This chapter explores the development of an animation project in the transition through the preproduction phase into production. As we have seen, the project concept has been introduced and scripted and a series of resulting ideas explored, researched, and developed. The material has been consolidated through discussion and visually presented by the preproduction team as an agreed rough draft of the final project. It has then been delivered through a pitch to the client. Now the project needs to take on a more detailed physical shape, putting those initial ideas into practice, finding out where there are likely to be production problems and attempting to resolve them. This development stage will take a good proportion of the overall project timeline to complete, since decisions made in this process are integral to its success.

In the development stage, the material collected during preproduction needs to be explained in a visually succinct way to the production team. For example, the overall scripted and previsualized story should suggest how the plot or idea unfolds for an audience, including how directed camera angles and movements will add increased drama, altering the narrative or conceptual pace of the content. With animation being employed widely in projects, the order of tasks in the production process may vary. As a general rule, a storyboard needs to be originated and developed first to help inform layout designs. Considered layouts need producing, testing, and developing to communicate the content with cinematic impact, acknowledging the ability of an animated product to squash or stretch the passage of time convincingly. Characters then need to be originated, developed, and tested to check they are credible for an audience to identify with and understand. These characters will be required to possess and exhibit characteristics capable of delivering the actions outlined in the script and storyboard through an appropriate production process, or combination of processes if multiple animation techniques are being employed.

Thoughtfully planning a storyboard can help formulate a framework for a production by laying out the key action points of the story, providing a coherent structure to commission voice talent, composing the score, and collecting sound effects.

Animation pipeline

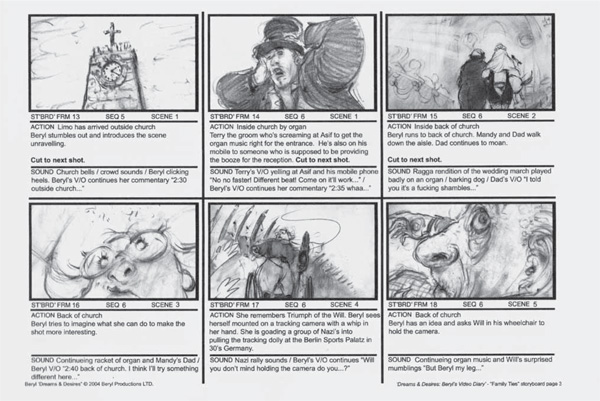

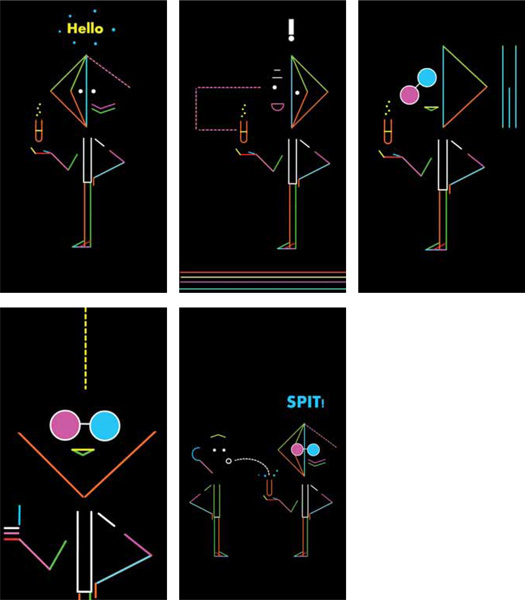

Storyboard: A storyboard is developed to illustrate the emerging narrative, setting the scene, introducing characters, establishing where dialogue fits with action, suggesting camera shots and angles, and determining sound effects. This is tested as an animatic, merging vision and sound to start to make sense of pacing and timing of the material for the audience. As the production develops, so does the quality of information held on the storyboard.

Development: Sets, scenes, and characters are visually developed in tandem with the collected research material as the crew work out how to animate the information contained in the storyboard. This involves detailed analysis of how the production is constructed (how to move items on set, how characters walk, talk, and interact, how lighting will be set and cameras will capture each frame) so that any production issues are resolved prior to filming. The production schedule is established and published for the crew.

Storyboarding became prominent as part of animation production as animated feature films became more popular, as studio animators needed to communicate their ideas efficiently through quick visual storytelling. © Disney

Storyboarding

A storyboard comprises a collection of numbered static visualized images that represent pivotal film frames. They illustrate the important points, known as “key stages,” of an animated script or story in chronological running order. These key stages are largely determined by the type of animated project being undertaken and the availability of such components as the script, the soundtrack, and any necessary dialogue. Some independent animators and studios create storyboards as a way of originating or informing a provisional script, while in other instances the storyboard is created in response to a written treatment. Regardless of how they are conceived, storyboards are an important shorthand visual aid in helping the crew understand the basic production information involved in animating the story.

Storyboarding was first employed on a major industrial scale by the Walt Disney Studios in the early 1930s, although there is evidence that the practice of drawing and posting images was pioneered at the studio some years before. Animator and historian John Canemaker suggests that “story sketches” were employed in the planning of Disney’s Steamboat Willie (1928) and Plane Crazy (1928), films that introduced the cartoon phenomenon of Mickey Mouse to the world. These sketches were pinned to the walls of the studio to help communicate story ideas to the team of animators, and were certainly in place in the production of the 1933 short The Three Little Pigs.

Storyboarding has successfully continued to traverse moving-image production in subsequent decades, being an important process in the development of big-budget live-action features, in documentary filmmaking and, most recently, in designing the order and navigation of animated websites and applications for personal mobile devices.

Storyboarding: from single to serial imagery

Typically a storyboard comprises visualized and noted information in individual boxed panels known as “frames.” These correspond to the proportions of the final production format, which depends on the selected broadcast format. Broadcast formats differ depending on the source of output, geographical region, and recognized broadcast standards of different countries or regions.

Storyboard frames are usually grouped in collections of 12, 24, or 36 boxes and may run over multiple boards to show the key frames from the beginning to the end of the production. Each panel is supported by some, or all, of the following information:

• a chronological scene and corresponding shot number

• a brief narrative description, or a collection of symbols such as arrows to illustrate how the camera will “move” in the scene

• a description of whether the shot will be created using long, medium, close-up, extreme close-up, or wide-angle camera positions

• additional information such as script inserts, director’s notes, and narrative ideas

• provisional passages of narration or dialogue to supplement the visual information

The process of constructing a storyboard has three basic phases. First, a rough thumbnail storyboard, produced in either black and white or limited color, is created by one or more animators to rapidly establish the important core actions that visually suggest how the events work as key frames of the story. Second, the agreed rough thumbnails are worked up into larger drawings that include more applied visual reference material and give more detailed information about possible camera moves. Third, a final version or presentation board is created with additional frames to fill in the gaps between key frames. This acts as a strong referential visual framework for the animatic or story reel and allows for temporary dialogue and a rough version of the soundtrack to be seen alongside, creating a rough draft of the project.

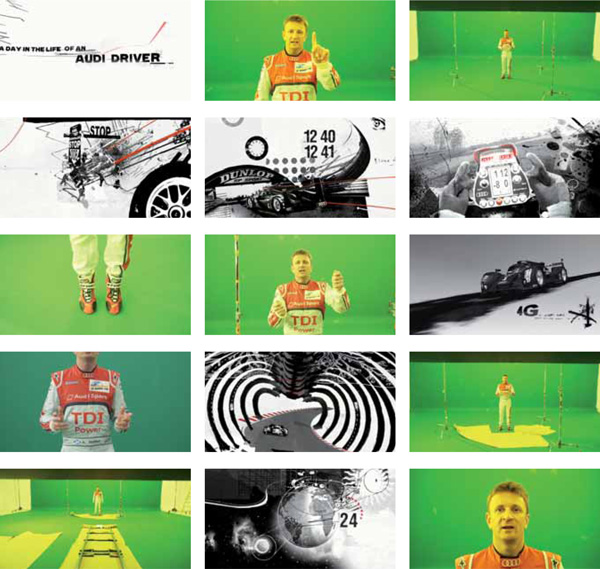

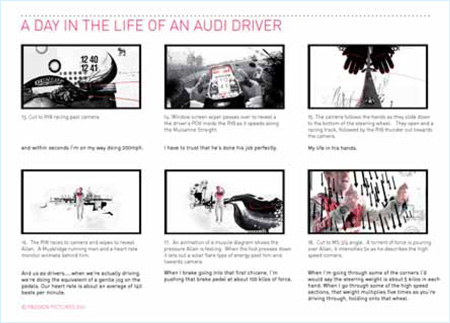

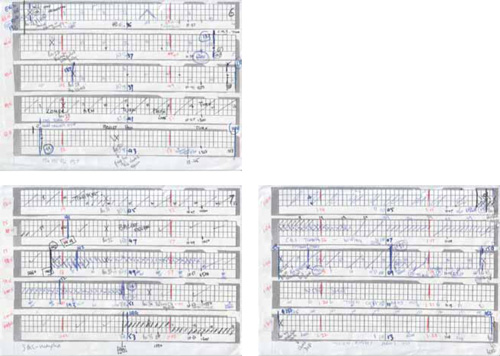

Presentation boards for Chris Curtis’s A Day in the Life of an Audi Driver advertisement provide essential information about synchronizing the timing of the visual story development, narration, and action occurring in frames.

The art of storyboarding

On a basic level, storyboarding is a technically cost-effective and readily available process employed to solve visual and aural problems ahead of starting to animate a project. More fundamentally, in inspired hands, storyboarding has also proved to be an arena where animators can visually express themselves through the act of interpretation—moving away from routine treatments to present something compelling, original, and inventive. Such artistic expression often gives animated work an immediate visual impact, although it will have taken the creator a significant period of time to develop his or her skill.

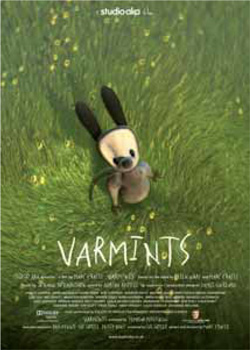

Some studios actively look for this personal style when hiring directors. Studio AKA’s Marc Craste is a good example of an in-demand director with an immediately recognizable visual style. Through short films such as Varmints (2008) and clever commercial work created for the British bank Lloyds TSB—designed to portray personal banking and finance in a more user-friendly light—his stylized characterization of figures and environments retain a whimsical, naïve quality and evoke emotional responses from the audience. However, individual flair is not a recent quality but something rather more symbolic of how animation has pervaded mass popular culture by giving us instantly recognizable icons.

Masters of their art

The visual characteristics of an animated production are rooted in a personal but collective aesthetic vision at the storyboard stage, where a script or series of visual ideas is brought to life. There are good historical examples that support this idea. The Walt Disney Studios’ development of storyboarding techniques in the early 1930s was, in some part, a response to the industrial type of delivery expected from Walt Disney. His vision for creating entertainment through storytelling extended to creating theme parks to embody his ideas about entertainment and mass popular culture more widely. In this era, storyboards not only were employed as a vital communication tool to inform animation teams working in the studio or to plan schedules for productions, but increasingly were used to test out Disney’s adventurous ideas for stories that potentially could go into production, without fear of committing large amounts of money for little return. Consequently, it would be easy to marginalize Disney’s storyboards as a largely soulless technical device without any artistic or design merits. But these animators were artists in their own right and inevitably were responsible for forging the studio’s signature style. This is especially recognized in films such as Pinocchio and Fantasia (1940). Similarities started to emerge in the visual signifying of characters in particular, with oversized facial features that could more immediately and expressively display gestures and poses.

The surreal and poetic animated short, Varmints (2008), demonstrates director Marc Craste’s ability to develop character-driven narratives that are engaging, thought-provoking, and memorable.

While conforming to a recognizable aesthetic, animators working on Fantasia (1940) were artists in their own right, including Oskar Fischinger, who expressed themselves by marrying the animated sequences to the music, helping to create the Disney aesthetic of that time. © Disney

Through the storyboards, animators could communicate how the character felt about a certain situation directly to the audience, using the graphically interpretive language of the cartoon. This form of telling a story sequentially enabled the artists to become acutely aware of the simplification possibilities of the medium of animation. They believed it was able to focus the audience on a particular message in a more succinct way than live-action film. This view was shared by public bodies, governments, and private companies, which commissioned studios to make everything from animated commercials for household goods through to war propaganda films, typified in the United Kingdom by the renowned work of the Halas & Batchelor studio.

The development of visual narrative in animation

The simplified visual language of the cartoon through sequential panels and strips is heavily connected to the art of framed storyboarding. Other cartoon conventions, including exaggerated figurative features and the placement of iconographic symbols, were increasingly used to illustrate actions and anticipate approaching movements. The Walt Disney Studios strike in 1941 came at a time when animated films had captured the American public imagination. The loss of production allowed other studios such as Fleischer and Warner Bros. to gain a priceless toehold through important figurehead cartoon characters such as the racy Betty Boop and the irrepressible Bugs Bunny respectively. These characters brought more sophisticated content to the animated feature, and with it demanded a visual styling that was more immediate and less artistically homogenized than the Disney offering.

The way was open for such animators as Chuck Jones and Tex Avery to take the cartoon art form to dizzy new heights, experimenting with movement and exploring the pace of narrative through the storyboards by varying the composition and placement of characters and scenes. They imbued their designs with deeper ideological references drawn from everyday life, including status in society, tolerance, and sexuality. They recognized that the storyboard was the place to test how characters could engage with the audience by drawing extreme close-up key frames and allowing the character to “know” that the audience was watching by depicting narrative asides to the camera. As a result, such films as Duck Amuck (1953) and What’s Opera, Doc? (1957) have rightly become regarded as masterpieces of their genre.

In subsequent decades, major art and cultural movements inevitably pervaded the art of storyboarding, an example being Disney’s Tron (1982), which pays visual homage to the American home video games revolution of the late 1970s. The present day sees many books published that specifically examine “the art of” a particular film through storyboards, early visualizations, and development toward finished imagery seen in the final release. Pertinent examples of these include Brad Bird’s The Incredibles (2004) and Henry Selick’s Coraline (2009).

The Halas & Batchelor studio was responsible for a significant number of propaganda films produced for the Second World War effort, including Dustbin Parade (1941).

Steven Lisberger’s Tron (1982) heralded the arrival of computer-generated imagery (CGI) in major studio productions, complete with the dynamic spatial qualities and aesthetic appreciation of the video game. © Disney

Creating a storyboard with a visual narrative

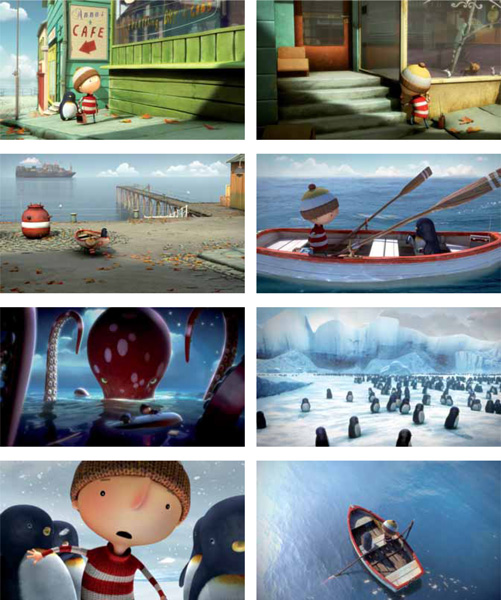

A coherent visual narrative style is necessary to bind ideas together into meaningful animated statements. This is also sometimes described as a “treatment.” The visual narrative or treatment will usually be informed by the director, who may have been selected because he or she has a deep conviction of how the project will look and feel stylistically to the audience. An example of this is Peter Docter’s treatment of Pixar’s Monsters, Inc. (2001). On other occasions, the visual narrative is governed by taking the stylistic lead from particular adapted works or from a treatment as directed by the brief. Good examples exist in the realm of children’s feature animation, including Dianne Jackson’s interpretation of the Raymond Briggs classic The Snowman (1982), Philip Hunt’s adaptation of the Oliver Jeffers story Lost and Found (2008), and Jakob Schuh and Max Lang’s rendition of Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler’s The Gruffalo (2009). The visual narrative can be immediately identified in every frame, resulting from a storyboard that has a consistent and informed filmic language for the crew to constantly refer to throughout the life of the production.

Each storyboard frame represents a “picture field,” that is, a depiction in two dimensions of a three-dimensional space. It is worth investing time in organizing the picture field to create an environment where the illusion of space and the considerations of reality can be juxtaposed into a believable visual narrative. Individual frames have the ability to communicate different emotions depending on the placement of characters and props in the picture field. Such placements create spatial relationships that can be harmonious, cohesive, reflective, or dramatic. These spatial relationships effectively act as controls for the level of drama that can be contained in the story, giving the director a greater choice of tools to determine the function and flow of the content.

Studio AKA director Philip Hunt skillfully retains Oliver Jeffers’s wistful lyricism in his adaptation of Lost and Found (2008), incorporating beautiful narration by Jim Broadbent and a memorable score by composer Max Richter.

This storyboard, from Joanna Quinn’s film Family Ties (2006), depicts the key frame of action taking place in the scene, together with annotations concerning forthcoming actions, camera moves, and sound direction.

The effectiveness of compositions can be controlled through the exploration of viewing and interpreting the visual material in the picture field. For example, lowering the horizon line creates a sense of impending drama, further intensified by a character’s being placed in the foreground above the natural eyeline of the viewer. Conversely, seeing shots from a raised position reduces this impact and makes the viewer seem more in control of a situation. These adjustments not only change the position of the camera, thereby giving the story different levels of impact at necessary points, but also have the added effect of making an audience concentrate on the story and become engrossed in the action taking place. This visual engagement is crucial in selling the idea to the audience, allowing them to feel empathy for the characters and providing them with a sense of purpose to see how the production will develop and ultimately conclude.

A style guide acts as a collective production bible for the animated project. Style guides are created to inform a coherent overall design strategy, to provide art-directed reference points for the crew, and also to include key information on the visual styling of characters, props, and environments. Practical design concerns, including scale, patterns, and color palettes of these key components, can be resolved by checking creative decisions against the style guide. Information contained in the guide has been informed by the research process, but manifests itself collectively through the storyboard, where creative decisions are taken about camera positions, settings, and necessary moves. Style guides are usually created by different members of the production crew and finalized by the director.

Much of the specific information gives crucial visual information that constantly needs to be referenced. For example, characters might be profiled in a series of drawn elevations from different sides to provide consistent and reliable reference points. Additionally, there may be model characters, perhaps sculpted as maquettes—effectively try-outs or practice models built to explore three-dimensional constructions. These can be created in various scales to provide three-dimensional reference for stop-motion characters.

Style guides will also include information about the way in which jointed or articulated versions of characters, known as “armatures,” are constructed. An armature is a framework that effectively provides the skeleton of the three-dimensional character with working engineered joints that can be posed to create different dramatic gestures. In this context, the possibilities and limitations of the armature must be demonstrated in the style guide to ensure consistency and clarity with the director’s vision for the production, but also to consider the limitations of the armature itself.

Style guides serve as a central collection and reference point, informing the art direction for a production.

Working on an exhibit for London’s Science Museum, Grant Orchard used molecular structures to inform his character development as part of an overall design strategy with Casson Mann’s exhibition design.

Layouts and scenes

The job of the layout artist is to design and construct environments for animated sequences to occur in, with each layout technically creating a “scene.” The layout artist translates information from the storyboard and works out the field space necessary to allow content to flow. This can include enabling characters to interact with other characters and props, and capturing any exaggerated movements the shot requires. Within the frame, the layout artist is responsible for technically enabling actions illustrated in the storyboard to happen, by creating a sense of time and place. He or she is also able to suggest a sense of atmosphere through the layout design in the use of negative space and spatial relationships between different visual elements. Significantly, the layout artist needs to have the ability to control the dynamics of the frame itself, but also to possess sufficient awareness for the imagined world of the production beyond the visualized frame. This allows sequential layouts to run seamlessly, creating a sense of natural cohesion and synergy between the scenes for the audience.

A fully jointed armature is a miniature engineering feat in its own right, often needing to be precision machined to withstand the rigors of continual manipulation on set, aptly demonstrated here by Barry Purves’s central character in Plume (2011).

In traditional two-dimensional (2D) cel animation, layouts provided a backdrop for action to happen against. Animators would position individual animation cels over painted layout designs. These animation cels were made of clear cellulose or acetate that had been drawn, inked, and cel-painted with a design. Photographing each cel independently would then create a frame. The illusion of movement occurred when the sequence of individually photographed frames was played back, typically at a rate of twenty-four frames per second, and the images appeared to move before the viewer’s eye. In traditional three-dimensional (3D) stop-motion animation, members of the production crew involved with layout face the additional hurdle of working in a modeled three-dimensional space. They need to design with consideration for both spatial awareness and the requirements of animators, who must be able to access the set easily without disturbing props or characters. They also need to consider carefully the use of materials in an environment prone to dust, heat, and changes in humidity.

Layout artists clearly need to have a sound knowledge of fundamental drawing skills, including an understanding of the principles of perspective. They need to understand how these principles marry with the cinematic concerns of staging, lighting, framing, and achieving suitably dramatic camera angles. This enables the dramatization of the narrative to be explored in action and allows the capabilities of the layout design in relation to the planned storyboard to be tested out.

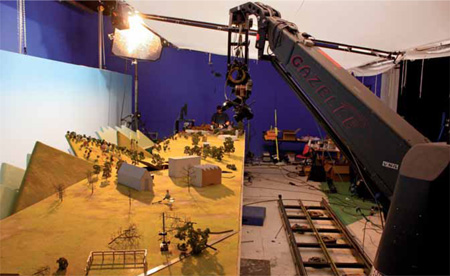

This behind-the-scenes image from director Suzie Templeton shows the level of detail required to construct sets with correctly scaled props that can stand up to the rigors of being continually manipulated by animators on set.

The translation of the storyboard into practical layouts means that both visual and narrative problems can be identified and resolved before progress can be made. Some technical problems can be foreseen in 3D stop-motion animation, for example, where certain shots are impossible to capture because the camera cannot physically be fixed into a particular position, or where the scale of certain props prevents desired movements from being engineered. In other instances, the layout artist’s quick-wittedness combined with an ability to change or consolidate a scene with minimum distraction is required, occasionally leading to some “happy accidents” that could not have been predicted by the storyboard. Wherever possible, planning technical resolutions to problems highlighted by visualizing the story helps to keep the project on track and on budget by predicting problems early, and there are some specific tools and techniques that can aid production.

Field guides

A “field guide” is used widely in two-dimensional animation to help layout artists imagine and construct the picture field while working on the layout. It has the immediate effect of visualizing what the camera will crop. For example, if the director wants to move from an establishing shot to a close-up, holding the field guide between the eye and the layout enables the layout artist to see instantly what that camera shot will look like for the audience. The field guide typically consists of a clear sheet in a lightweight frame, marked with a faint static grid of rectangles. These act as an immovable framework. Bigger rectangular windows are placed or marked on the grid corresponding to the aspect ratio the production is going to be shot at.

The design and layout of any set must necessarily include technical considerations, including the placement of lights and cameras to permit the shot selection deemed necessary by the director.

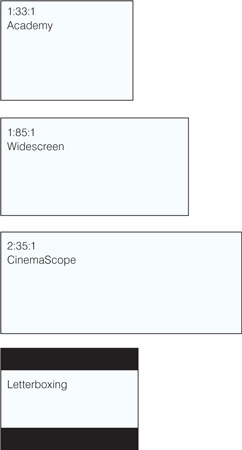

Different aspect ratios are required for formatting to different viewing platforms.

Field guides conform to common production aspect ratios used by different broadcasting platforms:

• Academy ratio is 1:33:1

• Widescreen ratio is 1:85:1

• CinemaScope ratio is 2:35:1

• Letterboxing involves placing a black slip above and below the frame

Layers

Creating artwork in layers allows layout artists flexibility with their designs. In traditional cel animation, clear acetate sheets are applied over each other to ensure movement flexibility of key components, while other elements of the design can remain static, saving production time and unnecessary expense. The advent and application of digital media accelerates these principles, and has the added benefit that layers are virtual rather than physical. This is a distinct advantage for the layout artist, where the problem of layering traditional physical cels would eventually lead to parts of the overall artwork appearing to fade or lose focus. Every layer can be controlled individually so that it is seen at the same intensity if necessary. Technical flexibility aside, the layout artist still needs to factor in how many layers are required for the scene to be conclusive and readable, rather than overly complex and confusing.

Cinematic thinking

The ability to think cinematically is a principal requirement for anyone interested in making an animated project. It is a key skill that studios and partners look for when seeking potential support for a production. Cinematic thinking encompasses the conceptual and physical process of determining and visualizing camera angles and choosing shot selections. These decisions to represent the content of the project can shape the production dramatically. They allow rhythmic changes of narrative pace to reflect action in the plot, or to create visual pauses while the audience absorb and understand information being imparted. The ability to think cinematically gives productions a unique identity of interpretation, and also ensures that particular elements can be framed so that they remain as memorable markers in the audience’s mind.

Essentially, the camera acts as the eye on the production and the captured information is described as a “shot.” This imparts ordered information on a basic level, but can also stir emotional responses from the audience if used imaginatively. The camera can be employed in fixed or variable positions and further cameras can be added to create different shot options—of the same frame if required—that will allow directorial choices in the editing phase. There are several possible types of basic camera move that give creative freedom for the director to mix moves to achieve a desired shot:

Barry Purves’s Tchaikovsky (2011) is a poignant and touching account of the composer, meticulously captured using a variety of shots by Justin Noe and Joe Clarke.

• panning—the camera creates level horizontal movement from side to side

• tilting—the camera achieves level vertical movement up and down

• dollying—allows the camera to move into or out of a scene

• tracking—allows the camera to run with the action by the aid of a moving position as it travels through a scene

• craning—enables the camera to be attached to a device that can swing, dip, and travel through three-dimensional space, effectively anticipating, following, or reacting to action in a scene

Variable positions can be achieved by removing the camera from its fixed position and hand-holding it, or by attaching it to a device where it can capture information from unexpected sources, such as a balloon. Such camera techniques are often employed in documentary and independent animation, where they are often used to convey the effect that the camera was hidden in a location that was not visible to the subject being filmed.

Establishing shot—used to introduce a scene and explain the context to the audience by acknowledging external factors. For example, we might see the scene of a street, but recognize from other information in the shot that the street is in a seaside town.

Medium shot—enables a character or object to be seen against the context of his/her/its immediate location, for instance a security guard standing outside a neighborhood bank.

Close-up shot—directs the viewer’s gaze to a particular aspect of the shot, for example, a soldier squinting down the barrel of a rifle.

Extreme close-up shot—examines in detail a focal point, for example, using the illustration above, the soldier’s eye taking up the whole frame.

Bird’s eye—focuses on the subject from an overhead position and gives a sense of place and purpose to a scene from an unexpected position, which the subject may not be aware of, for example, the enemy moving into position on a battlefield.

Dutch angle—an unusual but dramatic shot, where the camera is placed at an oblique angle, making the horizon line dip or lift from one corner of the frame to the other, conveying tension.

Follow shot—as the description suggests, this shot pursues a character or subject through a scene.

Forced perspective—the camera is used to capture optical illusions of subjects in a scene by placing them together but, for example, exaggerating or minimalizing scale to give them unusual values and properties.

Using a variety of cameras in different positions allows variable shots and options for a director that are crucial when scrutinizing a scene for maximum impact, as demonstrated here in Madame Tutli-Putli (2007).

Freeze-frame—the camera captures a precise moment in time.

High-angle shot—the camera is fixed above the eyeline of the character, allowing the audience to look down and suggesting a superiority to or power over the subject.

Low-angle shot—the camera is fixed below the eyeline of the character, allowing the audience to look up and suggesting an inferiority to or fear of the subject.

Point-of-view shot—the camera intimately sees what the audience perceive the character or subject sees directly, although this may also include the character or subject in the frame if the camera is looking over the character’s shoulder, for example.

Reaction shot—the camera records the reaction to a scene or event being showcased. For example, if a soldier is wounded, the reaction shot reflects the immediate reaction of his fellow soldiers.

Sequence shot—also known by the French term plan-séquence, this shot allows events happening in the mid-ground and background to take precedence over what might be happening in the focal point of the scene among the main characters.

Zoom—an extremely versatile and popular action: keeping the camera still but adjusting the lens takes the subject closer to or farther away from the audience.

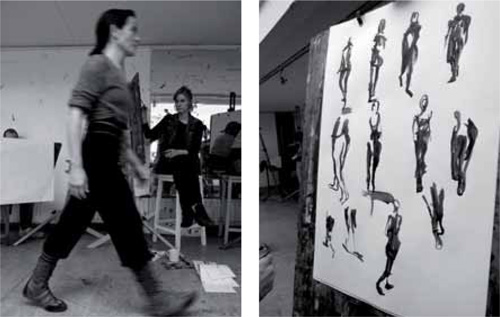

Joanna Quinn’s human studies reveal an animator who places great emphasis on her ability to observe, but also to interpret those recordings systematically to explore the developing character’s nuances more accurately.

With careful direction and selection of shots, and the support of equally considered and applied sound design, the audience should not notice key technical production processes, concentrating instead on being transported into a make-believe world through the development of the content. A variety of carefully considered shots is essential to ensure that content transfers smoothly from camera to screen, aiding audience appreciation and understanding of the production.

Development drawings

The importance of drawing to animation development has been highlighted previously as a skill that requires aptitude, practice, and time to master. As the project develops, drawing takes on a more considered and detailed role.

Historically, the drawn animated image was central to determining and defining animation’s legitimacy as a recognizable art form. In the contemporary era, some of the immediate resonance of drawing may have been partially hidden by advancing technical production processes. However, much of the underlying success of productions is still owed to an invested sense of drawn activity and language. Drawing both encourages and rewards observation and imagination—two of the basic ingredients defined and celebrated by animation. It is a vastly adaptable and expressive skill, easily able to encapsulate and merge exaggerated movement and description.

Imagination and observation

A basic element that animators need to have in abundance, and expect to develop, is imagination. The creative flair, passion, and drive of a given project are drawn from an individual’s capacity to bring vision, excitement, and appetite for the project to the wider team and to encourage that vision and belief among others. Whether we look to innovative pioneers such as Peter Lord, visionary directors like Tim Burton, or the wit and charm of animators such as Joanna Quinn, imagination fueled by the desire to observe and record the wider world is a skill that is greatly applauded by fellow creators and audiences alike.

In practical terms, observation is something often marginalized and overlooked by students. Looking is something we are routinely accustomed to doing, our brains continually taking on board information and processing responses to stimuli set out before us. Seeing, in the context of the arts more broadly and animation in particular, involves far more focused and concentrated study. Here, seeing is akin to decoding and understanding subjects, compartmentalizing captured information to make sense of the bigger picture being presented. In animation, such activity can be taken to extreme measures through the artificially constructed nature of the form. Creators experiment liberally with visual, aural, and structural components of a production to illustrate observations in varying degrees of detail and complexity. More specifically, the structural elements of drawing, such as composition, placement, and emphasis, can have a profound effect on the delivery of content if imaginatively employed.

Students undertaking a life-drawing class at the Royal College of Art, London, learn to see “through” the figure to the transformative possibilities of the human form as a storytelling device.

Understanding the visual dynamics of the frame allows the animator to control the order that specific pictorial elements are seen by the audience, creating opportunities to emphasize or hide clues through careful placement.

Fundamental aspects of composition, placement, and emphasis

While the storyboard provides an overview of the production, it is widely understood that development inevitably leads to changes in how particular aspects of the project are interpreted. The ability to alter the composition of frames is necessary to ensure that the information and the central theme of the content are organized and edited, ensuring clear explanation. Within the frame itself, the placement of visual elements, and the resulting relationship they have with one another, allows the audience to understand and interpret information based on the emphasis given compositionally to those subjects.

Animators use design elements such as line, shape, color, texture, form, tone, and space to explore composition. Each of these elements can be employed singly or collectively to act as visual signposts that will attract the viewer’s eye and direct it toward vital information. In determining composition, it is important to understand who or what the focus, or center of interest, of the frame will be. Having established this, other clues are provided in the composition to establish a unity of information and a harmonious, balanced frame. Organizing the composition effectively involves making critical decisions about the shape and proportion of key elements and how they balance themselves against each other. This might involve using geometric or natural forms to explore such aspects as perspective, negative space, color contrasts, and lighting. Controlling these aspects alters the visual rhythm or beat of a sequence of frames making up a scene, effectively controlling the pace of how visual clues are illustrated for the viewer.

Dividing up the frame compositionally can have a profound effect on how images are understood. For example, the “rule of thirds” uses the idea that the frame is divided by three vertical and horizontal lines, and that elements are placed on or close to where these imaginary lines intersect to create a harmonious and balanced composition. A similarly pleasing compositional aesthetic device is the triangle, its implied shape within an image acting as the foundation for a face, for example, where the corners of the mouth line up with the corners of the triangle, while the point lies between the eyes. Frames that have an odd number of elements appear more informal owing to their lack of symmetry than those made of an even number of components.

To create emphasis in a frame, the animator must position elements in a visual order that will be read correctly by the audience. For example, the introduction of a character usually involves using a close-up composition or shot in the first few frames to allow the audience a chance to identify certain characteristics or personality traits. Emphasizing key elements involves editing. To be a good editor, an animator must be able to identify which are the key components of a frame and to see these in the context of supporting narration, dialogue, or soundtrack. It is important to consider all aspects of the production, as having multiple visual and aural effects can clash, confusing the audience. At all times, it is important to use a certain economy of scale when considering visual elements, or vital aspects of a scene may be lost under superfluous detail. This requires careful planning and animators use a number of tools, processes, and techniques—dope sheets, key movements, key frames, line tests, the story reel—to help in this regard.

Dope sheets

A “dope sheet,” or exposure sheet, is effectively a blueprint plan of the production. It shows the production crew at a glance how elements of visual and aural material are to be pieced together in the production with correct timings. The dope sheet is used to break down individual technical elements into units of information, such as annotating which layers of artwork are being used in a particular shot, the camera moves required, the part of the script being animated, a guide to the supporting soundtrack, and any additional sound effects needed. This information is held on the spreadsheet, clearly indicating how many frames each of the components explained above will last, and projecting what is about to follow in the production.

An exposure or “dope sheet” allows visual and aural components of the production to be broken down in timed segments to maintain consistency of flow.

One of Koji Yamamura’s key frames for the animated short, Muybridge’s Strings (2011), produced for the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), is ready for scanning.

Key movements

Animation occurs through the movement of objects between frames. The frequency with which objects move can alter, but the consistency of movement of the object itself varies depending on its function or purpose. In a movement, there are points that explain the magnitude and frequency of the action and these are known as “key movements.” For example, imagine that a ball bounces in front of you. The two key movements of that particular bouncing action are the impact as the ball hits the ground and the highest point of the arc of the bounce, signifying that the ball is bouncing from one point to another.

Key frames

In traditional animation, “key frames” are identified as being the start and end points of a sequence of smooth transitional animated movement. These key frames represent pivotal points where the greatest degree of the move occurs, with the remaining frames in the sequence known as “in-betweens.” Animators establish and create key frames, and while traditionally animators known as “in-betweeners” would develop, “clean up,” and execute the adjoining frames, today this process is for the most part digitally constructed using software such as ActionScript.

With other digital platforms, such as Adobe Flash, the animator creates key frames but relies on the process of software to fill in the spaces smoothly through a technique known as “tweening,” whereby images are seamlessly interpolated into the sequence. The versatility of tweening software enables changes to a movement to be easily accommodated. The predictability of such a mechanical technique can be overcome by essentially “keyframing” each and every frame, enabling the creator to digitally manipulate and have complete control over the whole creative process.

Line tests

In traditional cel animation, a “line test” (or “pencil test” as it is sometimes known) can quickly and efficiently enable an animator to flip consecutive drawings by hand to see incremental movements created by a sequence of drawings. Drawings are created on separate sheets with a fixed point of registration illustrating a piece of action from a start to an end point. The drawings are then held tightly and flipped in the chronological order they have been created in, producing a linear sequence that moves between a beginning and ending frame of action. It is also possible to scan or photograph these individual drawings and play them back on screen if necessary. The process allows animators to ascertain if some drawn movements between one frame and the next are too pronounced and movement appears to jar or jolt as a result. Many programs now offer this facility for animators working in a digital environment.

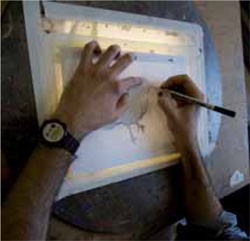

Using a registration or peg-bar, frames are drawn consecutively here on a light box before being scanned and played back in the corresponding order to create a line test to check animated movement through the frames.

An excellent example of an early animatic, with elements of live-action footage and illustrated stills bound together by a recorded script read through by racing driver Allan McNish.

The animatic or story reel

An “animatic” or “story reel” is created when individual frames from the storyboard are recorded and played back sequentially with sound. It is created to show the production crew what the finished project could look like. Sound can be a rough recorded voice-over taken from a first reading by an actor, clips of recorded dialogue or suggestions of how an instrumental or vocal soundtrack might contextualize the imagery. Projects can have any number of animatic sequences and it is quite common for animated content to be routinely tested in this way as it allows changes to be implemented without major cost revisions.

The legendary Walt Disney Studios animator, Frank Thomas, was one of Walt Disney’s early recruits. One of the affectionately nicknamed “Nine Old Men,” Thomas inspired generations to work as animators. © Disney

Character design

Characters play a crucial role in animated productions. They must be designed for various uses, from acting as key defining tools for explaining the developing plot, through to establishing a recognizable presence audiences can identify with and attach an emotional response to. Characters have even adopted the role of brand ambassador for the movie, television series, or product being advertised, an example being Homer Simpson. A character’s versatility of function is a core requirement of his or her design and needs important consideration when the character is being created. Time invested in this stage of the process often reaps rewards later in production. It is a common occurrence to check early development of character development using a simple line test (see page 92) or a walk cycle (see page 99) to better understand the form, function, and versatility of the character.

The bones of character design

Character design goes beyond the simple outward visual appearance of a character and instead considers the potential overall embodiment and flexibility of the form. This includes rudimentary inner facets such as stature, posture and gesture, movement, and expression. Historically, a technique known as “rubber hose” movement was used to animate characters, so called because it tended to elasticize a character’s movement and was considered more efficient. The approach was developed by the Walt Disney Studios in the 1930s as preparations for industrialized animation production on a far greater scale gathered momentum.

Walt Disney’s decision to hire artists had a massive influence on the form, and their influence served to bring artistic principles of anatomy and movement to mass industrial practice. These artists looked adventurously at the way animation techniques could potentially illustrate the diversity and complexity of articulation of the human form. Such approaches led to examples of “full animation” in feature films. Here, every frame was hand-drawn, ensuring the character’s movement could be completely manipulated, resulting in visual fluidity and greater options to explore a character in motion, classically illustrated by The Three Little Pigs (1933).

By contrast, other studios such as UPA used a technique known as “limited animation.” This relied on sequences of drawn animated material being used in cycles or holds as a way of economizing, and depended instead on supporting techniques, such as voice-over or a greater variety of camera shots, to complete the production. The technique has the advantage of being quicker, more efficient, and cheaper than full animation, and is used today in many animated television series, Japanese anime such as Pokémon, and animation for the Internet. Far from being “limited,” the true test for limited animation is that it forces the animator to be inventive about where and how to show movement.

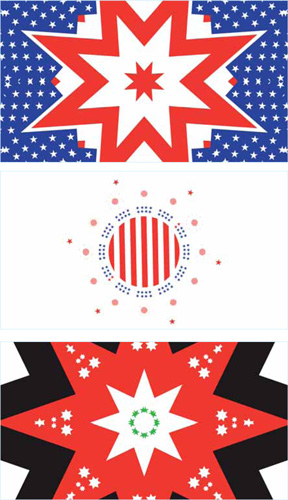

Experimental animator Max Hattler’s film Collision (2005) is a good example of “limited animation,” using repetitious, geometric, symbol-laden shapes in quick succession to play on deeper political and ideological differences between contrasting nationalities and states.

In recent years, historians of animation have made connections between the art of animation and the major art movements, serving to highlight parallel concerns and centralizing the view that animation was very much contextualized by developments in the wider world. More recently, animation has begun to have a profound impact on the definition of the arts more generally as it pervades feature films such as James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), video games such as Gran Turismo and Call of Duty (both 2010), and even the opening ceremony performance at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, where animated diving whales were projected on the center field of the stadium. If Chuck Jones and Tex Avery championed “art” through their now infamous characters, such as Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, the mantle has certainly been picked up and carried in the contemporary era by the likes of Nick Park, Philip Hunt, and Matt Groening.

Keen to evoke a sense of national pride and passion, the Canadian organizers of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver chose to commission special animated effects to illustrate the cultural and spiritual identity of the host nation to the watching world.

Characters need to be easily recognizable, able to be identified through their appearance, voice, abilities, and actions, and also capable of carrying and enacting the story to the viewer clearly and functionally. Their increasing visual prominence and recognition as forms that exist beyond the world of an animated production has inspired leading Hollywood actors, including Tom Hanks, Tim Allen, and Dakota Fanning, to voice household names—in these examples, Woody, Buzz Lightyear, and Coraline respectively.

The role and function of character

A character is not a solitary object that exists in isolation, but rather a vital component that works in tandem with other aspects to bring life, action, and explanation to a production. In this context, his or her role is to provide the audience with a sense of anticipation. The director’s inclusion of a character signals that he or she is in some way important to the development of the plot and has the ability to deliver information, whether this is factual, entertaining, or informative.

The animator’s ability to understand movement, and its visual depiction, is key when considering the design of any character. The audience need to believe the capability of a character to move, communicate, act, and respond to the world around him. Animators often look to the performing arts—typified by dance, mime, theater, and street arts—where movement is often exaggerated and staged. In this way an action can be amplified and overstated, emphasizing a particular movement more efficiently and directly than if it was naturally conducted.

This is an important facet of animation, because these heightened actions enable conceptual and physical conventions to be removed from presented characters. This allows the audience to begin to invest in and understand the characters for what they are being presented as, rather than what they might be thought to be. An example is a character such as Astro Boy who, as his name suggests, is in some way linked to outer space but whose characteristics need to be understood and approved by the audience in order to validate his supernatural ability. Permitting these actions to occur requires an understanding of key technical skills—timing, lip-synching, and movement—combined with a confidence in making the unbelievable seemingly come alive through the suspension of disbelief. These skills are largely invisible as the character is not seen in isolation, but without a mastery of such techniques characters can appear unconvincing.

The Brothers Quay film, Street of Crocodiles (1986), is an excellent example of the suspension of disbelief principle in animation, where the tension between stasis and flux is palpable.

Timing

In all forms of animation production, the ability to understand and control time is a central issue. In character design, an understanding of time allows the audience to engage with and have empathy for the character, mapping their movement as it is synchronized against the other production elements of voice-over, dialogue, and supporting sound effects. Mastering the techniques of timing allows the sense of time to be constructed, manipulated, and exaggerated through controlled movement.

In principle, a character functions on an invisible axis or line of movement. Horizontal movements are conducted along a simple “x” axis, while vertical movements take place on the “y” axis. In three-dimensional animation, where the properties of the character in space can be explored, depth is represented by the “z” axis and can often produce some startling and unexpected results. Similar possibilities occur in two-dimensional animation, where an understanding of the rules and applications of perspective can produce scenes exploiting optical illusions with characters, especially where exaggerated scale is used between the depiction of character traits and environments, as illustrated by Gerald Scarfe’s drawings for the Pink Floyd film The Wall (1982).

Once a character is given license to move, it needs to display these motion qualities openly to the viewer, mimicking and exaggerating our own understanding of the timing of movements. For example, characters can be imbued with the sense of “anticipation” that a movement is going to occur. Anticipation signals that a movement is going to happen and is directly linked to previous and future movements. At the end of the movement, an action known as “follow-through” occurs, where the body is allowed to come to a natural rest rather than freezing still. Anticipation and follow-through can be considered forms of animated punctuation and their use can make movement seem more natural and less artificial.

These illustrations ably demonstrate the challenge of visually interpreting the complexities of human movement, including anticipation, follow-through, and holds.

Equally, absorbing and promoting this understanding of timing allows instances such as pauses, which help the audience to identify characters and signify moments where action can take a different course, or plot direction can change. Such pauses may not be immediately noticeable directly to an audience, because they are masked by other production effects, but they serve to create visually grammatical “holds” where the audience can focus on an upcoming event or regroup after an intense period of action. It may require many years of practice to understand and develop this skill, but its application can undoubtedly make a substantial difference to a production.

Other effects such as gravity and physical possibilities and limitations also present timing possibilities and obstacles. Even if characters are not firmly rooted stylistically in a realistic approach, the audience is conditioned to expect that certain events will “naturally” occur. Changing such elements often leads to synthetic-looking results. Examples include when an object appears to float because it lacks an expected mass signified by its scale and depiction; or when the impact of a collision fails to refer to the traveling mass of a colliding object, such as a train hitting a station platform and the resulting devastation being proportionally smaller than anticipated. Adopting a “slow in” and “slow out” approach demonstrates that the animator understands that movements are not continuous, but have natural rhythmical interludes that accelerate and decelerate to reflect the nature of a complete action.

Lip-synching

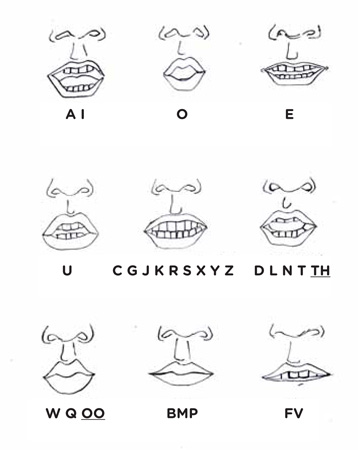

A way of convincing the audience that a character has come to life, expressing the ability to breathe and talk, is through the technique of lip-synching. This is a complex and tricky technique, conducted on an almost frame-by-frame basis, and requires continual intervention by the animator not only to render the mouth in the right position for every frame, but also to anticipate end movements as naturally as possible. For English-speaking characters, there are nine basic types of mouth shape (see drawing opposite) to signify and imply recognizable speech and suggestion. For example, many people do not close their mouth immediately after speaking a word. It is this sense of naturalistic behavior that the animator is looking to impose on his or her character. Equally, the sense of responding to a question through the anticipation of sound, movement, and concurrent breathing is hard to reproduce faithfully. Slight movements to the mouth shape signify a change between vowel and consonant sounds within a word, and it is important to see these as linked shaped sounds, rather than concentrating on the noise of the individual letter itself.

The nine basic mouth shapes employed by animators to imply speech. Groups of letters create specific sounds that must be linked together frame-by-frame to achieve consistency and aid believability.

Clearly, any form of lip-synching is closely linked to secondary actions such as facial expressions. Economizing on lip-synching to allow other features, such as eyebrows and eyes, to convincingly amplify emotions should be considered. A good example is Nick Park’s animal creations from the animated short series Creature Comforts produced by Aardman Animations. These films source voice recordings of the general public talking about a given topic, and are interpreted as different animals, who mimic human gestures and behavior. Created in stop motion, the models are made of Plasticine modeling clay, which can be manipulated and sculpted to form different expressions to support economical mouth movements. While lip-synching in production means that the animator concentrates on a particular aspect of the face, it is worth remembering that the audience will be able to see the character as a whole and that other facial features, limb movements, and the overall posture of the character can also support the story.

Originally commissioned by British Gas as commercials, these short films by British studio Aardman Animations became so popular that the Creature Comforts series was created. Their acute observation of mundane everyday happenings, adapted into extraordinary situations through stop-motion animation, is their key to success.

The walk cycle

Producing a “walk cycle” allows the animator to better understand the possibilities and limitations of a character’s movement. Still linear drawings of a figure in isolated walking movements are sequentially created, scanned, and played back, indicating how potential movements might occur. While it is predominantly centered on the articulation of movements of crossing and stretching in the lower body and legs, a walk cycle fundamentally introduces the principles of related movement to the body as a whole, as it is connected and therefore creates secondary movements.

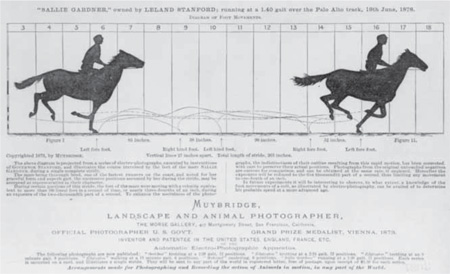

Eadweard Muybridge’s revolutionary photographs of animal locomotion revealed to a disbelieving public that all four horse’s hooves leave the ground when galloping.

Since the work of early motion-capture pioneers such as Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), whose The Horse in Motion successfully proved to doubters through the use of stop-frame photography that a horse lifts all four feet in the air when it gallops, animators have continually strived to prove that characters they have designed have the ability to freely anticipate and respond to movement. In short, they respond to the laws of physics that govern them, whether real or imagined.

The walk cycle confirms vital and necessary connections that can inform aspects of the character’s physical appearance, having a profound effect on an audience’s understanding of the character. For example, producing a walk cycle allows exploration of different facets of movement, from shuffling and ambling through to leaping and bounding. This will include the “rise” and “fall” of the body as it naturally and rhythmically contends with deliberate directional movements.

Suspension of disbelief

The “suspension of disbelief” is achieved when an animated sequence succeeds in appearing to make an impossible act happen, like a character lifting up a car over his head. This is achieved using a balance of accepted and reassuring elements on screen and allowing the impossible character or act to operate within the confines of the scene. Animators need to balance the audience’s established views and beliefs, but introduce and embed objects or situations in a position where the impossible can, seemingly, become not only possible but also believable.

Given that animation is a form based on artifice and illusion, it offers extraordinarily broad and free license to indulge in creating characters that challenge assumptions and suggest new and exciting directions. It is nearly impossible to create something entirely original since animation, like all disciplines, borrows ideas, practices, and purposes from a multitude of quarters. It is, however, right to suggest that some approaches, whether conceptual, practical, or technical, will be new to animation.

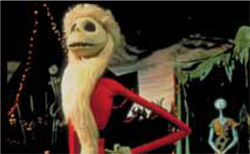

Jack Skellington from Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) displays many of the hallmarks of Tim Burton’s richly imaginative view of the world. © Touchstone Pictures

Character as protagonist

Animation has been likened to the art of metaphor, reflecting perceptions of the culture surrounding us and projecting them into imaginary captured worlds. Central to this idea is that the character becomes symbolic as a figurehead or protagonist, helping to carry the plot, expressing the director’s ideas, and authenticating the content of the production at large. This might include the moral, ethical, or political standpoints the director wishes to portray and with which he or she wants the audience to empathize. Protagonists can be heroic or villainous, and there may be more than one protagonist, especially if the story contains subplots.

Many examples exist in animation, from feature films to animated commercials, where the character often becomes the “hook” that the viewer responds to. A good example is Jack Skellington from The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993).

Developing characteristics

Your character is a shell until defined by its characteristics. These properties give your character its identity, personality, and purpose. Characteristics establish a set of beliefs, justifications, and contradictions. Working through these questions as you think about your character will help shape your design process, allowing you to test your ideas before developing the character so far that changes become difficult to accommodate later.

• What is the target market for the production?

• Who does your character need to appeal to and why?

• What do they need to achieve?

• What is their history?

• Where have they come from and what have they previously experienced?

• What is their perception of themselves?

• What are other characters’ perceptions of them?

• What are their capabilities in relation to communication and movement?

While countless examples of heroes and villains exist in animation, the Warner Bros. characters have a enduring appeal, typified here by Wile E. Coyote.

In order to believe in a character, the audience must be drawn into believing the overall look and feel of the wider production. It is absolutely vital not to look at the idea of developing characteristics in isolation. Animation is the sum of all of its parts and any element that jars will make the audience suspicious of the production overall. It is important that the context of the assumed environment beyond the screen is considered in order to ground the character. For example, when we see a character in a production, we naturally assume that he or she (or it) will have come from somewhere, will have had a previous life or experience, and will effectively be bringing these experiences to the screen. He or she will belong to a direct (seen) or indirect (implied) family tree and a wider world context and will have been shaped by conditions that may still be prevalent in the scenes and locations of the production as it unfolds.

Heroes and villains

Successful characteristics can instill a belief system in the audience that can identify characters as being good or bad. In animation, such feelings toward a character can be enabled through single or combined visual, aural, narrative, and ideological constructions of the form, capable of taking extreme directions and giving rise to the idea of the creation and expression of the hero and villain. In animation, as in comic books, the functions of heroes and villains vary according to the project being produced, but need to be considered in relation to one another—the one often requires the other to illustrate just how super or devious they really are. Animation history is littered with famous heroes and villains, especially in cartoons—for example, Tom and Jerry, and Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner—their extreme characteristics both embodied and projected by the nature of animation as a form.

The introduction of heroes and villains gives an audience a chance to intensively question, understand, and potentially align themselves individually with characters, giving rise to the idea that heroes and villains are actually animated “projections of self.” They embody our wants and desires, our fears, hopes, and aspirations. Like cinema, animation has the ability to propel heroes to the status of superhero by giving them extraordinary and unexpected powers beyond the standard comprehension of their supporting cast, location, or apparent ability. In an animated context, these additional virtues can be heavily exaggerated to suggest power and prominence, but they should also be treated carefully to ensure that characters retain some degree of vulnerability.

A point of view about the character might be introduced by the character’s appearance, personality, actions, or reactions to other characters or plot events. Development of characteristics might mean that the audience see these traits from the outset, as a result of action as the plot unfolds, or even at the conclusion of the production when they reflect back on what has been witnessed.

Objects or characters can change through “metamorphosis” into something completely different. In Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (2010), the mysterious character of the Cheshire Cat freely morphs from a cat into a swirl of smoke, playing with the senses of illusion and reality. © Disney

Metamorphosis

Movement is central to animation, but is not confined to shifting objects or characters from one point to another. More fundamentally, objects or characters can change through a process called “metamorphosis” into something completely different. This idea is crucial to animation as a form and represents myriad possibilities for the animator. It manifests itself regardless of the kind of process of animation employed and offers a wealth of options for the animator looking to move from one scene to another, or to shift the audience’s perceptions of a character. A good example occurs in Disney’s Alice in Wonderland (2010), directed by Tim Burton, where the character of the Cheshire Cat morphs from a cat into a swirl of smoke. Anthropomorphism is used widely in character design and is the imposition of human traits on animals, objects, and environments.

Narrative construction

All animated projects that encompass characters, regardless of their genre, need a structure to operate effectively. Here are some examples:

Compilation—various creators produce animated responses to a set theme or topic.

Cyclical—a story runs full circle back to its original starting point.

Effect—animation is used to provide extra dynamism to a situation, such as a rollover or a special effect.

Episodic—most commonly seen in television series where a wider story is told in separate components.

Gag—many jokes are visually told in quick succession that would be impossible to achieve in the same timescale through live action.

Linear—might typically consist of an introduction, a situation or drama, and a resolution.

Multi-linear—several stories are told simultaneously using a mixture of techniques, including edits or splitting the screen into different sections.

Non-linear—a story has inbuilt permissions to change each time it is seen, and is commonly used in games design where gamers can decide to go different ways.

Thematic—a story that does not move round or along, but instead invites viewers to investigate what is there in front of them.

Visual preproduction is complete only when the storyboards are signed off by the director, the layouts created, and the characters designed. The project now awaits approval from the commissioners and clients to move into full production. At this point, all aspects of the production should have been checked against the schedule and the budget. It is imperative that any issues concerning the projected schedule are brought to the attention of the director so that decisions can be made to help maintain workflow continuity, as many more crew members are now going to become involved in the animation pipeline.

In the next chapter, we will examine the importance of sound, and look at the role it plays in animation and how it is constructed and used to emphasize actions and movement in a production. We will investigate what considerations need to be given in the preproduction phase to ensure the form can be planned, recorded, and utilized to the full.