Gluttony

Too soon, too expensively, too much, too eagerly, too daintily.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 1274

Gluttony occurs when we over-consume to the point of extravagance or waste. Historically gluttony was seen as a major sin (it distracted people from their religious observances), but today it’s almost as if gluttony is expected in Western culture. We demonstrate our wealth by showing an overabundance of “stuff.”

Companies encourage this overabundance by making us feel like we deserve to be rewarded and by escalating our level of commitment beyond what we first intended, drawing us in from early engagement through to full-on compliance. Sites also make us fearful of missing out—scarcity, exclusivity, and loss aversion play on the fears behind gluttony.

Deserving our rewards

We are easily fooled into gluttony. Just having healthy options available on menus or among the selections from a vending machine is sometimes enough to make our brains think we’ve satisfied our health and nutrition goals, and therefore have permission to choose less honorable options.

The average restaurant meal in the United States is four times larger now than it was in the 1950s, yet we might still be fitting into the same size clothes as we always have—not because we’ve stayed slim, but because our clothes have grown. Not in the sense of Betabrand’s gluttony pants, which have three waistline buttons labeled piglet, sow, and boar “to accommodate waistline expansion during feeding time,” but because what was a size 14 dress in the 1970s is not the same size garment today. The Economist found that women’s size 14 (UK) clothes are about 3 inches larger in the hips than they were in 1970, thus about the equivalent of a 1970s size 18. Men’s clothes also lie: A recent Esquire investigation found that some brands of 36-inch trousers actually measured as much as 41 inches.

The one thing this expansion does is makes us feel good about ourselves—we can still fit into the same size clothes as we did years ago, and so we feel flattered and thus more likely to buy from the companies that accommodate us.

Betabrand’s Gluttony Pants: “The first trousers equipped with their own napkin.” (betabrand.com)

Gluttony is about conspicuous consumption, about finding bargains regardless of whether the bargain item was a necessary purchase, and about a feeling that we deserve what we purchase.

From a persuasion perspective, gluttony is actually an easy way to draw people in. With the apparent lack of embarrassment about gluttony in current Western culture, all that is required is to make people think, “I’ve earned it; I deserve it.”

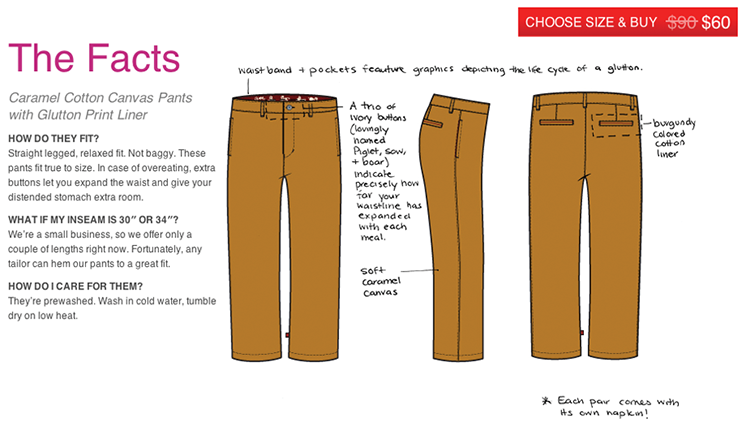

A map to encourage gluttony—navigate not by famous landmarks, but by store locations. (citymaps.com)

Canadian Tire is a retail and automotive service company with more than 480 stores across Canada. In 1961 it introduced Canadian Tire Money as a fuel purchase loyalty program, giving customers Canadian Tire “bank notes” as a reward, at a rate of 5 percent of the fuel purchase price.

Over time the reward proportion has fallen to 0.4 percent of purchase price, but even this relatively meager return hasn’t stopped customers from saving the notes, even for inordinate lengths of time. It took one Edmonton man 15 years to save enough rewards to purchase a ride-on lawnmower. The mower was priced at $1,053, which required Canadian Tire money equivalent to spending $263,250, or $17,550 per year, at the store.

Canadian Tire money is also often accepted at other locations in the country. The folk singer Corin Raymond collected donations of the currency to pay for $3,500 of recording studio time for his album Paper Nickels, which includes a song with the refrain “Don’t spend it honey, not the Canadian Tire money, we’ve saved it so long.”

Corin Raymond used Canadian Tire money donated by thousands of individuals to finance album production. Many of the bank notes in this image are 5 cent, 10 cent, or 25 cent denominations. (dontspendithoney.com)

It appears that despite the seemingly tiny savings that Canadian Tire and other similar discount schemes provide, they attract fervent audiences. The question is, why?

Seth Priebatsch, a gamification expert who runs the company SCVNGR, suggests that just handing a coupon to customers means that they will assign a value to it equal to its redemption value. However, if they have to unlock, win, or otherwise work for that coupon, then there is an additional emotional impact that translates into additional perceived value for the individual.

Purchasing items to save tiny denomination Canadian Tire “bank notes” toward a challenging and seemingly unattainable goal fits nicely into this category.

The most value to the business is when the user perceives that there is more personal value than the face value of the coupon. A hard-won $1 discount may be worth disproportionately more in terms of loyalty than handing out $5 vouchers to everyone who enters the store.

The best perceived value occurs when the barrier to getting the discount is set at the correct height so that the right number of customers decide it’s worth the effort or risk to participate. It’s likely to be the most ardent (hopefully this equates to the most valuable too) customers who are prepared to jump through the most hoops.

- To make customers value even a small reward, make them work for it, either by collecting items over time or by performing a task to get the reward.

- Increase the perceived value of the reward by making it harder to achieve, but keep it sufficiently attainable so that the right number of customers will act.

- Use language such as “winning” or “award” rather than “coupon” to make it clear that effort was involved in attaining the prize.

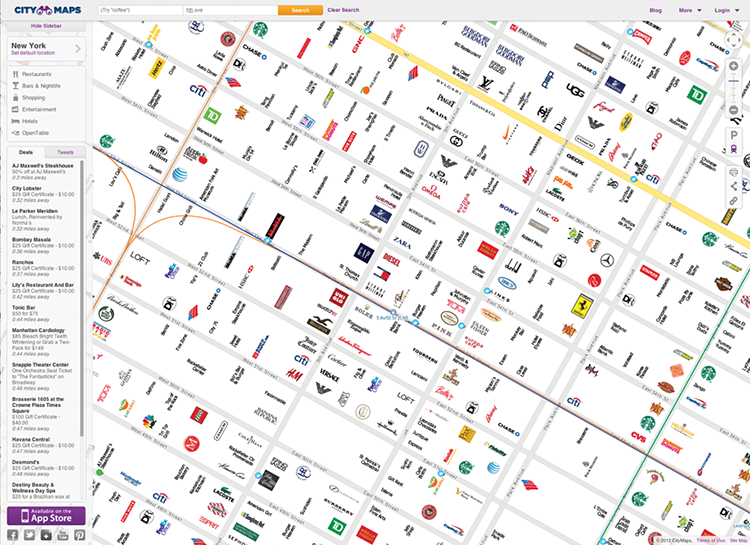

Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk is an online marketplace where individuals get paid to perform small tasks that computers aren’t good at, such as making preference choices, composing descriptive sentences, searching for an item in an image, transcribing audio, or extracting meaning from phrases. These tasks are called Human Intelligence Tasks or HITs.

Anyone can set up a HIT, using Amazon.com’s platform to advertise and host the tasks, and anyone can work on HITs; although, some require workers to take a simple test first, or to meet certain demographic criteria. Amazon.com takes a 10 percent commission for running the site.

The HITs are normally broken down into small chunks, and individuals who complete them (“providers”) get paid for their time. But the rate of pay isn’t exactly high. Finding the e-mail address for a given individual might pay 3 cents/person. Copying and pasting the most relevant search result for a given keyword could pay 12 cents/keyword. The highest paying gigs, requiring real skills, provide approximately $40 for transcribing a 2-hour voice recording.

Analyzing the self-reported earnings on a couple of the popular provider forums suggests that committed individuals will make approximately 10 cents per HIT, and earn approximately $3.80 per hour full-time equivalent if they are U.S.-based and therefore can access all the HITs. That is just slightly more than half the federal minimum wage.

But despite this low payout, providers (who tend to refer to themselves as Turkers) keep coming back. One commenter, posting on Turkernation.com says, “I am spending way too much time on turking, kinda like when I used to play WoW. Do you guys find it addictive? The payout is like a score, and as you get qualifications, it's like getting levels. It's like I'm playing a game.”

Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk—in this HIT, you’ll earn six cents for checking the classification of a set of products on the site.

Why do people commit so much time to something that—even for experienced Turkers—pays out so little? For some people, there are good reasons: unemployment, ability to work from home in micro-shifts between other tasks such as child minding, or the ability to work from work—either students during dull lectures, or others at their regular workplace using their work Internet access.

For other people, the reasons are much less solid. They revolve around setting goals to reduce debt, to have “toy fund” money for frivolous expenditures, and simply being entertained: “Why not get paid for sitting at the computer, which I would be doing anyway?”

Lots of these reasons appear to be justifications that attempt to remove the cognitive dissonance of doing something that isn’t actually particularly “worthwhile” in financial terms. And that fits in nicely with some findings from way back in 1959 when Leon Festinger and James Carlsmith found that in situations where there is cognitive dissonance between effort and return, people will be forced to create justifications for working so hard for a small reward, thus increasing their perceived value of the reward. Giving a larger reward just fits into their expectations and so doesn’t create dissonance that needs to be resolved.

Festinger and Carlsmith ran an experiment where people conducted a boring and repetitive task for a period of time. After the study, they gave participants either $1 or $20 in 1959 money in return for lying to the next participant about how interesting the study was. When subsequently asked about their own experiences of the study, participants who had been paid only $1 to tell the lie rated it as more interesting than participants who had been paid $20, despite both telling the same lie to subsequent participants.

It seems that participants who were paid $20 to say how great the study was found it easier to justify their lying (they were paid well to lie) than students who were paid only $1. That meant that the people in the $1 situation had to rationalize the boring task in their minds and believe it was actually interesting to overcome the cognitive dissonance of lying about it.

As Festinger said, “If a person is induced to do or say something which is contrary to his private opinion, there will be a tendency for him to change his opinion so as to bring it into correspondence with what he has done or said. The larger the pressure used to elicit the overt behavior … the weaker will be the…tendency.”

So a small reward (or the threat of mild punishment) forces the participants to create their own justifications for their actions, whereas a large reward (or large threat) provides an external reason. Counterintuitively, if Turkers were paid any more, they may start comparing the work to other potential work they could be doing and start seeing it less like entertainment and more like a badly paying chore.

- Provide just a small reward to make people create their own reasons for participating. They will come to believe and defend those reasons as a way to resolve cognitive dissonance.

- It might help to also subtly provide a couple of sample justifications that people could use to help accept this small reward.

You too could win an iPad for only 30 cents if only you were bidding on this auction site! (dealdash.com)

You have probably seen the adverts—iPads (or whatever other gadget is hot right now) being sold for ridiculously cheap prices. The chapter on Lust covers the motivating factors that make people want shiny devices like these, but this is a good place to consider the gluttonous element of the transaction—why somebody would feel that they can actually get a $500 piece of hardware for under $5.

One site lists nearly 40 companies working in the online penny auction or “entertainment auction” space. Take arrowoutlet.com as an example; although sites such as flutteroo.com, bidstick.com, swoopo.com, and many others employ similar strategies.

First, you buy a package of “bids” at 50 cents each. Bids allow you to enter auctions for items. Auctions are timed, but each bid extends the closing time by a set amount (normally 15 seconds). The winner is the last bidder when the timer runs out. Obviously then, there is an element of excitement (winning something), urgency (the ticking clock), and competition (other bidders). All this conspires to mask some simple accounting issues.

Studying the selling price for one item (iPad 2 16Gb Wi-Fi) over the course of one week in 2011, the average selling price was $120. To be clear, that means the winner of the auction can now buy the item for $120. This does not account for the number of bids that they spent to win.

Now, because each bid raises the price of the item by 1 cent, you know that there were 12,000 bids on average per iPad. 12,000 x $0.50 = $6000. $6000 + $120 = $6120.

Apple’s own site sells the same model for $499, so the revenue per iPad to arrowoutlet.com is $5621. It needn’t even hold stock of the item because it can drop-ship it directly from Apple. The sites often claim to lose money on a large proportion of their auctions. However, there is no need to feel sorry for them. Apparently the losses are more than compensated for by the 1100 percent profit on high-ticket high-desirability items such as iPads.

Ned Augenblick at Berkeley used an algorithm to capture the statistics for 166,000 auctions and found that auction revenues typically exceed 150 percent of the value of the item being auctioned, as long as the site has a sufficiently high number of bidders for each active auction so that the war of attrition continues for long enough to bid the price up. Auctions for direct cash payments return an average profit margin of 104 percent—the site makes a dollar in profit for every dollar they auction!

It’s easy to argue that the winner still got a bargain—the cost for the iPad was $120 plus the winner’s share of the bids. However, most auctions end with two people bidding against each other for some time (the sites even have bid-o-matic robots that can automate this process for you), so the winner most often provides a disproportionate number of the bids. And then there are the auctions that the bidder doesn’t win. It’s possible to sink a lot of bids into an item and then “lose” to somebody else. Because each bid costs you money regardless of whether you eventually win the product, total expenditure on the site can easily be more than the retail value of the products you end up “winning.”

A couple of interlinked psychological and economic principles are at work here: irrational escalation of commitment and the sunk cost fallacy (a form of loss aversion).

You place a couple of bids on an auction in its later stages, and now you are in the game. Soon you realize that your 50-cent bids are raising the price by only 1 cent each time. You’ve spent quite a bit of money and bidding is still quite active, extending the time of the auction. But you made the decision to start bidding, and losing now would be costly, so you feel like you have to continue. Maybe you just want to win—to beat the other bidders who you’re competing against. You figure they’re in just as deep as you are. This reluctance to admit past mistakes and need to justify prior behavior is irrational escalation of commitment.

At some point, you end up in a position where your sunk cost (the amount you’ve spent in 50-cent bids) when added to the purchase price of the item will exceed the actual value of the item. The cost has now outweighed any future benefit, but irrational escalation of commitment keeps you going because you feel you can still win and recoup some of your losses. You basically continue to bid because of how much you’ve already bid. This is the sunk cost fallacy.

Augenblick collected data from six different penny auction sites and showed that auctions are less likely to end, and bidders are less likely to leave an auction as they make more bids. Both behaviors are indicative of sunk cost fallacy behavior, and both drive up the cost of the auctioned item.

In the case of these penny auctions, irrational escalation of commitment is thankfully short-lived for most bidders. Augenblick found that 75 percent of bidders left the site before placing 50 bids, and 86 percent stopped before placing 100 bids. However, that did leave a hardcore set of active bidders, most of whom struggled to break even, let alone to make a profit. On one site, Swoopo, the most experienced 11 percent of bidders contributed more than 50 percent of the site’s profit.

Of course, none of the penny auction sites spell it out exactly like this. It is important for the auction sites to maximize the number of bidders per auction, and the best way to do that is to get customers excited about the low purchase price for each item, tell them how to win the opportunity to buy it, and then sell them a chunk of bids to play with. Even their tutorials are designed to provide step-by-step instructions for placing bids rather than an explanation of the underlying process. And this is on purpose. Any mention of the sums would dampen bidders’ enthusiasm before they had sufficiently escalated their commitment.

- Make the arithmetic associated with your product hard to perform.

- If possible, add confounding factors such as urgency, excitement, or competition so that users focus on these rather than the math.

- Use familiar terminology, but make the words mean something slightly different. For instance, in traditional auctions bids cost nothing unless you are the winner, whereas in penny auctions, bids cost money the moment they are placed.

- Automate the process of spending money wherever possible so that it slips out of awareness for people.

- Provide tutorials that explain how easy the process is without pointing out the implications.

- Use tokens to remove the sense of spending real money (see more on this in the chapter on Greed).

- Make a clear statement about the value of the item being auctioned/sold, but neglect to mention associated costs.

- Keep people interested until they reach the point of irrational commitment by having sufficient cost sunk in the item. From then on, psychology will do your work for you.

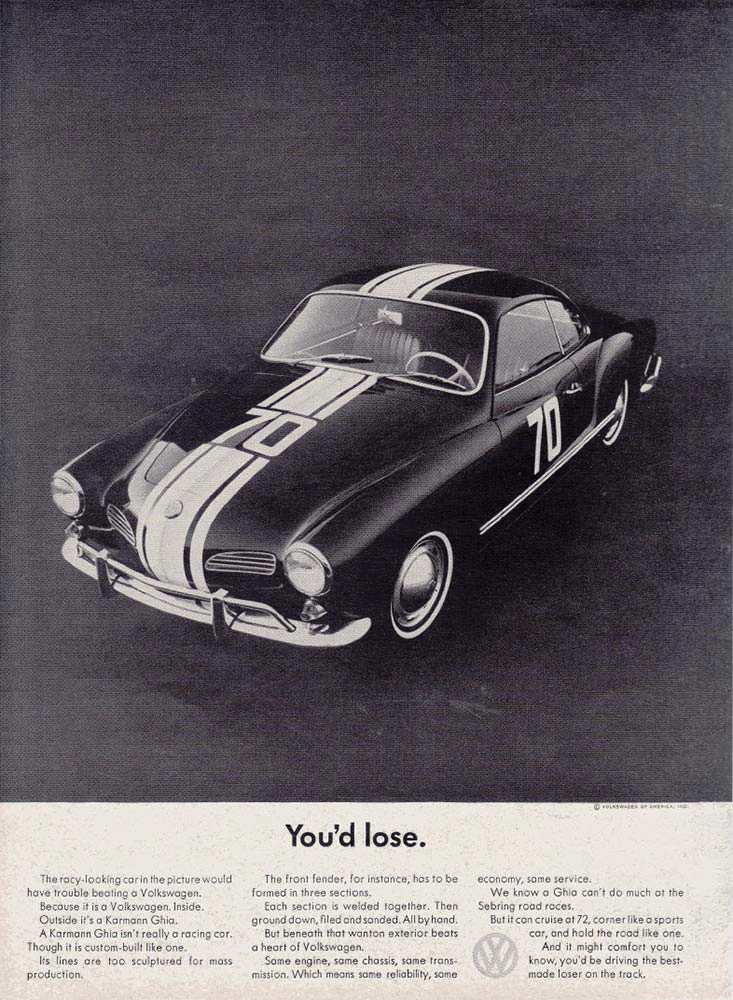

The original Volkswagen beetle was sold via a long series of self-deprecating advertisements. The honesty and humor in each ad made people more open to the strengths that followed.

The Karmann Ghia looked like a sports car, but was just a Volkswagen Beetle underneath. This advert reinforces the sporty looks while simultaneously making fun of it. The flip side that draws you in is the practicality and fuel economy of the vehicle. (Ad agency: Doyle, Dane and Bernbach, 1964)

Although it’s tempting to hide flaws, it is often beneficial to mention weaknesses or issues with your product or service before customers find out. They’ll subsequently trust you more because you have shown that you have the integrity to be open and honest with them.

We are wired to reciprocate, and so when someone has already apparently demonstrated that they are trustworthy, we reciprocate by trusting them in return.

Just be sure to follow the weaknesses up by mentioning strengths that customers can use to justify continuing to do business with you. The positive reasons should be related to the weakness. In other words, if the weakness were cost, follow up with talk of economy (“This LED light bulb costs more to buy, but it lasts 10 times longer, so you’ll make your money back and more over the life of the product”), rather than talk of the quality of the light, which is an unrelated topic.

Without a basic level of mutual trust, commerce would never happen. The vendors must trust that they’ll be paid, and the customers must trust that they’ll receive the goods. Rising above the default by demonstrating that the trust was earned is a way to cement the relationship.

That raises a more ethically challenging question, “Is it worth CREATING a trust incident to recover from?”

You could argue that manufacturing and then recovering well from a trust issue is a way to create more trust. Machiavelli saw this as a legitimate tactic.

Without doubt princes become great when they overcome the difficulties and obstacles by which they are confronted, and therefore fortune, especially when she desires to make a new prince great, who has a greater necessity to earn renown than an hereditary one, causes enemies to arise and form designs against him, in order that he may have the opportunity of overcoming them, and by them to mount higher, as by a ladder which his enemies have raised. For this reason many consider that a wise prince, when he has the opportunity, ought with craft to foster some animosity against himself, so that, having crushed it, his renown may rise higher.

Machiavelli, The Prince, Ch. 20, pt. 4

Nowadays there are probably several cheaper strategies than resorting to manufacturing a trust incident. The Online Trust Alliance reports that data breach incidents cost U.S. companies $318 per customer in 2010. That much money could probably buy a lot of trust.

Recently however it appears that many organizations haven’t had to purposefully create these incidents, as they’ve been happening to them unbidden. “Fortune causes enemies to arise…” and all that.

The typical path appears to be to first hide the problem, then deny it, then understate it, and finally admit it but do little to reassure customers. Although hiding the issue may seem like the ideal evil route, it’s actually the stupid solution.

Graham Dietz and Nicole Gillespie, writing for the Institute of Business Ethics, say “An organisation can demonstrate its trustworthiness through the technical competence of its operations, products and services (ability), as well as through its positive motives and concern for its multiple stakeholders (benevolence), and honesty and fairness in its dealings with others (integrity).”

A smart organization would exploit the situation caused by a trust incident by owning the issue and turning it into a positive trust experience (ability) so that customers feel better disposed toward the company in the future (integrity), having proof that the company is prepared to take care of them (benevolence).

First, look at a company that has become the poster child for letting events get ahead of them: Sony Corp.

Between April 17 and April 19, 2011, somebody broke into the servers hosting the Sony PlayStation Network and stole details of 77 million customer accounts, including information such as name, address, birth date, e-mail addresses, and login passwords, and potentially credit card information including billing address and security question answers.

Sony initially closed down the network and displayed “undergoing maintenance” screens to users. Although it subsequently appeared that it was working hard behind the scenes to find out exactly what had happened and what data was involved, it took until April 26th—more than a week later— to admit that personal details may have been compromised. At that point, Sony did not do much to placate angry users, instead just pointing people to the three U.S. credit reporting agencies and federally available ID Theft information. It was only after significant pressure from Congress that Sony decided to offer ID theft insurance to all users for 12 months—a distinct lack of benevolence.

Twenty-three long and low-communication days later, Sony brought the service back online, and pointed users to a password reset page to re-enable their online accounts. Adding insult to injury, this page soon had to be taken down because it turned out to be exploitable; you could reset someone else’s password just by knowing his e-mail address and date of birth. This didn’t do much to improve customers’ perception of Sony’s capability or concern for its customers.

Although Kazuo Hirai, chief of Sony Corp.’s PlayStation video game unit, said, "I see my work as first making sure Sony can regain the trust from our users," and Sony offered “welcome back” freebies such as complimentary game downloads and 30 days of free service, user reaction was not positive. The lack of communication and the seeming reluctance to “do the right thing” for customers seriously hurt Sony’s reputation in the gaming world. Actions such as changing the terms and conditions document for the PlayStation Network to limit users’ legal rights if the same thing happens in the future suggest that Sony is still taking a defensive rather than proactive approach to user trust, further damaging any concept of its integrity.

In contrast, consider the case of the University of Michigan Health System, a group of hospitals that, when they identified a medical error, pre-emptively reached out to affected patients and their families, communicating openly and honestly about the issue and its ramifications. This is in direct contrast to the majority of healthcare providers, that seem to work on a principle of “deny and defend” when faced with an adverse event.

Contrary to popular assumptions, the University of Michigan Health System found that rather than reaching out being seen as an admission of guilt and an invitation for more lawsuits, this pre-emptive approach halved the number of claims, reduced the claim resolution time from 20 to 8 months on average, and halved the cost of compensation awards.

It seems that many patients who file malpractice lawsuits do so mainly to understand what happened and why, and through a need to prevent the same incident from happening to others in the future—or to use Dietz and Gillespie’s language, they are motivated by integrity. By acknowledging errors and apologizing, the healthcare provider removed the primary motivation for legal action. When legal action was undertaken against the University of Michigan Health System, 71 percent of the plaintiffs’ lawyers settled for less than it anticipated, and 57 percent said they chose not to pursue cases they would have pursued before the program was in place.

A similar program at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Lexington, Kentucky, led to average malpractice payouts of $14,500 per case. That compares favorably to payout rates at other VA facilities, which averaged $413,000 for malpractice judgments, $98,000 for pretrial settlements, and $248,000 for in-trial settlements. Despite having more claims overall, probably as a result of improved patient awareness, the Lexington VA hospital still had the eighth lowest total claims payments among all VA hospitals. As a sign of the financial and moral value of this approach, these full disclosure policies have now been adopted at all 35 VA hospitals in the United States, as well as several other private healthcare institutions in the United States, Canada, and Australia.

So, show the problems. Turn issues into positive trust incidents. Counterintuitively, this may cost you less in financial terms while also giving you much more moral currency with your audience.

- See weaknesses as an opportunity to build trust rather than as something to be hidden away. It’s better that you manage the message around the weakness rather than leaving it to people external to the company who will shape it to their own advantage.

- Be open and honest. It’s hard to over-communicate, especially in times of crisis.

- If you find yourself in a trust incident, think how you will demonstrate your technical competence (ability), concern (benevolence), and fairness (integrity).

- Ability: Have a pre-prepared plan and policy for how you’ll handle trust incidents. Acknowledge that a trust incident will cost you money, but that it’s also an opportunity to manage losses and demonstrate aptitude.

- Integrity: Stick to facts, not speculation. Even if the fact is, “We don’t know the answer yet,” it’s important to remain accountable rather than having to backtrack later.

- Benevolence: Demonstrate that you have given affected people more than was expected in terms of apologies and recompense.

Escalating commitment: foot-in-the-door, door-in-the-face

Reciprocity describes people’s behavior when they are given something. It is in our nature to feel more charitable toward the gift giver, and therefore more likely to do something for them in return—in other words, to reciprocate.

At some point in the past you may have received “free” address labels from a charity, or “yours to keep whatever you decide” samples from a company. This is a calculated investment. The charity or company knows that on average, recipients will be more likely to give or spend if they are reciprocating for a gift that was given to them. In fact, it’s worth researching charities before contributing to them. At least one charity hit the news recently for using more than 80 percent of its donations in marketing costs, primarily through sending out gifts to new potential donors.

Two old tricks to create reciprocity started in the real world and have found their way online despite being somewhat tied to physical events. Both were originally practiced by door-to-door salesmen, hence the names foot-in-the-door and door-in-the-face.

When people see the value (or at least the lack of harm) in agreeing to a small favor, they will be more likely to commit to a larger one.

This sales technique has been used for centuries. Door-to-door salesmen would ask the owner of a house if they could at least come in to demonstrate their product, perhaps in the process leaving the owner with a cleaner floor or windows. Door-to-door fundraisers might first ask residents to sign a petition, and after the resident complied with that small request, the fundraiser would later come back and ask them to make a donation. Studies show that more people donate after agreeing to the initial petition request than if they are just asked for money.

In the online world, participants in one study were more likely to fill in a survey sent through e-mail if they had previously responded to a much smaller question sent by the same individual.

On the web, asking for an initial small favor might mean asking for only the bare minimum of information that you need to set up a relationship with someone. This could be a ZIP code to allow personalization, or an e-mail address to save information for later.

In these situations, asking for more information would most likely be a turn-off for users of the site. Not having a deep relationship with the site, and not understanding its value to them, they would refuse to give particularly detailed information and would instead leave.

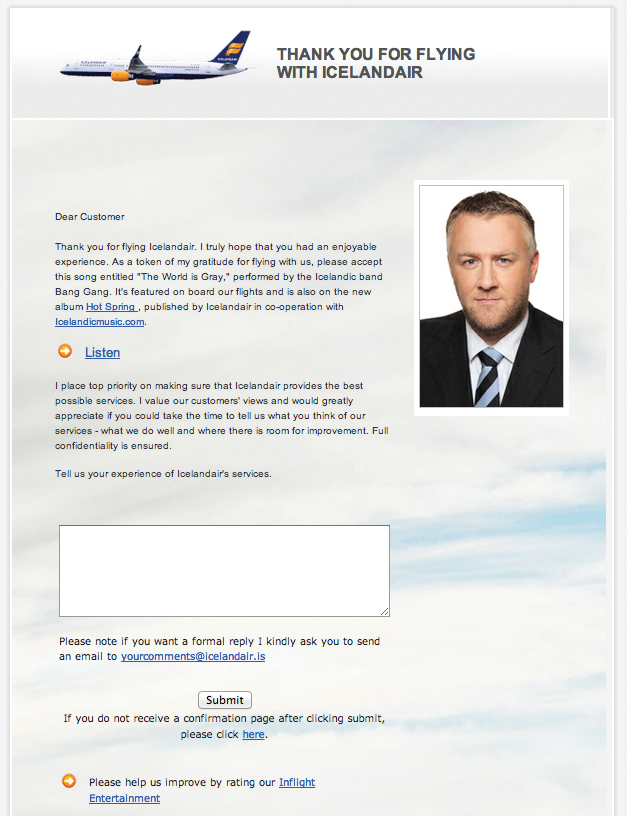

Icelandair uses a variation on foot-in-the-door by “giving” you a song to listen to in the hope that you’ll then reciprocate by taking the time to provide feedback. (icelandair.com site from a post-flight satisfaction e-mail)

By instead letting visitors see the large gains they get for providing just a small piece of information, the site has placed a foot-in-the-door, so that the door won’t be shut again. Now, when the site asks for a deeper level of involvement from its visitors, they will have seen the benefits and will be ready to reciprocate. Having already given a small piece of information will smooth their journey to full engagement with the site.

The step from no relationship to a simple relationship is much larger than any subsequent steps. After there’s an initial agreement, it’s easier to change the boundaries of the agreement because it would be cognitively dissonant for customers to go against what they first agreed to. Best compliance happens if customers think they’re committing to a worthy cause, or if they’ve already pictured themselves positively as part of the group you’ve invited them into.

- Make it easy for visitors to share a small piece of information with you, such as asking for a ZIP code to customize a weather forecast or calculate local sales taxes. This reduces the barrier to later sharing larger pieces of information.

- Escalate commitment gradually so that each individual step seems reasonable, and by the end, you’ll have a level of commitment that would have seemed totally unreasonable at the beginning.

- If some time has passed between asking for the initial information and a subsequent larger request, remind users that they already gave you the small favor. This will put them back in giving mode and make it harder for them to decline.

Reciprocation can also be used to guilt people into doing something for you. The urge to reciprocate is so strong that even if a request is blatantly unreasonable, individuals being asked will want to show that they are still compassionate and will therefore often be quite happy to perform a smaller task instead, as a form of apology for not agreeing to the larger request.

So, after expecting to have the door slammed in your face by asking for something audacious, knock again and this time ask for something much more reasonable—or at least reasonable compared to your first request. Now that you have set an anchor point, the smaller request will seem quite tame and achievable in comparison.

Robert Cialdini and his colleagues first described the setup required for successful door-in-the-face interactions in 1975. They ran an experiment where students at a university were approached in the hallways and asked to volunteer to council juvenile delinquents for 2 hours a week over a 2-year period. This is obviously a major commitment and was turned down by everyone who was approached. The requester would then ask whether they would be prepared to chaperone these same individuals on a 1-day zoo trip. Fifty percent of the time, the answer was yes. In comparison, when Cialdini’s team asked for the smaller favor without first presenting the larger request, the compliance rate was only 16.7 percent.

Cialdini emphasizes that it’s important to make the individual feel like they are making a reciprocal concession. There must be a large difference between the overly ambitious condition and the second more reasonable condition, and only a yes/no option for each condition. This is important because it’s necessary for individuals to first refuse the large request so that they feel obliged to reciprocate when they notice how much smaller the second request is, and the only way to do so is to say, “yes.”

It’s also important that the same person makes both the overambitious and the smaller requests, because otherwise the individual won’t feel the need to reciprocate with a concession of his own. To maximize compliance, the second request must also be a smaller version of the first one rather than new request.

Online examples are slightly harder to find because if the initial request is seen as just plain crazy, the back button is just one click away. The way to combat this is to show that you know it’s awkward and unusual to ask for the big thing, but to still ask for it anyway. By making it clear you understand the discomfort, customers will be less likely to use it as an excuse.

Door-in-the-face techniques can work in virtual worlds with avatars asking first for an unreasonable and then a more reasonable request, but what about on websites, where one of the key variables—the consistency of the individual making the request—is no longer visible?

The most apparent use of door-in-the-face is to get purchasers to register their information with a site. By presenting a sign-up form at the beginning of the process, but allowing site visitors to skip that registration process, it might make those same individuals more likely to agree to “saving” their shipping details (ostensibly the same information) at the end of the checkout process.

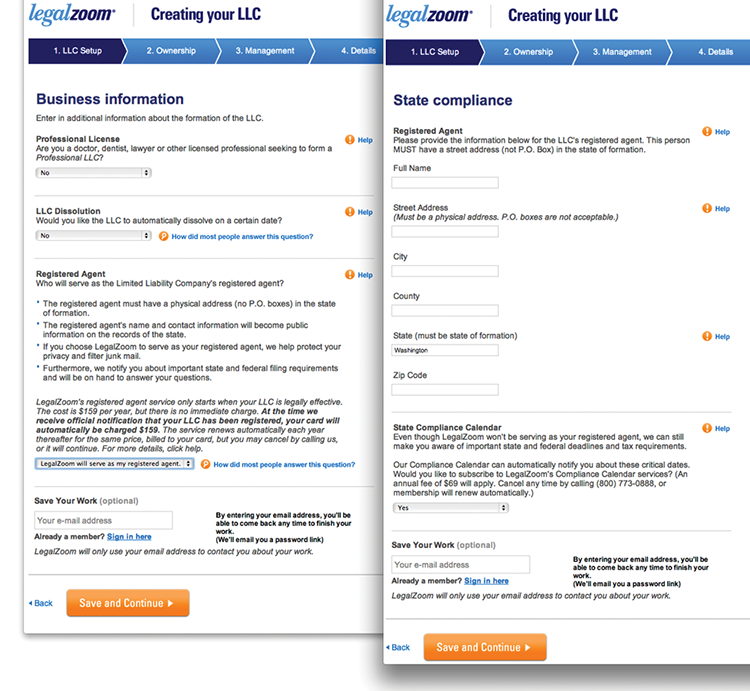

More subtle applications require a longer task flow, such as the one LegalZoom has to help business owners fill in the forms required to set up a business. Although it advertises the cost of an LLC filing as “from $99,” there are plenty of upsell opportunities within the flow. One is where LegalZoom offers to act as the company’s registered agent, for an annual fee of $160 (sensibly charged at a later date to avoid sticker shock). If you decide to forego this service, the next page of the form offers a notification service that reminds you of state compliance dates, for just $69/year.

Door-in-the-face works because you control the anchor—the initial unreasonable request—and so you control the level of contrast between that and the reasonable request that follows it. People aren’t good at making absolute decisions, but they can be quite good at making comparative decisions. In comparison to the unreasonable request, the reasonable request is relatively small. It’s also possible that people feel that by backing down, you have made a compromise on their behalf. As such, they now feel compelled to reciprocate for your compromise by agreeing to the smaller request.

LegalZoom.com offers online forms to help create business entities. It first offers a high-cost service option (left), but if that’s refused, on the next page it offers one that requires hardly any work on its behalf for a much more “reasonable” annual rate (right).

- Ask for a big commitment first, and then request a smaller thing if people refuse.

- Make it clear that you know it’s unusual/uncomfortable to ask for the big thing. By acknowledging this, you make it harder for people to refuse the smaller thing based on discomfort.

- Invoke reciprocity by showing that you’ve made a compromise in asking for the smaller thing.

- Make sure that you provide a clear funnel into the door-in-the-face process. When you present the unreasonable request, provide a No Thanks button that draws people in to the presentation of the reasonable request.

- Just occasionally people will actually agree to your initial unreasonable request. Be sure that this doesn’t catch you off guard, and that you have a way for people to actually sign up for your large request.

- Guilt most affects in-group members, so make it clear how much like your visitors you are (and what positive traits they have) as you make your request.

Sites used to require up-front registration before even letting users in to see or test out a service. Now, few use that model and instead are more likely to balance the need for up-front information with the need to show the product off through use.

This concept of delaying the request until it is in context has its roots in theories of reciprocity. Users feel obliged to respond (reciprocate) when given something. Even if the gift is small (such as free entry to a site), they will respond with valuable (to advertisers) personal information.

Users aren’t necessarily unreasonable in their value assessments; for example, they will give City, State, ZIP, Age, Gender (CSZAG) information to get access to a service that they want to use, reasoning that the obligatory ads that they will see would at least have some relevance. Also, not surprisingly, there is little requirement on users to make this data accurate as it is unlikely to impact service provision. For the longest time, the Hotmail e-mail service had an inordinate number of users who claimed to live in the Beverly Hills area. (Cultural reference: ZIP code 90210 was etched in many people’s minds thanks to a long running TV soap series.)

More unique and accurate information normally requires a higher value service in response. For instance, numbers (date of birth, phone number, house number, Social Security number, and credit card number) tend to have more perceived value to people than non-numerical data, probably because they are better identifiers or allow financial transactions to occur.

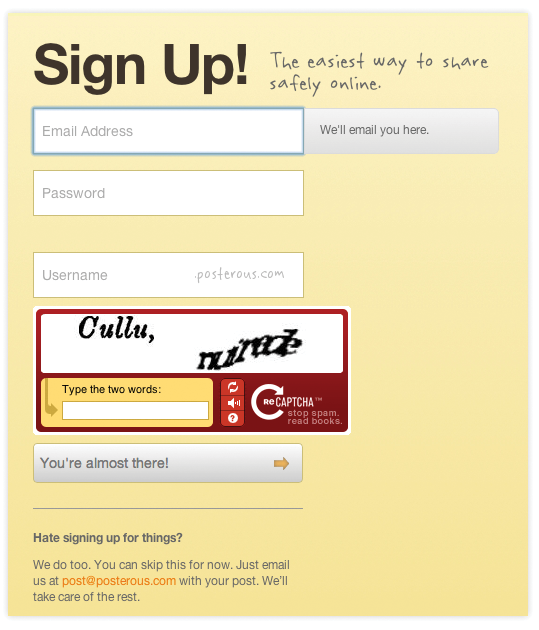

Posterous, a blog creation site, takes this concept to the extreme; you just e-mail content and it shows up as a blog in your name on its site. The company still asks for all the same information that other social media sites request, but it delays the request until it is in context: when users want to access more complex site functionality, or to keep some content private.

Posterous.com understands you don’t always want to give any information. Instead, at the bottom of the form it tells you that you can just e-mail content and it’ll start a blog for you. It subsequently deepens the relationship with you after you commit to using the platform.

This approach is especially important for services that require a network of users to function. WebEx’s online conference product does this well. New users can try out the service with absolutely no commitment if an existing user invites them. It’s only when they want to initiate a call that they need to sign up. They have to provide only the minimum of information until they want to do something more complex.

A corollary of this is not asking people to create accounts at your e-commerce site until after they’ve finished the checkout process. Here, it’s easy to remind them that they already trust you (they just bought something from you) and that they have already given you all their information. All they need to do to make it easier to check out next time is create a password. Whereas registration would have been seen as a burden, they are now willing to give you permission to store all their information as a service.

Leaving these questions until the user is invested means that they’re both more likely to trust the site and also more willing to give true information because they have spent time and effort to create the content they’ve added.

- Gather the minimum amount of information necessary to furnish the service.

- Prompt for additional information when visitors start using additional services. Justify the information request with reference to the additional value that users will get from the service.

- Always try to tie the requests to a reciprocal agreement (give me X so that I can give you Y) to ensure that the data is accurate rather than fake.

- If you’ve gathered information as part of a checkout or other process, offer to store it for later. That sounds like a time-saver rather than a burden or imposition.

- If you can’t provide enough value to elicit reciprocity, try the door-in-the-face strategy: Ask for a lot of information, and then settle for much less.

Invoking gluttony with scarcity and loss aversion

Imagine you are given a $1 bill. You hold it in your hand. Now you have the option to keep the money or to gamble it on a coin-toss where you can either win $2.50 or lose the dollar entirely. What do you do?

If you’re like most people, even when this task is repeated 20 times, you’ll still only gamble your $1 on 11 or 12 of the rounds. And if you do lose your $1 in one round, you’ll be much less likely to gamble in the next round. As the rounds progress, you’ll be less likely to gamble at all.

Now the thing is, it actually makes sense to gamble on every round. On average, each round where you gamble will net you $1.25 because you will win the coin toss one-half of the time.

So why don’t you follow this rational course? It seems that your emotions can get in the way of making logical decisions. This is especially true when the logical decision involves giving up something that you already have. In fact, it takes individuals who have brain damage that causes problems in processing emotions to perform more “sensibly” in this test.

Even though there is the potential to earn more money, there is also the potential to lose what you are already holding in your hand. The fear of losing what you already have (your loss aversion) is sometimes as much as twice as powerful as your desire to benefit from a potential gain.

Another powerful fear-based motivator is scarcity. By either creating a scarce thing (a title, award, or membership) or selling a scarce thing (where demand is greater than supply), you can count on people’s fear of missing out to ensure that they attribute more value to the item than it is actually worth.

Tom Sawyer got other kids to work for him because he convinced them that it was a scarce event (“Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?”) only open to select individuals with sufficient skill (“I reckon there ain't one boy in a thousand, maybe two thousand, that can do it the way it's got to be done”) and where demand was greater than supply (“If he hadn't run out of whitewash he would have bankrupted every boy in the village”). Tom pushed all the right buttons that turn scarcity into desire.

You can use these elements of scarcity—infrequency, exclusivity, and competition—to appeal to people’s natural gluttonous tendencies.

Often it is sufficient to manufacture the feeling of scarcity without actually limiting supplies. For instance, the sentence “If operators are busy, please try again” has much more social proof than the sentence “Operators are standing by to take your calls” because it implies high demand for the item being sold.

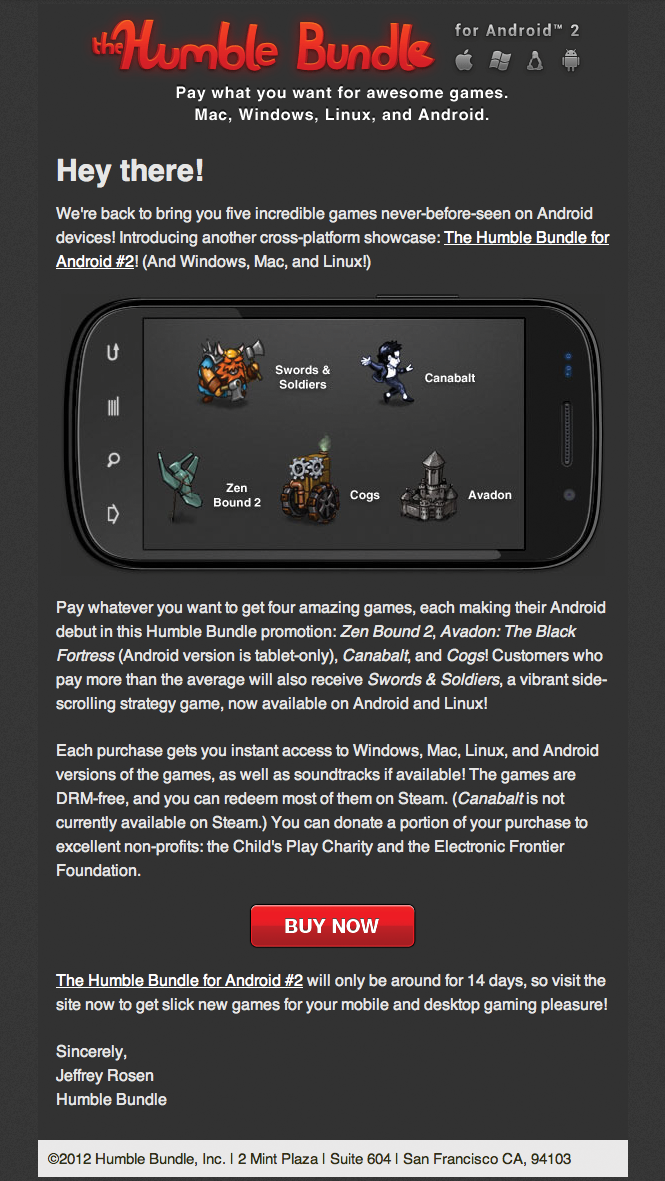

You can also create scarcity by limiting the time that something is available. The Humble Bundle games offers bring a set of well-liked independent computer games together into a pay-what-you-like deal, but only for a 2-week period.

Even though the games have normally been released for some time before the bundle is introduced, the fact that they are offered together at a low price (you pay what you want), with bonus extras, and with a proportion of proceeds going to charity, makes them a great deal.

Even if you hadn’t been planning on purchasing all the games, or if you had already purchased one of them at full price, this limited-time offer provides a good incentive to get the whole bundle while the games are cheaper than they would otherwise be. This is a form of loss aversion that applies even before people have the product in hand. Paying full price for one of the games is now a “loss” in comparison to purchasing it as part of this bundle.

The addition of bonus extras such as the game soundtracks and “making of” documentaries provide exclusivity. Often the bundle is the only time that these items are made available.

The Humble Bundle includes the added element of competition because to get the bonus extras that come with the bundle, purchasers must pay more than the current average price. This means that as more people purchase the bundle, the average price rises. Thus, it pays to be one of the first if you want a bargain.

Humble Bundle’s offers invoke scarcity by being a limited time offer and competition by gradually increasing the price required to unlock the exclusive bonus extras. (humblebundle.com)

- Include the three elements of scarcity to ensure people want your product:

- Infrequency: Make it clear that the offer or event is only available for a limited time.

- Exclusivity: Promote items that only certain people will qualify for (even if the qualification criteria are as loose as “has a pulse”).

- Competition: Show that there are others who are also interested in the scarce resource.

In 1990, John Gummer, the Agriculture Minister for the UK Government, needed to keep people eating beef. Public fears about mad cow disease had increased after several types of beef offal were banned in the UK. Sales of beef products were falling.

His solution was to instill doubt in the minds of people who thought that beef was bad. His method was to feed a beef burger to his 4-year-old daughter, Cordelia, at a well-publicized media event held at a boat show in his constituency. After all, who could believe that beef was unsafe if a public figure with direct responsibility for public food safety was prepared to feed it to a 4-year-old girl?

The real master-stroke was to use burgers, a form of beef that almost everyone could identify with and would be unhappy to give up (nearly 50 billion are eaten annually in the United States—three per person per week). Showing Cordelia enjoying her burger triggered loss aversion and simultaneously reinforced that beef was safe.

This was near the beginning of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) scare that would later lead to 4.4 million cows in the UK being slaughtered and more than 200 human deaths from a variant of Creutzfeld-Jakob disease caused by eating meat from cows that had contracted BSE.

John Gummer “enjoying” a burger with his daughter, Cordelia. Who could possibly doubt his intentions? © Press Association

It later turned out that Mr. Gummer knew of the dangers but was scared of the economic outcome if the news spread. He was thus prepared to risk his daughter’s health for political gain. This act didn’t seem to hurt his political career, as he is now a life peer in the House of Lords. However, he did leave a legacy because now when other politicians try similar PR tactics in the UK, it’s described as “doing a Gummer.”

You too can instill doubt to prevent people from canceling subscriptions or memberships. You simply need to tap in to the natural loss aversion that people will feel when they are reminded of what they have in their hands and what they’ll lose as a result of their actions.

One way to do this is to start people’s membership with a certain level of service included free of charge. Subsequent fear of losing this “free” level of service means they’ll pay more to keep it than they would have paid to obtain it in the first place.

Obviously, after people start using a service, they also create data and artifacts (photos, documents, contacts, and so on) that are tied to the service. Any time that customers attempt to cancel their membership can also reinforce just what they’ll lose. Even when companies such as Google offer migration of data so that there’s less to lose, there’s still a lot tied up in social capital (friends and colleagues with whom the data is shared) that can’t necessarily be replicated elsewhere. Instilling doubt in these situations simply involves pointing out what people might lose by closing their account or migrating their data. Trying to deactivate your Facebook account brings up a series of photos from friends’ accounts that show you with those friends. Each has the caption “so-and-so will miss you” and invites you to send them a message. Obviously sending them a message takes you away from the deactivation page and back into the loving embrace of the site.

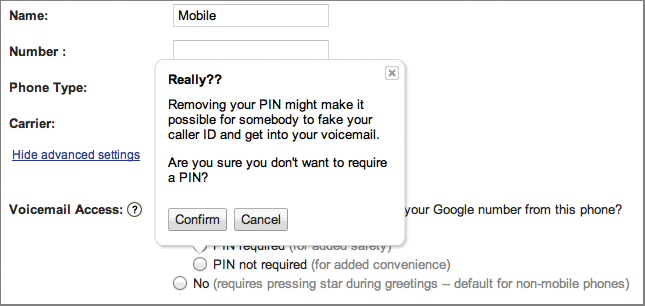

Companies don’t need to reserve this tactic just for serious situations such as account closure. They can instill doubt to get people to choose an option that they prefer. Again, Google is a master of this. In Google Voice, for instance, choosing particular settings leads to a prompt designed specifically to instill doubt in customers’ minds. The option is still available, but because Google (rightfully) doesn’t recommend it, it makes users think twice and feel bad for selecting this option over the “safer” alternatives.

Google Voice settings can have unexpected side effects. This dialog instills doubt by presenting a scary scenario to make users think twice before choosing the risky option.

All of these situations work by framing the doubt in terms of what people may lose by choosing the undesired option. Although that’s a double negative, it has more power than reminding people of what they might gain by choosing the desired option. People feel loss more powerfully than gain, so it’s easier to manipulate them through doubt about negative outcomes. The magic of loss aversion will do all the rest.

- Loss aversion is strongest when people have recently experienced the benefits of the product or service. If customers are canceling after a period of inactivity, find a way to convince them to use the product again (for instance by offering a free month of service, or access to a premium feature) so that they will feel the loss more keenly.

- At select points in your product, remind users of what they might lose by not choosing your preferred option. Be subtle, but remember to phrase in terms of loss.

- Save fear tactics for high-stakes interactions. People don’t like being scared on a regular basis, and the effect is diminished with over-use.

- On cancellation forms, invoke loss aversion by asking, “Which of these features will you miss the most?” This may be sufficient to pull customers back from the brink, and it’s still useful information to know regardless of the outcome.

Fear of losing out disproportionately influences people’s value judgments. Forcing people to act fast also changes the way they make decisions. They tend to become more conservative, preferring less risky options and paying more attention to negative information.

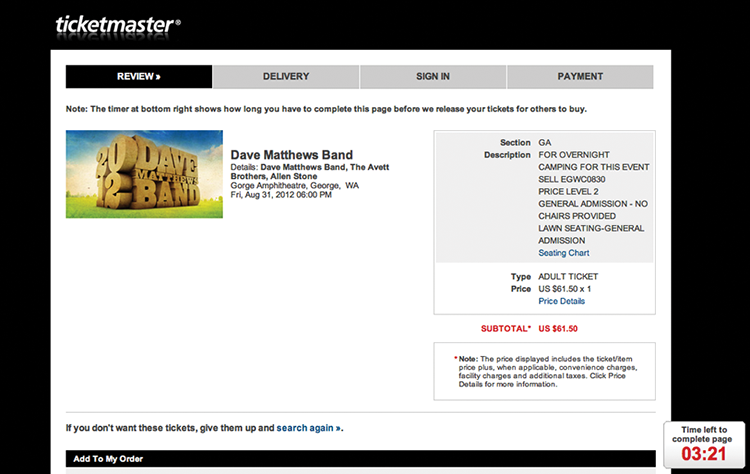

Putting those two facts together creates a powerful force that companies like Ticketmaster have learned how to harness.

Ticketmaster gives customers a limited amount of time to make a purchase. This is ostensibly to prevent individuals from “holding” tickets for a show without actually paying for them. It has the additional effect of creating an environment where customers are forced to act quickly to secure the tickets they want, especially when Ticketmaster has a virtual monopoly on ticket sales for many venues.

The Ticketmaster interface induces panic because it is timed. Coupled with loss aversion, this makes it easy for Ticketmaster to get customers to agree to things they otherwise may not. (ticketmaster.com)

The time constraint induces a kind of panic. Fear of losing out on the tickets leads people to try and complete the process as quickly as possible. They are therefore less likely to pay attention to details, and more likely to do whatever it takes to get through the process unhindered.

Each page in the checkout process has a highly visible countdown timer. This serves as a constant reminder that the tickets could “disappear” if you don’t act fast. Acting fast means skipping over apparently inconsequential information and acting to reduce risk where possible. The outcome of this type of urgency is that customers will be less likely to change default selections (the highest price tickets), more likely to choose fast and secure shipping options (at a higher cost) and less likely to question the additional “convenience fees” that are added by the company.

An interesting side effect of adding time constraints is that it enhances people’s commitment to completing challenges, but only for low-complexity tasks. Giving people task-completion aids that let them follow rules by rote increases their performance on these time-constrained tasks.

This makes you wonder what would happen if Ticketmaster started offering a robo-booking option—just choose “best seat” or “cheapest seat” and let the site do the rest (for a fee). This feature might be especially attractive for people who had been caught out by the time-constraint issues previously.

- Place a time constraint on a task to push people toward less-risky options and to accept the default selections.

- Add a task-completion aid that does not require analytical thinking. It should list simple rules for people to follow to complete the task.

- Offer to bypass the time-constrained task by providing an automated output with the default settings. You may even charge more for this “convenience.”

Self-control: Gluttony’s nemesis

Gluttony is a failure of self-control. Once we have made a small lapse, a larger one becomes much easier. A small nibble of chocolate while on a diet doesn’t satisfy our craving. Instead it makes subsequent bingeing much more likely. Similarly, when companies try to persuade individuals to do something, a small immediate concession can lead to a much larger one later. Self-control tends to break down when we focus more on emotional impulses than on rational thought. We know rationally that we shouldn’t eat the chocolate, but emotionally it just feels so good.

Psychological research into self-regulation failure suggests that there are several ways in which people misuse or fail to use their self-control.

First, over-optimism leads people to miscalculate their likelihood of success, so they continue with tasks long after they should have quit. Making people work for a reward is one way for companies to take advantage of this. Once customers have attributed a personal value to a reward, they will work harder for it than they rationally should. The same is true when companies provide seemingly tiny rewards. The value justifications that people create in their own minds lead them to false assumptions about the ultimate value of the payout they will receive. Perhaps the simplest self-regulation failure caused by false assumptions is people’s inability or unwillingness to do some simple sums when faced with what appears to be a fabulous bargain in penny auctions. Here, even though people know the deal must be too good to be true, they will continue anyway in the over-optimistic hope that there will be a pleasant outcome.

Self-regulation failure also happens because we sometimes think we can control things that really aren’t under our control. This is true for both companies and consumers. When a company is hacked it is by definition not in control of the situation, yet many act as if they still are. Failure to behave honestly and show the true problems can create real trust issues. Customers are definitely not in control when they are drawn in with the lure of scarcity, especially when there is a deadline for acquiring the scarce thing. By manipulating availability, exclusivity and competition companies make consumers panic. That emotional response suppresses rational thought and so removes self-control.

The third area of self-regulation failure comes from focusing on the emotional outcome rather than the cause of the problem. This can lead to impulsive behavior, which people subsequently regret and which in turn leads to a worse emotional outcome. One example of this is reciprocating when we logically shouldn’t. Foot-in-the-door and door-in-the-face techniques rely on people’s emotional feeling of commitment, leading them to reciprocate even when they know that they would never agree to perform that same task outside the implicit contract that has just been created.

There is however some hope. People who are made to think about the payoffs of self-control are less likely to subsequently lose control. A real-life example of this is the apparent calming effect that social media have had on unruly spring break behavior. Typically, spring break is a time for college students to unwind and have fun. Traditionally that has tended to involve large quantities of alcohol and alcohol-induced behavior. However, anecdotal reports suggest that since the advent of sites such as Facebook, which document every moment of people’s lives, spring breakers have tended to become better behaved, aware that photos of their behavior will be posted online for friends, family, and future employers to see.