CHAPTER 1

Key Concepts of Supply Chain Management

After reading this chapter you will be able to

- Appreciate what a supply chain is and what it does

- Understand where your company fits in the supply chains it participates in and the role it plays in those supply chains

- Discuss ways to align your supply chain with your business strategy

- Start an intelligent conversation about the supply chain management issues in your company

This book is organized to give you a solid grounding in the “nuts and bolts” of supply chain management. The book explains the essential concepts and practices and then shows examples of how to put them to use. When you finish you will have a solid foundation in supply chain management to work from.

The first three chapters give you a working understanding of the key principles and business operations that drive any supply chain. The next four chapters present the techniques, technologies, and metrics to use to improve your internal operations and coordinate more effectively with your customers and suppliers in the supply chains your company is a part of. Chapter 7 presents specific ideas for using technologies such as social media and real-time simulation gaming to promote supply chain collaboration.

The last three chapters show you how to find supply chain opportunities and respond effectively to best capitalize on these opportunities. Case studies are used to illustrate supply chain challenges and to present solutions for those challenges. These case studies and their solutions bring together the material presented in the rest of the book and show how it applies to real-world business situations.

Supply chains encompass the companies and the business activities needed to design, make, deliver, and use a product or service. Businesses depend on their supply chains to provide them with what they need to survive and thrive. Every business fits into one or more supply chains and has a role to play in each of them.

The pace of change and the uncertainty about how markets will evolve has made it increasingly important for companies to be aware of the supply chains they participate in and to understand the roles that they play. Those companies that learn how to build and participate in strong supply chains will have a substantial competitive advantage in their markets.

Nothing Entirely New…Just a Significant Evolution

The practice of supply chain management is guided by some basic underlying concepts that have not changed much over the centuries. Several hundred years ago, Napoleon made the remark, “An army marches on its stomach.” Napoleon was a master strategist and a skillful general and this remark shows that he clearly understood the importance of what we would now call an efficient supply chain. Unless the soldiers are fed, the army cannot move.

Along these same lines, there is another saying that goes, “Amateurs talk strategy and professionals talk logistics.” People can discuss all sorts of grand strategies and dashing maneuvers but none of that will be possible without first figuring out how to meet the day-to-day demands of providing an army with fuel, spare parts, food, shelter, and ammunition. It is the seemingly mundane activities of the quartermaster and the supply sergeants that often determine an army's success. This has many analogies in business.

The term “supply chain management” arose in the late 1980s and came into widespread use in the 1990s. Prior to that time, businesses used terms such as “logistics” and “operations management” instead. Here are some definitions of a supply chain:

- “A supply chain is the alignment of firms that bring products or services to market.”—from Lambert, Stock, and Ellram. (Lambert, Douglas M., James R. Stock, and Lisa M. Ellram, 1998, Fundamentals of Logistics Management, Boston, MA: Irwin/McGraw-Hill, Chapter 14).

- “A supply chain consists of all stages involved, directly or indirectly, in fulfilling a customer request. The supply chain not only includes the manufacturer and suppliers, but also transporters, warehouses, retailers, and customers themselves.”—from Chopra and Meindl (Chopra, Sunil, and Peter Meindl, 2003, Supply Chain, Second Edition, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., Chapter 1).

- “A supply chain is a network of facilities and distribution options that performs the functions of procurement of materials, transformation of these materials into intermediate and finished products, and the distribution of these finished products to customers.”—from Ganeshan and Harrison (Ganeshan, Ram, and Terry P. Harrison, 1995, “An Introduction to Supply Chain Management,” Department of Management Sciences and Information Systems, 303 Beam Business Building, Penn State University, University Park, Pennsylvania).

If this is what a supply chain is then we can define supply chain management as the things we do to influence the behavior of the supply chain and get the results we want. Some definitions of supply chain management are:

- “The systemic, strategic coordination of the traditional business functions and the tactics across these business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole.”—from Mentzer, DeWitt, Keebler, Min, Nix, Smith, and Zacharia (Mentzer, John T., William DeWitt, James S. Keebler, Soonhong Min, Nancy W. Nix, Carlo D. Smith, and Zach G. Zacharia, 2001, “Defining Supply Chain Management,” Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 22, No. 2, p. 18).

- “Supply chain management is the coordination of production, inventory, location, and transportation among the participants in a supply chain to achieve the best mix of responsiveness and efficiency for the market being served.”—my own words.

There is a difference between the concept of supply chain management and the traditional concept of logistics. Logistics typically refers to activities that occur within the boundaries of a single organization and supply chains refer to networks of companies that work together and coordinate their actions to deliver a product to market. Also, traditional logistics focuses its attention on activities such as procurement, distribution, maintenance, and inventory management. Supply chain management acknowledges all of traditional logistics and also includes activities such as marketing, new product development, finance, and customer service.

In the wider view of supply chain thinking, these additional activities are now seen as part of the work needed to fulfill customer requests. Supply chain management views the supply chain and the organizations in it as a single entity. It brings a systems approach to understanding and managing the different activities needed to coordinate the flow of products and services to best serve the ultimate customer. This systems approach provides the framework in which to best respond to business requirements that otherwise would seem to be in conflict with each other.

Taken individually, different supply chain requirements often have conflicting needs. For instance, the requirement of maintaining high levels of customer service calls for maintaining high levels of inventory, but then the requirement to operate efficiently calls for reducing inventory levels. It is only when these requirements are seen together as parts of a larger picture that ways can be found to effectively balance their different demands.

Effective supply chain management requires simultaneous improvements in both customer service levels and the internal operating efficiencies of the companies in the supply chain. Customer service at its most basic level means consistently high order-fill rates, high on-time delivery rates, and a very low rate of products returned by customers for whatever reason. Internal efficiency for organizations in a supply chain means that these organizations get an attractive rate of return on their investments in inventory and other assets and that they find ways to lower their operating and sales expenses.

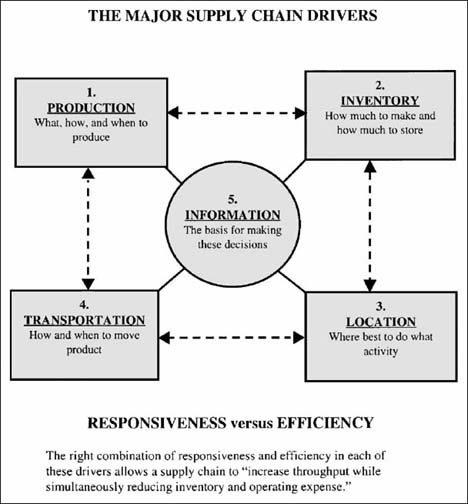

There is a basic pattern to the practice of supply chain management. Each supply chain has its own unique set of market demands and operating challenges and yet the issues remain essentially the same in every case. Companies in any supply chain must make decisions individually and collectively regarding their actions in five areas:

- Production—What products does the market want? How much of which products should be produced and by when? This activity includes the creation of master production schedules that take into account plant capacities, workload balancing, quality control, and equipment maintenance.

- Inventory—What inventory should be stocked at each stage in a supply chain? How much inventory should be held as raw materials, semifinished, or finished goods? The primary purpose of inventory is to act as a buffer against uncertainty in the supply chain. However, holding inventory can be expensive, so what are the optimal inventory levels and reorder points?

- Location—Where should facilities for production and inventory storage be located? Where are the most cost efficient locations for production and for storage of inventory? Should existing facilities be used or new ones built? Once these decisions are made they determine the possible paths available for product to flow through for delivery to the final consumer.

- Transportation—How should inventory be moved from one supply chain location to another? Air-freight and truck delivery are generally fast and reliable but they are expensive. Shipping by sea or rail is much less expensive but usually involves longer transit times and more uncertainty. This uncertainty must be compensated for by stocking higher levels of inventory. When is it better to use which mode of transportation?

- Information—How much data should be collected and how much information should be shared? Timely and accurate information holds the promise of better coordination and better decision making. With good information, people can make effective decisions about what to produce and how much, about where to locate inventory, and how best to transport it.

The sum of these decisions will define the capabilities and effectiveness of a company's supply chain. The things a company can do and the ways that it can compete in its markets are all very much dependent on the effectiveness of its supply chain. If a company's strategy is to serve a mass market and compete on the basis of price, it had better have a supply chain that is optimized for low cost. If a company's strategy is to serve a market segment and compete on the basis of customer service and convenience, it had better have a supply chain optimized for responsiveness. Who a company is and what it can do is shaped by its supply chain and by the markets it serves.

How the Supply Chain Works

Two influential source books that define principles and practices of supply chain management are The Goal (Goldratt, Eliyahu M., 1984, The Goal, Great Barrington, MA: The North River Press Publishing Corporation); and Supply Chain Management, Fourth Edition by Sunil Chopra and Peter Meindl. The Goal explores the issues and provides answers to the problem of optimizing operations in any business system, whether it be manufacturing, mortgage loan processing, or supply chain management. Supply Chain Management, Fourth Edition is an in-depth presentation of the concepts and techniques of the profession. Much of the material presented in this chapter and in the next two chapters can be found in greater detail in these two books.

IN THE REAL WORLD

Alexander the Great based his strategies and campaigns on his army's unique capabilities and these were made possible by effective supply chain management.

In the spirit of the saying, “Amateurs talk strategy and professionals talk logistics,” let's look at the campaigns of Alexander the Great. For those who think that his greatness was only due to his ability to dream up bold moves and cut a dashing figure in the saddle, think again. Alexander was a master of supply chain management and he could not have succeeded otherwise. The authors from Greek and Roman times who recorded his deeds had little to say about something so apparently unglamorous as how he secured supplies for his army. Yet, from these same sources, many small details can be pieced together to show the overall supply chain picture and how Alexander managed it. A modern historian, Donald Engels, has investigated this topic in his book Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army (Engles, Donald W., 1978, Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army, Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press).

He begins by pointing out that given the conditions and the technology that existed in Alexander's time, his strategy and tactics had to be very closely tied to his ability to get supplies and to run a lean, efficient organization. The only way to transport large amounts of material over long distances was by oceangoing ships or by barges on rivers and canals. Once away from rivers and seacoasts, an army had to be able to live off the land over which it traveled. Diminishing returns set in quickly when using pack animals and carts to haul supplies, because the animals themselves had to eat and would soon consume all the food and water they were hauling unless they could graze along the way.

Alexander's army was able to achieve its brilliant successes because it managed its supply chain so well. The army had a logistics structure that was fundamentally different from other armies of the time. In other armies the number of support people and camp followers was often as large as the number of actual fighting soldiers, because armies traveled with huge numbers of carts and pack animals to carry their equipment and provisions, as well as the people needed to tend them. In the Macedonian army the use of carts was severely restricted. Soldiers were trained to carry their own equipment and provisions. Other contemporary armies did not require their soldiers to carry such heavy burdens but they paid for this because the resulting baggage trains reduced their speed and mobility. The result of the Macedonian army's logistics structure was that it became the fastest, lightest, and most mobile army of its time. It was capable of making lightning strikes against an opponent, often before they were even aware of what was happening. Because the army was able to move quickly and suddenly, Alexander could use this capability to devise strategies and employ tactics that allowed him to surprise and overwhelm enemies that were numerically much larger.

The picture that emerges of how Alexander managed his supply chain is an interesting one. For instance, time and again the historical sources mention that before he entered a new territory, he would receive the surrender of its ruler and arrange in advance with local officials for the supplies his army would need. If a region did not surrender to him in advance, Alexander would not commit his entire army to a campaign in that land. He would not risk putting his army in a situation where it could be crippled or destroyed by a lack of provisions. Instead, he would gather intelligence about the routes, the resources, and the climate of the region and then set off with a small, light force to surprise his opponent. The main army would remain behind at a well-stocked base until Alexander secured adequate supplies for it to follow.

Whenever the army set up a new base it looked for an area that provided easy access to a navigable river or a seaport. Then ships would arrive from other parts of Alexander's empire, bringing in large amounts of supplies. The army always stayed in its winter camp until the first spring harvest of the new year so that food supplies would be available. When it marched, it avoided dry or uninhabited areas and moved through river valleys and populated regions whenever possible so the horses could graze and the army could requisition supplies along the route.

Alexander had a deep understanding of the capabilities and limitations of his supply chain. He learned well how to formulate strategies and use tactics that built upon the unique strengths that his logistics and supply chain capabilities gave him, and he wisely took measures to compensate for the limitations of his supply chain. His opponents often outnumbered him and were usually fighting on their own home territory. Yet their advantages were undermined by clumsy and inefficient supply chains that restricted their ability to act and limited their options for opposing Alexander's moves.

The goal or mission of supply chain management can be defined using Eli Goldratt's words as “Increase throughput while simultaneously reducing both inventory and operating expense.” In this definition, throughput refers to the rate at which sales to the end customer occur. Depending on the market being served, sales or throughput occur for different reasons. In some markets, customers value and will pay for high levels of service. In other markets customers seek simply the lowest price for an item.

As we saw in the previous section, there are five areas where companies can make decisions that will define their supply chain capabilities: production; inventory; location; transportation; and information. Chopra and Meindl define the first four and I add the fifth as performance drivers that can be managed to produce the capabilities needed for a given supply chain.

Effective supply chain management calls first for an understanding of each driver and how it operates. Each driver has the ability to directly affect the supply chain and enable certain capabilities. The next step is to develop an appreciation for the results that can be obtained by mixing different combinations of these drivers. Let's start by looking at the drivers individually.

Production

Production refers to the capacity of a supply chain to make and store products. The facilities of production are factories and warehouses. The fundamental decision that managers face when making production decisions is how to resolve the trade-off between responsiveness and efficiency. If factories and warehouses are built with a lot of excess capacity, they can be very flexible and respond quickly to wide swings in product demand. Facilities where all or almost all capacity is being used are not capable of responding easily to fluctuations in demand. On the other hand, capacity costs money and excess capacity is idle capacity not in use and not generating revenue. So the more excess capacity that exists, the less efficient the operation becomes.

Factories can be built to accommodate one of two approaches to manufacturing:

- Product Focus—A factory that takes a product focus performs the range of different operations required to make a given product line from fabrication of different product parts to assembly of these parts.

- Functional Focus—A functional approach concentrates on performing just a few operations such as only making a select group of parts or only doing assembly. These functions can be applied to making many different kinds of products.

A product approach tends to result in developing expertise about a given set of products at the expense of expertise about any particular function. A functional approach results in expertise about particular functions instead of expertise in a given product. Companies need to decide which approach or what mix of these two approaches will give them the capability and expertise they need to best respond to customer demands.

As with factories, warehouses too can be built to accommodate different approaches. There are three main approaches to use in warehousing:

- Stock Keeping Unit (SKU) Storage—In this traditional approach, all of a given type of product is stored together. This is an efficient and easy to understand way to store products.

- Job Lot Storage—In this approach, all the different products related to the needs of a certain type of customer or related to the needs of a particular job are stored together. This allows for an efficient picking and packing operation but usually requires more storage space than the traditional SKU storage approach.

- Crossdocking—An approach that was pioneered by Wal-Mart in its drive to increase efficiencies in its supply chain. In this approach, product is not actually warehoused in the facility. Instead the facility is used to house a process where trucks from suppliers arrive and unload large quantities of different products. These large lots are then broken down into smaller lots. Smaller lots of different products are recombined according to the needs of the day and quickly loaded onto outbound trucks that deliver the products to their final destinations.

Inventory

Inventory is spread throughout the supply chain and includes everything from raw material to work in process to finished goods that are held by the manufacturers, distributors, and retailers in a supply chain. Again, managers must decide where they want to position themselves in the trade-off between responsiveness and efficiency. Holding large amounts of inventory allows a company or an entire supply chain to be very responsive to fluctuations in customer demand. However, the creation and storage of inventory is a cost and to achieve high levels of efficiency, the cost of inventory should be kept as low as possible.

There are three basic decisions to make regarding the creation and holding of inventory:

- Cycle Inventory—This is the amount of inventory needed to satisfy demand for the product in the period between purchases of the product. Companies tend to produce and to purchase in large lots in order to gain the advantages that economies of scale can bring. However, with large lots also come increased carrying costs. Carrying costs come from the cost to store, handle, and insure the inventory. Managers face the tradeoff between the reduced cost of ordering and better prices offered by purchasing product in large lots and the increased carrying cost of the cycle inventory that comes with purchasing in large lots.

- Safety Inventory—Inventory that is held as a buffer against uncertainty. If demand forecasting could be done with perfect accuracy, then the only inventory that would be needed would be cycle inventory. But since every forecast has some degree of uncertainty in it, we cover that uncertainty to a greater or lesser degree by holding additional inventory in case demand is suddenly greater than anticipated. The tradeoff here is to weigh the costs of carrying extra inventory against the costs of losing sales due to insufficient inventory.

- Seasonal Inventory—This is inventory that is built up in anticipation of predictable increases in demand that occur at certain times of the year. For example, it is predictable that demand for antifreeze will increase in the winter. If a company that makes antifreeze has a fixed production rate that is expensive to change, then it will try to manufacture product at a steady rate all year long and build up inventory during periods of low demand to cover for periods of high demand that will exceed its production rate. The alternative to building up seasonal inventory is to invest in flexible manufacturing facilities that can quickly change their rates of production of different products to respond to increases in demand. In this case, the tradeoff is between the cost of carrying seasonal inventory and the cost of having more flexible production capabilities.

Location

Location refers to the geographical site of supply chain facilities. It also includes the decisions related to which activities should be performed in each facility. The responsiveness versus efficiency tradeoff here is the decision whether to centralize activities in fewer locations to gain economies of scale and efficiency, or to decentralize activities in many locations close to customers and suppliers in order for operations to be more responsive.

When making location decisions, managers need to consider a range of factors that relate to a given location including the cost of facilities, the cost of labor, skills available in the workforce, infrastructure conditions, taxes and tariffs, and proximity to suppliers and customers. Location decisions tend to be very strategic decisions because they commit large amounts of money to long-term plans.

Location decisions have strong impacts on the cost and performance characteristics of a supply chain. Once the size, number, and location of facilities are determined, that also defines the number of possible paths through which products can flow on the way to the final customer. Location decisions reflect a company's basic strategy for building and delivering its products to market.

Transportation

This refers to the movement of everything from raw material to finished goods between different facilities in a supply chain. In transportation the tradeoff between responsiveness and efficiency is manifested in the choice of transport mode. Fast modes of transport such as airplanes are very responsive but also more costly. Slower modes such as ship and rail are very cost efficient but not as responsive. Since transportation costs can be as much as a third of the operating cost of a supply chain, decisions made here are very important.

There are six basic modes of transport that a company can choose from:

- Ship—which is very cost efficient but also the slowest mode of transport. It is limited to use between locations that are situated next to navigable waterways and facilities such as harbors and canals.

- Rail—which is also very cost efficient but can be slow. This mode is also restricted to use between locations that are served by rail lines.

- Pipelines—which can be very efficient but are restricted to commodities that are liquids or gases such as water, oil, and natural gas.

- Trucks—which are a relatively quick and very flexible mode of transport. Trucks can go almost anywhere. The cost of this mode is prone to fluctuations though, as the cost of fuel fluctuates and the condition of roads varies.

- Airplanes—which are a very fast mode of transport and are very responsive. This is also the most expensive mode, and it is somewhat limited by the availability of appropriate airport facilities.

- Electronic Transport—which is the fastest mode of transport and is very flexible and cost efficient. However, it can only be used for movement of certain types of products such as electric energy, data, and products composed of data such as music, pictures, and text. Someday technology that allows us to convert matter to energy and back to matter again may completely rewrite the theory and practice of supply chain management (“beam me up, Scotty…”).

Given these different modes of transportation and the location of the facilities in a supply chain, managers need to design routes and networks for moving products. A route is the path through which products move, and networks are composed of the collection of the paths and facilities connected by those paths. As a general rule, the higher the value of a product (such as electronic components or pharmaceuticals), the more its transport network should emphasize responsiveness, and the lower the value of a product (such as bulk commodities like grain or lumber), the more its network should emphasize efficiency.

Information

Information is the basis upon which to make decisions regarding the other four supply chain drivers. It is the connection between all of the activities and operations in a supply chain. To the extent that this connection is a strong one (i.e., the data is accurate, timely, and complete), the companies in a supply chain will each be able to make good decisions for their own operations. This will also tend to maximize the profitability of the supply chain as a whole. That is the way that stock markets or other free markets work and supply chains have many of the same dynamics as markets.

Information is used for two purposes in any supply chain:

- Coordinating daily activities related to the functioning of the other four supply chain drivers: production; inventory; location; and transportation. The companies in a supply chain use available data on product supply and demand to decide on weekly production schedules, inventory levels, transportation routes, and stocking locations.

- Forecasting and planning to anticipate and meet future demands. Available information is used to make tactical forecasts to guide the setting of monthly and quarterly production schedules and timetables. Information is also used for strategic forecasts to guide decisions about whether to build new facilities, enter a new market, or exit an existing market.

TIPS & TECHNIQUES

The Five Major Supply Chain Drivers

Each market or group of customers has a specific set of needs. The supply chains that serve different markets need to respond effectively to these needs. Some markets demand and will pay for high levels of responsiveness. Other markets require their supply chains to focus more on efficiency. The overall effect of the decisions made concerning each driver will determine how well the supply chain serves its market and how profitable it is for the participants in that supply chain.

Within an individual company the tradeoff between responsiveness and efficiency involves weighing the benefits that good information can provide against the cost of acquiring that information. Abundant, accurate information can enable very efficient operating decisions and better forecasts but the cost of building and installing systems to deliver this information can be very high.

Within the supply chain as a whole, the responsiveness versus efficiency tradeoff that companies make is one of deciding how much information to share with the other companies and how much information to keep private. The more information about product supply, customer demand, market forecasts, and production schedules that companies share with each other, the more responsive everyone can be. Balancing this openness however, are the concerns that each company has about revealing information that could be used against it by a competitor. The potential costs associated with increased competition can hurt the profitability of a company.

EXECUTIVE INSIGHT

Wal-Mart is a company shaped by its supply chain and the efficiency of its supply chain has made it a leader in the markets it serves.

Sam Walton decided to build a company that would serve a mass market and compete on the basis of price. He did this by creating one of the world's most efficient supply chains. The structure and operations of this company have been defined by the need to lower its costs and increase its productivity so that it could pass these savings on to its customers in the form of lower prices. The techniques that Wal-Mart pioneered are now being widely adopted by its competitors and by other companies serving entirely different markets.

Wal-Mart introduced concepts that are now industry standards. Many of these concepts come directly from the way the company builds and operates its supply chain. Let's look at four such concepts:

![]() The strategy of expanding around distribution centers (DCs)

The strategy of expanding around distribution centers (DCs)

![]() Using electronic data interchange (EDI) with suppliers

Using electronic data interchange (EDI) with suppliers

![]() The “big box” store format

The “big box” store format

![]() “Everyday low prices”

“Everyday low prices”

The strategy of expanding around DCs is central to the way Wal-Mart enters a new geographical market. The company looks for areas that can support a group of new stores, not just a single new store. It then builds a new DC at a central location in the area and opens its first store at the same time. The DC is the supply chain bridgehead into the new territory. It supports the opening of more new stores in the area at a very low additional cost. Those savings are passed along to the customers.

The use of EDI with suppliers provides the company two substantial benefits. First of all this cuts the transaction costs associated with the ordering of products and the paying of invoices. Ordering products and paying invoices are, for the most part, well-defined and routine processes that can be made very productive and efficient through EDI. The second benefit is that these electronic links with suppliers allow Wal-Mart a high degree of control and coordination in the scheduling and receiving of product deliveries. This helps to ensure a steady flow of the right products at the right time, delivered to the right DCs, by all Wal-Mart suppliers.

The “big box” store format allows Wal-Mart to, in effect, combine a store and a warehouse in a single facility and get great operating efficiencies from doing so. The big box is big enough to hold large amounts of inventory like a warehouse. And since this inventory is being held at the same location where the customer buys it, there is no delay or cost that would otherwise be associated with moving products from warehouse to store. Again, these savings are passed along to the customer. “Everyday low prices” are a way of doing two things. The first thing is to tell its price-conscious customers that they will always get the best price. They need not look elsewhere or wait for special sales. The effect of this message to customers helps Wal-Mart do the second thing, which is to accurately forecast product sales. By eliminating special sales and assuring customers of low prices, it smoothes out demand swings, making demand more steady and predictable. This way stores are more likely to have what customers want when they want it.

Taken individually, these four concepts are each useful but their real power comes from being used in connection with each other. They combine to form a supply chain that drives a self-reinforcing business process. Each concept builds on the strengths of the others to create a powerful business model for a company that has grown to become a dominant player in its markets.

There seem to be some similarities between Wal-Mart and Alexander the Great. Both developed very effective supply chains that were central to their success.

The Evolving Structure of Supply Chains

The participants in a supply chain are continuously making decisions that affect how they manage the five supply chain drivers. Each organization tries to maximize its performance in dealing with these drivers through a combination of outsourcing, partnering, and in-house expertise. In the fast-moving markets of our present economy, a company usually will focus on what it considers to be its core competencies in supply chain management and outsource the rest.

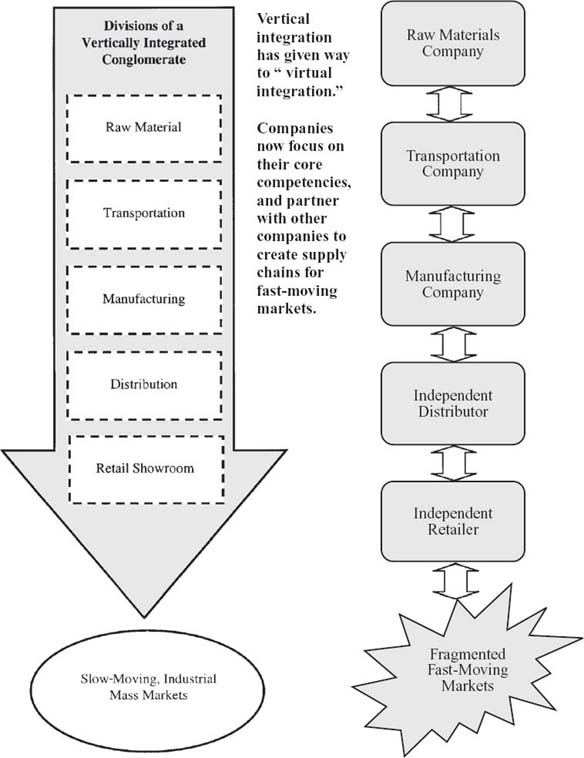

This was not always the case though. In the slower-moving mass markets of the industrial age it was common for successful companies to attempt to own much of their supply chain. That was known as vertical integration. The aim of vertical integration was to gain maximum efficiency through economies of scale (see Exhibit 1.1).

Old Supply Chains Versus New

Vertically integrated companies serving slow-moving mass markets once attempted to own much of their supply chains. Today's fast-moving markets require more flexible and responsive supply chains.

In the first half of the 1900s, Ford Motor Company owned much of what it needed to feed its car factories. It owned and operated iron mines that extracted iron ore, steel mills that turned the ore into steel products, plants that made component car parts, and assembly plants that turned out finished cars. In addition, they owned farms where they grew flax to make into linen car tops and forests that they logged and sawmills where they cut the timber into lumber for making wooden car parts. Ford's famous River Rouge Plant was a monument to vertical integration—iron ore went in at one end and cars came out at the other end. Henry Ford in his 1926 autobiography, Today and Tomorrow, boasted that his company could take in iron ore from the mine and put out a car 81 hours later (Ford, Henry, 1926, Today and Tomorrow, Portland, Oregon: Productivity Press, Inc.).

This was a profitable way of doing business in the more predictable, one-size-fits-all industrial economy that existed in the early 1900s. Ford and other businesses churned out mass amounts of basic products. But as the markets grew and customers became more particular about the kind of products they wanted, this model began to break down. It could not be responsive enough or produce the variety of products that were being demanded. For instance, when Henry Ford was asked about the number of different colors a customer could request, he said, “They can have any color they want as long as it's black.” In the 1920s Ford's market share was more than 50 percent, but by the 1940s it had fallen to below 20 percent. Focusing on efficiency at the expense of being responsive to customer desires was no longer a successful business model.

Globalization, highly competitive markets, and the rapid pace of technological change are now driving the development of supply chains where multiple companies work together, each company focusing on the activities that it does best. Mining companies focus on mining, timber companies focus on logging and making lumber, and manufacturing companies focus on different types of manufacturing from making component parts to doing final assembly. This way people in each company can keep up with rapid rates of change and keep learning the new skills needed to compete in their particular businesses.

Where companies once routinely ran their own warehouses or operated their own fleets of trucks, they now have to consider whether those operations are really a core competency or whether it is more cost effective to outsource those operations to other companies that make logistics the center of their business. To achieve high levels of operating efficiency and to keep up with continuing changes in technology, companies need to focus on their core competencies. It requires this kind of focus to stay competitive.

Instead of vertical integration, companies now practice “virtual integration.” Companies find other companies whom they can work with to perform the activities called for in their supply chains. How a company defines its core competencies and how it positions itself in the supply chains it serves is one of the most important decisions it can make.

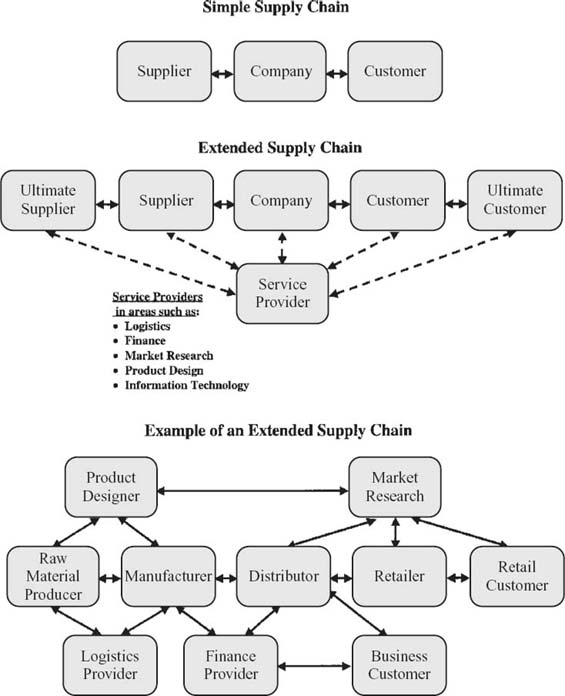

Participants in the Supply Chain

In its simplest form, a supply chain is composed of a company and the suppliers and customers of that company. This is the basic group of participants who create a simple supply chain. Extended supply chains contain three additional types of participants. First there is the supplier's supplier or the ultimate supplier at the beginning of an extended supply chain. Then there is the customer's customer or ultimate customer at the end of an extended supply chain. Finally there is a whole category of companies who are service providers to other companies in the supply chain. These are companies who supply services in logistics, finance, marketing, and information technology.

In any given supply chain there is some combination of companies who perform different functions. There are companies who are producers, distributors or wholesalers, retailers, and companies or individuals who are the customers, the final consumers of a product. Supporting these companies there will be other companies that are service providers that provide a range of needed services.

Producers

Producers or manufacturers are organizations that make a product. This includes companies that are producers of raw materials and companies that are producers of finished goods. Producers of raw materials are organizations that mine for minerals, drill for oil and gas, and cut timber. It also includes organizations that farm the land, raise animals, or catch seafood. Producers of finished goods use the raw materials and subassemblies made by other producers to create their products.

Producers can create products that are intangible items such as music, entertainment, software, or designs. A product can also be a service such as mowing a lawn, cleaning an office, performing surgery, or teaching a skill. In many instances the producers of tangible, industrial products are moving to areas of the world where labor is less costly. Producers in the developed world of North America, Europe, and parts of Asia are increasingly producers of intangible items and services.

Distributors

Distributors are companies that take inventory in bulk from producers and deliver a bundle of related product lines to customers. Distributors are also known as wholesalers. They typically sell to other businesses and they sell products in larger quantities than an individual consumer would usually buy. Distributors buffer the producers from fluctuations in product demand by stocking inventory and doing much of the sales work to find and service customers. For the customer, distributors fulfill the “Time and Place” function—they deliver products when and where the customer wants them.

A distributor is typically an organization that takes ownership of significant inventories of products that they buy from producers and sell to consumers. In addition to product promotion and sales, other functions the distributor performs are inventory management, warehouse operations, and product transportation, as well as customer support and post-sales service. A distributor can also be an organization that only brokers a product between the producer and the customer, and never takes ownership of that product. This kind of distributor performs mainly the functions of product promotion and sales. In both of these cases, as the needs of customers evolve and the range of available products changes, the distributor is the agent that continually tracks customer needs and matches them with products available.

Retailers

Retailers stock inventory and sell in smaller quantities to the general public. This organization also closely tracks the preferences and demands of the customers that it sells to. It advertises to its customers and often uses some combination of price, product selection, service, and convenience as the primary draw to attract customers for the products it sells. Discount department stores attract customers using price and wide product selection. Upscale specialty stores offer a unique line of products and high levels of service. Fast food restaurants use convenience and low prices as their draw.

Customers

Customers or consumers are any organization that purchases and uses a product. A customer organization may purchase a product in order to incorporate it into another product that they in turn sell to other customers. Or a customer may be the final end user of a product who buys the product in order to consume it.

Service Providers

These are organizations that provide services to producers, distributors, retailers, and customers. Service providers have developed special expertise and skills that focus on a particular activity needed by a supply chain. Because of this, they are able to perform these services more effectively and at a better price than producers, distributors, retailers, or consumers could do on their own.

Some common service providers in any supply chain are providers of transportation services and warehousing services. These are trucking companies and public warehouse companies and they are known as logistics providers. Financial service providers deliver services such as making loans, doing credit analysis, and collecting on past due invoices. These are banks, credit rating companies, and collection agencies. Some service providers deliver market research and advertising, while others provide product design, engineering services, legal services, and management advice. Still other service providers offer information technology and data collection services. All of these service providers are integrated to a greater or lesser degree into the ongoing operations of the producers, distributors, retailers, and consumers in the supply chain.

Supply chains are composed of repeating sets of participants that fall into one or more of these categories. Over time the needs of the supply chain as a whole remain fairly stable. What changes is the mix of participants in the supply chain and the roles that each participant plays. In some supply chains, there are few service providers because the other participants perform these services on their own. In other supply chains very efficient providers of specialized services have evolved and the other participants outsource work to these service providers instead of doing it themselves. Examples of supply chain structure are shown in Exhibit 1.2.

Supply Chain Structure

Aligning the Supply Chain with Business Strategy

A company's supply chain is an integral part of its approach to the markets it serves. The supply chain needs to respond to market requirements and do so in a way that supports the company's business strategy. The business strategy a company employs starts with the needs of the customers that the company serves or will serve. Depending on the needs of its customers, a company's supply chain must deliver the appropriate mix of responsiveness and efficiency. A company whose supply chain allows it to more efficiently meet the needs of its customers will gain market share at the expense of other companies in that market and also will be more profitable.

For example, let's consider two companies and the needs that their supply chains must respond to. The two companies are 7-Eleven and Sam's Club, which is a part of Wal-Mart. The customers who shop at convenience stores like 7-Eleven have a different set of needs and preferences from those who shop at a discount warehouse like Sam's Club. The 7-Eleven customer is looking for convenience and not the lowest price. That customer is often in a hurry, and prefers that the store be nearby and have enough variety of products so that they can pick up small amounts of common household or food items that they need immediately. Sam's Club customers are looking for the lowest price. They are not in a hurry and are willing to drive some distance and buy large quantities of limited numbers of items in order to get the lowest price possible.

Clearly the supply chain for 7-Eleven needs to emphasize responsiveness. That group of customers expects convenience and will pay for it. On the other hand, the Sam's Club supply chain needs to focus tightly on efficiency. The Sam's Club customer is very price conscious and the supply chain needs to find every opportunity to reduce costs so that these savings can be passed on to the customers. Both of these companies' supply chains are well aligned with their business strategies and because of this they are each successful in their markets.

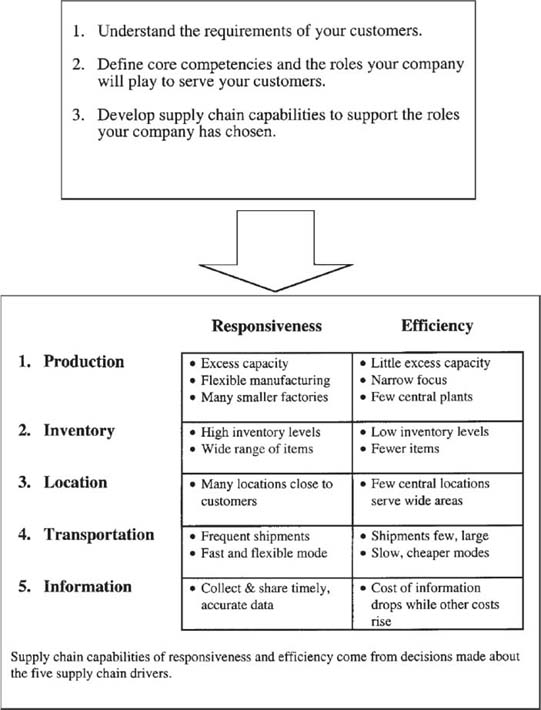

There are three steps to use in aligning your supply chain with your business strategy. The first step is to understand the markets that your company serves. The second step is to define the strengths or core competencies of your company and the role the company can or could play in serving its markets. The last step is to develop the needed supply chain capabilities to support the roles your company has chosen.

Understand the Markets Your Company Serves

Begin by asking questions about your customers. What kind of customer does your company serve? What kind of customer does your customer sell to? What kind of supply chain is your company a part of? The answers to these questions will tell you what supply chains your company serves and whether your supply chain needs to emphasize responsiveness or efficiency. Chopra and Meindl have defined the following attributes that help to clarify requirements for the customers you serve. These attributes are:

- The quantity of the product needed in each lot—Do your customers want small amounts of products or will they buy large quantities? A customer at a convenience store or a drug store buys in small quantities. A customer of a discount warehouse club, such as Sam's Club, buys in large quantities.

- The response time that customers are willing to tolerate—Do your customers buy on short notice and expect quick service or is a longer lead time acceptable? Customers of a fast food restaurant certainly buy on short notice and expect quick service. Customers buying custom machinery would plan the purchase in advance and expect some lead time before the product could be delivered.

- The variety of products needed—Are customers looking for a narrow and well-defined bundle of products or are they looking for a wide selection of different kinds of products? Customers of a fashion boutique expect a narrowly defined group of products. Customers of a “big box” discount store like Wal-Mart expect a wide variety of products to be available.

- The service level required—Do customers expect all products to be available for immediate delivery or will they accept partial deliveries of products and longer lead times? Customers of a music store expect to get the CD they are looking for immediately or they will go elsewhere. Customers who order a custom-built new machine tool expect to wait a while before delivery.

- The price of the product—How much are customers willing to pay? Some customers will pay more for convenience or high levels of service and other customers look to buy based on the lowest price they can get.

- The desired rate of innovation in the product—How fast are new products introduced and how long before existing products become obsolete? In products such as electronics and computers, customers expect a high rate of innovation. In other products, such as house paint, customers do not desire such a high rate of innovation.

Define Core Competencies of Your Company

The next step is to define the role that your company plays or wants to play in these supply chains. What kind of supply chain participant is your company? Is your company a producer, a distributor, a retailer, or a service provider? What does your company do to enable the supply chains that it is part of? What are the core competencies of your company? How does your company make money? The answers to these questions tell you what roles in a supply chain will be the best fit for your company.

Be aware that your company can serve multiple markets and participate in multiple supply chains. A company like W.W. Grainger serves several different markets. It sells maintenance, repair, and operating (MRO) supplies to large national account customers such as Ford and Boeing and it also sells these supplies to small businesses and building contractors. These two different markets have different requirements as measured by the above customer attributes.

When you are serving multiple market segments, your company will need to look for ways to leverage its core competencies. Parts of these supply chains may be unique to the market segment they serve, while other parts can be combined to achieve economies of scale. For example, if manufacturing is a core competency for a company, it can build a range of different products in common production facilities. Then different inventory and transportation options can be used to deliver the products to customers in different market segments.

Develop Needed Supply Chain Capabilities

Once you know what kind of markets your company serves and the role your company does or will play in the supply chains of these markets, then you can take this last step, which is to develop the supply chain capabilities needed to support the roles your company plays. This development is guided by the decisions made about the five supply chain drivers. Each of these drivers can be developed and managed to emphasize responsiveness or efficiency depending on the business requirements.

- Production—This driver can be made very responsive by building factories that have a lot of excess capacity and that use flexible manufacturing techniques to produce a wide range of items. To be even more responsive, a company could do their production in many smaller plants that are close to major groups of customers so that delivery times would be shorter. If efficiency is desirable, then a company can build factories with very little excess capacity and have the factories optimized for producing a limited range of items. Further efficiency could be gained by centralizing production in large central plants to get better economies of scale.

- Inventory—Responsiveness here can be had by stocking high levels of inventory for a wide range of products. Additional responsiveness can be gained by stocking products at many locations so as to have the inventory close to customers and available to them immediately. Efficiency in inventory management would call for reducing inventory levels of all items and especially of items that do not sell as frequently. Also, economies of scale and cost savings could be obtained by stocking inventory in only a few central locations.

- Location—A location approach that emphasizes responsiveness would be one where a company opens up many locations to be physically close to its customer base. For example, McDonald's has used location to be very responsive to its customers by opening up lots of stores in its high-volume markets. Efficiency can be achieved by operating from only a few locations and centralizing activities in common locations. An example of this is the way Dell Computers serves large geographical markets from only a few central locations that perform a wide range of activities.

- Transportation—Responsiveness can be achieved by a transportation mode that is fast and flexible. Many companies that sell products through catalogs or over the Internet are able to provide high levels of responsiveness by using transportation to deliver their products, often within 24 hours. FedEx and UPS are two companies that can provide very responsive transportation services. Efficiency can be emphasized by transporting products in larger batches and doing it less often. The use of transportation modes such as ship, rail, and pipelines can be very efficient. Transportation can be made more efficient if it is originated out of a central hub facility instead of from many branch locations.

- Information—The power of this driver grows stronger each year as the technology for collecting and sharing information becomes more widespread, easier to use, and less expensive. Information, much like money, is a very useful commodity because it can be applied directly to enhance the performance of the other four supply chain drivers. High levels of responsiveness can be achieved when companies collect and share accurate and timely data generated by the operations of the other four drivers. The supply chains that serve the electronics markets are some of the most responsive in the world. Companies in these supply chains, from manufacturers to distributors to the big retail stores collect and share data about customer demand, production schedules, and inventory levels.

Where efficiency is more the focus, less information about fewer activities can be collected. Companies may also elect to share less information among themselves so as not to risk having that information used against them. Please note, however, that these information efficiencies are only efficiencies in the short term and they become less efficient over time because the cost of information continues to drop and the cost of the other four drivers usually continues to rise. Over the longer term, those companies and supply chains that learn how to maximize the use of information to get optimal performance from the other drivers will gain the most market share and be the most profitable.

Three Steps to Align Supply Chain and Business Strategy

Professor Sunil Chopra is a keen observer of the ways that supply chains respond over time to changes in their economic and regulatory environments and to shifts in technology and customer demands. In an interview, Professor Chopra shared some of his observations.

“Look at a company's products and how they're being changed by advances in technology,” he said. “For instance, Dell's build-to-order business model and its practice of selling directly to customers are not so valuable anymore because people don't customize their computer purchases very much anymore.”

People used to buy mostly desktop PCs, but now sales of laptops surpass PCs, and people don't feel the need to customize their laptops the way they did with their PCs. “So Dell now is saying they will ship from stock instead of their traditional model, which was to build-to-order-and-ship customized PCs.”

And Professor Chopra points out that Dell is also restructuring its retail channels. Dell not only sells direct, but also sells through retailers such as Wal-Mart for standard low-end PCs. On a $500 machine the shipping expense is a significant part of the total cost, so it's better to sell low-end PCs through a local retailer like Wal-Mart

Apple, on the other hand, has a different strategy, according to Professor Chopra. “They make the user interface the customized part of their product while their hardware is a commodity. Their hardware is standard and it's the apps that run on the hardware that customize the product.”

Unlike Dell, Apple has only about 15 basic product models, and this enables them to have a simple hardware supply chain. Apple adds value to the hardware it sells by designing a user interface (UI) that customers find very attractive. So they are willing to pay premium prices for what would otherwise be commodity hardware because they want the UI that Apple puts on its hardware.

However, one of the challenges that this business model creates for Apple is that they need to have a big hit product every few years in order to keep ahead of their competitors who come out with close copies of the Apple products and offer them for sale at lower prices. For instance, just as Google's Android is starting to cut into sales of Apple's iPhone, Apple comes out with a compelling new product in the iPad. “iPad is doing well now,” said Chopra, “but they have to come up with another big hit product in another couple of years as competitors learn to copy the iPad.”

He also pointed out how regulations such as the current tax structure on Internet sales channels like the one Dell uses can influence and even distort supply chain structures. Dell is not taxed on out-of-state sales. So that causes them to remain centralized and keep using an Internet direct-sales channel when, if they had to pay out-of-state sales taxes, they would otherwise move to a decentralized model. If the regulations and tax structures related to Internet sales change, then Dell's supply chain structure will also change.

Supply chains are becoming so efficient and customer preferences change so quickly that profit margins are relentlessly squeezed. Companies need to find ways to cut their fixed costs of producing products. And they cannot risk getting too invested in a business model that emphasizes either low-cost efficiency or high-cost responsiveness. Efficiency and responsiveness are two ends of a continuum, and companies need to be flexible enough to reposition themselves on that continuum quickly when markets shift.

Professor Chopra observes that the question of efficiency versus responsiveness can be addressed like an investment portfolio question. If you are concentrated at either end of the spectrum you are in a risky position because the world will probably change suddenly and your company might not be able to adjust fast enough to keep pace.

How do you position your company or your portfolio of business to best fit the markets you serve? Some portion of your business must be responsive, so you move that part near to your customers, and another part of your business must be efficient so you position it offshore in low-cost-labor countries. In Dell's case the server market is still a market that values a lot of customization so that is the part they make responsive and Dell does server assembly onshore near its customers. But customers no longer value customization in PCs and laptops so they have outsourced that part of their business to emphasize efficiency and that work is now done offshore.

And this leads to another issue that Professor Chopra pointed out. As markets and the supply chains that serve them get more and more efficient and fluid, the middle class in developed countries tends to get hollowed out. “If you are a highly skilled worker in a developed nation, then your services are sought after and you can leverage the low-cost labor of workers in developing nations to build products you design,” said Chopra. But this also displaces large numbers of low- and medium-skilled workers in developed countries, as jobs once performed by them are sent offshore to be done by low-cost workers in developing nations.

From the 1990s through the first decade of this century, wages in developed countries have polarized. There are some who have seen their incomes increase dramatically as they leveraged the low-cost labor available in developing nations. And a lot of middle class workers in developed nations have seen their wages drop significantly because their work is now being done elsewhere. “This produces greater value for the world as a whole, but now the question is how are we going to distribute that value in order to maintain a broad middle class in the developed countries?”

Professor Sunil Chopra is the IBM Distinguished Professor of Operations Management at Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management. He has co-authored the books Managing Business Process Flows and Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation, 4th Edition.

Chapter Summary

A supply chain is composed of all the companies involved in the design, production, and delivery of a product to market. Supply chain management is the coordination of production, inventory, location, and transportation among the participants in a supply chain to achieve the best mix of responsiveness and efficiency for the market being served. The goal of supply chain management is to increase sales of goods and services to the final, end-use customer while at the same time reducing both inventory and operating expenses.

The business model of vertical integration that came out of the industrial economy has given way to “virtual integration” of companies in a supply chain. Each company now focuses on its core competencies and partners with other companies that have complementary capabilities for the design and delivery of products to market. Companies must focus on improvements in their core competencies in order to keep up with the fast pace of market and technological change in today's economy.

To succeed in the competitive markets that make up today's economy, companies must learn to align their supply chains with the demands of the markets they serve. Supply chain performance is now a distinct competitive advantage for companies who excel in this area. One of the largest companies in North America is a testament to the power of effective supply chain management. Wal-Mart has grown steadily over the last several decades and much, if not most, of its success is directly related to its evolving capabilities to continually improve its supply chain.