6

Personal Documentation: Between “The Self” and “Myself”

There is a reality made of the total and that is what it is. Within this reality, we see at work Man, Men and their Society within Nature. In man, an observation if not a definition and an explanation, we are led to distinguish two elements: (1) the deep, personal, lived self; long-term free qualitative mobility foreign to it; pure memory plunging into the indivisible movement of the vital impulse; (2) the intelligent self, with practical functions, with a deterministic mechanism. The two elements coexist, producing all the works with their two methods, intuition and direct knowledge for one; logic and discursive knowledge for the other. We find these two elements in the individual, in the life of society (thought, feeling, activity) and we find them in the books that are the manifestation or expression of them. (Otlet 1934, p. 116, author’s translation)

Documentary practices are clearly linked to both organizational and individual practices. Historically, individual practices of library building, private study and compilation work in the form of records have gradually been transformed into collective and institutional forms. Nevertheless, personal documentary practices have not disappeared for all that. They have been articulated with institutional and collective offers, but also empowered to respond to specific, personal and intrinsic needs that were not shared: “Sometimes my library obeyed secret rules, born of personal associations” (Manguel 1998, p. 26, author’s translation).

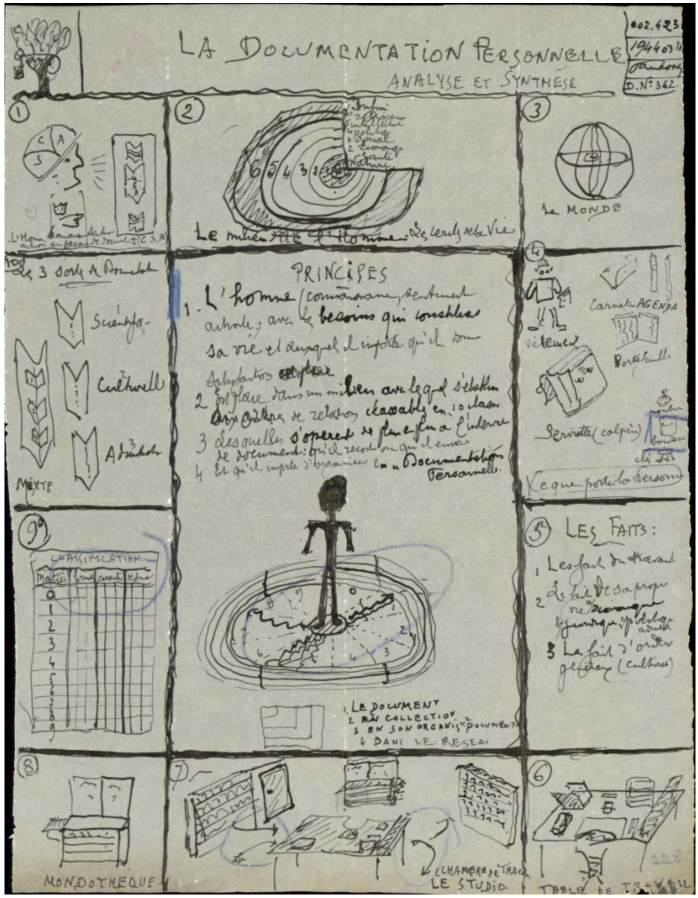

Figure 6.1. Paul Otlet: “Personal documentation”1 For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/ledeuff/hyperdocumentation.zip

However, the hyperdocumentary context tends to diminish these differences. How can we understand this relationship between documentary or “documenting” organizations, that is, organizations that produce documents and document on a daily basis, and individuals who have information and documentary needs that are extremely varied?

If we take the example of Librarything, we can see that the platform initially offered the possibility to catalog one’s own library and to use tags to categorize one’s works in a personal way. However, Librarything has become above all a reading social network that manages to link personal documentary practices with collective practices. As a result, personal practices (Figure 6.1) become interesting by being linked and compared with others to produce new forms that can be contributive.

Personal documentary practices thus constitute a mass that defines the fact that hyperdocumentation also designates that moment when a large part of this production is tipped over from private to public. Hyperdocumentation of the self, which often functions as a hyperdocumentation of self-identity, is thus observed at two levels:

- – the individual level, which can now access a number of tools and functionalities to document its own existence and to ensure a more or less long-term record of it. From the most classic office creation tools doubled by their storage in clouds, to the production of personal and family photographs that are stored on smartphones and associated services, but that can also be shared and staged, the forms of personal documentation are constantly increasing. Such storage and sharing also makes it possible to accumulate data over time that can be consulted at regular intervals. They constitute indicators of a statistical nature. We find these accounting logics on social networks where the fact of documenting and sharing one’s existence, often staged, becomes a trivialized way of life, even the way of life of new professionals who live on this documentation-projection of oneself, to the point that a candidate on a reality TV show can answer “Instagram”2 to the question “What do you for a living ?”.

- – the collective level which, it is important to understand, is impossible to detach it from the individual level. In particular, it is unthinkable to think of the question of individual data only at the personal level, since the valuation and the comparative, quantifiable and algorithmic stakes are precisely played out in this permanent perspective between the individual and others. Individual hyperdocumentation is constantly inscribed in forms of collective hyperdocumentation, and not only for the “influencers” whose visibility allows them to reach a very large audience, but also for the simple user whose publications are part of a complex informational ecosystem that will encourage him/her to produce content as much as to consume it in a targeted manner. The very act of consulting and searching for information is an essential form of documentation, whose hyperdocumentary interest lies in being able to preserve and compare it in order to create recognition schemes. These patterns are stakes for the algorithmic choices that will be defined, but they are above all marketing and managerial choices that consist in anticipating potential trends and identifying them in order to better encourage and duplicate them. There are professions dedicated to these logics, and William Gibson's novel, Pattern Recognition, gives an overview of them:

What I mean is, no customers, no cool. It’s about a group behavior pattern around a particular class of object. What I do is pattern recognition. I try to recognize a pattern before anyone else. (Gibson 2004)

In this way, practices on the margins can gradually become widespread and shared practices, even in a short period of time. One of the key markers is therefore to have succeeded in tilting practices that are sometimes discreet, egocentric, idiosyncratic, ephemeral, very personal, into forms of visibility that range from the constitution of a personal profile with very intimate aspects in the most advanced cases to statistical forms that take collective forms as trend indicators, Google Trends types which function as indicators of the interest for current events of the period, but which also occasionally show unflattering aspects of a humanity which proves to be xenophobic, macho or conspiracy-obsessed when it is not all three at the same time.

Personal documentary practices can now also rely on possibilities heretofore reserved for companies and professionals. Individuals can enter indicators for their own governance. This includes all time management tools, to-do lists, Kaban-type systems, etc. But the stakes go far beyond semi-professional frameworks.

6.1. Renewal of personal documentary practices

Statistics, etymologically linked to the fact that the State produces data to better understand the country’s situation, have gradually shifted to private organizations as well as to individuals who can record the statistics of their actions via recording devices such as smartphones. Self-quantification is part of this framework, which consists of recording the slightest of one's actions in order to be able to study them.

Initially a marginal practice, it is now present in an automated way within smartphones that record and measure the distances traveled, the sports performances achieved. It has therefore become commonplace through the development of statistical uses at the personal level, which even allows for quantified self.

This practice is not totally new. It even preceded the development of connected tools with people who wrote down in their personal documents all the actions carried out in a day. Researcher Stephen Wolfram, creator of the Wolfram Alpha search engine, has been working on himself in this way for years. Obviously, the potentialities of digital technology allowed him to better manage this cumulative form.

Among the data sets, the most adequate are the e-mails, especially those sent. Wolfram was thus able to produce a personal analysis from 20 years of email3. The logic can equally take into account telephone communications, but also the number of keystrokes, all in order to distinguish lasting personal trends or to guide personal life strategies. Wolfram’s example is part of the “personal analytics” that join the development of joint trends in its ability to manage its information and dedicated tools, as in the case of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) or Personal Learning Environment (PLE).

More and more, the goal is to manage the consequences of “passive data” in order to try to make the choices recommended by applications.

But there are more traditional forms of recording achievements made in a day or even encounters made with other people, including sexual or romantic encounters, by writing them down. Diaries and other such productions are already self-documentary forms, and their continuation over the years opens up other possibilities for self-reading. The blending of genres between family narratives and bookkeeping is also found in account books, a practical tool for the craftsman and trader and his descendants, but an even more valuable long-term tool for historians.

The production of “memory supports” or hypomnemata in the sense of Michel Foucault is not new, but its trivialization and multiplication is a symbol of this hyperdocumentary era.

Among these hypomnemata are notebooks, both paper and in the form of files on a personal computer. From the need to organize one’s life, between the annotated diary and the to-do-lists that follow one another, to the more recent practices of the bullet journal, these are forms of daily life management that can take more surprising forms if they are reread a few years later. For nothing ultimately compels us to go back on what has been compiled. But the exercise remains essential for many individuals who can also take a certain pleasure in developing an aesthetic in this work of writing of oneself. Interesting are also the software programs that accumulate notes, to classify them, to tag them and even better to associate them by hypertext links. This hypertextual path then offers the possibility to navigate in a different way than tree logic and tries to reproduce in some ways the mental path, in the manner of Vannevar Bush’s text.

Even annotations on books are part of these forms between self-writing and documentary production. Very often their significance is only understandable by the annotator. The ideal being to be able to navigate and find one’s notes, traces, annotations, reading and writing paths in order to better grasp potential intellectual relationships. The markdown type text editors seek to reproduce the logic of the interlinked cards as in the example of the Obsidian software which offers the possibility of navigating in a cartographic way between its note cards. It is even possible for the annotator and the recorder to go back in his path when he has just produced several notes in a row.

Undeniably, personal documentary forms remain essential, because they are often, especially among knowledge workers, forms that precede largerscale collective projects that range from the transformation of records into articles or books, to encyclopedic-type logics. It now remains to identify the Conrad Gesner, Adrien Baillet or Theodor Zwinger of our time in order to better grasp the documentary needs and the new forms that will emerge from these practices, particularly at the semantic level (Kembellec 2019).

These forms, worthy of the digital literates (Cormerais and Le Deuff 2014), constitute protodocumentary forms in the sense of both a read-write prototype and methods and strategies for organizing knowledge. They probably precede new hyperdocumentary tracks that allow us to envisage a free hyperdocumentation, to which we will return in Chapter 9. These practices, both proto and self-documentary, are the roots of more ambitious and larger projects. If they once made it possible to move from the card to the bibliography or encyclopedia, new transformations must now be envisaged. When Tim Berners Lee developed the Enquire software for his own documentary needs, the idea was to propose a software for circulating between notes, following the example of the HyperCard software in the 1980s. The initial hypertextual logic envisaged by Berners-Lee was thus to be found in the web project. These filiations, legacies and successive transformations are currently found in experiments, particularly scientific experiments in the field of digital humanities. The HyperOtlet project, dedicated to the work of Paul Otlet and especially to the Traité de documentation, is fully in line with these logics, by seeking to “document the documentation”4.

However, self-documentary forms are not exclusive to knowledge workers and other researchers. For example, the data card, a form long favored by intellectuals, is now being transformed and used in the recovery of the essential information it contains to maximize metadata management. The card form sometimes returns in forms that bring it aesthetically closer to its original forms, such as playing cards. The latter were in fact used for note-taking thanks to reverse sides that could be annotated. Later on, the format was reused to catalog libraries, as was the case in France with Abbé Rozier (1734–1793), who allowed the beginning of bibliographic standardization with his Nouvelle table des articles contenus dans les volumes de l’Académie royale des sciences de Paris, depuis 1666 jusqu’à 1770. The King’s librarian, Lefèvre d’Ormesson (Fayet-Scribe 1999) would continue the initiative in the form of a collective catalog of France.

Examples of data cards can now be found in interfaces, especially those meant for meetings such as Tinder. Symbol once again of the passage between indexing knowledge and indexing lives, Tinder makes it possible to see but also to manipulate (swipe left or right) the cards that represent people. Obviously, all the profiles generated by social networks are forms of cards whose manipulation escapes the profiled, but which are indeed hypomnemata.

As Stiegler (2008) in particular shows, these hypomnemata have now taken on other forms that concern a much wider and not necessarily literate public. Memory media have evolved into memory “offsets”, short transactions that are forms of short-term gains that must constantly be repaid through long-term loans. Except that here the creditors are the existence management platforms that manage to profit in the short and medium term from the self-documented forms and other writings of the Ego.

If the interest of social networks appears in more than one way obvious due to the possibilities of connection and exchange that they offer, their weakness comes not only from the problems of the attentional mechanics, but also and especially from the fact that they absolutely do not constitute writings of oneself, as it was possible to hope, but matrices of the Ego which sometimes prove to be destructive or generators of frustration or even depression. We are sometimes closer to an externalized conversion to the current imperatives of communication than to a conversion in oneself. To return to Foucault’s work on exomology, we are more in the Christian than the Stoic model:

Ostentatious gestures have the function of revealing the truth of the sinner's very being. The revelation of oneself is at the same time the destruction of oneself. (Foucault 1994, p. 808, author’s translation)

We must therefore develop what could be a documentation of the self as an art of the self.

6.2. Self-documentation

Documentation, theoretically and practically, cannot be separated from the consideration of the documentation of oneself. Omnipresent in all its aspects, it is also prized by Otto Neurath who is personally interested in the documentation of himself, undertaking a graphic self-documentation, a visual autobiography.

This is not anecdotal, since thinkers such as Otlet or Neurath had clearly understood that one could not claim to change the world without changing oneself, and that to do so one had to come to understand oneself, in an introspective form that could not be disconnected from a globalized perspective.

It is thus a question of being able to understand oneself, an inner self that one must in some ways be able to catalog.

For Otlet, it is in any case a question of envisaging the documentary exteriorization of thought:

How can any thought, whether it is pure intellect, feeling and emotion, or tendencies and wills; whether it refers to the self or the non-ego, how can any thought be expressed by means of documents, that is to say, physical and corporeal realities, incorporating or supporting the said data of thought with the help of signs or forms or differentiated elements perceptible by the senses and connected to the mind by correspondence. (Otlet 1934, p. 25, author’s translation)

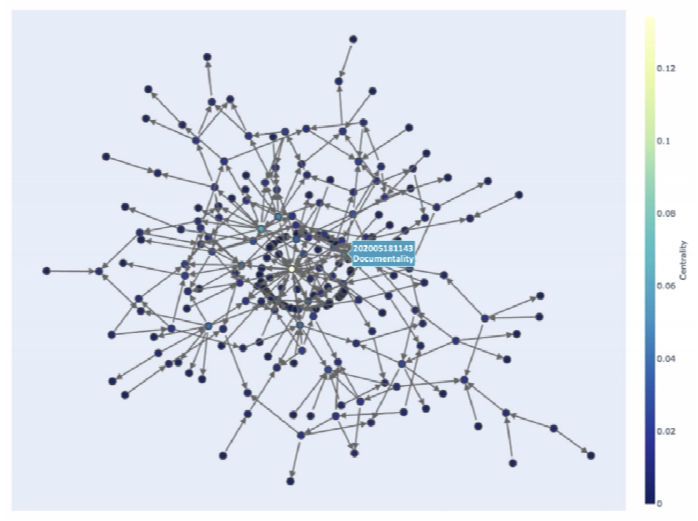

The ideal is thus the documentary transposition of the conscious and even the unconscious. In any case, it is a question of an awareness of one’s own knowledge and thus one’s lack of knowledge as well. This relationship is essential, because it strongly influences the search for information. The need for information is based on an externalization of personal knowledge towards the outside. It is as much a form of expression of expertise (I know that I don’t know) as it is a form of confession (I confess my ignorance), which obliges us to take stock of the knowledge we possess or think we possess, and the documentation we have. Arthur Perret5 clearly shows through his personal approach that it is possible to create a “hyperdocumentation” from a rigorous management of his note cards in order to map the work being done in the form of graphs (Figure 6.2). The graphical representation makes it possible to manage the centralities linked to projects, such as a thesis for example, and to visualize the elements that are well interrelated and those that remain for the moment pending new correlations.

Figure 6.2. Arthur Perret: Visualization of reticular personal documentation. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/ledeuff/hyperdocumentation.zip

Documentation is therefore first and foremost a self-documentary process that requires us to situate ourselves in larger groups.

Each individual has an internal and external behavior: knowledge of the perceived object and judgment on it, feeling and reaction, after internal deliberation, will and action. The operations are almost simultaneous and as three aspects of the same thing: position of the least resistance, behaving according to the immediate; position according to the ideal, behaving as if each of his acts collaborated in the realization of the entire universal work. (Otlet 1935, p. 337, author’s translation)

Henceforth, the documentation of the self is as much an art of the self as it is a liberal art (Le Deuff 2019). That is to say, it is impossible in the end to be able to access the intellectual and spiritual meaning of the cosmoscope, the ultimate instrument of hyperdocumentation, without this prior work. Somewhere in Otlet’s work, we find a form of inner quest:

The great problem remains: to find or give meaning to life; to develop all the latent powers that one has within oneself; to form one’s inner self and not only one’s outer self; to live passionately and harmoniously in the three domains where science, art and action develop; to realize a universal self. (Otlet 1935, p. 345, author’s translation)

In Otlet’s work, this universal self comes to position itself among the society of spirits, within other fragmentary elements such as the nation or the family, and all other forms of association. In Otlet’s case, it is thus a question of going beyond atomism to seek the links between the different elements in order to connect the self to larger entities. And this requires the ability to take notes, to organize them, and finally to be able to potentially link certain cards with contributory value even if they were initially constituted for personal documentation purposes. It is a logic of project and projection that turns personal documentation into an encyclopedic aim.

The NOP project that brought together Paul Otlet, Otto Neurath and Anne Oderfeld is a good example of the desire to merge individual documentary projects that have grown collectively into an even larger “orb”, that of a meta-organizational project. NOP signifies several things: “Novus Orbis Pictus” to show the construction of an encyclopedic and didactic project of knowledge in the line of that of Comenius and his Orbis sensualium pictus, intended for children wishing to learn Latin through pictorial forms. NOP can also mean New Orbis Neurath to Paul Otlet, July Pictus. NOP also refers to a play on words such as “Neurath Otto-Otlet Paul” as the project appears as a fusion of the two men’s aspirations to bring together projects such as the Mundaneum, encyclopedias and more particularly to set up educational exhibitions. Finally, it is simply Neurath-Oderfeld-Otlet-Paul, because the project clearly appears as a triptych. The fact remains that Anne Oderfeld’s work deserves further examination, particularly in its connections with Otlet and their joint publications (Otlet 1929), but also in their shared didactic and encyclopedic ideals (Oderfeld 1928) and their shared desire to create self-educating material.

Otlet and Neurath’s encyclopedic and classification work aimed to give an overall vision of knowledge during a period that Otlet described as hyperseparatism, marking here both nationalist temptations, but also the disciplinary divisions at the scientific level that divided researchers into spheres that ended up no longer exchanging. Hence the need to produce means of creating links, inter-documentary forms that connected knowledge. But it should be remembered that in Otlet’s work, it was indeed essential to place the individual and his Self in these constructions. Georges Bataille, the instigator of the famous review “Documents” which oscillates between ethnology and art history, even pleads for a return to the self as a means of escaping the will to seek knowledge from outside the world, which is the result of diverse constructions:

It is the separation of terror from the realms of knowledge, of feeling, of moral life, which obliges one to construct values uniting on the outside the elements of these realms in the forms of authoritative entities, when it was necessary not to look afar; on the contrary, to reenter oneself in order to find there what was missing from the day when one contested constructions. ‘Oneself’ is not the subject isolating itself from the world, but a place of communication, of fusion of subject and object. (Bataille 1988, p. 9)

In Bataille’s work, the self becomes a place, or rather a milieu, which allows the articulation between the subject and the objects that surround it. In Bataille, the fusion is essentially spiritual in nature, based on a form of mastery of inner experience. Increasingly, however, the devices seem to short-circuit this inner experience in order to externalize it as much as possible.

6.3. Self-demonstration or self-documentation

Space itself has long been conceived as a void that would be filled by things. (Secular discussions on emptiness and fullness). But one must recognize a double active action in space. (1) If space is a creation of the mind (Kant’s a priori synthetic judgment), such a creation leaves its mark on everything that is thought. The clearer, more conscious and evolved the notion is, the stronger its action will be, the greater its importance. (2) Space is not only a place, it is a milieu. All the things that occupy it are brought to have relations with each other. There is connivance in the same space and thus the environments become active. Things there respect an ‘interior space’ delimited by the confines of the thing and placed in an exterior space. Things are thus influenced from the outside to the outside. (Otlet 1935, p. 305, author’s translation)

Hypomnemata have thus spread to the point where it is difficult to affirm at this time that our documents are really private. Incentives to duplicate them in the cloud, or even to produce them directly in online platforms, show that we have moved beyond the attempt to distinguish between “intimate” and “extimate” diaries to qualify blogs. Memory media are documentary externalizations that tend to become supports of outlet and emotions. They actually require new skills and mastery (Le Deuff 2019b).

The awareness that these memory supports can make sense has transformed their scope, initially individual, to a public and strategic scope, which then becomes cumulative, even collaborative. If one of the frameworks of self-writing and other techniques of self can be found in introspective exercise, such as that of recording dreams as Freud advocated for example, the confusion is all the greater because the desire to transform the individual personal construction into a marketing instrument is found among the proponents of “personal branding”. If the discourses focus on the principle of defending one’s own personal brand to distinguish oneself, the mechanisms reduce them to measures of one’s activity, mixing the concepts of reputation, influence, authority, popularity and legitimacy to focus on indicators such as the number of followers, for example. Obviously, drops in these numbers place the individual in a spectrum that equates them to the stock market price of a share, thus falling prey to psychological cracks or at least to a certain amount of distress in the event of a drop in success. The accounting effect it represents leads to a substitution of the qualitative for the benefit of a quantitative performance. In this way, the systems favor what performs rather than what transforms. Transformation is to be understood here as transformation within oneself, in the sense of being able to improve oneself. Yet this search for performance, for a transformation of the self, seeks to meet the criteria of conformity. The end in itself seems to be dictated by a scoring, the will to be seen and heard, to be shared. From that point on, the devices seek to produce “attachments” whereas the techniques of the self are the opposite of the practices of “detachment” which consist in being able to make one’s own person evolve in one’s knowledge of a subject, but also in one’s knowledge of oneself. Michel Foucault expressed this in an interesting way when he evoked his work of writing:

The idea of a borderline experience, which tears the subject away from itself, is what was important to me in reading Nietzsche, Bataille, Blanchot, and which has meant that, however boring, however erudite my books may be, I have always conceived them as direct experiences aimed at tearing me away from myself, at preventing me from being the same. (Foucault 1994, p. 43, author’s translation)

The Foucauldian approach is different from that advocated by marketing, which on the contrary paradoxically encourages people to “be themselves”, to express their “self” or to “come as you are”, because the goal is not to change themselves, but rather to adopt new habits and practices. Nevertheless, transformations still occur, which oscillate between in-formation and conformity.

This drift is the consequence of a transformation of personal practices into publicized practices that are based on the will to demonstrate the interest of one’s own existence, especially with regard to others. The basic principle is that of a repeated presence at high frequency in order to be certain to remain constantly visible. In this sense, the production of selfies differs greatly from self-portraits in that it is part of a totally different, even opposite, relationship to time:

Self-portraits can be in any medium, but selfies can only be photographic – and generally only taken on smartphones. Both forms of representation depict their creators, but the self-portrait seems to emphasize the creator’s inner life, whereas the selfie emphasizes the outer life: Self-portraits manifest meditations on, for instance, possibility and death, while selfies limit themselves to the immediate environment. Self-portraits may be kept to oneself, while selfies are virtually always shared. Self-portraits are singular, and selfies are multiple. Selfies are a form of phatic communication; to the extent that self-portraits are communicative, they are substantive. Self-portraits are made to last, but selfies are for now. (Gorichanaz 2018, p. 100)

The selfie is characteristic of the will to mark a continuous present that requires winning recognition which must be constantly replayed. But selfies are not the only self-documentary productions, they represent only a part, concerning less than 5% of the productions on a network like Instagram. In this respect, the selfie proves to be close to the messages on social networks that Yves Jeanneret qualifies as Micro-Documentary Exchange Devices (MDEDs). Jeanneret also deplores the fact that these devices function as “requisitions” or injunctions to produce messages, because they are places where one must now live one’s social existence:

More generally, the semiotic material that suggests the status of the Internet medium and its ‘mobile’ extensions has the property of representing the medium, not as a tool for expression and transmission of thought, but as a place in which one must live, or even the only place in which subjects access social existence in the full sense. This is what we call requisition. (Jeanneret 2015, p. 10, author’s translation)

One of the current deviations is precisely the will to show what we do and to give a deeper meaning to each action. This is particularly noticeable among those who want to give a political or spiritual meaning to their actions. It is a manifestation of intellectual superiority which is in fact a form of contempt for others, and which obviously ends up generating comments or negative reactions out of weariness ... which only strengthens the position of the criticized people who then see it as a form of confirmation of their actions. It should be noted that these logics are very present among educated people and not only among ordinary citizens. Antoinette Rouvroy sums up this proximity between a quantitative logic and the extension of activities that index individuals in a performative way:

We can also observe a complicity, or at least a parallel, between certain neoliberal modes of government and the way in which individuals experience themselves as having no value other than indexed on their popularity in social networks, on the number of citations of their work, on all this sort of self-quantification. This ‘machine’ aspect affects individuals in the way they construct themselves autobiographically, biographically, in the way they conceive of themselves. This explosion of data, but also of forms and people, is a hyperindexing of absolutely everything, including the personal form. Something seems to me to be very worrying: the fact that individuals themselves come to conceive of themselves only as hyperquantified – we speak of the quantified self – as having value only in relation to the outside, to the performances of others. This is indeed the case in a hypercompetitive society, including at the level of subjectivation and individuation. (Rouvroy and Stiegler 2015, p. 110, author’s translation)

This observed hypercompetitiveness works on renewed indexing mechanisms powered by performances of self which very quickly concern most social network users, especially the youngest, who will thus measure the success of their presence by the number of likes or follow-ups generated. The documentary identity thus produced is an identity made measurable:

Today on the Internet, through more advanced algorithms and indexing techniques and technologies, ‘texts’ (understood broadly to mean human-understood inscriptions), and persons and other beings are made into documentary identities. Authors and other types of individuals are asserted by names, personal qualities are asserted by a person’s ‘likes’ and ‘dislikes’, social contacts, previous searches, and other attributions; and, human and nonhumans are made into media personalities (e.g. videos of Henri, ‘the existentialist cat’, making the rounds in 2012 and 2013) by their popular indexing within documentary cultural and social economies. Newer computer-mediated postcoordinate searching and algorithms introduce a greater ability to develop time-valued and space sensitive social and cultural inferences. Through recursive and social algorithms historical and social dimensions to the documentary subject’s knowledge are added. (Day 2014, p. 86)

From then on, even if awareness gradually increased regarding the phenomena of passive digital identities and the resulting data capture, other mechanisms worked in the opposite way, seeming to liberate expression with paradoxical phenomena that consist in constantly criticizing powers or imagining plots using tools that really struggle to ensure the quality of information, because their economic model is precisely based on an abundance of content to keep a large number of Internet users loyal.

It is a question of frequently demonstrating not only that one exists, but that one’s existence is more interesting than that of others. It is obviously the strategy of influencers to be able to display a superior lifestyle, which makes the common human dream. It is also a transformation of idleness as otium into a form of work or neg-otium, which consists in producing a form of work that is based precisely on the demonstration that, on the contrary, the influencer does not really work and instead simply enjoys life. Whether this is true or totally constructed, the demonstration here differs from the traditional models of self-expression which consist in showing or fabricating an inner richness that could be exposed through documents gathered around a personal library. The Des Esseintes library corresponds well to this description:

The works of the following centuries were sparse in the library of Les Esseintes. However, the 6th century was still represented by Fortunat, the bishop of Poitiers, whose hymns and Vexilla regis, carved from the old carrion of the Latin language, spiced with the spices of the Church, haunted him on certain days; by Boëce, the old Gregory of Tours and Jornandès; then, in the seventh and eighth centuries, as, in addition to the low Latinity of the chroniclers, the Frédégaire and Paul Deacon, and the continuous poems in the Bangor antiphonary, whose alphabetical and monotonous hymn, sung in honor of Saint Comgill, he sometimes looked at, literature was confined almost exclusively to biographies of saints, in the legend of Saint Columban written by the cenobite Jonah, and that of Blessed Cuthbert, written by Blessed Bede the Venerable on the notes of an anonymous monk from Lindisfarne, he merely leafed through in his moments of boredom, the work of these hagiographers and to reread some extracts from the life of Saint Rusticula and Saint Radegonde, one, by Defensorius, synodite of Ligugé, the other, by the modest and naive Baudonivia, a nun from Poitiers. (...) Except for a few special volumes, unclassified, modern or undated; some works on Kabbalah, medicine and botany; some mismatched volumes of Migne’s patrology, containing Christian poetry that could not be found, and of Wernsdorff’s anthology of small Latin poets, apart from the Meursius, Forberg’s manual of classical erotology, moechialogy and the diaconal books for confessors, which he dusted off at rare intervals, his Latin library stopped at the beginning of the 10th century. (Huysmans 1922, pp. 75–76, author’s translation)

While the description is that of a library, it is clearly in fact a description of an individual and what constitutes and stimulates his mind. Thus, it is about displaying references, places, desires, achievements. It seems to me that we haven’t given enough consideration to the strong relationship that exists between the card (fiche) and the poster (affiche)6. The purpose of the poster is to make public, to reveal to others. It is a form of communication that seeks publicity, but this sharing with others lies in forms of imbalance, of communicational jousting, even of informational guerrilla warfare. The banal, which may ultimately be common, may then deserve to be transformed into a communicable element. The common then becomes at the same time a kind of retreat into the mediocre, in the sense of the average and the medium, to be in a logic of similarity (“common people like you”7) while seeking to add something that allows this form of distinction, the display of something that wishes or claims to be, out of the ordinary.

Self-documentation, as a space for self-satisfaction, thus becomes the instrument of hyperdocumentation, with the speeches of freedom that accompany it. But freedom sometimes proves to be much more circumscribed than it appears.

6.4. Documentary freedom under constraints

The ease of use, the fact of being able to put documents online in an almost unthinking way is apparently the consequence of a democratization of publication and of the rhetoric of free speech which moreover accompanied for a time the possibility of creating blogs.

But this freedom of expression is an illusory or constrained freedom that finally joins that of free air radio and blog platforms that leave you a freedom that is in fact “framed” by “narrative constraints”:

Recorded memories tend to freeze the nature of their subject. The more memories we accumulate and externalize, the more narrative constraints we provide for the construction and development of personal identities. Increasing our memories also means decreasing the degree of freedom we might enjoy in defining ourselves. Forgetting is also a self poietic art. A potential solution, for generations to come, is to be thriftier with anything that tends to fix the nature of the self, and more skillful in handling new or refined self poietic skills. Capturing, editing, saving, conserving, and managing one’s own memories for personal and public consumption will become increasingly important not just in terms of protection of informational privacy, as we shall see in the next chapter, but also in terms of a morally healthy construction of one’s personal identity. The same holds true for interactions, in a world in which the divide between online and offline is being erased. The onlife experience does not respect dimensional boundaries, with the result that, for example, the scope for naive lying about oneself on Facebook is increasingly reduced (these days everybody knows if you are, or behave like, a dog online). (Floridi 2013, p. 223)

Behind the speeches that constantly call for “free expression” “to be oneself” are paradoxical injunctions that aim to smooth out differences, or at least to express them in very similar ways that allow their exploitation, commercial, political, ideological, and therefore their potential reproducibility. Apart from the aporia of spontaneity, how is it possible to be oneself when we are forced or incited to be? How can we finally be innovative when others have determined in our place what innovation should be?

Expressing oneself in constrained forms or frames of thought is not new. Poetry fits precisely into these logics, it appears however that the awareness of its constraints is very little perceived because, on the contrary, the marketing discourse and the affordances make us believe that there are precisely no more constraints. What has increased in the perception of limits and risks are above all questions about personal data and targeted advertising. Much less perceived are the compliance mechanisms and the technical and formal constraints that platforms impose on uses, especially since they are accompanied and coupled with social mimicry.

For Colin Koopman, our identities are forged by data and the frameworks within which it is produced:

Like any swaddling, our data are both constraining and comforting. Information opens up possibilities for what we can be. Yet it also forecloses possibilities for what we cannot be. Like a newborn whose movement is restrained by tightly tucked fabric, we are soothed by data that calm us into stillness and eventually into unthinking sleep. We learn to live within the formats of our information and eventually come to depend on them. These dependencies are dangerous, because where we all find ourselves formatted, it is possible for us to be formatted unequally, even unjustly, and without anyone, including those who most benefit, ever intending it. (Koopman 2019, p. VII)

The apparent ease, the reduced or even short-circuited time for reflection, are part of a freedom of expression that is that of a strongly limited countergift, as the platforms and devices do not guarantee anything other than “publicity” in the sense of being made available in public places that are only public because they are available, but which are in fact managed by private actors.

In the economy of Web 2.0 discourse platforms, this freedom and ease of use feed data and content to devices. Platforms are first and foremost service providers seeking to become content providers in order to achieve economic profitability. In order to achieve this more easily, the displayed diversity of content makes it possible to reach a wider audience, and what is private or very personal therefore becomes interesting. Quantity is the goal rather than quality and selectivity.

From that point on, the documentary masses with a low general scope become opportune elements to put online so that everyone can benefit from their 15 minutes of fame. The injunctions to express oneself function as requisitions whose goal is the retention of informational elements that can make attentional strategies work. Hyperdocumentation can then function as a destruction of the self, as it becomes so difficult for the individual to “detach” in order to take the time to find himself again in himself.

Hyperdocumentation manages to use the fact that man is the only living being that needs to be dressed. In fact, we increasingly wear not only clothes, but connected devices. The objective is then to naturalize the connected objects to make them enter into everyday life in the same way as one wears a garment, or to make them into clothing outright. However, these devices are more and more oriented towards young audiences, especially children. In addition to the fact that they contain geolocation information and information on their use, wearing them from a very young age allows the formation of a habit that touches the corporality of the child and the future adult.

Finally, the discourse of freedom of expression conceals constraints and logics that are sometimes those of architext, such as typographic legacies and software that frame our practices of writing or putting content online, but also frameworks and patterns of thought that standardize the design of interaction and the possibilities for real innovation. Very often, the tool that appears to be the easiest to use, because it does not require much skill and learning time, can sometimes prove to be a decoy or even an obstacle to real freedom and potentiality of expression because the result is so constrained technically, but also by the modalities of use that facilitate the reproduction of forms and imitation rather than innovation.

Koopman considers that the incitement or “requisition” to act, to use Yves Jeanneret’s expression, functions as a form that is somewhat constrained and “instructed” by the system:

We do exactly what the computer instructs us to – and most especially when we cannot get it to do what we want. And yet the designs of data are anything but immutable forms that we must acquiesce to. In investigating the history of information, we establish contact with the mobility and manipulability of data technology. For we can find in that history a set of moments when data was not yet closed, but rather glaringly open to contestation and recomposition. (Koopman 2019, p. ix)

Somewhere there is a programming reversal. Without falling into the dichotomy between “programming” and “being programmed”, it is necessary to question the conditions of production of the injunctions, and to understand how to resist them, or even how to re-program their intentions.

6.5. Hypodocumentation or the concept of sousveillance

Hypodocumentation is correlated to this production of hypomnemata, it therefore designates the possibilities of documenting and documenting ourselves in such a way as to respond or even resist mechanisms that tend to hyperdocument our existences without our real consent. Hypodocumentation here joins the concept of sousveillance. Steve Mann (2003) developed this concept as a hijacking of the tools of citizen control. We find here a logic close to drifting machines, as it is about reusing tools for other purposes, or even reversing the point of view of control machines. Obviously, this logic is initially close to copwatching devices insofar as their aim was to show police exactions by filming them during their realization.

But the concept goes further. It consists in fact of using tools similar to those of surveillance devices, including the possibilities of the famous surveillance cameras that operate according to panoptic logic as well as conservation logic.

The panoptic here is reversed, in a logic that consists instead of looking from below. The look is therefore not overhanging, it is underlying, and allows you to produce documents with all the tools that allow you to film with your smartphone in particular and to produce it live or even slightly delayed. The hypodocumentary logic can be explained by the fact that it is a question of users regaining control of the hypomnemata, and that it is possible to give them a deeper collective meaning through its communication and advertising.

Nevertheless, hypodocumentation remains a form of hyperdocumentation, but a derived form. And all the more so because it must be understood not by studying only its fragmented forms that can be found on Periscope or Twitter, but in the possibility of forming a more coherent whole as on copwatching sites or on David Dufresne’s site for the newspaper Médiapart on police violence, “Allo place Beauvau?”8. The compiled, assembled form makes it possible to produce a new work that emerges from the fragmentation of the news item to give it a new meaning, with political significance, certainly, but with documentary value by going beyond the logic of warning to the citizen that dominated until then in France:

In France, associations and collectives then proposed to create a common intelligence pool, to make accessible information of interest to the very structures that allow this surveillance, whether it is carried out by States through specialized software, on a daily basis by surveillance cameras, or whether this surveillance is legitimized by the constant evolution of the legislative framework. What these citizens’ groups call sousveillance is therefore more a matter of providing an overall view of the surveillance devices (mainly technical and legislative) that have been documented by the most visible actions of the monitors. (Alloing 2016, p. 71, author’s translation)

Nevertheless, difficulties remain in truly moving away from crossmonitoring logics. Indeed, those who practice sousveillance are not certain to avoid being monitored in a more traditional manner, because their production of information will necessarily generate interest, particularly on the part of official intelligence services. Inevitably, putting documents online leads to the production of metadata that facilitates identification. If some journalists or self-reported journalists have chosen to assume their identity in the hope of being protected in this way, this situation seems unlikely in nondemocratic countries.

The spirit that is being developed is that of making transparent the actions of governments, their police, but also those of the “dominant”. It is probably necessary to link these phenomena with those that consist in revealing documents via “whistleblowers”. In all cases, the most frequent aberrations are those of the resulting mistrust of government authorities, but also of the trivialization of the status of documents, which sometimes become used indiscriminately while their status, their context of creation and their real scope are sometimes neglected in favor of a form of sensationalism.

The risk is that of a generalized doubt about the quality of the information, and a permanent distrust and mistrust. One of the ways out would be to recall the interest of vigilance in relation to monitoring, and that vigilance also means regaining a bit of benevolence.

- 1 Mundaneum Archives: Mundaneum _A400186.

- 2 Reality TV show on Netflix, Too Hot to Handle (2020).

- 3 Wolfram, S. (2012). The personal analytics of my life – Stephen Wolfram writings. Stephen Wolfram Writings [Online]. Available at: https://writings.stephenwolfram.com/ 2012/03/the-personal-analytics-of-my-life/.

- 4 On the HyperOtlet project. Available at: https://hyperotlet.hypotheses.org/.

- 5 Perret, A. (2020). Visualisation d'une documentation personnelle réticulaire, June 25 [Online]. Available at: https://arthurperret.fr/2020/06/25/visualisation-documentation-personnelle-reticulaire/.

- 6 As you can see, the relationship is clear, especially linguistically, between the French terms “fiche” and “affiche”.

- 7 Pulp (1995). Common People. Island Records, London.

- 8 Available at: https://www.mediapart.fr/studio/panoramique/allo-place-beauvau-cest-pour-un-bilan.