4

Networking Systems: Repeated but Hindered Initiatives

As soon as clusters begin to bring together more and more members, businesses or laboratories, their administrators think about ways to encourage synergies between them: seminars, workshops, calls for projects (for competitiveness clusters), afterworks, etc. Several formulas are tested so that entrepreneurs and researchers can meet and then develop collaborations. In the cluster studied, the networking system adopted follows much the same approach. It consists of bringing together workers from the site’s companies and laboratories around common themes or activities, outside working hours (lunch breaks are usually preferred) on a voluntary basis, and then waiting for spontaneous cooperation to emerge. In the example of Genopole, the system is deployed in three main ways: a policy of scientific administration through the organization of seminars and workshops, the pooling of equipment intended to be shared and the setting up of convivial and sporting activities.

4.1. Scientific and industrial administration: establishing a recurrent event

Although the scientific and industrial administration of the cluster has been a common theme throughout the history of the biocluster since its inception, it was only in 2012 that a real administration policy was implemented, including the recruitment of a person dedicated to its deployment.

4.1.1. The emergence of an intermediary figure: the cluster administrator

In 2011, a general meeting brought together the managements of accredited companies and laboratories to discuss the themes of “Company-Laboratory Collaboration”, “Biopark Administration” and “Site Life”. The names of these three workshops showed that the emphasis was on the cooperative aspect. To achieve this, it was necessary to “develop the scientific cluster into a real biocluster”1. The idea of transforming a biopark, with its geographical grouping of companies, research laboratories and training courses in the biotechnology sector, into a biocluster with individual and institutional relationships between these three players, is present in management literature (Hamdouch 2007). Up to this point, the issue of administration had been handled either by the Research Department, the Communication Department, or both. Although meetings had been set up, scientific administration had not been the subject of a policy on its own, but rather part of more general projects attached to other departments.

From 2012, the biocluster intended to entrust the development and implementation of an administration policy to a dedicated person within the Communication Department. Indeed, the management expected this position to define a strategic action plan for the administration of the biocluster, the objective of which being to develop meetings, interactions and collaborations between (1) the actors of the site and (2) with external partners, as well as (3) the attractiveness and visibility of the biocluster. Therefore, through this recruitment, the biocluster expressed its desire to develop an administration strategy. The role of a person in charge of animation was therefore part of the biocluster’s intention to systematize networking that had, until this point, been restricted mainly to the organization of scientific seminars.

Note that this type of position is not unique and can be found in other clusters in France: non-exhaustively, these include Silver Valley in Île-de-France2, the SPN cluster Professionnels du numérique dans le Poitou3 or even the Rhône-Alpes éco-énergies4 cluster. In order to respond to this professionalization, in 2014, the University of Strasbourg even delivered a Master 2 training course entitled “Cluster and Territorial Network Administrator”, the educational objective being:

To train cluster and trilingual territorial network administrators to develop innovative projects by creating synergies between businesses, universities, research centers and public administrations. This means: detecting the driving forces (public-private territorial actors), mobilizing them around projects based on individual needs and creating an administration and institutional cohesion unit for long-term action5.

A study of the courses offered online shows that this is the only training of its kind in France for the moment. Nevertheless, the very existence of training for such a specialized type of position testifies to the importance that these roles as intermediary between “companies, universities, research centers and public administrations” (see extract above) are likely to take on.

The job description circulated by the biocluster called for the establishment of internal “bridges” between the Enterprise department (Genopole Entreprises) and the Research and Platforms department (Genopole Recherche et Plateformes) at Genopole. In other words, the Animation Manager’s responsibility was to create the conditions for internal collaboration between independent departments serving different interests: laboratory support and scientific equipment development, on the one hand, and business development, on the other hand. Ultimately, the main task of this position was to bring together companies and laboratories at the biocluster level, based on the creation of a cross-functional project team combiningexecutives from Genopole Entreprises and Genopole Recherche. Since 2014, the team has been made up of two business managers and the head of business development at Genopole Entreprises, a project manager and the head of platforms at Genopole Recherche, and the director of Genopole Communication6. The person recruited for the position of Animation Manager embodies a combination of the two dimensions of public research and the business world. She holds a PhD in biology and has subsequently worked in marketing, notably in the pharmaceutical industry. This type of profile is also prevalent at Genopole Entreprises: several project managers originally had a scientific background, which they supplemented either with experience in the industrial sector or with a Master of Business Administration (MBA) in commerce, industrial property or finance. The Genopole Recherche et Plateformes project managers also have scientific backgrounds, including theses in biology. They have spent their careers in laboratories and then in scientific administration at institutes such as the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Institut National de la Santé Et de la Recherche Médicale), or the National Institute of Agronomic Research (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique), etc. As a result, the most notable feature of the Animation Manager and the Genopole Entreprises teams are their profiles of intermediation between science and industry. The Animation Manager works to create cooperation between researchers and industry, while the Genopole Entreprises team assists and advises researchers in business creation.

As a social intermediary, the Animation Manager organizes events that bring together staff from Genopole labs and companies: on the one hand, regular events, such as welcome sessions (WS) for newly accredited structures, themed workshops (around specific topics, such as intellectual property, patent law, etc.) and science and technology seminars; on the other hand, the formalization of working communities around a specific field of research and activity (immunology, synthetic biology, etc.) or common issues (such as management committees and PhD student clubs).

4.1.2. Networking and renewing acquaintances among cluster members through regular events

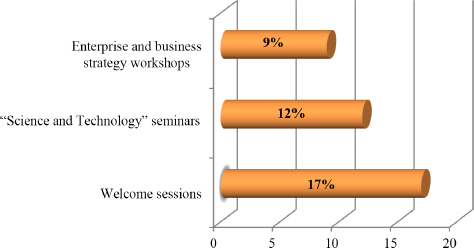

The WS, held around three times a year, involves welcoming companies that have recently been accredited. During a morning session, these companies present their activities to an audience composed mainly of executives or managers working in companies already established7. While the survey revealed a lack of awareness of the full range of activities, the WS were the events most spontaneously mentioned, whether in informal exchanges, interviews or data from the questionnaire (see Figure 4.1). The concept is appreciated and considered useful for getting to know new members, but difficulties in terms of time availability are often mentioned:

I use the administrative services when I can… The days where the companies present themselves, I found those very interesting. I went once, but after that I’ve rarely been able to go. It’s a great idea, but it’s a matter of availability afterwards… (interview with Blandine, director of an accredited laboratory, October 2015).

This availability is even more reduced during other events, such as workshops around a specific theme (patents, preparing clinical studies, recruitment) and science and technology seminars of a more academic nature. Like the WS, these events are more relevant to business and laboratory management, rather than to all employees: 12% participated in the seminars and 9% in the workshops (see Figure 4.1), whereas the questionnaire for managers shows that 40% of them participated. This difference in attendance between managers and their employees is expressed in the words of some respondents:

Yes, there are indeed workshops. I did one, but since then I haven’t been interested in any, because it’s more focused on managers with breakfasts, biz dev [business development], how to develop internationally, etc. […]. For me, there should be science-oriented themes, like some kind of congress, small conferences on a theme, each company doing a conference every week, and it rotating, so that everyone knows what the others are doing (interview with Leïla, director of studies at an accredited company, July 2015).

In 2016, there were 30 face-to-face events in total, equivalent to three events per month if we exclude the summer period, which is generally quieter. The number and frequency of events thus seek to create a recurrence of meetings between cluster members, so that they can initially meet and then recognize each other later.

Figure 4.1. Cluster workers’ participation in professional events

(source: graph constructed from questionnaire data sent to 102 people working in the cluster between February and April 2016). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/vallier/clusters.zip

On a regional and national scale, the biocluster organizes conferences open to outside audiences (industrialists, researchers, institutions, etc.) that are likely to develop into areas where interaction and socializing can take place. These events generally take place in a venue located on the AFM premises: the Génocentre. It is the “conference and convention center dedicated to science and business”8 and can accommodate up to 700 people. The biocluster generally organizes at least one conference at the Génocentre per year.

In terms of attendance, according to the questionnaire survey, 56% of managers interviewed and 27% of individuals of all statuses attended the conferences. The various observations and participations in these events suggest that they are more tools for promoting the site than vectors of cooperation. Two types of colloquia should be distinguished. First, scientific conferences: in particular, the International Innovation Conference in 20149, the Personalized Medicine Conference in 201510 and the Synthetic Biology Conference in 201611, which contributed to the cluster’s reputation at national and international levels. In addition, the conferences were more focused on the cluster’s accredited members, such as the Anniversary conferences, organized for the cluster’s 15th anniversary in January 2014 and for its 20th anniversary at the end of 2018, as well as the Genoforum conferences in 2011 and 2016. If we take the latter as an example, a preparation document stated the principle of the event:

As a showcase for Genopolitan know-how for the biocluster’s scientific and industrial community and the Ile-de-France region, Genoforum is an opportunity to reconcile science, business and conviviality via: a presentation of the strategy developed by the Genopole PIG within the biocluster’s perimeter, plus the opportunity to bring together the players who make the campus news (Genoforum preparatory note, February 5, 2016).

Indeed, while their formulation indicates moments of internal exchanges within the cluster (anniversary, forum), these events are seen as “showcases” that contribute to the reputation of the biocluster. Ultimately, this type of event, which is part of the cluster’s administrative policy, seems to be more of a tool for promoting the site than an opportunity to highlight and encourage synergies.

4.1.3. Fostering communities of practice: the creation of thematic bodies

In addition to this protean event strategy, Genopole aims to encourage formal and informal groups of individuals with common interests or research themes. Three mechanisms were observed during the survey which demonstrated the application of this principle: a management committee, an immunology theme group and a PhD students’ club. In this logic, the sharing of an interest or a common problem would lead the actors to build together a shared understanding of the activity. The constitution of these groups echoes the theories developed in knowledge management around the concept of “community of practice”, which is defined as:

A group of individuals who share an interest, set of problems, or passion for a topic and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in that area through ongoing interaction (Habhab-Rave 2010, p. 45).

Wenger distinguishes the community from the group, team or network (Wenger 2005), asserting that what defines community is mutual commitment; it is not simply a set of individuals with common characteristics (ibid. p. 83). This is, however, the bias of the biocluster: to bring together individuals with common characteristics, whether in terms of their status (in this case, managers or PhD students) or their research theme. However, mutual commitment is not based on shared attributes, but on the practice of the individuals in the community. From this point of view, the biocluster’s science and enterprise steering committee (Comité d’Orientation Science et Entreprise du Biocluster, COSEB), that is, the cluster’s management committee, is having difficulty forming. One of its members explains these difficulties, one year after its creation in 2013:

The objective of COSEB is to achieve fruitful exchanges between researchers but also between entrepreneurs, that’s what really characterizes COSEB. We try to find a balance between public and private laboratories and entrepreneurs and we try to exchange. So, as the COSEB president would say, “we’ve already got to meet and talk to each other, to speak the same language”, which is no mean feat… But it’s been through regular meetings, about every two months, that we’ve been able to discuss the problems and needs that we have at Genopole. We’ve tried to create small events, tried to do concrete things, so it’s pretty trivial, but to make sure […] that there is a kind of synergy that is a little stronger and that things really emerge from the fact that we are all grouped together in the same location. So it’s in line with the objectives of the PIG, but we have our independence. We try to help them to see how to improve things, because it really is based on the concrete, on the fact of being the most consecutive. The risks, however, are that actors don’t completely see the interest, because we don’t really do concrete things that bring something to the entrepreneurs, and we are neglected because of a lack of interest. This is the major risk (interview with Emmanuel, laboratory teacher-researcher and platform manager, July 2014).

In this interview extract, we understand that the more the group meets, the more it creates a common language and a form of mutual trust that leads everyone to express their needs and problems. Nevertheless, while the literature generally concludes that the emergence of a common language and trust between actors leads to strategic exchanges (Estades et al. 1996; Galison 1997), we note here that this concretization struggles to emerge.

In 2015, two years after the creation of COSEB, a new modality was tested using “thematic clusters”. The idea was still to bring together researchers and industrialists in working groups, but unlike COSEB, where all accredited members were invited, here the idea was to bring them together according to their field of research and activity. The management of the biocluster saw all of its members as “links” that needed to be connected: firstly through training, then research and finally industrial and clinical applications. Nevertheless, these links did not belong to the same value chain, hence the idea of grouping them by theme. The literature on communities of practice emphasizes the need for a common theme, so that different stakeholders understand each other well. They would then be characterized by a shared language or a common subjective view of the world developed through their common experience (Brown and Cook 1999). A similar philosophy was at work with the creation of the first thematic cluster on immunology. However, the needs identified by the group in question did not appear to correspond to the biocluster management’s instruction to create partnerships. Indeed, for the members, the two priority objectives were, firstly, to get to know each other better and, secondly, to bring immunology specialists to the Paris Region for conferences on the latest advances or technologies in the field. One of the members of the thematic group on immunology explains how it worked and the different choices they made:

The idea was that, since the labs’ activities may be quite different, we said, “Let’s try to make thematic groups”. So we made a Genopole immunocluster group to interest immunologists in the broadest sense of the term, both from an academic and biotech point of view; so we formed a small committee that mixed biotechs and academic labs. We made a first presentation, there were 20, 25 people on therapeutic antibodies, the next one will be me presenting, so we’ll see how it goes… The other idea was to set up a LinkedIn group to share news on the world of immuno, or on everything related to the use of antibodies, or other things. Everyone can contribute to it, but […] they don’t really use this service (interview with Alexandre, director of an SME that left the cluster in 2016, September 2015).

Once again, we can see that the partnership dimension is not the priority of the actors involved. They seem to be more concerned with exchanges of information and advice or the support of scientific experts from outside the cluster than with the integration of their respective structures into a value chain.

Finally, the last group observed is part of a strategy to bring together PhD students and postgraduate fellows from the different laboratories of the biocluster. Unlike COSEB and the thematic clusters, which were simply observed, the analysis of this last group is the result of the observation of a participant, both as a salaried PhD student of the biocluster and as a member of the project team supervised by the Animation Manager, who considers that PhD students are a pool of potential future entrepreneurs, likely to settle on the site in the long-term. It seems to her that it would be better to rely on the potential of PhD students, who are already on the site, for the creation of companies, rather than to bring in companies or young entrepreneurs from outside the site. In her opinion, we should base our approach on that of Minatech12 and the Doctoral principle, which aims to organize meetings between PhD students and businesses. These meetings may take the form of presentations of work to industrialists, teams of PhD students responding to a company’s problems over a given period of time, or even regular meetings between students and recruiters. This approach is seen as a way to mobilize PhD students in a fun way, while helping them formalize their scientific work in a way that is understandable to potential investors or employers.

Thus, the first “ApéroDoc” organized on the cluster brought together about 30 PhD students over a drink, divided into several groups, who had to introduce themselves to each other, and then discuss the actions to be implemented. Throughout this event, the Animation Manager highlighted collaboration projects between them or with companies, or the creation of companies based on their work. The second event, organized six months later, was only attended by four people. Nevertheless, the group got its second wind a few months later thanks to the involvement of a postgraduate student from the site, who started to organize “post-thesis” meetings. The first two of these were on the theme of “What market for PhD employment in France?” led by a consultant from the Health division of the recruitment firm Michael Page, and “Applying for a job after your thesis or post-doc”, led by a recruitment officer from Kelly Scientifique13. This theme was then eagerly exploited by the PhD student group, who then organized a series of conferences aimed at drawing up portraits of former PhD students on the theme “They defended their thesis, what did they become?” These meetings became an opportunity to shed light on the jobs available to postgraduates.

There is a consistent theme running through the three examples of thematic group formation described above (COSEB, the immunology cluster and the PhD students’ club), in that they were all initiated by Genopole and created from scratch as part of its administrative policy. This involvement has consequences in terms of the expectations set out by Genopole, whether that means taking part in the overall strategy of the biocluster and setting up partnerships for COSEB and the thematic clusters, or engaging in business creation for PhD students. In the end, however, the actors involved in the three experiments developed common themes and interests outside the scope of the cooperation between science and industry desired by the cluster. In fact, they were unanimously more interested in the creation of groups from which they could seek advice and information, whether they were managers, seeking to develop a network based on trust, researchers and industrialists specializing in immunology, wanting to join together in the search for information from other specialists in the field, or PhD students, looking for answers to a common concern about their professional opportunities.

4.2. Sharing a technology platform: mutualization or collaboration?

One of the particularities of clusters is the pooling of resources that could otherwise not be paid for by a single company or laboratory. These shared spaces, beyond their instrumental function, are also considered as places conducive to the development of common projects.

4.2.1. Resources as an intermediary: a policy of sharing expensive equipment

Based on the literature, clusters can be said to be an intermediation structure. In this sense, intermediation must be understood as a means of compensating for the imperfect circulation of information between suppliers and customers and facilitating contact between two worlds (businesses and laboratories) with heterogeneous knowledge and action logics. The structure would thus be organized on a continuum of action whose two ends are “network” and “actor” intermediation (Branciard 2002). The objective of network intermediation would be the dissemination of information, potential partnerships, obtaining financial aid, etc., while actor intermediation is involved with backing technological and scientific development projects. The cluster, for its part, implements a policy of shared equipment which, in line with this analysis, constitutes a third path that can be described as “resource” intermediation. Thanks to its financial backers, in particular the Regional Council and the Department, the structure effectively offers equipment, mainly installed in laboratories that would not have been able to finance it themselves. In total, the biocluster has 19 shared platforms and a technical platform. For the life sciences, this requirement is based on the use of instrumentation and new information technologies to generate, store, analyze and represent vast quantities of data.

These platforms come in various forms: animal houses and imaging facilities for producing and analyzing transgenic animals, DNA sequencing equipment, advanced genetic methodologies for pathologies, DNA encapsulation, etc. Thus, they form a set of resources available within the perimeter of the cluster. Historically, however, the majority of platforms in France were built around instruments within universities, university hospitals and laboratories attached to public research organizations (INSERM, CEA, INRA, CNRS), in order to develop internal research programs (Mangematin and Peerbaye 2004, p. 705). These platforms then opened up to other users from other laboratories, then from companies or industrial laboratories, thereby creating new markets. Although the biocluster platforms were created for the Genopolitan community, some are more widely used, including commercially, and are the result of initiatives led by research organizations.

Accordingly, the legal mode of execution, the fee schedule and the terms of access are defined by each host structure. That said, the principle of granting preferential rates to French public laboratories seems to be a rule shared by most platforms. This is notably the case for a bioinformatics platform. With its “France Génomique” accreditation, it has benefited from an “investment for the future” to keep France at the forefront of genomic data production and analysis. Its services, therefore, have a national scope. Thus, in order to guarantee quality access, some platforms are developing systems that allow remote use, making geographical proximity incidental. This is particularly the case for the bioinformatics platform, which allows remote work on genomes, whether or not they have already been made public:

It is a software environment […] with a certain number of public genomes, there are less than half, about 40% today. These genomes are accessible, there is no need to “log inˮ, we are in “guestˮ mode. [And with private genomes] when people submit their genomes to us, what they want is for us to do the annotation, There is a coordinator. We interact with one person, that person then manages it. He has a user-friendly interface available and he can then create accounts for all his collaborators wherever they are in the world, to produce analysis and expert annotation (interview with Edith, laboratory CNRS research director, February 2017).

Apart from an optional four-day training course in the bioinformatics laboratory that teaches the prerequisites for using the platform, users can enjoy the platform independently, without physically being in the same place. Consequently, the platform is even able to offer services on an international scale, as shown in the extract above.

Other platforms, on the other hand, have a much more local focus. Although they are theoretically open to all users, they are essentially aimed at the members of the laboratory to which they belong. For example, let us listen to a platform manager, who explains that, ultimately, the majority of users are either directly in the laboratory, or in the start-ups created from the laboratory’s research:

We have many academic researchers in the laboratory who use the platform. And we have an activity that is really on the rise, these are the start-ups that we have aggregated around the laboratory, which are ultimately spin-offs of the laboratories, of the technos [technologies] that were developed in the research teams […] There is, for example, a company that was created and that uses the platform a lot and two other companies that are in the process of being set up and that also use the platform, so that is the biggest use. Then we have partners outside the laboratory, but who are more marginal. We have an academic partner who uses the computing resource, and then, I don’t have the details, but we have three or four companies that come on an occasional or regular basis. However, it’s very, if you will, light compared to the platform’s overall activity (interview with Gwenaël, laboratory research engineer, February 2017).

In this case, the platform is truly at the heart of a strategy of the laboratory and its spin-offs, which all use the same technology, and in the end, it is of little use to the rest of the biocluster’s users. If we take a closer look at the use of the platforms by the 102 people who took the questionnaire, we find that seven platforms have never been used by the panel.

On the other hand, some are used more than others, such as the animal house and the imaging and technical platforms. The latter, which is found in the business incubator, differs from the platforms in that it offers only technical resources, whereas the platform offers, in addition to its equipment, skills through the personnel made available. The animal house and the imaging-cytometry platform are essential facilities in the field of life sciences. In addition, their presence has been mentioned, in many informal and informal discussions, as a factor in attracting new companies, as the biocluster’s management explains:

At the start, we only saw resources for better working in the instruments we bought. Then, afterwards, we had this very political vision that a good platform, like a good pet shop, can be an attractor of companies and an element of conviviality, exchanges, etc. (interview with biocluster management, April 2017).

In this extract, we note a logic change regarding the platforms, from a positive tool for accredited members to an instrument of attractiveness and exchange. When a director of studies of an accredited company located in the incubator is asked about the reasons for the company’s location, she explains that the animal house is the main factor:

I think it was financially because they looked to locate in Pasteur, in several places, but it was mostly related to the animal house, because it’s a very nice animal house and for the company it was paramount because it’s our main activity, we don’t have a place without an animal house, we use it daily (interview with Leïla, accredited company director of studies, July 2015).

Thus, this attractive dimension joins the observation of a pragmatic need on the part of the cluster members, who see the use of the platforms primarily as an advantageous service that they can access, which prevails over collaboration opportunities.

4.2.2. Platform usage: service provision before collaboration

The platforms offer two different types of usage of their equipment. They offer: (1) service or development activities in support of research laboratories or their spin-offs; (2) they also develop collaboration activities, the results of which are embodied either in coauthored publications or in joint patents:

The framework contracts are designed to ensure that the benefits from the results are shared. In concrete terms, for the researcher, this means that he or she will be a coauthor of a publication because there is a minimum investment in time, as well as in the use of equipment, so, yes, this can lead to academics being published. Then, in theory, it can lead to joint patents (interview with Emmanuel, laboratory teacher-researcher and platform manager, February 2017).

These uses echo the typology drawn up by Hatchuel, Le Masson and Nakhla, who distinguish between two main devices (Hatchuel et al. 2004). The first is the shared analytical device (Dispositif d’Analyse Partagé, DAP), which they describe as a set of rather routine activities: the protocols are already finalized and well known and have a scientific research operation function. They are part of a service provision logic. The second is the shared experimentation device (Dispositif d’Expérimentation Partagé, DEP) which, as its name indicates, is centered around experimental and collaborative work. In this case, the research protocol needs to be designed with a high degree of cognitive and geographic proximity to meet the evolving needs of the research object. These two models (service and collaboration) reflect two poles of activity, one oriented towards the commercialization of the knowledge production system, the other towards coproduction and scientific cooperation. The DAP system would then consist of an instrumental link in the subcontracting of R&D. Producing little innovation by itself, a DAP platform is thus distinguished more by its quality service activity with a global network of clients. The main risk it faces is the rapid standardization of the platform in the face of increased competition from more innovative platforms, whether public or private (Aggeri et al. 2007a, p. 31).

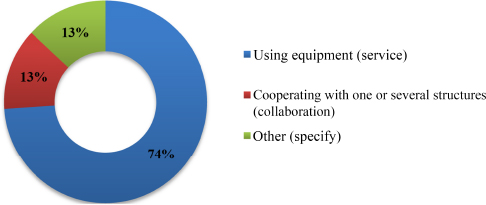

In 2017, on the biocluster, there are four collaborative platforms, whose utilization is conditional on the development of a joint scientific program, and six service platforms that do not require scientific collaboration. In addition, there are eight mixed platforms that offer both service and collaboration. As we have seen, the technical services of the incubator differ from the rest of the platforms in that it does not offer the provision of specific skills, but rather provides the incubator tenants with access to all of the shared facilities (central laundry, freezer room, sample preparation room, etc.). The dominant use of the platforms seems to be equipment usage in a service rather than cooperative sense. Of the 102 people who took the questionnaire, only 22% answered positively to the question “Have you ever used one or more of the shared platforms?” Half of these were PhDs and the other half engineering postgraduates, PhD students and R&D management positions. 55% answered “no” and 23% said they did not know about the existence of platforms.

Figure 4.2. Type of platform usage by users

(source: graph constructed from questionnaire data sent to 102 people working in the cluster between February and April 2016). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/vallier/clusters.zip

In 74% of cases, the panel’s users only used the equipment for service provision, in 13% of cases to cooperate with one or more organizations and the remaining 13% who checked the “Other” box all specified that they used it because the equipment was located in their laboratory. From the management perspective, 44% said that their organization made no use of the platforms and 3% did not know what they were. All of the managers who said their facility did not use platforms said that they had no use for any of the equipment offered. Of the 53% who said they did use them, 11 were company directors and 6 were laboratory directors. Fourteen said they used the equipment as a service, only two used it in collaboration and one because it was in their laboratory. In the end, both the quantitative and qualitative surveys showed that the activity is more about service than collaboration. The following statements clearly illustrate this logic:

I met with the platforms manager at Genopole, at one point, because I was responsible for an L3 laboratory and we wanted to potentially open it up to the outside world if people needed an activity […] and we have people from many companies who come here, so it’s working quite well […]. But no, it doesn’t allow us to meet each other, but it provides a service, because we don’t even see the people, they come at their time slot, analyze their data and leave, because it saves them from developing a platform that costs an arm and a leg. We have a microscope in imaging that costs 200,000 or 300,000 euro (interview with Fabrice, accredited R&D laboratory researcher).

From this point of view, Genopole appears to be a special case in terms of the way in which the sociology of science tends to identify shared platforms: as a specific trading zone, that is, a zone of exchange between different cultural and disciplinary groups (Galison 1997; Shinn 2007). In France, Vincent Simoulin, in particular, shows the emergence of an interstitial community linked to the diversity of actors around a scientific facility – the first third-generation synchrotron – while highlighting the specificities of this heterogeneous collective (Simoulin 2012). In the case of the biocluster, on the other hand, work on the platform is more compartmentalized than interstitial, as the interview extract above shows. Occasional access to expensive, high-quality equipment is preferred, leading to sessions of usage that do not then allow for sufficient decompartmentalization between research teams or companies in the cluster.

4.2.3. Equipment demonstrations: connecting or making visible?

Since 2013, the biocluster has been organizing Journée des plateformes (Platforms Day), better known by the acronym “JPF”, in the meeting rooms and corridors of Genopole. These days are presented as an opportunity for biocluster members to discover the diversity of the offer and to exchange around needs, partnerships, collaborations, services, etc. These events are part of the action plan implemented by the Animation Manager and the Genopole Recherche Platforms Manager. The aim is to publicize the platform system to accredited members and to extend it to companies and laboratories in the Paris region, which are potential clients. The stated objective is to create a dialogue between the public and private sectors on different topics in order to decompartmentalize research. Each day’s program generally consists of a presentation of certain platforms, with priority given to new ones where appropriate. Round tables are also organized on issues specific to the platforms: data security, contractualization aspects, etc. Of the laboratory or company managers who took part in the survey, 56% said they had already participated in the Platforms day, but only 9% had developed cooperative ventures from them. This data is consistent with the testimonies of several platform managers who explained that they had not developed any collaboration during these events:

We haven’t, no, because the themes are really different. Well yes, I’m saying that, but, indeed, I did meet some people who I had never spoken to. However, in terms of the activity of the platform, the JPF does not bring us much, but it is very good that it is there on the site and it is a time when we can see each other. But if we look at the indicators, or in a quantitative way, it has very little impact on our activity (interview with Gwenaël, laboratory research engineer, February 2017).

The above extract reflects a divergence of themes among the participants that is too broad for generating common interests. At best, opportunities may present themselves, but not materialize. Indeed, there are many accounts of “near-relationship” cases, as the following extract indicates:

So we participated in all these days and, once, we almost created links. Moreover, it would have been great, with L’Oréal, so someone who came to participate in the days but outside the cluster […]. But we didn’t hear from them, it’s true that the person we met was extremely interested, but I guess she didn’t manage to pass on the message to her managers afterwards. So it’s been all downhill from there and, after that, I haven’t wanted to chase after industrialists, if they are interested, we talk, but that’s it… (interview with Edith, laboratory CNRS research director , February 2017).

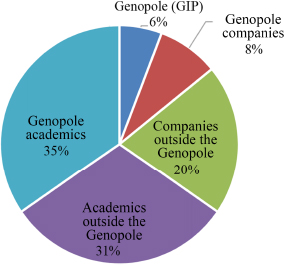

This potential collaboration with L’Oréal, which could not be realized, led to a closer analysis of the list of 156 participants at the 2016 Platform Day, in order to identify their institutional affiliation. It emerged that 50% of the participants were industrialists or academics from outside the cluster. Of the other half, 35% worked in the laboratories, 8% in companies on the site and 6% in Genopole.

This attraction of actors from outside the cluster for the Platforms day can be explained by the presentation of equipment by recognized equipment manufacturers. In fact, they were the sponsors of the day; in exchange for their financial contribution, they were able to come and present their instruments, or even give demonstrations during the Platforms day or during dedicated “equipment demo“ sessions. The aim of these events was to promote the use of existing platforms through specific workshops or equipment presentations, as well as to bring in instrument demonstrators for future investments. These “demos” are a term commonly used by a multiplicity of actors, including researchers, engineers and computer consultants, to refer to a presentation of a technological device in action, such as software or a robot (Rosental 2017, p. 75). These demos are widely used in Silicon Valley, not only to promote science and technology, but also because they serve to connect multiple actors whose likelihood of coming into contact would otherwise remain low.

Figure 4.3. Institutional affiliation of the 2016 Platform Day participants

(source: graph constructed from the attendance sheet of the 156 participants attendance sheet of the 156 participants of Platform Day on June 23, 2016). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/vallier/clusters.zip

On this point, however, as with shared platforms (see section 4.2.2), the biocluster tends to stand out. Rosental, in his survey of the California cluster (Rosental 2017), sees demos as sales tools, forms of self-promotion and interaction. He explains that the “demo” becomes a kind of calling card after a first contact and that thus the spectators are, with time, likely to become project partners, if not users, sponsors or customers of the prototypes or future products presented (ibid., p. 76). From then on, the demos turn out to be operators of networking that replace other forms of social relations between scientists, such as meetings, informal encounters, café visits, etc. (Ravelli 2007). They also empower the demonstrators to develop an experimental approach by observing the reactions of the audience around the objective that the equipment represents (what may or may not be relevant, what needs to be improved, etc.), which makes it possible to “define a common identity and the nature of the relationships between the protagonists” (Rosental 2007, p. 152). This networking function of the demos, as highlighted in the literature, contradicts the results of the questionnaire, where only 14% of individuals interviewed had ever previously participated in one of the demos on the site, none of which had otherwise resulted in collaboration. The following interview extract makes this clear:

When they bring in equipment manufacturers, people who present new technologies, not many people come. And yes, you can come and see this machine, but in any case we are in companies that cannot afford to buy it and we know that Genopole will not pay for it. So, yes, there have been some, but the machines financed by Genopole are supposed to be pooled, so that they can be used by the companies that have requested them. They say you can come and use them, but in the end you have to come at certain times, within a strict timetable […]. If you look at the machines bought by Genopole, it’s the big companies, they’re on their side, and that, here, is a shared feeling and, basically, a feeling of injustice. If we’re at X, yes, we have; if we’re at the incubator, not so much (interview with Françoise, research engineer in a company located at the incubator, July 2015).

Here, instead of encouraging exchanges, the equipment creates a kind of rivalry between those who can see their structure benefitting from the installation of a shared platform and those who cannot. This feeling of injustice is reinforced by the essential function of this equipment for companies and laboratories. Indeed, the rivalry that these demos bring to light shows the strong presence of fixed capital (instrumentation, platform) in science, without which science cannot exist. Therefore, the demos highlight the visibility and unequal access of the structuring dimension of this fixed capital.

While demos and platforms appear in the literature as potential vectors of cooperation, it is difficult to establish relationships here. The platforms seem rather to be reflective of a policy of making equipment available (in order to ensure the proper development of the site’s laboratories and companies) and a perspective of attractiveness. In addition to the support offered, accreditation can be seen as a means of accessing state-of-the-art infrastructure for laboratories and companies.

In this context, networking seems to take a back seat, as the accredited members focus on service use in order to develop their respective activities and not their partnerships. In the context of scientific experimentation that the platforms represent, exchange appears limited. On the other hand, the analysis of knowledge transfer practices also reveals the role of informal exchange spaces (Lamy and Le Roux 2017, p. 109). These spaces are also favored by the biocluster and are part of its palette of tools for establishing relationships, which are conceived in terms of conviviality.

4.3. The institutionalization of conviviality: “la vie de site”

The idea of a cafeteria effect was born at the same time as the first technopoles. It is based on the principle that it is during an informal discussion around the coffee machine or in a convivial setting that links are forged and lead to professional collaborations.

4.3.1. Bringing together and involving employees from different backgrounds

Since 2010, the cluster under study has been strongly implementing a final dimension for better cooperation, which involves a social and convivial policy around sports and cultural activities. The principle behind this policy is the idea that informal and playful networking can lead to professional relationships. This policy is known as “site life”. It refers to cultural and sports activities, as well as infrastructure such as the creation of day care centers or cafeterias. In 2013, the biocluster made this a key focus of its development:

Administration and site life have been identified as major aspects of the “Genopole 2020-2025ˮ strategic plan. The main objective is to make the Genopole biopark a biocluster defined by the values Work, Live, Interact and Play: Work: a place where it is good to work; Live: a pleasant working environment; Interact, Play: providing employees with leisure, cultural and sports activities, etc. (2014 biocluster activity program, section IV. Site Life).

In 2012, Genopole wanted to develop a coherent and integrated strategy for the various user-friendly initiatives developed on the site. To this end, it subsidized a successful local initiative that has accompanied Genopole since its creation. This is a newspaper called Forum, created by an employee of the Genomics Institute, which mainly reports on social events such as farewell parties, births and birthdays, as well as on laboratory life (discoveries, technologies, arrivals of researchers, etc.). Created in 1999, this journal was first written by this one employee, then gradually gathered other contributors. For nearly 13 years, this journal was published “by hand” (printed and bound with staples). In 2012, the biocluster committed to financing a more formal edition and recruited its editor-in-chief, provided by his employer.

Forum fulfills the functions of a company newspaper concerning the “family spirit” (Saint-Georges 1993, p. 10) that it disseminates to its readers, using the terms “we” or the “Genopolitans”. Above all, it disseminates news from the various entities of the cluster under the same banner, whether they are of a convivial or professional nature. This aggregation within the Forum newspaper is indicative of the general strategy of “Site life”. Indeed, the editor-in-chief of the newspaper is also the “Site life” project manager within Genopole and, when taking up his post, his mission was to deploy an overall approach based on already existing initiatives. There are several formal and informal association initiatives in the biocluster. These include the Genopole workers cultural association (Association Culturelle des Travailleurs de la Genopole, ACTG), which has been operating within the Genomics Institute since 2003 and offers activities as diverse as language courses, guitar lessons, dancing, etc. We can also mention the Association Le Téléthon des Chercheurs, created in 2006, which essentially brings together people from the AFM-Généthon-I-Stem sphere, and which organizes various activities around the collection of donations for the Telethon and runs the Évry Telethon Village. It should be noted, once again, that these initiatives depend on the two structuring actors of the site: the AFM and the Genomics Institute. Alongside them, Genopole has also set up a number of initiatives, notably the “Gen’envie” platform14, which organizes a series of events: an annual picnic in the communal gardens, popularization courses, etc.

Faced with this diversified but fragmented offer, the need for overall coherence on the campus as well as employee involvement became decisive. This convivial dimension was piloted by a project team (composed of Genopole’s structure employees) which proposed an action plan and objectives. The aim was to create an association of employees who would take charge of cultural and sports activities, by getting the employees involved so that they would take ownership of the project. The action plan was inspired by a series of methods, themselves inspired by participative management. Although the literature observes the “lack of clarity in the definition” of this management (Borzèix and Linhart 1988, p. 38), the main device remains the work group in which employees are mobilized around a particular issue or problem. First of all, the project team, having committed itself to providing a multi-purpose room, set about gathering the expectations of the employees concerning the activities they wanted. A questionnaire, with the unifying slogan “Deciding together changes everything”, was distributed to all the member establishments of the site. More than 500 people responded to this questionnaire, which ended with an invitation to those interested to take part in workshops, with the title “General conditions of site life”, and to leave their contact details. The results of this consultation were then used as a basis for these workshops, which took place a few weeks later. The ideas developed during the workshops were presented in a document, but were not really implemented. Effectively, the working groups were composed of biocluster employees, but with different backgrounds; thus, their participation in an artificially formed group, outside of the work group to which they belonged, strongly constrained their involvement. These resistances can be found in Borzèix and Linhart’s definition of participative management:

The new participatory formulas depart from this natural and private universe. They are organized, initiated and monitored from the outside by the management, on its initiative and under its control. They are artificial (because of the places where they are held, in meeting rooms, outside the workshop); they are foreign to the customs of productive work […]; they are specific or even exceptional […]; finally, and above all, they do not follow […] either the contours or the functions of natural work communities […]. Extracted from their group membership, the individuals who participate in them are confronted with logics coming from elsewhere, with new interlocutors: workshops or neighboring offices, functional or administrative services […] they are invited to abandon their original solidarities and their partisan alliances to leave their confinement and their particularism. They are encouraged to become aware of their belonging to a whole (ibid., pp. 49–50).

This particularism, which was mentioned above, is all the more reinforced in the case of these “General conditions”, insofar as the participants do not have the same employers. Thus, in addition to this extirpation of the original belonging, it is very difficult individually to be committed in the workplace to a project that is not that of one’s employer, all the more so when this project concerns non-professional activities.

4.3.2. Building emotional and community connections through volunteering and sport

The actual involvement of employees in the implementation of the conviviality policy was quickly abandoned in favor of direct responsibility by the project team. On the other hand, the participation of employees was decisive in encouraging them to “become aware of their belonging to a group” (Borzèix and Linhart 1988, p. 50). They were therefore invited to take part in symbolic actions that allowed the development of a common identity for this heterogeneous group. Indeed, following the working groups, a new questionnaire consulted employees on the name they wished to give to the future multipurpose hall. Proposals were suggested electronically and then a vote was held to elect the winning proposal. At first, this type of device emphasized a predominant affective dimension in group relations (Sainsaulieu 1985, 1977 and 1988). Indeed, a recreational moment like this temporarily minimizes the importance of professional group memberships. Then, the principle of the vote granted a democratic spirit to the construction of the project. Reciprocally, this democratic gesture also participated in creating an affective link between employees, who decided on the name, even if not unanimously, and the multipurpose room project. The name finally chosen, L’Escale, reinforced the recreational character of the place at the same time as it associated an idea of space outside professional time. This construction of identity was a feature of managerial practices known as “governance by culture” (Crozier 1991, p. 51), or “cultural management”, which consists of conceiving a corporate culture composed of values, norms, rituals, myths, etc. The constitution of a community requires a sense of belonging, in which the individual’s institutional support is sought:

In a community issue, consent is no longer only contractual, but also, and above all, affective. Moreover, the feeling of belonging must be so strong that the link that unites the employee to his company must be more an affective and moral link than a contractual one (Barbusse 2008, p. 409).

Thus, the feeling of belonging to a collective – this is the word used by the project team in its communication: “a collective of biocluster employees”, initiated during the working groups and then confirmed with the choice of the room’s name, is accentuated throughout the project. Indeed, meetings are organized quite frequently, about every three months, before and since the opening of the room, in order to keep the employees involved informed about the progress of work and the organization of activities. Following a call for applications, some employees from the site volunteered to run a workshop at L’Escale. When the hall opened, “open days” were organized with booths run by the volunteer organizers: knitting workshops, fitness, dance and relaxation classes, groups of soccer players and an athletics club. Registration for sports activities was the most successful, but posed problems in terms of insurance, which prompted the collective to become an association under 1901 legislation. Thus, the Escale des Genopolitains association was created at the beginning of 2016, one year after the start of activities in the hall. A membership system was set up and very quickly the number of members passed 250. In addition to the workshops, festive and convivial gatherings (afterworks, picnics, etc.) and events (Easter chocolate sales, clothing exchanges, Christmas markets, etc.) have been added. Overall, the desire to involve employees outside of their professional duties is mainly through sports mobilization, since “when we know the unifying and identifying capacity of sports, we understand why companies that want to unite their employees around common values turn to sports” (ibid., p. 409). This ambition is part of a double movement. On the one hand, personalities of the wellness movement are inspiring the emergence of employees eager to start their day with a jog or a fitness session (Cederström and Spicer 2016). On the other hand, the directives in vogue around well-being at work prescribe the installation of table soccer, rest rooms or the organization of afterworks, etc.

4.3.3. L’Escale, a space of sociability revealing professional hierarchies

Creating the conditions for conviviality is an old idea, the beginnings of which can be seen in the discourse surrounding the emblematic technopole, represented by Sophia Antipolis in the innovation imaginary in France. Pierre Laffite, its director, explained the need for the Sophia Antipolis Foundation to maintain conviviality on the site in parallel with more professional events:

We also need more convivial and confidential meeting places so that scientists and businessmen feel they have a home of their own where they can meet for a debate, dinner or show and do business. It is necessary that the baker can meet the financier and the chemist can meet the engineer, that is cross-fertilization […]. Other meetings take place during lunches, exhibitions or concerts. It is interesting that a music lover from Digital Equipment can meet a music lover from the Ecole des Mines at a Mozart quintet concert, because they can then develop other relationships (“Les leçons de Monsieur Technopole”, Meridian interview, 1988, p. 37).

In the same sense, L’Escale is envisioned as a place where individuals can meet by chance, during a sports or cultural activity. The questionnaire survey reveals that the hall was frequented at least once, in 2016, by 45% of the 102 individuals interviewed, making it the most used sociability space at the time of the survey. The literature on this type of space emphasizes its importance as an institution of socialization. The expression is used to describe the places where the French community in Silicon Valley socializes, such as the French school in Palo Alto, the film club, French restaurants, July 14th celebrations or the Beaujolais Nouveau Day (Dibiaggio and Ferrary 2003). From this point of view, this community developed behaviors specific to any expatriate ethnicity, by reproducing the characteristics of French culture and practicing its mother tongue (Portes 1995). Although the ethnic character is not appropriate in the analysis of L’Escale, it participates, like the French community, in the construction of non-economic social ties through communal activities. Nevertheless, in the case of L’Escale, it is difficult to speak of socialization, because it is not a matter of individuals internalizing or sharing a value system. It is more appropriate to refer to it in terms of a space for sociability. Indeed, its success has been explained, on several occasions, by the activities proposed and by the fact that it represents one of the rare places of sociability:

L’Escale, clearly L’Escale. So it’s all new, I tried Shiatsu, stretching and fitness […]. There are people I know from here (the nursery) and we meet at L’Escale and we talk more easily. Afterwards, I’m a fairly sociable person, so I don’t mind sitting at the table and talking. I know some people from the company who will go to L’Escale, but who will stay in their own little group and, outside of L’Escale, there’s not much socialization (interview with Leïla, accredited company director of studies, July 2015).

The point raised in this extract, the formation of groups on a professional basis during convivial events, came up several times during the survey. Indeed, although they are away from their workplace, whether at L’Escale or at picnics, employees tend to recreate groups based on their professional affiliation:

I only came to one presentation where investors were there, my manager went more often. Me, I went more to the lunchtime events, there was a picnic, there were a few tips… The second time, I went with the idea of getting to know people and, again, it’s not easy because people know each other and stay in their own companies (interview with Rizlaine, accredited company biomechanics engineer, December 2014).

This biomechanics engineer, the only employee in her company besides her manager, was keen to meet people over lunch, but found herself confronted by groups already formed within their own companies. Moreover, she mentions a dichotomy in social events, some of which were more reserved for her manager. More generally, this dichotomy illustrates the fact that some events involving professional time are reserved for those in positions of responsibility, while others, more convivial in nature, are aimed at the “general public” during lunch hours. Thus, certain conferences or meetings related to scientific and professional activities would be difficult to access for engineers or technicians who do not seem to be inclined to represent their company. However, L’Escale and other related events would bring everyone together. In reality, however, the survey shows that L’Escale is a place that is little used by managers and people in positions of responsibility.

Consequently, the low investment of management in this “non-market” space does not participate in the mode of governance implicit in the coordination of actors that has been pointed out in the literature (Saxenian 1994). The following extract testifies to this:

I think it can lead to something if the bosses are in that informal relationship; if a technician becomes buddies with another technician it won’t lead to anything (interview with Leïla, accredited company director of studies, July 2015).

For this director of studies, the informal exchanges likely to become professional collaborations take place between managers. Thus, coordination resulting from the use of conviviality places cannot be expected if they are absent. As a result, despite the constantly increasing number of registrations, L’Escale appears to be more of a service available to the biocluster’s employees than a true arena for the construction of non-economic social links that could be converted into relationships with an economic purpose. In this context, it appears difficult to compare the economic potential of L’Escale to that of the French community analyzed by Ferrary, who assures that, if a French person in Silicon Valley were looking to create a company, he/she would spontaneously turn to his/her ethnic community for advice and information during social gatherings.

As we end this chapter, we can see that cluster workers seem to encounter difficulties in terms of availability in order to participate in the various networking events, and, even when they do have the opportunity, the exchanges are rarely converted into professional collaborations.

- 1 Transcript of the General Meeting of Cluster Leaders and Decision Makers, Genoforum, December 16, 2011, p. 4.

- 2 http://www.silvervalley.fr/Animation-du-reseau.

- 3 http://www.spn.asso.fr/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Offre-Animateur.pdf.

- 4 http://www.aradel.asso.fr/upload/File/offreEmploi/fiche%20de%20poste%20cm%20animation_405142.pdf.

- 5 https://itiri.unistra.fr/uploads/media/FicheAnimateur_de_cluster1.pdf.

- 6 Within the framework of the CIFRE, I was also part of this team as a research officer attached to the General Management.

- 7 Indeed, among the people who answered that they had already participated in the WS in the questionnaire distributed online, three quarters (76%) work in a company, and are mainly managers, or even company directors. As the questionnaire was distributed on an individual scale (responses from individuals regardless of their status) and on an organizational scale (responses from managers), the results indicate that 18% of the individuals surveyed had already participated in a WS, compared to 56% of the managers surveyed.

- 8 http://www.essonne-parisud.com/lieux-de-seminaires-sans-hebergement/fiche-tourisme/genocentre/.

- 9 http://www.genopole.fr/spip.php?page=rubrique_event&id_rubrique=784&event=784#.WSRdHhPyjHg.

- 10 http://www.genopole.fr/Videos-du-colloque-medecine-personnalisee.html#.WSRcNBPyjHg.

- 11 http://www.genopole.fr/-Synthetic-Biology-From-Ideas-to-Market-.html.

- 12 Minatech is a cluster that brings together scientific and industrial players as well as training courses in the Grenoble area in the field of micro- and nanotechnologies.

- 13 These two events were quite enthusiastically attended, with between 20 and 30 PhD students present at each.

- 14 Internet portal for employees (1,400 people) of accredited organizations who pay a fee for access, which allows them to benefit from special offers on tickets, practical information (classified ads, carpooling, accommodation, etc.) and newsletters (at least once a month).