Animation can be used as a vehicle for telling stories, expressing ideas, explaining principles, and selling products and services. With commissioners, creators, and audiences alike becoming aware of its possibilities to reach out and engage with different demographics, so the popularity of animation in different forms has grown. Whatever purpose the medium is being used for, its content is significant. Not all content, however, is drawn from a script. Other visual, aural, or literary starting points may be equally valid, depending on the type of animated production being considered. In other instances, starting points are briefed rather than originated by the creators themselves, again from numerous possible starting points.

This chapter looks at the ways in which animators originate and develop their concepts and ideas and communicate them to the crew, how these are developed and prepared for a pitch, and how the corresponding research is undertaken and used in the creation of the animation.

Elizabeth Hobbs’s touching film, The Old, Old, Very Old Man (2007), tells the story of Thomas Parr, who reached the age of 152.

Concepts and ideas

The content of an animated film, regardless of its end use, has not been simply conjured out of thin air. Content may have been introduced through a script, a brief, an adaptation of a previous work of literature, or from an individual’s imagination, so the origination and development of concepts and ideas may vary.

Concepts have often been thought about, mulled over, and debated long before an idea for an animated project goes into production, or before a series or an ad has been commissioned. Concepts are abstract ideas that need time, research, and structural development to become concrete ideas having form and foundation. In preproduction, the animation team experiment and test countless initial concepts, discarding them or redeveloping them from their original inception to working ideas. However these ideas are ultimately arrived at, they are absolutely vital. They ensure that stories have solid foundations that can be communicated in telling ways or that enable an audience to identify a product or service ahead of its nearest rivals. Perhaps most pivotal of all, these ideas can make the final animated outcome original, distinctive, and memorable. Ideas are the very lifeblood of animation, on which every other ingredient depends, validating and authenticating content for the audience.

Studio AKA has enjoyed commercial and critical acclaim for their output of highly engaging and memorable productions, from independent short films to commercials.

The significance of ideas

As human beings, we are extraordinarily complex and sophisticated receivers of information. Our body’s sensory stimuli are charged from earliest infancy through a mixture of intuition and learned and acquired experiences. We are informed by our ability to observe the world around us. This information is processed, synthesized, and recorded by our brains every second of our waking day and can be recalled later through other experiences that act as triggers to engage our memory. An important part of our collective makeup is our ability to interact and communicate by sharing these stimuli with each other. Human social abilities are very advanced and are perhaps something we often take for granted in our everyday lives, but they are fundamentally important to the way in which humans co-exist in a fully functioning, inquisitive, and progressive society.

Animation uses two critical sensory functions—sight and sound— as primary drivers to communicate what the creator wants us, as an audience, to perceive, fusing them together to create an emotional experience. In simple terms, this might be best illustrated by imagining a script as a series of words on paper voiced by an actor and a sequence and series of lines on paper drawn by an animator. The important connection is made by a director, who encourages these forms in parallel with each other and blends them together as one, giving the production its shape, life, and function. The audience sees a synchronized and coherent form that is imbued with emotions directly connected to their own experience as individuals and which encourages parts of their brains to validate, authenticate, and believe the content.

Investing in ideas

Core narrative or conceptual animated ideas can have a sensory effect on other parts of our human psyche. They allow us to become emotionally attached to characters, stories, and events, sharing in celebrations and achievements as well as commiserating with failures or recognizing weaknesses. The very nature of the dynamism, vibrancy, and clarity of ideas demonstrates that they can make us feel something for the subject being portrayed. In turn, this ability for animators to touch our lives through their work makes an audience feel intrinsically connected, helping them feel valued as participators in the animation process, rather than merely acting as recipients. It is this reciprocal arrangement that has endeared animation to many fans from childhood, and which creates the opportunity for the medium to be used outside of “traditional cartoon” territories by expanding into more adventurous realms, such as the animated documentary or information graphics.

Nick Park’s The Wrong Trousers (1993) sees the villain, Feathers McGraw, captured and imprisoned in a zoo as his punishment for attempting to commit a diamond robbery.

Indeed, animation relies heavily on the power of individual and collective memory. On the one hand, an animator’s ability to call on the power of recall means that connections can be established, frameworks built, and foundations set for the introduction and development of ideas. On the other, an audience’s ability to recall some memories and not others, or to remember sequences or orders differently, enables animators to play with our recollection. Such reconstitutions and reconstructions of events scramble our memory, allowing a “suspension of disbelief” to become possible and trick our minds into seeing something that seems plausible. It is possible for these shared memories and events to have the same basis in reality for everyone, but for individuals the experiences, knowledge, and expectation that contextualize how they recall such occurrences can mean that memories differ considerably. This permits the creator a license to play, be liberal or economical with the truth, and blur the boundaries between fact and fiction. Examples in animation history are numerous but are well illustrated by many of the visual gags that appear in the Tom and Jerry shorts, where visual metaphors illustrate punch lines that happen to one or other of the characters at the end of each visual joke. For example, Jerry placing an iron into the chasing Tom’s path inevitably means Tom collides with that object and is portrayed with a face shaped like the footplate of the steaming iron.

Starting points

Animation does not exist in a vacuum, but borrows inspiration from real world events, contemporary culture, and different aspects of our lives, much as other art forms do. Successful animation acknowledges that it co-exists with and contributes to a world of visual culture and popular entertainment, and that these are vitally important and culturally rich parts of our human existence. It also adds to, as well as learns from, parallel art forms and often uses influences as important core strands of new projects and initiatives. Good ideas stem from keen observation coupled with a need to communicate these observations to others. The ideas need to be exhibited in ways that can be understood by both the production team who will create them, and by the audience who will receive them. The animator’s job at this point in the project is to make these ideas a visual reality.

The starting point for an animated project can grow from a variety of interests—including commercial, industrial, educational, informational, or personal—informed by both creators and commissioners. As it is a form that draws interest from such a broad spectrum of participants, the decision to use animation as a form of expression originates from one or more of these points. Consequently, there is no one single way in which an animated project is born but, broadly speaking, some of the more traditional starting points include scripts, pilot episodes, or commissioned briefs that require specific animation treatments. It is equally possible, however, to create a production based on artistic responses to observations and found visual and sonic material. Any of these starting points triggers conceptual thoughts of how to address subjective, structural, and technical concerns and requires some thought at first about how to approach the project.

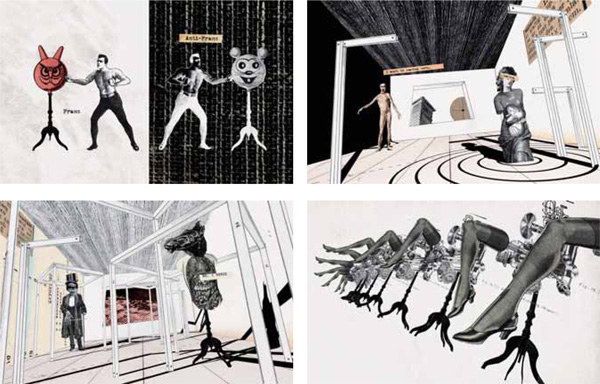

Swedish director Jonas Odell’s striking video for the band Franz Ferdinand actively acknowledges cultural references from historical Constructivist posters and propaganda.

Early conceptual interests can be supported and enhanced by scouring newspapers, magazines, reference books, and online blogs, forums, and podcasts, at home, in the studio, at the library, or out on location. Collected material needs careful reviewing, editing, and storing to make sure that historical and contemporary information has a currency that is both valuable and accurate. This supporting evidence helps to firm up concepts and rationalize them into more formed ideas that can be visually explained to others in the crew who will be working on the project during the preproduction phase.

At the same time, conceptual material must be checked to ensure it is sufficiently accessible for further study and not bound by legal or moral restrictions. For example, it may well be possible to use actual existing factual or fictional tales as a starting point, but then to alter certain events to change the story according to the creator’s wishes. Animation as a form is historically able to weave a rich and varied tapestry in regard to adapted stories, for example the Walt Disney Studios’ 1937 adaptation of the classic fairytale Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Halas & Batchelor’s 1954 adaptation of George Orwell’s novel Animal Farm, and Jimmy Murakami’s 1986 adaptation of the Raymond Briggs graphic novel When the Wind Blows. All three examples are written in a way that exudes a visual richness, and the animator’s task in each was to preserve the spirit of the original text while adapting the story to an animated context that articulates the plot (and associated subplots) through artificial sequential vision and sound.

John Halas and Joy Batchelor review early Animal Farm layouts.

Ultimately, successful starting points should strike a chord with the creator, depending on the project in hand, and allow the audience to sense it quickly. For example, nostalgia and familiarity are signals to which audiences naturally respond favorably, regardless of their racial, cultural, linguistic, or religious differences. Given the global nature of animation as a form, it is sometimes necessary for creators to strike a balance in creating work that acknowledges differences and at the same time makes audiences feel included and valued. This requires that ideas are tested and adapted to counter criticism that they favor one section of an audience by marginalizing another.

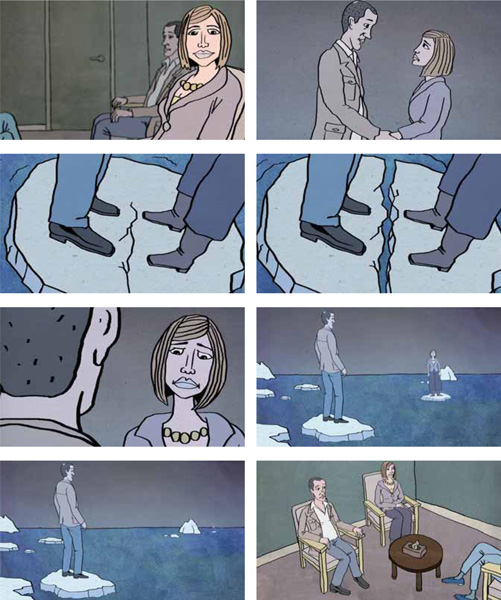

Nonetheless, it may not always be possible to satisfy all audiences all of the time, and many critics and fans of animation argue that there are good reasons not to homogenize animation content, but rather to celebrate our individuality and differences. Indeed, region-specific work such as Ari Folman’s universally acclaimed Waltz with Bashir (2008) can help us better understand the culture and customs of different parts of the world that may be unfamiliar, even though we might not agree with some of the actions being shown.

Ari Folman’s absorbing feature film, Waltz with Bashir (2008), serves as a timely reminder of the power of animation to traverse boundaries of race, religion, culture, and language, presenting a difficult subject matter through a deceptively simple technique.

Developing a conceptual framework

Animators use conceptual frameworks to contextualize the script, brief, or imagined starting point of the project. A conceptual framework encourages, informs, and permits the shape, definition, and progression of each phase of the production. It allows the crew involved to measure their progress and evaluate their individual and collective achievements, and also enables them to bring ideas to the table and to test, evaluate, and revise the project effectively.

Pixar’s purpose-built studio in Emeryville, California, offers a dynamic and stable environment to create animated feature films, with creative studio environments housed under the same roof as huge render farms processing the computer-generated imagery. © Pixar

The conceptual framework should establish a series of parameters that are understood as being guiding principles by which the project is defined and then conducted through the preproduction and production phases. It should include answers to the following ideological and practical considerations:

• What is the starting point for the project?

• What media format is the work likely to take?

• What style or animated treatment is required for the project?

• What is the role of the audience in the production?

• What is “possible” or “impossible” in the story?

• What restrictions are there in terms of subject matter, handling, association, and/or implication?

• Are there any moral, ethical, or ideological restrictions to the subject or the intended depiction of the subject?

This is not meant as an exhaustive list, but instead an illustration of contextual guidance that might permit the subject to be considered objectively and freely.

The studio environment

A good studio environment is important in supporting the schedule, workflow, and conceptual framework of an animated project. Any studio must have consistent and reliable conditions that will support the changing needs of the project. It must be able to be secured, but equally should be easily accessible to those who need continual access. Ideally, the studio will provide a solid base for extended working practices, as the process of animation is time-consuming and meticulous.

A flexible studio space should be conveniently located for both the animator and visitors to the studio. It needs to be well-resourced, spacious, temperature controlled, and capable of being adapted to provide different lighting conditions. The studio must be insured and should also conform to health, safety, and fire requirements, especially where it is part of a bigger building, and occupants are responsible for ensuring that published local guidelines are followed. Working conditions are checked regularly, and it is helpful to have an inventory of equipment and materials that can easily be checked by inspectors looking for assurance of compliance. Many studios also have a register to prove who is working at particular times and visitors are also closely monitored.

A welcoming and inviting environment, encouraging playful thought and the exchange of ideas around the animated project, is the ultimate goal. It should be remembered that the space is considered a home from home by many of the crew. An inviting studio is a place where animators will be happy to spend long passages of time producing quality work; the layout should enable the team to work closely as a group in a shared space, but have enough flexibility for partitioning off the space when members of the crew need to work independently.

Toronto-based animation production company Head Gear have created welcoming, conducive working environments to allow their animators to work in comfort.

The success of the layout, the maintenance of the studio, and the lively atmosphere of the space can also actively encourage other supporting activities. For example, the ability to identify, develop, and enable acting to occur to inform animation is a fundamental expression. This can be achieved through a variety of non-verbal activities, including the depiction of exaggerated or understated movement, body language, and figurative gesture. Many animators come from a background that is steeped in the understanding of the art, science, and even politics of movement, through drama, music, and dance, and use this knowledge and experience widely and frequently in their work. The studio environment needs to have sufficient space and resources to allow such actions to occur.

The ability to act is often employed by animators to explain their concepts and principles to other members of the crew in the studio environment. These structured or impromptu sessions are useful in helping the team to identify common ideas, explain concepts where other forms of communication are not appropriate, and share a vision of how problems concerning the depiction of characters, environments, and situations might be solved. Very often they also save time and give a clearer picture of the overall essence of a visual idea.

It is important to turn abstract concepts into visible ideas. Animators keep a mixture of journals, sketchbooks, and notebooks to record their observations and thoughts, processing this information through drawn or noted ideas. This documenting process is highly personalized and individual, helping to articulate and place events into understandable visual interpretations.

The value of drawing

The immediacy and interpretive nature of drawing allows the playful exploration of ideas and can lead to some surprising discoveries. In turn, these events can formulate new directions for subject matter to take that audiences might not expect. Visual documenting is often highly engaging, and can range from expressive depictions of scenes or situations, right through to detailed working out of figurative poses or explanations of mechanical devices. It can be representational, exaggerated, or abstracted. It can also be conscious or subconscious—depending on the creator’s need or desire. Animators such as Joanna Quinn, Caroline Leaf, and Elizabeth Hobbs all prolifically document discoveries through drawing and this ability to explain and define movement through drawn statements extends as a central identifying theme in their work.

A bewildering array of mark-making materials, processes, and techniques, at different scales and on numerous surfaces, can be employed to capture thoughts and observations, depending on the type of activity the animator wishes to record. For example, the fine point of a pencil might be better to explain details in a sketchbook, while the broad sweep of a chalk pastel perhaps better enables the animator to capture a sense of movement on loose sheets of paper. Whatever is being recorded, bringing tools that are fit for purpose is essential and prior preparation is key.

The fluidity of Elizabeth Hobbs’s drawing aids figurative and gestural interpretation with an economy of visual marks, encouraging the audience to “see” the story unfold.

Animator’s tools are highly specialized, depending on the task in hand.

A typical treasure trove of drawing materials for animation preproduction might include:

• various grades of graphite pencil

• sharpeners and files (nail files are good for getting very fine points)

• selection of erasers (including putty, which can be shaped)

• graphite sticks

• charcoal (various grades, including compressed)

• fixative

• compass

• scissors and cutting blades/handles

• colored pencils

• felt-tip pens and markers

• watercolor and/or gouache paints

• colored waterproof inks

• pastels (oil, wax, and/or chalk)

• brushes (a broad selection might include flat and round heads, hog- and sable-haired, long- and short-handled, and possibly specialist variants, including Japanese calligraphic brushes, to suit specialist work as required)

• dip pen with selection of different nibs

• selection of fine liners

• ruling pens

• measuring aids (set squares, rulers, protractors, French curves, and so on)

With the increased use of digital technology, it has become commonplace to mix recording tools to capture specific observations. For example, a sketchbook can be used to note specific details as drawn information— perhaps to understand how something works—while supplementary digital photographs can provide a consistent contextual overview of the subject in question. Sometimes digital photographs allow an instantaneous moment to be captured that would be difficult to report through a detailed drawing. This versatility simply gives the animator greater tools on location to be able to consider observations and capture the necessary recordings. This enables informed judgments to be made in a detached environment, where it is possible to be objective about the quality of collected information.

The following suggested toolkit can be supplemented by your own particular requirements, depending on the specific area of animation you are working in:

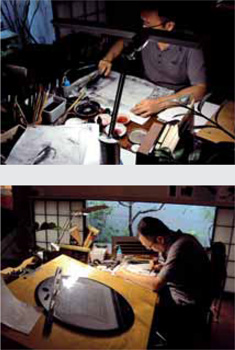

Influential Japanese animator Koji Yamamura at work in his studio uses a mixture of analog and digital processes to make his independent films.

• sketchbooks (various sizes, types of paper, and bindings to enable the animator to record observations)

• notebooks (again, of various sizes, as preferred)

• elastic bands or clips—useful for securing pages against prevailing weather conditions

• large sheets of paper—to draw expressive movements or to expand ideas where a sketchbook is inappropriate

• digital camera(s)—a compact camera is essential, but an SLR camera with manual focus is probably more desirable as it can be customized with different lenses and filters; choose the best picture resolution capability you can afford; the option of shooting movie frames is also extremely useful; a memory card with good storage capacity is a must

• removable hard drive (again, buy the most storage space you can afford)

• tripod

• drawing stool

• sturdy bag

• travel umbrella

• waterproofs (can save time and allow you to work uninterrupted)

• freezer bags—useful for keeping collected material or equipment dry and with a zip seal that can be reused

• a digital sound recorder

• external microphone

• headphones

• watch or stopwatch

• duct tape—waterproof and reliable

• repositioning tape

The central issue is to be methodical and to have a structure and order to the information being collected first-hand. For example, some animators use a personalized wall planner to record events and store associated material. Others prefer to collate material digitally, using tools such as digital data-tagging technology to pinpoint related observations and group them together. For example, Apple’s iOS software uses face recognition technology to group photos of people together, borrowing the digital profile of where the photo was taken to create a visual footprint of this information as a pin in a map. This allows a hierarchy of information to be developed, at the same time ensuring that all the information is kept in a versatile format that can be viewed according to the creator’s preferences.

The value of the doodle

Doodling in particular, while seen as trivial and banal by some professions, is highly prized by animators as a way of potentially unlocking closed mindsets and encouraging playful intercourse between images and sounds. The word “doodle” is thought to originate from the verb “to dawdle,” implying a lazy, haphazard approach. Doodles in this context can be read as unfocused drawings, often made while doing other tasks. Various scientific investigations indicate that while the brain is concentrating on one function, it also has the capacity to allow additional motor skills to occur, such as drawing or scribbling, without the creator being fully aware of his or her actions.

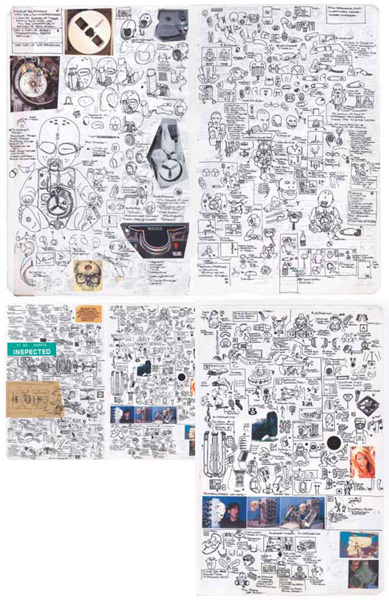

In the very early stages, doodling ideas is a very productive way of allowing the flow of ideas to develop.

Doodles can be representational, abstract, or symbolic and can be created anywhere, at any time, and with limited materials. Their universality is part of their appeal and disarming nature, turning some who express reservations about creativity into creators. The ability to express oneself without the fear of failure makes the doodle a priceless commodity, instantly able to illustrate random thoughts that might lead to a string of sequential images that ultimately could form the basis for a plot. Doodling marginalizes risk, throws out conventional representational rules, and encourages the impossible to become realized—echoing the ability of animation itself.

Idea development

As a form that privileges motion, animation is able to explain, articulate, and celebrate artificial passages of time. Some ideas can use time to alter appearances, suggest events, or change meanings, and this quality is used by animators to progress the development of plots, characters, and scenes. The working up of initial thoughts through a sequence of associated or related images allows scope for expansion or condensation, introducing possibilities and raising issues that need to be addressed for the project to continue to flourish. Several leads can be pursued at the same time to find the best solutions. Connected sequential visuals also start to suggest main points of actions for ideas that could later become key frames in the project. Some animators work quite loosely in this regard, while others, typified by Johnny Hardstaff, work intensively, meticulously working through the best ways to squeeze meaning out of every element of the project.

Ideas in motion through the figure

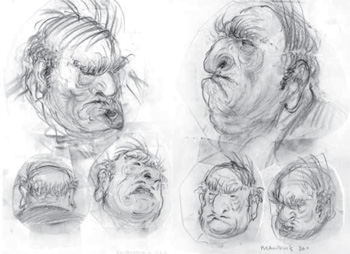

One of the most important aspects uncovered in ideas development is that of depicting the movement of the figure, where certain poses can communicate powerful symbolic statements and act as signals that the plot is developing in a particular direction. In order to fully understand, appreciate, and articulate motion, a thorough understanding of the construction of the human figure is important. This is fundamentally achieved through observing and recording figures from life, through drawing, exploring the anatomy of the human form in both static and moving poses, whether nude or clothed, male or female, young or old. Animators place great store in their ability to understand how the human body moves, balances, and rests. This ability to comprehend the body’s capabilities and restrictions has a direct impact on characters they go on to create. Physically imitating motion through acting or miming is also often employed to help understand the complexities of movement.

Johnny Hardstaff’s obsessive sketchbooks show a microscopic attention to detail as he works through ideas.

Characters need to move in ways that audiences will believe and accept. For example, the main character in Peter Docter and Bob Peterson’s Up (2009), Carl Fredricksen, is an unlikely seventy-eight-year-old lead. His restricted movement is painstakingly captured by the team of animators from the Disney•Pixar studio—who drew countless elderly men in an attempt to understand how the ageing process affects the general properties of movement and posture of the human form—right the way through to how the character wears his clothes, how his skin ages, and generally how his body language differs from that of a growing boy or young man.

Aids to developing ideas

Animators need to test and evaluate ideas in motion to gauge how successful they are. Several devices are available to showcase convincingly idea development through movement. On a basic level, flipbooks, character study sheets, simple armatures, and line tests can be employed to depict and test basic movement. As ideas for characters or sets get more involved, working on a bigger scale, with the option of being able to trace or overlay drawn image elements, is useful. This bigger scale promotes the choice of scale and gesture and also allows work to be pinned to boards, creating an opportunity for ideas to be shared. Building quick models, often very roughly, allows ideas to be realized and developed and has the added advantage of allowing the animator to start thinking three-dimensionally, especially if the production method is going to follow this process. Sequential images can also be scanned or photographed in order, and played back at different speeds to give an indication of the “start” and “end” of an idea.

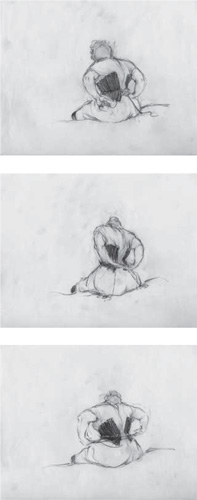

British independent animator Joanna Quinn is known for her sensitive and acute portrayal of the human form, demonstrated here through drawn studies for Elles (1992), which pays homage to Toulouse-Lautrec.

The flipbook was invented by John Barnes Linnett in 1868, and has become a relatively quick and simple sequential device for transferring two-dimensional static images into short moving sequences at relatively little cost. Like the zoetrope and the praxinoscope, they are very useful to test out ideas on others but, unlike those cylindrical devices for viewing images in motion, flipbooks have the advantage of being linear in format. This allows animators the opportunity to take doodles and sketches of ideas and develop them as a linear narrative. The “movement” is created by flipping the pages quickly so that the single images appear to move as they are pieced together by the brain to make a sequence.

Flipbooks should be no bigger than 4 x 6 in. (10 x 15 cm) and no smaller than 2 x 3 in. (5 x 7.5 cm) and should contain at least fifty pages, allowing the page to be seen as one whole entity, but also offering sufficient workspace for the drawings. Each page becomes a blank canvas and, using the previous drawing as reference, the animator has the freedom to explore the properties of the page by making subjects morph from one scene to another, playing with spatial and composition elements to speed up and slow down the story.

The size restrictions mean the pages of the book can be flipped quickly but consistently and this is key to smooth transitional movement. The outer two-thirds of each page are visible (the inner third is consumed by the binding and the operator’s thumb securing the book in place). The separate sheets of paper are bound together tightly, allowing the pages to be flipped. The story can run in either direction, but pages have a tendency to “arch” running front to back and make the story harder for the viewer to follow.

These gestural studies reveal both Joanna Quinn’s knowledge of the human form, and the possibilities for using the character as a vehicle for introducing ideas and establishing mood.

The arrival and abundance of digital technology has revolutionized idea development and testing. Digital cameras, camcorders, cell phones, motion-capture technology, and even some PDA devices all have the facility to record movement and to allow instantaneous playback. They have the benefit of allowing animators to examine footage repeatedly at different speeds and resolutions to understand how motion occurs. This knowledge can then be applied to thinking about how the production could use specialist animation processes and techniques to communicate these ideas to the audience.

These visual ideas can take on an extra dimension with the introduction of sound. If ideas are being produced in response to a script or brief, it is possible to read and record passages of spoken word to provide a framework or backdrop to test ideas against. Even odd sound effects recorded on location, or found from other sources, can be helpful in bringing visual ideas to life. Marrying sound to image is important and many animators argue that the sooner this occurs the more seamless and natural the final result appears (see page 124).

The ability to express initial ideas clearly is very important. As animation is artificial, it is entirely possible to create imagined worlds that are unfettered by the limitations of our own physical one. Provided that such imaginary conditions are credible to the audience, animators aim to achieve a harmonious and balanced overall feel, even if certain components are fantastically imagined or seemingly unbelievable. This requires that the animator has a full knowledge and grasp of the synchronicity between the structural elements of color, composition, design lighting, and movement that make up the single frame, in order to communicate a consistent and collected statement of intent. At this phase of preproduction, the most important requirement is to ensure that ideas are strong and flexible enough to act as a foundation to build these other elements from. The essence and flavor of the overall body of work is critically important, allowing characters, scenes, and events to work in harmony, aiding believability for the audience. Time spent working ideas through is important and should not be overlooked.

Evaluating ideas

Good ideas are not set in stone, but instead need challenges to test their authenticity, believability, and currency. Sadly, there is no magic formula for a good idea. One might argue that good ideas stand more chance of materializing from a process that encourages thorough research, excellent preparation, and an ability to construct interesting, dynamic, and thought-provoking content. Ultimately, however, there is a strong element of chance involved in animation, which reveals its experimental properties and perhaps is part of its charm for creators and audiences alike.

While the element of chance equals risk in some quarters, the animation process at least enables some degree of certainty and reassurance by its nature of being an artificially constructed medium. In the preproduction stages, where changes can be more significantly made and cause least disruption, ideas are tested and developed. They can also be shelved or rekindled. Changes made outside of the preproduction or production phases are inevitably more time-consuming and expensive and may prevent the work being completed.

Learning to pitch ideas is a necessity and is regularly practiced through college critiques as a way of building confidence and sharpening students’ presentation skills.

An honest and open review of ideas is essential to iron out weaknesses in preproduction. It is important to seek balanced but insightful reviews at opportune moments. These vary, depending on the nature of the project, but might include:

• initial ideas generation process

• a rough storyboard introducing the core key frames of the production

• an overview of the central characters

• ideas about locations and sets

• the visual breakdown of scenes

• completion of the rough animatic where the project is seen sequentially for the first time

Many larger studios have the luxury of screening developing ideas to selected audiences (often their own staff), who have often had to sign agreements preventing them from talking about work being undertaken. Ideas can be explained and measured and comments noted, digested, and acted on. If the work is commissioned, there will be an agreed process of review that has already been built into a schedule, so that key individuals, such as marketing and account handlers, can satisfy themselves that the company is being profiled in the correct way and the budget is being run efficiently. For more personal projects, an ideal review team might consist of individuals who have an interest in the project—perhaps as other animators or as keen watchers of animated productions—whose opinions are valued, based on previous knowledge, experience, and expertise. Receiving friendly criticism is not helpful when trying to produce the best possible work and should be avoided.

Honest criticism can sometimes be painful, especially where a project has been nurtured over a long period of time or if the subject matter is highly personal. It is important to remember that the evaluation process is there precisely to allow ideas to be tested. If a reviewer does not understand something, it is likely that a movie theater full of people will not either, so it is better to deal with any issues at the beginning. The important point to take from the review is what does not work and why, and then to ascertain whether issues are conceptual, structural, or to do with poor explanation. Understanding the faults allows the animator to take stock of ideas or sections of the project and reconfigure them.

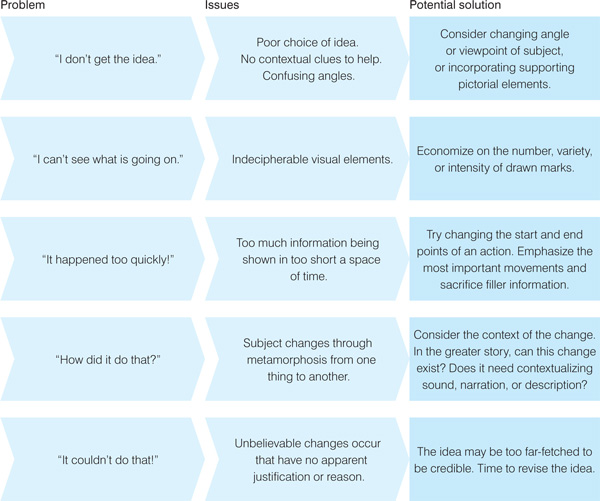

Below are some likely issues that animators may have to face when developing ideas:

Pitching concepts

Unless the animated project is self-funded or is an independent production, ideas will usually need to be communicated to an outside agency through a “pitch.” A pitch is an overview of the planned production and will clearly vary depending on the scope, format, and outcome of the work. A feature film will require a series of pitches, as will an advertising campaign, while a short feature will normally be pitched only once. Traditionally, pitching has involved the meeting of constituent stakeholders of the production in the same place to hear about potential ideas and directions for the project. In recent years, such meetings have also been conducted virtually if required, with the improved reliability of online and mobile technology better able to connect parties in different venues and countries.

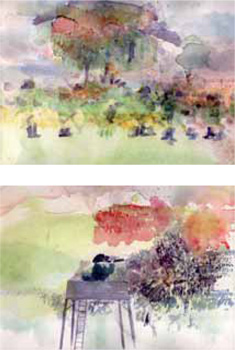

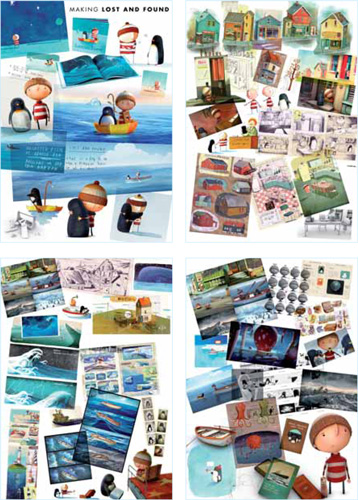

These images show the background research required to adapt a children’s book to screen, including ideas for possible environments, creating scenes for action to occur, and planning compositions to heighten a sense of drama.

As a summary of the project, the pitch should easily and quickly identify the core idea of the production and indicate the target audience. The pitch should clearly mark the beginning, middle, and conclusion of a story and might seek to do this through a written treatment, a series of visuals, a short sequential piece, or a mixture of these formats. Whatever the format the animator decides to employ, the critical point is to establish the idea clearly, concisely, and memorably, taking into account that individuals who make up the group might not be fully visually literate or may not have direct understanding of the possibilities of the animated form, but they may have full control over future funding of projects.

The individual or team involved in introducing the idea should plan the pitch in advance, consolidating the body of material into digestible and memorable pockets of information that directly address what they have been briefed to do. If necessary, such material as supporting folios of visuals, examples of treatments, and display maquettes can be expanded upon through further questioning, where answers might employ these examples to persuade or validate previous information given in the original pitch. A practice pitch establishes what combination of materials the pitch is using and the length of time the presentation will take, and allows the team to prepare for likely questions by working out potential answers in advance.

Good character design is cemented through rigorous and painstaking attention to detail, as demonstrated by Clyde Henry’s extraordinary stop-motion film, Madame Tutli-Putli (2007).

Research

If ideas are the lifeblood of animation, then research is the crucial oxygen by which those ideas have the chance to come to life. The importance of research in preproduction cannot be stressed enough, though it is occasionally overlooked as its outcomes cannot be immediately tangibly identified when an animated project is released. However, if we begin to unravel the gloss of the final product, it soon becomes apparent that research is wholly evident in every work and exhibited in the quality of content in a film or series. To examine animation further, we must begin by asking what exactly constitutes research, how it is collected, recorded, and measured, and how it can be employed to create content that is believable and compelling and that provides a solid foundation on which to build other convincing aspects of the production.

What is research?

For animation purposes, research embodies the process that identifies, collects, sorts, and processes reference material that has been gathered by direct and indirect sources so as to fully understand the concepts behind a story or factual event. In the field of animation, this span can range enormously: from the enthusiastic individual animator who often goes to extraordinary lengths to collect material to convince a commissioning body, the rest of a production team, and the audience about the merits of a particular idea, through to the teams of researchers working on particular aspects of a studio feature film.

Inevitably, there is a particular set of skills associated with this kind of activity. Some people entering the field find themselves drawn to researching projects as they naturally have these specialist skills. Such skills include:

• a love of finding out about subjects that you may not have a direct interest in

• a tenacity and rigor of approach

• an ability to frame questions likely to get informative answers

• an orderly and methodical procedure for deciphering findings

• an ability to catalog outcomes in ways that enable others to access material from different points and for a range of uses

Clearly, an individual researcher needs to have or develop these skills in abundance, together with an ability to manage these activities to a set timescale.

Research is used at different stages of the animation process, and can be returned to at any time for greater clarity, reassurance, or accuracy. This is especially important when dealing with factual subjects, or adaptations of other people’s work. It may also encompass more widespread factors, including researching potential film locations, specialist animators who may be required to perform specialist tasks, or potential distribution regions. Specifically though, research in preproduction is centered around the following areas:

• the preproduction cycle of story research

• historical and factual accuracy

• costume details

• location details

• accents

• mannerisms and colloquialisms

• character interaction

• environments

• audience

• how material is likely to play to different geographical, racial, cultural, or religious audiences

In order to make this process meaningful and relevant, it is vital that the research team share the plan of how best to acquire this information and how the findings of the research process can aid the production overall.

Collecting accurate reference material

Quality reference material is crucial to the origination, development, portrayal, and acceptance of an animated production. Many animators cite the importance of content and will go to extraordinary lengths to satisfy their own curiosity, knowing that well-researched material is the cornerstone of their production and that it might be relied upon by others in the creative process. For example, for their Clyde Henry Productions short film Madame Tutli-Putli (2007), creators Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerbowski spent months investigating how to simulate the ageing process of clothing by first researching the costumes required for their villainous characters, constructing the clothes accurately to scale, and then burying them in mud for several months so that they would take on the patina of aged distressed material. Accuracy is paramount to the success of any piece of animated work. Researchers and animators diligently trawl for large amounts of information and sift this down gradually into identifiable and usable material that has relevance and practical benefit for others accessing it. Clearly, the need for different levels of accuracy fluctuates with the kind of animated project being undertaken. Material that has been poorly referenced often manifests itself in unconvincing and badly conceived ideas that reveal a lack of fundamental preliminary detail when the work is screened.

A lack of preparation can have the potential to mar good scripts, characters, plot lines, and other constituent parts of a project by suggesting a lack of accuracy, rigor, and even belief in the project. To prevent these unfortunate occurrences, a team needs to ensure that the research process involves checking that material has been cross-referenced against other reliable sources to verify key facts, dates, and other immovable information. This can often best be achieved by presenting the collected research in an understandable format to trusted external experts, such as educators, psychologists, and health workers, who can offer helpful and knowledgeable advice.

Identifying and formulating a research methodology

Before embarking on a research agenda for the project, it is important to ask some meaningful questions in order to identify and plan an appropriate method to collect useful material. Each project may require different research methods to explore, unearth, and discover vital information, but it may be helpful to ask the following general questions:

• What findings are likely to be required and what is the best possible way to achieve them?

• How much time is available in the proposed project schedule?

• How physically close and accessible is the research field that has been identified as needing investigation?

• What monetary and/or physical resources are available to the project to collect and compile material into a recognizable format that will positively benefit the team?

• What proportion of available time will need to be designated to collating, sifting, documenting, and archiving the information?

Answering these questions enables researchers to formulate an outline research methodology and plan how the collected material will be assembled as a tangible and usable body of evidence for the creative team to utilize efficiently.

Jonathan Hodgson’s drawn sequences for the BBC documentary, The Trouble with Love and Sex (2011), produced and directed by Zac Beattie, uses a mixture of video recordings, interviews, and video diaries that had been specifically researched to collect audio clips capable of being interpreted into an animated documentary.

Primary research trawl

• visit locations

• establish contact with local experts in the subject

• advertise your presence and explain to people why you are researching the subject and what you are hoping to find (if allowed)

• visit libraries, museums, archives, and collections to check reliability of and access to source material

• make connections with people able to offer personal insights, experiences, or recollections that constitute first-hand research

• keep a diary of meetings, events, and locations visited

• ask to be kept informed of developments in the subject being researched via email or telephone

• collect, tag, and record where research material was collected

• establish any factors that would prevent the use of certain materials in the project

• inform the research team of your findings and prepare them for the amount and location(s) of material to be inspected

Secondary research trawl

• revisit locations if appropriate

• check local contacts for updates on information

• meet contacts and record their observations or recollections

• borrow, read, and record specific information from established sources

• revisit diary notes and look to organize second meetings with interested and informative parties

• check on developments in the subject

• revisit collections of materials and apply questions formulated from the primary research evaluation meeting

• check that permissions have been granted for material you wish to use, including any rights releases, and ask contributors to sign to confirm they understand the full implications of this material being used in the project

• keep connected with the research team and ensure that news is communicated in good time

Tertiary research trawl

• check local contacts for final updates on information

• check clarity of factual information with contacts and record their revised observations or recollections

• revisit diary notes and check that meetings with interested and informative parties have been completed

• check permissions status of research material

• thank those who have helped the process and remain in touch with key providers

Collecting and appropriating research

Wherever possible, it is highly desirable to collect first-hand research material as this greatly improves both the accuracy and the legitimacy of the research. First-hand research might include such activities as site visits, trips to visit local or foreign locations and places of note, interviews with knowledgeable parties, and the canvassing of opinions from individuals or groups who have had immediate dealings with the subject. Time spent preparing for research visits should be built into the project. Researching, locating, and communicating with foreign contacts who know the local conditions inevitably saves valuable time and money on the ground. For international visits, translators are well worth investing in as they will save a good deal of time and effort, and may be able to ask questions of subjects that can turn up further important discoveries.

Of course, it is not always possible to get detailed factual accounts, either because they do not exist in a format that can be relied upon, or because they have been affected by forces such as time, loss of memory, and other developments. In this instance, the collection of relevant secondhand material becomes important and will include archived static media, such as newspapers, magazines, journals, periodicals, and transcripts, as well as broadcast media including old television and radio programs, plays, documentaries, and so on. Successful research involves getting a sense of the context of a story or event, as well as the correct facts about the story itself. This context will add to the atmosphere in which the assembled collection of material will be viewed back in the studio and will also imbue the subject with a sense of authenticity.

Since animators use a great number of starting points in their work— ranging from working from a script or storyboard through to responding to a piece of music or a chance observation—the breadth and depth of research material is essential. To get such scope requires several phases to identify which pockets of material are valuable and which should be discarded. This process is, of course, affected by the time permitted. It may also be appropriate to return to a research field to collect other kinds of material to further consolidate and support material collected on a previous expedition, in line with the research plan set out in the project’s conceptual framework.

Reviewing the research

Research should be collected and collated principally for the rest of the team to understand and use in their work. In preproduction, it is quite common for idea development to overlap with the collection of research material. It is, therefore, crucial that shared information is presented clearly and concisely. This will differ depending on the format of research material collected, but can include pinning drawings, photographs, and collected samples to studio walls, creating a specially designated space within the studio for materials and artifacts to be seen and shared, and using appropriate sound or projection equipment to share recordings or footage with the rest of the team in a screening room.

Julia Pott uses drawing as a way of recording the research around her subject matter for the film Belly (2011), working her findings into the development of characters and situations to create depth and complexity.

Key information is considered at different stages of the preproduction and production phases, but it is important that research reviews are regularly conducted to ensure that collected material is historically, factually, or fictionally accurate. This should be built into the conceptual framework for the project so that everyone is aware of how the material has been collected, sifted, and made available for use. Additionally, studios may employ “focus groups” consisting of people chosen deliberately to reflect the target market of the intended audience for the project. These groups sit and watch production test shots, giving feedback to questions set by the crew. It is also possible to ask specific questions relating to the presentation of factual information, should the project demand that level of scrutiny. Animated campaigns for advertising will also have to go through consecutive stages of approval, including target audience tests, detailed client scrutiny, and, in some cases, statutory regulatory bodies to ensure compliance with certain industry standards.

Animation students in a critique explaining their formative ideas at the Royal College of Art, London.

Conclusion

With a script written and the central ideas developed, considered, and tested, and any resulting problems corrected, the project is ready to move from the preproduction into the production phase, subject to developments concerning visuals and sound being agreed by the director. The project takes a step closer to becoming a reality, with final structural decisions made by managing members of the crew—usually the director and producer on larger productions—that will impact on the project work schedule. Revisions are made where necessary to help support the project, often in consultation with its commissioners.

In the next part of this book we will see how the project is developed by breaking down the specific elements of the production of an animated project, including creating artwork through different animation processes and techniques, and capturing these expressions through set design, camera moves, and lighting techniques. We will also introduce and establish ideas for applying and integrating sound design into the project. These specialist tasks require skill, knowledge, and awareness of other members of the crew, and the next chapters outline the often absorbing and intricate work that turns a project into a production.