Animation is a compeling and extraordinarily adaptable form of audio-visual expression that is highly effective in fusing moving images and sounds together to tell stories and explain ideas. The medium allows exponents to explore theories and inform audiences, and its flexibility as an artificially constructed form means that it is well suited to a vast range of communication applications. From obvious examples such as movies, television series, and advertising commercials, through developing uses such as websites, mobile applications, and gaming, to more diverse applications in the fields of medicine, engineering, and architecture, animation proves that it is a medium that has the ability to entertain, inform, educate, and inspire. Animation permits and encourages the creation of cinematic visual trickery by making unreal events seem real and transporting an audience to new places of discovery. Major Hollywood studios are increasingly turning to animation and special effects (SFX) techniques to realize their creative ideas, and other organizations and governments are also waking up to the possibility of using animation to explain, reinforce, or promote their message.

In recent decades, animators have found increasingly inventive ways of using animation. Today it pervades much of the landscape of popular culture, being a medium of choice to push boundaries, cross traditional disciplinary divides, and support and enhance other creative work. While animation’s history is relatively short compared to other arts disciplines, this needs to be juxtaposed against the prolific and accelerated advances in technology, such as the growth of the Internet, the developing reliance on mobile technology, and the need for greater visually oriented support for social media. Such technical leaps have created changes in global social and economic conditions and have encouraged increased interest in the subject of animation—an interest that is likely to grow and spread over the coming years.

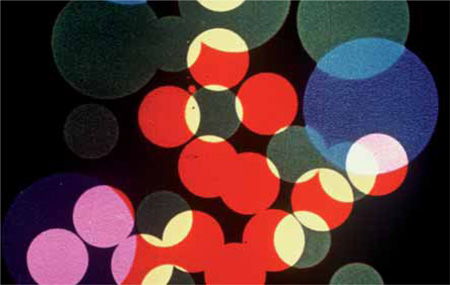

The spirit of animation as an evolving form of audio-visual expression is encapsulated by Oskar Fischinger’s Kreise, released in 1933.

The significance of animation

In his book The Fundamentals of Animation (2006), Paul Wells states that: “Animation is the most dynamic form of expression available to creative people.” When one starts to examine the subject in depth, it becomes clear that animation has a profound effect on the daily lives of many of us. Most people experience animation through children’s television programming and animated feature films. Some of the greatest sequences in world cinema are animated feature films that are etched into our collective memories. Who can forget the magical “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” sequence in the 1940 film Fantasia? Or, in the more recent realms of animation history, the enchanting story of Carl and Ellie’s love affair, life, and passing, in the Disney•Pixar animated feature film Up (2009). These collective memories and experiences are largely attributed to the dominance of the greatest pioneer in animation history, Walt Disney (1901–66). The impact that the Walt Disney Studios has had on cinema audiences—indeed on popular culture generally—is vast and far-reaching, albeit supported by important outputs from Warner Bros. and UPA (United Productions of America). However, this American “super studio” dominance has also meant that other versions of animation have sometimes been overlooked or not given the credit they deserve by mass audiences.

Walter Elias “Walt” Disney (1901–66) is indelibly linked to the growth and development of animation. The company he cofounded with his brother Roy, the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio, has today evolved into The Walt Disney Company and is a media and entertainment powerhouse. © Disney

For many, the true significance of animation can be measured by such elements as its inclusion in the annual Academy Awards, the growth of international film festivals, the distribution of feature films, documentaries and short films on cable or satellite channels, and the Internet revolution that has opened up new audiences for the form globally. Furthermore, the study of animation as a subject in its own right—including its history, technical advances, and wider cultural context—is recognized through a multitude of internationally published specialist magazines, academic journals, seminars, and conferences, trade magazines, online forums, blogs, and microblogs.

Uses of animation

Animation has the potential to reach developed, fledgling, or emerging audiences in a way that live-action film is unable to because of subjective, cultural, or technical shortcomings. The form can seemingly make the “impossible” possible and has the potential to communicate with young and old alike, regardless of ethnicity, gender, religion, or nationality. If used intelligently, animation can draw viewers together, crossing boundaries and uniting audiences under thematic ideas and concerns, making it a very attractive medium for artists, designers, producers, directors, musicians, and actors to use to recount stories, ideas, and opinions to a diverse range of cultures.

In many walks of everyday life animation is used to explain concepts, deliver important information, promote goods and services, and keep us on the move. Over the last few decades, animation has played its part by both driving and supporting the technical and conceptual demands of a wider world. We now see the medium used to track satellites orbiting the Earth, explain the power of the planet’s weather systems on oceans, mountains, and deserts, predict the force of earthquakes, or suggest possible worlds beyond our solar system. Animation is employed to deliver specific engineering data, integrate complex pharmaceutical and clinical procedures, and develop research models to enable a broad range of activities to occur in many different and varied fields. From being the central core of an animated feature film or supplying particular special effects in a live-action feature, right the way through to animated applications on a cell phone or animated navigational buttons on a website, animation has a role to play in imparting content to the audience.

Animated physics-based simulations are used to spectacular effect at the American Museum of Natural History, where the film Journey to the Stars explores the life cycle of stars through an immersive audience experience.

A model for future communication

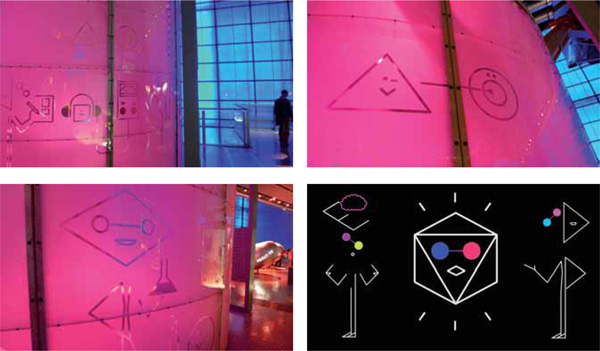

The success of animation as a communication form in the future may lie in its residual power to be designed and read in myriad screen formats. The advent and growth of digital technology has revolutionized the way that audiences access and watch animation. Digitization has streamlined the production and delivery of animation and has broadened the scope for audiences to become familiar with the subject. Cinema and broadcast media have evolved with three-dimensional (3D) projection, specialist surround-sound features, and satellite and cable content, but with the development of mobile technology delivery is no longer confined to a fixed place, meaning that animated functionality and content features widely on games consoles, smartphones, and MP3 players. Furthermore, animation is also “screened” in increasingly unconventional yet interesting ways as part of live-action performances, art installations, and exhibitions, and in virtual- or augmented-reality worlds where it can either lead or support other material.

Animation is also able to contribute toward our understanding of the shape of our future. Unlike live action, animation can be used to creatively predict scenes through imaginary visualization, rather than simply record events or situations from life. Additionally, certain animated sequences have the advantage of being significantly cheaper to produce than live-action equivalents, and can provide greater information for the audience in a fraction of the time it would take to explain these occurrences in the real time of live action, as information can be overlaid or run concurrently, enriching the viewing experience.

Animation can also borrow, appropriate, and assimilate other research material from compliant resources. A good example is beamed satellite information in the articulation of animated maps on satellite navigation systems in vehicles. The animated graphical user interface (GUI) is designed to present this instant information to the driver of the vehicle clearly and coherently, not only finding the way to a destination, but also updating data to warn of hazards that lie ahead and communicating alternative actions.

The world of augmented reality through mobile devices opens up huge possibilities for animation to play a vital role in imparting and explaining information from a remote source in a real-world, real-time setting. Various organizations, institutions, and groups are focused on exploring the possibilities of this emerging technology for industrial, economic, and personal use, whether through illustrating animated walk-through visualizations of property for sale, providing interactive museum or gallery guides, or making hiking more exciting by providing an interactive commentary and alternative view of the outdoor landscape.

French pioneer of early cinema, Georges Méliès, experimented with techniques such as double exposures and dissolves in his magical fantasy, Le Voyage dans la Lune (Voyage to the Moon, 1902).

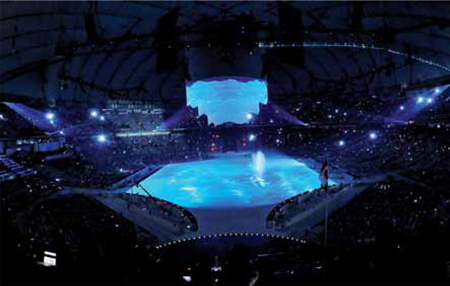

The special effects created by Spinifex for the opening ceremony of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Canada, merged 3D animated whales projected onto a virtual Pacific Ocean inside the stadium, with each breach triggering a physical waterspout.

The defining principles of animation

The word “animation” derives from the Latin verb animare, meaning “to give life to,” suggesting that the illusion of movement has been given to inanimate forms. Animation essentially involves the artificial creation of images in a sequence that appears to move through the “persistence of vision”: our eye reads the images in quick succession and our brain tricks us into believing that the images are moving. In reality, the movement is created by the spaces in between the frames. The Scottish-born animation pioneer Norman McLaren famously said: “Animation is not the art of drawings that move, but rather the art of movements that are drawn.”

In technical terms, the basic principle of creating animation is that images are captured singly through a photographic lens or a scanner in a predetermined order. These shots become records of the single images and are known as “frames.” When the recorded frames are played back in chronological order, they create a collection known as a “sequence” that appears to make the images move on screen. Different frame rates are required for different viewing experiences. For example, a common frame rate is 24 frames per second (fps) for television and film production (although some countries’ broadcast formats differ, and 25 fps is a recognized format), but where animation is created for online output, slower data-processing speeds caused by reduced or fluctuating bandwidth mean that a reduced number of frames is preferable, despite altering the fluency of movement.

Capturing individual frames on flat surfaces (paper, cels, or digital files) relies on “registering” or “keying in” individual frames into an exact position so that the shooting of each frame is consistent and controlled. Through the digital advances that have been made from the traditional approach to animation, pioneered throughout the first half of the last century, much of traditional cel drawing and painting is now done digitally. The process of stop-motion animation involves the gradual movement of an object or artifact under or in front of a fixed or incrementally moving camera, capturing each slight movement as a single frame, and then playing this back to see a progression of recorded moving imagery.

These background cel paintings from the animated feature film Akira (1988) demonstrate the layering technique employed to create complex scenes using registration marks to ensure continuity.

While good animation requires technical knowledge and understanding to produce smooth, logical, and coherent movement, great animation assumes this knowledge as a given and provokes and entices the creator to produce work that synthesizes technical prowess with more substantial emotive and conceptual ideas, celebrating and enriching the central idea, theme, or narrative of the production.

Twelve principles of animation

In 1981, legendary Walt Disney Studios animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston (two of Disney’s “Nine Old Men”) set out some defining principles of the form in their book The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation (1981). The title alludes to a central theme in animation education—that if creators using animation desire the ability to reimagine life, they must first understand the nuances of life itself. The book describes twelve central principles to link animation to the natural laws of physics while embodying the idea that the process of animating could contravene and contradict these laws within reason. This logic would be an unwritten trust between the animator and his or her audience.

Two of Walt Disney Studios’ “Nine Old Men,” Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, believed that creating lifelike animation could only be achieved by understanding the nuances and complexities of the natural laws of physics applied to the human body. © Disney

• Squash and stretch—this principle acknowledges that objects have an implied weight and flexibility, and recognizes that when an object moves, its weight shifts through the flexing of its form. The bouncing ball is often used to illustrate the principle, where the form at its lowest point (impact) is illustrated as a squashed ball, while its accelerated rise to its highest point is illustrated as a stretched ball, recognizing that the gravitational forces inside the ball are moving.

• Anticipation—in reality, any movement is prefigured by the desire, intention, or need to move, and the body prepares itself for the predicted action. In animation, creating the illusion that the body is mindful of this anticipation gives life and credibility to the object. An example might be a baseball pitcher drawing back his arm before throwing the ball to the striker.

• Staging—this involves composing elements of the frame to control the viewers’ experience. So placing characters in particular positions, lighting them in certain ways, and positioning the camera to record these deliberate intentions all accentuate the appearance of the subject in its surrounding environment, contributing to the audience’s understanding and enjoyment of the piece.

• Straight-ahead action and pose-to-pose drawing—straight-ahead action concerns the movements of individual figures in staged scenes, and is best demonstrated by first imaging a simple action and then drawing each frame of that action from the start to the finishing point. This creates movements that are highly detailed and fluent and are described as “full animation.” Pose-to-pose drawing is a more economical approach, using fewer frames and resulting in a more dramatic and immediate effect. Animators often use both straight-ahead action and pose-to-pose drawing, mixing the two subtly to reflect the focus, pace, and concentration of the story being animated.

• Follow-through and overlapping actions—the laws of physics dictate that after a body (human or object) has stopped moving, the momentum created by its movement is continued, or “followed through,” before coming to rest within the body. Acknowledging this principle and building it into the depiction of the figure or object results in a more believable movement. Similarly, observation of a body acknowledges that elements of the human form move at different speeds from each other and create “overlapping actions.” A good example might be the contrast between fleshier and bonier parts of the body. Building in these differences in movement gives believability and sensitivity to the form, allowing the viewer to suspend disbelief.

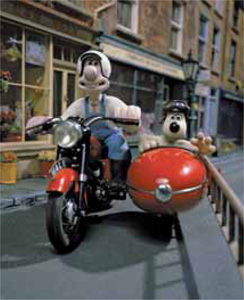

The defining principles of animation are neatly embodied in the work of the British Aardman Animations studio, ably demonstrated by the enduring pairing of Wallace and Gromit.

• Slow in and slow out—not all actions happen at a uniform speed, but there are instead periods of acceleration and deceleration that appear to reflect the subject’s natural reactions to a movement. To achieve this, a greater number of frames is created at the beginning and the end of a moving sequence, resulting in more naturalized and believable movement.

• Arcs—animators use implied arcs to emulate natural movements to aid believability. Reflecting the speed of an action, arcs emulating faster movements are stretched over longer distances with low peaks, while in slower movements the arc is shorter with a higher peak to reflect a shorter distance. For example, a baseball pitcher throwing a fast ball will be illustrated by the ball following an invisible stretched arc.

• Secondary action—this principle recognizes that movements seldom happen in isolation. The simple act of walking (primary action) might be complemented by the ability of the figure to chew gum, talk to his girlfriend, and wave his hand.

• Timing—the importance of timing is translated through the number of frames designated for an action to occur, controlling not only the speed of the action but crucially also introducing, establishing, and reaffirming wider conditions, such as the characters’ emotional state and their connection to the plot or other characters.

• Exaggeration—the principle of exaggeration, whether applied to the physical design and actions of characters, or to the wider narrative function of the animation itself, presents opportunities to stretch and distort reality, achieving seemingly impossible feats by amplifying conditions and breaking rules and conventions.

• Solid drawing—this involves the confident handling of drawing as a three-dimensional discipline articulated through understanding anatomy and form. Solid drawing helps to maintain believability.

• Appeal—understanding the intricacies of drawing gives “appeal” to characters and makes them interesting focal points for the audience to make necessary plot, design, or associated connections with. In this sense, appeal is not necessarily “attractive,” but rather an embodiment of character traits that touches an emotional inner core in the audience.

Taking time to understand the principles of animation is important, as they form a critical and universally recognized framework. It is equally important to understand how an animated production is created. All animation projects have a workflow, known as a “pipeline,” that recognizes three distinct phases: preproduction, production, and postproduction. To understand this pipeline it is useful to outline a simplified animated workflow that clearly identifies the logical steps needed to construct an animated film (see below). However, when considering this outline it is important to keep in mind that some creators do not come from traditionally recognized backgrounds of art and design, but from diverse though associated areas of interest such as music, film, photography, engineering, and architecture. These creators may deviate from this traditional workflow depending on where the inspiration for the production comes from, the resulting constituent parts that it uses, the production processes employed, and the method of screening the final film, episode, ad, or application. It is even possible that some aspects may be omitted altogether for a variety of perfectly sound and justifiable reasons.

Preproduction

In the preproduction phase, scripts, visual and sound concepts, and ideas are explored and tested through research in order to prepare material before filming and recording.

Briefing: A project is originated personally, commercially, or for non-profit organizations, including details of client requirements, budget, timescale, and technical constraints. Depending on the nature of the project, production companies may be asked to pitch for jobs, or an agency might approach a particular director having seen examples of previous work that the client has indicated they like. In independent animation, the animator often writes a synopsis to try to attract funds from funding bodies, organizations, or external sponsors. The director is tasked with envisioning the project through to completion.

Script: The script is written in response to the brief given, and may be based on an observation, an interpretation of an event, or an adaptation of a story. The script is completed, analyzed, and edited, until the contents are agreed.

Concepts and ideas: The script is given to a director, who directs the crew to interpret the material visually and aurally. Concepts are explored and developed, and the resulting ideas are given rough visual and aural forms so that first impressions of the production can be formed and considered.

Research: Ideas are explored through more focused and sustained research, collecting information through observations and recordings and assembling this material into a methodical order that can be used in the studio environment to add more detail and expression to the initial ideas.

These previsualized images give an indication of the overall feel of the intended output.

Treatment: The project is pitched to the client or funding body through a written synopsis known as a “treatment,” where the story or idea will be summarized through a presentation comprising one or more of the following elements: a written statement, visualized images (or a storyboard), a temporary soundtrack, sample voice-overs, and atmospheric special-effect ideas. The production method of creating the work is established and agreed according to the budget set or established for the production, and the release format is agreed.

Storyboard: A storyboard is developed to illustrate the emerging narrative, setting the scene, introducing characters, establishing where dialogue fits with action, suggesting camera shots and angles and determining sound effects. This is tested as an “animatic,” merging vision and sound to start to make sense of pacing and timing of the material for the audience. As the production develops, so does the quality of information held on the storyboard.

Development: Sets, scenes, and characters are visually developed in tandem with the collected research material as the crew work out how to animate the information contained in the storyboard. This involves detailed analysis of how the production is constructed (how to move items on set, how characters walk, talk, and interact, how lighting will be set and cameras will capture each frame) so that any production issues are resolved prior to filming. The production schedule is established and published for the crew.

Sound: The choice of “sound stems,” dialogue, narration, music, and special effects is finalized and designed in close conjunction with the visual development taking place. Music is commissioned if a score is required, voice talent is auditioned for narrative and dialogue roles if needed, and the crew working on special effects are tasked with originating or collecting relevant material that can be first recorded on location or in the studio, before being edited in the studio and mixed together to form a soundtrack.

Animation can be used to enhance an audience’s understanding of a story or set of ideas, allowing the possibility of an interactive experience.

Production

The production phase sees the project take shape, with artwork being created, film shot, and sound recorded.

Production for 2D animation

Creating key frames: The major frames of action are drawn as key poses for the central characters.

Motion tests: Character movement is tested through pencil tests to make sure movements are fluid, coherent, and in keeping with the character’s personality and appeal.

Backgrounds: Scenes are illustrated to provide a backdrop against which character action takes place and to contribute to the overall mood and atmosphere of the production.

In-between frames: Cels are drawn in between the key frames to render the whole action of the character. The cels are shot or scanned and cleaned up and saved as individual frames in the software program.

Sensitive lighting design can radically alter the mood of a production.

Inking, painting, and compositing: The frames are artworked to render them in a final state, building up details on individual layers if necessary to achieve an overall look through compositing.

Picture editing: The frames are played back to check for accuracy, speed, and coherence within the story.

Rendering: The layers in the frame are flattened through a process known as “rendering” to create final frames.

Workprint: Whether working in two or three dimensions, special effects are considered along with music, narration, and dialogue to create an intermediate version of the production, known as a “workprint.” This helpfully establishes the shape of the production, illustrating its appeal and values, as well as highlighting the inconsistencies, mistakes, and faults.

Production for 3D animation

Modeling: A character or object is sculpted and formed through development drawings and research to remain faithful to the creator’s vision of it.

Rigging and animating: This process establishes how the modeled form will move, either manually through the animator flexing the form, or digitally through permissions granted in the software application to “handle” the form on a predetermined axis, through walk cycles, lip-synching, and so on.

Effects and lighting: Visual effects in support of the main movements of the form are executed and recorded, often worked in tandem with lighting design to evoke atmosphere and create highlights on aspects of the form for dramatic purpose.

Compositing: Recorded three-dimensional elements are brought together, manipulated, and outputted, often changing the feel and impetus of the recorded footage to maximize dramatic impact and accentuate the story or idea in an interesting way for the viewer.

Rendering: As with 2D animation, the layers in the frame are flattened through the rendering process to create final frames.

Workprint: And like in 2D animation, a workprint is created by looking at the special effects, music, narration, and dialogue all together.

The postproduction phase takes all the collected filmed and recorded material and synthesizes it into a product, adding special effects and titles, so that it is ready for release and distribution.

Special effects: The concluding stage of the project allows special effects to be placed, accentuated, and mixed to enhance the viewing and audio experience.

Panning: The sound can be further designed into a supportive landscape for the visuals, placing sounds in different parts of the auditorium by controlling how the speakers will output the recorded sound stems.

Color correction and mastering: The working print is fine-tuned, removing any minor inconsistencies and creating a seamless and pure visual and audio experience.

Titles and credits: The work is prefixed and suffixed by the titles and credits respectively, acknowledging the role played in creating the animation for screening by the crew, the funders, the producers, and the broadcaster’s supporters. A release print is made through the studio or a specialist photographic lab, depending on the agreed release format.

Release and distribution: The completed work is distributed through distribution agents who liaise with broadcast networks, organizations, or festivals to screen the work for consumption.

Academy Award-winning British animator Suzie Templeton is renowned for the high-quality construction of her animation sets.

About this book

This book aims to explore animation in an easily digestible, inspiring, and exciting way. The subject is introduced from the perspective of following a traditional workflow, or pipeline, as outlined above. The chapters that follow reflect these stages of preproduction, production, and postproduction and are intrinsically linked to originating, developing, and creating an animated film.

Chapter One: Preproduction—Planning and Scriptwriting explores the scheduling of an animated production and gives an overview of the roles and responsibilities of crew members working on the project. The chapter investigates practical approaches to writing for animation as a form different from cinema. It introduces key concepts of animation vocabulary and language, and emphasizes the interpretive possibilities of the form, both linguistically and stylistically, for the creator.

Chapter Two: Preproduction—Concepts, Ideas, and Research examines where ideas originate and how they are developed using a framework to test, evaluate, and strengthen them for the creator and audience alike. The importance of relevant research and associated research processes is explained, including the importance of accuracy in collation and archiving of materials, and how these can be utilized in the development of ideas.

The Ottawa International Animation Festival held every year in Canada celebrates the best new releases from Canada and the rest of the world, with its “Meet the Filmmakers” slot being especially popular.

Chapter Three: Preproduction—Development looks at the art of storyboarding, layout, and drawing as essential tools and processes to enable the animator to develop his or her project.

Chapter Four: Preproduction—Sound looks at the definition and use of “sound stems” as an important part of the preproduction process in defining and shaping the animation. Narration, dialogue, music, and special effects are considered, allowing the reader to understand how sounds are recorded, edited together, and processed ready for production.

Chapter Five: Production examines the variety of production methods used to create visual and aural animated content using common techniques, such as cel animation, stop motion, computer-generated imagery (CGI), and more unorthodox and unusual methods.

Chapter Six: Postproduction explores the integration of the visual, aural, and special-effects aspects of the animation process into a cohesive package ready for distribution and viewing. The chapter explains the analyzing, editing, rendering, and packaging process as the animated production is prepared for release and distribution.

Chapter Seven: Animated Futures looks at careers in animation and contains useful reference information about how to prepare for and find employment through education and training, and by gaining experience through placements and internships.

Through the use of specifically researched illustrations and captions this book enhances the reader’s understanding and knowledge of the medium and provides a rich and enjoyable overview of the animation process. Information in the text and boxed features gives valuable guidance and support to student animators creating animation and wanting to expand their education into a career in the field. Key words and technical terms are defined in more detail in the glossary section at the end of the book and a comprehensive bibliography highlights further reading opportunities.

This timeline documents the history of animation through developments in technique and technology over the last two centuries.

1779

Paul Philidor creates the first acknowledged phantasmagoria show

1798

Stage magician Étienne Gaspard Robert pioneers the idea of the phantasmagoria “production”

1832

Joseph Plateau invents the phenakistoscope

1834

The Daedalum (later known as the “zoetrope”) is designed and produced by British mathematician William G. Horner

1854

Austrian Franz von Uchatius invents the kinetoscope, which is then further developed by Thomas Edison

Praxinoscope (1877)

1877

In France, Charles-Émile Reynaud patents the praxinoscope, which introduces mirrors to the principle of the original zoetrope

1896

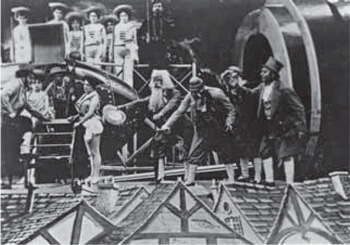

Frame-to-frame trick effects are pioneered by French filmmaker Georges Méliès

1901

Walter Elias (“Walt”) Disney is born in Chicago, Illinois

1902

The first transatlantic radio message is received in Britain, originating in the United States

1906

J. Stuart Blackton creates the first cartoon, Humorous Phases of Funny Faces, using animated chalk drawings that are double-exposed on negative film

1907

The Teddy Bears is created by American Edwin Stanton Porter, using stop-motion figures

1908

Émile Cohl, the Parisian caricaturist, releases Fantasmagorie, widely considered to be the world’s first fully animated film

Fantasmagorie (1908)

1910

Russian animator Vladislav Starevich creates Piekna Lukanida (The Beautiful Lukanida), the first puppet animation to use stop motion

1911

International Business Machines (IBM) is founded. Winsor McCay, the prolific newspaper cartoonist, animates figures in his film Little Nemo in Slumberland from his comic strip of the same name

Gertie the Dinosaur (1914)

1914

Winsor McCay creates Gertie the Dinosaur, the first animated film to feature a character with a recognizable personality and to be made using the key-frame technique. Raoul Barré and Bill Nolan set up the Barré-Nolan Studio, the first commercial cartoon studio in New York

1916

Pioneering animator Max Fleischer is granted the patent for the rotoscope and uses the process to trace live-action film of his brother to create Out of the Inkwell

1917

The world’s first animated feature, El Apóstol, is released in Argentina

The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918)

1918

Winsor McCay creates The Sinking of the Lusitania, an important milestone in the use of animation to create propagandist film

1919

Paramount Pictures release the animated short Feline Follies

1920

The Debut of Thomas Cat becomes the first recognized color cartoon

1921

Walt Disney begins to create popular animated films for the Newman theater chain in Kansas City

1923

Disney merges live action with a cartoon in Alice’s Wonderland

1925

Scottish inventor John Logie Baird transmits moving silhouette images, the forerunner to modern television broadcast

1926

Using cut-out silhouettes, German-born animator Lotte Reiniger completes the feature-length Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed (The Adventures of Prince Achmed)

Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed (The Adventures of Prince Achmed) (1926)

1927

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is founded

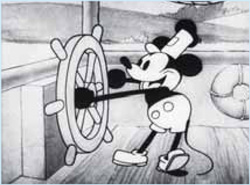

Steamboat Willie, 1928. © Disney

1928

Steamboat Willie, starring Mickey Mouse, becomes the first Disney cartoon to feature synchronized sound

1929

The first of 75 animated shorts known as the Silly Symphonies, The Skeleton Dance, is animated by Ub Iwerks, Disney’s partner at Walt Disney Studios

1930

Betty Boop makes her first appearance in Fleischer’s Dizzy Dishes. In France, Starevich’s Le Roman de Renard (The Tale of the Fox) becomes the first feature-length puppet animation

Betty Boop (1930)

1932

Disney releases Flowers and Trees, the first known Technicolor cartoon (in three colors)

1933

Willis O’Brien produces his stop-motion gorilla for King Kong. The Three Little Pigs premieres, the first Disney film to suggest animated personality and to be originated on storyboards

1934

Donald Duck is introduced to cinema audiences in the film The Wise Little Hen

Komposition in Blau (Composition in Blue) (1935)

German Oskar Fischinger makes the abstract animation Komposition in Blau (Composition in Blue)

1936

The BBC broadcasts the first high-definition television service from its transmitter at Alexandra Palace, London

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). © Disney

1937

Disney releases the epic Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the world’s first full-length, sound-synchronized Technicolor animated film

1939

Gulliver’s Travels, created by the Fleischer studio, becomes the first film to challenge Disney’s monopoly on cartoons

1940

Disney releases Pinocchio and Fantasia but both are surprisingly poorly received by audiences. The first Tom and Jerry cartoon is created and released by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera

1941

The Walt Disney Studios strike is a painful episode in the company’s history. In China, Wan Laiming and Wan Guchan produce the animated feature film Princess Iron Fan

1942

The epic feature film Bambi is released by Disney

1944

The birth of the United Productions of America (UPA) studio. The Gaumont British animation studio is originated in Britain

1946

The controversial Song of the South, a version of the Uncle Remus stories, is completed using a mixture of animation and live action, but never released

1947

Tintin makes his animated debut in a puppet version of The Crab with the Golden Claws

1948

The feature-length puppet animation The Emperor’s Nightingale is created by Czech filmmaker Jirí Trnka

1949

Fast and Furry-ous sees the first appearance of Chuck Jones’s creations Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote

1950

In movie theaters, Disney releases Cinderella, while Crusader Rabbit is the first cartoon created for television in the United States

1952

The technique of pixilation is introduced by Norman McLaren’s film Neighbours

Neighbours (1952)

1953

In America, Warner Bros. animator Chuck Jones creates the influential Duck Amuck

1954

George Orwell’s novel Animal Farm is animated by John Halas and Joy Batchelor and will become hugely influential

Animal Farm (1954)

1957

Bugs Bunny makes his most famous appearance in Jones’s cartoon What’s Opera, Doc?

1958

The much-awaited Sleeping Beauty is a commercial disaster for Disney and painfully disrupts plans to produce animated features in this genre for more than thirty years. The first color animated feature in Japan, The Legend of the White Serpent (known in America as Panda and the White Serpent), is released

1960

Hanna and Barbera introduce Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble in the animated television series The Flintstones

1961

Havoc in Heaven heralds the beginning of audiences becoming familiar with Chinese animation

1963

Japanese television cartoon Mighty Atom spawns many other Japanese productions. The popular television series La Manège Enchanté (The Magic Roundabout) is created by Serge Danot in France

1964

John Stehura creates the experimental film Cibernetik 5.3 using punch cards and tape

1965

The Czech adult puppet film The Hand is created by Jirí Trnka, and becomes a rallying cry against the repression of the totalitarian state

1966

Walt Disney dies at the age of 65 and never sees the completion of the planned Disneyworld adventure park in Florida. British children’s television sees the arrival of the stop-motion Camberwick Green

1968

The Beatles provide the soundtrack to director George Dunning’s animated film Yellow Submarine

1969

First showing of Sazae-San in Japan, still running today and credited as being the world’s oldest continuously running animated series for television. In Britain, The Clangers land on television, courtesy of Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin

The Clangers (1969)

1971

Sony launches the U-matic system, the world’s first commercial video cassette format in Tokyo, Japan. The first IMAX cinema opens in Montreal, Canada

1972

The video games company Atari is founded

The Wombles (1973)

1973

The Pannónia Filmstúdió, based in Hungary, creates Hugo the Hippo, using some voice-overs provided by singing sensations of the day, The Osmonds. In Britain, The Wombles is created by Ivor Wood at Filmfair, who later creates Postman Pat. The first cellular phone communication is made in New York City

1974

Bob Godfrey’s Roobarb hits British television screens. Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata work together to create the Japanese television series Heidi

1975

George Lucas founds Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) and pioneers the use of motion control cameras in Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. Bill Gates and Paul Allen found Microsoft in Albuquerque

1976

Apple is founded by Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne in California

1977

Caroline Leaf comes to world attention with her vivid portrayal of family bereavement as seen from the eyes of a child in The Street. Ed Emshwiller creates Sunstone, a short computer-graphic film in 3D

Sunstone (1977). Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

1980

Chinese animation re-emerges as an important force with the creation of the film Nezha Conquers the Dragon King

1981

IBM’s personal computer is launched using Microsoft DOS (Disk Operating System)

1982

At Disney, Tim Burton uses stop motion to create Vincent, and Tron heralds the arrival of CGI in major studio productions. Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan becomes the first movie ever to have a completely computer-generated sequence, created by ILM.

Tron (1982). © Disney

1984

Disney attempts to revive its fortunes and prepare for the inevitable demands of the CGI animation onslaught by hiring Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg. Apple launches the first Macintosh personal computer with a mouse and graphical user interface (GUI)

1985

Will Vinton’s important feature film Mark Twain is completed using the technique of claymation

1986

Luxo Jr. becomes an important marker for CGI animation. Its director, John Lasseter, later goes on to direct for Pixar

1988

Hybrid animation and live-action feature Who Framed Roger Rabbit is released. Akira debuts in Japan, directed by Katsuhiro Otomo

Akira (1988)

1989

The character of the Pseudopod in The Abyss is the first computer-generated 3D character. On television Matt Groening’s The Simpsons becomes a series in its own right. Meanwhile at CERN, the European particle physics laboratory, Tim Berners-Lee invents the World Wide Web

1990

ILM develops computer-generated textured human skin for the movie Death Becomes Her

1991

The Ren and Stimpy Show provides some edgy animation for television, created by John Kricfalusi

1992

Welsh television channel S4C commissions the series Shakespeare: the Animated Tales using a mixture of animation processes

1993

Steven Spielberg uses animation in Jurassic Park. The stop-motion feature The Nightmare Before Christmas is deftly produced by Tim Burton and directed by Henry Selick

The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993). © Touchstone Pictures

1994

Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg’s bitter dispute at Disney impels the latter to co-found the DreamWorks studio with Steven Spielberg and David Geffen

1995

Launch of Toy Story, directed by John Lasseter, the world’s first feature-length CGI cartoon. The Wrong Trousers wins an Oscar for Nick Park. DVD optical disc storage technology is developed by Sony, Philips, Toshiba, and Panasonic

Toy Story (1995). © 1995 Disney/Pixar. Mr. Potato Head is a registered trademark of Hasbro, Inc. Used with permission. © Hasbro, Inc. All rights reserved.

1998

Pixar’s A Bug’s Life enters into an insect war with DreamWorks’ CGI feature Antz

1999

Aleksandr Petrov’s The Old Man and the Sea is the first animated film released in IMAX format and wins an Academy Award for Animated Short Film

2000

Aardman Animations begins an uneasy partnership with DreamWorks with the animated Chicken Run

2001

Hayao Miyazaki’s Oscar-winning Spirited Away is launched to critical acclaim

2002

Motion capture is successfully used to create Gollum in The Two Towers. Ice Age is released by Blue Sky Studios

2004

Brad Bird directs Disney•Pixar’s CGI superhero feature film The Incredibles Disney•Pixar’s Ratatouille, directed by Brad Bird, is released. CEO of Apple, Steve Jobs, unveils the iPhone, a multi-touch smartphone that will spawn a generation of applications (apps) that use animated content as a central operational feature

The Incredibles (2004). © Disney/Pixar

2005

Tim Burton’s eagerly awaited Corpse Bride and Nick Park and Steve Box’s The Curse of the Were-Rabbit are released, heralding a new interest in stop-motion animation

2006

Disney completes its acquisition of Pixar. HD DVD and Blu-ray are launched globally, promising unmatched visual output quality

2008

British director Suzie Templeton wins an Oscar for the acclaimed stopmotion animation Peter and the Wolf

2009

Up, directed by Peter Docter, became the first Disney•Pixar feature film to use Disney Digital 3D. Henry Selick’s darkly atmospheric 3D CGI stopmotion feature Coraline is a hit at the box office

Up (2009). © Disney/Pixar

2010

Shaun Tan’s picture book The Lost Thing is adapted into an animated short by Tan in collaboration with Andrew Ruhemann and wins the Academy Award for Animated Short Film