5

DIGITAL CRAFT

DIGITAL CRAFT

The introduction of new technology in the 21st century is impacting on many different areas of our lives and is developing at such a rapid pace that it is sometimes difficult to keep up. For the “digital generation,” technology has become second nature. For the designer rooted in traditional processes, technology is no longer possible to ignore. Some designers see it as a challenge to introduce new digital methods into their work, while others are fiercely protective of their tradition and craft.

This chapter looks at whether it is possible for a designer to maintain the “hand” quality of their work while using new technology. The first part of the chapter, “Combining old and new,” looks at how designers are finding ways to reintroduce traditional handcrafting skills into their work. The second part, “Desktop digital textiles,” examines how designers are taking advantage of the immediacy and hands-on approach of desktop printing to create a new craft tradition. Should the new skills that are being developed with digital design and print be recognized as a new craft skill, rather than just a mechanical process? This is for you to judge. But the potential for creativity using new technology is clear from the wealth of work shown in this chapter.

COMBINING OLD AND NEW

Working in a virtual environment with a mechanical output seems to make the creator keenly aware that the personal identity of the work is in danger of being lost. There is also a need for a textile designer to have a physical relationship with the cloth and this can become even more apparent when working in a digital environment.

Many designers are disappointed with the “flat” outcome of a digital print; the surface and tactile qualities created by traditional print methods are often lost. For some it seems too easy to print at the press of a button without physical effort, and the speed of the digital print process almost seems to compel the practitioner to work extensively on a fabric to slow down the process. The result is that some designers are now finding ways to put back these tactile qualities into the creation of fabric, and into the fabric itself by physical intervention such as over-printing and embellishment.

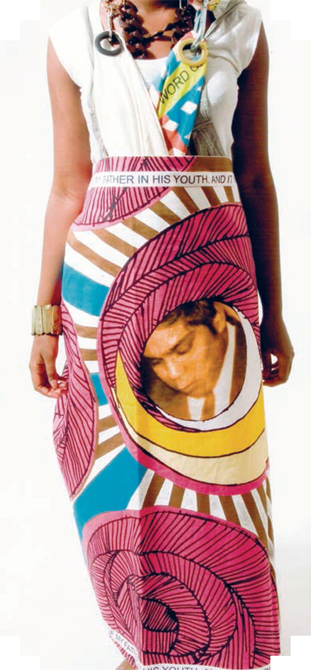

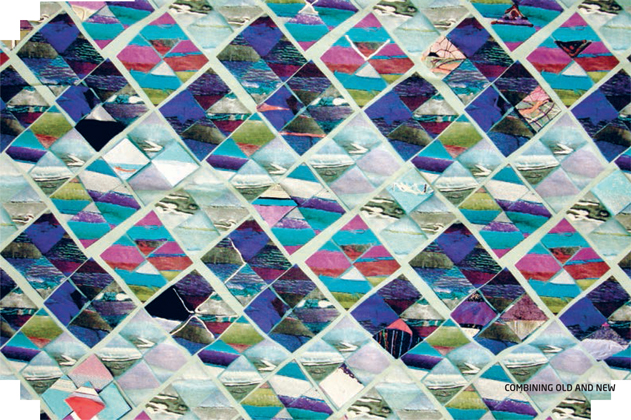

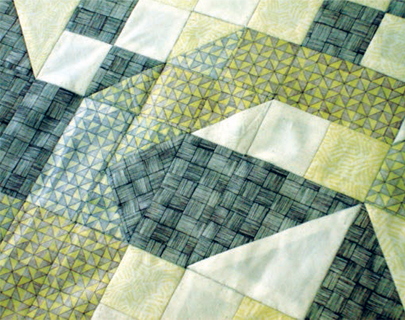

Clara Vuletich scans vintage patchwork pieces and digitally prints them onto cotton/hemp, thereby preserving and enhancing heirloom textiles.

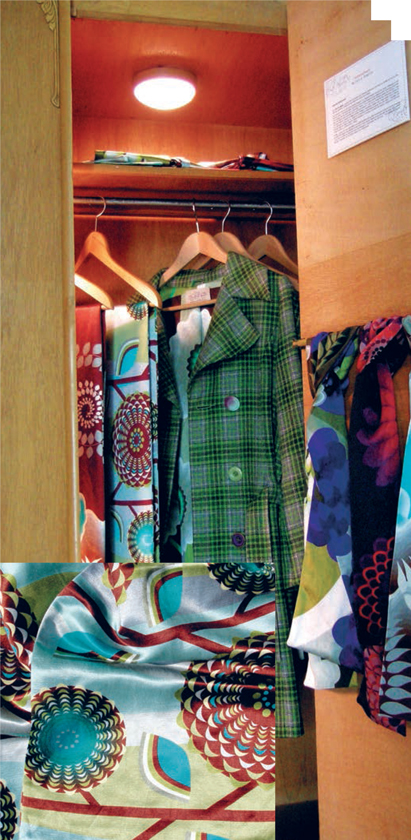

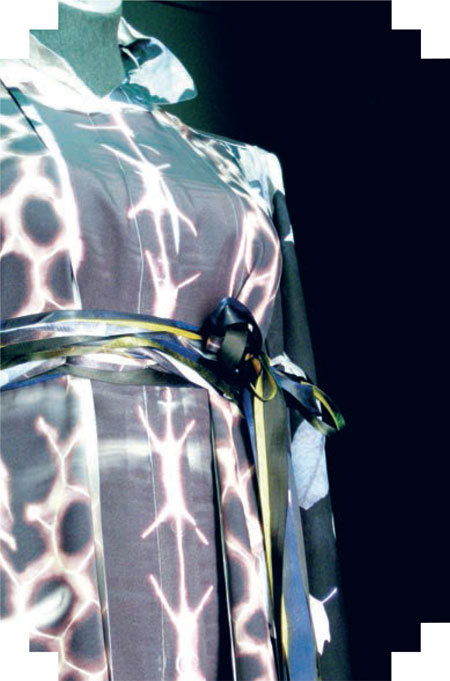

Collaged digital prints integrated into a Burberry jacket by Claire Canning.

Digital printing can appear flat, but once the fabric is made into a garment, it can come to life again. Claire Canning experiments with a combination of traditional screen-printing and digital techniques, adding depth by layering, collaging, bonding, and cutting. The rich photographic qualities that can be achieved with digital print give a playful, storybook narrative to Claire’s work.

For her conceptual blouse “Found by the Sea” (2009), Shelly Goldsmith used dye sublimation to emboss pressed plant samples from London’s Natural History Museum Herbarium on a reclaimed garment interior.

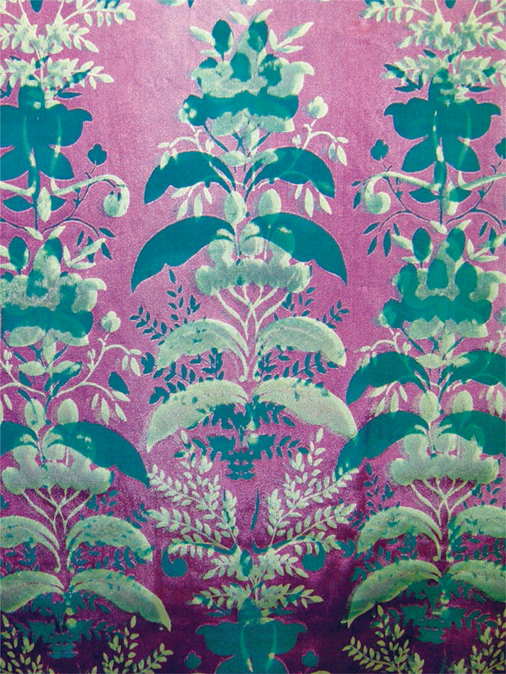

Melanie Bowles and Sarah Dennis created “The Wallpaper Dress” by scanning and then digitally printing a sample of vintage wallpaper onto linen, which they then embellished with embroidery.

Dominique Devaux creates rich digital prints inspired by her love of jewelry and antiques. She adds metallic foiling to give them texture and light.

This chapter looks at a range of techniques that can be combined with digital print to re-engage the designer with the cloth, in order to create beautiful and innovative surfaces. These range from screen-print methods, such as devoré, discharge printing, flocking, foiling, and laminating, through dye techniques such as shibori, to fabric manipulation, embellishment, and embroidery. Many of these techniques have, until recently, only been explored by couturiers, fashion designers, and textile artists due to the cost of digital print.

However, now that many established art institutions have a digital textile print facility, there is a wealth of experimental textile work emerging from colleges and universities, and professional, small-scale designers are also taking up this newly emerging craft. Much of this work is very experimental and in its early stages of development, but the examples here show the rich effects that can be achieved.

HAND PAINTING AND DIGITAL PRINT

Hand painting or drawing onto fabric is the most immediate method of adding depth to a digital print. Because of its simplicity this technique is sometimes ignored, but its spontaneity can complement the mechanical process of digital printing and also make a design much more personal. There are many fabric pens available that can produce a very good effect, including glitter, pearlized, and puff pens.

Zoe Barker scans her beautiful floral paintings and then prints them digitally onto silk. She paints into the fabric by hand to add an extra layer to her work.

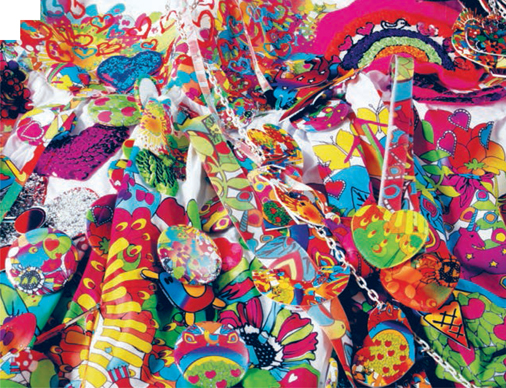

Dominique Devaux’s collection “Exotic Paradise” is based on her love of exotic birds and florals and inspired by childhood memories of the Caribbean. Dominique has embellished the fabrics with hand-painted foil glitter, creating light and reflection and bringing the digital print to life. Bands of brightly colored silks give a contemporary and exotic appeal, and the juxtaposition of real jewelry, sewn over photographic images of the same jewelry, adds another layer. The result is a highly effective, sensitive, and sensual approach to digital design.

SCREEN PRINTING AND DIGITAL PRINT

Screen printing is a fast method of combining digital prints and traditional print techniques; color is positioned in a design using screens. There are several chemical recipes for silk screening, and the most suitable ones for combining with digital print are: pigment printing, devoré, discharge printing, and the application of adhesive for flocking and foiling. The screen print has to work not only in harmony with the design, but also within the limitations of the fabric and print quality. Achieving the desired results can require much testing, and you will need a good knowledge of print techniques and an awareness of the health and safety issues involved.

Here, Emamoke Ukeleghe digitally printed a design of text with a hand-drawn pattern onto cotton satin, and then used a screen-print method to overprint with peach pigment.

As a designer, Ukeleghe crosses between the textile traditions of Nigeria and East London, merging digital techniques with traditional techniques to create a fusion between old and modern, ethnic and Western. In the bag on the right, entitled “Purpose, Wisdom and Enlightenment,” she digitally printed stripes onto cotton drill and then overprinted broken stripes in peach. In the bag on the left, “Laces,” she made a large-scale drawing of shoelaces with black ballpoint pen, and then digitally printed the drawing onto cotton.

In her powerful textile collection “Belonging(s),” Ukeleghe uses digital print combined with pigment screen-printing. Her inspiration came from issues surrounding displacement, and each piece tells a personal story. Here, a circular pattern was digitally printed onto cotton satin then overprinted with blue and white pigments. By including a photograph of a family member, she integrates a personal memory into her work.

DEVORÉ AND DIGITAL PRINT

In devoré printing, a chemical paste is applied to a blended cellulose-protein fabric. When heat is applied, the paste burns away one of the fiber types to leave a transparent area. Many digital print bureaus supply pretreated fabric specifically for the devoré process, such as silk/viscose satin and silk/viscose velvet. The chemical paste is applied to the fabric, either by hand or by screen printing, in the areas that are to be burned away. This can be done after digital printing has taken place. A heat process is then used to burn away the pattern areas to reveal a sheer, translucent area of fabric. The devoré process is time consuming and labor intensive, but the results can be beautiful. It should be approached with caution, and health and safely guidelines followed, as strong chemicals are used in the process.

Once the fabric has been put through the devoré process, the base color of the fabric is revealed. This area can be cross-dyed to reintroduce color into the cloth. Cross-dyeing works well with the devoré process as it stands out on the fiber that has not been burned away. If you used a screen to apply the devoré paste, you can use the same screen to apply the cross-dye.

Louisa-Claire Fernandes’s dramatic furnishings collection, “Simplexity,” combines digital and screen-printing techniques. First she created a digital print that became a background on which she applied other techniques. A large-scale devoré print gave her work a luxurious quality, and the dip-dyed effect was created by scanning in hand-painted papers. Her work demonstrates the combining of mechanical and hand processes to create a “new fabric” couturefurnishing collection.

Devoré paste has been silkscreened onto the digital print. Once the paste is dry, heat can be applied with an iron or heat press to burn out the viscose and leave the silk.

Here, Louisa-Claire Fernandes digitally printed a large-scale design onto a silk/viscose mixed fabric. The devoré area was cross-dyed in turquoise.

FOILING AND FLOCKING WITH DIGITAL PRINT

Foiling and flocking onto a digital print are popular choices for highlighting and embellishing designs. They are not as risky as the more experimental processes such as devoré and discharge printing, which are time consuming and complicated. Foiling can give highlights and added sparkle to a fabric, especially when the fabric moves. Flocking gives a beautiful raised texture to the surface of a fabric, which is often lacking with digital printing.

Metallic foils come in a variety of jewel colors as well as metallic effects such as copper, gold, and silver, and can be bought in sheet form from craft suppliers. Iridescent and holographic foils are also available.

In foiling, water-based or solvent adhesive is either applied through a screen or hand-painted onto the fabric. A sheet of foil is then stuck onto the adhesive. Heat is applied with an iron or heat press and, once the foil has cooled, the sheet is peeled back to leave behind a foiled area.

Small areas of foiling can be added to a digital print to highlight areas and make them glitter. You can also use a clear “foil” to create matte and shiny areas on a fabric that catch the light when the fabric moves. Carefully consider where to apply the foil so that the design and the foiling effect work together.

The raised, “velvet” effect of flocking is traditionally associated with decorative wallpapers. However, it is also suitable for fashion fabrics and can add a luxurious surface to the cloth. Flock can be purchased on a roll, attached to a backing paper. It is usually supplied in white, but it may be hand-colored with dyes. Flocking paper can be digitally printed on a Mimaki digital printer and then applied to a fabric, but this is still an experimental process.

Similar to the foiling process, the flocking paper is placed (flock-side down) onto a glued area. Heat is applied using an iron or a heat press and, once cool, the backing paper is peeled back to reveal the flocked area.

Amelia Mullins applied bold areas of gold foiling to complement her digitally printed silk dress.

Charlotte Arnold creates intriguing surface effects by applying digital flocking onto digitally printed silk. The result is a “new” looking fabric with a mixture of photographic imagery, light, and texture.

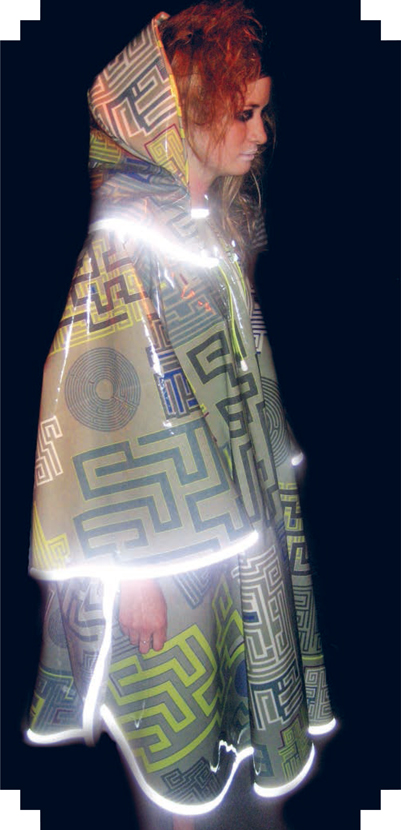

Emily House’s “Plastic Maze” was digitally printed onto cotton poplin and then plastic-laminated and edged with a reflective trim.

Matthew Williamson’s S/S 05 collection features this “Rainbow Dress” of digitally printed chiffon embellished with metallic foil.

Georgina Papandreou applied foil to her geometric digital print for a fractured, 3-D lighting effect that interplays with both the printed design and the surface of the fabric, creating a rich texture.

RICHARD WESTON

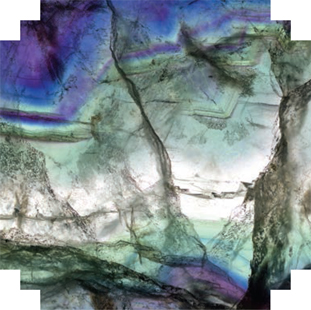

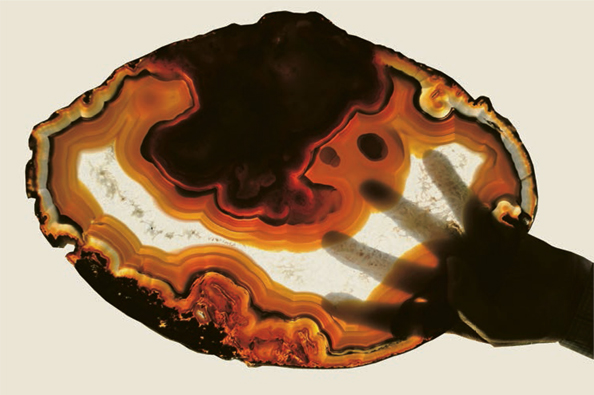

The writer and architect Richard Weston, Professor of Architecture at Cardiff University, Wales, came to digital textile design through his passion for collecting beautiful precious stones, minerals, and fossils. Scanning in his mineral collection at high resolution, Weston was able to capture remarkable patterns and colors. “The way the color works in these minerals is partly pigment and partly optical effect, so the absorption and reflection patterns are very different. You can get two scans from the same stone and you wouldn’t believe they were from the same mineral.” Enlarging the scanned images and “cleaning them up” in Photoshop enhanced and magnified the original natural forms.

A friend told Weston it would be possible to digitally print his images onto fabrics. With this knowledge, Weston began his unexpected journey into the world of fashion through digital textile printing, turning his hobby into a range of luxurious scarves.

Weston took his digitally printed scarves to the biannual Best of British Open Call event at the world-famous London store Liberty. The Open Call invites the public to show their products to the top buyers in the world, giving them the chance of a lifetime to sell in the London store. Weston attended the Open Call on a cold February morning in 2010. His passion and enthusiasm for his product was quickly spotted by top New York buyer Ed Burstell, who had recently joined Liberty, and his journey from passionate amateur to top-selling designer began. Maverick Television, who also attended the Open Call, documented the fascinating journey of Weston’s “Mineral Scarves” in an episode of the BBC2 reality series Britain’s Next Big Thing.

Weston’s designs are digitally printed onto the best silks by the finest digital silk printers in Como, Italy, maintaining the beauty of the original minerals; as a final touch, the edges of the silk are then “machine hand-rolled.” After securing an order from Liberty, Weston launched his first designer collection in June 2010. His vibrant “Mineral Scarves” are now a best seller in the scarf department of the prestigious London department store Liberty, displayed alongside designs by Alexander McQueen, Christopher Kane, and Jonathan Saunders.

Weston’s scarves demonstrate the rich possibilities that digital print offers and show how an amateur’s passion and love of natural forms can be translated into a beautiful product.

Richard Weston discovered digital textile design through his passion for collecting precious minerals and fossils.

Weston begins his design process by making a high-quality scan of a mineral sample. He then spends hours “cleaning” the image in Photoshop to enhance each stone’s remarkable qualities.

Using the very finest digital printing maintains the beautiful colors and details of the original minerals.

Weston translated the beauty of these natural forms into his “Mineral Scarves” collection, featured in the famous London store Liberty alongside scarves by other well-known designers.

RESIST DYEING AND DIGITAL PRINT

Resist dyeing techniques—such as tie-dye, batik, and shibori— are among the oldest textile-dyeing techniques. They are used all around the world and are still a source of fascination to many artists and designers today.

Shibori is the collective Japanese term for tie-dye, stitch-dye, fold-dye, and pole-wrap-dye techniques, which have been used for centuries as a textile craft all over the world. Chinese in origin, it spread to Africa, the Middle East, and India, and is still used today. Shibori ranges from simple resist techniques to advanced methods in which complex layers of color are built up. With shibori, it is possible to create not only two-dimensional patterns, but also three-dimensional designs, where the folding and wrapping used to achieve the resist areas is left in the cloth.

An element of surprise is always present in the making of shibori cloth, which contributes to its special magic and popularity, and can be used to complement the mechanical processes of digital printing.

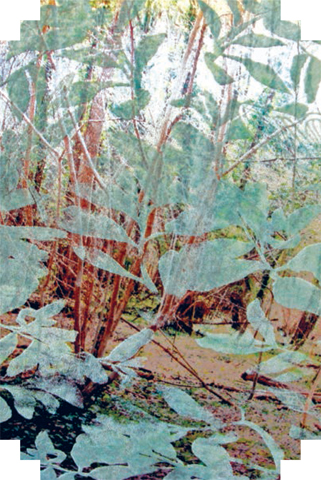

For her “Digital Shibori,” Melanie Bowles translated traditional shibori effects into mathematical geometrics using Illustrator.

Joanna Fowles created this shibori piece in the traditional way—by hand—before manipulating it in Photoshop and then printing it digitally onto silk.

EMBROIDERY, EMBELLISHMENT, AND DIGITAL PRINT

In recent years there has been a revival of the traditional crafts of knitting, crochet, and embroidery. In a world dominated by technology, many people enjoy returning to traditional techniques and creating garments and accessories by hand. At the same time, there has been a resurgence in the popularity of vintage garments and embellishments, which has also encouraged designers to look back at traditional techniques of hand- or machine stitching to add interest, value, and individual style to their own designs.

Today, designers are combining the traditional techniques of embroidery and embellishment with digital print to add a “handcrafted” element to their textile designs. If carefully applied, the two skills can complement one another.

Emma Rampton’s textile collection “Second Chance” consists of multifunctional garments that are designed to have a second life. The wearer is encouraged to customize and interact with the garment as time goes on. Working with contemporary and traditional imagery from domestic life, she combines new technology with traditional stitch techniques, worked back into the fabric.

Dominique Devaux sewed vintage embroidered sections onto digital prints to create her “Exotic Paradise” collection. The printed fabric echoes the real embroidered motifs, resulting in a look that successfully combines modern with antique.

Katie Irving Jones draws stitchwork patterns inspired by historic embroideries. She then scans and further manipulates them using imaging software. She prints her designs digitally onto a cotton/linen mix to give the effect of canvas work. Finally, she hand-stitches back into the motifs to give a personal, handcrafted touch to the fabric.

Andrea Patterson demonstrates her use of digital print and design techniques in combination with hand detailing to the fabric and garment, using appliqué, stitching, and trimmings such as lace, buttons, and ribbons.

Photini Anastasi’s digital collection retains her beautiful and sensitive drawings and watercolor paintings of landscape scenes from her childhood. She prints digitally onto viscose satin and then hand embroiders back into the images, imitating the lines and marks of her drawings.

HELEN AMY MURRAY

British-born textile designer Helen Amy Murray is an emerging talent, creating beautiful, luxury one-of-a-kind textiles for interiors and wall coverings. Murray was educated at Chelsea College of Art and Design, London. In 2003 she won the prestigious Oxo Peugeot Design Award, as well as a prize for innovation from the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA). She then set up her own label, HelenAmyMurray, and has now exhibited her work internationally.

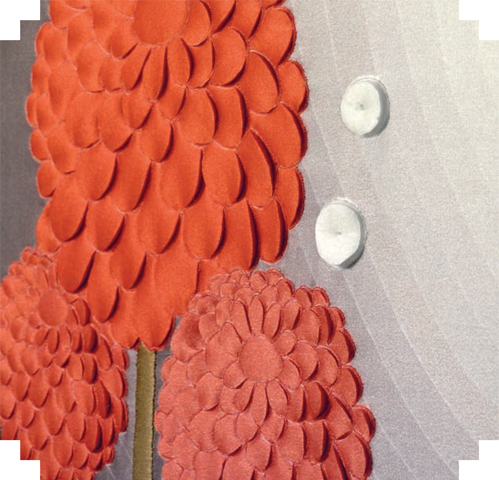

At Chelsea, Murray developed a passion for creating three-dimensional surface effects on various fabrics such as silk, leather, and suede. She has since developed a technique that has been recognized internationally for its unique handcrafted construction. She explains, “I’m excited about fabric manipulation and using innovative techniques, beautiful luxury materials, and design to create couture for the high end of the market.”

Murray’s inspiration comes from natural forms, from which she creates complex pattern structures using her unique technique. Her work achieves a strong graphic look, her innovative process creating sophisticated three-dimensional fabrics.

The designer’s work originates from her love of working directly with the surface of fabrics, so when she decided to take the bold move of exploring digital design she discovered a completely new way of working. “At first I felt nervous working in a virtual medium. As I have a very physical and tactile relationship with fabric, I felt I was entering the unknown. But once I had completed the process of designing and digitally printing and had applied my technique, I could see the possibilities that it would give my work. I love the subtlety of color that digital print can achieve and the layers of pattern and form. It allows me to work with more complex and fantastical imagery, which gives my work a new narrative.”

Murray’s highly individual and sensual approach to textiles allows her work to develop without compromising her aesthetic values. She has merged digital print so well with her own cutting techniques that she has managed to create a truly “digitally crafted” textile.

For her “Art Deco Chair, Two-headed Bird with Sunrays” (2005), Murray integrated a digitally printed piece into her sculpted leather fabric, which was then upholstered onto a classic art deco chair. She scanned her hand-drawn image of an exotic crane, which she then adapted using imaging software. This was then digitally printed onto silk crêpe satin and carefully appliquéd onto the leather before she applied her cutting process. The digital print on silk satin allowed her to introduce an intricate gradient of color, adding both depth and movement.

“Birds and Flowers” (2005) is an ambitious art piece. Initially working and adapting her design using imaging software, Murray dropped in color blends and gradients, then printed the artwork digitally. Drawing back into the design with her cutting tool to create a sculpted 3-D effect, she gave further detail, definition, shadow, movement, and depth to the piece. Finally, she framed it in wood covered with foiled leather.

PRETREATMENT OF DIGITAL FABRIC

All fabrics used for digital printing must be pretreated before use. The Textiles Environment Design (TED) project at the Chelsea College of Art and Design, London, looks at the role the designer can play in creating textiles that have a reduced impact on the environment, and provides a toolbox of designer-centered solutions. Part of the resource offered by TED investigates the coating of organic fabrics so that they are suitable for digital printing, such as organic cottons, linens, and hemp. These fabrics are specially coated by a digital print bureau. Melanie Bowles has created a collection, “Material Attachment,” that is digitally printed onto a hemp/silk mix, proving that rich and vibrant colors can be achieved. The use of organic hemp/silk introduces a new fabric for digital print that has a beautiful surface and subtle sheen.

In her “Material Attachment” collection, Melanie Bowles drew inspiration from historical textiles. The collection was shown at Ever & Again, an exhibition at Chelsea College of Art and Design in 2007 which looked at recyling textiles. Melanie relined a favorite coat with digitally printed organic hemp/silk mix fabric to give it a new lease of life.

DIGITAL PRINT ONTO VINTAGE FABRICS

Nicky Gearing and Debbie Stack from the London College of Fashion experimented with the pretreatment process as part of an international research project with the Creative Industries Faculty at the Queensland University of Technology, Australia, in 2004. This was a design exercise featuring reworked vintage clothing dating from the 19th and 20th centuries donated by the National Trust of Queensland. Gearing and Stack screen printed the pretreatment paste— consisting of sodium carbonate, Manutex, and urea—onto an original Victorian damask. The vintage fabric took the inks successfully and withstood the after-treatment of steaming and washing well. They produced an interesting range of samples on various fabrics, integrating discharge and screen-printing techniques with digital print. Digital embroidery was applied to the fabric before the pretreatment, and also as a final embellishment after printing to create a rich surface quality. The project resulted in a collection of fabrics that show the potential of pretreatment on fabrics not normally used for digital print.

Digital print on vintage damask, appliquéd onto a traditional ticking cotton and combined with screen printing.

Digital floral print on dyed ticking fabric, combined with discharge printing.

The rise of mass production and consumerism has led to a craft-focused backlash, and more people are now interested in DIY design-and-make. Amateurs are finding ingenious ways to personalize and customize their own products—and not just in the domestic arts, but in graphic design, journalism, and publishing, too.

You no longer have to be a trained graphic designer to create personal graphics such as business cards, logos, mouse mats, greetings cards, and simple websites. Imaging software is now available as a design tool for all to use and the desktop printer has developed into a key method of print production for all kinds of graphic materials. Craft enthusiasts are now embracing the hands-on digital technology that is available from the home, and this extends to textiles, primarily through inkjet transfers and sublimation printing.

Andrea Patterson prints her designs onto opaque transfer paper and then applies this to contrasting cotton muslin. The “plastic” quality of the opaque transfer adds texture and contrasts with the coarseness of the natural cloth.

In her collection “The Old Farm House,” Catherine Frere-Smith incorporates a fabric kit so her design can be made into a garment or a fabric house.

INKJET TRANSFERS

The simplest and most direct method of inkjet printing onto fabric is by running inkjet-transfer paper through a printer and then applying the pattern onto fabric using heat, either with an iron or, ideally, in a heat press. The paper is a special polymer-treated paper which is manufactured for use as a T-shirt transfer, and is available from stationery and computer suppliers. It is designed for use with water-based inks. In the past the paper left a “plastic” feel to the fabric, but now a softer result can be achieved. It works best on white or pale fabrics, but there is also an opaque paper available that can be used on darker fabrics, though this will leave a plastic feel.

This simple method of printing, which can be done using most desktop printers, has created a surge in DIY design and print for the amateur craft and hobby sector. Adults and children alike are enjoying this hands-on and immediate approach to transferring images onto mouse mats, jigsaws, coasters, and clothes.

Of the “craft” hobbyists, it is perhaps the quilter who can find the most creative potential in this method of printing. It is possible to apply a nontoxic chemical formula to a fabric to make the image permanent. This is applied by first soaking the fabric in the solution and, once dry, ironing it onto freezer paper. The fabric can then be fed through the printer. Quilters require small, sample-sized amounts of fabric to work with, and, using the inkjet transfer technique, they can create many individual designs to incorporate into their work. Added to this is the tradition of a quilt as a valued artifact that is passed down from one generation to the next. Using this new technology, they can include photographic imagery in their work, adding a highly personalized and powerful sentimental quality to the quilt, which is changing the aesthetic of the craft.

The bell-like dress used by textile artist Shelly Goldsmith in her “Fragmented Bell” (opposite page, bottom) was originally hand-stitched by the employees of the Children’s Home of Cincinnati. The panoramic image of the piece references natural disasters—in this case a tornado. Goldsmith digitally manipulated the photograph in order to fragment the plane of the image to reference the actual fragmentation of the domestic landscape.

Goldsmith used reclaimed christening dresses to create “Baptism” (opposite page, top left). The dress references the use of water in the christening ceremony, while also commenting on how these garments are handed down and reused over many years. As in “Fragmented Bell,” the dress shows the image of a natural disaster and raises the notion that cloth retains a type of memory that cannot be erased. The gown has been transfer-printed with digitally adjusted photography, carefully pieced together to create a panorama effect around the garment.

Zoe Barker uses the inkjet transfer method to build up complex fabrics for her children’s collection, “Second Life.” She encourages children to interact with the clothes and appreciate their worth with her “customizing kit,” containing transfers, badges, buttons, and ribbons, which can be added to personalize the garments.

Alice Potter enjoys the immediacy of translating her designs from sketchbook to fabric via her desktop printer. She produces small fabric samples that she then pieces together to create patchworks such as this one, entitled “When I Sleep I Dream of Play.”

The technique of transfer printing is used by aforest-design to present a limited edition of odori tabi socks designed by Sara Lamusias. The tabi is a traditional sock from Japan that is used in the home or is worn with sandals. These photo-collage designs were transfer-printed onto cotton socks.

Textile artist Shelly Goldsmith creates her poignant textile pieces using a desktop printer to print digitally onto transfer paper. She meticulously jigsaws her images together by hand and irons them onto fragile, reclaimed garments. Collaging her images allows her to maintain a handcrafted quality to her work.

SUBLIMATION PRINTING

Dye-sublimation printing is a versatile method of printing using disperse dyes—available in cartridge form for large-format printers and for desktop printers—onto polyester fabrics. It is widely used in the promotional marketing industry for printing products such as jewelry, place mats, marble, ceramic tiles or mugs, skateboards, aprons, and other items of apparel. The majority of products printed using this process are somewhat crude in design, but there is huge potential to develop more sophisticated work. Many designers are now exploring this method of print, not least because the transfers yield stunning and beautiful photorealistic results, with vivid colors.

There is a wide range of polyesters available from fabric stores. These range from novelty fabrics to satin to metallic lamé and from stretch-knit jerseys to Lycra®. The affordability of these fabrics gives scope for the textile designer to experiment. Some fantastic results can be achieved with the vivid, clear colors of polyester.

In the textile industry, sublimation printing has mainly been used for printing on sportswear and swimwear. However, setting up a desktop print system is now proving to be an affordable option, and many textile designers, studios, and educational establishments are now exploring the possibilities of sublimation printing onto the large variety of polyester fabrics that are available. The choice of polyesters can range from Aertex, polymesh, lamé, satin, Lycra®, organza, and fleece to an array of novelty fabrics, but the higher the percentage of polyester they contain—preferably more than 60 percent—the better the results. It is always best to test fabrics as many do not state the proportion of polyester that they contain.

In the past, polyester has been uncomfortable to wear and has lacked the qualities of natural fabrics such as cotton. Recently, however, a number of manufacturers have come up with new processes that have resulted in soft, breathable, and comfortable fabrics. Polyester is also inexpensive, allowing designers the freedom to experiment with this hands-on method to create innovative print effects. Samples can be produced immediately, which is perfect for the ever-increasing pace of the fashion industry, where ideas need to be realized instantly.

Taina Lehtinen’s handbag collection was created using sublimation printing onto faux suedette, showcasing the photographic qualities that can be achieved with this process.

Chetna Prajapati pushed the potential of sublimation printing in her edgy streetware collection “One Tribe, One Style.” She printed on a range of polyesters, combining them to create her garments. The quality of the colors and the definition of the digital print is so strong that some colors look fluorescent; the metallic polyesters add sharpness to the graphic geometric designs.

Prajapati also used sublimation printing to create this beautiful pleated fabric. She printed a metallic polyester using the dye-sublimation technique, applied a pleating template, and then heat-pressed the fabric into shape.

Victoria Collins tests a wide range of polyesters, such as neoprene and Lycra®, before bonding them together to create new surfaces. Her sketchbook demonstrates the importance of testing different fabrics. She finds that most need to be heat-pressed for 60 seconds at 350°F, but care must be taken with nylon as it can melt quickly under a heat press.

Temitope Tijani used the sublimation technique to transfer her designs to plastics to create a stunning geometric accessories collection.

REBECCA EARLEY

Rebecca Earley is a lecturer in Textiles Environment Design at Chelsea College of Art and Design, London. She is an award-winning fashion textile designer who produces textiles for her own label, B.Earley, which she set up in 1995 with backing from the Crafts Council and the Prince’s Trust. A practice-based design researcher, her work encompasses a wide range of design-related activities including producing digitally printed textiles for her own label, undertaking public art projects and commissions, and acting as an educator, facilitator, and curator.

Earley graduated from Central Saint Martins in 1994 and her graduate collection was widely recognized as groundbreaking. The heat-photogram print technique that she pioneered has since become an industry-standard process.

Earley’s collections demonstrate how the designer can work fluently with digital technology and handcrafted techniques. She retains the original handcrafted look of the heat-photogram process, in which she paints disperse dyes directly onto transfer paper, places a real object directly onto the paper, and applies heat to transfer the image onto polyester. Now working digitally, she scans in the original photogram artwork and then rearranges it using imaging software. This gives her the scope to change the scale and composition of her artwork, and more freedom to experiment. Her designs are printed out on a desktop printer using sublimation printing.

In the collection featured here, shirts have been created and delicately embellished with stitched and pleated details inspired by research into traditional English gardening attire and images of old garden artifacts. Earley uses the digital process as another tool to integrate into her creative process.

In 1998, Earley’s interest in the environment prompted her to analyze her own studio design and production practices. She subsequently developed an exhaust printing technique that produced hand-printed textiles with no water pollution and minimal chemical usage. She has continued to investigate new techniques and theoretical approaches to textile design, working on a variety of projects, including Natural Indigo at the Eden Project; Well Fashioned, an exhibition of eco-fashion at the Crafts Council Gallery; Ever & Again: Rethinking Recycled Textiles, a threeyear project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council; and Top 100, a long-term polyester-shirt recycling project.

In 2002 Earley joined the Textiles Environment Design (TED) project—a research project where staff and students work collaboratively and on individual projects. This unique research cluster seeks to explore the role that the designer can play in producing more environmentally friendly textiles. TED places the designer, rather than the manufacturer or consumer, center stage, since “80–90 percent of total lifecycle costs of any product (environmental and economic) are determined by the product design before production ever begins” (“More for Less,” Design Council Report, 1998).

TED has developed a series of environmentally friendly principles and strategies, including minimizing waste; using less harmful substances, energy, and water; utilizing new low-impact technologies; designing systems and services to support textile products; and creating long- or short-life textiles. Social and cultural awareness and concern for the environment have grown exponentially, and Earley and TED have played a key role both nationally and internationally in creating and promoting eco textile design.

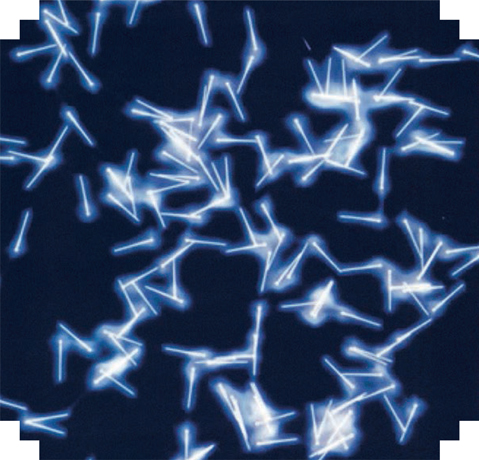

Rebecca Earley’s “Top 100” (2002–8), featuring a heat-photogram print.

Earley’s “Digital Photogram Collage” was created using heat-photogram prints on fabric, which was then digitally scanned and manipulated and digitally printed.

“Pin Print” (1995), heat photogram.

“The Conscious Gardener” (2007) combines digital and sublimation printing with hand-painted transfer techniques.