In the previous chapter, we learned what the Seam Framework is, and what it offers to Java developers. In this chapter, we are going to start learning how to develop applications using Seam, and we will see some of the features we had discussed previously. In this chapter, we will learn the basic structure of a Seam application. We will see in practice how Seam Injection and Outjection work, and we will learn more about Seam components. We will also see exactly how Seam bridges the gap between the Web tier (using Java Server Faces) and the Server tier (using Enterprise Java Beans).

Note

As most enterprise Java developers are probably familiar with JSF and JSP, we will be using this as the view technology for our sample applications, until we have a solid understanding of Seam. In Chapter 4, we will introduce Facelets as the recommended view technology for Seam-based applications.

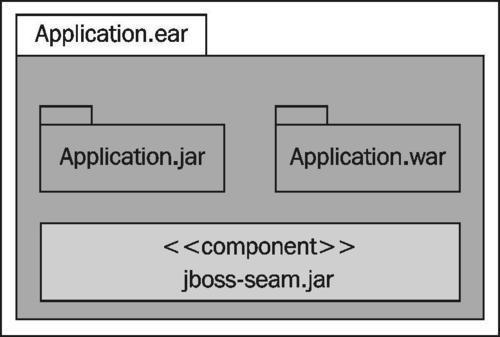

In a standard Java EE application, Enterprise Application Resource (EAR) files contain one or more Web Application Resource (WAR) files and one or more sets of Java Archive (JAR) files containing Enterprise JavaBeans (EJB) functionality. Seam applications are generally deployed in exactly the same manner as depicted in the following diagram. It is possible to deploy Seam onto a servlet-only container (for example, Tomcat) and use POJOs as the server-side Seam components. However, in this situation, we don't get any of the benefits that EJBs provide, such as security, transaction handling, management, or pooling.

Within Seam, components are simple POJOs. There is no need to implement any interfaces or derive classes from a Seam-specific base class to make Seam components classes. For example, a Seam component could be:

Seam components are defined by adding the @Name annotation to a class definition. The @Name annotation takes a single parameter to define the name of the Seam component. The following example shows how a stateless Session Bean is defined as a Seam component called calcAction.

package com.davidsalter.seamcalculator;

@Stateless

@Name("calcAction")

public class CalcAction implements Calc {

...

}

When a Seam application is deployed to JBoss, the log output at startup lists what Seam components are deployed, and what type they are. This can be useful for diagnostic purposes, to ensure that your components are deployed correctly. Output similar to the following will be shown in the JBoss console log when the CalcAction class is deployed:

21:24:24,097 INFO [Initialization] Installing components...

21:24:24,121 INFO [Component] Component: calcAction, scope:

STATELESS, type: STATELESS_SESSION_BEAN, class: com.davidsalter.

seamcalculator.CalcAction, JNDI: SeamCalculator/CalcAction/local

One of the benefits of using Seam is that it acts as the "glue" between the web technology and the server-side technology. By this we mean that the Seam Framework allows us to use enterprise beans (for example, Session Beans) directly within the Web tier without having to use Data Transfer Object (DTO) patterns and without worrying about exposing server-side functionality on the client.

Additionally, if we are using Session Beans for our server-side functionality, we don't really have to develop an additional layer of JSF backing beans, which are essentially acting as another layer between our web page and our application logic.

In order to fully understand the benefits of Seam, we need to first describe what we mean by Injection and Outjection.

Injection is the process of the framework setting component values before an object is created. With injection, the framework is responsible for setting components (or injecting them) within other components. Typically, Injection can be used to allow component values to be passed from the web page into Seam components.

Outjection works in the opposite direction to Injection. With Outjection, components are responsible for setting component values back into the framework. Typically, Outjection is used for setting component values back into the Seam Framework, and these values can then be referenced via JSF Expression Language (EL) within JSF pages. This means that Outjection is typically used to allow data values to be passed from Seam components into web pages.

Seam allows components to be injected into different Seam components by using the @In annotation and allows us to outject them by using the @Out annotation. For example, if we have some JSF code that allows us to enter details on a web form, we may use an <h:inputText …/> tag such as this:

<h:inputText value="#{calculator.value1}" required="true"/>

The Seam component calculator could then be injected into a Seam component using the @In annotation as follows:

@In private Calculator calculator;

With Seam, all of the default values on annotations are the most likely ones to be used. In the preceding example therefore, Seam will look up a component called calculator and inject that into the calculator variable. If we wanted Seam to inject a variable with a different name to the variable that it is being injected into, we can adorn the @In annotation with the value parameter.

@In (value="myCalculator") private Calculator calculator;

In this example, Seam will look up a component called myCalculator and inject it into the variable calculator.

Similarly, if we want to outject a variable from a Seam component into a JSF page, we would use the @Out annotation.

@Out private Calculator calculator;

The outjected calculator object could then be used in a JSF page in the following manner:

<h:outputText value="#{calculator.answer}"/>

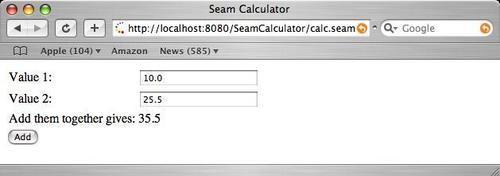

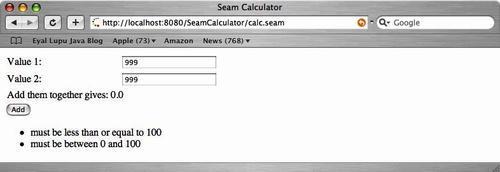

To see these concepts in action, and to gain an understanding of how Seam components are used instead of JSF backing beans, let us look at a simple calculator web application. This simple application allows us to enter two numbers on a web page. Clicking the Add button on the web page will cause the sum of the numbers to be displayed.

This basic application will give us an understanding of the layout of a Seam application and how we can inject and outject components between the business layer and the view. The application functionality is shown in the following screenshot.

Note

The sample code for this application can be downloaded from the Packt web site, at http://www.packtpub.com/support.

For this sample application, we have a single JSF page that is responsible for:

Reading two numeric values from the user

Invoking business logic to add the numbers together

Displaying the results of adding the numbers together

<%@ taglib uri="http://java.sun.com/jsf/html" prefix="h" %>

<%@ taglib uri="http://java.sun.com/jsf/core" prefix="f" %>

<html>

<head>

<title>Seam Calculator</title>

</head>

<body>

<f:view>

<h:form>

<h:panelGrid columns="2">

Value 1: <h:inputText value="#{calculator. value1}" />

Value 2: <h:inputText value="#{calculator. value2}" />

Add them together gives: <h:outputText value=" #{calculator.answer} "/>

</h:panelGrid>

<h:commandButton value="Add" action= "#{calcAction.calculate}"/>

</h:form>

</f:view>

</body>

</html>

We can see that there is nothing Seam-specific in this JSF page. However, we are binding two inputText areas, one outputText area, and a button action to Seam components by using standard JSF Expression Language.

|

JSF EL |

Seam Binding |

|---|---|

|

|

This is bound to the member variable |

|

|

This is bound to the member variable |

|

|

This is bound to the member variable |

|

|

This will invoke the method |

Our business logic for this sample application is performed in a simple POJO class called Calculator.java.

package com.davidsalter.seamcalculator; import java.io.Serializable; import org.jboss.seam.annotations.Name; @Name("calculator") public class Calculator { private double value1; private double value2; private double answer; public double getValue1() { return value1; } public void setValue1(double value1) { this.value1 = value1; } public double getValue2() { return value2; } public void setValue2(double value2) { this.value2 = value2; } public double getAnswer() { return answer; } public void add() { this.answer = value1 + value2; } }

This class is decorated with the @Name("calculator") annotation, which causes it to be registered to Seam with the name, "calculator". The @Name annotation causes this object to be registered as a Seam component that can subsequently be used within other Seam components via Injection or Outjection by using the @In and @Out annotations.

Finally, we need to have a class that is acting as a backing bean for the JSF page that allows us to invoke our business logic. In this example, we are using a Stateless Session Bean. The Session Bean and its local interface are as follows.

In the Java EE 5 specification, a Stateless Session Bean is used to represent a single application client's communication with an application server. A Stateless Session Bean, as its name suggests, contains no state information; so they are typically used as transaction façades. A Façade is a popular design pattern, which defines how simplified access to a system can be provided. For more information about the Façade pattern, check out the following link:

http://java.sun.com/blueprints/corej2eepatterns/Patterns/SessionFacade.html

Defining a Stateless Session Bean using Java EE 5 technologies requires an interface and an implementation class to be defined. The interface defines all of the methods that are available to clients of the Session Bean, whereas the implementation class contains a concrete implementation of the interface. In Java EE 5, a Session Bean interface is annotated with either the @Local or @Remote or both annotations. An @Local interface is used when a Session Bean is to be accessed locally within the same JVM as its client (for example, a web page running within an application server). An @Remote interface is used when a Session Bean's clients are remote to the application server that is running within a different JVM as the application server.

There are many books that cover Stateless Session Beans and EJB 3 in depth, such as EJB 3 Developer's Guide by Michael Sikora, published by Packt Publishing. For more information on this book, check out the following link:

http://www.packtpub.com/developer-guide-for-ejb3

In the following code, we are registering our CalcAction class with Seam under the name calcAction. We are also Injecting and Outjecting the calculator variable so that we can use it both to retrieve values from our JSF form and pass them back to the form.

package com.davidsalter.seamcalculator; import javax.ejb.Stateless; import org.jboss.seam.annotations.In; import org.jboss.seam.annotations.Out; import org.jboss.seam.annotations.Name; @Stateless @Name("calcAction") public class CalcAction implements Calc { @In @Out private Calculator calculator; public String calculate() { calculator.add(); return ""; } } package com.davidsalter.seamcalculator; import javax.ejb.Local; @Local public interface Calc { public String calculate(); }

That's all the code we need to write for our sample application. If we review this code, we can see several key points where Seam has made our application development easier:

All of the code that we have developed has been written as POJOs, which will make unit testing a lot easier.

We haven't extended or implemented any special Seam interfaces.

We've not had to define any JSF backing beans explicitly in XML. We're using Java EE Session Beans to manage all of the business logic and web-tier/business-tier integration.

We've not used any DTO objects to transfer data between the web and the business tiers. We're using a Seam component that contains both state and behavior.

If you are familiar with JSF, you can probably see that adding Seam into a fairly standard JSF application has already made our development simpler.

Finally, to enable Seam to correctly find our Seam components and deploy them correctly to the application server, we need to create an empty file called seam.properties and place it within the root of the classpath of the EJB JAR file. Because this file is empty, we will not discuss it further here. We will, however, see the location of this file in the section Application layout, later in this chapter.

To deploy the application as a WAR file embedded inside an EAR file, we need to write some deployment descriptors.

To deploy a WAR file with Seam, we need to define several files within the WEB-INF directory of the archive:

web.xmlfaces-config.xmlcomponents.xml

First let's take a look at the web.xml file. This is a fairly standard file that specifies the SeamListener class, which aids internal Seam initialization and cleanup. This file also specifies that all pages with the extension .seam will be run as JSF pages.

<?xml version="1.0" ?> <web-app xmlns="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee/web-app_2_5.xsd" version="2.5"> <listener> <listener-class>org.jboss.seam.servlet. SeamListener</listener-class> </listener> <context-param> <param-name>javax.faces.DEFAULT_SUFFIX</param-name> <param-value>.jsp</param-value> </context-param> <servlet> <servlet-name>Faces Servlet</servlet-name> <servlet-class>javax.faces.webapp.FacesServlet</servlet-class> <load-on-startup>1</load-on-startup> </servlet> <servlet-mapping> <servlet-name>Faces Servlet</servlet-name> <url-pattern>*.seam</url-pattern> </servlet-mapping> </web-app>

The faces-config.xml file allows Seam to be integrated into the JSF page life cycle, by adding the org.jboss.seam.jsf.SeamPhaseListener into the life cycle events chain.

<?xml version='1.0' encoding='UTF-8'?> <faces-config version="1.2" xmlns="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee/web-facesconfig_1_2.xsd"> <lifecycle> <phase-listener>org.jboss.seam.jsf. SeamPhaseListener</phase-listener> </lifecycle> </faces-config>

Finally, the components.xml file allows any Seam components that we may be using to be configured. In our sample application, the only configuration that we are performing is specifying the JNDI pattern to allow EJB components to be looked up by Seam.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <components xmlns="http://jboss.com/products/seam/components" xmlns:core="http://jboss.com/products/seam/core" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://jboss.com/products/seam/core http://jboss.com/products/seam/core-2.1.xsd http://jboss.com/products/seam/components http://jboss.com/products/seam/components-2.1.xsd"> <core:init jndi-pattern="@jndiPattern@"/> </components>

In the later chapters, we will look in detail at the components.xml file, as it is in this file that we will specify Seam-specific information such as security and web page viewing options.

To deploy an EAR file with Seam on JBoss, we need to define several deployment descriptors within the META-INF directory of the archive:

application.xmlejb-jar.xmljboss-app.xml

The application.xml file allows us to define the modules that are to be deployed to JBoss. In this file, we need to specify the WAR file for our application and the JAR file that contains our Session Beans. We must also include a reference to the jboss-seam.jar file.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <application xmlns="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee/application_5.xsd" version="5"> <display-name>SeamCalculator</display-name> <module> <web> <web-uri>SeamCalculator.war</web-uri> <context-root>/SeamCalculator</context-root> </web> </module> <module> <ejb>SeamCalculator.jar</ejb> </module> <module> <ejb>jboss-seam.jar</ejb> </module> </application>

In the ejb-jar.xml file, we must attach the org.jboss.seam.ejb.SeamInterceptor class onto all our EJBs.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <ejb-jar xmlns="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee http://java.sun.com/xml/ns/javaee/ejb-jar_3_0.xsd" version="3.0"> <interceptors> <interceptor> <interceptor-class>org.jboss.seam.ejb. SeamInterceptor</interceptor-class> </interceptor> </interceptors> <assembly-descriptor> <interceptor-binding> <ejb-name>*</ejb-name> <interceptor-class>org.jboss.seam.ejb. SeamInterceptor</interceptor-class> </interceptor-binding> </assembly-descriptor> </ejb-jar>

Finally, we can specify a class loader for our Seam application in jboss-app.xml so that there are no conflicts between the classes deployed to the JBoss Application Server and the ones deployed to our application.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <!DOCTYPE jboss-app PUBLIC "-//JBoss//DTD J2EE Application 5.0//EN" "http://www.jboss.org/j2ee/dtd/jboss-app_5_0.dtd"> <jboss-app> <loader-repository> seam.jboss.org:loader=SeamCalculator </loader-repository> </jboss-app>

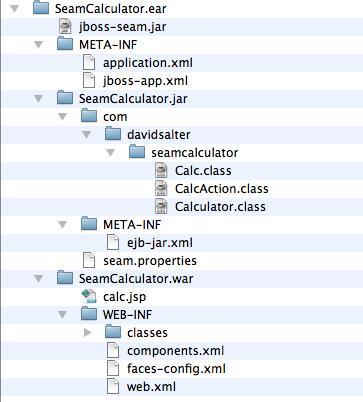

Before we deploy and run the test application, let's take a look at the layout of our sample application. As you can see in the following screenshot, the layout of the application follows the standard layout of a Java EE application. The application is deployed as a single EAR file. Within the EAR file, we have the Seam JAR file, our EJB JAR file, and our web application EAR file. This is the standard layout that all of our Seam applications are going to follow.

Now that we have looked at the code for both the application and the deployment descriptors, let's build the application and test it before deploying it to the JBoss Application Server.

It is traditionally quite difficult to perform unit tests on enterprise applications because of their nature. Without using Seam, the testing of web pages and Java EE resources (for example, Session Beans) requires that the application be deployed to an application server. This makes testing more difficult and can vastly increase the development time of applications.

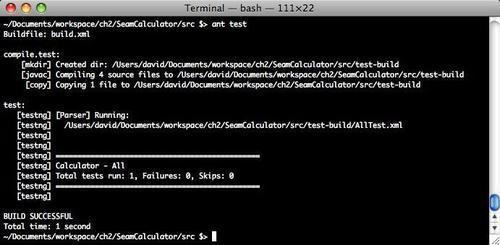

However, Seam offers great support for testing applications outside the application server, including support for testing web pages. The standard testing framework used with Seam is TestNG (http://www.testng.org). However, there are some Seam-specific extensions that make testing easier. We'll cover the full testing of Seam applications in a later chapter, but for now, let's see how to test the business logic of our application, and indeed any POJOs that we can write, by using a standard TestNG unit test.

TestNG uses Java 5 annotations to allow methods to be declared as tests. To declare a method as a unit test, we simply need to adorn the method with the @Test annotation. Within a test, we can then assert different conditions to test whether our code is working as expected.

We could write a simple test for our calculator application as follows:

package com.davidsalter.seamcalculator.test;

import com.davidsalter.seamcalculator.Calculator;

import org.testng.annotations.Test;

public class CalculatorTest {

private static double tolerance = 0.001;

@Test

public void testAdd() throws Exception {

Calculator testCalculator = new Calculator();

testCalculator.setValue1(10.0);

testCalculator.setValue2(20.0);

testCalculator.add();

assert (testCalculator.getAnswer() - 30.0 < tolerance);

}

}

This test simply instantiates an instance of the Calculator class, sets up some test data, and invokes the add() method before asserting that the answer is as expected.

Before we can run this unit test, we must also define an XML file that details which tests to run. For Seam tests, this file is typically called AllTests.xml. The contents of this file, for our sample application, are as follows:

<!DOCTYPE suite SYSTEM "http://testng.org/testng-1.0.dtd" > <suite name="Calculator - All" verbose="1"> <test name="Calculator"> <packages> <package name="com.davidsalter.seamcalculator.test"/> </packages> </test> </suite>

Finally, before we can build and test the application, we need to copy a few JAR files from the Seam installation into our build path. To build and test a basic Seam application, we need to build against some of the Seam JAR files:

All of these JAR files can be found in the <jboss_seam>/lib directory, where <jboss_seam> is the directory that you have installed Seam into. If you have taken the sample application from the download bundle for this chapter, copy these files into the /lib directory of the project.

To test the sample application, we need to execute the Test target in the ant build file, as shown in the following screenshot.

Executing the tests should show that one test has been run, and that there were no failures and no skipped tests. Assuming that the test was completed successfully, we can be fairly confident that our application will run correctly when built and deployed to the application server.

In the previous section, we saw how to perform a basic unit test to verify that the application logic is functioning correctly. Once all of our application's unit tests succeed (one of them in this case), we can build the application and deploy it to JBoss.

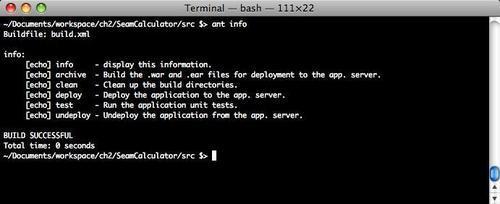

To build and deploy the application, we use the ant script again. The ant script provides several different targets, allowing the project to be compiled, deployed, and archived into an EAR file. Executing the Info target provides the following help screen, which shows which targets are available.

|

Ant target |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

The

|

|

|

The |

|

|

The |

|

|

The |

|

|

The |

|

|

The |

Note

Within the JBoss Application Server, applications can be hot deployed by copying them into the <jboss_home>/server/default/deploy directory. Similarly, to undeploy an application, just delete it from the <jboss_home>/server/default/deploy directory.

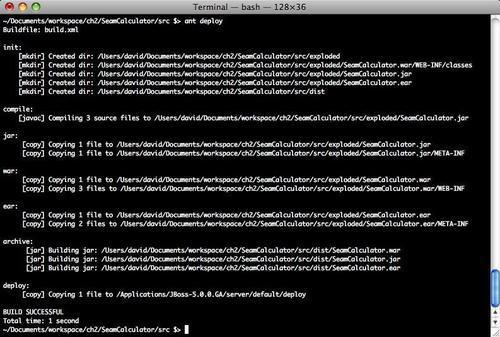

To build and deploy the application to JBoss, execute the deploy task.

If the JBoss Application Server is running, we should see some log output appear on the JBoss console, ending with a line saying that the application has been deployed successfully, as shown below:

[EARDeployer] Started J2EE application: file:/Applications/ jboss-5.0.0.GA/server/default/deploy/SeamCalculator.ear

Note

If we don't see the application deployed to the JBoss Application Server and there were no errors during compilation, check the value of the jboss.home property within the build.properties file.

Once we see the preceding line on the JBoss console, it means that JBoss has successfully deployed the application and we can test it out.

To run the application, visit the web site http://localhost:8080/SeamCalculator/calc.seam and try adding some numbers together to prove that the application is functioning as expected.

So far we've looked at Seam and learned how Seam can act as JSF backing beans and how it can act as the glue between our server-tier Session Beans and our web-tier JSF pages. Unfortunately, though, users could easily break our sample application by entering invalid data (for example, entering blank values or non-numeric values into the edit boxes). Seam provides validation tools to help us to make our application more robust and provide feedback to our users. Let's look at these tools now.

In order to perform consistent data validation, we would ideally want to perform all data validation within our data model. We want to perform data validation in our data model so that we can then keep all of the validation code in one place, which should then make it easier to keep it up-to-date if we ever change our minds about allowable data values.

Seam makes extensive use of the Hibernate validation tools to perform validation of our domain model. The Hibernate validation tools grew from the Hibernate project (http://www.hibernate.org) to allow the validation of entities before they are persisted to the database. To use the Hibernate validation tools in an application, we need to add hibernate-validator.jar into the application's class path, after which we can use annotations to define the validation that we want to use for our data model. We'll discuss data validation and the Hibernate validator further in Chapter 7, when we talk about persisting objects to the database. But for now, let's look at a few validations that we can add to our sample Seam Calculator application.

In order to implement data validation with Seam, we need to apply annotations either to the member variables in a class or to the getter of the member variables. It's good practice to always apply these annotations to the same place in a class. Hence, throughout this book, we will always apply our annotation to the getter methods within classes.

In our sample application, we are allowing numeric values to be entered via edit boxes on a JSF form. To perform data validation against these inputs, there are a few annotations that can help us.

|

Annotation |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

The

|

|

|

The

|

|

|

The

|

At this point, you may be wondering why we need to have an @Range validator, when by combining the @Min and @Max validators, we can get a similar effect. If you want a different error message to be displayed when a variable is set above its maximum value as compared to the error message that is displayed when it is set below its minimum value, then the @Min and @Max annotations should be used. If you are happy with the same error message being displayed when a variable is set outside its minimum or maximum values, then the @Range validator should be used. Effectively, the @Min and @Max validators are providing a finer level of error message provision than the @Range validator.

The following code sample shows how these annotations can be applied to the sample application that we have written so far in this chapter, to add basic data validation to our user inputs.

package com.davidsalter.seamcalculator; import java.io.Serializable; import org.jboss.seam.annotations.Name; import org.jboss.seam.faces.FacesMessages; import org.hibernate.validator.Max; import org.hibernate.validator.Min; import org.hibernate.validator.Range; @Name("calculator") public class Calculator implements Serializable { private double value1; private double value2; private double answer; @Min(value=0) @Max(value=100) public double getValue1() { return value1; } public void setValue1(double value1) { this.value1 = value1; } @Range(min=0, max=100) public double getValue2() { return value2; } public void setValue2(double value2) { this.value2 = value2; } public double getAnswer() { return answer; } … }

In the previous section, we saw how to add data validation to our source code to stop invalid data from being entered into our domain model. Now that we have reached a level of data validation, we need to provide feedback to the user to inform them of any invalid data that they have entered.

JSF applications have the concept of messages that can be displayed associated with different components. For example, if we have a form asking for a date of birth to be entered, we could display a message next to the entry edit box if an invalid date were entered. JSF maintains a collection of these error messages, and the simplest way of providing feedback to the user is to display a list of all of the error messages that were generated as a part of the previous operation.

In order to obtain error messages within the JSF page, we need to tell JSF which components we want to be validated against the domain model. This is achieved by using the <s:validate/> or <s:validateAll/> tags. These are Seam-specific tags and are not a part of the standard JSF runtime. In order to use these tags, we need to add the following taglib reference to the top of the JSF page.

<%@ taglib uri="http://jboss.com/products/seam/taglib" prefix="s" %>

In order to use this tag library, we need to add a few additional JAR files into the WEB-INF/lib directory of our web application, namely:

jboss-el.jarjboss-seam-ui.jarjsf-api.jarjsf-impl.jar

This tag library allows us to validate all of the components (<s:validateAll/>) within a block of JSF code, or individual components (<s:validate/>) within a JSF page.

To validate all components within a particular scope, wrap them all with the <s:validateAll/> tag as shown here:

<h:form> <s:validateAll> <h:inputText value="…" /> <h:inputText value="…" /> </s:validateAll> </h:form>

To validate individual components, embed the <s:validate/> tag within the component, as shown in the following code fragment.

<h:form> <h:inputText value="…" > <s:validate/> </h:inputText> <h:inputText value="…" > <s:validate/> </h:inputText> </h:form>

After specifying that we wish validation to occur against a specified set of controls, we can display error messages to the user. JSF maintains a collection of errors on a page, which can be displayed in its entirety to a user via the <h:messages/> tag.

It can sometimes be useful to show a list of all of the errors on a page, but it isn't very useful to the user as it is impossible for them to say which error relates to which control on the form. Seam provides some additional support at this point to allow us to specify the formatting of a control to indicate error or warning messages to users.

Seam provides three different JSF facets (<f:facet/>) to allow HTML to be specified both before and after the offending input, along with a CSS style for the HTML. Within these facets, the <s:message/> tag can be used to output the message itself. This tag could be applied either before or after the input box, as per requirements.

|

Facet |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

This facet allows HTML to be displayed before the input that is in error. This HTML could contain either text or images to notify the user that an error has occurred.

|

|

|

This facet allows HTML to be displayed after the input that is in error. This HTML could contain either text or images to notify the user that an error has occurred.

|

|

|

This facet allows the CSS style of the text surrounding the input that is in error to be specified.

|

In order to specify these facets for a particular field, the <s:decorate/> tag must be specified outside the facet scope.

<s:decorate>

<f:facet name="aroundInvalidField">

<s:span styleClass="invalidInput"/>

</f:facet>

<f:facet name="beforeInvalidField">

<f:verbatim>**</f:verbatim>

</f:facet>

<f:facet name="afterInvalidField">

<s:message/>

</f:facet>

<h:inputText value="#{calculator.value1}" required="true" >

<s:validate/>

</h:inputText>

</s:decorate>

In the preceding code snippet, we can see that a CSS style called invalidInput is being applied to any error or warning information that is to be displayed regarding the <inputText/> field. An erroneous input field is being adorned with a double asterisk (**) preceding the edit box, and the error message specific to the inputText field after is displayed in the edit box.

Applying these features to our sample application, the calc.jsp file will appear as follows:

<%@ taglib uri="http://java.sun.com/jsf/html" prefix="h" %>

<%@ taglib uri="http://java.sun.com/jsf/core" prefix="f" %>

<%@ taglib uri="http://jboss.com/products/seam/taglib" prefix="s" %>

<html>

<head>

<title>Seam Calculator</title>

<link href="styles.css" rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" />

</head>

<body>

Seam data validationerrors, displaying<f:view>

<h:form>

<h:panelGrid columns="2">

Value 1:

<s:decorate>

<f:facet name="aroundInvalidField">

<s:span styleClass="invalidInput"/>

</f:facet>

<f:facet name="beforeInvalidField">

<f:verbatim>**</f:verbatim>

</f:facet>

<f:facet name="afterInvalidField">

<s:message/>

</f:facet>

<h:inputText value="#{calculator.value1}" required="true" >

<s:validate/>

</h:inputText>

</s:decorate>

Value 2:

<s:decorate>

<f:facet name="aroundInvalidField">

<s:span styleClass="invalidInput"/>

</f:facet>

<f:facet name="beforeInvalidField">

<f:verbatim>**</f:verbatim>

</f:facet>

<f:facet name="afterInvalidField">

<s:message/>

</f:facet>

<h:inputText value="#{calculator.value2}" required="true">

<s:validate/>

</h:inputText>

</s:decorate>

Adding them together gives:

<h:outputText value="#{calculator.answer}"/>

</h:panelGrid>

<h:commandButton value="Add" action="#{calcAction.calculate}"/>

<h:messages/>

</h:form>

</f:view>

</body>

</html>

To allow validation information to be displayed, we made several changes to this file and to our web application. These changes are listed here:

Adding the Seam UI tag library to the header of the JSF page.

Specifying which objects need to be validated, by using the

<s:validate/>or<s:validateAll/>tags.Defining the three different facets that specify the formatting and output of the error message for each field. These facets must be surrounded by the

<s:decorate/>tag.Adding the Seam and third-party JARs into the

WEB-INF/libdirectory of the web application.

So far, we've only added messages to the JSF messages collection via Hibernate validators that are applied to entities within our domain model. Sometimes, it can be useful to add a message that can be displayed irrespective of any errors or input controls on a form to the messages collection. The JSF messages collection is one of Seam's in-built components and is named org.jboss.seam.faces.facesMessages.

@Name("org.jboss.seam.faces.facesMessages")

This in-built component can easily be accessed within Seam applications by using the FacesMessages().instance() method. For example:

FacesMessages.instance().add("Phew, that was a lot of maths !!");

If we add all of our Hibernate validators to our Calculator.java class, the code will look as follows:

package com.davidsalter.seamcalculator;

import java.io.Serializable;

import org.jboss.seam.annotations.Name;

import org.jboss.seam.faces.FacesMessages;

import org.hibernate.validator.Max;

import org.hibernate.validator.Min;

import org.hibernate.validator.Range;

@Name("calculator")

public class Calculator implements Serializable {

private double value1;

private double value2;

private double answer;

@Min(value=0)

@Max(value=100)

public double getValue1() {

return value1;

}

public void setValue1(double value1) {

this.value1 = value1;

}

@Range(min=0, max=100)

public double getValue2() {

return value2;

}

public void setValue2(double value2) {

this.value2 = value2;

}

public double getAnswer() {

return answer;

}

public void add() {

this.answer = value1 + value2;

//Access the "org.jboss.seam.faces.facesMessages" component and add a message into it.

FacesMessages.instance().add("Phew, that was a lot of maths !!");

}

}

In this code, we have added validators to the input data and then added a custom message into the JSF messages collection, to be displayed when a successful calculation was performed.

In order to build and test the validating Seam calculator, we need to copy the additional JAR files (namely, hibernate-validator.jar, jboss-el.jar, jboss-seam-ui.jar, jsf-api.jar, and jsf-impl.jar) into the /lib directory of the sample project.

Note

A second sample project—Seam Validating Calculator—is available in the code bundle for this chapter.

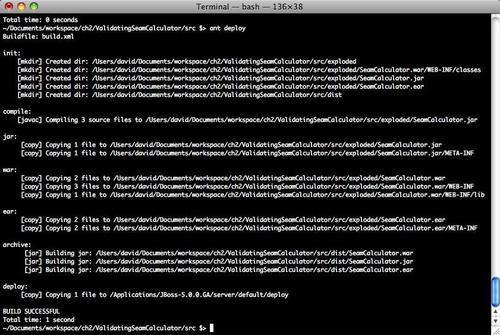

To build and deploy the project onto the JBoss Application Server, we need to execute the deploy ant target.

To view the application in the browser, navigate to http://localhost:8080/SeamCalculator/calc.seam.

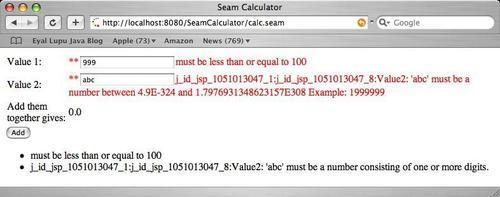

If any invalid data is entered into the web application, this is picked up by the Hibernate validators and displayed on the form, both next to the field containing the error and in a list at the bottom of the page, which shows all of the errors on the page.

In the previous screenshot, you can see that the Hibernate validator has done its job correctly and added an error message informing the user that Value 2 is invalid as abc is not a valid number. While this is technically correct, the error message is very user-unfriendly and would probably result with many unhappy customers! Later on in this book, we will look at how this error message can easily be changed in a localizable fashion so that an appropriate error message can be displayed in different languages for different users. For the moment, the important thing to note is that we have performed validation on user input and provided an error message when the validation fails.

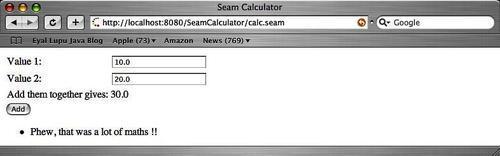

When valid information is entered into the fields and the Add button is clicked, the two inputs are added together and displayed along with a custom error message that was added to the JSF messages collection.

In this chapter, we've taken our first real steps into developing Seam applications. We've looked into Seam components and learned that they are declared with the @Name annotation. We've seen how we can inject and outject Seam components by using the @In and @Out annotations respectively. After learning about Seam components, we wrote a simple Seam application using these concepts, which shows the layout for Seam applications.

In the second half of this chapter, we looked at how to add validation to Seam components and how to display validation errors and special messages on web pages, both around input components and in a list on the page.

In the sample application that we built in this chapter, everything took place within a single JSF page. In the next chapter, we'll look at page flow within Seam applications, and show how we can easily build up complex routing mechanisms to navigate between pages.