporation to isolate its risks and liabilities from the rest of Boeing. Reporting directly to senior management allows its leaders to “get decisions made and move out with velocity.” All of that was accomplished, Jones quipped, “through that less than sexy mission of governance, process, and structuring.”9

Dual Transformation

Many visionary future-back strategies call for both a repositioning of your current businesses and the creation of a new, beyond-the-core effort. To manage that, Innosight developed the concept of dual transformation, in which the core and new growth business are managed as both distinct and linked transformations, rather than as one monolithic effort. As noted earlier, this is covered in detail in the book Dual Transformation.

Transformation A is what you do in your core business to maximize its resilience into the future while generating sufficient cash to pay for new investments. Transformation B is your new growth platform, whether acquired or developed organically—or, most commonly, as a mix of the two. Leading, organizing for, and executing B is a primary focus of this chapter, given how foundational it is to the successful implementation of visionary strategies.

The dual transformation model is designed to give B initiatives the autonomy they need to discover their own business models and develop appropriate rules, norms, and metrics. They should be connected enough to the core (via C, the Capabilities Link) to selectively leverage its capabilities while funneling newly developed capabilities back to it when appropriate. This is a difficult balance to strike, and it requires the active engagement of senior leadership. One useful mechanism to manage the balance is what we call exchange teams—small units empowered to arbitrate sticky issues, like how to approach customers for the new business who are still being served by the old.

A classic example of the dual transformation model comes from our colleague Clark Gilbert’s experience as CEO of the Deseret News, a leading newspaper in Utah. As its leaders stared down the disruption presented by the rise of online media, they had to make some existential choices. While online media presented new opportunities, none were as profitable as the newspaper, even as its growth declined.

Gilbert’s solution was to modernize the newspaper, leveraging the best digital tools he could get his hands on to bring it online, while pulling separate online ventures out of it (for example, entertainment guides) and developing them independently. Gilbert himself adjudicated disputes between the two groups, leveraging the newspaper’s content to power the new ventures while channeling the digital tools and capabilities that the new ventures developed back to the newspaper.

Setting Up the Right Process

Beyond-the-core initiatives must be highly disciplined, but in a different way than those in the core. You cannot default to a present-forward mode; there are simply too many risks and unknowns in your new business model, calling for an emergent, test-and-learn approach. Both the senior team and the innovation teams should approach implementation as a learning process, embracing productive iteration and continually deepening and strengthening the abiding vision.

Creative problem solving and a discovery-driven approach to project planning are critical skills at this stage. Senior leaders and new growth teams should employ an innovation process that systematically identifies the assumptions most critical to the success of their proposition and then tests them in a targeted and orderly manner to prove or disprove their viability (and by extension the viability of the new initiative).

There are well-developed methodologies to guide this sort of work, such as Rita McGrath and Ian McMillian’s Discovery-Driven Planning, materials produced by the Lean Startup movement, and the Innosight toolkit for accelerating innovative initiatives, laid out by our colleague Scott Anthony in his book The First Mile.10 While innovation teams test assumptions related to their specific initiatives, the senior team should use the explore–envision–discover mentality to interrogate the direction and viability of the overall strategic program. As innovation teams learn and pivot, changing elements of their business model as it comes into contact with their customers, senior teams should do the same, adjusting the overall vision narrative and changing elements of the strategy as it comes into contact with the future. This learning orientation helps limit risk. Implicit in it, again, is the willingness to end projects that aren’t working. In fact, in order to weed out the weakest initiatives, we find that it’s advantageous to ask proactive questions like, Why shouldn’t we kill this venture?

Step 2: Implementing Your Strategy

The work of breakthrough innovation can be likened to a quest. Although some breakthrough initiatives can take a decade or more to travel from the drawing board or the laboratory to scale, most take shape within a three-year span. In our experience, creating a vision, developing a future-back strategy, programming the strategy, and preparing your organization to launch it should take up year one. Then it’s time for implementation, which takes you into year two and beyond.

As your pilot initiatives get off the ground, your immediate goal is to put points on the board by making progress on early-stage milestones, proving key assumptions, and achieving some quick wins. It’s also critical to enact changes in your core business to create the cash flow that will be needed when it’s time to ramp those initiatives up. In complex, multidivisional enterprises, the future-back strategy should cascade down to business units and even product lines as each develops its own future-back position in line with the new vision.

In year three and beyond, you begin to scale where you can, while making necessary adjustments to your systems to make sure that your changes to it stick. Your new strategy should increasingly be seen as the strategy.

You’ll almost certainly face a series of crises in the course of your journey, as Mark and his coauthors describe in Dual Transformation.11 One is a crisis of commitment. Any ambitious growth agenda will have its share of fumbles and false starts. There will be valley-of-death moments, when money is being spent but the turn toward accelerating revenue and profitability has yet to be seen. Another is a crisis of conflict. As we’ve noted, when new business initiatives start to draw in more capital, they compete with the funding needs of core businesses and the knives come out. Leaders need to demonstrate a steadfast commitment to the new growth efforts, helping to guide and shape them while fending off challenges from skeptical and even hostile colleagues, boards of directors, and outsiders.

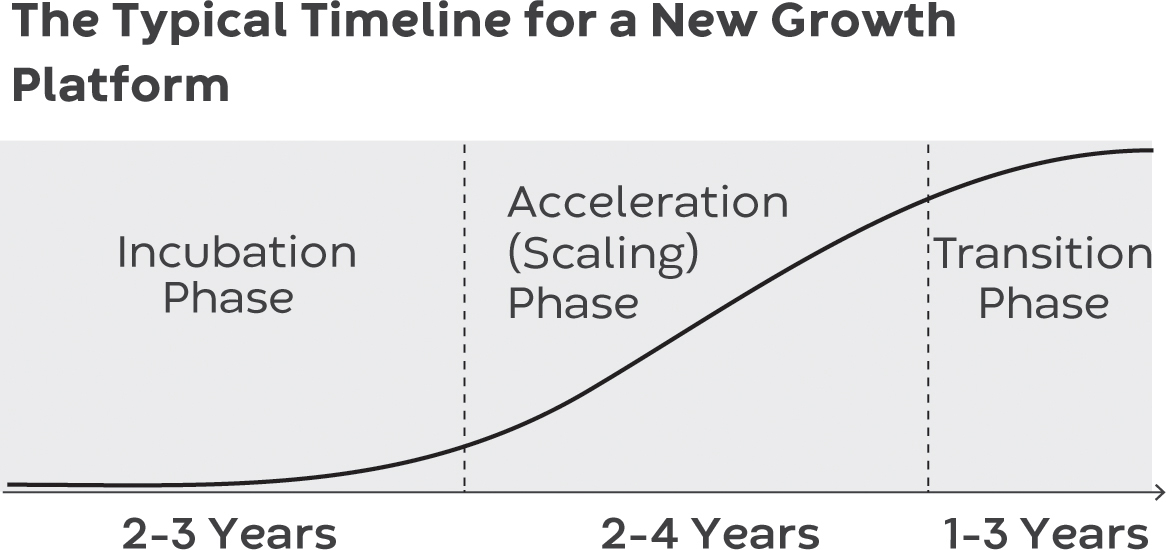

As for the initiatives themselves, most pass through three stages as they mature: incubation, acceleration, and transition (a process that Mark covers in detail in his book Reinvent Your Business Model).12 Like Boeing, companies can set up organizations specifically designed for each stage.

During incubation, the assumptions most critical to the success of the business proposition are established and tested. In the acceleration phase you’ll have much more knowledge relative to assumptions, so the focus is less on experimentation and more on setting up, refining, and standardizing repeatable processes, establishing the business rules that govern them, and defining the metrics that will chart their efficiency and profitability. Transition is when you determine whether the new business can be integrated into the core or if it should remain a separate unit.

As a set of general guidelines, a new business should be kept separate from the core when

- it calls for a significantly different set of business rules and accompanying metrics, which will evolve into significantly different norms

- it requires a distinct brand to fulfill its value proposition

- it tends to be disruptive to the core business model, making money with a lower margin, requiring new capabilities, or a different cost structure

On the other hand, it may be possible to reintegrate a new business into the core if

- its profit formula is substantially similar to that of the core business or provides greater unit margins

- it enhances the core brand in some significant fashion

- it can transform and improve the core

Nespresso: A Slow-Brewing Success

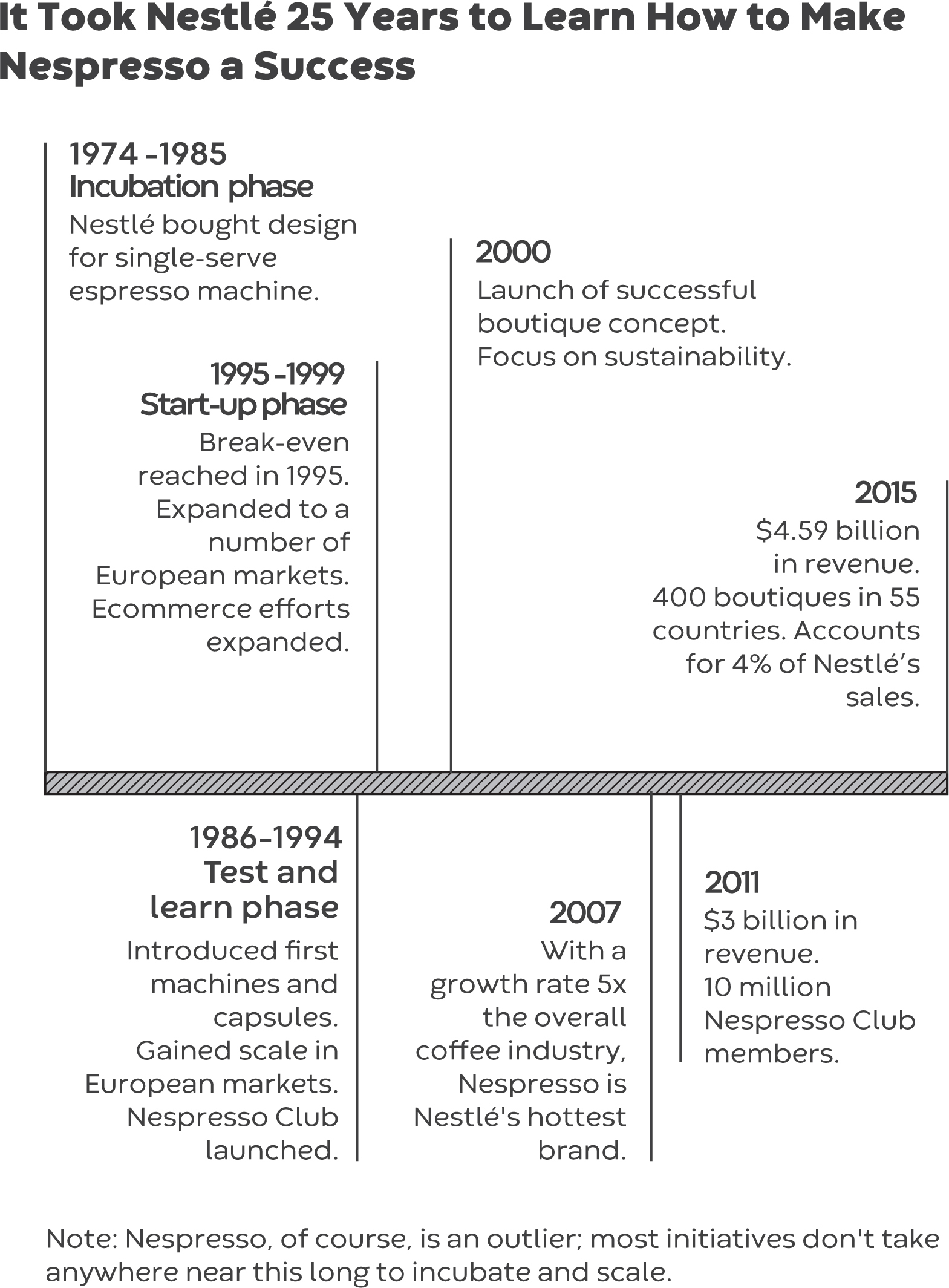

Today Nespresso is a household name, but its global success didn’t happen overnight. Nestlé acquired the basic design for a single-serve home espresso maker in 1974 and introduced it in a few European markets in the early 1980s. Breakeven didn’t come until 1995. In 2000, the same year the product debuted in North America, Nestlé changed its marketing model and began to sell the product in “boutiques” in department stores. With its new elite cachet, Nespresso’s sales increased by double digits year over year for nearly a decade. Hiring George Clooney as its spokesperson cemented its elite brand proposition even more. By 2015, Nespresso was a $4.5 billion global brand, and it continues to show mid-single-digit growth.

Setting Anchors

Given the time it takes new ventures to find their feet, you will inevitably be pushed to justify and re-justify the investments they require. As Hait puts it, “Leaders need to provide a constant activation energy to keep the program alive, or else it gets swallowed up. You work so hard to get the satellite in orbit, but it immediately starts to fall back to earth if you don’t keep it up. The inertia of a big company will pull it back. Even if you succeed in setting up a separate group, others will constantly be poking at you. You need a steady drumbeat of success to stay ahead of the barbs, which is especially hard to do in areas that are unproven and inherently risky.”13

That’s why Hait stresses the criticality of near-term moves that bridge the objectives of both the new growth strategy and the core business—strategic choices we have come to call anchors. Anchors are moves—usually acquisitions or major partnerships—that in a single stroke make the strategy more real by bringing it heft and momentum. They generate early revenue, providing an additional funding mechanism for the new growth strategy, and bring an influx of talent and capabilities. The best anchors also create tangible value for the core business, generating goodwill and helping to keep skeptics at bay.

By 2018, the World Without Disease group’s efforts in lung cancer had progressed to the point where J&J was ready to make a significant commitment, creating what they called the Lung Cancer Initiative and bringing in Dr. Avrum Spira, a physician/entrepreneur with expertise in the early detection and treatment of lung cancer, to head it up. Working in partnership with Ethicon, J&J’s surgery business, Hait, Wiegand, and Spira quickly found their anchor, and in April of 2019 J&J acquired a Silicon Valley startup called Auris Health that had developed and recently launched the first robotic bronchoscope.

“One of the primary unmet needs that keeps us from effectively finding and treating lung cancer early, while it can still be cured, is that it is very hard to access suspicious lung lesions in order to confirm whether or not they’re cancerous,” Spira explains.14 The Auris Monarch platform aims to change that by making it easier and more efficient for pulmonologists to reach deep into the lungs to sample suspicious lesions. As Hait puts it, “Colorectal cancer screening is well established with colonoscopy. Doctors use colonoscopes to simultaneously screen for polyps and sample them to make sure they’re not cancer. Lung cancer has remained so deadly, in part, because we don’t have analogous tools such as a ‘pulmonoscope.’ We have recently started screening for suspicious nodules with Low Dose CT scans, but screening without effective means of confirmation has limited value. Now, with platforms like Monarch, we can complete the equation by more readily accessing tissue for biopsy through ‘pulmonoscopy.’ ”15

The Monarch platform is an important step toward the larger vision of intercepting lung cancer, and it presents an opportunity for further development. For example, Spira’s team is working with colleagues at Janssen to develop immuno-oncologic agents that can be delivered directly to the site of a tumor through the Monarch scope, theoretically increasing their efficacy.

Too many corporate startups fail because it takes them too long to make tangible progress. The Auris acquisition helped put the Lung Cancer Initiative on the map, giving it an identity as something more than an exciting idea. Best of all, it fit within Ethicon’s future-back strategy as well. It was truly win-win, which helped ensure corporate support for the $3.4 billion acquisition.

Creating a vision, translating it into a future-back strategy, and then programming and implementing it is not a discrete event within a corporation’s life. In a way, it is its life. The work is never done; visions and strategies must constantly be tested and adjusted. Meanwhile, there is always more future ahead of us, so newer ventures must be constantly begun. As such, future-back needs to become an organizational capability, led at the top, and permanently embedded in leadership mindsets, strategic planning processes, and organizational culture.

Chapters 6 and 7 will describe some of the ways you can institutionalize these capabilities and make them routine.