1.1 The Decision-Making Process

1.2 Challenges in Today’s Organizational Environment

1.4 Management’s Goals and Expectations

1.6 Organizational Change Management

1.7 Selling the Benefits of EPM

Nothing worthwhile in business was ever accomplished, unless it was done by a monomaniac on a mission.

—Peter F. Drucker

Let’s begin at the beginning with a definition. The Project Management Institute defines portfolio management as: “the centralized management of one or more portfolios which includes identifying, prioritizing, authorizing, managing and controlling projects, programs and other related work, to achieve strategic objectives.”

In order to be successful in delivering an EPMS that will significantly benefit the organization, you must understand that you are going to make a significant change to how the organization operates, and any significant change can expect to encounter resistance. You need to understand the organization’s current problems and priorities, define the solution, and be prepared to overcome resistance. You must truly believe you are going to make a difference and to dedicate your efforts to making it successful. As the change leader, everyone is looking to you to make this work.

What we’re going to talk about in these next sections will help you see the strong benefits of enterprise portfolio management, help you convince others of those benefits, and become the leader in implementing the effort. How much improvement should you expect? The following graphic from PMI’s Pulse of the Profession1 should help your management understand:

For a more detailed analysis of how to prepare the organization, see Chapter 5 of Project Portfolio Management Strategies for Effective Organizational Operations.2

Historically, organizational strategy* has always been challenging to accomplish. Most strategic goals are changed before they are ever met in response to rapidly changing market conditions. Quoting Mark Cotteleer of Cutter Consortium “Saying something is a strategic investment is about as productive as saying, ‘This is something cool that we want to do.’” Yet if we select the right projects, we can be more successful. If a project does not support the organization’s strategic direction, why are you doing it? “If you want to find out where your company is going to be three to five years from now, don’t look at your stated strategy. Instead, look at your Project Portfolio. That’s where you’re making your investments, and it’s those investments that determine your firm’s direction”.3

Figure 1.1 Improvements resulting from enterprise portfolio management

In 2012, the international bank PNB Paribus discovered it was spending 70 percent of its project money on compliance projects and only 2 percent on new products. This led the executive director to state that “We will be a very compliant bank with no customers.”

As Intuit’s founder Scott Cook put it, most decisions are based on “politics, persuasion, and PowerPoint”. According to Bivins,4 the traditional way of determining which projects to do is called BOGGSAT:

BOGGSAT is an acronym for “bunch of old guys/gals sitting around talking”. This is a common method that produces decisions that are often painfully slow, unproductive, and of poor quality. Although it is the most common decision approach in use today, BOGGSAT is not appropriate for complex decisions such as project portfolio selection and determining benefits. A major reason BOGGSAT fails as a decision technique is that, as psychologists have found, the average human brain can discriminate among only seven elements, plus or minus two, and can hold in short-term memory only seven objects, plus or minus two. That is, we humans have cognitive limitations that prevent us from mentally processing the complexity that exists in PPM selection decisions.

There is a better way, and that’s what this book is about.

The concept of managing multiple independent projects within an organization was first proposed by McFarlan5 in 1981 as a more efficient way to deal with the risks in IT projects. According to Payne,6 up to 90 percent of all projects within an organization by value occur in a multiproject environment.

Most of the literature definitions of portfolio management revolve around selecting and managing project in support of the organization’s strategic goals. This is a good way to approach the topic. However, looking at the reality of what projects organizations are doing, we see that a great many projects, especially in the IT group, have little relation to long-term strategic goals but are done to fix existing problems or to make short-term improvements. We’ll discuss how we can combine all the project work whether strategic or operational.

Even in the mid-2000s, a portfolio management approach was oriented only toward selecting the “best” projects for an organization to implement strategic goals. More and more portfolio management is taking on the roles traditionally done by a project management office (PMO) and getting involved in how projects are being managed (governance) and in benefits realization. The lines between the two areas are getting blurry as organizations attempt to find the most effective and efficient approaches to achieving their strategy. Research done jointly by the Project Management Institute and Forrester Research (Forrester7) shows that Project Management Offices are increasingly getting involved in portfolio management and governance as shown here.

Figure 1.2 PMO involvement

You can select the best projects for the organization, but if they’re badly managed, the money will be largely wasted. Organizations with good, mature project management processes can do projects less expensively and more quickly than organizations with a low project management maturity level. We’ll discuss this later in the book.

While portfolio management has reached widespread use in IT, there are significant advantages to expanding it enterprise-wide. In the construction industry, for example, a significant issue is to allocate personnel and equipment across multiple construction projects. Portfolio management includes processes for identifying how best to spread resources around and can alleviate that problem. There is no profit-making organization in the world that has unlimited resources. Making the most efficient use of those resources is only part of what an enterprise portfolio management system (EPMS) can provide.

Most enterprise portfolio management systems (EPMS) in real organizations are managed by an enterprise-level Portfolio Management Office (EPMO). This is not a mandatory requirement, just a convenient way to work. The detailed division of roles and responsibilities between the EPMO and the EPMS must be defined clearly within your organization. Does the EPMS monitor and track existing projects or is that done elsewhere in the EPMO? Who can recommend projects be killed? The EPMS or the EPMO? These and other items need to be clearly defined before the EPMS is created.

One caution before you start: It is the tendency of every project manager to want to design the most sophisticated and “best” product possible. But the reality of how useful an EMPS is depends on the data fed into it by people who want to get their projects selected. As Cooper8 said “… saw this time and again: portfolio task forces designing and trying to implement very exotic portfolio methods, only to be thwarted by the very poor quality of the data inputs”. The goal is to create and deliver a system that will benefit the organization and that people will find it easy to use.

There are three basic approaches to developing an EPMS. The first is to design the system and the processes, develop it yourself, and host it on your IT infrastructure or in your cloud service. This gives you the greatest flexibility, the greatest privacy, and the most control over your portfolio. Hosting it internally generally provides greater security so long as your IT department provides good security firewalls and processes.

The second is to identify your new processes and buy a software package that supports your needs. Since no commercial package will provide exactly what you need, you will have to customize it and adapt it to your specific requirements. There’s usually an annual fee for a complex package such as this. You can host it yourself or pay the vendor to host it.

The third approach is to buy an EPMS as a SaaS (Software as a Service) product or a cloud based product and have the software vendor host your system. In this approach, you can implement much more quickly because the configuration has already been done by the vendor. You are basically just leasing the software from them. Why would you not use this approach?

• You can’t configure the system in a way that’s best for your organization;

• There are on-going maintenance costs that continue as long as the vendor hosts the system; and

• You are giving your internal and proprietary information to an outside party for hosting your data.

Since most portfolio management vendors that offer SaaS charge by the seat, the costs can easily run into tens of thousands of dollars per year whereas rolling your own EPMS is a one-time expense (plus on-going internal software maintenance costs and occasional updates).

Step 1.1 The Decision-Making Process

1.1.1 The Decision-Making Process

Man is not a rational animal, he is a rationalizing animal.

—Robert Heinlein in the short story Gulf, 1955

The goal of portfolio management is to facilitate the decision-making processes involved in selecting the projects that best move the organization toward its strategic goals. These processes provide management the information they need, and only the information they need, to decide which projects to select. One of the major difficulties in designing the system is to understand what information management really needs and setting up the filters and priorities to improve the project selection decisions.

A properly designed system takes into account its own limitations, primarily the inability of an algorithm-based system to make perfect selections on which projects should be prioritized and funded. Corporate strategies change, technologies change, the economic environment changes. The human brain is much better adapted to filtering all the parameters of a continually changing environment than any software based system. The downside of the human brain is that it is biased. Think about it. Haven’t you run into people who look at the data you are presenting and just refuse to change their mind despite the data? We have all dealt with people like that.

There are always more ideas for new projects then there is time and money to do them, and the ideas come from all parts and all levels of the organization. Everyone has an opinion on how to improve, so we will design our system to accept inputs from anyone in the organization without filtering. The system will filter the inputs based on criteria determined by upper management and then present a list of possible projects with recommended priorities taking into account resource and budget constraints. Management will have the opportunity to select the best projects based on the information. They are not constrained with blindly following the list presented but have the option of selecting projects that rank closely together in the prioritized list.

Decision making is not an end in itself, it is a means to an end. The goal is not to make a decision, but to solve a problem or to make a change, such as selecting the “best” projects to approve, and then take action to implement the decision. To ensure we make rational, unbiased decisions that produce the results we want, critical decision making requires you to:

• Obtain complete and accurate data

• Examine your logic and your biases

• Examine your premises

• Be aware of your motivations

• Think through both short-term and long-term impacts

• Know your “flight” envelope—what can you do efficiently and what will be a large stretch in your capabilities

• Check with others

• Be comfortable with uncertainty

A decision requires several things:

• An event that drives a need for a decision

• A timeframe within which to make the decision

• Facts and information that need to be taken into account

• A desired positive outcome

A decision also requires assumptions about:

• Things we don’t know—what can we safely assume?

• The facts themselves—are they accurate and unbiased?

• The outcomes of the decision—can we predict the future accurately enough to select the best long-term solution?

• Our own objectivity and the objectivity of people giving us information

• The acceptability of the decision—will everyone involved fully support our decision?

Most of us consider ourselves competent decision makers based on our own history of making reasonable decisions in the past. Yet there is a great deal of recent neurological research that indicates our brains really are not normally logical, in fact, most decisions are made by the most lazy portion of our brains and only later justified, if questioned, by the rational portion of our brains, the cerebral cortex. Once a person has made a normal, noncritical decision, they search for data to support that decision rather than the other way around. Managers do this all the time because they very often have to make decisions with minimal data and are forced to rely on their experience. They make a decision, and look to justify it.

Because decisions are heavily influenced by how the information is presented to us, a better approach is to have a gatekeeper in charge of collecting the data and presenting it in a complete and unbiased format to the decision makers. This is what a well-designed portfolio management system does.

1.1.2 The Decision Environment

At the working levels of the organization, it seems obvious which projects should be done—the projects that provide the greatest benefits. The assumption here is that the projects selected should have the greatest benefits to “our” part of the organization. The lower in the hierarchy, the more narrow the viewpoint and the shorter the time outlook.

The decision on the best project is not as obvious as you go higher in the organization. The upper management team and the executive level have multiple groups and divisions they are responsible for, if not the entire organization. They must decide which parts of the organization to allocate the money to for the projects. Priorities in multiple parts of the organization must be balanced against each other based on assumptions about the future. Not just the near-term future, but how to position the organization five years from now. Unlike Warren Buffett, who once famously said “My idea of a group decision is to look in a mirror”,9 these decisions require the focused and committed agreement among multiple high-level stakeholders each of whom has a different priority and vision.

The decision environment takes into account not only the organization, its resources, and its strategic goals but also the external environment. Every organization, whether government, privately owned, publicly owned, or nonprofit exists in the overall environment and is heavily influenced by that environment. The environment consists not only of the economic environment and physical environment, but for privately-owned and publicly-owned organizations, also the competitive environment. What our competitors are doing now has a direct influence on what we will be doing in the future.

The future is unknowable. (If it were, psychics would not sell their services but would be playing the stock market. Any store-front fortune-teller is a phony.) Accurately predicting it requires developing organizational capabilities that may not pay off immediately. For the long term, projects should be selected not just for their short-term financial benefits but to develop future new markets and knowledge growth. These are termed exploration projects and often go un-selected because their ROI is unpredictable, but they will build the capabilities for the company’s future growth and profitability.10 The CFO should never be the final decision maker because they are always focused on the short term and tend to be very risk averse.

These exploration projects are potentially the most beneficial ones because the products they produce will be the organization’s future. Sony changed the whole music world with the Sony Walkman in 1979, Apple changed it again with the iPod in 2001. In between the two, Sony improved its original Walkman, but with only one major change— to create a CD-based portable player. There were no other substantial, ground-breaking changes. When the iPod was released, it completely overtook Sony’s bread and butter income stream in portable music players.

The history of modern-day management is rife with stories of poor decision making at the highest levels of the organization. Xerox famously sold a young Apple Computer the rights to develop the GUI interface because the executives at Xerox headquarters on the East Coast did not believe the Xerox West Coast scientists had anything useful to offer. Kodak invented the first digital camera in 1975 but their income stream was from selling film and management shot down any project that threatened that income. IBM invented the first really usable PC but was unable to get any priority on it because the decision makers viewed the company as a mainframe company and wanted nothing to threaten that. These are the kinds of decisions that can either make or break a company in a changing external environment. Our job is to make the best case for these exploration projects so show the future benefits are greater than the high risks involved in doing them.

Project decisions are based on the best analysis of the environment. But no decision maker is perfect. As Davies11 states:

CEOs are naturally wary of some investments. Large capital projects in politically unstable countries, common among companies in the mining and oil and gas sectors; speculative R&D projects in high tech and pharmaceuticals; and acquisitions of unproven technologies or businesses in a wide range of industries all carry what many see as an above-average degree of risk. The potential returns are alluring, but what if the projects fail?

Weighing the pros and cons of such deals, executives delve into the usual cash-flow projections, where they often make one seemingly small adjustment: forgetting what many of them learned in business school, they bump up the assumed discount rates in their cost-of-capital calculations to reflect the uncertainty of the project. In doing so, they often unwittingly set these rates at levels that even substantial underlying risks would not justify—and end up rejecting good investment opportunities as a result. What many don’t realize is that assumptions of discount rates that are only three to five percentage points higher than the cost of capital can significantly reduce estimates of expected value. Adding just three percentage points to an 8 percent cost of capital for an acquisition, for example, can reduce its present value by 30 to 40 percent (depending on its long-term growth rate).

1.1.3 Where Does the PMO Fit?

Understanding how successful PMOs fit in the organization helps us understand the level of decision making that we’re dealing with. According to Forrester12 research, successful PMOs have the following attributes:

• They have a seat at the executive table. Strategic results require strategic positioning. PMOs that are highly effective in driving business growth report to varying levels of executive management, ranging from senior vice president to the C-level, and are regarded as members of executive management. Champions are strategically positioned, too. The majority of the leaders interviewed have highly visible sponsorship at the C-level.

• They are a vital part of the strategic planning team. Since portfolio management is a core competency, PMOs actively participate in strategic planning and help shape strategy by providing feedback to executives about performance, labor costs, and customer feedback.

• They embrace core competencies. Excellence in project management remains a critical capability for PMOs. The most successful organizations recognize the specific role of the project manager and build significant learning and development programs to mature project management skills.

• They use consistent objectives across industry and regions. Customer-facing or business-facing, strategic PMOs share

the same objectives: Drive success through alignment with business stakeholders and operational excellence. Meeting these objectives is differentiated by such factors as orientation, region, and culture.

Step 1.2 Challenges in Today’s Organizational Environment

1.2.1 Background to Organizations

An organization of any type is a living entity. It grows and expands when environmental conditions are right. It contracts, often painfully, when conditions are poor. All parts of the organization work together, more or less efficiently, toward the goals of the organization. The environmental conditions for a small not-for-profit are vastly different than they are for an international, for-profit organization or for a government organization. Yet each organization responds to its specific environment.

In an organization, nothing is done in isolation. All company activities are done in an environment created by all the other company activities as well as by the organization’s competitors and outside environment. Whether or not a project gets approved and funded depends on how that project benefits the organization in comparison to the other projects being considered in the existing environment.

This internal environment includes the culture of the organization, its financial capabilities, its geographic location(s), the legal and regulatory framework it operates in, how well established its internal processes are, its technology infrastructure, internal competitiveness between and among the divisions, and all other internal influences. Some organizations, such as General Motors before its bankruptcy, are intensely competitive internally to the point of becoming dysfunctional. For an interesting read, look up the history of GM’s Fremont, California, factory. The labor/management relations were extremely poor, resulting in the worst quality record in the industry and a high percentage of absenteeism among the workers. GM fired all the workers and sold the plant to Toyota. Toyota rehired the majority of the workers, changed the relationship with them, and produced high quality cars much more efficiently with the same workers.

Story

The author had some personal experience with this approach to decision-making while leading the requirements development team for a major infrastructure improvement. When TRW Information Systems changed their name to Experian in November 1996, they did so to create a unique name that showcased their advanced credit processing system. This new system had spent two years in development with the programmers writing about 5 million lines of new code to change from the flat file data base they had been using to a fully-relation data base (IBM DB2). This effort took an extensive amount of overtime during the development process to meet deadlines. The company was sold to the investment firm Bain who turned around and sold it to Great Universal Stores in Great Britain. When the sale was announced to the employees at an all-hands meeting (which had to be held outside because there was no room big enough in the office buildings), the executives were completely enthused about the sale. It was reported the next day in the Wall Street Journal that the executives were paid a significant amount of cash for the sale. A month later, a memo came down from the executive layer to the software engineers who made the sale possible that they would not receive their annual bonuses. Bonuses were tied to market share and because the developers were completely engaged in the new system, there were no new products released, market share had gone down, so the developers would not receive any bonus. The author headed up the systems engineering group that developed the requirements for the new system and was extensively involved in the development effort. Needless to say, by the middle of January, a significant percentage of the experienced development staff had mailed out resumes and were job hunting.

Other organizations are internally highly cooperative, and some organizations are so big that they are internally competitive, such as Hewlett-Packard before its 2010 reorganization, that they do not even realize that divisions are competing with each other because of poor internal communications among upper management. An organization where the directors and executives are highly competitive with each other only creates an environment that discourages communications.

Think about the organization that you will be implementing the EPMS into. The culture will dictate the details of the approach you will plan out.

While project managers don’t like to deal with constraints, the reality is that project management exists within the physical, cultural, and economic environment of every company. Your ability to manage projects is constrained by many factors outside project management itself. These limitations extend to the EPM system itself and, in fact, are major inputs to the filtering criteria used to analyze and approve projects.

While we would love to believe that organizations are well-planned entities that are focused on their long-term goals, have well-designed internal processes, and provide a highly-rewarding experience for their employees as well as many benefits to their external stakeholders, this is not the reality of life today and probably has never been the reality.

Many organizations are poorly planned to start with and deteriorate from there. They start out small and develop internal processes that are sufficient to help them operate in their existing environment. The emphasis is on survival and growth and not on efficiency. The rapid growth, and even more rapid death, of most dot-coms is a good example.

As organizations grow, their internal processes grow with them until it becomes obvious that the processes no longer work. Processes are created as needed and rarely documented. At some stage of growth, the organization is large enough that this ad hoc management style no longer works and professional management is brought in. Processes are re-designed, maybe documented or maybe not, and for a while, the organization continues its growth in a more planned fashion.

As growth continues, these re-designed processes are also overcome and become less efficient. Redesigning them is not a high priority so the inefficiencies are lived with until it becomes obvious to upper management that there are serious internal problems (the employees saw these problems long before management did). Further, in an expanding business environment, a lot of growth occurs through mergers and acquisitions (M&As). When two companies merge, their existing processes are rarely merged effectively and the resulting entity becomes less efficient as employees struggle to figure out how to do their jobs. When the employees are treated poorly by upper management, they are not likely to support any change.

1.2.2 Challenges in Today’s Project Management Environment

The parts of the organization that are impacted the greatest by changes are the layers at which, sorry to say, much of the project management work is done. In today’s rapidly changing, internationally-competitive environment, management is under a lot of pressure to reduce costs and to become more profitable. The normal approach is to reduce headcount, either by laying off staff, by attrition, or by outsourcing to the current low-cost provider somewhere else in the world. The result of this approach is to put more work on fewer people.

This means that a very typical project environment involves both the project manager and the team working on several projects instead of being focused on one. Everyone is multitasking, with well-researched and documented reductions in productivity.13 When you’re working on five different things, you can’t be as effective or as efficient as when you’re concentrating on just one or two. This was researched thoroughly14 with results shown in the following figure:

Figure 1.2-1 Impact of multitasking

In the IT department, the situation is even worse, the staff there not only works on projects, they are usually working on daily operations and at the same time: bug fixes, application upgrades and implementations, system maintenance, security patches, and so on. All of which distract them from project work. Recent research on multitasking shows that doing multiple things at the same time is equivalent to an IQ drop of 10 to 15 points, the same IQ drop as smoking a joint of marijuana.

In addition to the reduced productivity, more mistakes are made leading to more work having to be checked and redone. Rework, which is always unplanned, has ripple effects because it takes people away from what the planned work was, further impacting projects in work. There is a large body of research on the negative impacts of multitasking. See, for example, Bannister and Remenyi.15

Law of Project Management |

There’s never time to do it right. There’s always time to do it over. |

Many, perhaps most, mature organizations share the same problems and internal situations.

At one company, while the author was implementing a PMO for them, an IT project started based on a request by a senior executive. The project was to implement a product web site. It was approved and given to IT to implement. After six months, IT told the executive that the project was in work. Six months later, they told him it was in work. Again six months later, and six months after that. After two years of hearing that the project “was in work,” the executive asked to see the results to date. At that point, IT had to admit it had started the project, but actually hadn’t done any work in the past 18 months because there were other priorities that had come up. At this point, the project was canceled as being too late to be useful.

Let’s face it, managing a project in the typical organization is highly challenging. We are often using a central pool of personnel that are working on multiple projects. Our “teams” often do operational work outside of projects. Management’s typical response to this situation is sometimes derogatorily referred to as “Peanut Butter Resource Management”—we just spread the people around over more and more work.

Too many factors that impact projects are outside the project manager’s control. Worse, in many organizations, there is no common agreement on what a project manager should be doing. Functional managers do things the way they have always done them and consider the project managers to be schedule keepers. This is very frustrating to the project managers.

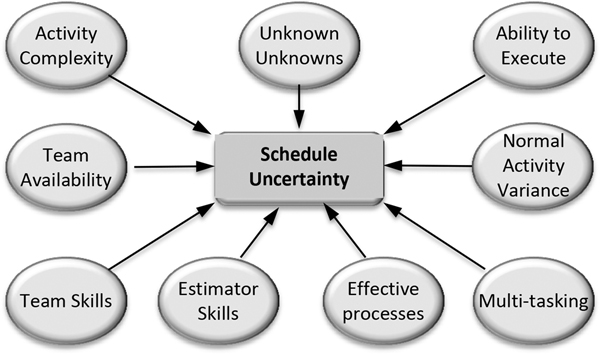

Strong inter-dependencies among multiple projects compounds the problems. These dependencies can be created by sharing personnel, equipment, facilities, or by competing for limited funding. A problem on one project quickly spreads to others (think of the cascading reaction in a nuclear bomb). For example, scheduling uncertainty on one project means we don’t know exactly when tasks will happen. When one task on that project runs late, there’s an impact on other projects that need those resources. This makes scheduling projects in a multiproject environment very challenging and is a major source of projects running late. It is also a strong driver to implement an EPMS and to install an enterprise-capable project management tool.

Creating accurate schedules is subject to a wide variety of influences as shown here:

Figure 1.2-2 Inputs to schedule uncertainty

All of which lead to uncertainty in the schedule. In a multiproject environment where resources are shared, as we have just seen, there is an additional, and very strong, cascading effect from other projects that are scheduled to use the same resources as we are. Any slippage in one project impacts the other projects that have scheduled that resource.

In the manufacturing industry, there is a well-known constraint called Little’s Law. It says that cycle time equals the work in progress divided by the throughput:

CT = WIP/TP

In order to improve how quickly projects get done, reduce the number of projects you’re doing. By recognizing that “things will happen” to disrupt the plan, leave people the ability to recover from unplanned changes instead of forcing them to work continual overtime.

We can view a multiproject environment as a complex system. There are interdependencies among the various components of the system (as shown by the previous example of shared resources). The field of systems analysis teaches us that one characteristic of a complex system is that responses are nonlinear. You don’t always get the same response from the same input. A response to a particular demand for a resource is not a repeatable event, it is dependent on the time in which the demand is made. We would likely offer the resource to another project next week but we can’t offer it today because we need that resource. Same request, different response.

Other typical impacts we commonly see are that adding resources to one project usually means removing them from other planned work, often another project. Increasing overtime means lowering productivity. Adding more projects reduces the ability to finish any of them on schedule.16 These are common situations that are often not taken into account before a change is made to the portfolio.

Because there’s a time delay between making a change and seeing the effects, complex systems are inherently unstable. The danger is to try and overmanage the full collection of projects. You cannot manage ten separate projects the same way you manage a single project. In this environment, flexibility is more important than rigid adherence to plans. Why spend weeks planning out a project schedule in detail when there’s a 90 percent chance the schedule will be impacted by other things?

Another area that is impacted by adding more projects to the portfolio without analysis is quality. The more overworked people are, the lower the resulting quality in the project, in the product, and in the decision-making process. Quality in a physical product can be measured and there are many quality systems that are in commercial use. Quality in processes and in decision making is much more difficult to quantify and to measure. Mistakes are made more often but they are rarely traced back to the fact that people are seriously overworked, tired, and making bad decisions.

An interesting experiment in quality improvement17 led to the following conclusion: “When the quantity goal is easy to achieve, setting a difficult quality goal results in increased quality. When a difficult quantity goal is set, setting a difficult quality goal does not result in increased quality.” In other words, when your people are not overworked, quality improves.

In a complex environment there are many of these impacts and inter-dependencies that are not knowable in advance. No one in the organization understands the entire set of projects in work or their inter-dependencies. A functional manager that needs a resource from a project may not realize that obtaining that resource impacts not just one project, but several projects that had scheduled that resource.

This is where an EPMS can be most beneficial. A common solution is to use a PMO to provide the infrastructure within which the EPM system can exist. The PMO provides a central location for all information related to projects in work. It presents the information in a way that allows management to understand what’s going on in all projects.

In order to overcome the objections that will be raised by the managers and division heads that don’t want an EPMS because it reduces their control, the person implementing the new system must understand all of these constraints, problems, dependencies, and impacts and prepare to counter the arguments that will be raised.

1.2.3 Projects, Programs, and Portfolios

We talk about projects, programs, and portfolios. How do they all fit together? Sometimes it can get confusing. Both programs and portfolios include multiple projects. Often when we talk about a program, we call it a project. What are the distinctions? Using definitions published by the Project Management Institute,18 we can define them as follows:

Project: |

A temporary endeavor undertaking to create unique products or services. |

Program: |

A group of related projects managed in a coordinated way so as to obtain benefits not available by managing them individually. Programs may include related work outside of the scope of the discrete projects within the program. |

Portfolio: |

A collection of projects or programs and other work that are grouped together to facilitate effective management of that work to achieve strategic business objectives. The projects or programs of the portfolio may not necessarily be interdependent or directly related. |

A good way to look at it is that a project is a specific effort to produce a deliverable, whether a new product, a service, a business process, or any other beneficial output. A program is so large and complex that it includes multiple projects to produce the outcome, such as a construction program, an engineering program, new aircraft development, and so on.

A portfolio is a collection of both projects and programs. A large portfolio, such as an enterprisewide portfolio, may include lower-level portfolios within it. This hierarchy is shown in PMI’s documents as:

Figure 1.2-3 Portfolio hierarchy

Since both programs and portfolios have multiple projects within them, what’s the difference? One way to look at it is that if a project within a program fails, the entire program fails. If a project within a portfolio fails, it doesn’t affect the other projects within the portfolio. Indeed, sometimes an IT portfolio is better off when a project fails because it frees up resources to work on other projects.

1.2.4 PMO Versus EPMS

There is confusion, particularly among commercial software vendors, about the differences between a program management office and a portfolio management system. In order to sell their products, the vendors frequently combine both of these functions into a single package, most often by buying existing independent platforms and somehow slapping them together into a single package (Oracle Corp. is notorious for doing this badly). As a general rule, these large software packages are clumsy and awkward and rarely deliver on the sales promises.

There is a clear distinction between a PMO and an EPMS. A PMO focuses on project management—providing templates and tools, assigning resources, keeping central databases for risks, offering support, and other project-management-specific items.

An EPMS is designed to select and prioritize projects. Nothing else. It is oriented toward supporting organizational strategic goals, not supporting operational items. In order to optimize resources, an EPMS may organizationally be part of an Enterprise PMO, but it does not have to be.

An EPMS should only be implemented for the long-term benefits of the organization. It has few benefits in the short term, and in fact the implementation process will be disruptive and confusing to many people in the organization unless they are properly prepared. Until people get comfortable with the EPMS and familiar with the changed processes, productivity is likely to temporarily decrease.

Long-term growth and improvement is the province of upper management. Ultimately the results belong to executive level under the overall guidance of the board of directors (in theory, anyway. In real life, the executives make the decisions and the Board often just approves the decisions that have already been made, rarely offering effective strategic guidance different than what executives recommend). Under various levels of presidents, executive vice-presidents, senior vice-presidents, and just plain vice-presidents comes the lower level of directors, and under them, multiple layers of managers. Further down, we have supervisors in those organizations that have a large level of working-level employees. At each level, the managers are working toward the growth of the organization in their particular area.

The higher up the management level, the more the person is charged with the long term improvement of the organization. These are the people who have to (a) buy into the benefits of enterprisewide portfolio management, (b) approve the funding and the resources for it, and (c) who will be members of the Governance Committee and the lower-level Steering Committees who will make the decisions on which projects to approve and to fund.

In a large organization you may have separate companies, divisions, or groups. Their relationship to the top of the organization will vary from completely autonomous, to semiautonomous, to completely controlled by the central organization. At each level, there are responsibilities commensurate with that level.

At the top level of every large organization, we have an executive Governance Committee or something equivalent. The members of this structure will make the highest-level decisions on where the organization’s money will be put in the next year’s expenditures. Below them, depending on how large the organization is, we have Steering Committees that make the same decisions for individual business units, divisions, or groups.

Ideally, the executive level sets the strategy and the portfolio manager takes this direction and drives it forward. In reality, conflicting priorities or day-to-day activities can often interfere. “To prevent this, the portfolio manager needs the executive support,” said Dr. Wanda Curlee, PMP, PgMP, PfMP, Director Portfolio and Program at Hewlett-Packard. The role of the CEO is to articulate clearly what a company’s future is in one-year, three-year, and five-year timeframes. The portfolio manager’s role is to evaluate the portfolio to ensure it meets the strategic goals, continually reviewing the company’s landscape for newer projects and programs that may need to be a part of the portfolio.19

A very simple organization chart for an international company might look something like this:

Figure 1.3-1 Organizational hierarchy option 1

Not all international companies are organized around geographic regions. Some are organized around product lines as illustrated in the following chart:

Figure 1.3-2 Organizational Hierarchy Option 2

Either way, enterprises organize in the way that makes sense to them. The exact organizational structure is important because it has an impact on how the EPMS is designed. Depending on the level of the organization that is doing portfolio management, an EPMS that is designed for one division or business unit of a medium-size consumer products company would have a very different structure than one designed for an international corporation that sells products worldwide.

With all these layers of people, who should make the decisions on which projects to fund? The primary criterion for who should be on the committee is that group of executives or managers who have budgetary control over that part of the organization. The ultimate responsibility for allocating the annual budget of the organization belongs to the executive level. As the budget is detailed down into different parts of the organization, there will be lower-level governance committees that make the decisions appropriate to that level.

If internal coordination and communications is good (usually not the case but let’s pretend for the sake of discussion), then the various levels have a good understanding of the strategic goals of the organization and how their area supports those goals. They then make rational decisions on the most effective way to achieve those goals.

As will be shown later on, there are various categories of the budget that are dependent on the strategic goals of the organization. The specific categories will depend on the level of the organization that is making the project decisions. For example, at the division or group level, there will generally be a specific budget for IT projects. How this money is allocated will depend on what the IT goals are. (Again, in a perfect world, IT goals are obtained from the business and reflect how IT can best support the business goals.)

The aforementioned discussion is a very academic and simplistic description of the governance structure in most organizations. It ignores one of the critical aspects of selecting projects—dealing with the internal politics.

While it is true that everyone in a management role cares about the long-term growth of the organization, in the short term, they care more about advancing their own small part of the organization, and in fact they get rewarded and promoted for doing so. Their emphasis is on their group (whatever the size) growing and advancing. In turn, this will lead to more responsibilities and greater advancement for themselves.

Why is this important to us? Because this structure often pits one manager or one group against another in competition for financial resources and projects. While most managers would acknowledge that all parts of the organization are important, each manager also feels that his or her part of the organization is more critical to the overall organization than other groups.

Story

In one California utility the author has dealt with, upper management realized rather late that the workforce in one Business Unit was entering retirement age (Note: for a normal organization, this is predictable years in advance. The executives simply didn’t think far enough ahead, so it came as a surprise to them that their workforce was getting older).

The executives decided to implement two solutions in parallel— the first was to install an ERP system (SAP) and the second was to perform an enterprise-wide business process integration (BPI) effort.

While everyone applauded the BPI effort, once it began, it progressed very, very slowly. While the business unit managers and general managers appreciated the need to improve processes, each process had a process owner whose ownership and power was threatened by the BPI effort. These process owners, all high-level managers, publicly supported the effort but privately did not cooperate at the level needed for success. They didn’t see the benefit to themselves, and in fact they were very protective of the business processes that they were in charge of.

From this inherent situation will come most of the resistance to implementing the EPMS and most of the difficulty in managing it. By taking away the ability of managers to make individual decisions on which projects to fund, the EPMS will take away some of their power and authority. Unless managers are sold on the benefits of the EPMS to themselves individually, they see no benefits to it, only downsides.

In this hierarchy from the bottom of the organization to the very top, where does portfolio management fit in?

Looking from strategy, to portfolio, to program, to project, and finally to operations, we can compare the focus of each of these, the alignment, the stakeholders, and the indicators as Abdollahyan20 has done:

Table 1.1 Focus of different stakeholders

|

Strategy |

Portfolio |

Program |

Project |

Operations |

Focus |

Mission, vision, and objectives |

Strategy delivery |

Outcomes, “benefits” |

Outputs, “deliverables” |

Sustained business |

Buzzword |

Strategy |

Strategic alignment |

Benefits realization |

Product and capability delivery |

Business-asusual |

Stakeholder |

Owners, shareholders, market |

C-level and middle management |

Sponsors, beneficiaries, and other stakeholders |

Sponsors, clients, users, and other stakeholders |

Management, clients, users, and other stakeholders |

Indicators |

Enterprise value indicators |

Portfolio value indicators |

Benefits and project performance indicators |

Project performance indicators |

Operational excellence indicators |

Abdollahyan’s use of the term buzzword may be understood as alignment.

This matrix shows how portfolio management fits into the overall framework of implementing strategy within the organization so that the day-to-day operations of the company support the long-term goals.

Step 1.4 Managements Goals and Expectations

Our ultimate goal is not to deliver an EPMS. That’s just the mechanism. Our goal is to deliver the information that management needs to decide on the best projects to deliver strategy. Our tool is to develop an EPMS that does that, to deliver a system that satisfies what management needs and that the participants will want to use. Does the last sentence sound like two different goals? They are not. They are in fact the same goal, but inexperienced project managers may lose sight of the distinction. You’re not just delivering technology and a new business process, you’re delivering a way for the entire organization to become more efficient and more effective. You are making a significant improvement in how the organization works. How much of an improvement? We will give you some numbers later, but you can tell your executive sponsor that a paper on effective portfolio management systems published by IDC21 shows that for the companies surveyed:

• Number of projects managed increased 35 percent

• Cost per project was reduced 37 percent

• Redundant projects dropped 78 percent

• IT staff productivity increased by 14 percent

• Project failure rate dropped 59 percent

• The total annual benefit per 100 users is $83,500

• Payback occurred in 7.4 months

• Return on investment was $5.57 for every $1 spent on portfolio management

PMI’s annual Pulse of the Profession (op cit.) showed the following drivers for portfolio management:

Figure 1.4-1 Portfolio drivers

Determining goals and expectations is the process of gathering the business needs for the EPM system. What is it that management expects from it? Why did they decide to do it? Are their expectations realistic? Did someone read a one-page article in a management journal on the benefits of portfolio management and decide this is what we need?

Story (Remember Windows 8?)

A survey of over 1200 people by TechRepublic22 showed that 74 percent of organizations have no plans to implement Windows 8. Considering the many millions of dollars Microsoft spent on developing the new OS and that much of their income derives from selling the OS, that’s a potentially huge hit to their future income.

Some selected quotes from the interviewees were:

“Nightmare waiting to happen in the corporate world. [The] Ul will be difficult to train people [on].”

“Win 8 is not suited for an enterprise due to the metro interface and pathetic dual screen support.”

“Windows 8 offers our laptop and desktop environment no compelling features. Pandering to tablets with [their] Ul did not go over well at [all].”

“The user interface is just too much of a change...I did a test demo [and the users] all hated it.”

“A reduction in productivity due to bad GUI design.”

What happened? How could such an expensive project return such poor early reviews?

Determining management’s expectations, both stated and unstated, is a major part of starting the effort. This part of the project is too often either forgotten entirely or done poorly. Too many nonproject managers think that spending time determining in detail what they need, determining the requirements, doesn’t seem like “real work”—you’re not planning the schedule, you’re not coding, you’re not meeting with vendors, you’re not testing. But, and let me emphasize this, everything else you do and the success of the project will depend on how thoroughly you understand what people need, want, and expect. Literally, everything else on the project is based on that. How well your requirements are determined and approved will dictate your project management approach

How do we measure whether we have been successful or not? The EPMS itself will use financial criteria as part of the decision criteria for approving a project, and a common financial filter is Return on Investment (ROI). ROI measures the financial returns from the money your company is spending on the project. It is a straightforward and very simple calculation, but every financial filter has limitations. A more sophisticated EPMS will compare ROI, Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Net Present Value (NPV) to select the projects that provide the greatest benefits.

But not all projects are susceptible to purely financial filters. Think about the traditional public works project—a new highway, a dam, or a bridge. How do you calculate the financial return on those? For these types of projects, the Benefit/Cost Analysis is typically used. While fruitful, the BCA is subject to a lot of assumptions and is highly inaccurate. Research by Flyvbjerg,23 for example, has shown that public works such as roads has a typical cost overrun of 20 percent and an overestimate of the benefits of almost 10 percent.

For projects such as the EPMS itself, sometimes a better calculations is Return on Expectations (ROE). This should answer the question whether the EPMS delivered what was expected.

Story

Let’s look at one success story in Portfolio Management—Chevron Oil Company (This material is based on a presentation given on 4 March, 2009, by Janinne Franke of Chevron’s IT department and is used with permission). They are developing advanced capabilities in IT portfolio management by having a thorough understanding of how it can benefit the business and centralizing portfolio management in a PMO (Portfolio Management Office) for each business unit. This is a journey that they’re still working on. It will take some years to achieve their goals.

In 2009, Chevron was the 6th largest company in the world by revenues with over 65,000 employees worldwide. Their IT group had over 6,900 people located in 64 locations around the world. Before they began a transformation of IT, the department was focused on their customer’s, the business unit’s, immediate needs. While this is normal for IT departments, it is a very tactical approach, not a strategic one. The end result is generally a patchwork of non-integrated systems, numerous incompatible applications, and no long term planning. Chevron’s goal was to transform the IT organization to focus on the best way to achieve long-term business strategies.

IT had five key focus areas:

1. Run and support Chevron’s IT assets securely, safely, reliably, and efficiently

2. Improve reliability, the transparency of IT spend, and our overall project planning, prioritization, and execution capabilities

3. Deliver the critical few IT Investment Strategy initiatives with excellence

4. Sustain the value of these investments through effective support and an improved ability to extract the intended value

5. Shape the 10-year vision and strategy, and set priorities for Information Technology at Chevron

The emphasis of the PMO was on the second focus area—improve reliability, the transparency of IT spend, and the overall project planning, prioritization, and execution capabilities. Although in addition, the third focus area involves identifying the critical few IT investment strategy initiatives is also a valid goal of portfolio management.

How were they going to achieve this? Their stated objective was to develop processes, tools, and analytics to enable, measure, and advise on the following areas:

• Balanced Portfolio: Balance projects according to the organization’s strategy and other parameters in order to achieve a desired return. Maximize the value of the Portfolio via key metrics while keeping an acceptable level of risk.

• Optimized Resources: Allocate resources to the highest value projects and ensure that resources are being appropriately utilized. Manage the “peaks and valleys” of resource use.

• High Value Work: Ensure that the Project Portfolio reflects the business strategy and that the breakdown of spending aligns with business priorities.

In order to achieve their ultimate goal of being a great business partner, beginning in 2005 they created processes for becoming first a great service provider, then a good business partner, then a great business partner. Each of these goals had a series of lower-level goals to accomplish. One of the ways to becoming a great service provider, their steps include understanding the business needs first, then achieving operational excellence, then managing their IT costs.

On their way to becoming a good business partner, the steps involved first understanding the business strategies, translating those strategies to clear credibility gaps, then finally aligning IT strategy, portfolio, and the enterprise architecture. It was in these steps that the portfolio management process was created and implemented.

Once this is achieved, they can use their portfolio management process to develop an IT strategy that’s integrated with and supports the business strategy. (This process puts the ownership of IT strategy on the business, where it properly belongs. It’s the business who should be driving IT’s strategy and let IT determine how best to achieve that strategy.)

As we will see later, a normal project selection process under a portfolio management system selects the projects that are most beneficial (usually using financial criteria) at an acceptable level of risk. For Chevron, their system includes financial calculations and risk assessments, but in addition, they filter projects for strategic fit:

Figure 1.4-2 Chevron’s IT goals

• Enterprise Strategic Fit—Support of strategy with emphasis on an enterprise-level view

• Business Unit Strategic Fit—Support to specific Business Unit level strategies

Because the oil/gas industry sector is highly-regulated, Chevron’s first filtering criteria is related to whether this is a compliance project or not. (Any regulated industry must use this filter as a first one before any other filters are utilized. We will look later at Toyota USA’s project selection criteria and see that they have the same one.)

There is no progress without measurement. You have to know where you are to understand whether you have improved or not. Chevron developed a 5-tier maturity model similar to that developed by the Software Engineering Institute’s Capability Maturity Model (CMM). They defined four areas of competency (Strategy, Process, Tools/Technology, and Organizational Capability) and measure these across five levels of maturity:

as shown here:

Figure 1.4-3 5-Level hierarchy of maturity

Not all of Chevron’s business units aspired to be at level five on all competency levels. Some are happy to stop at level three (shown by the sun between levels 2 and 3), which would be the minimum rating of an impactful Portfolio Management Office. Any level lower than that would move the PMO to a project management office.

The end result of an effective PMO is enhancing business values in:

Planning

• Enhanced partnership between Business and IT enables business strategy

• Objective project selection and prioritization based on business drivers

• Balanced Project Portfolio mix to maximize return

• Comprehensive data enables improved decision making around resource allocation and portfolio investment

• Relationship visibility between all projects, programs and portfolios and alignment to business strategy

• Reduction of disparate Portfolio Management tools

• Reduce number of projects by understanding cross-functional synergies/overlaps/redundancies

Execution

• Greater agility to respond to changes in business conditions decreases time-to-market

• Improved On Time On Budget performance through enhanced project planning capability

• Reduced cycle times through improved and standardized Portfolio Management processes

• Productivity gains through increased automation and process refinement

• Cost avoidance and reduction of project delays by more proactive resource planning and optimization

• Maximize the efficient use of resources and assets with an emphasis on safety and reliability

Realization

• Centralized Project and Program data enables improved decision quality through portfolio analytics

• Ability to monitor progress through measured attributes and KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) against business objectives

• Application of industry performance benchmarks

• More control for continuous improvement

While other approaches are possible, the one Chevron is using is very well thought out and well planned. Did they achieve their goals? By 2014, they had achieved Level 4 and were part of the way into Level 5. According to stock analysts Chevron is one of the best managed major oil companies.

The stepped development process is highly recommended for implementing a major change such as implementing an EPMS. The Mayo Clinic24 used exactly the same incremental approach to delivering benefits as shown in the following figure:

Figure 1.4-4 Mayo clinic’s hierarchy of benefits delivery

We will talk in some detail later about supporting the strategic goals of the organization, but do you know what they are? Sometimes they’re described in the Vision and Mission statements that are commonly published in the organization’s annual SEC filing of their annual report (for publicly held companies) or in some other high-level document. But any large organization can have multiple strategies.

Let’s look at one well-known worldwide organization, Pepsi Cola. They have a product strategy, a marketing strategy, an advertising strategy, an environmental strategy, and other strategies. And these are not only for the overall corporate organization, these also exist for each company in the Pepsi family. There are multiple drinks, “convenience” foods, cereals, cookies, and other product companies within the family, all having their own strategic goals and plans, which are subsidiary to the top-level organizations. So strategic goals really mean the specific long-term goals at the level of the organization you are developing the EPMS for.

Sometimes the long-term goals can be very tactical instead of strategic. For example, look at the car industry during the recent economic downturns. Instead of planning for 5 to 7 years of growth and advancement, the major U.S. car manufacturers were planning for survival and cost savings. General Motors,25 as an example, was looking in 2009 at:

• Cut its North American nameplate lineup from 48 down to 36 by 2012. Hummer, Saab, and Saturn will account for most of those cuts.

• Reduce workforce by 47,000 globally, including 10,000 white collar (3,400 U.S. white collar)

• Close 14 North American factories by 2012, five more than in the December 2 plan

• Reduce U.S. dealers from 6,200 currently to 4,700 in 2012 and 4,100 in 2014

• Seek to convert bondholder debt and funding to autoworkers’ retirement health care funds into GM stock

Each one of these efforts is a project, a big one, and will consume a lot of time, effort, and resources. You can very easily build an EPMS at the corporate level of GM just to handle these types of projects.

1.5 The Business Case

After you have done the initial work to research the benefits of an EPMS and have sold the idea to the upper echelons of the organization, you have to get their formal approval for the effort. It’s time to write the business case and get blessing by the upper levels of the organization to start the project. This has to be done prior to interviewing the decision makers on exactly what they want out of it, de-conflicting their needs, researching ways to properly prepare the organization for the coming changes, and do all the other prep work, you still have to get formal approval to design, develop, and implement it.

What is a business case? It’s a written justification that convinces upper management that this project should be done. Right now, it is how you will show the benefits (emphasizing the financial benefits) of the EPMS. In the future, it will be a major input to the project selection process. It provides the benefits of the project to the organization, the costs of the project, and the risks associated with it. A major part of the business case is the financial justifications that we discussed in the previous section. Your business case is used to “sell” the project to the decision makers.

Competent high level decision makers don’t make most major decisions based on their gut feelings. At the top of the organization, their primary interests lie in moving the entire organization toward its strategic goals. They need numbers that show the benefits, and the more you can justify the numbers, the more convincing your argument will be.

During periods of economic growth, executives are more willing to spend money to grow the company. There’s a feeling of “we can do even more” and a desire to get bigger. During periods of economic downturn, it would seem rational that the executives would be more willing to authorize work that reduces costs or to improve productivity. Unfortunately, the opposite is usually what happens. They become more reluctant to spend money no matter how good the long-term payoff is and so the justification needs to be even better. Hint: Get someone from the marketing department to help you gather the information needed here and to help you write it. Marketing people are, as a rule, better at communicating these areas than technical people are. They’ve been doing it a lot longer.

Executives need hard numbers. The kind you find in a business case justification. So what goes into the business case? There are many different templates for business cases depending on the type of project. Exactly what goes into the document depends on the type of project and in what your management wants to see. A business template for an IT project would be very different than that from a pharmaceutical development project or for a new factory. The organizations that have the most detailed business case templates are government organizations because of the heavy oversight of government projects and the probability of an audit if the project runs into trouble. So, there is strong emphasis placed on justifying the project. Some of the best templates available are freely downloadable from government websites.

A business case is designed to provide financial justification of the proposed spending initiative (which in our case is a project to implement an EPMS) as well as its risks. While most organizations have its own internal template for one as we have just seen, normal sections include the sections necessary to “sell” the project to upper management:

• An Executive Summary

• A description of the current situation—the business need

• Project Benefits—how does the project fit into the strategic plan?

• Description of the Solution

• High-Level Objectives

• Competitive Position (not necessary for an internal project such as this)

• Impacts to the organization and on-going work

• Potential Risks

• Assumptions

• Alternatives

• Financial Costs and Benefits

Experienced project managers will recognize a lot of these sections. They are commonly documented in the project charter. The differences are the emphasis on the business benefits so we include some competitive analysis and ROI calculations. Sometimes the business case is appended to the project charter. Oftentimes the business case substitutes for the project charter. If you already have a business case, there is very little that needs to be added to it to make it a proper project charter. If you develop a separate project charter, at the very least, attach the success criteria and the financial justification from the business case.

1.5.1 Executive Summary

This is a short summarization of the rest of the document. It emphasizes the benefits, costs, and risks. Most of the executives will read the summary, make a decision, and browse the rest of the document to reinforce their decision. This should be the last section written but it must be the most well written. The project is highly likely to be approved or rejected on how well the executive summary sells it.

Why are we doing this? What’s the problem, the pain, that’s causing us to develop an EPMS? Or what’s the benefit of doing so? If there’s no real problem, why should we approve this?

This section must be written so that the decision makers see the problems that not having an EPMS causes. Typical problems that occur by not having an EPMS may include:

• Duplicated work and waste because there are multiple projects trying to do the same thing

• Time-to-profit for new products is poor because of the long timelines involved in developing new products

• Projects continue even though the reasons for them have disappeared, wasting time, and money

• Managers are approving projects that benefit their own part of the organization instead of the overall organization, leading to suboptimal use of scarce resources

• Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera ad nauseum

The more you can convince people there are significant problems the EPMS can solve, the more likely you are to get it approved. If you can put financial numbers around the preceding items showing how much productivity is lost or how much money is wasted, you will significantly improve your chances of getting approved even in a downsizing economy.

1.5.3 Product Overview

Here’s where you describe what the EPMS will look like, and how it will operate, once it’s implemented and integrated into the overall organization.

1.5.4 High-Level Objectives

High-level objectives for the EPMS should be the solution to the problems described in the section on the current situation and they should be quantifiable to the extent possible. For example:

• Increase productivity of the IT department by 10 percent by killing duplicate projects

• Reduce time-to-profit for new product development by 6 months

• Select more projects that support strategic rather than departmental objectives

• And so on

Remember our goal—to implement a system that will significantly improve how the organizations selects projects and moves toward its strategic goals. The more you can make that goal specific and measurable, the better your chances of getting the project approved. The PMO the author created at the car company mentioned earlier reduced the time required to approve new projects from 6 months to 3 weeks. That’s the kind of benefit that convinces management this is a good thing to do.

1.5.5 Competitive Position

Typically not required for an internal business process change such as implementing an EPMS.

1.5.6 Impacts

This section describes the impacts to the on-going work in the organization. What are the impacts to operations? What are the impacts to existing projects? How many people will be pulled away from their normal daily work, and for how long?

Here’s where your writing must phrase things very carefully. There will be negative impacts, especially in the short term. You will need to have people working on the project who are doing other work and will need to be pulled off it. You will likely be disrupting other projects in work. Mid-level managers will be reluctant to loan their best people to a project that is going to be disruptive.

Once the EMPS is implemented, it will look first at the existing projects in the organization and identify any overlapping projects, duplicate projects, and projects that need to be killed. Once project managers and team members hear you are going to do that, they will either stop working on projects that, in their minds, are likely to be cancelled or they will protest vigorously to protect their projects. So there will be impacts to doing the EMPS, but it must be emphasized in the business case that the negative impacts are short term and that the organization will be much better off in the long term.

1.5.7 Potential Risks

Every project has risks. This one is no exception.

What is a risk? A risk is anything that can happen in the future that will impact the success of your project.

In this section, you capture the risks you know about at this point. Have a tight schedule? That’s a risk. Don’t have dedicated resources to implement the EMPS? That’s a risk. Because implementing a major organizational process change like you’re doing impacts how people work? You will face a lot of organizational and political risks also. We’ll cover risks more thoroughly in the next chapter.

1.5.8 Assumptions

An assumption is anything you expect to be true for planning purposes. If you think you’ll have enough dedicated resources to do the work, that’s an assumption. If you think this project will have interference from managers in other departments, that’s an assumption. If you plan out the project expecting that software and hardware prices will not change in the future, that’s an assumption.

Your entire plan—schedule, budget, deliverables, is based on assumptions. The more of these assumptions you can define and document, the better your planning processes will be. Determine what your assumptions are so that you can understand better the weak points in the plans. But for the business case, just write down the major, high-level assumptions that management can understand.

One statement that is always true in planning projects—any assumption becomes a risk if it turns out not to be true. There’s an inverse relationship between risks and assumptions. If you assumed you would have a highly skilled data base analyst (DBA) to design your data base, and later find out there is none available, now you have a risk.

1.5.9 Alternatives

A section of alternative solutions to the stated problems is a common one in the business case. What other ways are there to solve the problems stated in the Current Situation? Are there simpler solutions? Is there something less costly or less disruptive that we can do instead? Because you have been thinking so much about the portfolio management solution that you have become focused on it; you should get inputs from other people to help write this who are less tied to a single solution.

Of course, one solution is always to do nothing. This is the default solution. If upper management isn’t feeling enough pain from the problems or if you haven’t convinced them of the benefits of this project, this is the solution they will often pick—to do nothing and to keep the status quo as it is. Even a bad status quo has more supporters than people willing to change.

We can avoid reality, but we cannot avoid the consequences of avoiding reality.

—Ayn Rand

1.5.10 Financial Costs and Benefits

This is the crux of the business case. Here is where you justify the benefits of implementing the EPMS. The emphasis of this part of the business case will be hard numbers, the more detailed the numbers, the better. Because this is your best guess, plus or minus 20 percent variation is normal.

For most projects, it is easier to identify the costs than it is the benefits. We can estimate the size of the project, the resources we’ll need, and any expected expenditures and develop reasonable rough numbers for the costs.

It is much harder to come up with valid numbers for the benefits. There are always a lot of loose assumptions in defining the benefits of a project. Do we expect an increase in market share because of what this project will provide? How much? 5 percent market share increase? 10 percent? 2 percent? Do we expect to increase the productivity of the IT department by implementing an EPMS? If so, how much? A 2 percent increase in productivity for 250 people is a significant improvement. But where did you come up with that 2 percent number? It’s an assumption on your part at this point unless you can show how you calculated that. Hubbard’s book “How to Measure Anything” discusses the difficulties in detail.26

Total Costs of Ownership include any on-going licensing and maintenance fees for software and hardware and the operating costs once the EPMS is in use. Typically, these life-cycle costs would be calculated out for a period of 3 to 5 years. Your financial people will tell you what the planning horizon is for financial calculations. The greatest benefits from an EPMS come in the future. If you just calculate the cost of the EMPS implementation itself you will not have the opportunity to show the benefits.

Whatever numbers you come up with, be prepared to justify them and show that they are reasonable approximations. Management is used to reading a business case that has best-guess estimates in it, but you should have the backing for what you put down.

For the majority of projects, the benefits will be financial—Return on Investment, New Present Value, Internal Rate of Return, payback period, and so on. This is a valid justification because an organization is not going to spend money and resources on something that will not provide a positive payback.

As we will see later, some projects are mandatory. Regulatory-driven projects, required maintenance projects, and others. For these projects, the financial justifications are almost irrelevant. Management will approve these projects because they must, not because there is a financial benefit to doing them. So when we are using the EPMS to identify these projects, don’t spend much time on the financial benefits, just capture the costs.

Because the EPMS itself will perform financial calculations once it’s in place, we discuss how to do this in great detail in the next chapter.

Step 1.6 Organizational Change Management (OCM)