Event-driven programming is a paradigm of system architecture where the logic flow within the program is driven by events such as user actions, messages from other programs, or hardware (sensor) inputs.

In event-driven architectures, there is usually a main event loop, which listens for events and then triggers callback functions with specific arguments when an event is detected.

In modern operating systems such as Linux, support for events on input file descriptors such as sockets or opened files is implemented by system calls such as select, poll, and epoll.

Python provides wrappers to these system calls via its select module. It is not very difficult to write a simple event-driven program using the select module in Python.

The following set of programs together implement a basic chat server and client in Python using the power of the select module.

Our chat server uses the select system call via the select module to create channels where clients can connect to and talk with each other. It handles the events (sockets) that are input ready–if the event is a client connecting to the server, it connects and performs a handshake; if the event is data to be read from standard input, the server reads the data, or else it passes the data received from one client to the others.

Here is our chat server:

# chatserver.py

import socket

import select

import signal

import sys

from communication import send, receive

class ChatServer(object):

""" Simple chat server using select """

def serve(self):

inputs = [self.server,sys.stdin]

self.outputs = []

while True:

inputready,outputready,exceptready = select.select(inputs, self.outputs, [])

for s in inputready:

if s == self.server:

# handle the server socket

client, address = self.server.accept()

# Read the login name

cname = receive(client).split('NAME: ')[1]

# Compute client name and send back

self.clients += 1

send(client, 'CLIENT: ' + str(address[0]))

inputs.append(client)

self.clientmap[client] = (address, cname)

self.outputs.append(client)

elif s == sys.stdin:

# handle standard input – the server exits

junk = sys.stdin.readline()

break

else:

# handle all other sockets

try:

data = receive(s)

if data:

# Send as new client's message...

msg = '

#[' + self.get_name(s) + ']>> ' + data

# Send data to all except ourselves

for o in self.outputs:

if o != s:

send(o, msg)

else:

print('chatserver: %d hung up' % s.fileno())

self.clients -= 1

s.close()

inputs.remove(s)

self.outputs.remove(s)

except socket.error as e:

# Remove

inputs.remove(s)

self.outputs.remove(s)

self.server.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

ChatServer().serve()Note

Since the code of the chat server is big, we are only including the main function, namely the serve function here showing how the server uses select-based I/O multiplexing. A lot of code in the serve function has also been trimmed to keep the printed code small.

The complete source code can be downloaded from the code archive of this book from the book's website.

The chat server can be stopped by sending a single line of empty input.

The chat client also uses the select system call. It uses a socket to connect to the server, and then waits for events on the socket plus the standard input. If the event is from the standard input, it reads the data. Otherwise, it sends the data to the server via the socket:

# chatclient.py

import socket

import select

import sys

from communication import send, receive

class ChatClient(object):

""" A simple command line chat client using select """

def __init__(self, name, host='127.0.0.1', port=3490):

self.name = name

# Quit flag

self.flag = False

self.port = int(port)

self.host = host

# Initial prompt

self.prompt='[' + '@'.join((name, socket.gethostname().split('.')[0])) + ']> '

# Connect to server at port

try:

self.sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

self.sock.connect((host, self.port))

print('Connected to chat server@%d' % self.port)

# Send my name...

send(self.sock,'NAME: ' + self.name)

data = receive(self.sock)

# Contains client address, set it

addr = data.split('CLIENT: ')[1]

self.prompt = '[' + '@'.join((self.name, addr)) + ']> '

except socket.error as e:

print('Could not connect to chat server @%d' % self.port)

sys.exit(1)

def chat(self):

""" Main chat method """

while not self.flag:

try:

sys.stdout.write(self.prompt)

sys.stdout.flush()

# Wait for input from stdin & socket

inputready, outputready,exceptrdy = select.select([0, self.sock], [],[])

for i in inputready:

if i == 0:

data = sys.stdin.readline().strip()

if data: send(self.sock, data)

elif i == self.sock:

data = receive(self.sock)

if not data:

print('Shutting down.')

self.flag = True

break

else:

sys.stdout.write(data + '

')

sys.stdout.flush()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print('Interrupted.')

self.sock.close()

break

if __name__ == "__main__":

if len(sys.argv)<3:

sys.exit('Usage: %s chatid host portno' % sys.argv[0])

client = ChatClient(sys.argv[1],sys.argv[2], int(sys.argv[3]))

client.chat()In order to send data to and fro via sockets, both these scripts use a third module, named communication, which has a send and a receive function. This module uses pickle to serialize and deserialize data in the send and receive functions, respectively:

# communication.py

import pickle

import socket

import struct

def send(channel, *args):

""" Send a message to a channel """

buf = pickle.dumps(args)

value = socket.htonl(len(buf))

size = struct.pack("L",value)

channel.send(size)

channel.send(buf)

def receive(channel):

""" Receive a message from a channel """

size = struct.calcsize("L")

size = channel.recv(size)

try:

size = socket.ntohl(struct.unpack("L", size)[0])

except struct.error as e:

return ''

buf = ""

while len(buf) < size:

buf = channel.recv(size - len(buf))

return pickle.loads(buf)[0]The following are some screenshots of the server running and two clients that are connected to each other via the chat server:

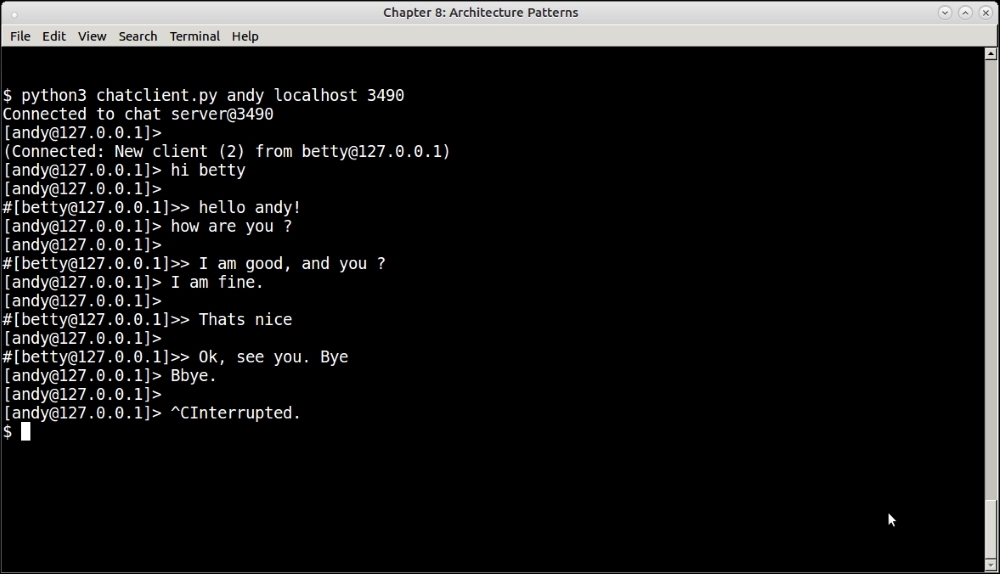

Here is the screenshot of client #1, named andy, connected to the chat server:

Chat session of chat client #1 (client name: andy)

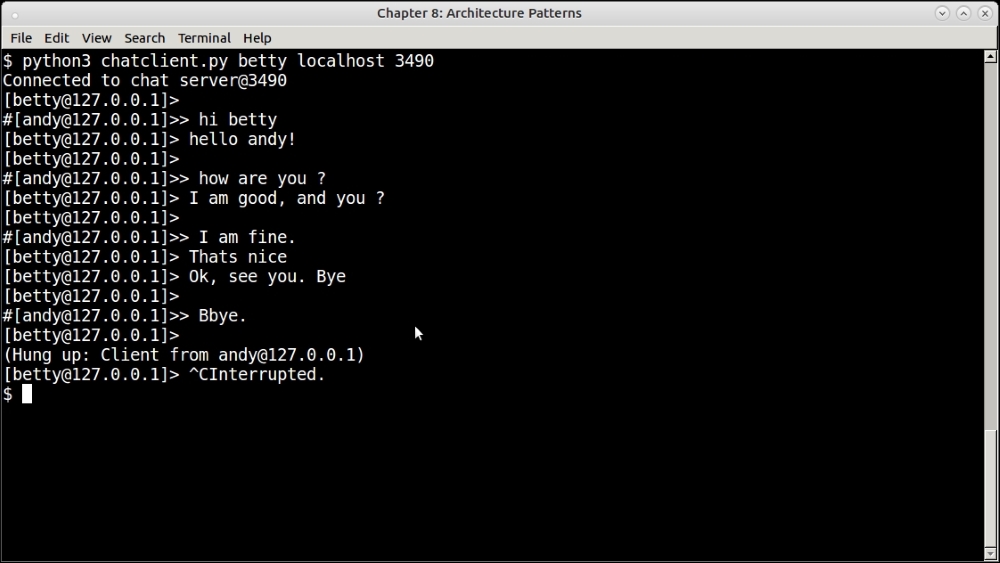

Similarly, here is a client named betty who is connected to the chat server and is talking to andy:

Chat session of chat client #2 (client name: betty)

Some interesting points of the program are as follows:

- See how the clients are able to see each other's messages. This happens because the server sends the data sent by one client to all the other connected clients. Our chat server prefixes the messages with a hash (

#) to indicate that this message is from another client. - See how the server sends connection and disconnection information of a client to all other clients. This informs the clients when another client is connected to or disconnected from the session.

- The server echoes messages when a client disconnects saying that the client hung up.

Note

The preceding chat server and client example is a minor variation of the author's own Python recipe in the ASPN Cookbook at https://code.activestate.com/recipes/531824.

The simple select-based multiplexing is taken to the next level by libraries such as Twisted, Eventlet, and Gevent in order to build systems that provide high-level event-based programming routines to the programmer, typically based on a core event loop very similar to the loop of our chat server example.

We will discuss the architecture of these frameworks in the following sections.

The example we saw in the previous section uses the technique of asynchronous events as we saw in the chapter on concurrency. This is different from true concurrent or parallel programming.

Event programming libraries also work on the technique of asynchronous events. There is only a single thread of execution in which tasks are interleaved one after another based on the events received.

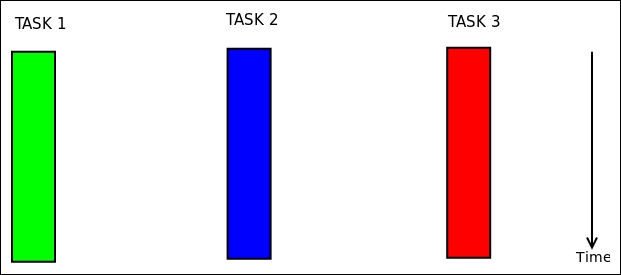

In the following diagram, consider a truly parallel execution of three tasks by three threads or processes:

Parallel execution of three tasks using three threads

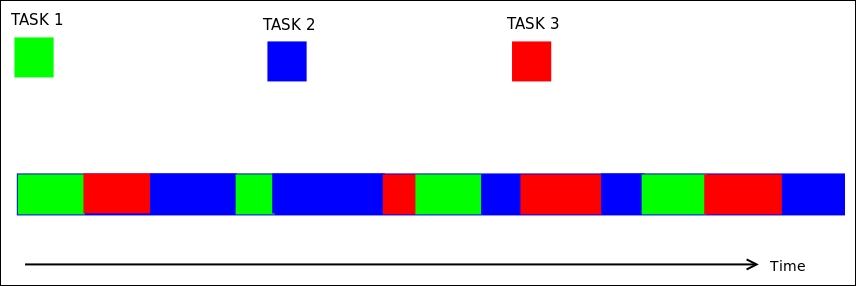

Contrast this with what happens when the tasks are executed via event-driven programming as depicted in the following diagram:

Asynchronous execution of three tasks in a single thread

In the asynchronous model, there is only one single thread of execution with tasks executing in an interleaved fashion. Each task gets its own slot of processing time in the event loop of the asynchronous processing server, but only one task executes at a given time. Tasks yield control back to the loop so that it can schedule a different task in the next time slice from the task that is being executed currently. As we have seen in Chapter 5, Writing Applications that Scale, this is a kind of cooperative multitasking.

Twisted is an event-driven networking engine with support for multiple protocols, such as DNS, SMTP, POP3, IMAP, and so on. It also comes with support for writing SSH clients and servers, and to build messaging and IRC clients and servers.

Twisted also provides a set of patterns (styles) to write common servers and clients, such as web server/client (HTTP), publish/subscribe patterns, messaging clients and servers (SOAP/XML-RPC), and others.

It uses the Reactor design pattern, which multiplexes and dispatches events from multiple sources to their event handlers in a single thread.

It receives messages, requests, and connections coming from multiple concurrent clients, and processes these posts sequentially using event handlers without requiring concurrent threads or processes.

The reactor pseudo-code looks, approximately, as follows:

while True:

timeout = time_until_next_timed_event()

events = wait_for_events(timeout)

events += timed_events_until(now())

for event in events:

event.process()Twisted uses callbacks to call event handlers as and when an event happens. To handle a specific event, a callback is registered for that event. Callbacks can be used for regular processing, and also for managing exceptions (errbacks).

Like the asyncio module, Twisted uses an object such as futures in order to wrap the results of a task execution, whose actual results are still not available. In Twisted, these objects are called Deferreds.

Deferred objects have a pair of callback chains: one for processing results (callbacks) and one for managing errors (errbacks). When the result of an execution is obtained, a Deferred object is created, and its callbacks and/or errbacks are called in the order in which they were added.

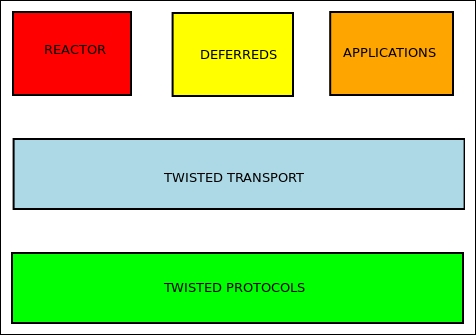

Here is an architecture diagram of Twisted, showing the high-level components:

Twisted—Core Components

The following is a simple example of a web HTTP client using Twisted, fetching a given URL and saving its contents to a specific filename:

# twisted_fetch_url.py

from twisted.internet import reactor

from twisted.web.client import getPage

import sys

def save_page(page, filename='content.html'):

print type(page)

open(filename,'w').write(page)

print 'Length of data',len(page)

print 'Data saved to',filename

def handle_error(error):

print error

def finish_processing(value):

print "Shutting down..."

reactor.stop()

if __name__ == "__main__":

url = sys.argv[1]

deferred = getPage(url)

deferred.addCallbacks(save_page, handle_error)

deferred.addBoth(finish_processing)

reactor.run()As you can see in the preceding code, the getPage method returns a deferred, and not the data of the URL. To the deferred, we add two callbacks: one for processing the data (the save_page function) and another for handling errors (the handle_error function). The addBoth method of the deferred adds a single function as both callback and errback.

The event processing is started by running the reactor. In the finish_processing callback, which is called at the end, the reactor is stopped. Since event handlers are called in the order that they are added, this function will be called only at the very end.

When the reactor is run, the following events happen:

- The page is fetched and the deferred is created.

- The callbacks are called in order on the deferred. First the

save_pagefunction is called, which saves contents of the page to thecontent.htmlfile. Then ahandle_errorevent handler is called, which prints any error string. - Finally,

finish_processingis called, which stops the reactor, and the event processing ends, exiting the program. - When you run the code, you will see that the following output is produced:

$ python2 twisted_fetch_url.py http://www.google.com Length of data 13280 Data saved to content.html Shutting down...

Let's now see how we can write a simple chat server in Twisted on lines similar to our chat server using the select module.

In Twisted, servers are built by implementing protocols and protocol factories. A protocol class typically inherits from the Twisted Protocol class.

A factory is nothing but a class that serves as a factory pattern for protocol objects.

Using this, here is our chat server using Twisted:

from twisted.internet import protocol, reactor

class Chat(protocol.Protocol):

""" Chat protocol """

transports = {}

peers = {}

def connectionMade(self):

self._peer = self.transport.getPeer()

print 'Connected',self._peer

def connectionLost(self, reason):

self._peer = self.transport.getPeer()

# Find out and inform other clients

user = self.peers.get((self._peer.host, self._peer.port))

if user != None:

self.broadcast('(User %s disconnected)

' % user, user)

print 'User %s disconnected from %s' % (user, self._peer)

def broadcast(self, msg, user):

""" Broadcast chat message to all connected users except 'user' """

for key in self.transports.keys():

if key != user:

if msg != "<handshake>":

self.transports[key].write('#[' + user + "]>>> " + msg)

else:

# Inform other clients of connection

self.transports[key].write('(User %s connected from %s)

' % (user, self._peer))

def dataReceived(self, data):

""" Callback when data is ready to be read from the socket """

user, msg = data.split(":")

print "Got data=>",msg,"from",user

self.transports[user] = self.transport

# Make an entry in the peers dictionary

self.peers[(self._peer.host, self._peer.port)] = user

self.broadcast(msg, user)

class ChatFactory(protocol.Factory):

""" Chat protocol factory """

def buildProtocol(self, addr):

return Chat()

if __name__ == "__main__":

reactor.listenTCP(3490, ChatFactory())

reactor.run()Our chat server is a bit more sophisticated than the one before as it performs the following additional steps:

- It has a separate handshake protocol using the special

<handshake>message. - When a client connects, it is broadcast to other clients, informing them of the client's name and connection details.

- When a client disconnects, other clients are informed about this.

The chat client also uses Twisted and uses two protocols—namely a ChatClientProtocol for communication with the server and a StdioClientProtocol for reading data from standard input and echoing data received from the server to the standard output.

The latter protocol also connects the former one to its input, so that any data that is received on the standard input is sent to the server as a chat message.

Take a look at the following code:

import sys

import socket

from twisted.internet import stdio, reactor, protocol

class ChatProtocol(protocol.Protocol):

""" Base protocol for chat """

def __init__(self, client):

self.output = None

# Client name: E.g: andy

self.client = client

self.prompt='[' + '@'.join((self.client, socket.gethostname().split('.')[0])) + ']> '

def input_prompt(self):

""" The input prefix for client """

sys.stdout.write(self.prompt)

sys.stdout.flush()

def dataReceived(self, data):

self.processData(data)

class ChatClientProtocol(ChatProtocol):

""" Chat client protocol """

def connectionMade(self):

print 'Connection made'

self.output.write(self.client + ":<handshake>")

def processData(self, data):

""" Process data received """

if not len(data.strip()):

return

self.input_prompt()

if self.output:

# Send data in this form to server

self.output.write(self.client + ":" + data)

class StdioClientProtocol(ChatProtocol):

""" Protocol which reads data from input and echoes

data to standard output """

def connectionMade(self):

# Create chat client protocol

chat = ChatClientProtocol(client=sys.argv[1])

chat.output = self.transport

# Create stdio wrapper

stdio_wrapper = stdio.StandardIO(chat)

# Connect to output

self.output = stdio_wrapper

print "Connected to server"

self.input_prompt()

def input_prompt(self):

# Since the output is directly connected

# to stdout, use that to write.

self.output.write(self.prompt)

def processData(self, data):

""" Process data received """

if self.output:

self.output.write('

' + data)

self.input_prompt()

class StdioClientFactory(protocol.ClientFactory):

def buildProtocol(self, addr):

return StdioClientProtocol(sys.argv[1])

def main():

reactor.connectTCP("localhost", 3490, StdioClientFactory())

reactor.run()

if __name__ == '__main__':

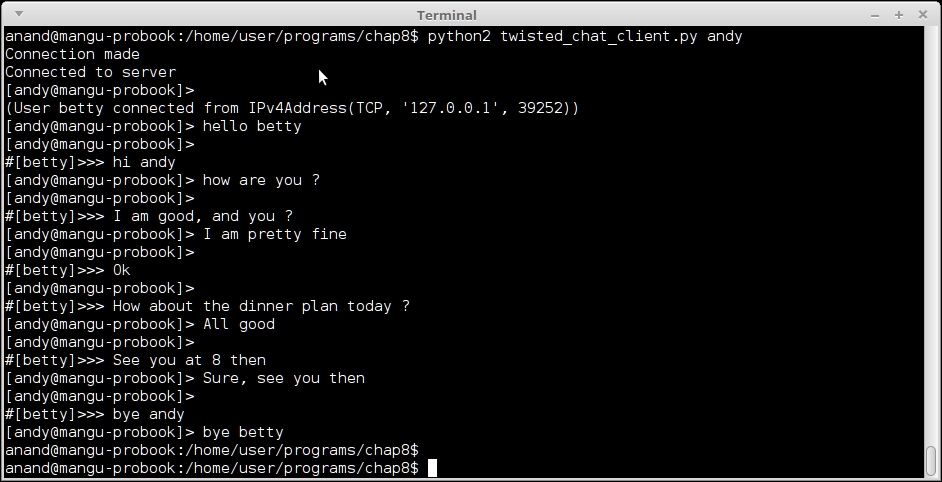

main()Here are some screenshots of the two clients andy and betty communicating using this chat server and client:

Chat client using Twisted chat server—session for client #1 (andy)

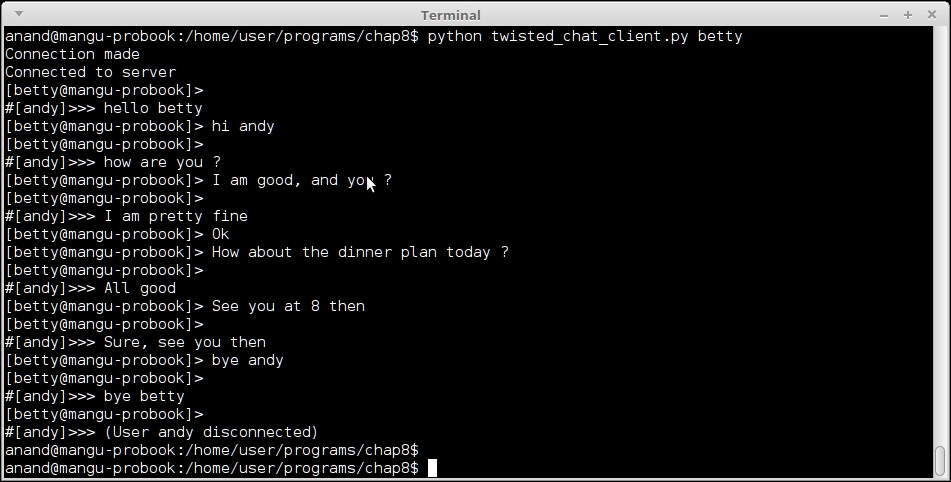

Here is the second session, for the client betty:

Chat client using Twisted chat server—session for client #2 (betty)

You can follow the flow of the conversation by alternately looking at the screenshots.

Note the connection and disconnection messages are sent by the server when user betty connects and user andy disconnects respectively.

Eventlet is another well-known networking library in the Python world that allows one to write event-driven programs using the same concept of asynchronous execution.

Eventlet uses co-routines for this purpose with the help of a set of so-called green threads, which are lightweight user-space threads that perform cooperative multitasking.

Eventlet uses an abstraction over a set of green threads, the Greenpool class, in order to perform its tasks.

The Greenpool class runs a predefined set of Greenpool threads (default is 1000), and provides ways to map functions and callables to the threads in different ways.

Here is the multiuser chat server rewritten using Eventlet:

# eventlet_chat.py

import eventlet

from eventlet.green import socket

participants = set()

def new_chat_channel(conn):

""" New chat channel for a given connection """

data = conn.recv(1024)

user = ''

while data:

print("Chat:", data.strip())

for p in participants:

try:

if p is not conn:

data = data.decode('utf-8')

user, msg = data.split(':')

if msg != '<handshake>':

data_s = '

#[' + user + ']>>> says ' + msg

else:

data_s = '(User %s connected)

' % user

p.send(bytearray(data_s, 'utf-8'))

except socket.error as e:

# ignore broken pipes, they just mean the participant

# closed its connection already

if e[0] != 32:

raise

data = conn.recv(1024)

participants.remove(conn)

print("Participant %s left chat." % user)

if __name__ == "__main__":

port = 3490

try:

print("ChatServer starting up on port", port)

server = eventlet.listen(('0.0.0.0', port))

while True:

new_connection, address = server.accept()

print("Participant joined chat.")

participants.add(new_connection)

print(eventlet.spawn(new_chat_channel,

new_connection))

except (KeyboardInterrupt, SystemExit):

print("ChatServer exiting.")The Eventlet library internally uses greenlets, a package that provides green threads on Python runtime. We will see greenlet and a related library, Gevent, in the following section.

Greenlet is a package that provides a version of green or microthreads on top of the Python interpreter. It is inspired by Stackless, a version of CPython that supports microthreads called stacklets. However, greenlets are able to run on the standard CPython runtime.

Gevent is a Python networking library providing a high-level synchronous API on top of libev, the event library written in C.

Gevent is inspired by gevent, but it features a more consistent API and better performance.

Like Eventlet, gevent does a lot of monkey patching on system libraries to provide support for cooperative multitasking. For example, gevent comes with its own sockets, just like Eventlet does.

Unlike Eventlet, gevent also requires explicit monkey patching to be done by the programmer. It provides a method to do this on the module itself.

Without further ado, let's look at the multiuser chat server using gevent:

# gevent_chat_server.py

import gevent

from gevent import monkey

from gevent import socket

from gevent.server import StreamServer

monkey.patch_all()

participants = set()

def new_chat_channel(conn, address):

""" New chat channel for a given connection """

participants.add(conn)

data = conn.recv(1024)

user = ''

while data:

print("Chat:", data.strip())

for p in participants:

try:

if p is not conn:

data = data.decode('utf-8')

user, msg = data.split(':')

if msg != '<handshake>':

data_s = '

#[' + user + ']>>> says ' + msg

else:

data_s = '(User %s connected)

' % user

p.send(bytearray(data_s, 'utf-8'))

except socket.error as e:

# ignore broken pipes, they just mean the participant

# closed its connection already

if e[0] != 32:

raise

data = conn.recv(1024)

participants.remove(conn)

print("Participant %s left chat." % user)

if __name__ == "__main__":

port = 3490

try:

print("ChatServer starting up on port", port)

server = StreamServer(('0.0.0.0', port), new_chat_channel)

server.serve_forever()

except (KeyboardInterrupt, SystemExit):

print("ChatServer exiting.")The code for the gevent-based chat server is almost the same as the one using Eventlet. The reason for this is that they work in very similar ways, by handling control to a callback function when a new connection is made. In both cases the callback function is named new_chat_channel, which has the same functionality and hence very similar code.

The differences between the two are as follows:

- gevent provides its own TCP server class—

StreamingServer–so we use that instead of listening on the module directly. - In the gevent server, for every connection the

new_chat_channelhandler is invoked, hence the participant set is managed there. - Since the gevent server has its own event loop, there is no need to create a while loop for listening for incoming connections as we had to do with Eventlet.

This example works exactly the same as the previous ones and works with the Twisted chat client.