9

Principle of Equality

Introduction: Equity, Equality and Egalitarianism

In the last two chapters, we have discussed principles of liberty and rights. Individuals require rights and liberties for self-realization, development of human faculties or for self-mastery and carrying out their actions rationally and freely. Rights guarantee liberties and set limits of intervention by public authorities in the actions of the individuals and groups. For example, freedom of speech also means freedom of press and this puts limits on public authorities in regulating press. Liberty and rights, however, necessarily lead to a third principle in political theory, which is of equality. Equality determines how rights are to be distributed amongst the individuals as citizens and groups, whether equally or unequally. If unequally, then what are the grounds for unequal treatment? An answer to this makes equality an important factor in distributive justice.

Principle of equality also provides a framework of how the state or public authority defines its relationship with the individuals, citizens and groups. On what grounds the State or the public authority relate with citizens, individuals and groups unequally. When we talk of equality, we imply different meanings at different times. The important aspect is that different dimensions of equality (economic, legal, social, political, natural and gender) affect each other and insistence on one dimension or the other depends upon the perspective one adopts. In the liberal perspective, legal and political equality may be emphasized more than, for example, economic equality. On the other hand, in a socialist and Marxian framework emphasis is more on economic equality. A feminist would argue that gender equality is vital while in a caste divided society like India, it could be argued that social equality is more essential, if other dimensions are to be meaningful.

Equality, which means state of being equal, is derived from the Latin word, aequus/aequalis, meaning fair. It signifies ‘having the same rights, privileges, treatments, status and opportunities’. Equality is treated as something that relates to distributive principle because of which rights, treatments and opportunities are distributed amongst the beneficiaries in a fair manner. ‘Fairness’ however does not mean all to be treated equally in all circumstances. In fact, it very well means unequal treatment for those who are unequal. Essentially, it relates to the principle of justice because justice requires fair distributive principle. However, justice also demands that those who are equal should not be treated as unequal and the unequal as equal. This means distributive justice requires a principle of equality in which unequal distribution is effected to ensure the principle of equality. For example, the state should not tax a poor and a rich equally or it should not have the same policy of entry criteria for public employment for a normal and a physically challenged person.

Equality is also at times compared with equity, which has its origin in the same Latin word, aequus meaning fair. However, equity has come to signify fairness of actions, treatments, or general conditions characterized by impartiality, fairness and justice. Generally, equality is considered as a substantive principle while equity as procedural; equality is understood in terms of result, equity in terms of process. For example, equity requires that everyone should have equal opportunity of employment or education or being represented while seeking justice or defending one's right in the court of law. However, this in itself may not translate into equal employment or equal education or equal representation. This may happen because of the absence of or lack of conditions that otherwise would have enabled equal opportunity being translated into a substantive result. For example, as a landless poor person, I have neither adequate education nor certain employment. But as a citizen of India, I have the right to move freely throughout the territory of India and also to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India [Article 19 (d) and (e)]. I decide to exercise my right as a citizen and migrate to Delhi for employment. After all, I have to survive, as I cannot commit suicide, which is a crime in law. Imagine the fate, an uneducated, unemployed individual not entitled to commit suicide has reached the capital! Since I do not have enough money to buy a ticket, I decide to travel ticketless; since I have no place to reside I start staying under an over bridge and since I cannot feed myself but by stealing bread from a shop, I do that frequently. These are all crimes punishable by exemplary grace of the law. How, otherwise, am I suppose to exercise my right provided by the Constitution of India? What Constitution provides is procedural equality, that you will not be obstructed from exercising your right provided you have means to do that. However, if means are lacking—money to buy a ticket, place to reside in Delhi or money to buy food, equality of opportunity is mere procedural not substantive. In this context, we can say that there is no equality of right between a poor individual travelling ticketless, sleeping under a bridge and stealing bread from a shop and a rich individual who stays in a farm house, moves in a big car (though he does not pay tax because he is a farmer and we respect farmers as they are the backbone of the food security) and eats in a five or may be seven star hotel. It was this dilemma that the French novelist, Anatole France ridiculed in his The Red Lily. He ridiculed the ‘equality of the law which forbids the rich and poor alike to steal bread and to sleep under bridges.’1

Egalitarianism, derived from French égalite or égalitaire, i.e., equal, is the belief that all people should enjoy equal social, political and economic rights and opportunities. Egalitarianism believes that equality is the primary political value and it encompasses a variety of positions that argue for equality. However, neither equality nor equity nor egalitarianism advocates uniformity. Uniformity derived from the French word uniformes, means ‘having one form’ or being the same as one another, identical or of similar quality, characteristic, etc. Equality is about distribution or apportionment of rights, opportunities or outcomes and not about sameness or uniformity. Equality as a political principle is related to distribution of political, economic and social values and is linked with the conception of justice.

Formal Equality, Procedural Equality and Substantive Equality

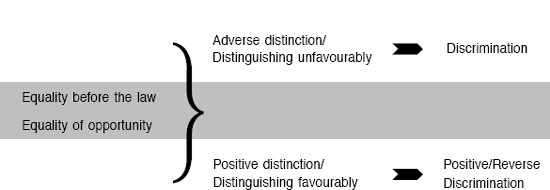

Equality is fairness in distribution or apportionment of political, economic, social and legal values such as rights (e.g. right to information or right to vote), opportunities (e.g. opportunity to education, employment, etc.), or outcomes (e.g. equal wage for equal work). Equality can be procedural or substantive. Procedurally, equality stands for equality of opportunity irrespective of the outcome, for example, equality in getting employment or education. Substantive equality stands for equality of outcomes, for example, equality of wage between male and female for equal hours of work. Equality may also be understood in terms of ‘equality before law’ or ‘equal protection of law’, i.e., law treats everyone equally irrespective of caste, class, religion or race. This is formal equality. As such, we have three types of equality—formal equality, i.e., ‘equality before law’, procedural equality, i.e., ‘equality of opportunity’ and substantive equality, i.e., ‘equality of outcome’.

Formal Equality

Equality has meant different things to different people in history. Its meaning has changed accordingly. For example, as Emile Burns says, ‘In the Greek city states, the idea of the equal rights of men did not apply to slaves.’2 Similarly, the slogan of ‘equality’ contained in the French Declaration appropriately meant equality of the rising capitalist class with the lords and the landed gentry. Equality as a principle found its place in the French and American Declarations. This is in the sense that ‘men are created equal’ or ‘are equal in rights’. This equality is based on natural rights theory where inalienable rights and their equal availability to all men are supported. Equality is supported because the rights available naturally are to be equally available to all. Equality is treated here as an endowed value and is supported based on very essence of human beings. Equality is equality of endowed natural rights. Heywood terms this as ‘foundational equality’, which he says, means ‘people are equal by virtue of shared human essence.’3 In other words, each person must be treated equally because of their essence as human beings and as carrier of natural rights. Initially, foundational equality was not understood in terms of equal opportunities. Thus, natural rights assumptions imply that they are available equally to all human beings.

A second meaning of equality in the formal sense, relates to ‘equality before law’. Legal equality of persons/individuals is based on the conception of juristic personality. Bentham used the Utilitarian principle to argue for legal equality—’everyone is to count as one and nobody as more than one’.4 He sought to subject the principle of equality to the criterion of the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Moreover, to judge the greatest number, it requires each individual being treated as having equal worth in terms of utility. Bentham supported legal equality for the purpose of legislation that should be based on the principle of utility. Bentham and other jurists who gave primacy to law as the source of rights and liberty advocated equality in legal terms.

If this were the case, we can also infer that each being counted as one implies that gender or any other social differentiation is immaterial for consideration of equality. Utilitarian principle is easily a ground for gender equality, but probably it was not so vocal. In fact, J. S. Mill in his essay, The Subjection of Women, argued for gender equality and provided a statement of liberal feminism. Mill argued that ‘male and female endowments or natures are uniform, and observed differences between the genders altogether (are) cultural in origin.’5 He gives a clear statement of the need for gender equality. He says, ‘the principle which regulates the existing social relations between the two sexes—the legal subordination of one sex to the other—is wrong in itself, and now one of the chief hindrances to human improvement; and that it ought to be replaced by a principle of perfect equality, admitting no power or privilege on the one side, nor disability on the other.’6 In Mill, we find a principle of equality, which admits legal equality irrespective of gender. If we take into account the argument of natural rights as equally available to all irrespective of gender, Bentham's argument of equal worth of each individual and Mill's argument of gender equality, there is no ambiguity as to why equality amongst genders in terms of voting rights, equal wages, etc. should have taken so long to be realized. Natural rights theory, Utilitarian doctrine and Mill's liberal feminism, all provide sufficient philosophical and moral foundation for gender equality.

Equality before the law as a principle of formal equality is a legal concept. It admits no distinction amongst individuals on cultural, gender, linguistic, natural, racial, religious, social, other such grounds. Utilitarian, Bentham and analytical jurist, Austin provided a strong ground for legal equality as a concept. The juristic concept of sovereignty as a source of law, rights, liberty and legislation involve that legal equality of individuals should be admitted as the principle for defining the relationship between the state and the individual. In fact, equality before the law provides a legal framework through which equality in distribution of rights (as Charter or Bill of Rights) or Fundamental Rights amongst individuals is ensured. It also helps regulate the conduct of individuals as well as the state and its officials. Rule of law is closely associated with legal equality and it means law should rule. Under rule of law, ‘law establishes a framework to which all conduct and behaviour conform, applying equally to all members of the society, be they private citizens or government officials.’7 Law secures equality of all while dealing with an individual.

The Indian Constitution under Article 14 provides for ‘equality before the law’ or the ‘equal protection of the laws’ to all persons. This is a statement of formal equality and gives meaning to what Preamble seeks to ensure in terms of ‘equality of status and of opportunity’.8 This also means that laws of the land will apply to all equally and there should not be discrimination on grounds of birth, caste, colour, gender, language, race, religion, etc. In fact, Article 15 of the Constitution substantiates Article 14 further by prohibiting any such discrimination. Equality before the law and equal protection of the law have been further strengthened in the Indian Constitution under Article 21. It ensures that ‘No person shall be deprived of his (her) life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law’. This means that a ‘reasonable, fair and just’ procedure should be followed for depriving a person of his/her personal liberty and life. It admits no arbitrariness, discriminatory procedure or unequal treatment for different individuals.

However, formal equality, though important, does not necessarily translate into either equality of opportunity or equality of outcomes. This may happen due to two main factors. One, many socially, psychologically, behaviourally and culturally institutionalised customs or attitudes would continue to deny such equality, and second, in the absence of economic and material conditions, formal equality may never be translated in outcomes. Despite formal equality in terms of equality before the law, culturally determined attitudes of men towards women in many parts of India, or for that of persons of one religion or language or caste towards that of the other still could be different than desirable. Secondly, lack of material and enabling conditions hampers enjoyment of formal equality, as one cannot translate the opportunities in reality.

Procedural Equality

Equality of opportunity relates to initial conditions or circumstances with which people start and seek various facilities, rights and outcomes. Equality before law or equal protection of law provides legal conditions of enjoying equal access to various facilities and means. Formal equality implies equality of human beings as possessor of rights and liberties or equality before law as juristic personality. On the other hand, equality of opportunity relates to level playing field in initial conditions or circumstances. In this way, it is not merely a matter of equality before the law, but also provision of such initial conditions, which help start on equal footing. For example, if education is important for employment, equality of opportunity of employment necessarily requires that there is corresponding equality of education. If there is no equal access to education, the equality of opportunity to employment is no equality.

At times, equality of opportunity may lead to the opposite of what formal equality requires. Formal equality requires equality before the law or equality of human beings. However, equality of opportunity requires that everyone should have an equal starting point, irrespective of results. In this, it is not enough to say that a child who has money to get admission in a school and a child, who does not have, enjoy the same equality of education. To the extent that there is no explicit prohibition on a particular ground, equality of the law gives equality of access. This may be formal equality. On the other hand, equality of opportunity demands that both the children at least should start on equal footings in terms of admission in school. If one does not have money to get admission, a level playing field requires that assistance of the State should be given. Advocates of equality of opportunity maintain that this is required primarily because social, economic and other existential circumstances facilitate some to start much ahead of others. Many lag behind not because of their natural talents and intelligence but because of their initial conditions.

Equality of opportunity, in essence, requires that there should be state intervention to mitigate certain initial inequalities which arise due to various factors: (i) social inequality such as caste and other forms of discrimination, (ii) economic inequality including inheritance and property rights, (iii) geographical location such as urban or rural location, (iv) family background such as educated or uneducated, etc. Without any prejudice and only as an illustration, let us take an example. Is there equality of opportunity between the son of a rich person having inherited his father's property, employed with a multinational corporation and settled in Delhi with the son of a landless poor person, seasonally employed and settled in a remote rural corner of India? Have the two equal opportunity to get education or employment unless there is external assistance for the second?

It is generally recognized that a liberal constitution will neither abolish inequality of property nor inheritance. In such a condition, the option available to ensure equality of opportunity is to adopt a policy of positive discrimination. Positive discrimination is also known as reverse discrimination or affirmative action. This means discrimination amongst those who are unequal to ensure equality of opportunity. It implies that if those, who are unequal, are treated equally as formal equality requires, it will lead to inequality. Here, equality of opportunity implies compensating for initial inequalities. In India, Article 15 of the Constitution prohibits discrimination on grounds such as race, caste, sex, etc. and Article 16 provides equality of opportunity in matters of public employment. However, both these Articles have exceptions to their general provisions and ensure positive discrimination for women, children, socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in education, employment, public offices, etc. Apparently, this is in recognition of the social injustice that prevailed historically in caste terms. In USA, positive discrimination or affirmative action has been adopted against the racial discrimination of blacks. Equality of opportunity relates to compensating for inequality arising either due to social, historical or economic disadvantages. It seeks to ensure that initial starting point provides equality and level playing field. However, it is not concerned with equality of outcomes.

Substantive Equality

Substantive equality or equality of outcomes may be treated as a very radical end of egalitarianism. While formal equality seeks legal equality and procedural equality seeks equality of initial circumstances, substantive equality looks for equality of outcomes. While equality of opportunities is concerned with initial conditions, equality of outcomes is concerned with results. Equality of outcomes may be of resources such as education, employment or equality in material and welfare terms such as wages, living conditions and other welfare outcomes. Most of the welfare measures and redistributive policies of the governments in terms of social and welfare policies are intended either to provide equality of opportunity or equality of outcomes. For example, equal wage for equal work seeks equality of outcome for both male and female; reservation in employment and education for socially and educationally backward sections in society is aimed at providing equality of opportunity.

Many have argued that desire for equality of outcome is ill-founded. This is because equality of outcomes is against basic human differences in talent, skill, aspirations and desires. This is also undesirable as it would be travesty to treat equal, unequally and unequal, equally, as Aristotle would say. The Marxian perspective would argue that substantive equality can only be achieved based on economic equality and that can be achieved only in a socialist society.

A Brief History of Equality and Inequality

Historically speaking, concept of equality or inequality has been always debated. While Plato thought of and advocated inequality originating in the form of three classes—representing the philosophic mind, the courageous spirit and the acquisitive stomach, Aristotle emphatically argued for slavery as representing accumulated wisdom of generations. Equality, as we understand today, was not the same during the Greek, Roman or the medieval times. As Emile Burns says, equal rights of men did not apply to slaves in Greek times.

Sabine is of the view that it was the idea of harmony or proportion, which was fundamental in the Greek idea of the state. The idea of harmony or proportion was a measure of civil quality and equality might not have been the concern. As we know, even Aristotle, who defended slavery, argued for balanced city-state and extolled the virtue of middle class as one of balancing factor between extremes of richness and poverty. However, this was more due to the concern for proportion or harmony than equality. On the other hand, Greek society had no dearth of those who supported equality amongst men. Significant amongst them were statesmen and literary persons such as Pericles and Euripides and schools of the Sophists including Antiphon and the Stoics. Euripides (Greek tragic dramatist, 480–406 BC) in his Phoenician Maidens makes Jocasta say, ‘Man's law of nature is equality’.9 Sophists denied the assumptions that slavery and nobility of birth were natural. Orator, Alcidamas protested against slavery and inequality and stressed that ‘God made all men free; nature has made no man a slave.’10 In the third century BC, Stoics led by Zeno and Seneca argued that human beings possess reason and are united without any difference. On this basis, they advocated natural equality of all men and opposed slavery.

Rome's famous statesman and political thinker, Marcus Cicero (106–43 BC), who was a senator, advocated a composite state consisting of the three elements—the monarchical element represented in the consuls, the aristocratic element or patricians represented in the senate and the plebeians or the common people represented in the tribunes. Like Aristotle's polity with a predominant middle class as a balancing factor, Cicero's composite state is also aimed at providing a balanced Roman state as a solution to class differences.11 Instead of equality, balancing different class elements was the focus of both Aristotle and Cicero. As such, idea of proportion was given more importance than the concept of equality. However, equal participation by free men in public life was considered a virtue. The Greek extolled it and the Romans struggled for it. In 212 AD, the famous Edict of Roman Emperor, Caracalla conferred Roman citizenship on all non-slave or free inhabitants of the empire.12 This was a significant concept in terms of political equality in an empire, though by no stretch of imagination like what we understand of political equality today in a democratic state.

During the Roman period, slavery was the important source of labour. Slavery manifested in many forms including the gladiatorial activities and its promise of liberation. Spartacus, a Roman slave and a gladiator in Capua before being suppressed in 71 BC and his thousands of men killed, had rebelled and headed a slave insurrection in 73 BC in southern Italy. He advocated equality based on the colour of blood of all men. In fact, Spartacus's revolt, which is known as the Third Servile War, was the third in the series of revolts of slaves. In 134 BC, the leader of slaves, Eunus, led the First Servile War in Sicily, which was suppressed in 132 BC. Two other leaders of slaves, Tryphon and Athenion, led the Second Servile War in Sicily in 104 BC, which was suppressed in 101 BC.13

After the end of the Roman period, Christianity in Europe and Islam in Asia particularly, raised the voice for equality. However, this was mainly equality in terms of the religious affiliation and spiritual identity. As St. Paul said, ‘thou all one in Jesus Christ’ meaning that before God all are equal. This is like what Hobbes would say that the unity of the people consisted in the unity of the Sovereign or Leviathan. The unity of identity of the religious or spiritual community was the basis of equality. In Islam, the concept of universal Ummah based on equality of members promised a new perspective on equality. Nevertheless, equality in terms of the moral and spiritual consideration could not somehow suppress or root out economic and material inequalities that continued. Today, neither Christianity nor Islam can claim to have dealt with inequalities of its members. Variety of inequalities and differentiations continue. As such, religion as a moral and spiritual framework has not been able to provide a framework of material redistribution and hence equality as well. In fact, the very emergence of a movement in mid-eighteenth century in Europe and especially in Britain, in the name of Christian Socialism is a pointer to this. Christian socialism sought to commit the church to a programme of social reform and to help better the wretched condition of the working class. This was a pointer to the inadequacy of a mere religious-spiritual framework of equality. Christian Socialism acknowledges the importance of material factors as having ‘bearing on the ability to lead a truly religious life’.14

In India, inequality has historically manifested in terms of caste-based social hierarchy. caste-based social organization consists of Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra. They have been arranged in vertical hierarchy. There can be two sets of interpretations regarding caste-based social organization in India. One may tend to treat these castes as classes based on occupational categories. Brahmans or priests or wise men leading a life of teaching, study and devotion, spirituality and ethical and moral guidance to the society could be one class. Kshatriyas or those, who are assigned the task of protecting others, leading a life of courage and valour, make another class. Vaishyas who are mainly agriculturalists, artisans, cultivators and those who are engaged in trade and merchandise constitute yet another class. Shudras who are labourers and unskilled workers, other than agriculturalists, constitute the lowest class. Jawaharlal Nehru in his, The Discovery of India interprets castes in terms of occupational or functional classes.15 However, there can be a different interpretation of the caste-based social organization, which may treat these castes not by their occupation but primarily by the way they are conceived to have originated. Abu Raihan Muhammad ibn Ahmad, popularly known as Al-Biruni, in his book, Tarikhu’l Hind (Enquiry into India) mentions that Scriptures treat castes by their origin. ‘Brahmana has been treated as originating from the head of Brahman, Kshatriya created from the shoulders and hands of the Brahman, Vaishyas created from the thigh of the Brahman and Shudras created from his feet.’16 Manu's Dharmashastra (The Laws of Manu) also known as Manusmrti, does provide an elaborate description of all.

Notwithstanding different interpretations about the caste system, at the bottom of this caste hierarchy, there is convergence in terms of economic and social deprivation. A member of an underprivileged caste invariably, also had been a member of the underprivileged class. Caste and class inequalities have coincided in such situations. Shudras in India represent a convergence of caste and class inequalities. Of particular attention is the practice of untouchability within the caste system, which prescribes rules of interaction, distance, pollution and social intercourse between the members of the upper castes and the section of Shudras categorized as untouchables. The practice of untouchability can be termed as a novel innovation of human mind in the history of inequality. It treats even casting of a shadow or touch of one human being to another as polluting, leave alone any meaningful social interaction. Untouchability has been a practice of not only social inequality but also of social exclusion.

In Europe and in India also, the medieval period is associated with feudalism. Feudalism is characterized by privilege and status-based social and economic order. Hierarchical order based on privilege, status and chain of obligations resulted in sub-infeudation and unequal socio-economic order. Feudal lords and serfs in Europe and zamindars and peasants and landless workers in India became the opposite classes. In Europe, clergy, nobility and aristocracy were the privileged classes and the rest of the people were treated as commoners and labourers. Privileges and status were based on birth and inheritance. In Europe, privileges to one group or class were against the interests of the other. The nobility, the vassal and the clergy had their respective privileges. In fact, political power and affairs of the state were also a matter of privileges. There was no concept of citizenship in either medieval Europe or in India. However, amidst the celebration of privileges, there were various uprisings by the oppressed peasants. It is reported by Braudel that there were various peasants’ uprisings in France (Jacquerie in 1358, Paris in 1633, Rouen, north-western France in 1634–9, Lyon, eastern-central France in 1623, 1629, 1633 and 1642) and in Germany (in 1524–5). The conditions of peasants in Europe during feudalism could be understood when we look at the plight in Bohemia where they were allowed to work on their own land only one day in a week, in Slovenia where they could work only 10 days in a year. The feudal system and its system of bonded-service had no place for equality for all.17

Post-Renaissance Europe witnessed a demand for various forms of equality—social, political, legal and economic. One can argue that emergence of liberal-democratic ideas of individual liberty and rights and the concept of contract have contributed to the conception of equality—legal and political. This provided a break from the medieval privilege and status-based socio-economic order. Emergence of the commercial and mainly the industrial class challenged the power and privileges of the feudal classes in Europe. However, the American Declarations of Independence and the French Declaration of Rights were declarations of equality of the rising bourgeois class with the landed and aristocratic class. The 1789 French Declaration which declared that ‘Men are born, and always continue, free and equal in respect of their rights’, though landmark in the history, only promised the equality of liberty of the emerging capitalists with that of the landed bourgeoisie. The peasants at land and the working class of the emerging industrial economy were still to fight for their equality. Socialist movements in Europe in the nineteenth century brought to forefront the demands for economic equality that the liberal-capitalist framework had so far ignored. The socialist movements were declarations of the equality of the working class with the rest.

During the eighteenth century in Europe, various thinkers and writers advocated and argued for equality. Jean Jacques Rousseau, for example, in his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality maintained that rise of property ownership and possession led to the conception of ‘mine’ and ‘thine’ and contributed to the emergence of inequality. He drew a distinction between natural and conventional inequalities. While natural inequality (or natural differences) being physical is beyond one's choice, conventional inequality arises out of inequality of wealth, power, resources and privileges in civil society. Conventional inequality being a product of social arrangements should be dealt with. Rousseau feared that ‘material inequality would lead, in effect, to the enslavement of the poor and deprive them of both moral and intellectual autonomy.’18 Rousseau celebrated the genius of man and his innate goodness and protested against slavery. He said that to decide that a son of a slave is born a slave is to decide that he is not born a man. Though Rousseau and others such as Condorcet supported equality amongst humankind, equality as a principle of economic organization did not have its firm root at that point of time. Condorcet as a philosopher of ‘progress’ believed that progress would follow such a line in which ‘the elimination of class-differences’ would also occur. Explaining further, Sabine opines that Condorcet expected that ‘within each nation it is possible to remove the disadvantages of education, opportunity, and wealth which inequalities of social class have imposed on the less fortunate.’19 Comparing Rousseau and Condorcet, we can say that while Rousseau gave a critique of progress to oppose inequality, Condorcet used progress as an argument for bringing equality.

Seventeenth-eighteenth century doctrine of natural rights and social contract had given a concept of civil and political equality of men. Social contract implied equality of all to enter into contract and enjoy equal political rights. The concepts of natural rights, contract, consent, limited and representative government, citizenship, etc. laid the foundation for political equality. However, this was limited to the emerging capitalist class, and that too, to the men. It was J. S, Mill, in the nineteenth century, who introduced an element of caution. He pointed out the danger of majoritarian tyranny standing in the way of smooth operation of political equality where majority suppressed the minority's political view. Alex de Tocqueville, whose famous work Democracy in America (1835–40) focused on development of democracy, was of the view that ‘its (democracy) main tendency was to produce social equality, by abolishing hereditary distinctions of rank, and by making all occupations, rewards and honours accessible to every member of society.’20 However, Tocqueville felt that at times passion of democracy with social equality might be harmful to liberty of individual. In this context, he found equality and individual liberty in conflict.

The nineteenth century is particularly significant for two reasons. On the one hand, analytical jurists and legal theorists, such as Jeremy Bentham and John Austin, provided arguments for legal equality, on the other hand, socialist thought led by Karl Marx pitched for economic equality. Bentham's utilitarian principle of each as one (in counting the greatest happiness of the greatest number) provided the legal basis for social legislation. The need for legal equality was given primacy because the rising bourgeois class needed legal protection for securing parity with the nobility and landed aristocracy. Economic equality was never a requirement of this class, as industrial and commercial ownership provided economic power. Socialist thought, in the shape of the Marxian doctrine, provided unequivocal demand for economic equality, as it was needed for securing the rights of the working class. It may be appropriate to mention here that the nineteenth century demand for economic equality could trace its link to what FranÇois Babeuf, the French revolutionary, is identified with—’Conspiracy of Equals’. Babeuf raised his voice for economic equality for the working men and planned insurrectionary activities21 before he was killed in 1797.

R. H. Tawney, a British social philosopher, in his book, Equality (1931), has discussed the primacy given to legal equality over economic equality during the nineteenth century in Europe. He has also argued that equality and liberty are compatible. Eighteenth-century Europe was mainly concerned with legal and political equality. This was important because demand for legal equality enabled the rising capitalist class to fight privileges enjoyed by the aristocracy and nobility. Demand for political equality helped them seize the power of the state. As Tawney points out, the class system in France and Germany was characterized not only by disparity of wealth and income but also legal status.22 Wealth, in any case, was available to both the classes, it was legal sanction to the privileges that the feudal aristocracy enjoyed that made the difference. Tawney mentions that legal privileges of the feudal class were attacked first and demand for ‘uniformity of legal rights’ was raised.

However, it was only in mid-ninteenth century that revolution in France demanded economic equality. Formation of communes in the 1870s and the influence of the socialist thought triggered widespread voice for equality. The Marxian thought raised the issue of economic equality and the associated question of abolition of private property. Other movements—Syndicalism and Guild Socialism, did favour and fight for economic equality. The ninteenth century also witnessed demand for political equality for those who were hitherto excluded from voting rights. Prominently, demand for equality in terms of extension of right to vote for women came up. In July 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized a women rights’ convention in New York, which demanded equality of right to vote for women. The convention also demanded property rights, admission to higher education and church offices, on equal terms.23 Political equality in terms of voting rights to all, equal right of all to hold public offices, and equality of citizenship evolved in three stages. Firstly, the bourgeois class secured political equality vis-á-vis landed aristocracy; secondly, the working class demanded political equality against the privileges of the capitalist classes and thirdly, women demanded political equality. An important event in the ninteenth century was the abolition of slavery in America through the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1965. The question of economic equality witnessed its stronger voice in communist revolutions in the early twentieth century.

In the colonial relations with the British Empire during the ninteenth and the first half of twentieth century, Indian people did not have political rights and the question of political equality did not attract much attention. Demand and struggle for self-government and political rights for Indians was a long drawn and gradual process. The concept of citizenship was absent and Indians were in a colonial relation with the British power. However, with measures in the field of social legislation and workers’ related legislations, the British introduced a framework of legal equality amongst the Indians. Uniform legal codes (CrPC, IPC, etc.), social legislations and other such measures introduced a framework of legal equality. It was only after the introduction of the Constitution of the Republic of India in 1949 that the concept of political, legal, social and to some extent, economic equality could be enshrined.

In the twentieth century, struggle for equality has manifested in different forms. Demand for civil, economic, political and social equality has been raised all over the world. Socialist revolutions in Russia, China and many other countries in the early part of the twentieth century were the culmination of the concept of economic equality. The Constitution of India abolished the practice of untouchability and made it a punishable crime. This is a measure of social equality. In Africa, the white-dominated National Party enforced a state policy of racial segregation and discrimination against the black inhabitants. This policy of racial segregation and discrimination between the white and the black is known as apartheid (Afrikaans word meaning ‘apartness’). It was based on racial purity and white supremacy. Led by Nelson Mandela, black resistance to apartheid regime continued until the 1990s. After the African National Congress (ANC) took over the government in 1990s, apartheid was abolished. Abolition of untouchability in India and apartheid in Africa has provided equality in terms of human dignity and access to other social and material resources. In the post-Second World War, Martin Luther King, the black civil rights activist, led the struggle for civil rights to blacks. They fought against what he says ‘manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination’.24 The twentieth century has also witnessed struggle for gender equality. Gender equality in terms of equal rights to vote, empowerment in terms of inheritance, employment and public offices, sexual freedom, etc. has been sought. In India, the Constitution provides gender equality in all aspects of social, political and public life. Various measures have been initiated for empowerment, such as certain level of ensured representation in public offices in local level governments, tax-related exemptions, coparcener in inheritance, protection in terms of civil rights, etc.

Meaning of Equality

Our survey above helps us: (i) differentiate between equality and other similar concepts such as equity or identity of treatment, proportion or balance, uniformity, etc. (ii) make a distinction between formal, procedural and substantive equality; and (iii) locate different dimensions of equality such as civil, economic, gender, legal, natural, political, racial, social, etc. Equality is an important political ideal that has been used to determine how rights, liberties and various publicly available resources such as welfare and social benefits would be distributed amongst the people. Equality is principle of such a distribution, both for individuals and groups. However, equality does not mean merely equity or uniformity of treatment or similarity in appearance or being identical. Both Laski and Tawney recognized complexity of the issue involved in defining equality in a precise manner, as it contains more than one meaning. Rousseau's differentiation between natural and conventional inequalities meant that certain forms of inequalities are beyond human regulation but some others are a creation of civil society. Equality has been demanded at different stages of history involving a variety of justifications. Stoics argued for natural equality of human beings; Spartacus raised a voiced for equality based on colour of blood; equality of birth has been argued for seeking parity with those who claimed superior birth; anti-slavery, anti-apartheid, anti-untouchability movements invoked the criteria of human dignity; the socialist and communist movements demanded ownership of means of production as measure of equality; and in contemporary times, we have active demand for gender equality irrespective of naturally and biologically conditioned differences.

There can be differences in the emphasis on the ideal of equality. This could be due to the socio-political and economic organization. For example, in a liberal-capitalist society, equality would mean equality before law and at most equality of opportunity. It concentrates more on equity in the sense of fairness of action and procedures, chances and opportunity. It is not concerned with equality of outcomes or results but only equality of opportunity. R. H. Tawney was critical of the concept of equality of opportunity and termed it as ‘tadpole philosophy’. According to this, ‘all may start out from the same position but then left to the vagaries of the market; some will succeed but many will fail.’25 Slightly different from the equity-based idea of equality could be welfare-based arguments. Welfare state would generally address the issues related to redistribution of not only initial chances but also the outcome or results. It is observed that equality of initial conditions or a fair play or level playing field in the beginning, may also lead to inequality of results. A welfare state seeks to take care of those who are left behind due to variety of factors such as the operation of free and private players, difference in skills and talent or may be physical and mental challenges. A welfare state seeks to employ equality of outcome arguments or at least redistributive arguments to avoid extreme inequality of results. On the other hand, in a socialist society, social ownership of means of production seeks to remove economic inequality by the means of social ownership of resources, chances and offices. Here, equality is not sought as a matter of procedure and opportunities, but by social ownership of means of production. However, some may argue that socialist countries seek economic equality at the cost of other ideals or principles such as political rights, civic freedoms, etc.

Within the liberal fold, there is a pluralist position, which argues for autonomy of and equality amongst various groups, the State not being an exception. It argues for group autonomy and accordingly for recognition of individuals as members of these autonomous groups. This means individuals affiliated to different organizations, associations and groups could be treated differently if parity amongst various groups is to be maintained. For example, an individual as a mosque or temple or church-goer requires different rights and liberty than he or she requires as a lawyer, doctor or as painter or dancer. For a pluralist, State and other social, religious, political, cultural and professional associations should be treated at par for the purpose of their control and regulation over individuals. Another school supporting the multicultural perspective argues that there may not be need for the State to relate to all its citizens based on equality of treatment. This is because, it argues, to bring individuals belonging to or having affiliations with different cultural, social and religious backgrounds into the mainstream of political and social processes and the public domain, all must be treated as having different identities.

An important consideration for the concept of equality in modern times has been treating individuals as citizens in a democratic set-up. The State and public authority treats individuals as equals and applies all laws and rules of the state equally to them. Extension of franchise to all eligible adult citizens, application of rule of law to all, equality before law, equality of opportunity to all eligible candidates in the field of education, employment and holding public offices, absence of discrimination based on any socio-cultural identity in public places, etc. are a result of individuals identified as citizens and not as particular X, Y, Z. However, this does not exclude exceptions based on socio-cultural considerations. The basic thread of individual–state relationship is defined in terms of equality-based conception of citizenship.

Given different meanings attached to the concept of equality, it is difficult to define it precisely. Laski treats equality as a means to bring parity amongst the citizens so that no one's basic rights as citizens are denied. He says, ‘It (equality) means that my realization of my best-self must involve as its logical result the realization of others of their best selves.’ Laski speaks in terms of equality of conditions that citizens should enjoy for their self-realization. The same concern Rousseau also had voiced when he said that ‘no citizen shall be rich enough to buy another and none so poor as to be forced to sell himself’. In a utilitarian context Bentham's idea, that ‘every one is to count as one and nobody as more than one’ in deciding the worth of each and happiness of the greatest number, relates to equality amongst individuals. Equality is a conception, ideal or principle in political theory that also helps us decide how the relationship of each individual is to be defined in terms of the sharing of resources—economic and material, rights, or happiness. These resources are vital for either self-realization or human dignity or what Amartya Sen would call, ‘expansion of freedom’. This may involve equality before law, equal protection of law, equality of opportunity, equality of outcome, positive discrimination for ensuring parity, etc. Equality also means absence of special privileges to few.

R. H. Tawney holds that equality and liberty are compatible and argues that equality requires that liberty of others should be regulated because ‘freedom for the pike is death for the minnows.’ In this sense, equality means coordinated freedom for all and not complete freedom to few and absence of it to others. Tawney also echoes the view of Rousseau and Laski that equality means absence of extremes of capacity and incapacity.

To clarify the meaning assigned to equality as a concept, we may summarize the characteristics of equality as follows:

- Equality can be understood in positive as well as in negative sense: In a positive sense, equality means presence of enabling conditions, opportunities, and benefits that help equal enjoyment of rights by all. While equality in a positive sense envisages legal, political, economic and civil equality and the welfare state, equality in negative sense requires primacy of democratic values and social equality. Harold Joseph Laski, considering equality in negative and positive sense, describes equality as involving:26

- End of special privileges

- Absence of social and economic exploitation

- Adequate opportunities open to all

- Equal access to social benefits irrespective of birth and heredity

While conditions at (a) and (b) above are examples of equality in negative sense, (c) and (d) are examples of equality in positive sense. Equality, as such requires that whatever resources, rights and liberties the state makes available to citizens must be conferred in an equal manner. It does not admit conferring special privilege on some or discriminating against others. In other words, it implies absence of privileges to few and presence of opportunities for all. Further, to ensure that adequate opportunities are available to all including those who are impaired due to lack of material and economic resources or any other disability or incapacity, there could be provision for a level-playing field in the initial period.

- Equality neither means identical/niform treatment nor absolute equality: Equality does not mean absolute equality of each in all aspects. It also does not mean identical treatment to all. In fact, equal treatment of all would be the very negation of the conception of equality. It requires that equals must be treated equally and unequal unequally. Justice requires that those who are unequal should be treated accordingly for the purpose of distribution of rights and public resources. Tawney elucidates this aspects when he says ‘…the sentiment of justice is satisfied, not by offering to everyman identical treatment, but by treating different individuals in the same way insofar as, being human, they have requirements which are same, and in different ways insofar as, being concerned with different services, they have requirements which differ.’27

It would result in inequality if, say a person earning one lakh rupees per month and another earning Rs 20,000/- per month are taxed equally. Taxation in India, for example, is aimed at redistributive justice besides being a source of revenue to the government. In short, as Heywood says, for social democrats, equality is understood in terms of distributive equality rather than absolute equality. Generally, in liberal and welfare states, equality is advocated as a goal for equality before law or at the most, equality of opportunity. This means equality in terms of distribution of rights and access to various opportunities. In the Marxian framework, inequality is understood in class terms, which arises from private ownership of means of production. Abolition of private property, class conflict and bourgeois state could be the only basis for achieving meaningful equality. So search for legal, civil and political equality without social ownership of means of production is irrelevant.

A related aspect to the idea, that equality is not about being treated in identical or uniform manner, is the distinction between reasonable and unreasonable or morally or functionally acceptable and unacceptable inequality. We should not confuse the issue of equality as a principle of distributive justice with that of functionally useful differentiations and division of labour. There cannot be an argument on the fact that everyone is neither capable nor required to do the same thing nor does one need similar things. What is being insisted here is that despite all differentiations—inequality of merit, skill and talent and division of labour—political and social process in the end should not result in extreme of inequalities. As such, though reasonable distinction and inequality is accepted and in fact would be useful for society, justice requires redistribution to ensure extreme of inequalities do not occur. As history has taught, extreme of inequalities have always propelled revolutions and widespread social cleavages and disturbances.

Further, though absolute equality may not be the end, there are certain aspects of social and political life that in fact require concept of absolute equality to be adopted. For example, equality, which aims against racial and caste discriminations, or against gender bias could be pursued in terms of absolute equality.

- Equality as a principle of distributive justice: Equality is generally treated as an important aspect of justice. Further, equality is derived from the principle of rights. This is because if a set of rights have been provided to the citizens, principle of equality requires that they should be distributed in such a way that it does not result in advantage to few at the cost of disadvantage to some others. Equality before the law requires that when law or legislation provides rights or imposes duties, these rights and duties should be equally applicable to all. Unequal application is admitted when it serve the purpose of equality.

- Equality as a derivative value of the development of personality: Equality is thought as a desirable value and is prescriptive in nature. Prescription for treating all human beings equal, for example, comes on various grounds. One of the important grounds invoked is the dignity of human beings. All human beings possess reason and are rational beings. This means they all should be treated equally as far as distribution of rights is concerned. Ernest Barker in his Principles of Social and Political Theory treats equality as a derivative value, which, he says, is derived from the value of the development of personality. Development of personality implies that there is capacity inherent in an individual that needs to be provided with conditions for realization. According to Barker, each person is recognized as a legal personality and each legal personality is treated equal to every other legal personality. Thus, in law all legal persons are to be treated equal. The state seeks to ensure equal condition for making best of oneself by providing legal equality. It seems Barker suggests that by recognizing legal equality, the state in fact provides an equal chance to all individuals as moral persons for their self-realization. However, the outcome may eventually differ because of difference in what we make of ourselves. Barker feels that in a liberal sense, equality as a principle is concerned with equality of opportunity in the beginning and not equality of results. For example, all rights and conditions should be allocated equally, though it may happen that some using these rights and conditions can travel much ahead than others.

However, Barker recognizes that legal equality in itself is not sufficient and social and economic inequalities distort realization of equality in a legal sense. He mentions that legal equality has been followed by demand for political and economic equality. Political equality in terms of expansion of suffrage, right to hold public offices, etc. to a wide section of society including women has come true due to the spread of democratic ideals. Economic equality is sought to be achieved through, what Barker says, welfarism. He further opines that the welfarist principle relies on two economic methods to achieve economic equality: one, limiting accumulation of wealth by differential taxation of income, and second, by regulating and raising the wages of poor and workers and public expenditure. However, Barker acknowledges that economic equality in this sense is based on the policy of progressive correction of economic inequality to suit the cause of legal equality. As such, economic equality is not aimed at bring substantive economic redistribution through social ownership of means of production, as the Marxian position seeks.

- Equality as a principle of social engineering and revolutionary change: Historically, demand for equality, either legal or political or economic, has been associated with certain revolutionary changes. The rising capitalist class raised their voice for legal and political equality against the powerful landed and aristocratic elements. The Declaration of Rights of Man as culmination of the French Revolution and its slogan for ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ declared that ‘Men are born and always continue free and equal in their rights.’ It was the idea of equality—equality of the rising capitalist class with the nobility and aristocracy that propelled the revolution. Similarly, the voice of those who sought economic equality through social ownership of means of production and abolition of class conflict culminated in socialist revolutions. Equal rights to suffrage to women have also resulted in social change. Further, the idea of equality of outcome or equality of results means that the state would be required to interfere in social and political process, without which equality of outcomes would be difficult to achieve. This requires, what some reject as ‘social engineering’.28

Many thinkers support liberty and reject the claim of equality as inimical to liberty. Prominent amongst them are Hayek, Friedman, Nozick, etc., and they insist that search for equality of outcomes or results is inimical to liberty. They reject any social engineering for redistribution of resources and wealth that has been produced in a market situation based on individual talents, skills and abilities. On the other hand, positive liberals, advocates of welfare state and social democrats, such as Laski, Tawney, Barker and others support the idea of social engineering for achieving meaningful equality.

Dimensions of Equality

In our brief survey of history of equality and inequality, we have located various dimensions of equality such as civil, economic, gender, legal, political, racial, social, etc. One may also add natural equality as one more dimension as it appeared in the declarations after the American and the French Revolutions. By dimension of equality, we mean the aspects or spheres in which equality could be possible or is demanded for. No one demands or agitates for equality of physical appearance or equality of religious dispensation that all religions must worship the same God or in the same manner, etc. This means there are reasonable expectations for equality in certain aspects and reasonable acceptance of inequality in certain others. We will discuss briefly various dimensions of equality, their justification, evolution and relevance for political ideal of equality.

Civil Equality

The word civil is derived from the Latin word civilis or civis, which stands for citizen. This relates to each citizen as individual rather than as member of a community. Historically, the Romans had the concept of civitas. This means the community of people who enjoyed rights and performed duties and is akin to the concept of citizenship of today. We have hinted earlier that the conception of citizenship links the members of a society with the public authority, the state and the law in a manner where each is treated as a juristic personality and equal. This provides basis for political community in which citizens and public authorities are linked with certain rights and duties. Civil equality stands for equality in which each citizen is provided with equal civil rights and liberties.

Equality in the ‘civil’ sense applies the secular criteria of citizenship to relate individuals with rights. It excludes any other criteria of identifying individuals for the purpose of distribution of rights. Further, civil equality also implies equality of all citizens to have their conscience. This means equality of religious rights such as the right to believe and profess a religion. While equality of right to contract provides basis of economic transactions and economic relations on equal terms, equality to have a conscience results in equality to have religion or not to have a religion. Civil equality in the Indian context may require that a uniform civil code should be formulated for all citizens. However, the multi-religious context and need for respecting the practices of all religions, requires respecting a variety of practices that are civil in nature. For example, one can argue that civil equality does not mean that all members have equality to marry in a particular way or wear clothess in similar way or give divorce in the same manner. The argument for any such parity must go beyond the civil equality argument and invokes bases such as human rights, gender equality, human dignity, etc.

Nevertheless, civil equality is the basis of equality of citizens and a political community, which is based on equality of its members in terms of rights and liberties. It is important for the success of democracy and operation of the principle of political majority. Principle of political majority requires that it should consist of equal citizens and not a permanent or fixed majority based on religious identity or majority based on caste or race. Equal citizens, not their social, religious or any other identity, are basis of political majority. Civil equality is also important in sustaining a nation-state based on secular identity. Citizens are members of a political community irrespective of their social affiliations. Civil equality helps create citizens out of social affiliations. For example, in a court of law or in terms of voting rights, one is not differentiated because of their origin or social affiliations. The basic assumption of civil equality is citizenship.

Legal Equality

Civil equality means equality as citizens. Nevertheless, civil equality is based on legally available rights and liberties. Legal equality is a juristic concept and implies equality before law. Hobbes, Bentham and Austin advocated a concept of legally defined rights and duties of those who are members of a political community. This means that law treats all members of the political community as equal juristic personality. For example, two members of a family when they go to a court of law for a decision on an issue relating to inheritance, the court of law treats them as equal juristic personality or claimants to begin with. This means both are recognized as having equal claim, have equal right to represent and defend and equal right to property. Thus basic assumptions in legal equality are: (i) equality before the law, (ii) rule of law, (iii) each person as juristic personality, i.e., individuals as legal entity not as X, Y, Z.

Equality before the law means law treats everybody as equal and neither discriminates against nor confers special privileges. It is, as the Indian Constitution vide Article 14 provides, equality before the law and equal protection of law. However, this does not mean that reasonable distinction will not be made. Law make exceptions to the general rule of legal equality but that too to make reasonable distinction on behalf of women, infants, minors, mentally and physically impaired, etc. In extraordinary situations, law also admits reasonable restrictions on legal equality and may treat individuals differently. For example, in India, under a particular Act, equality before the law and equal protection of law has not been available as it deals with national security, terrorism, law and order.

Historically, the Romans had the concept of lex, i.e., law, as the basis of defining public affairs and the state. Law was considered as the basis of Roman rule and state power.29 However, it was in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, during the English and the French Revolutions in Europe that the voice for legal equality arose. The emerging capitalist class asserted their claim for legal equality against the aristocratic class and the nobility. Legal equality demanded by the emerging classes was aimed at abolition of special privileges and benefits enjoyed by the aristocracy and the nobility. Particularly, the American and the French Declarations extolled the virtue of equality of men. The American Declaration mentioned that ‘all men are created equal’ and the French Declaration announced that ‘men are born and remain free and equal in rights’. This assertion of equality could be interpreted in two ways: firstly, as a laudable normative assertion that all human beings are equal in their dignity and worth, and secondly, as assertion of the rising class against the already dominant and well-entrenched aristocracy and nobility. In either case, it was an assertion for equality in the formal sense that became the basis for legal equality. Legal equality asserted that no special privilege should exist.

Rousseau in his Social Contract identified legal equality as the main characteristic of civil society. Jeremy Bentham, the Utilitarian philosopher who is also known as the father of modern legislation, advocated legal equality. ‘Each to count as one’ was the principle for both legal equality and utilitarian calculation of the greatest happiness of the greatest number. It does not admit special privilege for some or discrimination against others. Barker in his Principles of Social and Political Theory states that each legal personality is equal to every other in terms of legal capacity. He treats legal equality as main principle of allocation of rights as guaranteed conditions. Rights are to be guaranteed to each and all in the same measure. He points out that legal equality connotes the condition and not the end product. Equality as a principle means equality of opportunity and not equality of results. However, Barker is of the view that legal equality is always conditioned by social and economic criteria. He feels that divergence between legal equality and social and economic equality is inimical to the realization of legal equality. In fact, socio-economic factors had influenced extension of legal equality to the poor, the slaves, and even women. Women have been denied equality under the law regulating suffrage for a long time even in England. In India, we find women have not been provided with the right to inherit property and it is only recently that coparcener rights have been introduced.

Legal equality does not guarantee equality of treatment by the law. Even equal access to law is also arguably in doubt due to monetary implications. It cannot be true that a rich and a poor person have equal access to law. What we mean here is that to defend and represent one's case, one has to employ a lawyer. It is understood that everybody cannot boast of equal access to law if there is no equal access to the persons through which you reach the law. Capacity to employ a lawyer is an important consideration as far as the ‘equal access to law’ principle is concerned. Economic inequality cannot be ignored and equal access to law assumed. Even the provision of a public lawyer or public prosecutor and legal aid does not provide much help to the poor. Further, legal equality by no means guarantees that socially and culturally entrenched discriminations will be over. In fact, Karl Marx in his On the Jewish Question pointed to the limitations of legal and civil equality to ensure absence of racial discriminations.

However, this is not to deny the importance of legal equality. Firstly, legal equality makes the rule of law possible. This means law rules and everybody is subjected to the dictates of the law. This is a significant concept for the dealing of public officials and the state as legal entity with the citizens as legal entities. It makes it possible for a citizen to seek remedy against the unlawful activities of the state or public officials. Rule of law is also considered as an important factor in the development of constitutionalism. Secondly, legal equality abolishes special privileges and discriminations based on caste, birth, religion, race and such other factors. To this extent, it brings equality of persons as legal entity. It provides a secular basis for the state to relate to the members of the society as citizens. Thirdly, concept of legal equality also provides basis for contract and contractual rights and obligations. The hallmark of feudal or ancient social and economic relations was status-based rights and obligations. This means there were hierarchical rights and obligations and not equal rights and obligations. Legal equality provides the basis for contract-based relations. Contractual rights and obligations are useful for the operation of commercial, economic and market transactions, property rights and protection of intellectual rights.

In brief, we can say that legal equality provided a break from the status-based relations of feudalism by replacing it with a contractual relation. It provides a basis for rule of law, abolishes discriminations and special privileges and provides a concept of legal personality to each person. However, legal equality is not sufficient and requires social and economic equality. It is important to note that Tawney, Barker and many others recognize that equality was first demanded in its legal dimension followed by political and economic equality.

Political Equality

When Abraham Lincoln delivered his famous Gettysburg address on 19 November 1863 in the thick of the American civil war, he expressed his anguish and pain, apprehending whether the nation could endure such a long such a civil war. Optimistically, he ended his address saying a few words that have come to be closely identified as the principle of democracy and political equality. He said ‘that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people’, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from earth.’30 The ‘government of the people’, by the people and for the people’, suggests that citizens constitute the government and government exists for them. It implies principle of political equality. However, if Leslie Lipson (The Great Issues of Politics) has to be believed, ‘normally and customarily the many have been governed by the few for the benefit of the few’. Political equality is an ideal to be pursued if a government has to be based on equality of political rights of the citizens and is representative of people's aspirations.

Political equality generally means two things: (i) equality in terms of political relations as citizens having equal political rights irrespective of birth, caste, gender, religion, gender, etc.; and (ii) equal distribution of political power and influence. In the first, we do not seek political equality as father and son, or doctor and patient but as two citizens. This necessarily involves concept of citizens having equal political rights and equal political rights become the basis of political equality. In the second, a democratic government is envisaged. Political equality includes:

- Equality of voting rights—’one person, one vote’ and extension of suffrage to all eligible citizens irrespective of their social, economic, gender and other affiliations—universal suffrage.

- Equality in terms of forming political associations and expressing political views.

- Equal rights to get represented.

- Equality in contesting elections and holding public offices (of course, there can be positive discrimination in favour of underprivileged to compensate for previous deprivations such reservation of seats for women in Panchayati Raj Institutions in India).

- No special privilege to a few to rule, e.g. democratic government.

It is understood that demand for legal equality was followed by demand for political equality or the two emerged simultaneously. R. D. Raphael, for example, has suggested that demand for equality during the French Revolution was also for ‘removal of arbitrary privileges, such as that which confined political equality to the rich and the well-born.’31 R. H. Tawney (Equality) and Ernest Barker (Principles of Social and Political Theory), amongst others, suggest that demand for legal equality preceded political equality. Historically, Greeks and Romans though may not have the idea of citizenship that we understand at present, people were equally participative in political life. Barring, slaves Greeks enjoyed civic freedom for political participation. All Greeks, except slaves, were equal participants in the matters of the city-states. During the Roman period, participation and representation from the three elements of the Roman society—’the monarchical element, the aristocratic element (patricians) and the democratic element (plebeians), were embodied in the Consuls, Senate and the Tribunes’.32 During the medieval period, there was no concept of political equality as feudalism was based on status and privileges. Further, political equality could not be expected when divine rights of kings to rule were invoked.

Development of the concept of political equality in modern times has been influenced by many factors:

- Firstly, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the English, the American and the French Revolutions contributed to the development of the concept of political equality by espousing equality of rights of individuals. In this, the natural rights doctrine also played important role as it talked about equality of rights;

- Secondly, the social contract theory by assuming equality of all to enter into contract, as Locke said, to institute a government as a trust, contained the seed of the concept of political equality. It discredited the divine rights doctrine, which used to invoke hereditary right to rule;

- Thirdly, emergence of democracy as a form of government provided an over all sense of political equality. Alex de Tocqueville, in his book, Democracy in America observed about the consequences of democracy. He says, ‘its (democracy) main tendency was to produce social equality’,33 social equality in terms of abolition of hereditary distinctions of ranks, privileges etc. Political rights and privileges were also based on social privileges and demand for social equality implicitly contained the seed of political equality as well;

- Fourthly, the concept of citizenship provides the basis for political equality. While legal equality means equality of individuals as juristic personality, political equality means equality of individuals as citizens. A citizen is a politically determined individual who possesses political rights. A layman or laywoman may pronounce that he or she is not interested in politics, interpreting politics in terms of pettifogging and skulduggery or alleged manipulation by politicians or corruption. However, for a student of political studies it is intriguing to reconcile how can one be disinterested in politics and be a citizen? Some may say that this is a puritanical view of citizenship and to enjoy political rights one need not be interested in politics. To say the least, the latter view is at best a view of citizenship with political apathy. One cannot be a member of the political society or modern nation-state without being a citizen of that nation-state. By virtue of being a citizen, one enjoys equal political rights. To be a citizen with equal political rights, one should be a politically motivated citizen. To be a politically motivated citizen is not only equal to indulging in politics as we understand, but to even be sensitive to one's voting rights, choosing the leader consciously through whom one is represented in the legislature, being participative in the public issues, etc.

Concept of universal citizenship is a modern democratic concept. However, selective endowment of political affiliation upon inhabitants had been witnessed in empires and sultanates also. In AD 212, Roman Emperor, Caracalla conferred Roman citizenship on all non-slave or free inhabitants of the empire. However, in a few sultanates and kingdoms ruled by Muslim rulers, people belonging to religions other than the religion of the ruler had to pay a compulsory toll tax called Jaziya. Those inhabitants who professed religion other than that of the emperor or the king paid this tax to maintain political affiliation with the state. However, this practice was based on political inequality of inhabitants on the consideration of different religions. Hitler stands out as a rare example who, in 1935, deprived the Jews of German citizenship. In short, universal citizenship as a modern democratic concept is manifestation of political equality.