Conclusion: Climate and Culture

C.1. Climate “shocks” and resilience dynamics

Work on climate change is confronted with the general problem of the possible relationships between human cultures and climatic variations. For a very long time, the unstable climate was oriented towards the cold, and this formed the context from which the first human cultures emerged. Humans were then very few in number and socialized in small groups of hunter-gatherers. After a great climatic transformation, where the speed of rising water was the fastest around 14 ka (14,000 years before the present), a warm period settled in, profoundly modifying human cultures, with aspects of great political instability and a paroxysmal rise in social violence. Pierre Clastres [CLA 74] concluded that it was impossible for a pacifying public law to emerge in the many conflicts between the Amerindians of the North American plains. The sacrificial slaughtering of children to reconcile the El Ninõ climatic phenomenon on the side of pre-Columbian Andean and the Rocky Mountain civilizations leaves no doubt about the links between climatic instability and human cultures, but questions the political and religious transformations that may have brought them about.

This question of climate and culture suffers from the obsolescence of theoretical approaches. The political or medical climate theories represent a very great tradition starting from Hippocrates to Montesquieu, through Aristotle and Christopher Columbus. They were abandoned in the 19th Century with priority given to sociological explanations. Only the conception of static lifestyles in the tradition of human geography has survived [FEB 22]. Concerns about climate change focused initially on reducing carbon emissions, without addressing the question of how societies can adapt. It is only recently that the issue of “climate and culture” has re-emerged on the global research agenda [EUZ 17].

C.1.1. Static lifestyles

While questions are now being asked about the adaptive capacities of human cultures, this is in opposition to approaches that, like the static lifestyles theory, gave culture full power over the environment and the natural phenomena that formed the landforms and landscapes. Lucien Febvre’s questioning of Darwin’s theory of adaptation valued all cultures that imposed their law on nature [FEB 22]. Cultures would then derive their power from the fact that they do not adapt, and this inflexibility would be their strength.

A long-term relationship between a culture and a biome is exceptional. The taiga is considered an exception. The particular context of the taiga is one of limited exchanges with other cultures, and a very low population density, so that new entrants to this biome adopt the pre-existing culture. The very strong constraints of the environment play a part in explaining this particularism. Cultural diversity in a biome is the most common situation. In ancient climate theories, there is limited diversity, that of climates and therefore of cultures, but, in fact, diversity also occurs in each biome, where there are multiple cultures. Old climate theories have thus had a reductive representation of diversity. Montesquieu based his work on John Arbuthnot’s medical theories on the effects of heat on the human body. His consideration of climatic diversity was limited to the outdoor temperature variable alone.

Lucien Febvre [FEB 22] indicated the limits of approaches confined to geographical determinism, those of the Ratzel school strongly influenced by a social Darwinism. Today, it can be clarified whether or not approaches limited to trophic models, i.e. based solely on a chained succession of predations, are relevant: humans eat the mammoth that fed on vegetation, for example. A climate shock brutally reduced plant resources, then mammoth populations, then human populations. High climate volatility could be seen in proven cases of famine cannibalism, for example in the case of H. neanderthalensis (Baume Moula-Guercy site, 120 ka): the environment had changed in a few generations as a result of global warming, and H. neanderthalensis’ high-calorie diet led to recurrent famine, as directly reflected in a dentition marked by malnutrition. After 120,000 years, it is difficult to find situations of famine in historical times that are detached from an organizational or political economy dimension, or from a link with civil war or armed conflict. For situations of global warming, the great Irish famine of 1846 was linked to restrictions on trade in agricultural products, and the great Saharan famine of 1914 was linked to a sharing of the Sahara desert between colonial powers that imposed restrictions on people’s mobility. Severe environmental and climatic contexts see cultural adaptation determined by historical events and innovations. During the last maximum extension of the Sahara, the adaptive culture of the Garamantes was based on an urban system along an improved trans-Saharan road traversed by horse-drawn vehicles, tanks and heavy carts. The permanence of this urban system was based on defensive considerations: prosperous cities needed to resist warlike enterprises. Rome annexed this urban system, too weak defensively before the imperial armies. The transition from the horse to the camel, from the defensive urban system to a controlled commercial road, is understood as resulting from a major innovation, the introduction of camelids as a means of transport capable of escaping conventional strategies for controlling desert space. The great Saharan famine of 1914 led to the development of market gardening in oases located at high altitudes in the mountain ranges of the Sahara. Only the Nile Valley has survived as a trans-Saharan urban system, while towns have developed on the edge of the Sahelo-Saharan space, where different forms of pastoralism and nomadism coexist.

“The kind of life does not depend on the climate” ([FEB 22], p. 394). There is, however, according to Lucien Febvre, a kind of pastoral life corresponding to the hot arid biomes. However, according to the historian, new security conditions brought about by the “police”, i.e. the generalization of administrative control of populations, explain the reduction of nomadism: “what makes nomadism vary, what acts on it to restrict it, is a modification, not of the natural factors, but of the human factors of existence” ([FEB 22], p. 304). According to Febvre, the kind of life in arid environments would not experience famine, as it practices self-regulation of births. Historians’ interpretations of the events of the time provide a perspective on this quarrel between schools of human geography in the face of Darwin’s reception. Febvre’s assertion of the non-existence of famine in the Sahara can be understood in an anti-Darwinian doctrinal coherence that leaves no room for lethal selection with large episodes of mortality. Historians’ explanations of the 1914 famine in the Sahara highlight the combined effects of a rainfall deficit during 1911–1914 and the change resulting from the introduction of an administrative biopolitics, the only relevant one in Febvre’s approach to human geography.

Old climate theories remain confined to an internal explanation and avoid contingency explanations, which combine external and internal factors. The famine of 1914, as contemporary historians say, was the result of a particularly unwelcome conjunction of internal and external factors. The living area of the desert populations expanded due to the rainfall deficit, but this adaptation strategy was no longer possible due to a desire to control and limit displacement by the rival and then belligerent powers of World War I. Lucien Febvre’s fight against determinism does not leave room for an explanation by contingency, i.e. the combination of an internal factor (the organization’s culture) and an external factor (affecting the organization, such as a climate shock). The old static lifestyles theories are confined to explanations by a single factor, most often that of political will, which can do everything, for better or worse. For Febvre, determinism is not geographical, but subsists in an entirely political and cultural form. This approach to human geography does not avoid the shortcoming of being merely geopolitical, rejecting the notions of adaptation and the link between culture and climate.

In the human geography of Vidal de la Blache’s school, civilization is defined as a group of static lifestyles. The discussion opened up by Thomas Mann on the distinction between culture and civilization made it possible to clarify the relationship between the two notions. On this renewed conceptual basis, Norbert Elias developed a theory on the civilizational role of royal courts. Civilizational processes are those of cultures that contribute to a collective improvement in self-control and a general decline in social violence. In contrast to this theoretical elaboration, the notion of civilization finds a purely culturally aggregate definition in approaches to the decline of civilization, such as that of Samuel Huntington [HUN 97]. Huntington’s notion of civilization has lost all references to the notion of lifestyle, of cultural differences interwoven with environmental conditions, and refers mainly to the epic of a few cultures, at most seven or eight, that have endured. It is stated in opposition to Elias’ approach, since the end of the Cold War is situated in a context of a global decrease in social violence in the long term, thus in a civilizational process that obviously is no longer the same as that of the Sun King’s court in Versailles. The Clash of Civilizations [HUN 97] speculates that this civilizing trend cannot continue by painting a pessimistic picture of the evolution of international relations after the Cold War. The most tragic conflict of the time, the Rwandan genocide of 1994, was not analyzed by Huntington, who therefore did not carry out a risk analysis based on the major conflicts after the end of the Cold War. Rules of engagement emerge in this period around military interventions justified by the existence of internal political support in the country concerned and by a duty to protect civilian populations subjected to large-scale massacres. Huntington contrasts this universal, multilateral conception of collective security, which calls for a reorganization of the existing armed forces around the new threats, with a division of the world into large areas, each subject to competition for regional supremacy.

Contrary to Samuel Huntington’s predictions of the clash of civilizations following the opposition of the two Cold War blocs, it is the internal divisions within the different major areas under consideration that form the sources of major conflicts: the competition for regional leadership within the Muslim world between Saudi Arabia and Iran, or the claims of the Moscow Patriarchate over the Ukrainian churches within Orthodox Christianity. The areas of major conflict at the end of the Cold War were little different from those of today, with the exception of the wars resulting from the break-up of the Yugoslav state.

Figure C.1. Major conflicts in 2018 and map of civilizational shocks projected by Samuel Huntington. Source: [HUN 97], p. 364. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/alaktif/climate.zip

Samuel Huntington’s delineation of areas of influence is unfavorable to African populations, Muslim populations and Europe, which is not even considered a distinct “civilization”. Huntington’s book calls for Europe to withdraw from the Balkan area, due to a new Yalta, with the re-establishment of the Trans-European Wall on a new dividing line from Zagreb to Tallinn crossing the territories of the former Yugoslavia and Ukraine. The proposals of a world organized militarily into seven or eight major regional powers would make it intrinsically very unstable. In addition to the internal conflicts within these regional groupings, there are also those of a competition for regional supremacy, and those of major conflicts between regional powers. Contrary to Huntington’s recommendations, a multilateral solution and a NATO commitment were used to resolve the conflicts arising from the break-up of Yugoslavia, which effectively allowed peace to be restored.

C.1.2. Contingent collapses

How do cultures or civilizations disappear? The Newfoundland offshore cod fishery is probably one of the simplest situations of collapse that can be contemplated: specialized predation in a marine area dedicated to this activity. The fish stock collapsed in 1992, resulting in the closure of the Newfoundland Bank fishery, and has been struggling to recover since. But even in this very simple case, the explanation can only be contingent, in the sense that not only natural conditions intervene, but also the modeling of the cod stock by the fisheries department and the forms of social negotiation and accommodation in the setting of and compliance with annual allowable catch quotas.

Contingent collapses in the most analyzed island systems are those of Easter Island, and Greenland and Vinland in Viking times. Island systems take the form of a core, a subset of an archipelago of exchanges restricted to a limited number of islands, and a natural space, most of the islands in the world being without inhabitants. There was maritime expansion of the Polynesian Islands, and the Vikings experienced a maximum expansion and then a phase of retreat. The contingent collapse affected territories that were the most difficult to access. It was achieved through a gradual reduction in trade with these territories that were forced to survive in autarky and endogamy, with an internal increase in pressure on limited local resources, leading to a gradual disappearance of the human population within a few generations.

Contingent collapses of urban systems are of two types around an intermediate configuration of the urban hierarchy, one corresponding to a rank-size law with a coefficient equal to 1.

The situations of agglomerations for values above 1 correspond to poorly structured urban fabrics with many equivalent entities. The urban system of the Garamantes, with small forts at equal distances to serve as relays and shelter for horse-drawn carriages crossing the Sahara, is an example. It was absorbed by the Roman urban system, whose agglomerations were more diverse in size. The civilization of Obeid was one that preceded the appearance of the Mesopotamian urban polyarchy. These were large, wealthy homes of landowners, spread over a vast territory. The very same agglomerations were not conducive to trade, since the same little varied supply was simply scattered over a territory. A dynamic of collapse was seen in this system of strictly equivalent conurbations, leading to the emergence of an urban polyarchy system that regained the reference value of the coefficient of rank-size law. There was no standard human settlement, and urban systems, for example, initially composed of the identical reproduction of an urban size or farms, were evolving towards a level of equilibrium diversity.

Networks of towns with a coefficient value less than 1 correspond to a very strong urban hierarchy, an oversized megalopolis compared to generally very small agglomerations, with few intermediate situations. In this case, the contingent collapse is towards an urban system with a more tiered size diversity. This was the case for the end of the Hittite empire, with the voluntary and unexplained abandonment of the capital Hattousa, or for the gradual disaffection of the Angkor site. These large metropolises weighed too much on their immediate environment and posed problems of supply, maintenance and management.

There are two types of contingent collapses linked to monsoon regimes: the “deluge” type linked to a greater volatility of heavy rains, and the “dragon” type linked to a spatial shift in the monsoon zone. A shift in the demarcation of monsoon zones explains, for example, the alternation between a green Sahara and a desert (contingent collapse dragon type). Disruptions in the timing and volume of rainfall were associated, for example, with dynastic transitions in the Chinese Empire [ZHA 08] (examples of the flood type).

Saharan cultures have succeeded one another according to desert formation episodes. The main sequence consisted of three cultural phases. For a phase of stability after an initial drop in rainfall, the rock paintings present were those of the “Round Heads”, anthropomorphic art, with the beginning of representations of orants, indicating a cultural transition towards the sacrificial. More power was given to shamanic trances. Artistic activities multiplyed in a culture that, in our opinion, seemed very festive. The next episode was that of the bovine cultures, the development of a pastoralism starting from the domestication of aurochs. Large herds of cattle were then present in an open landscape with rainfall that was still relatively high. The definitive installation of the desert concerns representations of horse-drawn chariots. This was the culture of the Garamantes, a Berber word meaning “fortified city”. Trans-Saharan trade was the most prosperous at the maximum extent of the desert. In Antiquity, this was the trade route that supplied wild animals for circus games. Then came the camel caravans. This situation, which corresponded to the cultural areas of the dragon, was also that of the Indus civilization, whose disappearance was due to a change in the course of rivers in a long period of drought. Smaller contingent collapses occurred in cultural areas that were native to flood myths, such as the succession of civilizations in Mesoamerica or China.

Contingent collapses can be associated with biased expectations of system resilience. The simple case of the fishery depleting the fish stock represents a situation of optimistic bias: the anticipated resilience of the system has been judged to be greater than it actually is. This bias may stem from the system of negotiation and governance of the fishery, the forecasting model used and the anticipated resilience, i.e. the estimated speed of stock recomposition by fishermen. It may be that among the many cases of urban site abandonment, for example in Mesoamerica, Asia or Anatolia, some are the result of a pessimistic bias on the resilience of the system. An urban system is considered too fragile by the decision-maker of the time, to the astonishment of the contemporary archaeologist who notes a site abandonment in a rather favorable general situation.

C.1.3. From spirituality to academia

Today, the only cultural current that has taken a public stand against the reality of man-made climatic instability is that of some of the evangelical churches of the Bible Belt in the United States, based on a literal interpretation of the book of Genesis. This contemporary opposition, the denial of climate change, is however made when faced with a consensual basis: the representatives of the major religions, as well as all the planet’s countries, have given their support to the Paris Agreements of 2015. In its opposition to the rest of the world, Trump’s administration relies on a “creationist” electorate that polls have shown to be more sensitive to supporters of climate denial [ECK 17]. These same surveys indicate that “creationism” (thinking the world is newly created) is more widespread than “climatoscepticism”, but that it is also of older introduction, dating from the beginning of the 20th Century.

A doctrine of creation is thus at the core of the opposition to the Paris climate agreements. How can a creative myth work against creativity? Two ancient approaches have tried to explain this situation. The first is that of Durkheim, when he developed the idea that spiritual and cultural movements go through two phases: a first phase which gives the initial impulse, then a second phase which is content to manage the Church which was formed in the first phase. Creativity is a straw fire, then comes the time of commemorative rituals, the time of creation myths. The second approach is that offered by Dewey, where creative myths are not consistent with the realities of creativity and discourage access to it. The work of paleoanthropologists and prehistorians is moving away from the concepts of Durkheim and Dewey. The emergence of creative myths brought cultural diversity at the time of the transition to the Upper Paleolithic and thus consecrated human creativity through the multiplication of the arts. In Durkheim’s work, culture and religion are the result of entirely social dynamics, without the influence of climate [DUR 12]. In periods of high climate volatility, as was the case in the Paleolithic period, prehistory is not without history, since climatic events mark the cultures of human groups, altering or assisting their survival. For Durkheim, the Ice Age populations lived in isolation most of the time, and could only recognize themselves in a totem pole. They only experienced effervescence during rare gatherings, the only events conducive to the emergence of a symbolic religion by federation [DUR 12]. The Durkheimian approach to the emergence of new cultures would be best supported by a situation where major faiths would be in opposition to novelty, while emerging cultural and spiritual currents would carry practices conducive to creativity. In surveys conducted in the United States, the two largest cultural or religious groups (people of no declared religion and Catholics) are strongly positive about the fight against climate change. Climate scepticism has developed in a partisan dynamic, around the Republican Party, with leaders of mining and oil companies and lobbyists specialized in the denigration of environmental concerns as animating circles. “We believe that Earth and its ecosystems – created by God’s intelligent design and infinite power [...] are robust, resilient, self-regulating, and self-correcting, admirably suited for human flourishing [...] Recent global warming is one of many natural cycles of warming and cooling in geologic history” (Cornwall Alliance Statement, December 2, 2009). God is the only omnipotent creator, so there can be no creativity of his own for man. The book of Genesis is considered the foundation for faith (Doctrine of the Assemblies of God, 2010).

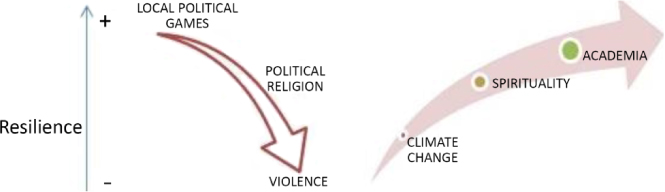

Figure C.2. Salient links in Sahel surveys: bottom-up and top-down logic of resilience

The expression of this climatic providentialism indicates another inadequacy of Durkheim’s approaches: if cultures or religions are defined only by a social process, the content results only from an ability to bring people together: “since religious force is nothing other than the collective and anonymous force of the clan” [DUR 12]. It is a question of generating cohesion, without taking into account the severe contexts induced by climate change, the extinction of species and after-effects on genetic heritage for example. The development of “climate scepticism” has occurred in relation to the timing of climate negotiations. A first wave of climatic scepticism took place between 1988 and 1997 with a partisan anchoring of positions: the US negotiator being a Democrat, the opposing party, a Republican, became polarized in a radical anti-environmentalism. The second “climatosceptic” campaign is being conducted as it is a question of defining the post-Kyoto period, and the US negotiator is once again from the Democratic Party [NOR 19].

Previous surveys conducted in the Sahel [CAL 14], as well as the conclusions of the first part of this book, highlight two series that have little in common. These two series represent the bearish and bullish logics of resilience. The rise of social violence and its long-term settlement reduces trust between people and breaks down social empathy that facilitates resilience. This loss of resilience occurred after the Upper Paleolithic.

Political violence is that of war contractors. For example, contemporary climate change is reducing the size of Lake Chad, allowing for the development of fertile agricultural land in the landlocked areas. These enriched areas have become the target of the Boko Haram* militias since 2014. The itinerary of the latter is schematically that of involvement in the local political game, then the orientation in the development of a “political religion”, as discussed by Bentile. This political religion is considerably amplified by political violence. Similarly, the rallying of Targuis notables to jihadism is based on local political considerations, and on the fact that these local elite families had not anticipated new social rules of the game, those resulting from the schooling of children, including those from aristocratic families [BAR 13]. The “low-level education” contained in the expression “boko haram” (meaning, word-for-word, “books are sins”) is part of this renewal of elite training courses. The rejection is that of academia, school and university training, hence the dichotomy highlighted in Figure C.2.

On the side of factors conducive to improving resilience, in addition to a decrease in social violence, there are factors that result from learning (management of extreme events, education, positive philosophy of life) and local policies (inclusion, openness and anticipation of extreme events). A chain links climatic instability to the development of spirituality. The primary affirmation of spirituality, whatever definition is used, takes place at a time of great climatic instability. Defining spirituality in Foucault’s way allows us to indicate the link between spirituality and academia. A lowering of the costs of self-transformation in creativity and truth production results in leaving only academic work as the cost of creativity and truth production. The major dynamics of resilience were first its installation and improvement, its degradation by an increase in social violence, and, second, a reduction in the costs of producing and transmitting reduced resilience.

C.1.4. Resilience in Sustainable Development Goals (2015–2030)

“Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries” is the first objective of the measures to combat climate change, which constitute point 13 of the United Nations global plan for the period 2015–2030, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This complements the Paris Agreements by setting up monitoring indicators, making the Green Climate Fund operational, and building capacity. The provisions currently in force in the fight against climate change are based on two pillars, mitigation and adaptation, in a funding scheme that is philanthropic in nature. In practice, there are a significant number of “green” foundations with varying statuses (private, unilaterally public, bilateral and multilateral) that fund action programs that they select in a decentralized manner. The two main texts structuring these provisions are those of the Paris Agreement and SDG 13, which aims to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. The financial target set by SDG 13 is a green fund of $100 billion per year by 2020 to “address the needs of developing countries for concrete mitigation actions”. In practice, it has been noted that financial commitments today are made in the areas of mitigation (reducing greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation (taking immediate action in the face of threats caused by climate change, or repairing their effects). Public policies in France are currently being implemented with financial commitments of approximately 20% for adaptation and resilience, and 80% for mitigation. The 12 December 2017 Green Finance Summit endorsed a global commitment to scale up financing for climate change adaptation.

Resilience, as a seamless journey through great hardship and positive rebound, and the fight against climate change were not mobilized in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the objectives of the international community for the period 2000–2015. Preliminary discussions about SDGs have tended to dismiss the health dimensions, particularly mental health, which are very much present in contemporary post-disaster interventions. Health themes had been strongly emphasized for the MDGs, while the SDGs deploy environmental policy objectives. This inclusion of climate change on the global agenda was therefore slow to emerge (scarcely present on the MDG agenda), and when it was put on the agenda, it tended to overlook what was at the intersection of health and resilience approaches [CAL 16].

C.2. Political violence and the sacralization of a culture

An initial study on the climatic instability of the Sahelian zone and its consequences in terms of conflict concluded that a political cycle, Hirschmann’s cycle, was the result of an alternation between public commitment and the search for private happiness, which is also known from elsewhere [CAL 14]. In a long-term history of climate change, extremes of climate and social violence do not coincide. Social violence was at its peak with totalitarian regimes and the two world wars at the beginning of the 20th Century, while the focus on the climate change agenda began with the Rio Summit in 1992. There did not seem to have been a strong conflict in the Upper Paleolithic, as it was only in the period after the rise in sea level that there were archaeological traces of violence committed, humans against humans. The great phases of social violence, such as the arrival of weapons in the Bronze Age and then with the mastery of iron metallurgy, took place on dates without any entry in the calendar of climatic events. Collective violence and climate appear as substitutes in a broad vision: the relationships of extreme natural events leave the chronicles when a period of war begins, to reappear afterwards. While climatic weathering is significant and affects all regions, crops either deteriorate following survival behaviors or technological elements are developed that are already mastered. Social violence usually implies that somewhere there is a granary to be plundered, a condition that was not really fulfilled in major climate crises. Adaptation to climate change is a cost to be minimized, and paying a bill has never led to major conflict, but to evasion of responsibility.

C.2.1. From Montesquieu to Eliade

Eliade’s formulations support a paroxysm of social violence, that of the Fascist period, in the political religion approach, to use Emilio Gentile’s terminology. Eliade’s formulations call for a detailed interpretation of the reconstructions of his religion of origins, the orientations of his history of religions having been fixed as soon as Eliade’s participation in the Iron Guard, the Romanian fascist movement. Political religious movements rely on collective rituals and paramilitary organization. The destabilizing action of the Iron Guard led Romania to fall into a succession of dictatorships, first in the orbit of Nazi Germany, then that of the USSR, between 1938 and 1989.

Eliade can thus be compared with Montesquieu and the ideas of parliamentary representation and freedom of conscience, of a lack of syncretic aspiration to the formation of a national religion, in the sense that the public authorities should not impel a new religion of their own making, unlike these political religions, which can be considered as fully formed in Eliade’s generation.

In Montesquieu’s climate theory, he states an alternative, “1 or N” in religious policy. Public policy does not have to encourage the proselytizing of a new conquering religion, and must tolerate all established religions ([MON 51], p. 744). Sometimes there is only one, sometimes there are several. The formation of Greater Romania corresponds well to this second scenario: the new territorial entity resulting from the end of World War I brought together a wider confessional diversity than the pre-war entity of 1914–1918. Montesquieu’s climate theory belongs to a political science line of thought, and values the role of an independent judiciary and political intermediation. Montesquieu, a great landowner, was himself a member of the Bordeaux Parliament. In Montesquieu’s case, one of the branches of the alternative imposes itself, whether or not there is a religious “natural monopoly”. The Romanian Constitution of 1923 was an attempt to escape this alternative. It set out a hierarchical plurality of confessional statutes in Article 22 – “the State guarantees to all religions equal freedom and protection” – and then defined two specific regimes of Romanian churches, one, autocephalous, called “dominant”, and the other, Greek-Catholic, “with precedence over other religions”. This 1923 Constitution of the Great Romania organized religions in a three-tiered scheme: at the very top, the Orthodox religion of the Patriarchate of Bucharest, then the Greek-Catholic religion, and finally all the other religions.

Montesquieu can be placed in the lineage of political science as he provided critical analyses on previous mercantilisms. For example, Montchrestien’s Traité de l’économie politique [MON 99] places itself within the framework of an official syncretic religion, a political religion of cults which makes each Prince coincide with a unique Religion over which he has authority. Montchrestien’s statement of the formula “what one gains, the other loses” was made with a Gallican religious policy, strongly hostile to an independent religious authority and to foreigners. The 19th Century positivist revived a syncretic aspiration: Comte intended to be the Pope of a new religion of humanity, this time detached from Gallicanism. It was a question of re-establishing a moral authority that has been judged to have disappeared. Contemporary historiography of the inter-war period in Central Europe focused on the interplay between aspects of political and religious life and the rise of fascism [SAN 10]. Gentile [GEN 05] pointed to a sacralization of politics that was generally expressed through nationalism. This radicalization existed in several regions of the world in the same historical period. The term “kamikaze”, which was introduced by Japanese militarism, refers in a very symbolic way to a meteorological phenomenon, the West Wind, in an instrumentalization of an animist religion by armed forces.

In Romania, Article 22 of the 1923 Constitution of the Great Romania is eclectic, adding different regimes of religions (freedom of conscience and a State protecting religions, plus two Romanian Churches, one autocephalous, the other uniate), as well as incomplete, not specifying the role of the sovereign of Romania in religious matters. Persons of the Jewish faith in this 1923 Constitution were under a regime of freedom of worship and full citizenship. On the model of Charles Maurras’ Action française, an anti-Semitic party was created in Romania in 1923. Action française was condemned by Rome in 1926, condemnation of a political religion which concerned the instrumentalization of the Catholic religion, threatened directly from the outside with the fascist power in Italy, and from the inside by some of the hierarchy acquired to the Action française cause. The legionary movement of Codreanu that was created in 1927 in Romania was a fascist movement, the Legion of Archangel Michael in its initial denomination, known especially for the Iron Guard, the paramilitary groups that emanated from it. As with Action française, a recruitment strategy among the clergy was implemented. Historical criticism today undermines the socio-economic explanations for the emergence of these paramilitary groups, since the economic situation was positive and could not induce an essentially messianic and apocalyptic movement (the title of the movement is a reference to a phrase from the Apocalypse of John of Patmos (12, 7–8)).

Emilio Gentile’s synthesis invites us to reconsider in detail all forms of “political religion”, in their practices and justifications. The intellectual biography of Mircea Eliade is questioned in this research program from three perspectives: a strictly historical perspective on his links with the legionary movement between 1934 and 1944 [LAI 02; GAR 12] and investigations into the interference between fascist engagement and approaches in the history of religions [GRO 05]. Questions are also raised about the impact of this dark episode in Mircea Eliade’s intellectual journey [SAN 10], and about the organizing concepts (such as “traditionalism” or “fundamentalism”, to which the notion of “political sacralization of a culture” is preferred) in a typology of “political religions”.

“Political religion” is defined in violation of the two principles laid down by Montesquieu:

- – the principle of neutrality expressed by the absence of political support provided to a new religion generally instigated by an existing power or political party;

- – the principle of diversity, where the State is the protector of all religions. They are established on an equal footing and are committed to peaceful interreligious coexistence.

These principles were not fully and clearly established in the Romanian Constitution of 1923, which was suspended in 1937. A repression phase in the legionary movement in 1938 led to the temporary administrative internment of Mircea Eliade. The political and international crisis led to the disintegration of Greater Romania soon afterwards. Messianic and apocalyptic currents are macroeconomically pro-cyclical: a phase of prosperity brings new inventions that are widely disseminated and feed apocalyptic discourses on the approaching end of the world due to the multiplication of the use of these new inventions and the acceleration of social mobility. Contrary to this favorable situation, the principles enunciated by Montesquieu had been put forward with the vector of a resilient group, that of an export agriculture, on the occasion of a particularly disastrous situation during the climatic cooling at the end of the 17th Century, combining the bankruptcy of public finances and famine episodes.

C.2.2. Eliade, the first humans and the climate

In the terminology of religious studies, Montesquieu and Eliade were comparatists, in the sense that they sought a general theory of culture. Montesquieu studied the relationship between cultural and legal norms in relation to various constraining factors such as the climate. Normativity is the result of the balancing of several powers. Eliade’s work is based on a phenomenology of religious experiences, which human societies sometimes lose and then rediscover: great archetypes are buried in the depths of the human mind, and sometimes reappear according to historical and environmental contingencies. In Eliade’s work, the relationship with the environment is symbolic or pictorial, while the mediation is that of a religious life. Rituals reactivate a primary interaction of humans with the environment, human action “becoming real, only because it repeats an archetype” ([ELI 64], p. 41).

Mircea Eliade’s synthesis on water myths favored flood myths, so much so that a question arose as to the disappearance in his writings of the mythical figure of the dragon, the hydrophilic figure. The texts published by Eliade, however, reserve a place for the dragon only in the Asian worlds. However, the phylogeny of tales and myths initiated by Tehrani [TER 13] overturns this priority given to flood myths, pointing to a great antiquity of myths associated with the dragon, more appropriate to climatic and geological contexts experiencing devastating droughts and flash floods. Romania has a long tradition of dragon cults, which Eliade could not ignore, having himself been part of a fascist movement for 10 years that referred to the fight against the dragon in its official name, the Legion of the Archangel Saint Michael. The ancient world was aware of the importance of dragon worship for the people of the Danube Delta: the Roman troops who frequented the Daces were quick to add a dragon to the usual eagle of the imperial armies. Eliade thus proceeded to a selective voluntary reconstruction of the ancient religions, presenting a syncretic character, but not taking into account entire sections of the oldest beliefs.

Climate theories were gradually abandoned in the 19th Century. While Auguste Comte’s positivism partly retains a climate approach in its preservation of Hippocratic principles in medicine, the social sciences have increasingly focused on social processes independent of climatic circumstances. Pure dynamics of human aggregation explain the progress of sociability through urbanization in Comte’s work, then all the foundations of societies and religions in Durkheim [DUR 12].

Montesquieu’s life was part of a climatic experience, that of the cold weathering of the late 17th and early 18th Centuries, which is no longer the case for his successors. The Bordeaux vineyard expanded during the cold climate phase. The gravel terraces, the Graves, of the Garonne located further south were covered with vines, giving a centrality to Montesquieu’s land in the Bordeaux vineyards, whereas today this epicenter is located further north. The creation of the Bordeaux Parliament supported this phase of expansion towards the south of the Bordeaux vineyards, with large estates exporting mainly to Northern Europe. Cold climate weathering brought tensions between the Parliament of Bordeaux and the Royal Intendant, the latter wanting to return to food-producing agriculture because of the food shortages and famines affecting the population. Faced with tax reform projects, such as Vauban’s single proportional and universal tax, Montesquieu theorized the role of political mediation and its procedures. The climate, according to Montesquieu, reduces moral freedom for high or low latitudes, and the spirit of the laws is understood as a skillful composition of the legislator from this human diversity.

Elijah’s Patterns in Comparative Religion [ELI 64] has chapters according to themes of symbols, such as the sun, waters and vegetation. No distinction is made according to time or type of site (e.g. arid or mountainous environments). The sources used are those of oral traditions collected by folklorists and ethnologists. Hunting myths are not addressed, while agricultural myths are.

Contemporary questions on the history of climate change use archaeological processes, genealogies of myths and genetic reconstitution of the spread of the first human populations. All of these processes provide dates, with significant intervals of uncertainty. A central hypothesis of paleoanthropological research is the existence of a link between the formation of cumulative cultures by early man and the context of very high climatic instability. This context is that of Ice Ages with much more unstable climates than in interglacial periods. The first human cultures were situated in a context of strong climatic instability, and logically they saw themselves as having to insert themselves into the powers of nature. An important turning point in these early climate cultures was the shift from conceptions where the world was seen as flowing, with a great force that ensured its cohesion and specialized natural powers that maintained the balance [CLO 11], to one where there was a climate god with sometimes excessive interventionism.

The history of religions as an academic discipline had been oriented towards a perspective of religious sociology following what was called the “modernist crisis”* of 1908, the condemnation by Rome of the teaching of religious sciences based on free research in Catholic universities. From the perspective of a religious sociology, the dynamics were those of human aggregations without taking into account the environmental context and the distribution of extreme natural events. For Durkheim, either the human group was small and referred to a totem pole, or it aggregated and generated an “international” effervescence, as Durkheim said, itself generating a more elaborate form of religion, closer to organized worship [DUR 12]. On the side of the Roman Catholic papacy, Schmidt’s theory of original monotheism is the only survivor of the anti-modernist purge: a higher power was understood to have been venerated at all times. For Schmidt, there would have existed only one deity at the beginnings of religion, then there would have been a multiplication of sacred powers. Durkheim and Schmidt discussed an original religion based on the beliefs of Australia’s aborigines. For Eliade, “the structure of religious experience changes” with an evolution that “always marks the victory of dynamic, dramatic forms, rich in mythical valences, over the supreme, noble, but passive and distant Celestial Being” ([ELI 64], p. 57). Eliade stated that “cultic poverty is a characteristic of the majority of the heavenly gods” (ibid., p. 52), presumably to refute the aggregative dynamics of religious sociology, the ritual and mythological content increasing with the grouping of clans according to Durkheim [DUR 12]. Eliad’s theory on a celestial deity that is at first idle, then replaced by a more active one, is based on a measurement of the frequency of rituals. A divinity linked to rare events was judged by Mircea Eliade as idle, since it is linked to infrequent experiences: “men remember Heaven and the supreme divinity only when a danger (...) threatens them directly; the rest of the time their religiosity is solicited by daily needs” ([ELI 64], p. 55). For Eliade, religiousness can be found in repetition, and places itself outside contingency, which would only come later with the historical epochs. For contemporary studies, the sequence of phases would rather be the reverse of that proposed by Eliade: the Paleolithic is interesting because it was rich in abrupt climatic events, whereas historical periods have comparatively little climate volatility until recently with contemporary climate change.

Eliade, in relation to Durkheim and Schmidt, introduced the concept of the transformation of religious experience. But it is used in a single caesura schema, in a transformation towards cultures that are generally polytheistic, with hyperactive gods. The Sibylline books, a collection of rituals for exceptional situations, were abandoned by the ancient Romans in the 4th Century AD in a new religious transformation, that of late antiquity.

High climate volatility has contributed to the formation of the cultural fund of humanity. Dating the passage to societies where sacrifice played a primary role is an ancient concern, fuelled by the discovery of the Lascaux cave. In Eliade’s work, sacrifice is defined from its general pattern of archetype repetition. The ritual according to Eliade replays the scene of creation. Only if this creation is a sacrifice will the ritual entail sacrifice. Important developments have been made by major contributions on the theme of sacrifice in the history of religion, from James Frazer to Luc de Heusch. This is not the case for Eliade, who merely recalled the general framework of analysis around the ritual, the archetype and its repetition.

Eliade’s religious phenomenology appears selective, specializing in mysticism. In a survey of shamanic practices in Japan, Blacker [BLA 99] indicates that two types of shamanism coexist, the medium and the ascetic, but that the second is by far the most common. Eliade helped to establish a conception of the shaman primarily as a medium. Eliade’s academic thesis [ELI 75] dealt with ascetic breathing techniques, yet it focused on mediation with the sacred. This priority given to interpretation on the side of mystical practices was quite widely shared in the religious sciences at the beginning of the 20th Century. The mystery cults of Greco-Roman antiquity had served as the key to the beginnings of Christianity. These esoteric and insider practices were generally on the fringe of existing cults: they became central to Eliade, while the exceptional rituals of great natural events were moreover sidelined.

However, major enlightened rituals carried out on a regular basis are probably the result of an intensification resulting from a situation of unprecedented distress. Clastres insisted that the great caesura is the one that brought about historical and political societies, but with a contrary assessment to that of Eliade. It is difficult to imagine a more exemplary illustration of a great ritual of re-creation of the world and of humanity than that of the Mandans (a ritual cited in [ELI 57], pp. 253–254), but for Clastres, it testifies to the impasse in which these stateless societies remained submerged by a social violence that did not allow them to overcome the new challenges they were facing [CLA 74].

The main sources used by Eliade pre-date the discovery of the Lascaux cave in 1940. The connection between the Lascaux paintings and shamanic practices was made by Glory, who was in charge of the site in the early 1960s. Eliade, neither in Patterns or in his work in general, specifically addressed the Paleolithic or climate theology. The questions of the first half of the 20th Century focused on the heterogeneity of the beliefs of the Aboriginal Australian populations and the religious rituals recognized elsewhere. The sources were exclusively folkloric and ethnographic, with comparatism seeking to produce a synthesis from these different corpora. The usual distinctions of the prehistorians, introduced as early as 1842 by Boucher de Perthes, between the Paleolithic, Neolithic* and Metal Ages are not used in works that combine only religious phenomenology and sociology. No event, no history and no climate: Eliade’s concerns were those of a day after the Russian revolution that abolished the established religion of orthodox ritual, an event that was a vector of aspirations for a religious recovery and renewal, for which we need to find both the impetus and the processes of reinvigoration.

C.3. A new climate theory

Let us recall some of Montesquieu’s formulations: “The more the climate leads people to flee from work, the more religion and laws must excite them”, and in particular, “in Asia, the number of dervishes seems to increase with the heat of the climate”, just like those monks “in the south of Europe”, “who live in abundance” and “rightly give their superfluous things to the lower people” ([MON 51], I, pp. 245–246). The spirit of the laws is that of social correction in an environmental and climatic context. This presupposes two types of social processes: conventions resulting from the climatic context that modify characters and emotions, and a complementary process that makes it possible to achieve good social functioning. A pure sociological law theory would recognize the creation of the social norm only through an interaction between actors (i.e. without a climate), whereas a moralistic or legalistic legal instrument requires the prior existence of a set of prescriptions (also without a climate). Sima Qian says that the first emperor of China chose the number 6, and all things then needed to refer to this value as a module of measurement, and this defined for him legism. The spirit of laws is neither sociology nor legism.

Some bad ideas come from reductive visions of climate theory. They all come back to the claim of a “hyper”-culture summarizing, reappearing or imposing itself on all the others. In positivism, all cultures must evolve towards the universal syncretism of a religion of humanity. The mathematical series of a number of cultures would converge in the future towards the value 1. In human geography theories, the notion of a kind of lifestyle bijectively associating a biome with a culture, for example, pastoralism for the desert, drastically reduces the diversity of human cultures. This process of cultural “cartelization” is found in geopolitical writings, with as much generosity for the human species and its diversity as the first emperor of China. Religious phenomenology, on the other hand, presupposes an initial imprint of environmental elements that would resurface from time to time, and man would never be anything more than the unconscious prisoner of the imagination of his first contact with natural phenomena.

Large-scale natural phenomena have long gone unnoticed. The catalog of these very large phenomena, such as climate change, began to be established during the 20th Century, particularly through satellite observation and interplanetary comparisons. Montesquieu’s work thus still bears witness to a long-standing relationship with the climate, as the owner of a winery, very attentive to small seasonal variations as well as an indicator as volatile as the selling price of Bordeaux wine, and for the rest distinguishing cold, hot or temperate climates. It is situated in a theoretical framework inherited from Aristotle, with a comparison of three types of political regimes, without intermediaries between public agencies and individuals. He was neither social nor democratic, protesting against the idea of tax equality proposed by many tax reformers, following Vauban and his plan for a royal tithe. Montesquieu mainly retained the bankruptcy of public finances in France from the climatic accident of the Little Ice Age, but relied solely on indirect taxes paid by commercial intermediaries to ensure budget revenues.

The positive aspect of culture or religion for Montesquieu was “excitement” at work. This was modulated according to the climate. A trap of maladjustment and voluntary poverty could appear and persist in hot countries, when too many generously maintained monks allowed themselves to cultivate their popularity by giving back an unconsumed surplus, so that “the lowly people manage to love their own misery” ([MON 51], I, p. 246). A moral constraint should be stronger in a hot country, but this context is also, according to Montesquieu, the one that generated monasticism. Montesquieu was neither a culturalist, in the sense that all cultures are equal, nor a cultural evolutionist, for whom cultures would progress through different measurable stages on a universal scale. A “good” culture is, according to his climate theory, one that provides “excitement” adapted to the climatic context.

The current state of global arrangements for climate change is the result of the existence of “free-riders” and the search for “excitement” adapted to the climate context. The problem of “excitement” is a necessary one due to the gap between the voluntary commitments of the countries of the Paris Agreement, whose practical translation gives a value of about 4° at the end of the century, and the stated objective of limiting it to 1.5°. The “free-rider” problem is the pro-carbon club, which has gradually reduced in size, but of which the current Trump administration remains.

C.3.1. Free-riders

The free-rider problem is posed by a situation where someone takes advantage of a benefit obtained by a collective effort without contributing to it or by moderating their participation in relation to other contributors. For climate change, the question arises for mitigation, with everyone benefiting from the decrease in carbon emissions, with the latter playing an overall role in moderating climate change, which can provide an incentive to let others make the greatest effort, while benefiting from the efforts of others. For the second strand of climate change policies, that of adaptation, the situation is different. If a community is threatened by a flood or flooding, the issue is to find the funding to pay for the necessary work or compensate the displaced. A decrease in community effort can be very severely punished with catastrophic consequences.

A situation of budgetary compensation, where the free-rider contributes less in one area and is asked to make a compensatory effort in another, does not have the multiple disadvantages of resorting to “green protectionism”, especially since the situation under the Paris Agreements is that of an already protectionist shirker, with a greater risk of escalating trade retaliation. For each of the drawbacks of “green protectionism”, solutions can be devised to avoid this drift.

Global agencies are specialized conflict resolution bodies in the area of agent competency for trade, but there is nothing like them for climate change. There is no World Environment Organization, with a global jurisdiction specializing in environmental conflicts. Aggressive trade policies are confronted with the existence of World Trade Organization procedures. Anti-environmental policies do not have this kind of obstacle. A preferable proposal to that of “green protectionism” is the creation and strengthening of a global environmental agency with jurisdictional powers. “Green protectionism” would result from a breakdown of the existing multilateral framework, whereas the opposite is necessary.

Protectionism is based on the forms of cartelization of the economy and the strengthening of barriers to market entry. It serves the interests of established firms and harms innovative green firms, i.e. it is part of the delaying tactics delaying the energy and ecological transition. In terms of the energy transition, it helps to promote rentier companies, particularly those specializing in hydrocarbons and coal.

In the specific area of trade, a policy of freedom of establishment for innovative green firms is preferable to “green protectionism” for climate, intergenerational and spatial justice. The new generations are the greatest victims of isolationist rentier policies, as evidenced, for example, by the situation of young Algerians under the Bouteflika regime. As far as the spatial dimension is concerned, a continent such as Africa is the only one to remain a major user of renewable energies. The populations do not consume the too expensive energy from hydrocarbons, which is therefore mainly sold for export. Moreover, the continent bears significant costs of adaptation, and green protectionism would thus be a solution that would impose additional costs on the victims of climate change.

After the Paris Agreements, the price of coal fell, so that developing and emerging countries bought coal-fired power plants with loans from major financial institutions. It was more a matter of acting with these development banks rather than restricting trade.

Green protectionism is an encouragement to widespread transgression. The transgression of trade rules creates an area without legitimate order. Rather, transgressions should take place within an inclusive space of civil society, as Kant argued.

Protectionism fuels tensions, encourages extreme violence and contributes to instability and major conflicts. The Trump administration policy is causing a surge in the purchase of military equipment, a public expenditure that would be much better used for social and environmental protection policies.

Protectionism is not a policy of adapting to dry weathering. The crisis of 1929 took on its full magnitude because of a rejection in the 1920s of adaptive agro-environmental policies in the face of the drought affecting the western United States. These measures were taken from the second half of the 1930s onwards, but in the meantime protectionist policies caused the entire world economy to plunge. These agri-environmental measures could have been taken earlier, avoiding the spread of the crisis through protectionist provisions. Adaptation is based on policies implemented locally in solidarity with the agricultural community.

Protectionism is inappropriate from the perspective of differences in climate change. Protectionism developed in cold weather and then contributed to violent conflicts, famines and major economic crises when reused for dry phases. The context of the emergence of mercantilism/protectionism is that of agricultural economies heavily impacted by a trend towards climate cooling. The cold came in catastrophic episodes, interminable winters that led to a shortage of food between two harvests, with their share of famines. Local administrators made regulations to limit prices, restrict the movement of agricultural products and encourage market gardening on the outskirts of towns. The United Provinces of the 17th Century were the prototype of a mercantile state, with the close interweaving of merchants and politicians. Resilient groups were transgressive of urban self-sufficiency injunctions based on export agriculture. The vineyard map in France stabilized during this period, with a decline in production in the north, and development driven by the export of vineyards in the south, such as the Bordeaux vineyards. The climatic cooling of the Little Ice Age led to a flow of investment to the south, so that the central question of Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws is: how can we put the people of the south to work? If the temperature variation of climate change was changing direction, on the warming side, it was now the north that needed trained manpower, and the south that needed adaptive innovations.

Climate justice has a double dimension: intergenerational and spatial. When protectionism damages social functioning in one generation, it bequeaths that damage to the next generation. Protectionism does not address the first dimension of climate justice, but neither does it address the second. The sea level rises for everyone; however, the consequences are not the same for the Norwegian fjord, the Bengal delta or the city of Jakarta. New opportunities are emerging in the far north due to global warming, which is very pronounced in the latitudes of Norway. This same climate change brings major irreversible impacts for the large river deltas. Submersion and salinization considerably reduce living and agricultural space in these low-lying coastal areas. Bengal’s main resource is its labor industry, which would be most affected by a return of protectionism and rising energy prices. Bangladesh would be the big loser on both sides of climate justice: both in the loss of most of its territory and in the destruction of its economy. In cold weather, the issue of climate justice is less pressing: in this case, the sea level is falling, increasing the available space in coastal areas. The problem of redistribution in cold weather then only concerns positive values: everyone wins, more (coastal polders) or less (rocky coasts).

Promoting green organizations and their freedom of establishment, setting up a budgeting system based on the evidence of mitigation and adaptation costs and climate change results, all these provisions have better properties than recourse to protectionism, which is nowadays the weapon of war used against the global normativity being constructed in the fight against climate change.

C.3.2. Excitement

One of the most important contributions among the ancient climate theories, belonging to Montesquieu, had already been constructed on the failure of the first mercantilist policies, Spanish and French, prefiguring those now put forward by the Trump administration. Monetary and budgetary disorders, permanent warfare dissipating all resources, persecution of people because of their religious practices, the slave trade – the great famines of the Little Ice Age formed the objective foundations, giving impetus to this program of ancient climate theory.

The use of charcoal was initially sporadic, often linked to episodes of extreme cold, before becoming widespread during the Industrial Revolution. This transformation reduced the harvesting pressure on European forests. The Industrial Revolution indicated that a democratization of enlightened mercantilism was not enough, and local interests captured parliamentary functions in the 19th Century and contributed to increased international instability and the spread of economic crises such as the 1929 crisis.

The theme of sustainable development was introduced at the time of the Brundtland Report, with the first climate models indicating a forecast of strong warming in the late 1980s. The environmental crises of the hole in the ozone layer and air pollution by acid rain were able to emerge relatively quickly, in a context of “big chimneys”, i.e. the negotiation was concentrated around a relatively small number of industrial producers responsible for the polluting emissions. In these environmental crises, economic instruments have proved to be effective: marine oil pollution has seen the development of a system of financial guarantee funds whose rules have made it possible to reduce the number and size of oil spills, and environmental taxation has made it possible to reduce air pollution. The principle of this taxation is that of a contribution requested from polluters, the rate of which increases with the volume of pollutants. It is not a tax system seeking to maximize the sums collected; the desired effect is the disappearance of pollution and thus ultimately of the quantity of tax collected. The 1990s, faced with the rise in delaying tactics by firms and states, saw the formulation of a precautionary principle, calling for action without delay, and relying on learning effects that can only exist because of this commitment.

The normative context on climate change is constantly evolving. However, the current framework established by the Paris Agreements in 2015 is dominated by a principle of voluntary commitment by States, organizations and individuals. The green finance system is complex, based on project analysis and supporting competition. The second major element of the normative context is the Sustainable Development Goals, a United Nations program for the period 2015–2030.

As a result of this principle of voluntary commitment, the efforts made are uneven and, on average, insufficient in intensity. The least advanced policies to combat climate change are those of a carbon club composed of countries with the common characteristics of having large land reserves and income from the sale of fossil fuels, relatively small populations, and high per capita carbon emissions (see Figure C.3). The Mediterranean and tropical biomes are negatively impacted, while the northernmost countries are expected to increase agricultural productivity. The balance is estimated for 2080 for the least committed countries in various ways, with Canada and Russia among the winners and Iran among the losers. A North/South opposition present in the forecasts of the consequences of climate change, with the South mainly bearing the costs of adaptation, is not found in the mapping of State efforts in the area of climate change. The map (see Figure C.3) brings together the most densely populated regions on the side of the larger commitments into two major areas, the heart of Asia with the two giants India and China, and a transatlantic grouping with its axis shifting south, associating Latin and Central America, Africa and Europe.

Figure C.3. Climate policy performance index 2019. Legend: red, least advanced policies; orange, not very dynamic policies; yellow, somewhat dynamic policies; green, most dynamic policies. No color: incomplete data. Source: Réseau Action Climat. Synthetic index based on the results of the year 2018. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/alaktif/climate.zip

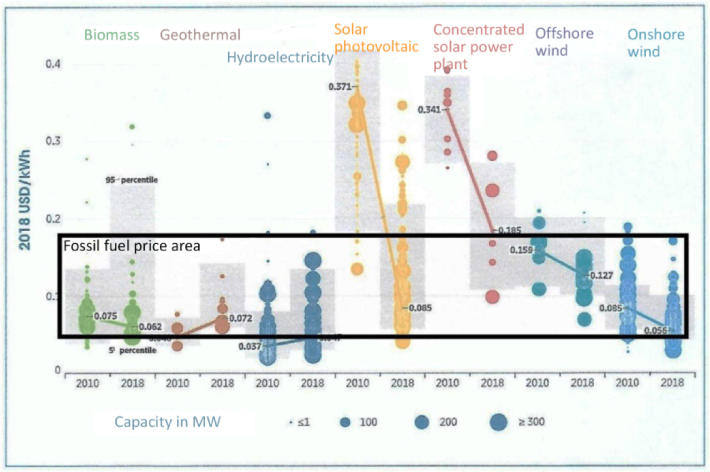

The evolution of the costs of sustainable and renewable energies saw a sharp drop during 2010–2018. Over the same period, fossil fuel prices and costs were volatile, with a fall in the price of coal, the most greenhouse gas-emitting energy, and high prices for hydrocarbons (see Figure C.4). In 2018, installed capacity in hydropower and onshore wind had the lowest overall cost. The increase in the size of the capacities installed in concentrated solar power plants made this sector competitive in terms of costs compared to fossil fuels.

Figure C.4. Overall cost of electricity in 2010–2018. Source: [IRE 19]. The size of the dots indicates the installed capacity according to the price and the gray rectangles the price dispersion. The line is a trend segment of the year-weighted averages of installed capacity around the world. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/alaktif/climate.zip

The framework set up by the Paris Agreements assumes that emulation will lead to an acceleration of the measures taken in the fight against climate change in order to maintain the average temperature growth set at 1.5 °C. For the very important area of energy transition, the available techniques for stopping the use of fossil fuels are not only mature, but also economically attractive. However, large-scale deployment needs to be accompanied by appropriate arrangements, which is being discussed by territories and activity sectors. Those who advocate only an environmental tax approach emphasize overall coherence in the fight against climate change [GOL 19]. Environmental taxes and subsidies can be understood from transition dynamics. Countries and cities that have opted for a strong temporary subsidy for the purchase of an electric vehicle have been able to create sufficient impetus for the large-scale deployment of urban transport decarbonization, which has now been achieved in Oslo and Shanghai. On the contrary, maritime and air transport, which benefit from the oil tax exemption regime, present the most situations of immobility, even though demonstrators of all types of “decarbonized” boats and aircraft have actually sailed or flown. The few copies marketed are intended for very high-end niche markets. An environmental policy for air and maritime transport must combine comprehensive environmental taxation with specific measures for the large-scale deployment of “decarbonized” capital goods.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) form the United Nations agenda for the period 2015–2030. Statistical indicators are used to monitor levels of achievement, particularly SDG 7 for energy transition (“7.1: By 2030, to ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services”; “7.2: By 2030, to increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix”; “7.3: By 2030, to double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency”). It is rather a favorable scenario for SDGs 7.1 and 7.3, to the detriment of SDG 7.2, i.e. energy mixes frozen in a technological conservatism, which is emerging on a global scale according to the latest report of the International Energy Agency [AIE 19]. The survival strategies of firms with strong market power that find themselves in competition with, for example, hydroelectricity in Central Africa, as well as the Trump administration policy are put forward as explanations for this poor performance. Sustainable and renewable energies are part of decentralized schemes, which hinder their dissemination, as major historical players in the energy sector can freeze the situation in their favor, while innovative energies remain confined to secondary achievements.

Climate theory was defined by Aristotle in a unifying persepective of the two parts of a dichotomy “without brutality”, at the time between Europeans with very unstable political regimes and a more stable East. The dichotomy at work today in the face of climate change is based on the capacity and speed of cultural adaptation. The map of this dichotomy is made up of large stripes based on variations in population density, as indicated by the analysis of the Yellow Vests movement in France [BUR 19]. The contrast is between generally sparsely populated areas, which use fossil fuels intensively and draw income, and very dense areas with multiple activities concentrated geographically. The question that a contemporary political art must ask itself is that of this same federative work taking into account this necessary territorial and organizational declination.