1

Approaches, Methods and Models of Political Study and Analysis

Introduction

The study of politics is inseparable from the debate on what constitutes the realm of the ‘political’. One may take the position that whatever goes into deciding the share of each human being out of everything human society as a whole owns, produces and possesses—both in terms of the material and the moral—relates to the realm of the political. If that is so, then should such sharing be on the basis of authoritative allocation by public decisions or through self-regulating private initiative? To decide this, we must understand the principle of distribution of resources: what should belong to each, and how this share should be organized. This, in turn, calls for an engagement with the principles of justice, rights, political and public obligations, and the arrangements that ensure decision making towards this end. Sabine opines that ‘the institutions in a society that we would be likely to designate as political represent an arrangement of power and authority’.1

This leads us to treat the political as encompassing the realms of both intellectual enquiry and practical activity. While in the first sense it means exploring the principles, values and objectives upon which a society can be organized, in the second it means analysing the processes of political activity and the arrangement of power and authority. In short, the former explores the ideal and the latter involves the practical. Various approaches to political enquiry highlight one or the other meaning. However, it may also be the case that the ideal and the practical are not always treated separately. The dichotomy between what it is and what it should be is not maintained and a holistic political enquiry is envisaged. Leo Strauss, a twentieth century political philosopher, rejects the differentiation between political science and political philosophy, and maintains that values should not be dissociated from political enquiry.

Analysis of Traditional Studies

In the traditional approach, the main focus is on exploring the ideals and principles of organizing society, and defining the relationship of the individual and the State in terms of political and public relationships. Plato's The Republic explores the principles of an ideal State, virtues of the philosopher king, principles of justice and education, and so on. Aristotle's Politics seeks to show the principles of an ideal State, polity, justice, and so on. Machiavelli's The Prince offers suggestions as to what virtues (Machiavellian virtues, no doubt) a king should possess or show, and how to acquire, maintain and possess kingdoms. Machiavelli, however, also marshals historical and empirical data to support his suggestions. Hobbes's Leviathan and Rousseau's Social Contract enunciate the principles of civil society. Hegel's Philosophy of Right deals with the key issues of law, politics and morality, and makes a distinction between the State and civil society. Bentham's An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation enunciates the hedonistic nature of man, centering on pain and pleasure as moving forces, and lays down the principles of utilitarianism. Marx and Engels's The Communist Manifesto envisions a classless society. Rawls's A Theory of Justice enunciates the principles of justice based on equalitarian liberalism. C. B. Macpherson's Democratic Theory: Essays in Retrieval stresses on moral and creative freedom as the organizing principle of the individual–state relationship.

All of these studies explore ideals, principles or universal values—what Sabine refers to as the ‘disciplined investigation of political problems’.2

We may cite a second set of explorations that focuses on analysing empirical and/or historical data relating to political institutions, political practices and constitutional law for the purposes of making comparisons, suggestions or generalizations.

Aristotle's famous analysis and classification of the 158 constitutions of Greek city-states in the fourth century BC, wherein he attempts to find the best possible political set-up. Jean Bodin's analysis of the location of sovereignty in classical and contemporary political regimes in his The Six Books of Commonwealth where he shows absolutism to be the best of all defensible regimes.3 Charles-Louis Montesquieu's comparative analysis of political and legal issues based on political and social institutions of Europe in his The Spirit of the Laws, and his advocacy of separation of powers. Walter Bagehot's The English Constitution, in which he presents an analysis of the working of the political process.4 A. V. Dicey's Introduction to the Law of Constitution, in which he studies constitutional law and legal institutions. James Bryce's Modern Democracy, in which he analyses and compares the features of democracy, and the absence or presence of its ‘favouring conditions’, in six democracies—Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, Switzerland and USA—and compares them with other forms of government such as monarchy and oligarchy.5 Ivor Jennings's British Constitution, Cabinet Government and Party Politics, and K. C. Wheare's Modern Constitutions, Legislatures and Federal Government, which focus on political institutions. Karl Popper's The Open Society and its Enemies, in which he rejects Hegel (historicism/dialectical idealism), Marx (dialectical materialism), Spengler (cyclical change) and others, and insists that any hypothesis, to be valid in a scientific manner, must be open to verification through observations.

Analysis of Recent Studies

While the classical and traditional political studies focused on universal principles and ideals, and legal–institutional arrangements, a new stream of studies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, focused more on the processes—both formal and informal, which influence and condition the working of political institutions and decision-making in the political arena. An important development was the stress on the behavioural aspects of political studies. The emphasis on individual and group actors, informal processes, and factual and observational techniques gave birth to the behavioural approach. An important contribution was also the growth of the inter-disciplinary approach in which the disciplines of psychology and sociology were used for political analysis. The following studies, which rely on experimental, empirical and scientific methods, constitute the contemporary approach.

Arthur F. Bentley's The Process of Government, which discusses informal processes and not descriptive formalism or formal political institutions; his study largely provides the basis for understanding the actual dynamics of groups in politics—pressure groups, political parties, public opinion and elections. Borrowing also from the field of sociology, Bentley's group approach to politics stresses the ‘functional basis of government’, i.e., politics is understood in terms of group conflict, with the government playing a balancing act.

Graham Wallas's Human Nature in Politics, in which he emphasizes the informal processes affecting political institutions and decision-making; he borrows from the field of psychology and shows that human beings are not always rational or guided by self-interest in their activities. He holds, ‘that to understand the political process one must examine how people actually behave in political situations, not merely speculate on how they should behave or would behave.6 According to Wallas, neither the deductive method adopted by Hobbes and Bentham, in which human beings are seen to be self-interested or moved by pain and pleasure, respectively, nor that of the political economist, in which human beings are held to be rational, can be the basis for understanding political processes.

David Truman's The Governmental Process: Political Interests and Public Opinion, in which he furthers the thesis of group politics and explains political processes in terms of the interests and conflicts of various groups.7 Robert Dahl's theory of polyarchy is an extension of this argument.

Charles Merriam's New Aspects of Politics and Political Power, Harold Lasswell's Politics: Who Gets What, When and How, A. Kaplan's Power and Society: A Framework for Political Enquiry, all of which dwell on the elite theory argument that politics is actually the interaction and negotiation amongst a variety of political elites.

The second stage of the development of political studies can be illustrated through the following works.

David Easton's The Political System, in which the systems approach is emphasized, i.e., how inputs in the form of pressures and demands are received by the political system from society, how they are considered and processed for decision-making (authoritative allocation of resources) and how outputs (decisions) are rendered. Easton defines the political system as ‘that system of interactions in any society through which binding or authoritative allocations are made’.8

A particular variant of the general systems theory is the structural–functional theory that seeks to investigate which political structures perform what basic functions. Gabriel A. Almond and J. S. Coleman's The Politics of Developing Areas and Gabriel A. Almond and G. Bingham Powell Jr's Comparative Politics: A Developmental Approach develop and explain the structural–functional theory. While the behavioural approach is useful for the analysis of national governmental processes, the systems and structural–functional approaches help in comparative political analysis. A more inclusive approach is adopted by Gabriel A. Almond, G. Bingham Powell, Jr, Kaare Strom and Russell J. Dalton in Comparative Politics Today.9

Karl Deutsch's The Nerves of Government, Models of Political Communication and Control propounds the communication theory; the influence of science and economics is evident in the emphasis on channels, loads, load-capacity, flows, lag, etc. which set limits on any organization.

Anthony Downs's An Economic Theory of Democracy and J. M. Buchanan and G. Tullock's The Calculus of Consent treat political processes as processes of exchange. These works draw upon the economic postulate of the self-interested and rational individual to put forth the new political economy approach that seeks to apply economic models to the study of politics. Anthony Downs, Mancur Olson and William Niskanen have applied the new political economy approach to the study of party competition, electoral and voting exchange, interest group behaviour and policy influence on bureaucrats. Two specific applications of the theory have been in the form of the rational or public choice theory that understands political issues in terms of rational, self-interested individual behaviour and the game theory understood in terms of the famous prisoner's dilemma.

Richard C. Snyder, H. W. Bruck and Burton Sapin's Decision-Making as An Approach to The Study of International Politics introduced decision-making as an analytical tool based on process analysis and capable of dealing with dynamic situations of time and change.

Approaches and Methods

Notwithstanding the flexibility with which the two terms, approaches and methods, are employed in the study of the social sciences, particularly political science, they must be differentiated to clearly understand their usage and scope. According to J. C. Charlesworth, we must differentiate ‘between an approach as a method and an approach as an objective’.10 Some approaches are mere manifestations of the objectives to be achieved. For example, the basic objective of a pluralist approach is to provide a critique of the monist theory of sovereignty and assert the idea of pluralist autonomy. This is an example of an approach as an objective. On the other hand, some approaches are methodological and aim to ‘weigh, count and measure the doings of real people’.11 Thus, according to Charlesworth, approaches can be objective-based or method-based.

The term approach refers to a perspective or vantage point from which a subject matter is treated or looked at. It is a particular way of understanding something. It is generally associated with the question, what to inquire or study. For example, one can explore a political ideal like the principle of justice or right (normative–prescriptive approach); study political and legal institutions that are part of political arrangements (legal–institutional approach); understand political processes through the forms of negotiations, bargaining, decision-making (behavioural approach); or treat political arrangements as being part of the political system (systems approach), and so on.

Method, on the other hand, refers to a particular way of doing or solving something. As such, it is a body of systematic techniques to explore a subject matter. It is generally associated with the question, how to inquire or study. For example, one can form generalizations or conclusions from observable instances and particular observations (inductive method); draw inferences and particular references from general principles (deductive method); find conclusions by comparing different observable instances (comparative method); draw general inferences from observations and factual data (empirical/experimental/observation method); construct the shape of ideal political institutions based on philosophical and ethical grounds (philosophical method); analyse historical data to reach certain conclusions to be applied in present circumstances (historical method); understand political processes based on observable behaviour of actors, individuals, groups, etc. with scientific techniques and tools (scientific method); or analyse contemporary situations and its observable behaviour based on historical evolution (method of dialectical materialism/Marxian analysis).

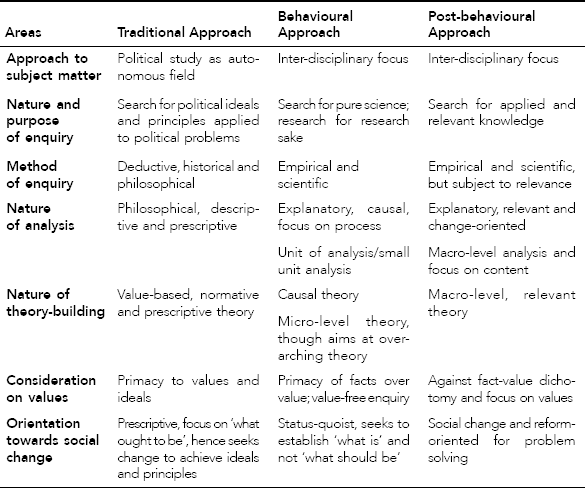

Although, generally, a particular approach is associated with a particular method of enquiry, an approach may adopt more than one method of enquiry. As such, a method may be associated with more than one approach. For example, the historical approach can employ the historical method as well as comparative and empirical methods. The Marxian approach adopts the method of dialectical or scientific materialism, which involves both the historical as well as dialectical methods. Table 1.1 sets out the relationship between approaches and methods in the traditional and contemporary contexts.

Table 1.1 Differences/Similarities in Approaches and Methods

Generally, a distinction is made between traditional and contemporary approaches and methods. This relationship between approaches and methods needs to be understood first. There are some methods that are employed in both traditional as well as contemporary approaches of study and analysis, whereas some methods are associated with one (or more) approach. It is also maintained that while some approaches and their methods of exploration help in building political theory, some others are inimical to generalization and political theorization. This has led to a debate on the decline and resurgence of political theory. To understand these issues our survey and analysis can be arranged in the following order:

- Relationship between approaches and methods

- Traditional and contemporary approaches and methods

- Debate on the decline and resurgence of political theory

Traditional Approaches and Methods

Philosophical Approach

The philosophical approach, as the name suggests, treats political issues as philosophical concerns. Its main concern is to find out what should be or ought to be the principles, ideals and organizing criteria of political and human society.

The Greek thinkers espoused, and enquired into, philosophical issues. In the writings of Plato and Aristotle we find philosophical concerns, such as the proposition of an ideal State/society, principle of justice, and so on. From this concern for the ideal, the philosophical approach becomes prescriptive and normative, and reflects ethical concerns. For example, in Plato's search for the philosopher king and principle of justice on which to organize his republic. Similarly, Aristotle's assertion that the State alone is self-sufficing and it alone can provide conditions within which the highest development of human beings can take place reflects the same concern. For him, self-sufficiency of the State goes beyond mere territorial or economic self-sufficiency, and stands for moral and ethical self-sufficiency. It is this that leads him to say that the State comes into existence for the sake of life and continues for the sake of good life. Further, when Aristotle says, and the Greeks agree, that man is a political animal, it indicates that for them political life was the very end, the teleos of human existence. Barker sums up this concern of the Greeks when he says, ‘The nóλις (polis) was an ethical society; and political science, as the science of such society, became in the hands of the Greeks particularly and predominantly ethical.12 Thus, political science became concerned with ethical issues and not merely superficial arrangements of offices.

The philosophical approach generally adopts the deductive method and seeks a priori or universal principles. It draws conclusions or prescriptions based on these principles. The existing arrangements, political set-up and public offices are judged according to the conclusions drawn from the universal principles. According to Plato, ‘Knowledge of the proper use to which any branch of knowledge should be put is a master knowledge’. And he identified this with the art of politics, or political science.13

According to Sabine, political theory is associated with the ‘philosophic–scientific tradition’ and has been characterized by ‘architectonic’ stance with respect to its subject matter. ‘A political theorist stands outside the edifice as an architect might … sees it as a whole, plans its whole development, and adjusts this or that aspect with an eye to the success of the whole.’14 This ‘whole’ has to come from a priori principle(s) and universal values to which the practical aspects can be adjusted. This shows that values and universal principles should not be isolated from political enquiry.

Contemporary thinkers such as Leo Strauss have insisted that philosophy being the quest for universal knowledge, political philosophy is an ‘attempt to know both the nature of political things and the right, or the good, political order.15 He believes that political science is concerned with not only arrangements but also values. Thus, values are integral to political philosophy, and political philosophy is integral to political thought and, hence, to political enquiry. He is very critical of the distinction made between political science and political philosophy, and the fact–value dichotomy being maintained as a result of this distinction. Like Strauss, Eric Voegelin also supports philosophical political science as the search to understand what a good citizen and a good society are.

Medieval theorists like Thomas Aquinas also reflected the themes and ideas of the Greek political theorists. Aquinas defined society as ‘a system of ends and purposes’,16 and insisted on the moral aspects of governing and authority. Immanuel Kant's concept of ‘human dignity’ where he asserts that an individual should be treated not merely as a means but also as an end is a philosophical enquiry. The concept of ‘moral or self-development’ found in J. S. Mill, T. H. Green and C. B. Macpherson also raises philosophical questions. In fact, the philosophical approach seeks the moral basis of political obligation and legitimacy of authority. Rawls's distributive theory of justice and Nozick's entitlement-based theory of justice both seek justice, though in different ways.

The empirical and behavioural theorists criticize the philosophical approach for being speculative and subjective, and maintain that there is a dichotomy between facts and values. They believe that all political enquiry should be fact-oriented, not value-based.

Historical-Analytical Approach

If history is the narrative of past events, a systematic record of what happened, then it is also the story of how political institutions came into being, how they evolved, what principles went into organizing them and how they changed over time. The historical approach attempts to present a historical account of political thought and theory. Sabine, for example, in his A History of Political Theory seeks to present the history of political theory as a ‘disciplined investigation of political problems’. These political problems are problems of ‘group life and organization. He discusses the major themes that have appeared in the writings of thinkers such as Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Bodin, Althusius, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Bentham, Mill, Green, Hegel, Marx, and others. Ivor Jennings traces the growth of the office of the Prime Minister in Britain and the institution of political parties by using the historical method. In a limited sense, the historical approach can help:

- To study the emergence of ideas, institutions and values.

- Analyse the relevance of ideas, institutions and values for the contemporary period and seek guidance for the future.

- Make comparisons in the context of historical backgrounds; according to Garner, ‘It is almost a commonplace to-day to affirm the necessity of historical study as a basis for the scientific investigation of political institutions which have a historical background.’17

- Draw inferences or tentative conclusions with respect to some aspects of contemporary political activities with the help of the historical–descriptive technique.18

The historical approach applies ‘historical and inductive methods of enquiry to draw conclusions by observing one or more sets of events and historical activities.’19 In yet another sense, the historical approach has served as a method of analysing historical events by way of tracing historical laws, i.e., history is viewed as a process determined by its own inherent necessity beyond the control of human initiative. Hegel's historical dialectical method and Marx's historical materialism are examples of this approach. Hegel seeks to present history as the history of the ‘spirit’ and its journey to realize perfect freedom. The State for him is the culmination of this journey. For Marx, history is understood in terms of the replacement of one mode of production or economic relationship with another, to establish a classless society. Critics have expressed apprehension with respect to the historical approach both as a historical–descriptive analysis and as a way to discover historical laws. According to R. H. S. Crossman and Karl Popper, the historical approach is suitable only to study particular phases of ideas and institutions, without being relevant to the study of contemporary institutions and values. It is in this sense that Fredrick Pollock remarks: ‘The historical method seeks explanation of what institutions are and are tending to be, more in the knowledge of what they have been and how they come to be what they are, than in the analysis of them as they stand.’ David Easton ruefully opines that contemporary theorists, instead of formulating a new value theory, are engaged in historicism, i.e., simply relating information about the historical development of contemporary and past values. This, in turn, has hindered the formulation of a value theory suited to contemporary requirements. In fact, the historical approach has been responsible for the decline of political theory.

Further, in seeking comparisons on a historical basis, there could be danger of superficial resemblances and historical parallels, against which James Bryce warns. By applying the inductive method of reaching inferences through observations, the historical approach can provide empirical bases but there could also be problem of confusing what Seeley calls, ‘what ought to be with what is’.20 The investigator's own biases and locational (social, cultural and geographical) conditioning may also affect historical analysis. By seeking value in historical events and activities, this approach may lead to conservatism and, at times, retrograde formulations.

Popper also criticizes the historicism of Hegel and Marx. According to Popper, having established what is inevitable, historicism results in advocating the means to achieve it that may also be authoritarian. He declares them to be the ‘enemy of open society’ and inimical to ‘social engineering’, the means of social change for a liberal society.

Legal–Institutional Approach

The legal–institutional approach is concerned, first, with the study of political institutions such as the State, legislature, executive, judiciary, office of the prime minister, cabinet, etc. And, second, it deals with the study of constitutional law, legal position of institutions, and concepts with juridical implications, such as legal sovereignty, separation of powers, rule of law, and so on. In fact, as Alan R. Ball says, ‘the study of constitutional law formed a very important cornerstone of traditional political studies’.21 The study of legal institutions becomes an important element in political study. Dicey's Law of the Constitution and Bagehot's The English Constitution are two representative British studies of the constitutional law approach.

In the Indian context, Granville Austin's The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation presents an account of ‘development of the constitutional democracy in India’. Austin opines that the Indian Constitution was envisaged by the Constituent Assembly as a design for achieving many goals, transcendent among them being that of social revolution.22 He suggests that the decisions to adopt a parliamentary government and attendant political structure were part of this larger goal. Austin calls his study the ‘political history of the framing of the Constitution’ and distinguishes it from other studies that he says have ‘a more legalistic approach’.23 The juridical method of study in which, according to Jellinek, the contents of the rules of public law are determined and conclusions deduced, can be treated as part of this approach. Social and political relations are seen in terms of public law, rights and obligations, and the State is treated as a corporation or juridical person. As such, the State becomes an organization for the creation and enforcement of law. This method views political science as a science of legal norms.24

In India, the legal approach to the study of the Constitution and political set-up would deal with the legal implications of the provisions contained in the Constitution of India, such as the Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles of State Policy, the federal provisions regarding the division of powers between the Union and the States, the functions and powers of president/governor, prime minister/chief minister, cabinet and council of ministers, etc., the implication of the separation of powers between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary, the bodies and agencies that legally and constitutionally constitute the ‘State’ in India, and so on.

The legal–institutional approach, though helpful in understanding political institutions and legal implications, is limited by its focus on formal structures and arrangements. Merely studying the organization of a government and its organs in constitutional and formal terms cannot give a full picture of the complexity of political processes. To fill the gap, a new trend focuses on studying the informal political process such as political parties, pressure and interest groups, and group behaviour in politics. The concept of the State as a juridical person also has a limited use in understanding its meaning and role in contemporary times. A welfare State, for example, is not merely a law-enforcement agency but performs what may be called cradle to grave functions.

Descriptive-Taxonomic Approach

The description and classification (taxonomy) of political institutions has also been an important approach in political study. For example, Aristotle classified governments on the basis of type of constitutions/governments; Bodin on the basis of location of sovereignty; Bryce on the basis of type of democracy; and Wheare on the basis of levels of government.

Some studies have also focused on the normative–prescriptive aspects of political institutions—the merits and demerits, or the advantages and disadvantages of the parliamentary as against the presidential system, and the unitary as against the federal government, and so on. The preference for one system over the other is based on observable functions and requirements. For example, a federal government may be seen to be an appropriate system of organizing power where society is diverse and requires accommodating different interests in a society. In the USA and India, historical and political reasons, and cultural and linguistic factors, have respectively necessitated a federal structure.

The descriptive–taxonomic approach does apply some kind of an empirical and comparative method. Aristotle's description of 158 constitutions was based on their actual working. Ivor Jennings analysed the working of the British cabinet and James Bryce analysed democracies by observing their actual working.

The descriptive-taxonomic approach, by applying the empirical method of collecting data and classifying facts, introduced a scientific and observational method of political analysis even within the traditional fold, thus representing a shift from the normative to the empirical mode. Nevertheless, this approach, although hinting at the study of processes and informal aspects of governments, largely remained confined to the study of formal institutions. Second, the description and classification of institutions was Euro-centric. Third, the empirical method used in the descriptive–taxonomic approach was less rigorous, as can be seen by making a ‘comparison between the tools of analysis used by Bryce and Almond’,25 for the studies of democracies and political cultures, respectively. Data collection and analysis, though based on the empirical method, was more in the nature of personal observations and insights, than verifiable scientific evidence.

Contemporary Approaches and Methods

Contemporary approaches to political study are functionally oriented, behavioural and fact-oriented. While traditional approaches largely rely on philosophical, deductive, historical and, in a few cases, comparative and empirical methods, contemporary approaches are based on scientific and empirical methods, and use statistical and quantitative techniques. Thus, both in their focus and scope of study, as well as in the techniques and tools used, contemporary approaches are revolutionary. We will discuss these approaches and methods, and their implications for the study of political science.

Behavioural Approach

In the first half of the twentieth century, a visible shift in the study of political science was seen in the writings of those who stressed on the role of human nature and psychology in politics, the role of informal structures and their influence on formal political institutions, and the study of processes rather than institutions. This approach, called behaviouralism, may be understood in terms of two basic trends in the study of human (or animal) behaviour or psychology—behaviourism and behavioural science. Behaviourism is concerned with the study of psychology that concentrates exclusively on observing, measuring and modifying behaviour. Behavioural science is concerned with the ways in which people behave, and it uses scientific methods to study such behaviour. Behavioural science generally includes anthropology, psychology and sociology.26 According to Charlesworth:

[Behaviouralists] … conclude that the only way to understand him [man] is to observe him and record what he does in the courtroom, in the legislative hall, in the hustings. If enough records are kept, we can predict after a while (on an actuarial basis) what he will do in the presence of recognized stimuli. Thus we can objectively and inductively discover what and where and how and when, although not why?27

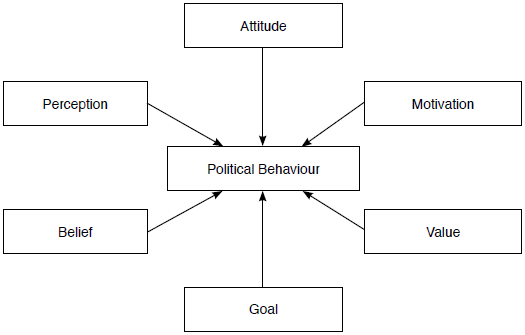

David Easton has differentiated between behaviourism and behaviouralism.28 He suggests that behaviourism stands for observable behaviour as a result of external stimuli. This can be understood as the stimuli–response (S–R) paradigm where only observable data as a response to external stimuli is treated as valid. For example, the sudden touch of heat or fire produces a reaction by which one distances oneself from the source of it. The external stimuli being heat and the response being distancing, one may be concerned with only the reaction when one goes closer to heat. Behaviouralism, on the other hand, while observing behaviour as a result of external stimuli does not rule out subjective experiences such as motivation, feelings, purpose, desire, intention or ideas while observing responses (see Figure 1.1). Behaviouralism is understood as the stimuli–organism–response (S–O–R) paradigm where subjective experiences of human beings are also taken into account for political analysis. For example, the democratic process being a stimulus and voting a response, an electorate (organism) may be influenced by a variety of subjective and value factors such as caste, class or political affiliation.

There appear to be two trends within the behavioural approach—one which focuses only on observable, countable, measurable behaviour that can be reduced to quantifiable and testable data, and the other that suggests that political analysis should not concern itself merely with measurement and quantification, but also with theory-building. To understand these trends, we may briefly discuss the growth of the behavioural approach. Some writers have traced three phases of the behavioral approach.29 The first phase is identified with the pre-Second World War trend in political analysis when empirical and quantitative methods along with statistical tables were used, an improvement over the previous descriptive approach. However, these techniques and methods were only aimed at presenting description and analysis in a more refined way. Harold Lasswell's use of content analysis and psychoanalytical theory constitute an important contribution in this phase. However, after the Second World War, a second phase was discernable. Political analysis during this phase was characterized by the use of empirical methods and quantitative techniques by Almond, Powell, Dahl, Easton, Deutsch, Lasswell and others. It was during this period that systems, decision-making, communication, structural–functional and other such models and approaches were developed. Further, this period also saw a great leap in the use of a variety of techniques of research, data-gathering and analysis. The idea in this phase was that empirical research would lead to formulation of hypothesis or propositions which, in turn, could be further tested rigorously by employing various research techniques. As a result, there was so much emphasis on scientific tools and techniques that the behavioural approach became identified with technique and method at the cost of theory-building. Behaviouralists became divided into two schools: one supporting theory-building with less emphasis on findings—theoretic behaviouralists; and the other concerned with methods and techniques at the cost of theory or even political science itself—positive behaviouralists. A balance was to be found in the form of research informed by theory and theory based on data.

The ‘Intellectual Foundation Stones’ of Behaviouralism: David Easton

Behaviouralism in political analysis has represented different things to different people—a methodological or technical orientation; a search for stable units of political analysis in the form of individuals, groups, processes, functions, structures, political culture, communication, decision-making, etc.; a movement or revolution in political analysis.

David Easton has laid down eight assumptions and objectives of behaviouralism, which he terms as its ‘intellectual foundation stones’.

Regularity

Regularity refers to the frequency, periodicity or uniform interval of occurrence of an activity or phenomenon. In the natural sciences, observable phenomena are available for empirical testing due to their occurrence at regular intervals. As such, a causal relationship between an event or activity and its cause (cause–effect relationship) can be established. Behaviouralists believe that there are discernible uniformities in political behaviour as human beings do behave in a similar manner when the circumstances are similar. Voting behaviour could be taken as a plausible example, meaning that there can be regularity in the voting pattern of a group of voters. The upshot of this argument based on the regularity assumption is that political behaviour due to discernible or observable uniformity can also be expressed in a generalized manner. As such, construction of theories is possible, which can explain and help in predicting political phenomena. For behaviouralists, political study and political analysis must seek regularity in political behaviour, such as voting pattern and pressure tactics, and locate variables associated with them, such as social affiliation, economic status, resource allocation through public policy, etc.

Verification

Verification stands for checking the validity or veracity of a statement, proposition or theory. Behaviouralists believe that generalizations arrived at by observing regularity in political behaviour must be testable. This means that political propositions must be subjected to empirical test/s with reference to the relevant political behaviour. Therefore, all that political science or political analysis should aspire for is to concern itself with observable phenomenon. For example, if there is a proposition that says that voters in the high-income group tend to vote for conservative parties, this must be valid when tested with reference to the voting behaviour of high-income voters.

Techniques

For observing, recording and analysing political behaviour, and generating valid, reliable and comparable data, rigorous techniques are required. For the purpose of acquiring valid and reliable data, behaviouralists focus on the methods of questionnaires, structured interviews, content analysis, statistical sampling techniques, close-ended surveys, and so on. Sophisticated research tools such as simulation, causal modelling, multivariate analysis, scalogram analysis, paired comparison, etc. are used for the analysis and interpretation of data.

Quantification

In scientific enquiry, quantification is considered to be a very important step towards making data measurable. To say that out of an electorate of 1 million a large number voted for party X, is not the same thing as saying that out of 1 million 60 per cent or 60,000 voted for party X. To quantify is to precisely determine the number or the amount or the degree of something. For behaviouralists, quantification and measurement are important for eliminating the factor of qualitative and personal intervention in recording, interpreting and analysing data. Any error or unreliability in data so quantified can be corrected with the help of verification.

Values

Prescriptive and ethical evaluation has been associated with theory-building in traditional political inquiries. Behaviouralists, on the other hand, try to make a clear distinction between ethical evaluation and empirical explanation. They advocate value-neutrality in political enquiry. While the deductive and prescriptive mode of traditional political enquiry is based on the search for ethical and universal values, behaviouralists look for empirical explanations based on observable behaviour. The whole debate between behaviouralists and traditionalists has revolved round the fact–value dichotomy. Behaviouralism is not concerned with value judgment and focuses only on factual propositions. Behaviouralists advocate that political enquiry to be objective should be value-free and value-neutral. For example, principles like liberty, equality or justice are normative values whose truth and falsity cannot be established empirically. In short, behaviouralists advocate value-neutral, factual, explanatory–descriptive political enquiry, as against traditional political enquiry that is normative, value-laden and prescriptive.

Systematization

Behaviouralists seek to bring the rigour of empirical and scientific techniques to research in political science. But research should not be an end in itself; it should be linked to theory. Behaviouralists seek to relate research and theory, because, ‘research, untutored by theory, may prove trivial and theory unsupported by data, futile’.30 In traditional political enquiry, theory tends to be become speculative and normative. Behaviouralists, unlike traditionalists who emphasize the value theory, give importance to the causal theory. A value theory, for example, Plato's proposition that only a person who personifies the Idea of Good can be a philosopher king, is based on the deductive method, on normative and prescriptive principles; a causal theory, on the other hand, seeks a functional relationship between variables. For example, the social and economic background of a group of voters and their voting preferences are all variables that are linked to each other. For behaviouralists, only causal theory is important.

Behaviouralists talk of a hierarchy of theories. Low-level theory explains relationships at a simple level and attempts singular generalizations. Middle-range theory represents synthetic or narrow-gauge theory. General theory represents systematic or overarching theory. Though behaviouralists aim to discover general laws of political behaviour and formulate overarching theories as their final goal, they start with low-level or middle-range theories.

Pure science

The pure science approach of behaviouralists means that the understanding and explanation of political behaviour are important for utilizing theoretical knowledge to solve urgent political problems. The emphasis is on pure research even if it cannot be applied to specific and minimum social problems. In short, it is research for research's sake. Their quest is ‘to observe, analyse and organize facts with supreme and cold aloofness’. Excessive concern with facts or hyper-factualism has, however, been criticized as leading to crude empiricism, i.e., collecting data for data's sake.

Integration

Behaviouralists argue that the study of cultural, economic, psychological and social phenomena, the inter-disciplinary approach, is important to understand political behaviour in its proper context. The search for unity and integration of the social sciences has prompted the search for ‘stable units of analysis’ that can be used across the disciplines. General systems, actions, functions and decisions have been proposed as units of analysis that are equally relevant for analysis in different disciplines.

One of the important examples of the inter-disciplinary approach is the field of political sociology that studies how the political and the social interact with and affect each other. Rajni Kothari's study of the interaction between politics and caste in India and his famous statement that ‘the alleged casteism in politics is thus no more and no less than politicization of caste’31 can be treated as a study within the inter-disciplinary/political sociology approach. Besides Kothari, the studies of Paul Brass, Ramashray Roy and others on the interaction between caste and politics in India, especially from the point of view of ‘factionalism’, follow this approach.

Traditionalist Critique of Behaviouralist Assumptions

Those who favour the traditional approach have criticized the regularity assumption of behaviouralists, arguing that political reality is not uniform, and human nature and behaviour cannot be uniformly or regularly expressed. Further, human nature and behaviour are not amenable to objective study and as such no generalization is possible. Given the large number of social, cultural, economic and emotional variables, and also historical contingencies, regularity may not plausibly be achieved. Even if a general statement of regularity is achieved, the so-called scientific prediction based on regularity cannot go beyond the ‘if-then’ proposition.

The traditionalist argument against the verification assumption is that verifiable political behaviour constitutes only a small part of the whole political behaviour. By limiting political phenomenon in terms of only what is observable, behaviouralists in fact limit the scope of political science. Human behaviour is contextual and is also determined by institutional and social settings in which it occurs. As such, knowledge of the setting is essential. By focusing only on observable and verifiable political behaviour, behaviouralists ignore what lies beneath surface dynamics.32 Traditionalists feel that by ignoring non-observable and sub-surface dynamics, behaviouralists actually harm the cause of political science and limit its scope. The excessive emphasis by behaviouralists on empirically testable and verifiable propositions and hypotheses has led to the positivization of political science. This means that political enquiry has been limited to only whatever is testable and verifiable by external observation through the senses, and theory-building has suffered.

Traditionalists hold that techniques should not be exalted at the cost of content. By overemphasizing techniques, behaviouralists try to make political science fit sophisticated techniques. They study only those areas that are amenable to the techniques they advocate. Traditionalists question whether the technique applied by behaviouralists defines political science or whether the content of political science should define the technique. They settle for the latter.

Traditionalists object that behaviouralists attempt to quantify the unquantifiable and measure the unmeasurable. Political science deals with the very many significant questions and political problems that are neither amenable to quantification and measurement, nor required to be so.

Traditionalists feel that political science is concerned with values and ethical issues. Therefore, the search for value-neutral political enquiry is not desirable. They further hold that it is difficult for researchers to keep their preferences and value judgments away from their study. However, behaviouralists respond that by declaring their value preferences beforehand, this concern can be taken care of.

With respect to systematization, traditionalists argue that when low-level and middle-level theories are lacking in political science, it is premature to talk about overarching theories. Robert Dahl believes that ‘political theory in the grand manner can rarely, if ever, meet rigorous criteria of truth. In fact, in the search for general theories, behaviouralists have put forward various concepts and conceptual frameworks that are yet to be successfully operationalized. It can be said that the behavioural approach is limited in terms of its contributions to substantive research and theory.

Traditionalists have criticized the emphasis on the pure sciences by behaviouralists. Traditionalists hold that theory has no value unless applied to solving political problems. Crude empiricism is futile, and politically and socially irrelevant. They argue that applied research must get priority.

With respect to integration, traditionalists feel that the inter-disciplinary approach is useful in understanding political phenomena. However, they are apprehensive of the extent of influence of other social sciences on political studies and argue for the need ‘to preserve the identity, integrity and autonomy of political science.33

While it is true that there is an effort in all the social sciences to be more scientific and inter-disciplinary34 and as David Easton says, the behavioural approach represents a revolution both in technique and substance; it is more revolutionary in the field of technique and method than in the field of theory. Other limitations have been pointed out by political scientists and writers such as Heinz Eulau, J. C. Charlesworth, Leo Strauss, Mulford Sibley and Arnold Brecht, among many others.

Heinz Eulau feels that seeking regularity in the behaviour of individual actors does not automatically lead to generalizations or meaningful statements about the larger system. Given the fact that political science is interested not only in individuals but in the actions and policies of groups, institutions and states, the question arises as to how meaningful statements about larger systems can be made on the basis of enquiry into the political behaviour of individual actors. He hints at the problems that arise from the ‘fallacy of extrapolation’ when conclusions drawn from a study at a lower level are applied at the higher level. Second, he maintains that ‘it is necessary to distinguish between study of political behaviour and behavioural study of politics’. For the study of political behaviour, it is not necessary to use the concepts and methods of behavioural sciences. The only requirement is that the individual actor whose behaviour is described should be the empirical unit of analysis. In the behavioural study of politics, however, though the individual remains the unit of empirical enquiry, the theoretical units of analysis are groups, institutions, political culture, and so on. The behavioural approach has limited focus in terms of units of analysis and cannot explain processes and decision-making involved in complex institutional networks such as the State. Further, by focusing too much on processes and small groups or face-to-face behavioural aspects, it tends to neglect formal political institutions. While the importance of sociological factors like class, caste and ethnic factors in the sub-discipline of political sociology is appreciated, it should not be at the cost of ignoring the study of formal political institutions. While pressure groups, political parties, voters, public opinion, etc. are seen as ‘inputs’ of the political system, factors like government, legislature, executive, judiciary and bureaucracy are ignored.

J. C. Charlesworth, responding to the emphasis by behaviouralists on countable, quantifiable and measurable data, maintains that there are some very important elements in human nature like love, courage, patriotism, and so on, which are neither predictable nor measurable. ‘Behavioral studies are highly desirable to supplement other studies, but like all identifiable methodological approaches they are only part of the whole study of government and politics.’35

The behavioural approach may also fail to adequately account for various formal institutions due to its focus on informal processes, and as such it must be supplemented by other approaches.

Leo Strauss has criticized the behaviouralist approach due its fact–value dichotomy. He rejects the differentiation between political science and political philosophy and treats the latter as an integral part of the tradition of political thought. He is strongly critical of the behaviouralist approach, which he says ‘views human beings as an engineer would view material for building bridges’.36

Mulford Sibley has hinted that behaviouralism is not adequate in itself for understanding politics. He insists that values precede investigation and the investigator must have some notion of his/her own priorities before proceeding to use the behavioural approach. Behaviouralism can be used within a framework of value judgments, which are beyond behavioural techniques.

Further, the behavioural approach, by treating political phenomenon in terms of sociological or psychological categories, can reduce politics to ‘sub-politics’. Due to politics being seen as ‘a satellite of sociology’, it is seen as dependent on forces outside the political system. Therefore, it is important to demarcate the political boundary before attempting integration and inter-disciplinary study. Political analysts like Giovanni Sartori insist that political factors such as governments and parties affect political behaviour independently of sociological factors.

Arnold Brecht, like other neo-positivists, insists on the inevitability of value judgments in scientific investigations. As Brecht points out, without value judgment no end can be decided. At least at two levels the behavioural approach cannot avoid the involvement of value: setting goals that we seek as ends, and value preferences of the observer as regards what he/she thinks is significant for study.37 A charge from the Marxian perspective is that the behavioural approach insists on superficial social divisions and formations like elites, groups and parties and underplays the more acute class divisions. By doing so it serves the purpose of ‘stability’ and status quo. By its focus only on observable behaviour, the behavioural approach seeks to do nothing about the existing political arrangements, ‘which implicitly means that the status quo is legitimized’.38 Even the concept of democracy is not understood in terms of any value or equality, but is redefined in terms of struggle between competing elites, or what Dahl calls ‘polyarchy’. The traditional meaning of democracy is adjusted to subject it to the observable behaviour of groups, elites and individuals.

Achievements of the Behavioural Approach

Subjective awareness

The behavioural approach should not be understood only in terms of behaviourism. It is not only concerned with the behaviour of actors but also with their subjective awareness and individual orientations. These individual orientations involve components such as the cognitive (relating to knowledge of political objects), affective (feeling of attachment, involvement, rejection about political objects) and evaluative (judgment/opinion about political objects) aspects.39 The study of behaviour in terms of political behaviour is not merely concerned with directly observable political action, but also with those aspects that relate to perception, attitudes and motivation. As depicted in Figure 1.1, political behaviour takes place in an environment of a host of subjective factors. Behaviouralism, as David Easton says, takes into account subjective awareness. In fact, as Almond and Powell have indicated in their study, political culture refers to the pattern of individual attitudes and orientations to politics.40 The behavioural approach does not ignore the subjective aspects of political actions, although it subjects them to observation and quantification.

Focus on both formal institutions and informal political processes

It is also not true that the behavioural approach ignores formal political structures completely. It may be that the emphasis on inputs like pressure, demands and supports is greater than on outputs like decisions and policies. However, the systems analysis and conversion processes of the political system do take into account both formal and informal political structures. For example, Almond and Powell have made a six-fold classification of functions in terms of inputs—interest articulation (pressure and interest groups), interest aggregation (political parties) and communication; and outputs—legislation, administration and adjudication. The three input functions are factors that impinge upon or precede the three output functions.41 This provides a chance to study both formal and informal structures. This also explains why the three output institutions (legislature, executive and judiciary) function differently in different political systems. The parliamentary system works differently in Britain and India because informal processes (for example, caste in India) influence the two political systems differently.

Inter-disciplinary approach

The charge that the behavioural approach by focusing too much on other social sciences tends to compromise the boundary of political science is not valid. After all, politics should not be viewed independently of social factors and influences. Political sociology, for example, has helped in the understanding of the context in which institutions and formal political organs work. Again, to understand how caste (sociology) influences politics and electoral equations, or how the demand for minimum support price and subsidized electricity (economics), etc. by farmers influences politics, or how the emphasis on religious identity (psychology) shapes nationalism, we must turn to different disciplines of social sciences.

Revolt against traditional methods of political science

A comparison of traditional and behavioural approaches will make the distinction between their approaches, methods, focus, scope and subject matter clear.

- First, while traditional political enquiry is heavily inclined towards value theory, behavioural enquiry seeks causal theory. The focus in traditional enquiry is on normative principles; behavioural approach insists on logical assumptions and factual statements.

- Second, the focus in traditional studies is on description, while the behavioural approach seeks explanation and analysis.

- Third, the traditional approach generally applies deductive methods in which one moves from the general to the particular; hence it is speculative. The behavioural approach uses the inductive approach in which one moves from the particular to the general.

- Fourth, traditional political science is concerned more with institutions and legal concepts, while in the behavioural approach political processes constitute the main analytical framework.

- Fifth, in traditional political enquiry, the political arena is treated as separate. The behavioural approach seeks an integrated understanding of politics and political behaviour.

- Sixth, traditional political science is based on enquiry into Western political values (Greek, Roman and post-Renaissance Europe), while behavioural approach has opened the scope for enquiry in developing societies also.

- Seventh, the behavioural approach is inter-disciplinary and is based on scientific and analytical methods, whereas the traditional approach is value-based and even speculative.

These differences show that the behavioural approach is really a revolt against traditional political enquiry. The eight intellectual foundation stones listed by Easton are proof of this revolt.

Search for stable units of analysis

According to Easton the ‘… behavioural aspects of the new movement in political research involve more than method and reflect the inception of a theoretical search for stable units for understanding behaviour in its political aspects’. The behavioural approach is based on the conviction that there are certain fundamental units of analysis relating to human behaviour from which generalizations can be formed. These generalizations may provide a common base on which a specialized science of human beings could be built. The search for stable units of analysis and a common base is a part of the search for the unification (basis unity) of the social sciences. To bring unity among the social sciences, there can be no better way than to find certain ‘units’ of analysis, which can be applied alike to economics or politics or psychology or sociology. Common or stable units of analysis may be understood as repetitive, universally present and uniform, that is the smallest element of human behaviour that reflects through different institutions, structures and processes. For example, role as a unit can be applied to analyse political behaviour, social behaviour or psychological behaviour. Similarly, action, choice, decision, power, political socialization, etc. are some other units of analysis that have been proposed for analysing human behaviour. These units can also be applied in studying group behaviour. For example, the role of groups in politics was a popular theme of political study in the 1940s and 1950s.42 The search for stable units of analysis is not limited to the individual and group levels alone. Easton's systems analysis43 encompasses the political, social and economic environment as the focus of study. System as a unit of analysis covers society as a whole. Political scientists like Almond, Powell and others have applied political culture as a unit of analysis for society. The structural–functional analysis also provides units for analysing which structure in society performs which function.

Unit of analysis can be located at the process level also. Decision-making (Snyder) and communication (Deutsch) provide two important units representing the analysis of process—how decisions are made and what is the volume and flow of information and its content, etc. Thus, the behavioural approach seeks units of analysis at the individual and group levels, at the level of society and at the process level. Corresponding to the unit of analysis, conceptual frames of reference have also been developed (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Unit of Analysis and Conceptual Frames in Behavioural Approach

| Level of Units | Units of Analysis | Conceptual Frames |

|---|---|---|

| Individual/Group level | Role, action, choice, decision, power, socialization | Action theory, decision-making theory, power analysis |

| Society level | System, political culture, structures and functions | Systems analysis, structural–functional analysis |

| Process level | Decision-making, communication | Decision-making theory, communication theory |

Revolution in methods and techniques of political enquiry

If causal theory, or theory based on the cause–effect relationship, and not value theory is the aim of the behavioural approach, its method and techniques must provide for the collection of data, and its verification and analysis, so that empirically verifiable propositions can be made.

Towards this end, scientific techniques and methods of data collection, verification and analysis have been the major focus of the behavioural approach. In the early twentieth century and before the Second World War, the focus was on quantitative data, content analysis, statistical tables, psychoanalysis, etc. This period witnessed the use of empirical and quantitative methods to shift away from description-based political studies. However, these methods were used to enable more precise description and analysis,44 rather than achieve scientific theory-building. Lasswell's use of content analysis and psychoanalytical theory was the main achievement in this period.

After the Second World War, a host of political scientists such as Almond (structural–functional), Dahl (power), Easton (systems), Lasswell (power, content analysis), Deutsch (communication) and others sought to develop research designs and theoretical models to build empirical theories. This focus on empirical theory-building led to the development of sophisticated tools and techniques of research.

The revolution in methods and techniques has been in terms of data-gathering and research; analysis; and propositions or empirical theory or conceptual frame of reference. While the first two deal with techniques and tools, the third relates to theory-building. Let us take the first two in this section. The following tools and techniques for data collection and analysis are important in behavioural approach:

- Content analysis: the method of content analysis implies making an analysis of the contents of documents, papers, etc. on a subject matter, to gather data, evidence, trends, patterns, etc. for making generalizations or statements. Harold Lasswell and others popularized the use of content analysis as a tool of data- and evidence-gathering. However, Lasswell's study of propaganda in the First World War applying content analysis as a tool (Propaganda Technique in the Word War, 1938) was more qualitative than quantitative in nature. Content analysis subsequently became more sophisticated and shifted from qualitative to quantitative aspects in the works of Robert North (content analysis to detect trends in decision-makers’ perception of hostility and frustration) and Richart L. Merrit (content analysis of symbols of American community). There has also been content analysis of symbols of internationalism, democracy and other such ideas.45

- Case analysis: This refers to in-depth study of a case in order to gather data and information in a holistic manner. It helps in point-by-point comparison between two cases. Systematic case analysis for data-gathering is an important tool used in the behavioural approach.

- Sample survey: One sampling is aimed at identifying a group of units/elements/population that are representative of their respective universe or the whole to which they belong. Based on probability, it is expected that representative units (the sample) will give the same result as would be the case if the entire universe or population were to be studied or surveyed. For example, a sample survey of voters in the form of an exit poll can be used to predict election results.

- Interview/panel technique: While interview as a technique of evidence and data collection is used in many disciplines and pre-dates the behavioural approach, it has come to acquire a new direction and sophistication in the behavioural approach. Interview can be open-ended or closed-ended. In an open-ended interview, one can supplement whatever options are given as answers. In a closed-ended interview, most of the answers are of the YES/NO type or have fixed options. A special interview technique called panel technique is used to detect change or persistence in behaviour, preferences, attitudes, etc. of a sample of politically relevant persons, groups or community (the panel) through interviews at intervals over a period of time. For example, to assess the acceptability of a rural development programme by its beneficiaries, one can interview a sample of the beneficiaries before the policy is implemented and then once or twice again after it has been in operation for, say, two and four years on the basis of the same set of questions. After analysing the attitudes, preferences and acceptability levels at said intervals, one can conclude the effectiveness of the policy and its acceptability or otherwise by the people. Psephologists also use this technique to determine the shift or persistence in party and voting preferences.

- Depth and focused interview: Depth and focused interview is used to explore the personal, subjective and motivational aspects of people. The idea is to explore not only what one observes from the external behaviour of a person or agent but to go deeper and find out the meaning of that behaviour as understood by the actor. This is what Max Weber called the verstehen method, or the ‘interpretative understanding of action’. For example, a couple sitting in seclusion near a lit candle can be thought to be worshiping, celebrating their wedding anniversary, mourning the death of their son/daughter, or simply having a romantic moment. Any one of these interpretations is possible. To know for sure, one needs to know what meaning the couple attaches to the lit candle. It is said that in understanding human behaviour one can fruitfully utilize the method of interpretative understanding/verstehen. While in the verstehen method one seeks to put oneself in an actor's position subjectively, in in-depth interview the subjective meaning is taken from the actor himself/herself; the researcher's value preferences are excluded.

- Questionnaire: A questionnaire serves as a means to elicit information on a predetermined set of questions/issues. While in a normal interview, face-to-face interaction is possible and supplementary questions arising out of the interaction can be asked, in a questionnaire responses can only be collected on the basis of structured questions. The advantage of a questionnaire is that it does not allow the researcher to prompt or influence the respondent's answers.

- Participative observation: In anthropology and sociology, the method of participative observation is used, where the researcher without disclosing his/her identity becomes part of the community or group that is under observation. Participative observation has been used by anthropologists to understand the behaviour and meaning of actions, particularly in aboriginal communities.

- Multivariate analysis: The study of the relationship between multiple variables and their cause and effect helps to test the entire conceptual framework of reference or model at a time. Generally, a model or a conceptual framework of reference includes many concepts and variables. For example, in the systems model, demands and supports as inputs; decision-making as process of conversion, and policies and resource allocation as outputs are the different variables that require testing. This is possible only by multivariate analysis.

- Causal modelling and paired comparison: By means of causal modelling, the path of what causes what in the presence of multiple variables can be tested.46 For example, to understand the relationship among legislative process, party system, electoral behaviour and other informal processes, one needs to know what effect each one has on the other. Paired comparison is a technique of analysis where pairs of variables are analysed to find out variations arising out of shift in variables.

- Simulation: This is a technique to create a situation/environment like the original one with all its features, elements and parameters so as to study it in a controlled manner. With the aid of computer-based technologies, researchers can reproduce features of an environment that they want to study and make predictions or generalizations. Psychologists use this technique to predict voting behaviour.

Other techniques such as frequency distribution (distribution of periodic occurrence of a phenomenon in time or space) and scalogram analysis (test of attitudes or opinions in which the questions are ranked so that the answer to one implies the same answer to all questions lower on the scale)47 are also used.

The conclusion seems to be, according to Easton that, ‘the behavioural approach testifies to the coming of age of theory in social sciences as a whole, wedded, however, to a commitment to the assumptions and methods of empirical sciences’.

But do these refined and sophisticated techniques help in theory-building? And is it true that ‘the emergence of a behavioural approach goes beyond a methodological or mere technical orientation?’ What are the achievements of the behavioural approach in the field of theory-building?48

According to Easton, the ultimate objective of behavioural political science is to create a systematic theory, or causal theory, which helps to organize data into a patterned whole based on the functional relationship between facts and variables. As mentioned earlier, though behaviouralists generally aim to discover general laws of political behaviour and formulate overarching theories as their final goal, they start with low-level or middle-range theories. They claim that through systematization as one of the foundation stones of the behavioural approach, research and theory are integrally related: ‘Research untutored by theory, may prove to be trivial and theory unsupported by data, futile.’ With this perspective, theory-building, conceptual frames of reference and models are attempted by behaviouralists to impart meaning to findings. This is also reflected in the search for stable units of analysis to understand behaviour across disciplines in the social sciences.

Although these attempts can be treated as achievements of the behavioural approach in theory-building, it is generally accepted that the behavioural approach has shown its strength in research in individual, face-to-face or small group relationships. For example, it has been useful in explaining voting behaviour. But it fails to adequately explain relationships between institutions, such as between party system and legislature. Behavioural attempt at theory-building is more analytical than substantive, more general than particular, and more explanatory than descriptive and ethical. Despite its attempts, behavioural approach has not been able to formulate theory that can portray validated causal relationships or go beyond low-level conceptual frames and models.

In the aftermath of the debate between traditionalists and behaviouralists that occurred in the 1950s, a split among the behaviouralists themselves developed in the 1960s—between theoretical behaviouralists who insisted on theory-building irrespective of findings and research, and positive behaviouralists who insisted on research more than theory-building and even seemed to neglect political science. This debate set the stage for post-behaviouralism.

Elements of Behavioural Analysis in Kautilya, Machiavelli and Hobbes

We may mention here that the history of political thought within the traditional fold also contains elements of behavioural analysis. Kautilya, Machiavelli, Hobbes and Bentham have contributed in this direction. Jeremy Bentham's utilitarian creed of pain and pleasure, for example, drives from human nature. Kautilya's Arthashastra presents a very pragmatic view of statecraft and administration. His analysis of danda, or coercive authority, is exemplary in that he presents power as the essence of statecraft. Danda is the means by which the king ensures the protection of his subjects and prevents matsyanyaya (big fish eating small fish), a situation of anarchy. The importance of danda or coercive authority in Kautilya's analysis is so important that he refers to the art of politics as dandaniti, or the discipline of the policy of coercive authority. By analysing power, Kautilya makes power a unit of analysis in political study. Though his Arthashastra is not a treatise on politics, it presents almost an inter-disciplinary approach in understanding the affairs of statecraft.

Machiavelli's The Prince is a treatise that presents power as the essence of politics. He shows that human beings are driven by self-interest. Power as the ability to control others by compelling their obedience becomes an essential unit of political analysis in The Prince. The Prince, in essence is a ‘manual on the logic of acquiring and maintaining political power’.49 Further, Machiavelli's insistence on the possession and maintenance of power by the king is also a rejection of values and ethical concerns. His analysis of power as an objective criteria of understanding political behaviour and his insistence on what Sabine calls, ‘moral indifference’50 to the use of power has behavioural elements.

Like Machiavelli, Hobbes too presents an analysis of power and makes his analysis a ‘comprehensive science of power’. Following from the human psychology of fear and desire as the basis of understanding human behaviour, Hobbes constructs his political society. He adopts a scientific method based on body and motion. His theory of human nature or human psychology follows a scientific method. He differentiates between vital or involuntary motion, by which are meant basic life functions such as inhalation, digestion, circulation etc. and voluntary motion that are forms of human activity that are willed, such as walking, speaking, etc. Hobbes includes politics and various kinds of social interaction in voluntary motion. It is clear that Hobbes's voluntary motion stands for what is called behaviour by social scientists.51 Hobbes, by making voluntary motion the subject matter of political science, necessarily seeks to start from its psychological aspects. He evolves a theory of motion that triggers human voluntary activity. From here emerges the concept of the desire to attain pleasure and avoid pain. And this desire finally leads to ‘perpetual and restless desire of power after power. This method of scientifically establishing power as the basis of human behaviour is Hobbes's contribution to the behavioural aspect of political science. From this, Hobbes formulates his theory of social contract, powerful State and sovereignty.

Post-behaviouralism

The behavioural approach came under criticism by many political theorists for neglecting theory-building and even political science. Political philosophers such as Strauss argued that the behavioural approach was symptomatic of the crisis in political theory because it neglected normative issues. By the late 1960s, a Caucus for New Political Science developed within the America Political Science Association (APSA), which sought to reverse the identification of political science as a behavioural science. Given the social and political upheavals that were prevalent in America in the 1960s (civil rights movement, Cold War crisis, nuclear threat, feminist movement, impending Vietnam crisis), a new intellectual direction was emerging. The objectives and aims of the Caucus, as stated in their April 1969 manifesto, was to restore political science as a relevant and problem-solving discipline ‘which can serve the poor, oppressed and underdeveloped peoples at home and abroad in their struggles against the established hierarchies, elites and institutional forms of manipulation’.52 In 1969, David Easton, in his presidential address to the APSA, called this intellectual orientation the dawn of a ‘post-behavioural revolution’.53

Post-behaviouralism stands for a set of principles and intellectual direction, which includes relevant, purposive and value-laden research, and change- and action-oriented political enquiry, and demands that political scientists be critical intellectuals and guardian of human values instead of being mere methodologists. David Easton who had propounded the intellectual foundation stones of behaviouralism, now set forth seven major traits or features of post-behaviouralism, which he called ‘Credo of Relevance’.54

‘Credo of Relevance’: David Easton55

Substance over technique

The primacy of substance and purposive research is emphasized over mere techniques. We may recall the charge made against behaviouralism that for the sake of applying sophisticated tools of research it chose only those areas of research that were amenable to these tools. This way many areas of political enquiry suffered. Post-behaviouralism reverses the behaviouralist slogan, it is better to be wrong than vague, and declares that it is better to be vague than non-relevantly precise.

Change orientation

Behaviouralism was charged with being an ‘ideology of social conservatism tempered by modest incremental change’. Post-behaviouralism advocates change orientation and reform over preservation.

Relevant research