Evil by Design

The adjective “Machiavellian” is used to describe someone who aims to deceive and manipulate others for personal advantage. However Niccolò Machiavelli just used his observations of contemporary and historical affairs to suggest the courses of action that were most likely to help 16th-century statesmen (“princes,” or more accurately “merchant princes”) succeed. As such, he was a data-driven commentator. Some of the courses of action he recommends are less virtuous, but the more virtuous princes, as he mentions, did not often succeed. He was interested in setting down the facts and leaving the actions and moral judgments to someone else.

This book gathers observations from contemporary and historical computer applications and websites to suggest the courses of design action that are most likely to help modern-day entrepreneurs (the merchant princes of Silicon Valley) succeed.

The principles laid out in each of the seven deadly sin chapters can be applied either for good or for evil. How far you take it is up to you. There is a continuum from persuasion to deception. That continuum takes in everything from being totally open, through being economical with (or neglecting to mention) certain truths, through bent truths and white lies, to all-out deception. I would not go so far as to advocate lies—if nothing else because lies are difficult to recover from if you are found out. However, this book wouldn’t sell half so well if it were called Slightly Naughty by Design.

In addition, you can use this information to recognize and avoid being personally persuaded by these principles when they appear on sites you use.

Should you feel bad about deception?

My grandfather was a grocer. He owned a store in a small village. This was in the days when you would enter a store with your shopping list, and the grocer would fetch all the items for you off the shelves, rather than making you walk around and collect them yourself. Among the many products he sold, my grandfather was renowned for his Cheddar cheese. Certain customers liked their cheese mild, whereas others liked it strong. My grandfather knew their preferences and, like all good salesmen, he would talk up how good the cheese was. “Ah, Mrs. Jones, we have some lovely creamy mild Cheddar this week—in fact I’ve got some set aside for you,” or “Mr. Smith, how about some more of that sharp Cheddar? It’s good stuff, isn’t it?”

My grandfather would disappear into the back of the store and reappear with a hunk of cheese wrapped in greaseproof paper to be weighed on his balance scales. What the customers didn’t know was that sometimes the farmer who supplied the Cheddar would run low, meaning that there was only one round of cheese available in the cold room. In those instances both the strong and the mild cheese were cut from the same block. Undoubtedly, Mrs. Jones still enjoyed her mild Cheddar just as much as Mr. Smith enjoyed his sharp Cheddar.

Was my grandfather, a decorated veteran, being deceitful? Maybe. Was there more benefit to him than to his customers? In some respects yes—no lengthy explanations were required, and he still made the sale. Were his customers hurt by his actions? Quite the contrary. They probably savored their cheese even more, knowing that it had been chosen especially for them by their favorite grocer. Much of the effectiveness of the transaction was tied up in the suggestion of the cheese—what it represented—rather than the actual article itself.

On the outside, a typical quiet village grocer’s store. On the inside, a den of deception.

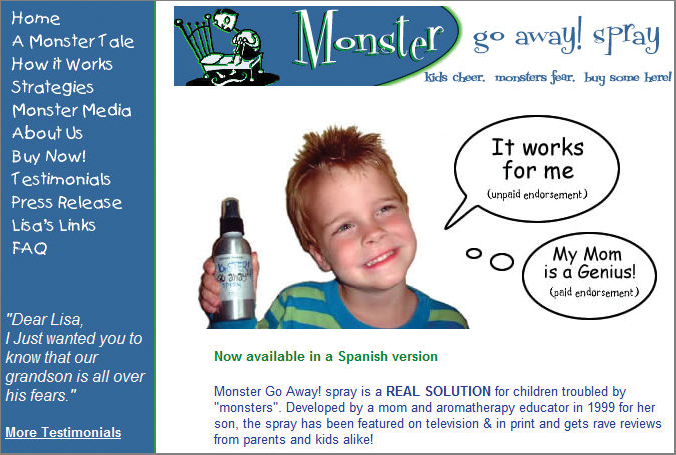

Deception helps this cute kid sleep well at night

Young children often worry about monsters under the bed or in the closet. Pixar even created a successful movie franchise around this idea. Rather than resorting to rational reassurance (“there’s no such thing as monsters”), researchers Liat Sayfan and Kristin Hansen Lagattuta at the Center for Mind and Brain at the University of California, Davis, suggest that especially for younger children it is more useful to resolve the issue by staying within their imaginary world. Giving the child a way to be powerful against the monsters, or to see the monsters as less scary, helps much more than dismissing the idea of monsters.

This, of course, is deception. It appears from their research that the kids are willing participants in the deception. Even the 4-year-olds in the study knew that monsters weren’t real, but they coped better when resolution was framed in terms of the imaginary world.

And that willing complicity in the deception leads to product opportunities. “Monster Go Away!” spray is a dilute mix of lavender oil in water, packaged specifically with monster banishing in mind.

A shot from the monstergoaway.com site in 2009. The site is no longer active, but the product is still sold.

Deception helps the elderly and infirm stay safe

Many Alzheimer’s patients living in care get distressed when their long-term memories conflict with their current situation. As dementia sets in, they are less able to remember current events and get concerned that they should be returning to the house or companions of their past. Richard Neureither, the director of the Benrath Senior Center in Dusseldorf, suggests that rather than fight this “People with dementia live in their own world. They are not open to rational arguments. One must meet them in their own version of reality.”

Fake bus stop outside the Sana care facility for Alzheimer’s sufferers (Dusseldorf, Germany). Photo © Associated Press.

The answer, pioneered by Franz-Josef Goebel, chairman of the Dusseldorf Old Lions Benefit Society, was to create a fake bus stop outside the care facility. Because the residents are free people, they cannot be locked up or restrained with drugs. Some can also get violent when told they can’t leave. By walking the residents to the bus stop—a symbol that many associate with returning to their home—staff can give the residents a sense of accomplishment. Because their short-term memory is not sharp, the residents soon forget why they were waiting for the bus. “We invite them in for a coffee and after five minutes they forget they even intended to leave.”

The idea, first implemented at two locations in 2008, was sufficiently successful to be repeated at care homes in Munich, Remscheid, Wuppertal, Herten, Dortmund, and Hamburg.

These three examples, the cheese, the monster spray, and the bus stop, all come from the physical world. However companies practice benign deception in the digital realm as well. As part of their “Real Beauty” online awareness raising campaign, the skincare company Dove created a Photoshop action (a downloadable feature that automates a normally time-consuming photo editing activity) that claimed to add “glow” to models’ skin. They distributed it on several online Photoshop forums. They were however being deceptive. The action was really designed to revert all changes to the image it was applied to, and to display the message “Don’t manipulate our perceptions of real beauty” on-screen. The action could subsequently be undone, so that photo retouchers’ work wouldn’t be lost. In reality it’s unlikely that professional photo retouchers would be downloading free Photoshop actions. It’s more likely that Dove’s ad agency Oglivy spotted an opportunity for a feel-good story. However, the advert is deceptive on either level.

It’s fair to say that most of the design patterns in this book don’t need to be deceptive in order to be persuasive. In the introduction I said that the truly great evil designs are ones where people will enter willingly into the deal even when the terms are exposed to them. However, many of the patterns become easier to implement when they are disguised or when they use misdirection.

Should you feel bad about using the principles in this book?

In 1999, Daniel Berdichevsky and Erik Neuenschwander, both at Stanford’s Captology lab, proposed eight Principles of Persuasive Technology Design. These principles have subsequently become a mainstay in the realm of persuasive design. Their eighth and “Golden” Rule of Persuasion is that “The creators of a persuasive technology should never seek to persuade a person or persons of something they themselves would not consent to be persuaded to do.”

This may not always be the case. Is it okay for a smoker to make an iPhone app to help others quit smoking? How about for an atheist to build a website for a church that seeks to recruit new members? Persuasion can be used to good or to bad effect. In both cases, the creator would not consent to be persuaded by the message yet many would see their actions as laudable.

Berdichevsky and Neuenschwander go on to state that deception and coercion are unethical. However, as we’ve already seen there are times when they can be very practically applied towards positive ends. Any parent will tell you about the numerous white lies they tell and the bargains they forge with their young children just to get through the day without resorting to infanticide. Humor often works by being deceptive. A joke is funny because the situation resolves in a different way than we anticipated. Warning people of this fact before telling them the joke would not be particularly effective.

Often the given test of whether a practice is deceptive or not is whether the individual would have consented to it if full information had been available. The implication is that individuals would not consent to deceit. But how does that help us when we encounter situations in which deception could be seen as both positive and necessary? The children in Sayfan and Lagattuta’s monster studies responded better when they stayed in the world of monsters in order to address their fears, all the while knowing that the monster world was make-believe. The families of the Alzheimer’s patients consented to use of the bus stop as a distress-reducing tool and most likely, if it had been explained to them before their condition became too advanced, so would the patients themselves. The alternatives—restraint or drugs—seem less ethically acceptable than the deceptive bus stop sign. In these scenarios, the individuals were fully complicit in their own deception.

So perhaps persuasive techniques that use deception or appeal to sub-conscious motivations can have positive or even ethical outcomes. The Golden Rule should probably be seen more as a Golden Guideline.

It’s okay to make money

Capitalist enterprise suggests that it’s okay to profit from business because it keeps you productive and it keeps you innovating. Economic theory suggests that it’s in the capitalist’s best interest to provide a satisfactory level of service to customers. There is not an implicit tension between these two goals. What you must decide is how far to push the benefit in your direction rather than in your users’.

Somewhere there is a boundary that distinguishes good business practice from evil design. There is a line to draw. Crossing that line puts you in the realm of con artists and criminals. However, the line is wavy. It moves based on public sentiment, political will, judicial powers, and personal moral imperatives.

It’s easier to make money from happy customers

If you’re doing things right, your users still value the service you provide because it is about more than just money. There’s a large element of intangible benefit as well.

There are many kinds of intangible benefits. There is real value to users in providing hedonic satisfaction or the feeling of having worked hard to achieve something. If you provide users with a tangible product as well, then good for you.

Ultimately, you’re making people happy. People part with their money for many other things in life that make them happy (and many that do not). In fact, the happier you make them, the more of their money they will offer you. Doing something that makes people unhappy is not a good business strategy.

Awareness is half the battle

Don Norman, in his book Emotional Design, states that we’ve always used affordances (how an item invites people to use it) and intents (what people want to achieve) to control user behavior. Often though, we’ve done so without knowing how or why the designs we created worked the way they did. This book lists the patterns that make the affordances and intents explicit. Now you know why you’re doing what you’re doing. You can be purposeful in your designs.

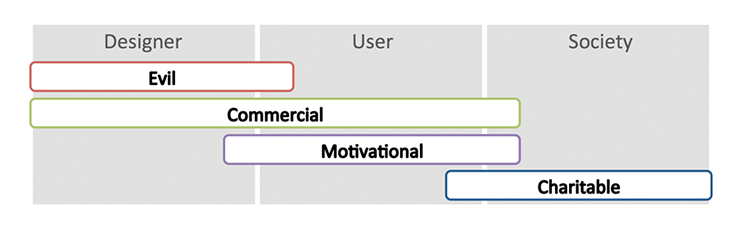

The introduction said evil design creates purposefully designed interfaces that make users emotionally involved in doing something that benefits the designer more than them.

Now perhaps some readers of this book care about more than just turning a quick profit and slinking off into the night. Maybe you want to create a sustainable business, or have even loftier goals such as getting people to lead healthier lifestyles or contribute to a charitable cause. You can extend the definition of evil design to accommodate these situations.

- Commercial design creates purposefully designed interfaces that make users emotionally involved in doing something that provides an equitable benefit to the designer and the user.

- Motivational design creates purposefully designed interfaces that make users emotionally involved in doing something that benefits them even though they would not chose to do it unaided.

- Charitable design creates purposefully designed interfaces that make users emotionally involved in doing something that benefits society more than either themselves or the designer.

Who benefits? Your aims determine your approach. Are you just in it for the cash, do you want to create happy customers, do you want to motivate users to improve themselves, or do you want them to give to others?

- Be purposeful: Approach each area of your product or service with persuasion in mind. Actively consider which patterns might be beneficial in that area.

- Appeal to emotions: Remember that benefits don’t have to be tangible in order to be appreciated.

- Keep the benefit apparent: Evolve the interface to maximize your desired outcome without removing the perceived benefits to your users.

- Design for satisfaction: Satisfied customers will be more likely to return. Charitable, motivational or commercial designs will be more likely to satisfy customers in the longer term than will evil designs.

- Beware groupthink: Discuss your plans with several not-like-minded individuals before implementation in order to check your ethical and business assumptions.

- Measure success: Test an early prototype with potential users to gauge reactions and tailor the interface. After release, capture feedback and metrics from real customers at every opportunity. It may take several iterations to fully achieve your desired effect.

Be purposefully persuasive

The patterns in this book are written so that you can take advantage of them for any of these different end goals: evil, commercial, motivational, or charitable persuasion. Some of the examples shown in this book might make you wince. Others might make you laugh. Still more of them might be sufficiently inspirational that you integrate them into your business practices.

Whether you intend to create evil, commercial, motivational, or charitable designs, make sure you do so purposefully rather than accidentally. Engaging users on an emotional rather than rational level is the key to persuading them to become involved.