The focus of this chapter is growing capability by delegating meaningful tasks and learning to let go.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

Hands up all of you who don’t have enough to do. We guess that not many hands went up. In fact, most of you probably have far too much to do, feel stressed that you can’t keep up with all the demands on your time and seldom leave the office at the appointed hour.

We believe that if you did an honest audit of how you spend your time, you would find that about a third is spent doing tasks that you really shouldn’t be doing and about another third is spent in meetings where you make little or no contribution. All of this means that, on average, only about a third of your available time is spent doing meaningful things that might actually produce value for your organisation or develop the people under your care. Let’s look in a little more detail at the first two categories.

So why do you spend time doing things that don’t necessarily need to be done by you? There are a number of reasons. Maybe they are things you were good at before you got promoted and you feel that you do them best or perhaps you just like doing them. Alternatively, you may feel that you are the only person that will do the job ‘right’. You could say that the time that you spend doing all of the above represents your potential energy, time that you could free up in order to do something more beneficial for your organisation.

Now let’s look at the third of your time that you spend in meetings or dealing with organisational noise that has little or no relevance to your day job. This includes drafting long and complicated responses to emails on which you were just a ‘cc’ addressee, and attending meetings where you have no useful input but you feel that your organisational position demands that you are seen to be present, or just the fear of missing out (FOMO). Generally, we find that this sort of frantic organisational arm-waving depletes your time and energy, but usually fails to produce anything in the way of valuable organisational results. You could say that this represents your kinetic energy, energy that you could redirect towards more purposeful ends.

The chances are that you have considerable stores of untapped potential and kinetic energy. The scientists among you will know that you cannot create new energy, but you can certainly redirect the energy that you have. The good news is that the number-one way of redirecting your energy as a manager is the art of delegation.

THE IMPACT OF THE ISSUE

All leaders have a duty to develop their people, so that they can achieve their full potential and, in so doing, contribute to the broader business success. This element of the leader’s role is a form of organisational stewardship that requires a level of selflessness and a willingness to see the key role of management as developing people. Alas, in our experience, we find that many leaders strike the wrong balance between task and people focus. It may be that they have had little exposure to people management skills in their education and have achieved their position as a result of excellent performance in their technical specialism. But, as a leader, your organisational value lies not in what you can do, but, rather, in what you can enable others to do; this is rooted in your ability to delegate.

Leaders who fail to delegate, or who delegate poorly, are failing their organisation and failing in a duty of care to their people. Failure to delegate appropriately will lead to:

•

people not realising their talents and underperforming;

•

people not knowing what they are supposed to be doing;

•

people working at cross purposes or in general confusion;

•

missed deadlines, increased stress and burn-out;

•

a vacuum when you need to move on and no one has the skills to succeed you. Indeed, one of the biggest issues that organisations face at all levels of leadership is succession.

MAKING SENSE OF IT ALL

Delegation is about giving up part of your job with the two prime objectives of: growing the people who report to you; creating space in your own diary, so that your own boss can grow you by delegating part of their job to you.

If these are not your objectives, you will be effectively ‘dumping’ or ‘offloading’; and just as you don’t like to be dumped on, it is not nice to do it to others.

Delegation is really important; you have to find a way to do it and make it work for you and your people. Understanding why managers avoid delegation is the first step towards developing your own coping strategies.

There are three principal psychological barriers to delegation:

•

It often involves giving up jobs that you like doing – this is the difference between being efficient and being effective. You write code efficiently, but being effective is about directing your efforts to the right job.

•

It usually involves overcoming the fear of losing control – people often think (sometimes rightly) that nobody else can do the job as well as they can. Therefore, when you give a task to someone, you then unfairly judge the quality of what they produce and often end up redoing all or part of it to your own exacting standards – this creates needless extra work and stress that could have been avoided.

•

There is a need to balance two, potentially competing, psychological contracts – one with your own leadership or customer who wants the outcome of your delegated task, and one with the person you delegated to who is looking to you for help and development. These contracts tend to be implicit, rather than explicit, and leaders are often lax at making sure that everyone’s expectations are aligned.

In addition to the psychological barriers, there is also the practical barrier that delegation takes time and effort. You need to select the right person, brief them properly, spend extra time guiding their efforts and reviewing their progress, and, finally, you need to check their output. This all takes time and, unless you create the time and space to do it properly, the chances are that your delegation process will just end in frustration and confusion.

When you delegate a task, you need to take full responsibility for ensuring that all parties have total clarity about what is expected and how the quality and usefulness of the output will be judged. But this is not a ‘one size fits all’ process. Each person has differing levels of ability, willingness and desire to engage and each person has differing levels of confidence and processes information in different ways. (See practical advice later in this chapter.)

Even when you manage to overcome the psychological and practical barriers that stop most leaders from delegating, you are still faced with the issue of organisational responsibility. You need to remember that you can delegate tasks and the authority to do those tasks, but you cannot delegate accountability. You are the leader; if it all goes wrong you are accountable because you have managed unwisely. Pointing downwards and claiming ‘the dumb cluck let me down’ is just another way of saying ‘I’m a useless leader who doesn’t know what I am doing and can’t see what is happening around me’.

So now let’s look at some things that you can start to do now that will help you overcome all the barriers and become great at the art of delegation.

When you come to delegate there are some golden rules that should guide you regardless of who you are dealing with or the nature of the task. You should always:

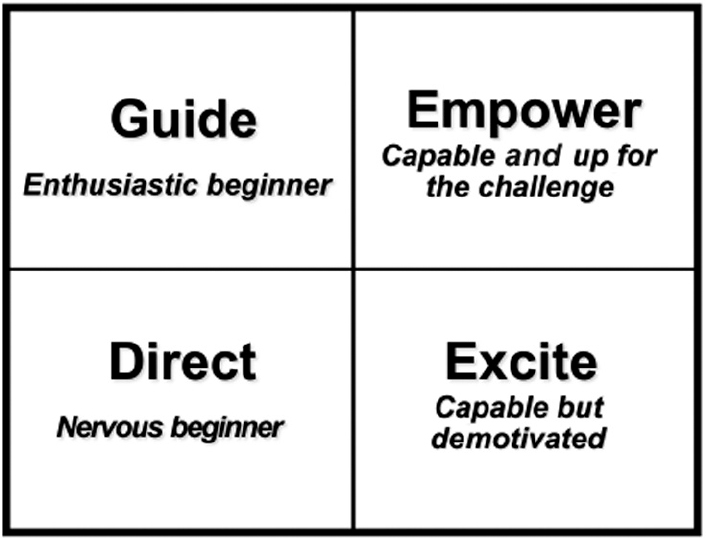

Who you delegate to is just as important as how you delegate. You need to be careful that your chosen person has not only the skills and knowledge, but also the desire to take on the task. Not every task can, or should, be delegated and not everyone is ready to be delegated to. Figure 3.1 sets out four different options for intervention based upon an assessment of both the individual’s knowledge and ability to complete the task and willingness or motivation to do so.

Figure 3.1 Four modes of intervention1

Looking in depth at the four quadrants you can see that you need to tailor your approach very significantly if you are to get the best out of people.

Direct – these are people with low levels of skill and experience who are not used to taking on additional responsibility. If you delegate to these people, you should start with relatively straightforward, well-bounded tasks that are likely to recur soon, so that they can get additional practice at the same sort of activity. You will need to:

•

tell them what to do and provide a step-by-step guide on how to do it;

•

check their understanding;

•

provide clear rules and deadlines;

•

give them just enough training as they are about to take on the task;

•

provide frequent feedback against progress;

•

supervise closely – praise and nurture.

Guide – these people are ready and eager for the challenge, but don’t have the skills and knowledge required to perform well. They probably don’t realise how little they know and, in their eagerness, are likely to charge into things and often make mistakes: mistakes that they may not recognise. They still need lots of direction, but you will need to be subtle about how you do it as they tend to be impatient:

•

Explain what you need them to do and suggest in broad terms how they may go about it. Suggest they bring back a detailed plan of action before they start work.

•

Check their plan and confirm their understanding of what outcomes need to be produced.

•

Check their understanding by asking them to think through what might go wrong and where they may need help.

•

Identify people they can talk to who have done something similar.

•

Monitor, provide feedback and praise.

•

Control without demotivating, and relax the frequency and depth of your controls as progress is made.

Excite – these people are well able to do the required task, but are reluctant to step up to the plate. They may have had a previous bad experience or may not have learned to trust you. Managers often ignore, or sideline, this sort of person as being too difficult. These are key resources and need to be engaged for their benefit and the benefit of the team. You will need to:

•

Explain what needs to be achieved and why they are well suited to the task.

•

Spend time with them to identify the reasons for their reluctance. Is it a question of your management style or some previous bad experience or some other personal factors?

•

Energise and engage them – use them as a sounding board for ideas, show that you value their input, and include them in scoping the task and defining the outputs and quality criteria to be used.

•

Develop a coaching relationship with the objective of their personal growth. Remember that the relationship between coach and coachee must be elective and trust based. You may be their manager, but you may not be the best person to coach them.

•

Monitor and provide frequent feedback and praise.

•

Ensure that they get wider recognition for their efforts – involve them in presentations to clients or senior leaders. Sing their praises to the rest of the team.

Empower – these people are ready and eager for the challenge; if you don’t harness their energy, they will probably find a way to go around you. These are candidates for your succession planning. You should go beyond just delegating tasks to these people – you need to delegate decision making, as this is a key management skill. With these people you need to:

•

Talk about the desired outcomes and ask them how they would achieve them.

•

Use analytical and explorative questions to check that they have considered every angle in relation to the problem or opportunity.

•

Involve them in decision making and the identification of additional resources.

•

Give them responsibility for getting other people up to speed and provide the necessary training.

•

Adopt a coaching style in order to grow your ‘star performer’.

•

Look for opportunities to praise and encourage, don’t ignore or over-manage them.

•

Celebrate their successes.

THINGS FOR YOU TO WORK ON NOW

Delegation must be a purposeful activity done in a thoughtful way. Don’t wait for a crisis, an emergency or a deadline to prompt you to delegate activities; in such circumstances you will not be in the right state of mind to delegate effectively.

Below are some questions to ask yourself to help you adopt a more structured approach to delegation that benefits your staff and helps you at the same time.

The above questions will give you some insight into who you need to develop and what you need to focus upon. Below are some practical tools that can help you plan your approach and monitor your own progress.

FURTHER FOOD FOR THE CURIOUS

Harvard Business Essentials (2005) Delegation: Gaining time for yourself. In: Time Management: Increase your personal productivity and effectiveness. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. 63–76:

•

This is a good primer that links the related arts of delegation and time management, and provides practical tips and advice.

Keller Johnson L. (2007) Are You Delegating So it Sticks? Harvard Business Review, September. Available from https://hbr.org/product/update-classic-are-you-delegating-so-it-sticks/U0709B-PDF-ENG [21 March 2017]:

•

This short paper sets out five big ideas to help you become more effective in delegation.

The concept that different people need different styles of intervention was developed by Hersey and Blanchard in their situational leadership theory and this idea was further adapted and enhanced into the skill versus will matrix by Max Landsberg in his book The Tao of Coaching: Boost your effectiveness at work by inspiring and developing those around you, first published by Harper Collins in 1996.