10

Principle of Justice

Introduction: Equity, Fairness and Justice

In political theory, a great debate revolves around the normative concepts of equality, fairness, justice, common good, general welfare, etc. These are called normative concepts because they generally prescribe ethical or moral standards. If these normative concepts have any meaning as organizing principles of social and political life, then we must understand what they are and how they influence social and political organization, distribution of material resources in the society and policy of the public authority. Justice is derived from the Latin word, jus (also written as ius) or justus meaning law or rights or justitia/justus meaning justness or reasonableness. Justness or reasonableness can be generally understood in terms of either administering public policy or administering law. For example, public policy, which is related to distribution of public employment, can invite principle of just distribution. Secondly, justness or reasonableness can also apply in administering prevalent laws. As such, justice can be treated as a principle or a mechanism or a process that is concerned with fair or just administration of either the prevalent laws or redistribution of societal resources. In this way, justice is related to two different aspects. First, it is concerned with administration of the prevalent laws based on principles of legal equality. Principle of legal equality includes equality before the law, equal protection of law, natural justice, due process or procedure established by law, etc. Second, justice is concerned with the distribution or redistribution of resources such as public employment and offices, economic and other material resources and other opportunities. While the first involves some sort of legal and procedural aspect, the second implies moral and ethical position.

Two important concepts that are linked with the concept of justice are, legal correctness and ethical or moral correctness. Justice, for example, may evoke two opposite reactions: (i) justice means legally correct conduct or public policy; (ii) justice means morally or ethically correct conduct or public policy. In other words, one may argue that justice means what is just according to law and contrarily somebody else may argue that justice means law must be according to what is just. The first notion requires impartiality in conduct while dealing with people in terms of law, legislation and public policy. It also requires that procedurally correct actions should be ensured while executing a law. For example, if a public policy requires that all who are below poverty line would be given reservation in employment in government jobs, it would not be just if those who satisfy this criteria are excluded and those who are above poverty line get the job. This would be possible if impartiality and procedural correctness is not maintained in administering the policy or the act or the law. This is within the realm of impartiality and correctness of conduct. On the other hand, the very fact that only people below poverty line are provided with reservation means there is already an ethical or moral criterion that has gone into determining the justness of this category. Someone may say, why only people below poverty line, why not those who, though above poverty line, are socially and historically suppressed or excluded. The criterion that goes into determining the very scope of those who should be given reservation, for example, falls in the realm of justness. This is based on ethical or moral criterion, which decides how law should be.

Following from this, justice can be described in two ways: procedural justice and substantive justice. Procedural justice is justice as per procedure laid down and this involves impartiality and fair play in conduct or administration of laws and public policy. Substantive justice is justice as per its outcomes and this involves ethical and moral criterion of deciding what is just. Procedural justice ‘relates to how the rules are made and applied’ and substantive justice means ‘whether rules are just or unjust’.1

In the first case, we are concerned with the procedure of making and application of the law, in the second the very content of law is judged from the standpoint of being just or unjust.

The term ‘equity’ normally describes procedural fairness or correct actions or impartiality in treatments. This is related to fairness in the process of administration or execution of a public policy or law. Equity is justice according to law, though influenced by principle of fair play. Justice, on the other hand, requires a substantive, and morally and ethically correct principle for treatment. Reasonableness, fairness and moral correctness should decide the content of law, not vice versa. Law should not determine what is morally or ethically good or bad. Some may argue that what is legal is not always moral or ethical and vice versa. They may cite an example, to prove that what is legal or permitted by the sanction of the State may not be moral also. For example, drinking or prostitution may be legally permitted and could be a source of revenue for the State, but arguably that does not mean they are also morally or ethically correct. On the other hand, some may also argue that law reflects crystallized and consensus-based or agreed upon principle of what is common good or general welfare and there is no need to apply external criteria of judging its justness or reasonableness. Notwithstanding debates on these aspects, it is generally agreed that we should differentiate between procedural and substantive justice. However, we should note that procedural justice is generally argued within the legal and negative liberal perspective, while forceful argument for substantive justice is put forward within the positive liberal, welfare and social democratic perspectives.

Procedural justice emerges when established legal procedure is followed in treating somebody. In this sense, justice becomes a procedural matter and justice appears to have emerged if the application of just procedure is done. For example, justice will suffer if there is denial of pretrial release or bail in cases where substantial risk is not there of absconding; absence of fair trial, which means decisions have been influenced by external considerations; denial of natural justice, which requires that everyone should get a chance to represent in the court of law or denial of legal aid to the needy. The Indian Constitution, under Article 21, provides that, ‘No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.’ Procedure established by law ‘has been judicially construed as meaning a procedure which is reasonable, fair and just.’2 It excludes any arbitrary action on the part of the authority to deprive some one of his/her life and liberty. In the US, due process of law becomes the basis for procedural justice, which requires the process to be reasonable and fair.

Justice has been used in universal or absolute as well relative or contextual meanings. In universal or absolute meaning, justice is treated as virtue or righteousness of which Moses spoke on Mount Sinai as the Ten Commandments, of which Jesus spoke in the Sermon on the Mount, of which Muhammad preached in the Koran, of which Krishna spoke in the Gita, of which Ashoka spoke as Dhamma or Plato meant in his The Republic by justice. Justice is treated as immutable, infallible, universal virtue or truth that must be realized and followed. In a relative sense, justice is treated in terms of social requirements and organizing principle. Justice must be as per social needs. For example, the concept of justice as approved by liberal perspective and that too by the utilitarian school or egalitarian—welfare perspective or libertarian perspective or Marxian or anarchist perspectives will all be different. However, by relative, we do not mean that justice in relative sense is less a normative value. In fact, in all perspectives justice remains a normative concept in the sense that it is a desirable value. Justice, in a way, presents a variety of interpretations such as:

- Justice as virtue, righteousness and absolute truth: Ten Commandments of Moses, Dhamma of Ashoka, etc. Justice in this sense is derived from religious or supernatural sanction. However, its contents are based on the sanctity of human relationships and community life. It is interesting to note that most of the canons of justice derived in such a way are comparably present in all religions. For example, do not harm or hurt your neighbour either materially or emotionally, do not lie and bear false witness, help the needy, do not appropriate other's belongings, etc. Religious and supernatural sanction is invoked to provide validity and relevance to these canons of justice. In a very abstract sense, justice as virtue or righteousness could be universal and absolute. However, in a multi-religious society, it may become a basis of internal conflict if followed as criteria of political organization. This is primarily because these canons can be interpreted differently by different religious affiliations.

- Justice as normative, ethical and moral conception of organizing social and political relations: Plato's conception of justice as following one's virtue (philosophical, courageous and acquisitive nature of individual) or Aristotle's conception of distributive justice as treating equal as equal and unequal as unequal or what Roman Emperor Justinian meant ‘giving each man his due’. Here, justice is not derived from a religious or supernatural sanction but from the very relationship that human beings bear in community or social life. Justice is what each deserves as a member of the community based on one's entitlement. The entitlement is decided on personal ability or capacity. The personal ability or capacity, in turn, is assessed in terms of contribution one makes to social welfare or community well-being or participation in the political life of the community. This assessment is not in terms of mere social needs but a desirable ideal community such as Plato's Republic or Aristotle's Polity.

- Justice as social requirement: Bentham's utilitarian tenets, utility or happiness. Justice is derived from the principle of Utility where greatest happiness of the greatest number is taken as the criteria for judging how legal, material, moral and social resources are to be distributed. Utilitarian perspective requires that both morality and law should produce the same result, i.e., happiness. Bentham gives importance to law and suggests that law is always meant to produce Utility. In this, there is no dichotomy, which we encounter in terms of law as per justice and morality versus justice as per law. Happiness is the overriding social requirement and justice consists in subscribing to this requirement.

- Justice as distributive principle: This refers to the principle of distribution of rights, social, material, welfare and political resources amongst the members of a society. Justice for Barker presents a synthesis of values, liberty, equality and fraternity or cooperation. Rawls's distribution principle is where only that inequality is permitted which leaves everyone better off is a basis of welfare justice. However, Nozick presents a libertarian view of justice and seeks distribution as per entitlement. Social Justice or substantive justice seeks redistribution of material resources and public opportunities in such a way that it results in equality of outcomes. Justice as distributive principle involves just principle in distribution of initial conditions as well as end products. In the Marxian perspective, justice relates to social ownership of means of production and economic equality.

- Justice as what law requires: This means justice consists in following the procedure laid down by law in deciding a particular case. For example, the Indian Constitution bars double jeopardy and requires that no one should be punished twice for the same crime or unlawful/illegal activity. Justice means, a person not being punished twice for the same crime of activity, which is unlawful or illegal. It is justice as per what Indian Constitution says, procedure established by law (fair procedure) or what the US follows, due process of law (a process which is reasonable and fair).3

- Justice as relative concept: Justice means different things to different people. There cannot be a universal criteria of deciding moral or ethical or cultural principle, which could be uniformly applied to judge what is just or unjust. Variety in interpretation of justice emerges due to different conceptions of what is moral, ethical and desirable as different religious and moral frameworks have different meanings. It also varies due to different foci such as on individuals, groups, class, caste or gender. Further, cultural and ethical pluralism impart varying emphasis on cultural and ethical goals, individuals and groups or society should follow. Cultural pluralism recognizes diverse social norms, practices and customs in different socio-cultural groups. Ethical pluralism gives recognition to diversity of ethical goals or ends and moral values pursued by individuals and groups. Due to these variations in emphasis on moral and cultural goals, distinguishing just from unjust becomes a judgmental issue. Justice as such becomes a relative concept4 whereby it means different things to different people. Related to this is the problem of deciding what should be the content of law. If we argue that law should be based on moral and ethical contents, it becomes problematic due to the variety of interpretations of what is morally or ethically desirable. Additionally, even if it were granted that law is based on certain moral principles and ethically approved values of a given society, its impartial execution must be ensured despite different background of the judges?

Let us take three issues, which have a bearing on how a court of law interprets them. In Indian polity, issues related to nationalization and private property, reservation in public offices and Uniform Civil Code, have been matters of intense political and legal debate. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, nationalization of various sectors of the economy including banking, insurance, manufacturing, etc. also implied issue of fundamental rights to private property. It was felt that political initiatives of nationalization might not get favourable support in terms of legal interpretation by the courts and in the name of private property as a fundamental right nationalization cases may not be upheld. Secondly, the court has generally applied various criteria to interpret political initiatives for providing reservations in public employment and offices. It has been pronounced that reservation should be subject to certain conditions, such as administrative efficiency, exclusion of the creamy layer, overall ceiling of 50 per cent of jobs, seats or public offices, etc. Thirdly, court has drawn attention towards need for a Uniform Civil Code in India irrespective of personal religious and cultural rights granted by the Constitution. In all the three issues, aspects relating to social, religious and political background of the judges may be important. There is a need for the judges to interpret issues based on certain ethical and moral or social and national commitments. Interpretation of court of law should not and cannot be based on justice as a relative concept.

This means justice could be related to, what Heywood says, ‘commonly held values in society.’ Heywood refers to Patrick Devlin's book, The Enforcement of Morals (1968) in which Devlin differentiates between consensus laws and non-consensus laws.5 The first means laws, which conform to generally accepted standards of fairness or justice, and the second means those laws, which are regarded as unacceptable or unjust. In the Indian context, for example, there is consensus on provision of reservation in public employment and public offices for the members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. However, the same level of consensus is not visible on the provision of reservation in public employment and public offices for the members of those who have been designated as the ‘Other Backward Classes’. As a result, we have witnessed protests against such initiatives by certain sections of society. However, one can argue that it would always be the case that some or the other sections of society would oppose a given particular law and if we subscribe to the designation of non-consensus law, then most of laws would fall in this category.

This raises a pertinent question relating to relevance of law as a mechanism of social justice or social engineering. Law may be used to enforce a conception of justice that is being opposed by a small but dominant section of the society because it is perceived to be inimical to their interests. It is true that all laws cannot be consensus laws, if they are to be an instrument of social change and social justice. The State, as a welfare state or a social reformer state, would be required to evolve consensus or general acceptance about certain distributive principles. In India, e.g., policy of reservation in public employment and public offices for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, for Other Backward Classes, for women, and even for minorities has been a matter of debate and discussions. Particularly, in the case of reservation for the Other Backward Classes in public employment and women in case of public offices in local bodies, the matter has been controversial and has met with varying degree of opposition. Further, talk of reservation for a religious minority has met with outright rejection. Thus, we find a varying degree of acceptance for a similar mechanism, i.e., reservation, for different sections of society. This can be related to a relative concept of justice that needs to be applied differently to different groups in society.

Diverse Perspectives on Justice

Justice has been a widely debated throughout political history and has been understood differently. We may survey briefly some of the representative interpretations given by great political thinkers in different ages of political history.

Justice During the Greek Period: As a Virtue of the Social Order

Plato—Concept of justice as moral conduct by individuals and social classes

The principle of justice is the central argument in Greek political philosopher Plato's Republic. According to Will Durant, Plato seeks ethical solution of an ethical problem. The ethical problem is what ‘is the crux of the theory of moral conduct. What is justice? Shall we seek righteousness, or shall we seek power?’6 Plato treats justice as both a principle of individual right conduct and an ideal social order. The first he finds in the three faculties of the individual, the second in the three social classes. He actually seeks the basis of a just social order or the state in the very nature of human beings. This means, if each individual does what one is best suited for there will be specialization as well as non-interference in each other's work, i.e., harmony. Richard Lewis Nettleship in his Lectures on the Republic of Plato says, ‘Justice in Plato's sense is the power of individual concentration on duty’ which means ‘each man should devote himself to that one function in the state for which he was by nature best suited.’7 As such, justice is a sense of duty in the individual of doing what one is best capable of. Then, how would one know what is the best work for oneself? Plato correlates suitability with individual dominant faculty, which he presents as ‘trilogy of soul’ or what Barker calls ‘doctrine of the triplicity of the soul’.8

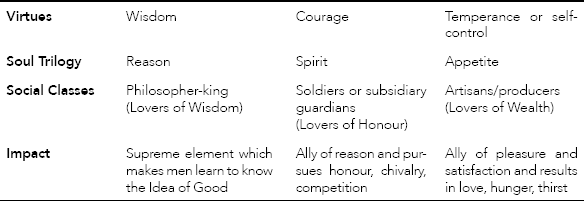

Plato correlates the cardinal virtues to which the Greeks gave importance, i.e., Wisdom, Courage, Temperance or Self-control, and justice with the different faculties that an individual soul possesses. He assigns three different faculties—Reason, Spirit and Appetite that the soul possesses. This soul trilogy is to show that there are three inherent and innate qualities of the soul in each human being. However, different human beings have different faculties as dominant—in some, reason will be predominant, in some other, spirit and yet some others will have appetite or desire as their dominant faculty. He relates virtue of wisdom with faculty of reason; virtue of courage with faculty of spirit and virtue of temperance or self-control with faculty of appetite or desire. Corresponding to the three virtues and three faculties of the soul, Plato also suggests three classes such as philosopher-kings or guardians, soldiers or subsidiary/auxiliary guardians and artisans/producers (see Table 10.1).

After relating virtues with faculties of soul and the three classes in the social order, we can quote Plato saying that ‘justice is the having and doing what is one's own.’9 This means, justice is performing as per dominant faculty and receiving what one produces. This is possible only when, what Will Durant says, ‘there is effective coordination and harmonious functioning of the elements in a man, each in its fit place and each making its cooperative contribution to behaviour.’ Each faculty in individual does its own work and produces just condition. It requires understanding of one's faculties and using each faculty as best suited. This means the first step is to know which the dominant faculty is and this requires reason to tell that and direct the dominant faculty to realize its position. This results in specialization and emergence of classes that can be categorized as per the faculties.

In terms of social classes, society is ideal when each class does what it is best suited to—having reason as superior faculty rules, having courage as faculty guards and being an ally of reason and having nutritive or appetitive faculty and engaging in production and artisanship. Justice is what each class does as per dominant faculty. This results in specialization, excellence and efficiency. For Plato, a state is efficient and excellent because it is just. Plato argued that those having wisdom and reason must rule as reason establishes coordination amongst the other faculties and has the capacity to balance all the faculties. If Spirit or Appetite rules, selfish interest prevails either in search for honour or pleasure, but when Wisdom rules, it seeks unlimited Good and welfare of all. Plato identifies rule of Spirit with military character and of Appetite with economic character. It is only the rule of the philosophers that would institute an ideal state.

Plato's justice is distributive justice and seeks to provide moral and ideal criteria for individual conduct and ideal social order. This social order is harmonious, just, specialized and efficient. Justice becomes what Nettleship says, ‘one does his own business.’ However, Plato's categorization of soul is not based on any rational criteria and is often related with the ‘myth of noble lie’. This means it seeks origin from the myth that philosopher kings are made of gold, soldiers of silver and artisans/producers of bronze. It is interesting to note that a similar criterion is invoked to relate origin of castes in India—head/mouth (Brahman), shoulder (Kshatriya), thigh (Vaishya) and feet (Shudra). However, the difference between the two schemes appears to be the flexibility, which Plato gives in the form of circulation of individuals from one class to another with change of faculty. Nevertheless, Plato could not escape the criticism of R. H. S. Crossman (Plato Today) and Karl Popper (The Open Society and Its Enemies). Crossman and Popper find his theory opposed to liberal ideas and Popper treats him as enemy of the open society and his idea as ‘unmitigated authoritarianism’. C. E. M. Joad is also critical and finds striking similarities between his idea and ‘fascist totalitarianism’.

Aristotle—Concept of distributive justice

Greek political philosopher, Aristotle seeks to construct an ideal polity with a balanced class composition, which means a predominant middle class, neither extreme of poverty nor extreme of aristocracy. However, the problem of relative claims of classes to power in polity needs to be resolved and criteria to be found out for justifying relative claims. Primarily, it has to be a criteria of distribution of public offices and privileges in the polity. The aim is to find out the principle of distributive justice. Distributive justice for Aristotle is principle, which helps in distribution of offices, wealth, rewards and dues to social classes as per their contribution to the state. This means distribution is related with contribution, which in turn is based on merit.

Aristotle's famous statement that ‘injustice arises when equals are treated unequally and also when unequals are treated equally’ proves that he advocates ‘proportionate equality’ based on equal shares according to merit. Primarily, it is a principle of equality of treatment based on equal merit, which means distribution of rewards, wealth, offices, etc. in proportion to respective contributions. Secondly, difference in treatment should be proportional to the degrees to which individuals and classes differ in relevant respects. Thirdly, justice means fair and reasonable inequality of treatment.

However, if rewards are to be in proportion to contributions, it is necessary to determine the criteria for deciding contributions of each class to the polity. If there are three classes namely, Aristocrats, Oligarchs and Democrats, their interpretation of justice will differ as per the virtue or goal they pursue. The three classes will obviously interpret justice differently. There can be differences as to what constitutes merit, civil excellence and equality. Is everyone to count as one or wealth, education and social position to count more than one in deciding equality? For example, aristocrats may claim that high birth and education constitute high virtue and makes highest contribution to the state and hence offices and powers should go to them. Oligarchs may claim that wealth makes the highest contribution to the State and should have the largest share of offices and rewards. Democrats who may consider free birth as the highest desirable virtue for social equality would like to set social equality as the principle of distributive justice. This means there are conflicting claims to power and offices. Now, Aristotle is required to balance between high virtue of birth and education, wealth and free birth.

Two aspects of Aristotle's thought become significant here. Firstly, Aristotle accepts the moral consequences of property such as liberality, charity, individuality, etc. Secondly, he accepts that collective wisdom of the majority is improtant as polity is based on a predominant middle class. If these two aspects of his thought are taken into account, he could not deny either wealth or free birth a share in distributive justice. As a result, though Aristotle is inclined to give virtue of high birth and education a higher share in the state, he concedes a relative share to oligarchs and democrats.

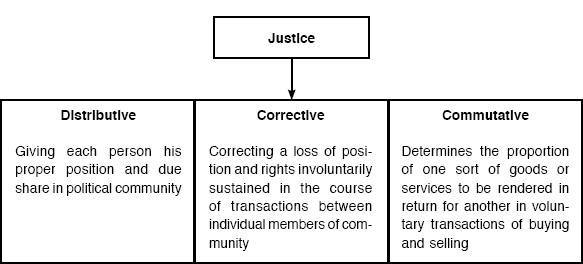

According to Barker (Principles of Social and Political Theory), Aristotle identifies three types of justice, namely: (i) distributive justice based on proportional equality, (ii) Corrective justice based remedy for wrong done, and (iii) Commutative justice based on justice in exchange of goods and services (see Fig. 10.1).

While distributive justice applies in the political arena, corrective justice applies in civil relations and application of civil and criminal laws, and commutative justice applies in the realm of economic transactions. As far as distributive justice is concerned, Aristotle seeks to find a practical solution to the political problem of how to distribute offices and positions. Compared with Plato, Aristotle is seeking a principle that can be applied in a practical state while Plato seeks principles to be applied in an ideal state.

Concept of Justice During Roman Period

Justice according to the natural law and right reason

The Greek thinkers were oriented towards justice as a principle relevant to the social order. Plato argued for harmony of classes in accordance with station in life and Aristotle struggled for distributive justice. Their conception of justice was for a social order in the polis, the city-state. Subsequently, the Stoics led by Zeno held nature as a rational-whole and universal Law of Nature as the basis of natural equality and justice common to all men. Sabine opines that ‘The fundamental teaching of the Stoics was a religious conviction of the oneness and perfection of nature or a true moral order.’10 He further says that the Stoics believed that the right reason was the law of nature and the standard of what is just and right everywhere. Reason becomes the law for all men, which is unchangeable and binding on all men, ruler or subjects. We can say that the contribution of stoics lies in two aspects: (i) shift to a concept of a universal state instead of the Greek focus on polis or the city-state, and (ii) law of nature as the basis of justice instead of the morality of the individual and social classes. The Stoics’ contribution of law of nature as a moral system to which human laws should conform lays down universal standard of conduct.

The emphasis on natural law became an important thread picked up by the Roman lawyers and statesmen. Cicero spoke of right reason as ‘true law’, being eternal and unchangeable, applicable to all men. The code of Roman law has come to occupy an important place in evolution of law. During this period, law came to be differentiated into three categories — jus naturale (law of nature), jus gentium (law of nations) and jus civile (civil law, customary law of particular state). While natural law was right reason and unchangeable, law of nations was what was being practised in relations with citizens and non-citizens. For example, while natural law implies everyone is free and equal, slavery was being practised and came under law of nations. Law of nature influenced the works of Cicero and the Roman lawyers such as Gaius, Ulpian, and others. Under this tradition, justice was treated as a fixed and abiding disposition to give to every man his right and the lawyer became a ‘priest of justice.11 Law as such becomes ‘the science of the just and the unjust’.

Marcus Tullius Cicero—Concept of Justice founded on natural law

In Cicero, we find a great Roman statesman and an eminent political thinker whose De Republica (the Republic or the Commonwealth, the ideal state) combines the ideals of Plato's Republic and Aristotle's Politics and is comparable to both. His other book, De Legibus (The Laws) provided the type of legal system that his ideal state would require. Cicero wrote when the republican constitution of Rome was under threat and tension between monarchical (Caesar and consul) and aristocratic (senate) elements were on high. His times (106–43 BC) coincided with that of Caius Julius Caesar (101–44 BC). We can imagine Cicero speaking in the senate when Pompey, having provoked Julius Caesar who was camping in Gaul to cross the Rubicon with his army, was seeking the support of the Senate. Cicero must have been witness to the decline of the republican Rome, dictatorial rise of Caius Julius Caesar and Cleopatra being established as queen of Egypt under the Roman suzerainty.

Cicero's ideal of justice is contained in his idea of the commonwealth, i.e., the political community and natural law. He treats the commonwealth as ‘people's affair’, i.e., affair of the ‘whole community of citizens’ and not of king or aristocracy or of democratic leadership. Commonwealth, to be a people's affair, is ‘coming together of a considerable number of men who are united by a common agreement about law and rights and by the desire to participate in mutual advantage.’12 Agreement about law and rights implies justice as law involves natural law and natural law is founded on justice. While for Plato, a just state could be one which is based on rule of philosophy, for Cicero it is a just state when it is capable of preserving the commonwealth as a ‘people's affair’. Like Plato's philosopher king, Cicero would like his statesman to know the nature and principle of justice. Cicero's statesman seeks justice based on natural law, which is rule of moral reason and establishes unchangeable principles of justice. Cicero forcefully argued that a true commonwealth must realize justice.

Concept of Justice in the Medieval Period

Justice as triumph of theocratic principle

St. Augustine—Conception of justice as Christian ideal: Travelling through various political upheavals but now not witnessed by Cicero or Seneca or such a statesman, Roman Empire in its monarchical form also had closed and gone by the fith century AD. With the decline of the Roman Empire, there came the pagan charge that adoption of Christianity was responsible for the decline of the Roman power. In fact, it was also charged that Christianity was like the owl of Minerva, which sat on the carcass of the Roman Empire. In the early fourth century, Goths (Teutonic people of Swedish and German origin) had started settling in and encroaching upon the Roman Empire. In 410 AD, a section of Goths led by Alaric sacked and devastated the city of Rome. If we look at two aspects, namely Cicero's forceful argument that a true commonwealth (and he was talking about the pre-Christian Rome) must realize justice and the pagan claim against Christianity as having destroyed political power of Rome, we would be able to give a perspective to the thought of St. Augustine on justice.

St. Augustine took exception to Cicero's claim and strongly doubted that a pre-Christian empire could realize justice. This is because he held that a true commonwealth must be Christian. A just state for Augustine is one in which belief in the true religion is given primacy. Secondly, Augustine was to defend Christianity against the pagan charge of it being the cause of decline of the Roman political power. In this context, St. Augustine wrote The City of God (De Civitate Dei) to respond both to Cicero and to the pagan apologists. He stated that man's nature is two-fold—spirit and body or the realm of worldly interests and the realm of other worldly interests. Corresponding to these are earthly city and the City of God. While the earthly city is founded on ‘the earthly, possessive and appetitive impulses of lower human nature’, the City of God is ‘founded on hope of heavenly peace and spiritual salvation’. Only the City of God, a spiritual kingdom, could be permanent. By implication then, fall of Roman Empire could not, and should not, be linked to Christianity, as all earthly kingdoms must pass away. Further, it establishes the supremacy of the idea of the City of God and seeks that ‘the state must be a Christian state serving a community which is one by virtue of a common Christian faith.’13 No state, for Augustine is just unless it is also Christian. Pre-Christian state could not claim, as Cicero wanted, to seek justice.

Unlike Aristotle, who celebrated politics as prime human activity and sought distributive justice or Cicero who sought justice in terms of state as people's affair and natural law, St. Augustine linked authority with God and justice with Christian belief. Political activity pertaining to the realm of earthly affairs was not to find much favour from Augustine. We may say that St. Augustine's conception of justice is related to the heavenly state and City of God. This means, it is necessarily covered under theocratic theory of the state. Augustine supremely believes that justice cannot exist on this earth and even if it exists, would be imperfect. He says, ‘without justice, what are kingdoms but great robberies.’14 Thus, justice, which Plato, Aristotle or Cicero talked about were relative and imperfect justice because justice could be realized only in a Christian state. Augustine's solution is that the state must be the temporal arm of the church serving the authority of God. Justice in such a state would be conformity to order and respect for duties and obligations that the City of God requires.

St. Thomas Aquinas—Conception of Justice as rule of the higher for public good and salvation: A great saint of the thirteenth century belonging to the Mendicant Orders, known as the Aristotle of Europe, was St. Thomas Aquinas who sought close synthesis of faith and reason. He, as Nelson says, ‘integrated Aristotle's philosophy into the corpus of Christian faith.’ Aquinas's ideas on law and justice are contained in his Summa Theologica. Another book, On Kingship, contains his political theory and closely follows Aristotle's Politics. Aquinas's idea of justice could be better understood if we look at two aspects that are related: (i) relationship between the lower and the higher, and (ii) State as a moral community. St. Thomas Aquinas holds that nature is permeated with hierarchy in which the higher rules over the lower as God being supreme rules over the world and soul, being higher, rules over the body. As such, there should be a rule by those who are higher and a rule for public good. Secondly, as Sabine says, Aquinas perceives society as a ‘system of ends and purposes’ or as Nelson says, ‘state as a moral community’.

If we combine the two aspects, i.e., doctrine of hierarchy and the moral end and purposes, we can say that the state ‘has its end the moral good of its members … hence the should be based on justice, that the best should rule for the public good under the constraint of law.’15 If society or state is a system of ends and purposes or mutual exchange of services for the sake of good or moral life, it requires that all contribute as per callings. Nevertheless, what is primarily required is that those who are higher or the ruling part should direct the lower and the lower serves the higher. Justice, for Aquinas, is seeking common or public good through this arrangement. Further, this rule of the higher is to be exercised in accordance with law.

Aquinas sounds like Aristotle in seeking rule of law and sake of a good life in the State. Since, everyone has to contribute as per calling and the doctrine of hierarchy, everyone has ‘station, duties and rights through which one contributes to the perfection of the whole’. As St. Thomas Aquinas seeks perfection in religious terms, pubic good, perfection of the whole or moral life is to be interpreted in terms of salvation of the soul. In short, for Aquinas, justice becomes rule of those who are best for seeking a moral life that ultimately helps in salvation of the soul.

Utilitarian Perspective

Justice as the greatest net balance of satisfaction or happiness

Jeremy Bentham—Happiness as Justice: Epicureans, during the Greek periods, had denied any moral and ideal content to justice that Plato advocated and were of the view that the state was not founded on something like justice of which Plato spoke. For them, justice was nothing in itself but ‘a kind of compact not to harm or be harmed.’16 For Epicureans, it was pleasure, and not justice, that was the central pursuit in the state. In the ninteenth century again, Bentham took up utility as an organizing criteria in the State. The principle of happiness, i.e., the greatest happiness of the greatest number, based on each counted as one, provides the basis of justice in Utilitarian perspective.

Traditionally, justice as a normative concept has an implied moral aspect. Bentham, however, would not accept role of morality in defining justice. Regarding relationship between morals and legislation he says, ‘Legislation and morals have the same centre but not the same circumference.’17 Utilitarian perspective requires that both morality and law should produce happiness. To this extent, they have the same centre, i.e., production of happiness. However, while law is command of a supreme authority in a sovereign state, morality concerns with what Mill would say, self-regarding actions and is ‘beyond the province of law’. Thus, law and morality have different circumferences. If this is the case, morality cannot be the basis of justice for Bentham. In any case, utility or happiness, not justice, is the end that Bentham's state seeks. Justice lies in treating each as one in calculating the greatest happiness of the greatest number. The Utilitarian perspective assumes that justice is the greatest net balance of satisfaction. We will discuss below Rawls's contract-based conception of justice as an alternative to the Utilitarian conception of justice. Rawls, in his book, A Theory of Justice (1971) criticized the Utilitarian concept of justice and set out a contractarian concept of justice.

Legalist Perspective

Justice as creation of the sovereign

Thomas Hobbes, Jeremy Bentham and John Austin supported the legal concept of sovereignty. They argued for the supremacy of law emanating from the sovereign and held that the law was the sole source of rights, liberties and justice. As such, law becomes an instrument of justice. Hobbes's social contract set up a sovereign who must treat all the individuals equally in matters of rights. The idea of contract gives the idea of equal consent and hence sovereign is required to give equal treatment. Hobbes defines ‘justice as equality in treatment and equality in rights.’18 In such rights and considerations as property, levying taxes, contracting with one another, Hobbes requires the sovereign to treat each individual equally. For Hobbes, Leviathan or the sovereign is, what Wayper calls ‘creator of right and justice. His edicts, or laws, therefore, can never be unjust or immoral.’19

Bentham argued that law only can become basis for utilitarian principle and morality cannot become a basis of either of utility or by implication of justice. Austin, a famous analytical jurist of 19th century, also advocated law as source of justice. Society is not supposed to look for justice beyond the juridical order that is the state. State under the legal sovereign becomes the source of positive justice because it is based on positive law. Positive justice does not recognize the argument of moral content of justice. Bentham did not accept morals as the basis of justice because enforcement may not ‘increase net balance of happiness or decrease net balance of pain.’ For example, drunkenness if punished may not contribute to this. Bentham also criticized conception of natural law as a mere phrase and did not accept it as the basis of either rights or justice. Positive conception of justice is based on law and not on either moral content or natural law.

Harold Joseph Laski is critical of Austin's legalist concept. He suggests that Austin by insisting too much on juridical elements excluded ethical and sociological consideration. Laski says ‘Law was completely separated from justice on the ground that … it introduces non-juristic postulates.’20 Laski finds law ‘divorced from justice’ in the perspective of positive justice.

Concept of legal justice, however, plays a significant role in the liberal order. Justice here is primarily concerned with how penalties are to be decided for violation of the existing laws, how compensations to be allocated for damages and injury in interpersonal or economic relations, etc. Justice is to enforce law to penalize the wrong doer (legal wrongs) or compensate the injured. Secondly, justice also requires that the procedure followed should be impartial. Impartiality in the application of law ensures that result of application of law is just. Equality before the law and equal treatment by the law is the basis of justice. This is the statement of formal (legal) justice. However, we may recall what we said with respect to the principle of equality that like legal equality, legal justice would require a socio-economic basis for its realization.

Marxian Perspective

Justice as end of exploitation

In the eighteenth century, demand for justice on economic basis became an important thread in socialist thought in Europe. In fact, economic and social equality and justice became an important demand. The most scientific and vocal argument came from the Marxian school led by Marx and Engels. This is known as Marxian or socialist theory of justice. In Marxian perspective, treatment of justice is not separated from the overall analysis of class relations, private property and private means of production. It does not accept legal justice, which is the mainstay of the liberal school. Marxian or socialist theory of justice talks about distributive principle on economic basis and rejects the concept of legal justice.

Rejection of legal justice as class concept: The Marxian school treats legal system (and also educational, political, cultural) as part of the superstructure, which is determined by the infrastructure or the economic relations. The economic relations that pertain to infrastructure, determine law, politics, education and everything that pertains to the superstructure. In class analysis, law is considered as a reflection of the economic interests of the dominant class. The Marxian perspective forcefully rejects the idea of legal justice, as justice requires resolving the primary contradiction that exists at the economic level. This is because legal justice cannot provide the basis of real justice unless economic relations based on class dominance is eliminated. The focus of Marxian analysis is on economic relationship reflected in the private means of production and private property. It finds private property and private means of production inimical to economic justice. Marx and other Marxian writers advocate justice on economic basis. Barker in his Principles of Social and Political Theory illustrating the emphasis on economic justice given by Marx and others such as Proudhon and Bakunin, suggest that Marx identified justice with communism, Proudhon with ‘mutualism’ and Bakunin with anarchism.

Class analysis does not recognize any possibility of justice in a society where private property exists. Justice in its legal form would always be employed to protect the interest of private property. The main purpose of the state and what Engels calls, its ‘public force’ (armed men, prisons and other repressive institutions), is to ‘maintain law and order’. And Burns adds, ‘but in maintaining law and order it is maintaining the existing system.’21 Legal system is only one of the organs of the state that is meant to reinforce the existing conditions so that the existence of private property is justified. In a society with private property and private means of production, one can argue, the legal system is largely oriented to enforce and secure the terms and conditions of contract that is required for running the capitalist system. This highlights the irrelevance of the legal system and the concept of legal justice as a fair and impartial procedure in a class divided society. It outright rejects the idea that the legal system is fair, impartial and reasonable and could be the basis of even procedural justice. Marxian perspective argues for substantive justice and that could be possible only where the social means of production prevails, i.e., the socialist society.

Impossibility of economic justice and redistribution of surplus value in the capitalist system:

Marxian analysis rejects any possibility of legal justice under the capitalist system. Moreover, in such a system it seriously doubts any idea of economic justice. This is because economic justice requires a substantive concept of justice, which is nothing but the principle of justice in a classless society.

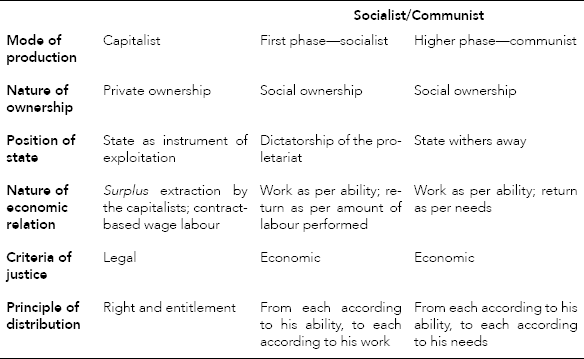

In Marxian analysis, three distinct aspects of distribution can be identified. In the capitalist system, economic relations are based on class relations, private property and surplus value. Roughly, surplus value is related to the following aspects: (i) worth of a commodity produced (i.e., price it is sold in the market), (ii) amount of ‘socially useful labour’ put into it by the workers (Marx showed that worth of the commodity is actually was the value of labour put into it as labour only creates value), and (iii) the amount received by the worker as wages. Marx in his Capital explained that wages paid to workers for producing a commodity is less than the socially useful labour put into it. This means that the worth of the commodity is more than what is paid to workers. Marx considered that labour is the only productive element that creates value and he rejected the argument that the worth of commodity depends on market situation (i.e., demand and supply). If labour is the only productive element, the difference between the wages paid and the worth of the commodity constitutes the surplus value. Since, worker does not get product of labour, the capitalists appropriate it. As such, it becomes an instrument of exploitation of workers, the proletariats by the owners of means of production, the capitalists. In this situation when the instrument of exploitation is inbuilt in the economic relations of classes, can there be possibility of economic redistribution or economic justice? This is the first aspect of economic distribution, which is exploitative. Marx concluded that there could not be economic justice when surplus value was a means of exploitation in the capitalist society. Marxian perspective seeks to remove this undesirable condition. This is possible by abolition of classes through proletarian revolution, which will lead to establishment of dictatorship of the proletariat. During the phase of dictatorship of the proletariat, complete equality is not possible, as it would still be society with class differences remaining. Dictatorship of the proletariat is a class rule but this time the rule of the majority. This is the first phase of communist society.

Economic justice in the first phase of Communist Society: A second principle or aspect of economic distribution appears here. This is ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his work’. It is a revision in the principle of equality, ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’22 which would ultimately prevail in the ‘higher phase of communist society’. This revision is necessitated due to the incomplete nature of transition to the communist society and existence of the state, which has still to ‘wither away’. Lets us briefly see the background in which Marx advocated two different principles of distribution.

Before Marx, some of the Utopian socialists, such as Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825), advocated distribution as per the principle of ‘work’. This was meant to counter unearned income from landed property.23 Unearned income means income that comes from rent on land. Ferdinand Lassalle (1825–64), born to German Jewish parents, whom Lenin calls a ‘petty-bourgeois socialist’, was another thinker who advocated radical ideas on wages and the principle of ‘equitable distribution of product of labour’. The latter means ‘the equal right of all to an equal product of labour.’24 Lassalle advocated criteria of distribution based on work. Lenin, citing Marx's explanation, in the Critique of the Gotha Programme maintains that the equal right criteria in this phase automatically amounts to inequality. Everyone being different in capacity if given equal share for equal performance, would mean that those with more capacity would get more than those having less capacity. According to Lenin ‘the first phase of communism, therefore, cannot yet provide justice and equality: difference, and unjust differences, in wealth will still persist, but exploitation of man by man will have become impossible because it will be impossible to seize the means of production …’25 In this phase, criteria of distribution is ‘amount of labour performed’ and not ‘needs’.

Justice in the higher phase of Communist Society: in the higher phase of communist society, social ownership of means of production would be complete and the state as a bourgeois institution would wither away. The socialist theory of justice based on economic distribution as per needs would prevail. Marx gave expression to the socialist theory of justice in his book, Critique of the Gotha Programme. In this, he proposed that the formula of justice in a communist would be ‘from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’. ‘Need’ here does not refer to wants or preferences or desires, rather it should be understood in terms of ‘necessity’. Necessity or needs, to agree with Heywood, ‘are often regarded as “basic” to human beings …’26 Marxian thought accepts ‘needs’ of each individual as the distributive principle. Criteria such as rights, entitlements, merits or deserts, etc., as the basis of distribution of material benefits and resources are rejected in Marxian framework as bourgeois principle. It suggests that classless society and social ownership of means of production would be the final stage of historical evolution. The principle of justice in a classless society can only be based on needs. Before Marx, François Babeuf and Louis Blanqui in the first half of the nineteenth century had advocated the principle of distribution as per ‘needs’. Table 10.2 outlines the Marxian or socialist theory of economic justice.

Marx propounded socialist and communist principles of distributive justice on the economic basis. Principle of distribution in a capitalist society is considered exploitative as it is based on extraction of surplus value. It helps the economically dominant class, which is the capitalist class to accumulate profit through surplus extracted from the labour. In the first phase of the communist society, i.e., the socialist phase, which will come after the revolution, distribution is proposed based on performance of labour, i.e., work. In the final phase, which is the fully realized communist society, distribution is based on needs. Liberal tradition generally invokes the criteria of right, merit or entitlement for distribution. The criteria of needs proposed by the Marxian framework compared with that of the liberal tradition (right or merit), appears more relevant as a basis of a welfare or just society. It is closer to egalitarian principle and relates meaningfully with the concept of substantive justice and justice based on results or outcomes. Fulfilment of needs of human beings seems a reasonable criterion of distribution of material resources.

In the wake of abject poverty and malnutrition in most parts of the world, satisfaction of basic needs of human beings is the primary requirement. These basic needs may include basic medical and health care, education, housing, drinking water, sustainable employment and remuneration. The UN Millennium Agenda does provide a statement of such a vision. If the vow of the international community is to secure distribution of the material resources in such a manner, which at least satisfies the basic needs of the people, then one can ask—where does the Marxian vision falter? We can have ‘hierarchy’ or pyramids or even a mountain of needs, but access to basic human requirements should be priority.

Justice as Synthesis of Political Values

Liberty, Equality and Fraternity

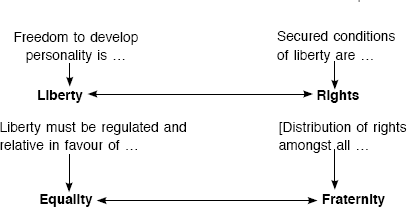

Ernest Barker in his book, Principles of Social and Political Theory has discussed the relationship ‘between liberty, equality and fraternity or cooperation’. He treats these values as important and states that they are ‘recognised by organized system of human relations’ though they are present in at different times and different systems in different degrees. He further suggests that there is a need for ‘constant process of adjustment and readjustment between the overriding claims of different values’. For example, the claim of equality has to be adjusted with liberty and vice-versa (i.e., regulated and relative liberty) and claims of both have to be adjusted to fraternity or cooperation. Liberty means freedom of individual to exercise one's own capacity for development of personality. Rights are secured conditions for greatest possible development of these capacities. Fraternity is the principle of distribution of rights amongst all for common enjoyment. It implies cooperation or solidarity in sharing common means and enjoyment. We can depict Barker's description as seen in Figure 10.2.

If this is the relationship between liberty, equality and fraternity, then how does principle of justice fit in here? Barker states that justice traces its roots from ‘jus’ or ‘justus’ (both Latin) and contains the idea of ‘fitting or joining’. Fitting or joining implies bond or tie between man and man. However, Barker is of the view that this can be also applied between values and values. The fitting or joining of values—liberty, equality and fraternity, is synthesis of values. But how is this synthesis secured, or which principle helps us secure this synthesis where liberty is regulated in favour of equality and becomes relative to liberty of each, and fraternity and equality are adjusted to liberty? The function must require a principle or value that secures this synthesis. Barker suggests that function of justice is synthesis of liberty, equality and fraternity. Justice does joining or fitting between different values and adjusts and reconciles them with each other. Justice as such is a reconciler and synthesizer of political values—liberty, equality and fraternity. In other words, justice is ‘the union and adjusted whole of all political values which are staking claim for recognition.’ Justice, according to Barker, reconciles and regulates the general distribution of rights. It helps give each person his/her share of rights and adjust person to person. Justice is a balancer, adjuster, reconciler and synthesizer of values. It goes beyond liberty, equality and fraternity and balances each of them.

Barker's analysis of the relationship between liberty, equality and justice provides a case for reconciling claims of different political values so that equal conditions for the development of personality of all could be secured. Justice becomes a principle or value that helps adjust and reconcile the claim of liberty (as in liberal view) and equality both legal (in liberal view) and economic (socialist and positive liberal view). Examples of the three values—liberty, equality and fraternity—invoked together are found in the thought of Stoics and the French Declaration. Stoics led by Zeno, about whom we have briefly discussed above, argued in favour of natural law and universal order based on right reason and rational order. Concluding from the rational order they believed that men are rational in nature and as such they should be regarded ‘free and self-governing’ (liberty); being all rational in nature should be regarded as equal in status (equality); and men united with each other by a common factor of reason are linked together in solidarity (fraternity). Barker feels that Stoics reconciled the three principles. We also find that the three principles have been invoked in the French Declaration and in the Preamble of the Indian Constitution along with justice.

Historically, the idea of liberty and legal equality emerged together during the eighteenth century. However, liberalism was not ready to adjust liberty with demand of social and economic equality raised subsequently. Positive liberalism of Mill, Green Tawney, Hobhouse and others, and socialist thought, particularly the Marxian perspective argued that social and economic equality must be realized for justice to be meaningful. The concept of justice and its relationship with equality provides a basis of distributive justice. Aristotle was the earliest thinker to relate justice with treatment of equal as equal and unequal as unequal in terms of distribution of public offices, wealth and privileges in Greek city-state. However, he justified the slavery even though he advocated distributive justice. Bentham's doctrine of one to count as one in determining utility provides the basis for equal treatment. Argument of the analytical school for legal equality becomes the basis for legal justice. Principle of distributive justice has been discussed and advocated by Rawls in egalitarian perspective and by Nozick in libertarian perspective. In India, B. R. Ambedkar has forcefully put forward the need for social equality as the basis of justice. We will discuss the ideas of Ambedkar, Rawls and Nozick below. If justice is related to equality, which it is, then it should seek equality in all in its dimensions—legal, social, political and economic. Though in Europe, legal and political equality was initially achieved it was confined to men only. While social and economic equality still needs to be realized, even legal and political equality for women are lacking in many countries. If justice is synthesis between political values, it must truly reconcile not only liberty and equality, but also their various dimensions.

Ambedkar's Social Justice Perspective

Justice as End of Caste Exploitation

Dr Bhim Rao Ambedkar, a great political and social thinker, lawyer and constitutionalist, is famous as the man who drafted the Indian Constitution. He was the first Union Law Minister after independence. However, behind this great man lies the agony, resentment and anger of those who have been victims of the historical injustice. Ambedkar was born in a Mahar family in Maharashtra, which as per the traditional Indian caste system was considered ‘untouchable’. An ‘untouchable’ caste is traditionally placed at the bottom of the caste hierarchy and is subject to distance and pollution rules of social interaction. This means members of the higher born castes maintain distance from the members of the ‘untouchable’ castes in terms of physical, social, and cultural interaction. Elsewhere in this book, we have noted that untouchability represents a novel innovation of human mind in the history of inequality. It treats even casting of shadow or touch of one human being to another as polluting, leave alone any meaningful social interaction. Untouchability has been a practice of not only social inequality but also of social exclusion. It has not only been a clinical method of excluding a section of human beings from material and economic benefit but has been morally indignifying. Ambedkar, having been born and lived in one of such caste, was aware of the implications of such a social structure for the rights, equality and dignity of the members of these castes. It was logical that he epitomized the agony, resentment and anger of all those who suffered. Dr Ambedkar wrote several books including the famous Annihilation of Caste, Who were the Shudras? The Untouchables, etc.

Dr Ambedkar was critical of the caste inequalities and fought for social justice. What he sought as social justice primarily was abolition of untouchability. The practice of untouchability excluded ‘untouchables’ from social intercourse with other castes, temple entry and access to public places and public facilities such as common drinking water, etc. He was of the opinion that Chaturvarna, i.e., the social structure based on four castes, resulted in inequality and system of untouchability. His analysis of the caste system contained in the books mentioned above, suggests that the practice of untouchability presents a unique form of inequality in society. He firmly concluded that it was not only indignifying but inimical to ‘the mental and moral progress of the untouchables.’27 The logical step forward for Dr Ambedkar was to pursue the goal of social justice. Social justice aimed at abolition of the historical distortion in the form of untouchability and securing equal civil rights, protection of law and equality before the law. As a lawyer and constitutionalist, Dr Ambedkar was sure that legal rights and equality through the Constitution would be the basis of social justice.

Social justice is explained as principle of distributive justice in society which deals with ‘morally defensible distribution of benefits or rewards in society …’28 For Dr Ambedkar, the aim of social justice is to rectify social injustice and restructure the social order based on principle of equality. He was instrumental in making constitutional provision for abolition of untouchability under Article 17 of the Indian Constitution. Equality before the law and equal protection of law provided under Article 14 is statement of legal equality of all irrespective the caste system. While this secured social and legal equality, equality in opportunity required reverse discrimination in favour of the section of society discriminated historically. To compensate for the historical and social discrimination and social injustice, reservation in public employment and public offices has been made.

Dr Ambedkar sought social justice from two sides—society and constitutional means. Equality before the law, abolition of untouchability and reservation in public employment and public offices for the members of the Scheduled Castes provides constitutional solution. In the realm of society, he struggled for social justice and waged movements and Satyagraha for seeking social rights of temple entry and access to water from public places. At one point of time during the independence movement, Dr Ambedkar demanded separate electorate for the suppressed castes to protect their social and political interest.

Concept of social justice against caste inequalities advocated by Dr Ambedkar was the solution for historical discrimination and injustice. Here social justice is not only concerned with distribution of benefits in society, but also removal of caste injustices, access to public places and temple entry and compensatory opportunity for public employment. As such, social justice in the Indian context and as Dr Ambedkar sought, means distributive justice in social, religious, civil and political arena. Dr Ambedkar was of the firm opinion that political democracy required social democracy and social equality and justice.

Liberal-Egalitarian Perspective on Justice

John Rawls and Justice as Distribution

It has been argued that due to behavioural and positivist emphasis on value-neutral and fact-based political theory, normative content of political theory has declined. In other words, it was felt that in the mid-twentieth century, there was less emphasis on the normative principle in political theory. This could be due to the elite theory criticizing the traditional understanding of democracy, behavioural rejection of ‘value based’ political theory, empirical model focusing on the political system as a mechanics instead of the state as a politico-social institution, etc. While empirical and positivist direction in political theory was visible, John Rawls's A Theory of Justice (1971) brought to the fore the normative content of political theory afresh. A professor of philosophy at Harvard University, Rawls argued for distributive justice and just distribution of primary goods in society. He argues that the Utilitarian conception of justice as ‘the greatest net balance of satisfactions’ is inadequate and offers contract based theory of justice that takes into account original position (state of nature), individual rationality and decision-making (social contract) into account. Before we discuss Rawls,s concept and principle of justice, let us summarize what it implies:

- Rawls combines liberal (liberty) and egalitarian (equality) arguments to present his concept of distributive justice, which he calls ‘justice as fairness’.29

- Rawls proposes that justice as fairness means certain principles which if followed would result in just distributive arrangements in society. This would be just because the procedure of distribution being followed is based on just principles.

- How do these principles work? For Rawls, principles of liberty and equality should be coordinated as basis to determine distribution of ‘primary goods’ or resources in society. These primary goods include basic liberties, rights, income, wealth, opportunities, offices, welfare.30 How does one get the just principles? He assumes a situation of ‘original position’ (like the state of nature of the social contract as a purely hypothetical and not a historical situation) in which human beings decide the principle of distribution. It is based on social contract assumptions.

- Why this is an original position? This is because the individuals (the decision-makers) are not aware of their class position, social status, intelligence, strength or skills and even the principle of good.

- In such a situation, principles of justice are chosen behind what Rawls calls, the ‘veil of ignorance’.

- Now, what Rawls has constructed is an original state of nature-like position in which individuals are not influenced by their ‘special psychological propensities’ or the idea of good or such differences as class, social and status distinctions or share in natural assets and abilities, intelligence, strength or merit. As such, everyone would work behind the veil of ignorance. He assumes that the individuals being rational decision-makers would make rational choices and devise principles which if followed would result in just distribution in society.

- If this is the situation, Rawls assumes that each individual would choose two principles: (i) equality in assigning basic rights and duties to all; and (ii) social and economic inequalities (of wealth and authority) are arranged in such a way that it results in compensating benefits for everyone and most of all, to the least advantaged.

- Based on these assumptions, Rawls constructs two basic principles of justice as fairness:

- First principle: ‘Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive basic liberty compatible with a similar liberty for others.’

- Second principle: ‘Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both (a) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged; and (b) attached to positions and offices open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity’.31

These are the two basic principles of fairness that Rawls proposes, which would result in justice if they were followed for distributive arrangement in society. The first principle can be called equality principle and the second as difference principle. While the equality principle is ‘concerned with citizens’ equal rights to basic liberties such as the right to vote, freedom of conscience, and so on’ the difference principle ‘is concerned with redistribution’32. To agree with Heywood, while the first principle proposed by Rawls reflects some kind of ‘traditional liberal commitment to formal equality’ the second ‘points towards a significant measure of social equality’. It appears that the equality principle gives priority to equal liberty for all; the difference principle involves two criteria that would determine the iniquitous distribution of material and economic rewards in society. Within the difference principle, the first criteria relates to material inequality when it makes everyone better off and works in favour of the least advantaged. This means that reward could be related to talent, merit and skills or abilities of individuals if and only if it works for the betterment of the least advantaged. Further, the second criteria within the difference principle implies equality of opportunity that allows talents and merits to compete but also includes a level playing field to compensate for initial distortion. Rawls's presumptions are in favour of equality and argue for inequality to the extent it does not distort the basic redistributionist principle. Thus, for Rawls, the basic criteria of distribution is not individual talent or merit or ability or deserts but needs for equal distribution of primary goods and the greatest benefit to the least advantaged through just outcomes. Why does Rawls feel that skills, talents or merits of individuals cannot be the basis of fair distribution?

Rawls's position is based on his criticism of negative or ‘natural’ liberty. Rawls feel that according to the negative system of liberty, positions are open to those who are able and willing to use their skill and talents in whatever way they choose. Here, personal negative liberty has priority and resultant outcome is considered just. Therefore, how people earn wealth or reward become important and not what wealth or reward they earn. According to Rawls, as Walton explains, in terms of negative liberty, ‘the distribution is just so long as it is acquired under conditions where people are (negatively) free to use their skills and talents …’33 Apparently, justness is a function of initial liberty in the negative sense and not of outcome. Rawls disagrees from the proposal that rewards should be in proportion to skills and talents. Rawls argues that skills and talent, to a large extent, are result of ‘naturally and socially acquired advantages’. These are contingently acquired talents. This means talents and merits are not possessions of individuals per se as negative liberalism holds but result of either natural endowment or fortunate family and social circumstances. The moot question, which Rawls raises, is that: should individual rewards or material benefits be allocated primarily based on contingently acquired talent or merits possessed by individuals?

Rawls treats these talent, merits, skills and abilities as common assets, which ought to be distributed on just principles. This means, talents and merits or skills themselves cannot be a basis of just distribution but would require a publicly related principle of distribution, which treats distribution of talents or merits of abilities as common assets. Rawls's argument against desert as the basis of distribution is that it is arbitrary to reward a person for contingently acquired skills and capacities derived from a social and natural advantageous position say, class or social positions. As an alternative, Rawls constructs the principle of justice that gives priority to needs than desert or entitlement based on talents or skills.

Critical evaluation

Rawls's A Theory of Justice was published at a time when American political and social milieu was covered with issues related to the Civil Rights and Black Liberation movements, Women Rights and Liberation movements, Anti–Vietnam War movements, etc. On the other hand, within the discipline of political science, behavioural and post-behavioural debate has also tilted towards relevant and action-oriented political science. Rawls's proposition of distributive justice and his work were considered as a welcome beginning in normative and value-oriented political theory. Rawls relates argument for liberties and equality to provide basis and justification for a liberal welfare state. Recognizing his contribution to political theory, Marshall Cohen says, ‘All the great political philosophies of the past—Plato's, Hobbes's, Rousseau's—have responded to the realities of contemporary politics, and it is therefore not surprising that Rawls's penetrating account of the principles to which our public life is committed should appear at a time when these principles are persistently being obscured and betrayed.’34 However, writers and thinkers such as C. B. Macpherson and Norman Daniel put him and his theory in the category of what Macpherson calls revisionist liberal, and Daniel calls a theory of liberal democratic justice. Though Rawls puts forward a formidable normative proposition on distributive justice, it has been responded to from many quarters with equal force. We can discuss the response from Brain Barry, Macpherson's evaluation of Rawls, the communitarian perspective of common good, Marxian perspective offered by Milton Fisk and Richard Miller and Nozick's libertarian reply.

After two years of publication of Rawls's A Theory of Justice, Brian Barry in his book, The Liberal Theory of Justice (1973) doubted Rawls's assumptions regarding rational persons choosing the two principles in the original position. Barry argued that ‘what he (Rawls) is doing is invoking a particular conception of rationality which is contestable’.35 However, it would be appropriate to point out that Rawls does not renegade on the liberal assumption of individual rationality and assumes that given a particular original situation as he portrays where the individuals decides behind the veil of ignorance, individual rationality would settle to choose an egalitarian society.

Crawford Brough Macpherson, who is considered as a radical democrat and who has criticized liberalism as ‘possessive individualism, offered a critique of Rawls's conception of distributive justice in his essay ‘Revisionist Liberalism’.36 He terms Rawls as ‘revisionist liberal’ and his model of distributive justice as ‘not adequate as a liberal-democratic theory’. Macpherson does not reject Rawls's argument of replacing Utilitarian justice with contractarian justice. He says, ‘I want chiefly to consider the adequacy of the model of a liberal–democratic society which he constructs from and justifies by his principles of justice’.37 Then, Macpherson goes on to dissect and criticize Rawls's basic premises, which accept inevitability of institutionalised inequalities within a class-divided society. Macpherson says Rawls accept that institutionalizsed inequalities, which affect life-prospects, are inevitable in any society. He is also critical of Rawls treating inequalities between classes by income and wealth. Macpherson feels that Rawls's model of a liberal–democratic society and two principles of justice are designed to deal with inequalities. But Rawls also accepts class division as inevitable. Having accepted the inevitability of class division, Rawls second principle tends to show or justify when class inequality in life prospects is justified. Macpherson ruefully comments, ‘Principles of justice designed to show when class inequalities are just do not go very deep.’38 Macpherson rejects Rawls's assumption that distributive justice is possible even within a class divided society. Macpherson in his books, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism (1962) and The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy (1977) has argued that a class divided society or a society with capital as the extractive power is inimical to the developmental power or moral freedom of those who do not own capital.