Leading High-Performance NextGen Teams

Demystifying Teams

To understand how teams deliver extra performance, it is important to distinguish between teams and other forms of working groups. That distinction turns on performance results. A working group’s performance is a function of what its members do as individuals. A team’s performance includes both individual results and what is called “collective work products.” A collective work product is what two or more members must work on together, such as interviews, surveys, or experiments. Whatever it is, a collective work product reflects the joint, real contribution of team members.

Working groups are both prevalent and effective in large organizations where individual’s accountability is most important. The best working groups come together to share information, perspectives, and insights; to make decisions that help each person do their job better; and to reinforce individual performance standards. But the focus is always on individual goals and accountabilities. Working-group members don’t take responsibility for results other than their own. Nor do they try to develop incremental performance contributions requiring the combined work of two or more members (Katzenbach and Smith 1993).

Teams differ fundamentally from working groups because they require both individual and mutual accountability. Teams rely on more than group discussion, debate, and decision making; they rely more on sharing information and best-practice performance standards. Teams produce discrete work products through the joint contributions of their members. This is what makes possible performance levels greater than the sum of all the individual team members. Simply stated, a team is more than the sum of its parts.

Katzenbach and Smith (1993) stated that “a team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable” (p. 45). Let’s examine further this definition.

A small number of people: The optimal number of people in a team is generally between five and nine. While more team members bring a greater diversity of perspectives and ideas, the difficulty of consensus decision making increases dramatically. Subgroups can be created, but then the entire team is at risk of losing sight of the big picture.

Complementary skills: In establishing a team, it is critical to ensure that there is a mix of diverse, yet complementary, skills such as technical, functional, and interpersonal abilities.

Committed to a common purpose: Without a unified purpose, the team has no yardstick against which to measure its performance.

Common performance goals: Teams share performance goals or objectives; if a goal or objective is not achieved, the entire team is accountable. Commitment to these common performance objectives results in higher productivity and raises motivation levels.

Common approach: Objectives represent the “task” element of performing successfully; a common approach represents the “group process” element of working together. Neither is more important than the other, but without agreeing on how the team will interact, the chances of completing the task are pretty low!

Mutually accountable: This refers to the shared ownership and responsibility that is fundamental to real teamwork. If something goes wrong, there should not be any finger-pointing but rather a group effort to fix the current situation and prevent future problems. Everyone should feel free to ask for help, just as they should feel free to offer assistance. In a team, individual and team success are one and the same.

Importance of Teams in VUCA-Driven Business Environment

Teams have become the principal building block of the strategy of successful organizations. With teams at the core of corporate strategy, the success of an organization will often depend on how well each team member operates and collaborates with others.

Today’s highly disruptive, as well as volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA)–driven networked business environment not only provides a challenging environment for leaders to operate but also requires them to depend on their teams, which is critically important to getting work done (Bawany 2016b). Yet, not all teams are created equal. Some fail to perform or perform below expectations. Some start out well but later lose their focus and energy. Teams are extremely valuable if they are working well. They are very costly if they are not. It is critical for leaders to find ways to ensure their teams are working effectively and are achieving their results.

In most teams, the energies of individual members work at cross-purposes. Individuals may work extraordinarily hard, but if their efforts do not translate into a team effort, it would result in wasted energy. By contrast, when a team becomes more aligned, a commonality of direction emerges, and individual energies harmonize. You have a shared vision and an understanding of how to complement each other’s efforts. As jazz musicians say, “You are in the groove” (Bawany, 2014b).

A team can have everything going for it—the brightest and most qualified people, access to resources, and a clear mission—but can still fail because it lacks group emotional intelligence.

Moreover, managers need to develop the self-awareness and interpersonal skills associated with a high level of emotional intelligence, as do teams. One way for leaders to help their teams build this capability is to understand and ensure that their teams move successfully through the stages of small-group development: membership, control, and cohesion. These stages are experienced by all teams. If teams are not well led and facilitated through them, their chances of achieving results are substantially reduced (Bawany 2014a).

Characteristics of Effective Teams

An organization and its leaders put a great deal of effort into assembling high-performing teams. This means that the power of a team must lie in its capacity to perform at levels and deliver results greater than the sum of its parts. Considerable resources are often expended to ensure teams reach their potential. For team members, as well as other people in an organization, recognizing when a team is doing well is important. When improvement is needed, it is important to make positive changes. However, sometimes it is helpful to take a step back in order to recognize when a team is working effectively. The workings of a highly effective team are not always obvious or intuitive to everyone. Teams that are highly effective are likely to have the five characteristics described in the following.

Well-Defined Team Charter and Operating Philosophy

The single most important ingredient in team success is a clear, common, and compelling task. The power of a team flows out of a purpose to which every team member is aligned. The task of any team is to accomplish an objective by performing at exceptional levels. Teams are not ends in themselves; rather they are a means to an end. Therefore, high-performance teams should be mission-directed and be judged by their results ultimately. This would include the team mission, purpose, values, and goals. Effective teamwork includes having a synergistic social entity that works toward a common goal or goals. Often, high-performance teams exemplify total commitment to the work and to each other.

Katzenbach and Smith (1993) stated, “Common sense suggests that teams cannot succeed without a shared purpose” (p. 2). While this may be an obvious statement, teams often form (or are developed) without a clear direction or meaning even though many researchers have explained that employees are inclined to do better when they know how to do their jobs and also why they are doing them. Teams that seek higher levels of performance should ensure that each member understands and supports the true meaning and value of their team’s mission and vision. Clarifying the purpose in this manner and linking each individual’s role and responsibilities is a major contributor for tapping into team potential.

Clarity of Roles and Performance Standards of Team Members

High-performance teams are also characterized by crystal-clear roles. Every team member is clear about their particular role as well as the roles of the other team members. Roles are all about how we design, divide, and deploy work among the team. While the concept is compellingly logical, many teams find it very challenging to implement it in practice. There is often a tendency to take role definition to extremes or not take it far enough. But when they get it right, team members discover that making their combination more effective and leveraging their collective efforts is key to achieving synergistic results.

Clear performance standards are essential to high-performing teams. Such standards provide a system of accountability that also feeds into the performance ethic (Katzenbach and Smith 1993). This is an ethic that supports results for customers, employees, and shareholders, recognizing that each is of critical importance and must be balanced with great care and consideration.

Driving standards are certain pressures. These pressures include the individual’s performance expectations, team pressure to perform, team leader pressure, the consequences of success or failure, and other external pressures (e.g., the larger the organization, the larger the crowd) that compel one to excel. According to Larson and LaFasto (1989), “people with high standards are those people who do ordinary things in an extraordinary way” (p. 100). When helping people reach the extraordinary, it is important to remember that setting standards must be a flexible process. Larson and LaFasto also provided three common features of developing standards of excellence: (i) setting standards that include a variety of variables; (ii) variables that include individual commitment, motivation, self-esteem, and performance; and (ii) mutual accountability and dedication to reviewing and reworking standards to keep them fresh and valuable for the team.

Shared Norms and Culture

Like rules that govern group behavior, norms can be helpful in assisting team development and performance. For example, Jehn and Mannix (2001) proposed that high-performance teams build “open discussion” norms to promote task conflict—a type of conflict associated with high-performance teams. Other norms of high-performance teams include high levels of respect among members and a cohesive and supportive team environment. Any number of norms may exist for a given team, but high-performing teams use norms mostly to help govern behavior. In addition to having team norms, teams also benefit from organizing their team standards. As asserted by Larson and LaFasto (1989), “openly articulated or haphazardly applied, standards define those relevant and very intricate expectations that eventually determine the level of performance a team deems acceptable” (p. 95). Standards change the nature of performance by setting the bar at a new level—a level that is clearly defined.

Teams should be recognized and integrated within their organizations (Pearce and Ravlin 1987). Organizations need to clearly define their expectations and mechanisms of accountability for all teams (Sundstrom, De Meuse, and Futrell 1990). Organizational culture needs to transform shared values into behavioral norms (Blechert, Christiansen, and Kari 1987). For example, team success is fostered by a culture that incorporates shared experiences of success. In times of economic rationalizations, cultural conflicts and inconsistency may arise between the norms of maintaining the standards and adhering to the organization’s mission. Team members with higher status also have less regard for team norms and may exacerbate internal conflict.

Excellent Communication and Collaboration

Communication is the very means of cooperation or collaboration between team members. One of the primary motives for companies to implement teams is that team-based organizations are more responsive and move faster. A team, or the organization in which it resides, cannot move faster than it communicates. Fast, clear, accurate communication is a hallmark of high levels of team performance. Such teams have mastered the art of straight talk; there is little wasted motion from misunderstanding and confusion. Ideas move like quicksilver. The team understands that effective communication is key to thinking collectively and finding synergy in team solutions. As a result, team members approach communication with determined intentionality. They talk about it a lot and put a lot of effort into keeping it good and getting better.

While high-performing teams experience certain types of healthy conflict and yet are regarded as good communicators, research studies indicate that different types of communication, even different levels of perceptions of the amount of conflict, can have different types of effects. Different communication strategies appear to yield different results (including satisfaction) among those who participated, suggesting that the best forms of communication are dependent on the workgroup and their goals and objectives. Open communication in high-performing teams means a focus on coaching instead of directing (Regan 1999). The value of coaching has emerged over the past several years as a process for helping individuals think for themselves. Coaching is seen as a facilitative process where team leaders or members help facilitate the process of self- and group discovery. By utilizing coaching more frequently, individuals become less dependent and more able to take greater levels of responsibility.

Effective Leadership

The more complex and dynamic the team’s task, the more a leader is needed. Leadership should reflect the team’s stage of development. Leaders need to maintain a strategic focus to support the organization’s vision, facilitate goal setting, educate their team, and evaluate their teams’ achievements (Proctor-Childs, Freeman, and Miller 1998). When leaders delegate responsibility appropriately, team members become more confident and autonomous and perform better.

One of the leader’s roles is to ensure that the team has the right number of members with the appropriate mix and diversity of task and interpersonal and complementary skills. A balance between homogeneity and heterogeneity of members’ skills, interests, and background is preferred (Hackman 1990). Homogeneous teams are composed of similar individuals who complete tasks efficiently with minimal conflict. By contrast, heterogeneous teams incorporate membership diversity and therefore facilitate innovation and problem-solving (Pearce and Ravlin 1987).

High-performing leaders usually accompany high-performance teams. High-performing teams have leaders who, when times are certain and peaceful, are able to take a proactive stance and help the team stay ahead. In fact, Regan (1999) encouraged team leaders to create a sense of distress and urgency so as not to be surprised when confronted by external crises.

Regan purported those essential leadership qualities include the following:

- Having a vision, meaning one should see the crisis before it happens and act upon it

- Convincing the opinion leaders of the importance of the goals at hand

- Organizing quantitative goals

- Being persistent in asking for the goals to be met

- Endurance testing—leaders must remain steadfast even when their team members try to test their commitment

- The ability to induce creativity once goals are set

- Staying out of the team’s way

Katzenbach and Smith (1993) cited six elements necessary for good team leadership:

- Team leaders must keep the team’s purpose, goals, and approach relevant and meaningful.

- Team leaders should continue to build commitment and confidence.

- Team leaders must ensure that their members are always enhancing their skills—including technical, problem-solving, decision-making, and interpersonal or teamwork skills.

- Effective team leaders are skillful at managing relationships from the outside, with a focus on removing obstacles that get in the way of team performance.

- Team leaders provide opportunities for others and are the last to seek credit.

- Team leaders don’t shy away from getting in the trenches and doing the real work.

While the authors contend that most individuals can develop effective skills to be a team leader, they suggest these components are vital for success.

Why Do Teams Fail?

In The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable, Patrick Lencioni tells the story of Kathryn Petersen, DecisionTech’s CEO, who faced the ultimate leadership crisis: How to unite a team that is in such disarray that it threatens to bring down the entire company. Will she succeed? Will she be fired? Lencioni’s tale serves as a timeless reminder that leadership requires courage and insight (Lencioni 2002).

As difficult as it is to build a cohesive team, it is not complicated. In fact, keeping it simple is critical, whether you run the executive staff of a multinational company or head a small department in a larger organization or you are merely a member of a team that needs improvement. Lencioni reveals the five dysfunctions that are at the very heart of why teams—even the best ones—often struggle. He outlines a powerful model (see Figure 6.1) and actionable steps that can be used to overcome these common hurdles and build a cohesive, effective team (Lencioni 2002).

Figure 6.1 Lencioni’s framework of five dysfunctions of teams

According to Lencioni, most teams unknowingly fall victim to five interrelated dysfunctions. Teams that suffer from even one of the five are susceptible to the other four. Solving all the five is required to create a high-functioning team. The five dysfunctions are displayed in a pyramid.

Dysfunction 1: Absence of trust: When team members do not trust one another, they are unwilling to be vulnerable within the team. It is impossible for a team to build a foundation for trust when team members are not genuinely open about their mistakes and weaknesses.

Dysfunction 2: Fear of conflict: Failure to build trust sets the stage for the second dysfunction. Teams without trust are unable to engage in passionate debate about ideas. Instead, they are guarded in their comments and resort to discussions that mask their true feelings.

Dysfunction 3: Lack of commitment: Teams that do not engage in healthy conflict will suffer from the third dysfunction. Because they do not openly express their true opinions or engage in open debate, team members will rarely commit to team decisions, though they may feign agreement in order to avoid controversy or conflict.

Dysfunction 4: Avoidance of accountability: A lack of commitment creates an atmosphere where team members do not hold one another accountable. Because there is no commitment to a clear action plan, team members hesitate to hold one another accountable for actions and behaviors that are contrary to the good of the team.

Dysfunction 5: Inattention to results: The lack of accountability makes it possible for people to put their own needs above the team’s goals. Team members will focus on their own career goals or recognition for their departments to the detriment of the team.

A weakness in any one area can cause teamwork to deteriorate. The model is easy to understand and yet can be difficult to practice because it requires high levels of discipline and persistence.

Resolving the Challenges in Leading High-Performing Teams

Building Trust

Lencioni states that trust lies at the heart of a functioning, cohesive team and that without trust teamwork is all but impossible. As a leader, you must encourage your team members to admit their weaknesses, take risks by offering one another feedback and assistance, focus their energy on important issues, and be more willing to ask for help.

Teamwork begins by building trust. And the only way to do that is to overcome our need for invulnerability (putting up a front). Trust is the confidence among team members that their peers’ intentions are good and that there is no reason to be protective or careful around the group. In essence, teammates must get comfortable being vulnerable to each other.

Removing the Fear of Conflict

Teams that avoid conflict often do so in order to avoid hurting team members’ feelings and then end up encouraging dangerous tension as a result. When team members do not openly debate and disagree with important ideas, they often turn to back-channel personal attacks, which are far nastier and more harmful than any heated argument over issues. The leader must call out sensitive issues and force the team members to work through them.

When the leader sees that people engaged in healthy conflict are uncomfortable, they should remind them that what they are doing is necessary—this can keep them encouraged. At the end of the discussion, remind the participants that the healthy conflict they just engaged in is good for the team. The leader should restate the agreements and goals arrived at and restate everyone’s commitments and actions expected.

Achieving Commitment

According to Lencioni, commitment is a function of clarity and buy-in. Leaders need to ensure that their teams make timely and clear decisions with buy-in from all team members, even those who do not agree with the decision. Teams with commitment have common objectives, move forward without hesitation, change direction when necessary, and learn from their mistakes.

To reach commitment, the five dysfunctions model recommends techniques such as establishing clear deadlines and communicating the team’s goals throughout the organization. This happens through effective discussion, which is a reflection of feedback. Feedback involves active listening and understanding other team members’ concerns and viewpoints. It also includes adapting communication to match the styles of other team members.

Ensuring Accountability

Accountability requires team members to call their peers on performance or behaviors that might hurt the team. Teams where members hold one another accountable identify problems quickly by questioning one another’s actions, hold one another to the same standards, and avoid needless bureaucracy around managing performance. Members of great teams improve their relationships by holding one another accountable, thus demonstrating they respect each other and have high expectations for one another’s performance.

One of the best and healthiest motivators for a team is peer pressure. Clarify publicly exactly what the team needs to achieve. The enemy of accountability is ambiguity. Perform simple and regular progress reviews. Shift rewards away from individual performance to team achievement. That will create a culture of accountability because a team is unlikely to stand by quietly and fail because a peer is not pulling their weight. Once a leader has created a culture of accountability in a team, they must then be willing to become the ultimate arbiter of discipline when the team itself fails. An optimistic outlook is critical since it communicates confidence to other team members and to the rest of the organization that the team is on the right track. An optimistic team is more likely to hold one another accountable for achieving the team’s goals.

Driving Results

The ultimate dysfunction occurs when members put their own status or personal goals above the best interests of the team. Teams that focus on results minimize this type of self-centered behavior. The key is to make the collective ego greater than the individual ones. When everyone is focused on results and use them to define success, it is difficult for the ego to get out of hand. If the team loses, everyone loses. Eliminate ambiguity by having clearly agreed on and set goals. (A sports team knows at the end of the game how well it did based on the results.)

Adopt a set of common goals and measurements, then use them to make collective decisions on a daily basis. Publicly declaring the team’s results and offering results-based rewards are techniques for managing this dysfunction. Without personal conscientiousness, perseverance, flexibility, and optimism, it would be difficult, if not impossible, for teams to achieve results. Innovation is another aspect of competence that is particularly important for achieving results. Teams that are creative and generate innovative products and solutions will inevitably achieve results that are superior to those of their competitors.

The SCORE Framework for Developing High-Performance Teams

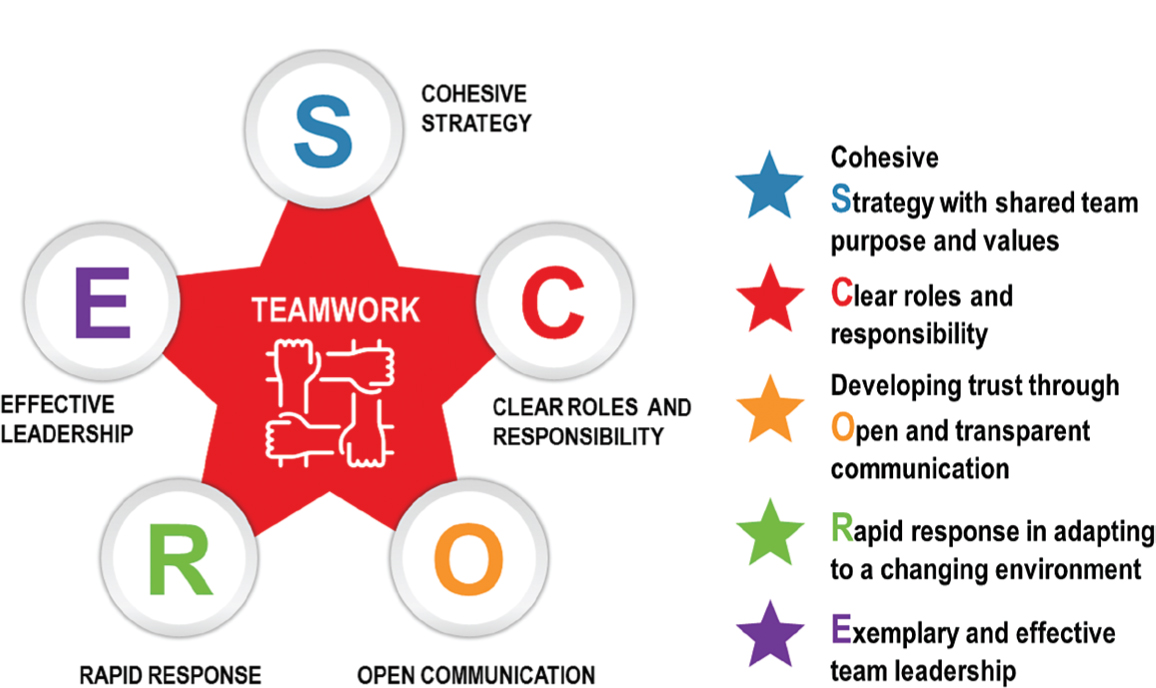

Despite society’s emphasis on individuality, the critical work of business today is undertaken by teams, whether real or virtual. The success of organizations can be closely linked to how well these teams of diverse individuals perform, and it is clear that some teams do truly excel. Based on data gathered from extensive consulting engagements by the Centre for Executive Education (CEE) over a decade, several key elements have been identified as critical in high-performance organizations. These elements constitute the SCORE framework for high-performing teams (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 The SCORE framework for developing high-performing teams

A high-performing team demonstrates a high level of synergism—the simultaneous actions of separate entities that together have a greater effect than the sum of their individual efforts. For example, it is possible for a team’s efforts to exemplify an equation such as 2 + 2 = 5! High-performing teams require a complementary set of characteristics known collectively as “SCORE”—cohesive strategy, clear roles and responsibilities, open communication, rapid response, and effective leadership—as outlined in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 “SCORE” characteristics of high-performing teams

Characteristics |

Descriptions |

S: Cohesive Strategy |

High-performing teams with a cohesive strategy will demonstrate why they are in existence by articulating a strong, uniting purpose that is common to all team members. They will describe how they work together by defining team values and ground rules (also known as team charter that will guide the team actions). Finally, they will be clear about what they do by defining key result areas (KRAs). |

C: Establishing Clear Roles and Responsibilities |

Successful teams determine overall team competencies and then clearly define individual member’s roles and responsibilities. High-performing teams examine each individual’s responsibilities in terms of the key competencies of the role, resulting in an accurate understanding of each member’s accountability and contribution to the team. |

O: Developing Open Communication and Trust |

Communication is the key component in facilitating successful team performance; its lack limits team success. Effective communication includes flexing and adapting one’s style of communication to suit the other team members. In addition, a cohesive culture is attained when interpersonal interactions flow smoothly and individual differences are also respected and leveraged to enhance overall team functioning. |

R: Rapid Response to Problem-Solving and Decision Making |

A high-performing team responds quickly, as necessary, to changes in the environment, by shifting its members’ mental models with creativity and “outside-the-box” thinking. When faced with a problem, these teams brainstorm possible solutions and create innovative resolutions leveraging on NextGen leadership competencies, including cognitive readiness and critical thinking skills. |

E: Exemplary and Effective Leadership |

An effective team leader is able to adjust their leadership style (leveraging on Results-Based Leadership and Situational Leadership Frameworks) as necessary depending on the task at hand and the skill level of each team member performing that task. The team leader also demonstrates effective emotional and social intelligence skills as well as plays a critical role in raising team morale by providing positive feedback and coaching team members (managerial coaching skills) to improve performance. Finally, the team leader takes an active role in guiding the team through each stage of team development by using team-building activities and celebrating successes. |

In high-performing teams, leadership shifts during the stages of team development on the basis of team needs. Unlike organizational leadership, which remains somewhat constant, team leadership can shift from very directing, when the team is being formed, to more delegating, when the team is functioning effectively. When you have assessed your team’s current performance level and needs, you will be ready to move on to building your dream team in whatever SCORE category you choose to begin.

Case Study: Turnaround of a Highly Dysfunctional Team

A leading Fortune 500 information technology (IT) company dispatched a team of highly qualified and experienced IT engineers to deliver a large-scale strategic project for one of their clients in the mobile telecommunications industry. Sustaining market leadership for this client was critical to the success of this organization. However, high employee turnover, especially among the mission-critical talents, had created misalignment in what was once a strong performing team. Moreover, as competitors encroached, relationship management was critical with this strategic account. All this transcended the sound technical expertise of the IT engineers who demonstrated that a primary form of communication was e-mail. There was a lack of direction and clarity on the respective project team members’ role and responsibilities compounded by the relatively ineffective team communication, which resulted in frequent conflict leading to poor performance and results.

The SCORE framework was introduced through the facilitation of a series of team effectiveness meetings and workshops; the project team achieved breakthrough results in customer satisfaction and enhanced company, employee, and operational values. The team’s key performance indicators (KPIs) were achieved with shortened response times and improved communication project delivery within the allocated budget.

The team’s emotional intelligence was enhanced and relationship management became second nature as team members became more expansive, leading to the early exploration of new business opportunities. A post–customer satisfaction survey confirmed the acknowledgment of the value that the client provided to its customer.

Finally, the organization preserved its strategic account and strengthened the customer relationship, thereby sustaining market leadership. The project team’s ultimate proof of transformation was its unanimous decision to distribute among all team members annual performance bonuses previously assigned to a select few. This presents some evidence that high-performance teams impact not only the organization and marketplace but above all the gratified individuals that constitute them.

Best-Practice Toolkit: The Five-Step “AGREE” Framework to Achieve Collaboration

The CEE has developed the five-step AGREE process (see Figure 6.3) for achieving commitment to collaboration at the workplace as well as resolving conflict and negotiation situations driven by the use of communication skills.

Figure 6.3 The “AGREE” framework to achieve team collaboration

A: Acknowledge

The critical first step in achieving collaboration or resolving conflict is for all parties to acknowledge that a conflict exists. This is particularly important when any of the involved parties prefer a management style that is characteristic of conflict avoidance. Acknowledging that a difference in the way of working or conflict exists and inviting parties to collaborate help set the tone for a productive interaction.

Example: “I sense that we see this issue very differently, and I believe it is an important matter. Would it be helpful, from your perspective, to spend some time focusing on this? Who else should we involve to help us find a workable solution or work toward resolving this?”

Ground rules help establish the tone, climate, and time frame for a discussion toward a collaboration process. By establishing rules upfront, the parties begin negotiations with clearer expectations and a greater degree of comfort.

Examples: Listen to understand. Question to clarify. Maximize participation. Silence means assent. Speak for yourself. Be respectful.

R: Reality

Establishing the context and understanding the current reality related to the issues or conflict in question is the most critical step in achieving collaboration. It is used to move from the destructive side of collaboration (blame or winning at the other person’s expense) to the constructive side (resolving problems). In this phase, each person or stakeholder clearly articulates their understanding of the other person’s position and must consciously put any emotion aside and reconsider the situation from all perspectives.

Example: “If I am understanding you correctly, you are saying. . . .”

E: Explore

People rarely see a need for numerous options because each party already knows the right option, which is their own position. Brainstorming and exploring multiple options gives parties room to negotiate and support a problem-solving focus. The goal is to create as many options as possible that are responsive to the interests of all parties.

Example: “What do you think are the possible alternatives to resolve this challenge or issue?”

E: Execute

Sometimes the best option is readily apparent and satisfactory to all parties and the decision is made. More often, the parties select those options with the most potential and continue to explore them. Use of relevant objective criteria provides an independent basis for decision making by avoiding the will or power of either party. Once the best solution has been identified and agreed upon, the final step will be to implement or execute it effectively. Have a follow-up discussion regularly to enhance the collaboration.

Example: Possible objective criteria include cost, timeline, and customer demand.

Conclusion

The success of a team should be measured at regular intervals so that team spirit can be encouraged, either through celebrating achievements or through sharing problems. In terms of measuring success, it is perhaps easier to gauge the progress of a sports team than it is to rate the performance of work-based teams; for example, the performance of a sports team can usually be tracked by league tables.

Working as part of a successful team makes work enjoyable. It provides employees with a supportive work environment and enables them to address in a constructive way any conflict that might arise. In high-performing teams, leadership shifts during the stages of team development on the basis of team needs. Unlike organizational leadership, which remains somewhat constant, team leadership can shift from very directing, when the team is being formed, to more delegating, when the team is functioning effectively. To transform into high-performance teams, easily implementable frameworks such as SCORE and AGREE can help with achieving that end goal.