Pride

Humility makes men like angels; Pride turns angels into devils.

Saint Augustine

Pride isn’t the sin it used to be. In the 4th Century, Evagrius of Pontus claimed that pride was the primary sin among the seven, and the one from which all others stemmed. By the time of Thomas Aquinas in the 13th Century, it was seen in a more measured manner—some pride was acceptable, but a surfeit was still a sin. In the 21st century, with the advent of social media, it appears that we more often ask, “Have you no pride?” when confronted with yet more drunken party photos, as if pride is a positive attribute that arbitrates in matters of taste.

These days, the sense in which pride is bad is probably best summed up by the word hubris—arrogance, loss of touch with reality, overestimating one’s capabilities, thinking that you can do no wrong. In the Greek tragedies, hubris leads the hero to pick a fight with the gods and thus be punished with death for his insolence. These days, it’s called overextending your credit.

Of course, the aim in this book isn’t to bemoan the lack of humility in modern society but to see how sites leverage this human weakness.

Misplaced pride causes cognitive dissonance

Harold Camping, the owner of familyradio.com, has been wrong a couple of times in the past. He predicted that the world would end on May 21, 1988—then again on September 7, 1994, and subsequently on May 21, 2011, before settling for October 21, 2011. After the world steadfastly refused to stop turning on each of these dates, you’d think that Harold would call it quits and stop believing that the Rapture was imminent. You’d also think that the large number of his followers who sold or gave away all their possessions or spent their life savings on advertisements for the event(s) would be embarrassed or upset. Although a small minority expressed disappointment each time, most continued to believe Harold. Why?

It’s all about how the brain manages to rationalize or resolve two conflicting concepts: a state called cognitive dissonance. For example, people know that smoking kills, but they continue to smoke. These dissonant thoughts don’t work well together. People resolve the issue by removing one of the two conflicting concepts. Quitting tobacco is much harder than rationalizing that smoking is unlikely to kill you because you are a healthy individual, and anyway, everyone dies of something. In other words, changing your opinion (that smoking can kill you) is much easier than changing your behavior (smoking). So the dissonance is resolved by rationalizing your opinions, even if that leaves you believing something strange.

In Harold’s case, each time he could demonstrate how his calculations (based on interpretation of scripture) had been slightly wrong. By admitting a small personal failing, he managed to refocus his followers’ actions around the new date. For his followers, it was much easier to accept that their leader had forgotten to add a couple of years in his equation than to believe that their Rapture-targeted behaviors were misaligned or even laughable. The deeper they were involved in Harold’s prophecies, the more pride they had at stake, the more cognitive dissonance they had to resolve, and so the more likely they would be to grasp on to any explanation that Harold could provide.

However, after his October 21, 2011 prophecy, Harold stopped providing new dates and seemed to be somewhat chastened.

The question constantly arises, where do we go from here? Many of us expected the Lord’s return a few months ago, and obviously we are still here. Family Radio is still operating. What should be our thinking now? What is God teaching us? In our Bible study over the past few years, we came to the conclusion that May 21 and October 21 were very important dates in the Biblical calendar. We now believe God led us to those dates, but did not give us complete understanding. In fact, we did not understand at all the correct significance of those two dates. We are waiting upon the Lord, and in His mercy He may give us understanding in the future regarding the significance of those two dates.

Maybe this new outlook is partially due to his award of the 2011 Ig Nobel mathematics prize (jointly with several other prophets) for “teaching the world to be careful when making mathematical assumptions and calculations.”

Online, cognitive dissonance can be brought about by effects such as buyer’s remorse, in which the purchaser struggles to justify the high purchase price and their desire for an item in comparison to their subsequent feelings of the item’s worth.

Sites help users resolve this cognitive dissonance by giving them reasons and evidence that bolster their satisfaction with the product (positive reviews; images of famous people using the product; and promises of hard-to-quantify benefits, such as social approval brought about by using the product) rather than letting them resolve the dissonance by returning the product.

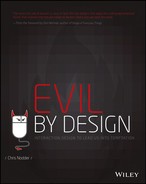

The Best Made Company sells axes. One of its models was exhibited by the Saatchi Gallery in London, instantly turning it from a utilitarian object into a work of art. Painting stripes on the handle in limited numbers per design added to the exclusivity and thus desirability (see also the Tom Sawyer effect, in the chapter on Gluttony).

Lowes is a hardware company that also sell axes. At Lowes, a similar hickory handled felling axe costs $30. The $30 option comes with a lifetime guarantee, so why would you choose the $300 version? Mainly because Best Made offers many superlatives that help to ease cognitive dissonance. Its product description reads more like a manifesto to the outdoors lifestyle than a listing of features.

If you were to point out to owners of this axe that they’d just paid about ten times too much money for something used to chop wood, they would have plenty of ammunition to fire back. Clever marketing on the bestmadeco.com site turns a utilitarian purchase into a search for exclusive art, thus resetting customers’ pricing expectations. Continuing the marketing message through to the packaging of the item ensures that it is reinforced when customers receive the goods and every time they look at the product subsequently.

Buyer’s remorse: You can spend $300 or you can spend $30. In both cases you get a hickory handled felling axe. (left image: bestmadeco.com, right image: lowes.com)

To prevent buyer’s remorse, get customers to imagine the experiences they’ll have with your product or the way that others will react when they see the customer using your product. Take the customer in their mind’s eye to a contented future with the product and then make them look back on the current time as a pivotal decision point.

Continuing with the axe example, consider this quote on the About Us page: “Best Made Company is dedicated to equipping customers with quality tools and dependable information that they can use and pass down for generations. We seek to empower people to get outside, use their hands and in doing so embark on a life of fulfilling projects and lasting experiences.” These words are aimed at making you jump into the future and look back on now. How could you not buy something that promises a fulfilling life full of lasting experiences?

To resolve buyer’s remorse if it still happens, the trick is not to hide the return path, but to make it easier for customers to resolve the dissonance by changing their opinions instead. Because people are biased to see their choices as correct (see the description of confirmation bias in the Change Opinions pattern that follows), any supporting evidence can reinforce the initial opinions that led them to choose your product, help them rationalize their decision, and thus leave them happier with their initial choice. It is therefore important to use the same style of messaging throughout the site, from product pages through to the support and warranty/returns sections, and on all other collateral such as documentation sent with the product.

- Give purchasers plenty of reasons to want your product. Provide testimonials, reviews, and lifestyle images. Help them visualize a rosy future that includes your product. This is just as important after the purchase as before. Don’t have a glossy sales page and a dull support page. Make it clear to existing owners that they did the right thing.

- Add something cheap but unique to your product offering. Best Made place their axe in a wooden crate lined with “wood wool” (shavings). This costs them comparatively little but boosts the appeal of the product by giving owners self-reassuring evidence that they received something special.

- Hire good product packaging and site designers. Presentation—how the product looks—can determine its price point. Utilitarian or bohemian?

Social proof: Using messages from friends to make it personal and emotional

Pride means caring what friends think about us and our activities. We’re proud when our friends praise us for something we’ve done, and upset if our friends disapprove. Much of our behavior is determined by our impressions of what is the correct thing to do. Our impressions are based on what we observe others doing.

Those others don’t have to be our friends. In a new situation we may follow the cues of total strangers. Most of those strangers could also be new to the environment, but we still make the assumption that they have a deeper understanding of the situation. Experts, celebrities, existing customers, and even the “wisdom of the crowd” can all serve as drivers for how we behave. This influence is known as social proof: “If other people are doing it, it must be right.”

If we see a tip jar full of bills, we are more likely to tip. If we see a nightclub with a line outside, we’re more likely to think it’s a popular venue. If we see a restaurant full of happy people, we’re more likely to think that eating a meal there would be worthwhile. That’s why baristas “prime” their tip jars in cafes, why nightclubs keep a slow-moving line outside even if the club is quiet inside, and why restaurants seat people at the window seats first thing in the evening.

It doesn’t hurt Apple to have long lines outside its stores on product release days. (Well, except for the Chinese release of the iPhone 4S, in which there was such a large crowd that the police made the stores cancel the release.) This just provides additional social proof that Apple’s products must be worth having because so many people line up to buy them.

The line outside the Chicago Apple store on a cold morning two weeks after white iPads were first released. The fact that people were prepared to stand outside at least half an hour before opening time for the vague possibility that this store had some iPads in stock projects strong social proof that Apple’s products must be worth having.

In 1969, Stanley Milgram was running studies looking at conformity. He’s best known for a study in which he determined that subjects would give supposedly lethal shocks to another person if told to by an authority figure. However, he also ran slightly more benign studies that looked at how influence varies with different numbers of sources. He had a paid helper stand on a busy sidewalk and look up at the (empty) sky. He noted that approximately 40 percent of people passing would also look up. With two confederates, that number rose to 60 percent. When he paid four people to stand together and look up, around 80 percent of people passing would also look up.

If more people are doing something, it lends additional credibility to the activity. If you hear about the same product from several different sources, you tend to attribute more positive views to it than a product you were unfamiliar with. In other words, familiarity doesn’t breed contempt, it breeds reassurance.

Showing what others bought and what is frequently bought together serves as two additional social proof reinforcements for the item on the page. (amazon.com)

People rely on social proof more when they are unsure what to do. New users, people shopping for infrequent or unfamiliar purchases, or people seeking expertise are all likely candidates for social proof persuasion.

To give customers several converging statements that add to social proof, sites also provide white papers of case studies, indications of how popular a particular item is (number sold, number left in stock, or even a “sold out” label), recommendations for complementary products or accessories, and product reviews.

Testimonials are another type of social proof. If you offer testimonials, make sure they come from people who appear qualified to make the statements, and that you give enough details about these people so that a reader can validate that they exist.

Because the information from each of these sources complements the other sources, and because they appear in different places around the site, users tend not to notice that the same basic message is repeated to them in different ways each time.

It’s important that the social proof examples you use guide people in the direction that you want. Making it clear that a large group of people engage in the behavior you don’t want (even if you emphasize it only to say “don’t do this”) legitimizes that behavior in people’s minds and may provide social proof in the wrong direction. For instance, a campaign against teen drinking that tries to shock by saying what proportion of teens drink may work for adults, but will have the opposite effect on teens. (“Hey—all the others are doing it, so why don’t I?”)

The best forms of social proof come from outside the direct sphere of influence that a site has. Reading positive statements about a product or company on a supposedly neutral third-party site can have greater social proof outcomes than reading the same statements on the company’s site. By 2011, only 13 percent of consumers purchased products without first using the Internet to review them. More customers think it’s important to get reviews from other consumers than from professional reviewers or consumer associations.

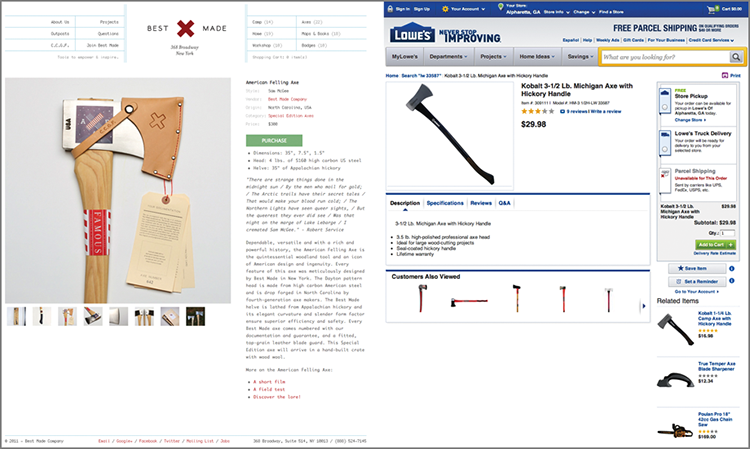

This has led to the rapid growth of pay-to-blog advertising and sponsored posts. Companies exist to match advertisers with bloggers (inblogads.com, weblogsinc.com, sponsoredreviews.com, reviewme.com, payperpost.com, and blogsvertise.com), and a whole army of bloggers exists to take advantage of these paid endorsements. Many are in the home, family, and parenting blog categories and on tech “review” sites.

LinkWorth is just one of many companies who match advertisers to bloggers. The pseudo-originality of the blog post—each one written by a different blogger, but on the same theme—increases search engine optimization and adds social proof. (linkworth.com)

The proliferation of for-pay blogging caused concern about both the impartiality of reviews written online and also the blurry line between commercial sites and blogs that were basically shills for an organization.

In 2009 this led the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to update its testimonial and endorsement guidelines for the first time since 1980.

When there exists a connection between the endorser and the seller of the advertised product [that] might materially affect the weight or credibility of the endorsement (i.e., the connection is not reasonably expected by the audience) such connection must be fully disclosed.

The maximum fine is $11,000—although this seems to be aimed more at celebrities on talk shows than at mommy bloggers. Now the industry has several different yet similar codes of conduct, all aimed at allowing bloggers to receive money from advertisers for giving honest opinions. The money hasn’t disappeared, but the honesty (and the fact that blog posts are sponsored) should be more apparent.

The fact that bloggers can leave less favorable reviews probably won’t even harm sponsors considerably. Only 4 percent of people would change their mind about a product or service after reading one negative review, and it takes three negative reviews before the majority of users would change their minds. The proportion of reviews can also play a role: Three negative reviews may mean very little in comparison to 300 positive reviews.

- Try to create several statements that back up the same general positive concept about your product or service. Users are more likely to believe you if they hear several variations on the same theme.

- Get statements placed on different sources or sites. Seemingly impartial reviewers have more credibility, and hearing the same statement from multiple sources also improves social proof.

- Place statements at locations on the site where they’ll be seen by new users, people shopping for infrequent or unfamiliar purchases, or people seeking expertise.

- Describe your process, product, and so on as the accepted norm—for instance, the industry standard or reference item. Being seen as a standard gives the product implied social proof.

- Work with common stereotypes of behavior—if it’s commonly held that people will do X in situation Y, then reinforce that stereotype to your advantage, as it plays to social proof.

- Use site statistics to impute social proof—for instance “70 percent of our business comes from client referrals” demonstrates that clients like the business enough to recommend it to others.

- Make sure the social proof example you use emphasizes your desired behavior rather than trying to dissuade people from the opposite behavior. Don’t even raise the opposite behavior as an option.

To reach Hanakapiai Beach on Kauai in the Hawaiian islands, you have to hike a couple of miles along the beautiful but up-and-down Kalalau trail along the Na Pali coast. The visual reward makes the hike worthwhile, and it would be unfair to spoil it for you by showing you photos here. Instead, I’m going to show you photos of the warning signs that you see just before you reach the beach.

On the left is the series of three official signs. Each is carefully crafted to give a depiction of the dangers that await you, backed up by stern sounding warnings. That clean, official, indirect voice keeps things passive and impersonal and thus relatively easy to ignore.

On the right is the unofficial sign, found just a few yards further down the trail. Obviously hand-carved by a concerned amateur, this sign talks less about the natural features of the beach and more about the outcome: “Killed? Yikes!” This more personal approach (backed up with near real-time updates on the death toll) is much more likely to hit home with passing hikers.

Back in the tech world, Jimmy Wales’ “personal appeal” to raise funds for Wikipedia has a positive effect on donations. Wikipedia runs annual fund raising drives, and in 2011 the banner ads it used to accompany the fund raising were crafted through a series of A/B comparison tests to ensure maximum click through, followed by appeal pages designed to tell a story that would maximize conversion and donation amounts.

Wikipedia’s A/B tests allowed them to work out that the most effective messages came from Jimmy Wales (the founder and public face of Wikipedia) and included a trustable explanation as to why the donations were needed. Thus, it came as close to being “personal” as is possible from a person that donors had probably never met.

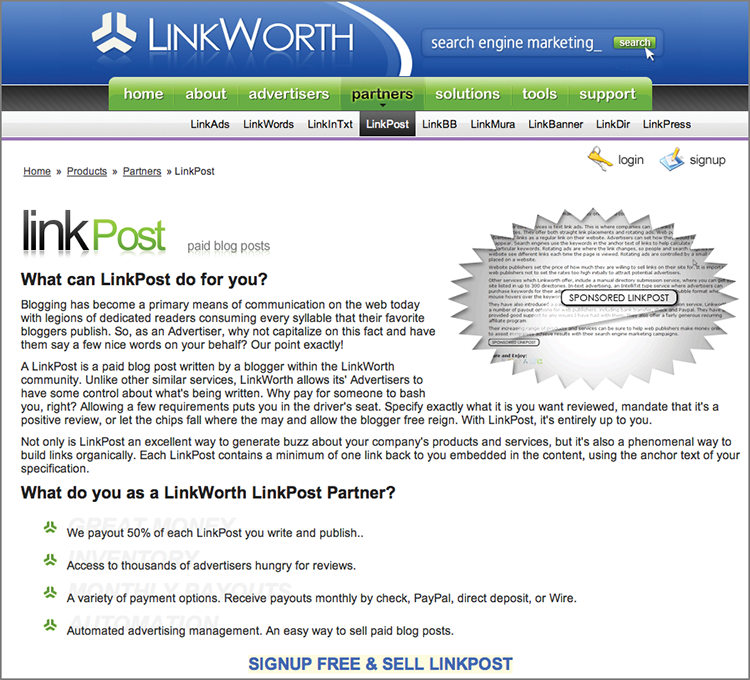

Social networking sites use pseudo-personal messages in an attempt to drive viral adoption. For instance, Google+ tells you your friends have invited you, so you feel like it’s a recommendation from them to use the service. All that actually happened was that your friend added your e-mail address to their Google+ Circles.

Did Chris really invite me to join him? No, he just added me to his circles. But it sounds more like a recommendation this way.

After you sign up and add some people to your own circles, you perpetuate the social proof effect. In addition, when you reciprocate with an “add,” Google informs the person who first added you that “they want to hear from you.”

The recipients of my “invitation” now apparently want to hear from me. Wow, I’d better start using the service more diligently!

Even more insidious is LinkedIn and Facebook’s habit of using your name and likeness in ads seen by your friends and contacts saying that YOU recommended/used/did this thing, so your contacts should, too.

An e-mail from LinkedIn uses my connections’ names and likenesses to convince me to do something. If all of these respectable professionals are doing it, maybe I should be too.

Interestingly, Facebook first tried this in 2007 with its Beacon product. It bombed because it was hideously intrusive, to the point of sharing details of purchases that individuals made at third-party sites on their Facebook walls. After much public outcry it was shut down in 2009.

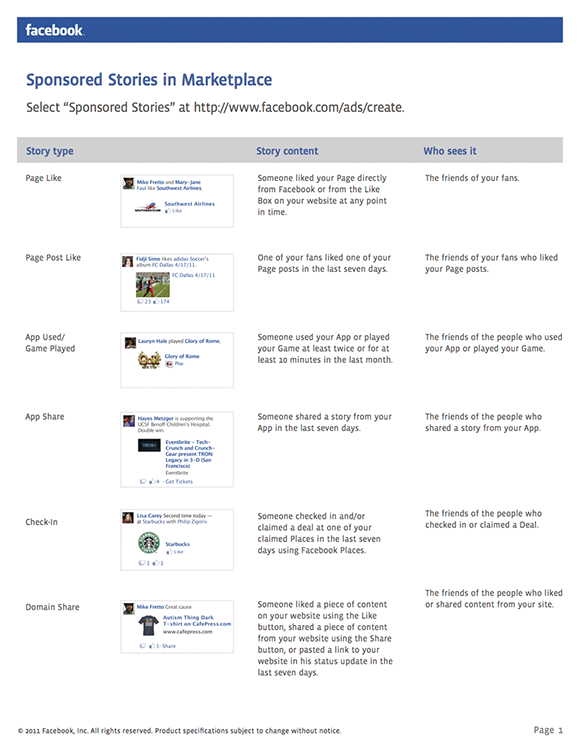

Facebook’s demonstration of how advertisers on their site can take advantage of social proof to place adverts in the news feed by piggybacking on your friend’s posts

Now, Facebook has launched a similar feature called Sponsored Stories. If friends use the name of a company or product in a post that they make, or “Like” a company elsewhere on the web, this feature shows the logo or other advertising visuals for that company or product attached to the friends’ posts, called out in the right column among other ads, in the ticker, and more recently in the news feed. The main difference in functionality and presentation this second time is that the feature works much more like a social proof than a broad spam.

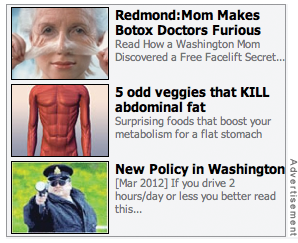

The more similar the subjects of the social proof are to you, the more likely you are to respond favorably. That’s why the social media implementations work so well—the social proof is provided by people within your network. However, even a weak form of social proof can be sufficient to tip the balance. You may have noticed online advertisements for car insurance, work-from-home schemes, or mortgages that highlight how someone in your neighborhood has saved money, earned millions, or otherwise improved their life. Obviously all they are doing is geolocating your IP address, but the end result is a marginally more convincing advertisement.

Even weak forms of social proof can be effective. Advertisers wouldn’t pay the extra money to customize advertisements based on the approximate location of your Internet connection unless there was some payback for them.

Will users call you out for using social proof? No. Most individuals—even when told about social proof—claim that other people’s behavior doesn’t influence their own. So they don’t believe that they will fall for these tricks even while they are falling for them.

- Prime users to do what you want by showing how other people have already done that thing.

- Make sure that these “other people” share characteristics with your users so that users identify with them as much as possible. Using someone’s friends or contact list has additional influential power.

- If it’s likely to benefit you, show what other people did in a similar situation. Case study white papers, Amazon.com’s “people who viewed this also viewed these” and “n percent ended up buying…” widgets are good examples.

- Encourage Likes and +1s, comments, retweets, and responses to your social media activity. The social proof provided by a large number of recommendations can be highly convincing.

- Social proof works best if the social group used as the proof closely matches the current user. Use your users’ profile information to craft a story that matches their needs well.

New year’s resolutions are hard to keep: 22 percent of people fail after one week, 40 percent after one month, and 81 percent after two years. Quitting smoking, reducing alcohol consumption, and losing weight are all hard to do.

Although the only tried-and-true method to lose 10 pounds in 48 hours is food poisoning, companies like Weight Watchers know that the social element—regular meetings where you “weigh in” and share your progress with others—are big drivers for successful weight loss and long-term weight maintenance. The key here is the shared commitment that you make to reach your goal. By meeting with and sharing encouragement with others in a similar position, it becomes easier to stick to your plans.

Getting that commitment is one thing. Sharing it with others is even more powerful. Now the user faces social reprobation if they don’t follow through. This could be as simple as adding the user’s name to a wall of commitments, or e-mailing the referrer of the user to say they’ve signed up. Commitment to a goal is much more concrete if the commitment is written down.

Many sites and apps exist to assist you with your efforts. One big motivational technique that several of the sites use is to replicate the social element by making your goals public. This way, people in your social network can see your planned and actual workouts, and leave encouraging comments for you. Runkeeper, Fitocracy, Fleetly, and MapMyRun/MapMyRide all have publicly accessible pages for each user and optional sharing via other social media such as Facebook and Twitter.

The GymPact site and iPhone app allow you to set goals (“pacts”), put money (“stakes”) against them, and then check in to the location to verify that you attended. People on average miss 10 percent of their commitment days. When this happens, they have stakes deducted from their account. That money goes to reward people who did attend. (gympact.com)

HabitForge, 21habit, and GymPact take a different tack: A third party (the site or app) holds you to your commitment. 21habit and GymPact even include a financial incentive. With 21habit you pay the site up front, and then on each day that you complete your activity you get to reclaim your day’s dollar. Skip a day, and your money goes to charity. Even though this might at first seem like a straight contract between the individual and the site, the act of telling the site (and subsequently being reminded on a daily basis) makes the activity external—public, rather than internal—private.

- Persuade your users to give you access to post to their social media accounts. You probably don’t have to be deceptive: If you have done a good job of selling the product or service, then it should be easy to explain how a public commitment can make the user more likely to follow through.

- Create an environment such as a forum where users can form groups with a shared commitment to performing an activity that you care about. Peer pressure can keep the group more committed.

- Display a simple metric of “success” that shows at a glance whether users are progressing toward their stated goals. This metric should be easily interpretable by users and by their extended social network. Allow users to “share” this metric as a widget on other sites to gather even more public commitment.

- Combine public commitment with an affiliate program. This gives users more motivation to share because they make money from the process of expressing their commitment.

Changing your opinion on something involves admitting that you were wrong. The more public your initial statements, the more pride you must swallow in moving to the new perspective.

This is so deeply ingrained that we even have a tendency to search out and interpret information in a way that confirms our current beliefs. More interestingly, after we find sufficient information, we stop. We don’t tend to seek out information that might prove us wrong. This is known as confirmation bias.

Clever sites that need to sell people on an idea that involves making them change their minds do it by giving users selective information that confirms their preconceptions while also supporting the concepts that the site wants to get across.

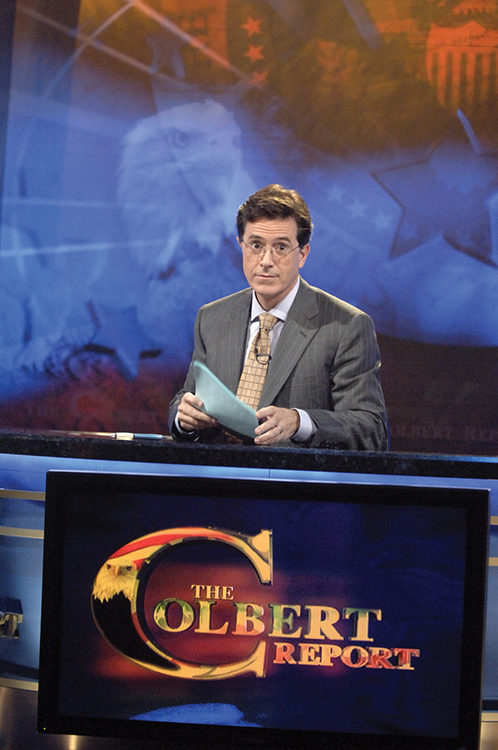

This is easier to achieve than you may think. Stephen Colbert hosts a late-night comedy show in the persona of an outraged Republican, while actually satirizing right-wing policies. Or maybe I only think he does. According to a study run by researchers at Ohio State University, viewers with right-wing tendencies still find the show funny. “Conservatives were more likely to report that Colbert only pretends to be joking and genuinely meant what he said, while liberals were more likely to report that Colbert used satire and was not serious when offering political statements.”

Colbert’s response when asked about his political leanings was “I have no problems with Republicans, just with Republican policies.” By creating parodies of these Republican policies, Colbert could be seen as using Republican-held beliefs to change Republicans’ perceptions.

Stephen Colbert: Funny to both sides of the political divide, despite parodying Republican philosophies (Photo: Joel Jefferies from Comedy Central site)

Online, there are few better examples of changing people’s opinions by expressing similarities than DivaCup. This company discusses a generally taboo topic (menstruation) and changes women’s minds about abandoning traditional practices (tampons and pads) and trying something that at first glance seems like it couldn’t work (an insertable silicone cup). It achieves this by first co-opting the audience into agreeing that yes, they have experienced the issues that the site lists, and then going on to show how the DivaCup solution is similar-to-but-better-than what the audience is currently doing. This then allows them to emphasize the positive elements of the product that people couldn’t disagree with wanting (clean, hygienic, comfortable, green, and so on).

DivaCup’s “have you ever…” section gets women thinking about situations that are similar to their lives. (divacup.com)

- Don’t try to persuade people that they should change. Instead, show them how they are already doing elements of what you want them to do.

- Emphasize the positive and the similar elements rather than requiring them to think about the negative and the unfamiliar aspects.

- Talk in general terms that can be interpreted positively by any user. “Family values” is a positive term to everyone who hears it, regardless of how they interpret it.

- Talk about aspirations. “Yes, I do want to lose weight/find a partner/make tons of money/…”—people feel motivated to achieve their aspirations even if they never actually work toward them.

In 2002, I was a user researcher at Microsoft, working on the newly announced Trustworthy Computing initiative. I was testing user comprehension of security features that would subsequently make their way into Windows XP and Windows Vista. Some of the prototypes that we used for our studies needed a trust certification logo. The designer, Angela, made up a credible-looking logo just so that we had something on the screen for the usability tests. Much to our surprise, users expressed great trust in the fake logo despite never having seen it before and never having heard of the (imaginary) certifying company.

In 2006, John Lazarchik, VP of eCommerce at Petco.com heard that a third-party security icon, when used on a home page, could improve the rate of conversion from browsers to buyers. The team ran some tests that involved displaying a security logo on the home page and on subsequent pages of the Petco.com site. Using 50–50 split A/B testing, Petco found that it could increase conversions by 1.76 percent just by adding the icon at the bottom right of the page, way below the fold. Moving the icon to the top left just below the search box gave an 8.83 percent increase in conversions. This is a massive jump in sales for a tiny piece of screen real estate—much smaller than the space taken up by an advertisement.

What makes us trust these logos? All take the form of an endorsement. The endorsement is a type of social proof, even if it originates from the site itself.

Why is it that users express trust in a logo for an imaginary company? What is it about a certification image that reassures them sufficiently to be more likely to spend money on a site? Luckily, it’s all about perception rather than reality. B.J. Fogg, founder of the Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab, lists four elements to website credibility. They are: presumed credibility (assumptions made by the user), surface credibility (first impressions of the site), reputed credibility (third-party endorsements), and earned credibility (built over time).

Trust logos fall into two of these credibility categories. Surface credibility is provided in part by a professional looking certification image with words such as “guarantee” or “certified” on it. For images provided by third parties, the certification is an endorsement of the site, which is a type of reputed credibility.

Obviously these certification images are often little more than paid endorsements—getting someone else to sing the site’s praises or just showing membership of an arbitration service like the Better Business Bureau (BBB). However, even paying for someone else’s positive remarks sounds more credible than the site’s own commentary.

It turns out that although they work well to increase the perception of trust, neither of these elements are necessarily good indicators of Fogg’s fourth credibility category: earned credibility. Ben Edelman, a Harvard economics researcher, discovered that typically the sites displaying trust certifications are actually significantly less trustworthy than those that forego certification. Using MacAfee's SiteAdvisor tool to compare almost 1,000 TRUSTe certified sites with more than 500,000 noncertified websites, Edelman discovered that "TRUSTe-certified sites are more than twice as likely to be untrustworthy as uncertified sites."

However, perception seems to be more important than reality in this situation. Petco no longer uses the “Hacker Safe” logo from 2006, but they have replaced that security certification with two new “trustmarks”: a McAfee antivirus message at top right and a Bizrate “customer certified” icon at bottom right. These certificates both theoretically denote earned credibility (the Bizrate icon is only available to sites with a certain level of customer satisfaction), but the aim is probably still financial. The McAfee antivirus site boasts that sites displaying its “SECURE trustmark have seen an average 12% increase in sales conversions.”

Although it may not mean much in real terms, certification raises the credibility of the site marginally above that of its competitors in the eyes of visitors. In an environment in which users are unsure who they can trust, they’ll take whatever they can find. That marginal level of additional reassurance may be all it takes to sway someone toward using the certified site instead of other similar destinations.

- Find certification authorities that you can sign up for. Options might be the Better Business Bureau, SSL certificates via your site host or domain registrar, TRUSTe certification of your privacy policy, and ratings and review companies such as Bizrate, antivirus companies, or industry accreditation programs.

- Be sure that your certification image addresses your users’ concerns. Are they most worried about viruses? Your returns policy? Their credit card number’s security? Talk to this fear in the certificate you display.

- Place the certification images wisely. Only use them at places during the interaction where users are likely to be looking for additional reassurance. Using them on every page might make them blend into the background too much and wastes space that could be used for other purposes.

- Consider making up your own certificate, perhaps to advertise your site’s guarantee. The guarantee doesn’t have to be anything special, but having a logo makes it look impressive.

Closure: The appeal of completeness and desire for order

How would you describe the following image?

Most people would immediately say “A circle,” despite the fact that there is a distinct gap in the shape, and it’s actually more like a rotated capital “C” than a circle. It seems that our brains are designed in a way that favors clean, unambiguous outcomes, so we often describe items that are more ambiguous using these unambiguous terms.

In psychology, this is known as closure: people’s “Desire for a firm solution rather than enduring ambiguity.” The feeling of ambiguity or uncertainty puts people on edge. It is only when they have reached their goal or found a solution that people can feel comfortable setting the thing aside. The feeling of completeness that accompanies closure puts people at ease. Oftentimes people will deceive themselves by mentally “completing the circle” in order to reach this state of happiness rather than remaining in ambiguity.

This desire also manifests itself as a social pressure. Pride is predicated on being orderly and complete rather than sloppy and half-finished. There are ways to leverage closure online. They mainly focus on encouraging people to strive for completeness by achieving certain subgoals or collecting items until they have a full set.

Foursquare is a location-based social media site that allows people to “check in” at locations to unlock badges. Checking in at the same location on a frequent basis may be enough to make an individual the “mayor” of that place. Although it could be seen as a game, the compulsion to keep collecting badges and to remain as the mayor of a location definitely don’t harm sales at the retail locations, restaurants, and cafes that people check in to.

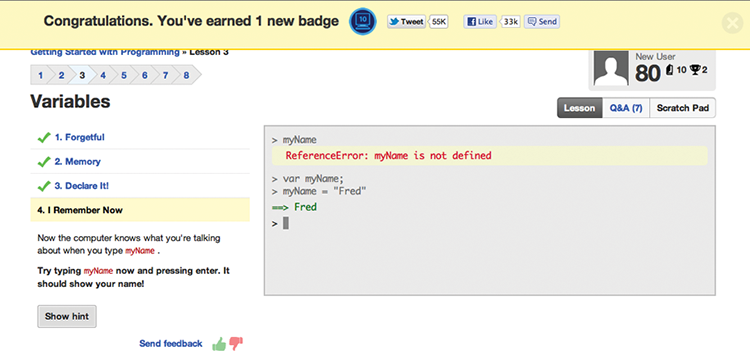

Codecademy does a similar thing in a learning environment. The online learning site teaches visitors to write JavaScript code. Again, it uses achievements in the form of points and badges to first encourage visitors to register, and then to encourage registered users to continue completing coding exercises and assignments. As part of Code Year (an initiative to encourage more people to become code-literate in 2012), almost 400,000 people took part in a weekly coding challenge.

Codecademy.com encourages you to learn to program by awarding points and unlocking achievement badges (top). By showing you what you’ve already earned in your first session (bottom) they can encourage a sense of ownership that makes you more likely to register with the site, even though the badges have no real “value.”

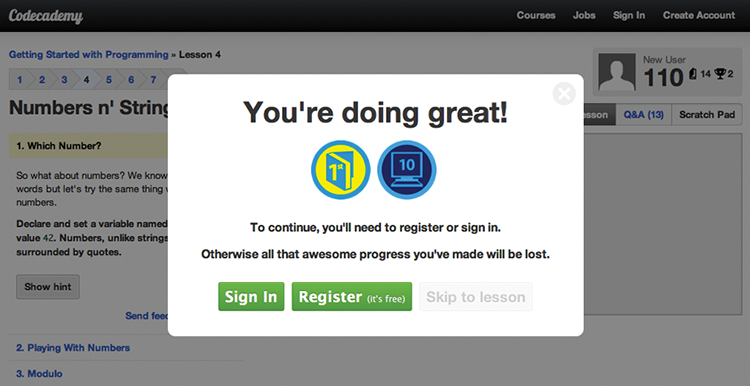

Sites that rely on user-generated content also need mechanisms for encouraging contributions. Question askers will come to a site that actively answers questions; the trick is to reward the answer providers. Reward comes in the form of “points” for answering questions.

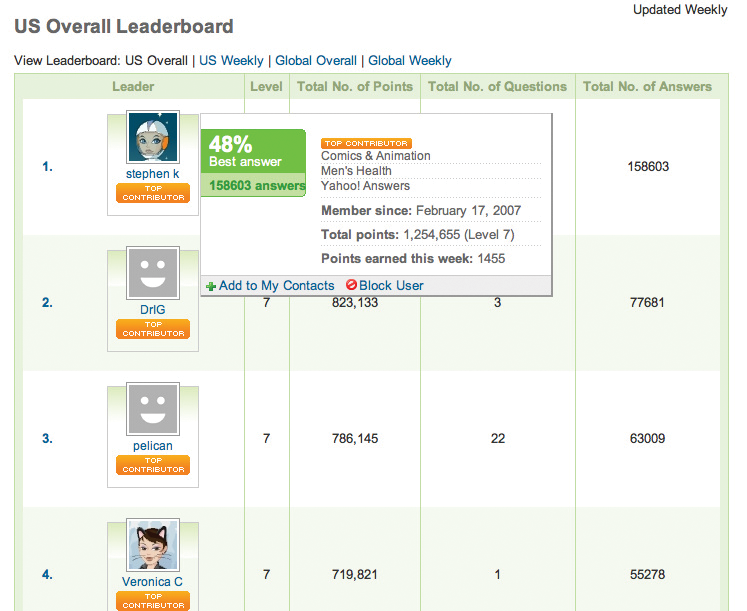

Yahoo! Answers is a crowdsourced knowledge base, which relies on user contributions to create both the questions and the answers. (answers.yahoo.com)

Sites like Yahoo! Answers have found that the reward doesn’t even have to be financial. Some people will participate just for the status they achieve by providing the best answer to questions.

Stephen K had answered almost 160,000 questions in just under five years. That is almost four questions per hour, every hour, every day, over that period. There is no physical redemption for these points. They are merely a status symbol. (answers.yahoo.com)

Obviously, online games such as World of Warcraft also encourage closure through leveling up and collection of in-game items, but the real trick lies in turning nongame tasks into a type of game (often referred to as gamification).

Cow Clicker is the ultimate abstraction of this mechanism to its basic elements. Ian Bogost, a professor at Georgia Tech, created the Cow Clicker game within Facebook as a form of social commentary on gamification, the social gaming genre (of which he is not a fan) and the reward culture that it engenders.

You get a cow. You can click it. In six hours, you can click it again. Clicking earns you clicks. You can buy custom "premium" cows through micropayments (the Cow Clicker currency is called "Mooney"), and you can buy your way out of the time delay by spending mooney. You can publish feed stories about clicking your cow, and you can click friends' cow clicks in their feed stories. Cow Clicker is a Facebook game distilled to its essence.

Cow Clicker: The game in which you click cows, send status updates about clicking cows, and buy new cows to click on using Mooney. The nine empty spaces around your cow are filled with friends’ cows through pasture invites (viral awareness raising). The lack of purpose is the game’s purpose. (Image from bogost.com)

If this doesn’t make much sense to you, you probably aren’t a Farmville, Castleville, or Cityville fan. These games, all living inside Facebook and all created by one company, Zynga, combined to produce 12 percent of Facebook’s revenue in 2011. That’s $445 million funded entirely by Facebook users clicking on things.

Obviously these games have slightly more content than Cow Clicker, but to Ian Bogost’s point, they are fundamentally designed to get users to click on things, and to worry about those things sufficiently that they come back and click some more, time and time again.

An added twist is that users can reduce their level of worry (about whether their crops need watering, their cows need milking, and so on) by paying for in-game items to make their lives easier. Earning points to buy these items is theoretically possible in-game (with LOTS of clicks) but is much more easily achieved by buying points (see also the pattern “Move from money to tokens,” in the chapter on Greed) or completing “offers” that give points in exchange for purchasing items from advertisers’ sites.

- Give people some achievements early in their interaction so that they get used to the concept.

- Show them the empty slots that they need to fill with more achievements.

- Provide levels of membership, with achievements to gain extra points, and potentially more benefits to reaching each level. Benefits may include the ability to do more of something that you want people to do anyway, such as moderate a forum.

- Turn it into a game, or at least give ways to game the interface. You can earn bonus points for making it look like the “gaming” is in some way illicit and thus create groups committed to maximizing their potential gains (such as the online coupon communities).

- Give users ways to progress through paying rather than through working for it. Examples are using Mooney in the Cow Clicker game, or the secondary market in World of Warcraft where you can buy anything from gold to pre-experienced game characters.

Dan Lockton studies how design in the physical world can encourage certain behaviors. He demonstrates how desire for order can be used to make people perform tasks in the physical world. The following pictures show a light switch in its on position (left) and off position (right). Users of the switch can only achieve closure by turning off the light, thereby saving energy.

This light switch just cries out to be “aligned,” which then turns off the associated light. It was created to demonstrate easy ways in which people can be encouraged to save power. It is part of the AWARE project, by Loove Broms and Karin Ehrnberger at the Interactive Institute in Stockholm.

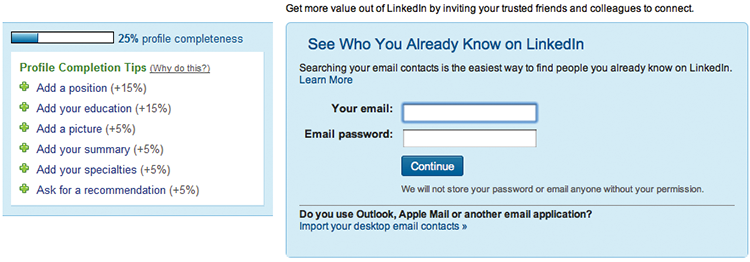

Social networking sites such as LinkedIn need your data to create the connections that make a useful network. However, it normally takes a bit of convincing to get users to do something as personal as sharing an address book. To add encouragement, LinkedIn uses language that makes it clear that you are currently in a disorderly state. Claiming “your profile is 25% complete” creates enough disharmony to convince people to hand over their e-mail address book, add more connections, and start recommending others in the network.

LinkedIn profile completeness—why WOULDN’T I give them access to my e-mail so that I can be 100 percent complete?

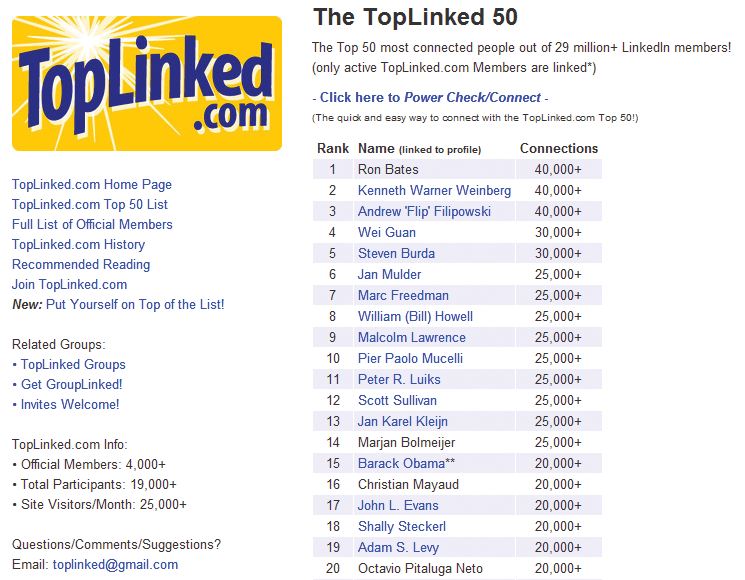

Making it clear that you have a small number of connections in comparison to other individuals provides the motivation to start “collecting” more contacts. If you think this is silly, explain the existence of sites such as TopLinked.com, which provide a way to quickly grow your social networks (through “open networking”), for the small recurring fee of $10/month. This turns social networking from a useful linking of like-minded individuals into a lowest common denominator competition fuelled by pride.

TopLinked.com encourages “open networking,” appealing to contact collectors everywhere.

TopLinked used to run a high-score table listing the LinkedIn members with the most connections. Back in 2008, several celebrities were near the top of the list.

Yes, #15 on this list of the "TopLinked people on all of LinkedIn" is the real senator and possible future President of the United States of America, Barack Obama! He has not officially signed up as a TopLinked.com Member (probably because he is currently rather busy running for office), but, as his campaign message is about inclusiveness and bringing people together, we know we can continue to count on him to be welcoming of TopLinked.com people who wish to help him further expand his LinkedIn network. … The real key question though is whether he can make it to the Top Spot on this list! :-)

TopLinked.com, 2008

This again appealed to users’ competitive nature but was completely counter to LinkedIn’s mission to create a “professional network of trusted contacts.” LinkedIn claims that “Connecting to someone on LinkedIn implies that you know them well” and that makes business sense. LinkedIn makes its money from analyzing the connected nature of individuals to determine their traits and target advertising. If the connections are random, there is no money to be made. It also makes money from upselling users on premium features such as wider searches (beyond third-level connections) and the ability to send “InMails” to people outside their network. Again, if an individual has a massive network, this reduces the need for these services. Steven Burda, a highly linked individual, claims he can reach 97 percent of LinkedIn members via his third-level connections.

When LinkedIn changed users’ profiles to show a generic label of “500+ Connections” rather than a true figure, TopLinked could no longer maintain its leader board. Instead, it had the clever idea to allow people to buy Top Supporter points (again on a monthly recurring subscription). The person who purchases the most Top Supporter Points each month gets to the top of the Top Supporter List.

This Top Supporter List has no credibility outside the TopLinked site. It no longer reflects the member’s position within the LinkedIn community or has any relationship to their actual number of contacts. However, it is still a list, and there is still a way for people to get themselves to the top of the list, by purchasing more Top Supporter Points. Surprisingly, that is all that it takes for people to want to take part.

Recruiters and salespeople seem to figure frequently in the TopLinked Top Supporter List. Open networking may be a way to scrape more names to spam with job openings, but it’s a shotgun approach that values quantity over quality and so appeals to the bottom feeders in the industry. Sad as it is to feel that you need to pay to have friends, especially if most of those friends are as freaky as you are, there are obviously people out there who are prepared to fork over cash for this type of completeness.

- Show users the disorder associated with their account. Give them easy ways to resolve the disorder into harmony.

- Create a sense of progression by providing a set of logical steps toward order.

- Show gaps where data is missing—if possible make these gaps public to shame users into completing the empty pieces.

- Reward tidiness. Give users more access, power, points, or whatever other unit of currency you use as they complete more of the actions you want.

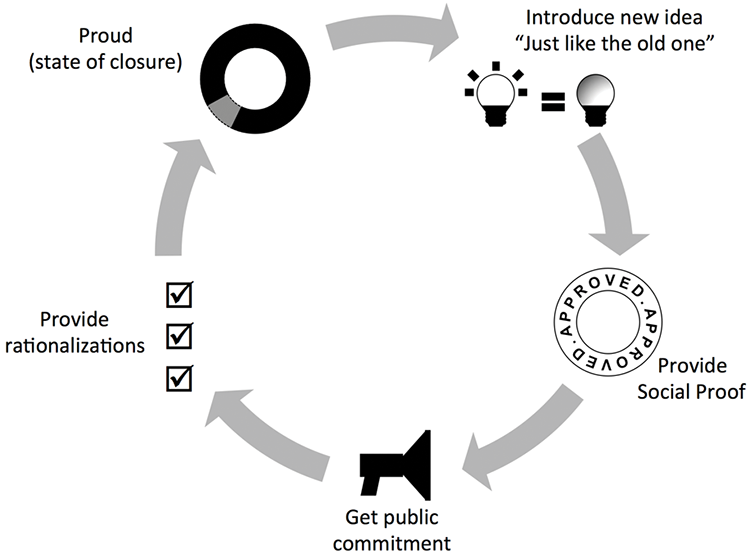

Manipulating pride to change beliefs

Society has an ambivalent attitude to pride. As we mentioned in the introduction there are different levels of pride. Pride in our appearance or in our abilities (self-esteem) is acceptable, so long as it doesn’t lead to vanity. But too much pride causes people to enter into hubris, where they become stuck in their ways, sure their current practices and beliefs are right.

Trying to change the decisions that led people to their current state is hard. Any new concept that you introduce that differs from their existing knowledge will create cognitive dissonance. People don’t like being forced to consider two competing ideas because that keeps them out of the state of closure that they desire. It doesn’t help that the people who most feel a need for closure tend to also have attitudes associated with dogmatism, a need for order, and conservatism.

So people will have a tendency to ignore or rationalize away the newly introduced concept. Resolving the dissonance this way allows them to carry on with their beliefs, however strange this makes their reasons seem to others.

Getting stuck in a certain mindset—inertia—causes people to act in certain ways that you can either seek to leverage or to overcome.

To leverage the inertia, you can provide supporting reasons to prevent buyers’ remorse, and to help remove any trace of cognitive dissonance. Hearing the same message repeated many times from different sources or seeing many other people behaving the same way (social proof) gives added weight to someone’s decision. This is especially true if friends or members of the same group provide the social proof. The social proof provides credibility, which is especially useful to help people justify infrequent or unfamiliar purchases.

Complete the loop by first introducing change in a subtle way, and then helping people justify their new behaviors. Once they get to the point of publicly admitting their new stance, you can set that behavior and create closure once again.

Social proof is also useful when you want to start overcoming inertia and get people to make a change. Because the need for closure is associated with conservatism, a good appeal is through subtle changes in behavior led by example. For instance you can show how someone’s friends are doing this new thing, and demonstrate how the new thing is similar to the old way they currently use. Highlighting the general similarities between two views helps to ease people across to the new perspective.

It is important to provide confidence that your proposed new way of doing things is acceptable. Appealing to people’s need for order by using images of certification provides credibility that is itself a form of social proof.

If you can get people to make a public commitment to the new approach, it means they can no longer back down. The public commitment might set off more cognitive dissonance, but now, because they have openly aligned themselves with the new approach, the dissonant belief that will be expelled is the old one.

At this point, the individual will start to rationalize their new behaviors. Now you are back in the position of wanting to leverage inertia again. You can assist by providing reasons that allow the individual to keep their self-esteem intact, and by showing social proof for the new behaviors. The individual whose mindset you just changed will be a willing participant in this process. They will tend to be selective in what data they look for and believe. Because they are now trying to remove cognitive dissonance in favor of the new idea that you introduced, they will seek out reviews, certification, and other social proof that supports that viewpoint in order to reach closure once again.