|

|

He who knows others is learned; he who knows himself is wise.

~ Lao Tsu

As the name implies, the facilitator is the leader of the session when facilitating workshops, meetings, training or teams. He or she has the obligation to possess good leadership attributes and use them effectively. A leadership role in facilitating work groups is different from leadership roles in organizations or in politics. Session leader attributes are broken down into three areas as depicted in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 – Facilitation Leadership Framework: “Bringing who you are, to what you do”

This framework has been developed by me based on my practical experience in facilitation and training for three decades. This chapter provides an introduction and insights into the dimensions of these attributes and why a facilitator must inculcate them to be successful:

- Leadership, Values and Ethics (core of the framework)

- Self-Awareness and Style

- Skills and Competencies.

Author Geoff Bellman in his book The Consultant’s Calling wisely uses the phrase “Bringing who you are to what you do.” Who you are as a person and what you do in terms of your services as a consultant/facilitator defines your “Brand,” or your hallmark.

Leadership

Napoleon Hill was an American author in the area of the new thought movement who was one of the earliest producers of the modern genre of personal success literature. He is widely considered to be one of the great writers on success. His most famous work, Think and Grow Rich (1937), is one of the best-selling books of all time (at the time of Hill’s death in 1970, Think and Grow Rich had sold 20 million copies).

Hill’s works examine the power of personal beliefs, and the role they play in personal success. He was an advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt from 1933 to 1936. “What the mind of man can conceive and believe, it can achieve.” is one of Hill’s hallmark expressions. How achievement actually occurs, and a formula for it that puts success in reach of the average person, were the focal points of Hill’s books. (Source: Wikipedia)

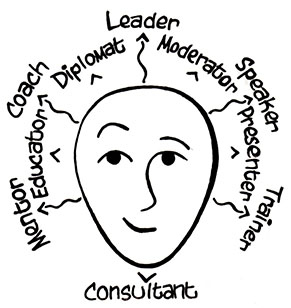

A facilitator plays several roles in the facilitation process, including those of mediator, diplomat, consultant, educator, trainer, coach, speaker, and more. But above all, the facilitator is the leader of the session and is responsible for ensuring that the all participants are fully engaged and participative in all aspects of the session. See Figure 4.2. Leadership does not happen by accident; it is mostly a learned behavior based on personal values and sound principles.

Figure 4.2 – Facilitator’s Many Roles

I have found that the following eleven factors of leadership outlined by Napoleon Hill are critical for a facilitator to conduct workshops and deliver successful results. While these eleven factors are written in the context of leadership in general, I have found these to be equally applicable to the role of a facilitator. I have used current manners of expression as they apply to facilitation, without changing the spirit of his message.

Leadership:

- Unwavering courage based upon knowledge of self, and of one’s occupation. No participant wishes to be dominated by a leader who lacks self-confidence and courage. No intelligent follower will be dominated by such a leader for very long.

- Self-control. The person who cannot control himself or herself can never guide others. Self-control sets a mighty example for work groups, which the more intelligent will emulate.

- A keen sense of justice. Without a sense of fairness and justice, no leader can command and retain the respect of his work groups.

- Definiteness of decision. The person who wavers when making decisions, shows uncertainty in those decisions and cannot lead others successfully.

- Definiteness of plans. Successful leaders plan their work, and work their plan. A leader who moves by guesswork, without practical, definite plans, is comparable to a ship without a rudder. Sooner or later the ship will land on the rocks. In the facilitation process this translates into taking steps to engage and prepare, where every detail is thought through for success.

- The habit of doing more than paid for. One of the challenges of leadership is the necessity for leaders to be willing to do more than they require of their work groups. Facilitators should “go the extra mile” and strive to create customer delight and not just customer satisfaction.

- A pleasing personality. No slovenly, careless person can become a successful leader. Leadership calls for respect. Work groups will not respect leaders who do not grade high on all of the factors of a pleasing personality.

- Sympathy and understanding. Successful leaders must be in sympathy with their session participants. Moreover, they must understand them and their problems and challenges.

- Mastery of detail. Successful leadership calls for mastery of the details of the leader’s position. Facilitators must pay a close attention to all aspects of the facilitation process, including agenda design, conducting the session, and delivering the agreed outputs. This also includes paying a close attention to the energy of the group and making adjustments promptly.

- Willingness to assume full responsibility. Successful leaders must be willing to assume responsibility for any shortcomings in workshop design and usage of tools—should they not be effective. Leaders who try to shift this responsibility will find it difficult to be accepted as leaders by the groups they lead. Leaders should explain why some aspect of the session is not working and make changes immediately to try another tool or technique that is acceptable to the group and offers greater chances of success.

- Cooperation. Successful leaders understand and apply the principle of cooperative effort and induce their session participants to do the same. In facilitation, the participants and their management put their trust in the facilitator to inculcate cooperation and collaboration to achieve the desired objectives.

These eleven factors are governed by the other two dimensions of session leaders shown Figure 4.1: values and ethics.

Values and Ethics

This is the Statement of Values and Code of Ethics of the International Association of Facilitators (IAF). The development of this Code has involved extensive dialogue and a wide diversity of views from IAF members from around the world. A consensus has been achieved across regional and cultural boundaries.

The Statement of Values and Code of Ethics (the Code) was adopted by the IAF Association Coordinating Team (ACT) in June 2004. The Ethics and Values Think Tank (EVTT) continue to provide a forum for discussion of pertinent issues and potential revisions of this Code.

Preamble (In the words of IAF)

Facilitators are called upon to fill an impartial role in helping groups become more effective. We act as process guides to create a balance between participation and results.

We, the members of the International Association of Facilitators (IAF), believe that our profession gives us a unique opportunity to make a positive contribution to individuals, organizations, and society. Our effectiveness is based on our personal integrity and the trust developed between ourselves and those with whom we work. Therefore, we recognize the importance of defining and making known the values and ethical principles that guide our actions.

This Statement of Values and Code of Ethics recognizes the complexity of our roles, including the full spectrum of personal, professional and cultural diversity in the IAF membership and in the field of facilitation. Members of the International Association of Facilitators are committed to using these values and ethics to guide their professional practice. These principles are expressed in broad statements to guide ethical practice; they provide a framework and are not intended to dictate conduct for particular situations. Questions or advice about the application of these values and ethics may be addressed to the International Association of Facilitators.

Statement of Values

As group facilitators, we believe in the inherent value of the individual and the collective wisdom of the group. We strive to help the group make the best use of the contributions of each of its members. We set aside our personal opinions and support the group’s right to make its own choices. We believe that collaborative and cooperative interaction builds consensus and produces meaningful outcomes. We value professional collaboration to improve our profession.

Code of Ethics

- Client Service: We are in service to our clients, using our group facilitation competencies to add value to their work. Our clients include the groups we facilitate and those who contract with us on their behalf. We work closely with our clients to understand their expectations so that we provide the appropriate service, and that the group produces the desired outcomes. It is our responsibility to ensure that we are competent to handle the intervention. If the group decides it needs to go in a direction other than that originally intended by either the group or its representatives, our role is to help the group move forward, reconciling the original intent with the emergent direction.

- Conflict of Interest: We openly acknowledge any potential conflict of interest. Prior to agreeing to work with our clients, we discuss openly and honestly any possible conflict of interest, personal bias, prior knowledge of the organization or any other matter which may be perceived as preventing us from working effectively with the interests of all group members. We do this so that, together, we may make an informed decision about proceeding and to prevent misunderstanding that could detract from the success or credibility of the clients or ourselves. We refrain from using our position to secure unfair or inappropriate privilege, gain, or benefit.

- Group Autonomy: We respect the culture, rights, and autonomy of the group. We seek the group’s conscious agreement to the process and their commitment to participate. We do not impose anything that risks the welfare and dignity of the participants, the freedom of choice of the group, or the credibility of its work.

- Processes, Methods, and Tools: We use processes, methods, and tools responsibly. In dialogue with the group or its representatives we design processes that will achieve the group’s goals, and select and adapt the most appropriate methods and tools. We avoid using processes, methods or tools with which we are insufficiently skilled, or which are poorly matched to the needs of the group.

- Respect, Safety, Equity, and Trust: We strive to engender an environment of respect and safety where all participants trust that they can speak freely and where individual boundaries are honored. We use our skills, knowledge, tools, and wisdom to elicit and honor the perspectives of all. We seek to have all relevant stakeholders represented and involved. We promote equitable relationships among the participants and facilitator and ensure that all participants have an opportunity to examine and share their thoughts and feelings. We use a variety of methods to enable the group to access the natural gifts, talents and life experiences of each member. We work in ways that honor the wholeness and self-expression of others, designing sessions that respect different styles of interaction. We understand that any action we take is an intervention that may affect the process.

- Stewardship of Process: We practice stewardship of process and impartiality toward content. While participants bring knowledge and expertise concerning the substance of their situation, we bring knowledge and expertise concerning the group interaction process. We are vigilant to minimize our influence on group outcomes. When we have content knowledge not otherwise available to the group, and that the group must have to be effective, we offer it after explaining our change in role.

- Confidentiality: We maintain confidentiality of information. We observe confidentiality of all client information. Therefore, we do not share information about a client within or outside of the client’s organization, nor do we report on group content, or the individual opinions or behavior of members of the group without consent.

- Professional Development: We are responsible for continuous improvement of our facilitation skills and knowledge. We continuously learn and grow. We seek opportunities to improve our knowledge and facilitation skills to better assist groups in their work. We remain current in the field of facilitation through our practical group experiences and ongoing personal development. We offer our skills within a spirit of collaboration to develop our professional work practices.

Self-Awareness and Style

Being aware of one’s strengths and shortcomings in the role of a session leader helps better manage the facilitation process and creates opportunities to continuously improve upon them with every engagement. One’s personal beliefs, values and qualities result in the “style” of a facilitators conduct. Style is the mode of expressions of the self. The style influences the participants and stakeholders in a way that nurtures trust and generates confidence in the leadership of the facilitator. Of course in training workshops, the style permeates in the subject matter of knowledge transfer. Here are some considerations that facilitators must be aware of and have strategies regarding style of conduct and expression:

Dress: Dress for success is an old axiom. Success for a facilitator means being presentable and professional appropriate to that role. The growing scientific field called embodied cognition suggests that we think not just with our brains but with our bodies, reports Sandra Blakeslee in the New York Times (April 3, 2012). If you wear a white coat that you believe belongs to a doctor, your ability to pay attention increases sharply. In the article, Dr. Adam D. Galinsky, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, is quoted as saying, “Our thought processes are based on physical experiences that set off associated abstract concepts. Now it appears that those experiences include the clothes we wear.” If our behavior is influenced by what we wear, a facilitator must consider a scientific approach to dress.

Two views are commonly prevalent regarding a facilitator’s dress code. Some believe that a facilitator should dress just as the audience would. For example if the audience, or participants, dress in casual clothing because their organization rules allow that dress code then the facilitator should dress casual as well. Others believe that the facilitator, being a session leader must dress one notch above the audience.

Unless a manager of a given organization is leading the session, I believe the second point of view is the correct one—that the facilitator should dress one notch above. For example, if the audience is dressed in business casual then the facilitator should wear a business suit or jacket and tie for men and a jacket for women. This style of dress sends a message to the participants that you are in charge and are ready for your role as their session leader. After the initial introductions and kick off, it’s okay to take the jacket off and put it away for conducting the rest of the business. Of course the dress code mentioned here is for Western cultures; for different geographies and cultures, facilitators may use their own preferred dress practices.

Eye Contact and Glasses: Direct eye contact is a powerful communicator. It is imperative that facilitators who wear eyeglasses have non-glare glasses that don’t reflect light. Regular glasses reflect light and the audience cannot see the eyes of the facilitator through the glasses and, therefore, cannot establish the connection that is so important for human interaction.

Connection with Audience: As stated before, direct eye contact is a powerful and effective communicator. In public speaking, where there may be ten people or a hundred people or more, speakers should scan the entire audience to make a personal connection when making key points. This gives individuals in the audience the perception that they’re getting personal attention. Scanning from left to right or right to left across the audience may be referred to as the “Light House Beacon.” As the Light House Beacon, facilitators should sweep the audience with their eyes, resting only one to three seconds or less on each person (unless one is in a dialogue mode). This ensures attention and engagement.

Active Listening: It is said that the reason human beings have two ears and one mouth is so that they can listen more and speak less. This skill is critical for facilitators because they must simultaneously play many roles while managing the current situation and thinking of next steps to come. A basic technique called The Listening Ladder helps facilitators in this important aspect: Look at the person speaking to you. Ask questions. Don’t interrupt or be interrupted. Don’t change the subject. Empathize. Respond verbally and nonverbally.

“Color” in Your Voice: Voice timbre is a powerful medium of communication when speaking, presenting, or managing any other activity of a given session. Speak loud enough to throw your voice to the back of the room so that the words are clear to one and all. Vary your tone and pitch and repeat key phrases and learning points with a different vocal emphasis. This may be referred to as putting “color in your voice.” This concept is particularly impactful when telling stories, using quotations, and expressing relevant metaphors. Use the Power of Pause. Pause at the various key intervals and emphasize sparkle and freshness in your voice. The audience draws energy from the facilitator’s voice.

Body Language and Enthusiasm: Appropriate use of gestures expresses emotion through the body to make a point or convey a particular feeling. Using hands, pointing with the fingers, raising eye brows, looking around, shaking your head, and other gestures convey messages through a “visual language” which, when combined with color in your voice and pausing with purpose, enhances the impact of what is being communicated to the audience. I use a gesture of clapping my hands loudly when I want to show my passion for making a point. It grabs the attention of the participants and promotes an environment of enthusiasm.

Mannerisms: Check your dress, hair, and clothing before standing up and presenting. Avoid close or tense body postures. Be aware of your verbal tics and practice eliminating the non-words such as “uh,” “you know,” and others. Great speakers don’t use non-words. It is important to greet the participants as they arrive. This concept may be referred to as connection before content.

Be aware of the cultural norms of the local geography. Respect diversity of geographies, people and cultures. For example, some Eastern cultures have a very respectful way of handing out their business cards. They hold it with both hands, card text facing the recipient and present it with a slight bow. The recipients reciprocate with the similar gesture.

Avoid referencing politics, religion, ethnicity, war, or any other topic of contention or sensitivity (unless the session topic is one of these issues). I use metaphors and narrate lessons of war relevant to my topics only after asking permission from the audience.

Discussion and Debate: This is an integral part of group sessions. To solve problems, develop solutions, and improve products and services, healthy discussion is critical. Several techniques and tools are designed by the facilitator in the Prepare Process step. Here are some key considerations for facilitating discussion:

- Questioning: Avoid closed questions such as, “Who can tell me on which date…?” Instead use open question such as, “What might be the timeframe for…?”

- Lubricators: Use verbal and nonverbal lubricators that demonstrate your attention to the one speaking. Also, most participants’ questions may not be questions! Clarify and promote dialogue by using the reflective or deflective approach. For example:

- Verbal: “I see.” or “That is interesting.”

- Nonverbal: Nodding, leaning forward, and constant eye contact.

- Reflective: “If I understand correctly, you are asking…”

- Deflective: Address the group, saying, “How does the rest of the group feel about…?” or to the individual, “You have obviously done some thinking on this. What’s your view on…?”

Gratitude: A facilitator’s session has many enablers who contribute to the success of every phase of the process. The session coordinator, the wait staff who served breakfast and lunch, the hotel staff who helped with the audio system, and others deserve expressions of thanks because they “facilitated” their end of the service. Usually, when a session concludes, the participants close their laptops and pack their briefcases and off they go. The support staff is almost invisible to them. I make it a practice to call all the support staff before the wrap-up and publically acknowledge their contribution so that the participants may give a round of applause as a visible gesture of their appreciation. It is not just good manners, but it’s good for the soul of everyone whose energy flowed in that session—one and all. Robert Louis Stevenson said, “The man who forgets to be grateful has fallen asleep in life.”

Learning on the Fly: In FYI, For Your Improvement, A Development and Coaching Guide, Michael M. Lombardo and Robert W. Eichinger have identified Learning on the Fly as a crucial competency and describe it thus:

Most of us are good at applying what we have seen and done in the past. Most of us can apply solutions that have worked for us before. We are all pretty good at solving problems we’ve seen before. A rarer skill is doing things for the first time. Solving problems we’ve never seen before. Trying solutions we have never tried before. Analyzing problems in new contexts and in new ways. With the increasing pace of change, being quick to learn and apply first time solutions is becoming a crucial skill. It involves taking risks, being less than perfect, discarding the past, going against the grain, and cutting new paths. The one who is skilled in this competency:

- Learns quickly when facing new problems

- Is a relentless and versatile learner

- Is open to change

- Analyzes both successes and failures for clues to improvement

- Experiments and will try anything to find solutions

- Enjoys the challenge of unfamiliar tasks

- Quickly grasps the essence and the underlying structure of anything.

Being a leader of the facilitation process and the session, you have the obligation to develop and possess the Learning on the Fly attributes outlined above. I also refer to this capability as the Learning Agility of a Facilitator, the ability to rapidly respond to change by understanding the current situation quickly and determining possibilities for action through new information. To inculcate these attributes, the facilitator must be an avid reader of a variety of subjects, have a library of resources such as methods, techniques and tools to draw from on a short notice, and have the ability to research and network with other professionals as and when needed.

Genius ... is the capacity to see ten things where the ordinary man sees one.

~ Ezra Pound, American expatriate poet and critic

Influencing Others: As a facilitator you wear multiple hats: educator, trainer, consultant, and even coach and mentor. Participants will look up to you and observe your behavior, your actions, and how you lead them in a session. This leaves an impact on the participants that they may take away as a learning experience and a technique to apply somewhere else in their own work engagements. In essence, you are leaving your legacy at every step. This means you have a tremendous responsibility to say and do the right things.

Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People outlines some attributes that should be considered in the role of a facilitator.

- Be sincere. Do not promise anything that you cannot deliver.

- Be empathetic. Ask yourself what it is the other person really wants (e.g., objectives identified by the workshop manager and participants).

- Consider the benefit the person (group/participants) will receive from doing what you suggest.

- Match those benefits to other person’s (group’s/participant’s) wants.

- When you make your request, put it in a form that will convey to the other person (group/participants) the idea that s/he personally will benefit.

When I was writing this section of the chapter, the sixteen-year-old Pakistani advocate of education for girls in oppressive environments, Malala Yousafzai, was making a powerful speech at the United Nations. In closing her emotional and enthusiastic speech advocating the rights of children, she raised her index finger and said, “One child, one teacher, one book, and one pen can change the world.” With passion in her voice, she said this while moving her body along with the pointed index figure as she scanned the audience from one end of the hall to the other.

This is an excellent example of the points made in this section: Malala opened her speech with humbleness, showing good manners, and she made eye contact with the entire audience and connected with them. She used color in her voice and through body language demonstrated enthusiasm. She very gracefully showed gratitude to all those who helped her recover from the shot fired point blank at her head by terrorists for speaking up for girls’ education in Pakistan. Watching her speak, I was impressed by the number of attributes discussed in this chapter that this young woman displayed.

Self-Assessment

In the Self-Awareness and Style piece of the Facilitation Leadership Framework outlined in Figure 4.1, take a few moments and with a pencil identify in “Your Notes” the items you believe you may wish to explore for learning and improvement. This can become input to your development plan described in Chapter 11.

|

Your Notes: |

Skills and Competencies

Foundational Skill Set

The following seven foundational skills are essential for anyone in the role of a facilitator. To develop these skills, facilitators need to be aware of their personal strengths and weaknesses and then diligently work on acquiring and practicing those competencies for their professional selves. Facilitators must be at their best while facilitating sessions. This is the measure of their competency:

- Active Listening

- Questioning

- Information Gathering and Analysis

- Public Speaking

- Presentation Skills

- Intervening (Summarizing and Paraphrasing)

- Managing Group Dynamics.

Comprehensive Skill Set

For facilitators to continue a professional journey of this art and craft, the International Association of Facilitators (IAF) has developed Core Facilitator’s Competencies. In addition, they have a professional certification in place which is outlined below and is also referenced in Chapter 12.

Background

The International Association of Facilitators (IAF™) is the worldwide professional body established to promote, support and advance the art and practice of professional facilitation through methods exchange, professional growth, practical research and collegial networking. In response to the needs of members and their customers, IAF established the Professional Facilitator Certification Program. The Professional Facilitator Certification Program provides successful candidates with the professional credential “IAF CertifiedTM Professional Facilitator—CPF.” This credential is the leading indicator that the facilitator is competent in each of the basic facilitator competencies. The Core Facilitator Competencies© IAF™ 2003 document provides an overview of the competency framework that is the basis of the CPF certification.

The competency framework described in the Core Facilitator Competencies was developed over several years by IAF with the support of IAF members and facilitators from all over the world. The competencies reflected in the document and assessed in the Certification Process, form the basic set of skills, knowledge, and behaviors that facilitators must have in order to be successful facilitating in a wide variety of environments. Copies of this document are available free of charge from the IAF web site (http://www.iaf-world.org) or from the certification program administrator, at [email protected]. (Reference: Foundational Facilitator Competencies© IAF™, 2003, Version 1.0)

The Competencies

A. Create Collaborative Client Relationships

- Develop working partnerships

- Clarify mutual commitment

- Develop consensus on tasks, deliverables, roles and responsibilities

- Demonstrate collaborative values and processes such as in co-facilitation.

- Design and customize applications to meet client needs

- Analyze organizational environment

- Diagnose client need

- Create appropriate designs to achieve intended outcomes

- Predefine a quality product and outcomes with client.

- Manage multi-session events effectively

- Contract with client for scope and deliverables

- Develop event plan

- Deliver event successfully

- Assess / evaluate client satisfaction at all stages of the event / project.

B. Plan Appropriate Group Processes

- Select clear methods and processes that

- Foster open participation with respect for client culture, norms and participant diversity

- Engage the participation of those with varied learning / thinking styles

- Achieve a high quality product / outcome that meets the client needs.

- Prepare time and space to support group process

- Arrange physical space to support the purpose of the meeting

- Plan effective use of time

- Provide effective atmosphere and drama for sessions.

C. Create and Sustain a Participatory Environment

- Demonstrate effective participatory and interpersonal communication skills

- Apply a variety of participatory processes

- Demonstrate effective verbal communication skills

- Develop rapport with participants

- Practice active listening

- Demonstrate ability to observe and provide feedback to participants.

- Honor and recognize diversity, ensuring inclusiveness

- Create opportunities for participants to benefit from the diversity of the group

- Cultivate cultural awareness and sensitivity.

- Manage group conflict

- Help individuals identify and review underlying assumptions

- Recognize conflict and its role within group learning / maturity

- Provide a safe environment for conflict to surface

- Manage disruptive group behavior

- Support the group through resolution of conflict.

- Evoke group creativity

- Draw out participants of all learning/thinking styles

- Encourage creative thinking

- Accept all ideas

- Use approaches that best fit needs and abilities of the group

- Stimulate and tap group energy.

D. Guide Group to Appropriate and Useful Outcomes

- Guide the group with clear methods and processes

- Establish clear context for the session

- Actively listen, question and summarize to elicit the sense of the group

- Recognize tangents and redirect to the task

- Manage small and large group process.

- Facilitate group self-awareness about its task

- Vary the pace of activities according to needs of group

- Identify information the group needs, and draw out data and insight from the group

- Help the group synthesize patterns, trends, root causes, frameworks for action

- Assist the group in reflection on its experience.

- Guide the group to consensus and desired outcomes

- Use a variety of approaches to achieve group consensus

- Use a variety of approaches to meet group objectives

- Adapt processes to changing situations and needs of the group

- Assess and communicate group progress

- Foster task completion.

E. Build and Maintain Professional Knowledge

- Maintain a base of knowledge

- Knowledgeable in management, organizational systems and development, group development, psychology, and conflict resolution

- Understand dynamics of change

- Understand learning/ thinking theory.

- Know a range of facilitation methods

- Understand problem solving and decision-making models

- Understand a variety of group methods and techniques

- Know consequences of misuse of group methods

- Distinguish process from task and content

- Learn new processes, methods, and models in support of client’s changing/emerging needs.

- Maintain professional standing

- Engage in ongoing study / learning related to our field

- Continuously gain awareness of new information in our profession

- Practice reflection and learning

- Build personal industry knowledge and networks

- Maintain certification.

F. Model Positive Professional Attitude

- Practice self-assessment and self-awareness

- Reflect on behavior and results

- Maintain congruence between actions and personal and professional values

- Modify personal behavior / style to reflect the needs of the group

- Cultivate understanding of one’s own values and their potential impact on work with clients.

- Act with integrity

- Demonstrate a belief in the group and its possibilities

- Approach situations with authenticity and a positive attitude

- Describe situations as the facilitator sees them and inquire into different views

- Model professional boundaries and ethics (as described in the ethics and values statement).

- Trust group potential and model neutrality

- Honor the wisdom of the group

- Encourage trust in the capacity and experience of others

- Vigilant to minimize influence on group outcomes

- Maintain an objective, non-defensive, non-judgmental stance.

Self-Assessment

Check off each item in the competencies checklist with a “+” sign if you are good at the skill and a “-” sign if you need development. This can be integrated into your development plan, described in Chapter 12.

Helpful Hints

Leadership, Values, and Ethics permeate every aspect of Self-Awareness & Style and Skills & Competencies. Therefore, to achieve professional excellence, it is incumbent upon facilitators, in all their roles, to adopt, strive for, and practice these dimensions in every engagement. Over a period of time, these attributes become habits and become embedded in the psyche of good facilitators. Bringing who you are to what you do is a “Brand” for which you are respected and recognized. Facilitation leadership is a rewarding and satisfying journey.