Anger

Anger as soon as fed is dead—

'Tis starving makes it fat.

Emily Dickinson

Anger is fear with a focus: an understanding of what caused the fear and often also the capacity to resolve the fear by acting to remove it.

It’s an active emotion; people want to deal with the cause of their anger in ways they don’t with other emotions. This happens on an intellectual and also a physical level, with biological changes as a result of feeling anger. However, just because people have the capacity to deal with the anger doesn’t mean they necessarily will. Anger often leads to brooding and plotting. Dante called it “love of justice perverted to revenge and spite.” That, in a nutshell, is what turns it from a virtue into a vice.

What causes anger? Typically, anger is caused by a negative event that someone or something else is responsible for. If we were responsible we would experience shame or guilt instead. If the cause were unknown, we would experience fear or anxiety. But if we have a target cause of the negative event, we feel anger.

Anger has different effects on judgment and decision making than do other negative emotions. Anger influences how we perceive, reason, and choose. Its effects spill over from the initial cause to other things we’re doing, affecting how we respond to situations that have no bearing on the thing that initially made us angry.

Anger can be a difficult emotion to harness. When we look back on instances when we were angry, we tend to think of them as unpleasant and unrewarding. However, while we are in the angry state, prior to resolution, the feelings we experience can be pleasant and even rewarding. In the right contexts, anger can be a highly motivating force.

Avoiding anger

When there’s a possibility that a company’s actions will create an angry response, there are two possible reactions. The company can either embrace the anger and try to shape it to its own ends or alternatively can try to minimize the anger by diffusing or displacing it.

As previously mentioned, anger without a definite cause becomes anxiety, and anger with a self-created cause becomes guilt, so one way of displacing anger is to shift the blame to someone else or back to the customer. This doesn’t necessarily provide resolution, but it does change the target from an external to an internal source. One problem with this approach is that blaming customers isn’t necessarily a good way to gain repeat business—especially blaming angry customers.

Instead, it’s better to attempt to avoid the anger in the first place. Here, we discuss three patterns that can enable companies to get what they want without creating anger in their customer base.

Relax all the muscles in your face. Now, tighten the muscles above your eyes that bring your eyebrows toward your upper eyelids and at the same time tighten the muscle that attaches your cheekbones to the corners of your lips (otherwise known as “smiling”). Are you feeling happier? Paul Ekman found that even getting people to consciously form their facial muscles into a certain expression could trigger the physical sensations of the corresponding emotion.

Using humor online can be challenging at the best of times because it is so easy to misread, but if you are sure the message is clear, it might be worth using a technique that gets a little grin out of somebody to help prevent them from becoming truly angry.

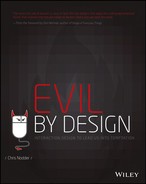

One thing that’s almost guaranteed to infuriate people online is when the service they are trying to use is unavailable. For a while in 2011, Tumblr.com used fan art created by Matthew Inman (TheOatmeal.com) on its server error page after a grassroots campaign by Inman’s blog readers. Tumblr is an image-based blogging platform. Because it isn’t likely to be seen as a mission-critical service, a humorous error page is likely to diffuse any anger before it starts.

Tumbeasts loose in the server room can cause no end of problems. (Tumblr.com 503 message created by Matthew Inman, theoatmeal.com) © Matthew Inman, The Oatmeal. (theoatmeal.com) CC BY 3.0

It’s worth pointing out that the tone of your humor is also important. Cartoons depicting hostile humor (one character putting down another character, for instance) could actually contribute to rather than reduce anger and aggression.

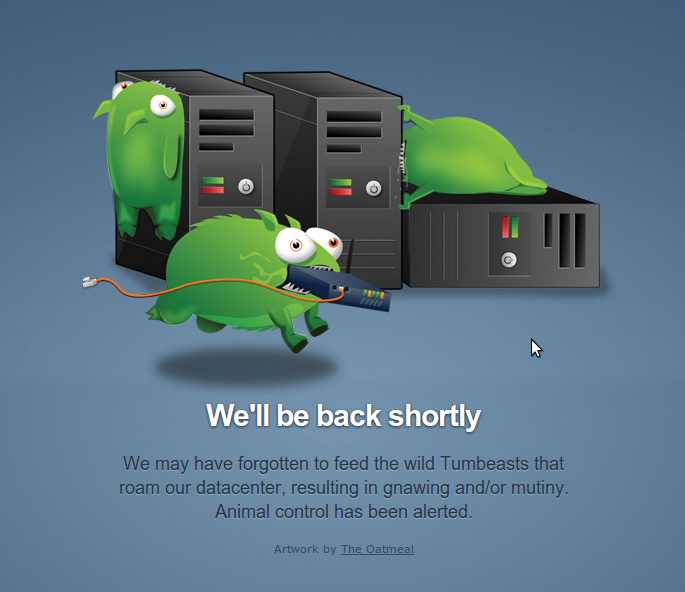

There are sites and situations where using humor would not be appropriate. Mozy is an online backup service. It uses a light-hearted and somewhat humorous tone across its site, potentially in an attempt to make backing up data seem less daunting. However, applying this to its error page is probably not a good idea. The result of an error on a data backup site is more serious than on a photo blog. Unfortunately, a couple of Mozy’s error messages start with a humorous tone saying, “Whoops!” Considering that at the point when they see this information people are already likely to be a little angry or upset, this approach is more likely to fuel anger than alleviate it.

Mozy.com makes its business from backing up customers’ data. How would you feel if you were in Mozy’s server room and heard somebody say, “Whoops!”?

The context of customers’ interaction with Mozy means that if they see an error on the system, they are more likely to be angry and need to have that anger addressed by providing ways to solve their problem rather than resorting to deflection, which would be more appropriate for a lighter-hearted or entertainment-driven product.

Humor also won’t cover persistent errors. Twitter’s equivalent to the tumbeasts is its Fail Whale image. Unfortunately, in Twitter’s early days the Fail Whale appeared so frequently that the visual gag lost its humorous aspect. That, coupled with Twitter’s move from novelty to more serious communication platform, meant that humor became a less suitable style of response.

- Use humor to reduce the potential for anger, but not to deal with existing anger.

- The humor you use should be whimsical rather than containing hostile or aggressive themes, such as one person putting down another person, because these can increase aggressive feelings.

- Jokes are only funny once. Ensure that people aren’t going to see the humorous content too many times; otherwise, its effect will wear off and may even backfire.

- If you know that users are likely to be angry at the time they see your response, consider a placatory approach instead of a humorous approach. Apply the punch-in-the-face test: Ask yourself whether using humor would get you hit if you were face to face with your user at this point.

Netflix wants to get out of the physical DVD rental business by converting all its users to online streaming customers. Although both businesses are profitable, it costs Netflix a lot more to service the mail order DVDs than to let users stream digitized content over the Internet. As of October 2011, Netflix streaming accounted for almost one-third of downstream Internet bandwidth in North America. That is more than all HTTP (website) traffic combined.

In July 2011, Netflix announced a price increase from $10 to $16/month for the combination streaming-and-physical service in an attempt to make the $8 streaming-only option seem more appealing. The price change alone caused a measurable issue: Approximately 1 million of the company’s 25 million subscribers canceled within the same business quarter that the changes went into effect.

This price increase was quickly followed in September 2011 by the announcement of a split into two separate companies: Netflix for online streaming rentals and Qwikster for physical DVD rentals by mail—each priced at $8/month. This was just too much change for both consumers and for the press. As Jason Gilbert at the Huffington Post wrote:

In its month of existence, Qwikster did nothing but foster ill will toward Netflix. The assumed purpose of the split—to enable Netflix to focus its resources and energy on acquiring streaming content and to phase out the less profitable, less popular DVD-by-mail service—was never well articulated. Qwikster was pitched, in a blog post and accompanying video, as a way to offer users more convenience, though the entire concept of Qwikster seemed anything but: Netflix was all but forcing its 12 million customers with joint streaming-DVD accounts to create two accounts, at two different domain names, with two credit card statements and two different sets of ratings and preferences, all on a new website run by a guy who couldn't even spell the word "quick" correctly.

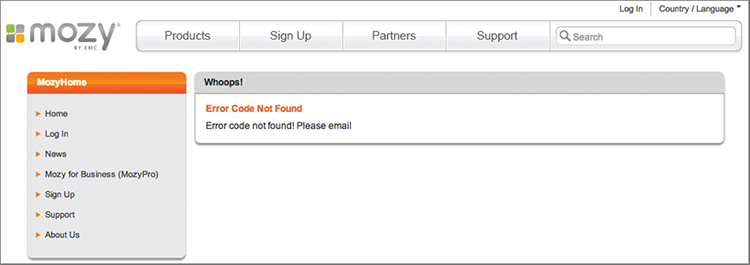

To its credit, Netflix realized (helped in part no doubt by plunging stock prices) that it messed up. Reed Hastings, the CEO, said, "There is a difference between moving quickly—which Netflix has done very well for years—and moving too fast, which is what we did in this case." It canceled the break-up plans and made a short, sweet announcement to its customers.

Although it’s clear that Netflix’ plans failed for several reasons, increasing both the financial and the physical burden on customers, even it admitted that it introduced changes too quickly.

People hate change. They love consistency. The posh name for this is status quo bias: the tendency to like things to stay relatively the same, and to perceive any change from the current situation as a loss. Loss aversion leads people to over-estimate the potential losses from a change and under-estimate the potential gains. They also tend to over-value their current situation (the endowment effect). The combinatory outcome of these behaviors is to stick with their current option. People will also stick with their current option if they feel that they have less information about their potential choices. Making people more knowledgeable about or even just giving them increased exposure to their other choices can reduce status quo bias.

Netflix’ admission that its plans went too far. An apology without apologizing. (e-mail from Netflix)

This is all, of course, predicated on the new choices being truly as good as or better than the current option. If the new choices would make people worse off, as in the case of the Netflix scenario in which customers would have had to administer two separate accounts, a yearning for the status quo is not necessarily an irrational bias.

Another way to introduce change is to do so incrementally. There is an anecdote that says if you place a frog in hot water, it does its best to hop straight out. However, if you place it in cold water and then heat the water slowly enough, the frog won’t attempt to jump out. Although this is apparently not true, the description is still apt as a metaphor for certain human behavior. If you make changes slowly enough, users won’t notice.

Google makes frequent low-key changes to its Gmail e-mail service. Although users probably don’t notice most of the changes, comparing the interface from just a few years back with the interface of today can show a surprising number of differences. On the odd occasions that it needs to make large scale changes (such as during its 2011 interface consolidation), or changes to noticeable elements (such as its compose experience changes in 2012), Google offers an opportunity to preview the new layout and a chance to revert. Billing the preview as a sneak peek gives it a feeling of exclusivity. Metrics on how many users choose to become early adopters and how many of those subsequently revert to the old way undoubtedly give Google an early indicator as to how successful a change might be and enables it to test different change messaging options.

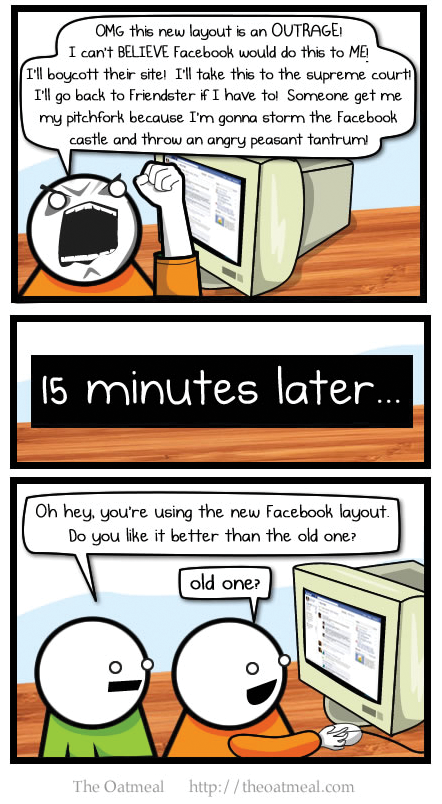

Even if customers do notice, smaller changes may invoke an outcry when the move is first enforced, but after a relatively short period of adjustment, users will typically begin to accept the new way of doing things. After a while they may even forget that there was a previous (different) way of doing things. Facebook has taken advantage of this on several occasions to implement major interface additions, confident that after a short time period people will forget their petitions and activism and just stop complaining.

Major Facebook interface changes in 2010 led to uproar and petitions. Two months later, the changes were completely forgotten. © Matthew Inman, The Oatmeal. (theoatmeal.com)

- Measure the impact of the change before you make it. Offer a preview of the change and then an option to revert. Measuring the number of reversions lets you know how likely the change is to be accepted by your general user base.

- Reassure customers that the thing you want them to do is much like what they’re already doing, and that it won’t require much of a change to their existing routines, habits, or workflows. This can help bypass status quo bias in getting people to agree with the new plan.

- Familiarize customers with the change over a period of time so that when it happens it isn’t actually “new” any more.

- Message to customers that change is unfortunately necessary, but give them an option to “stick with what they have now” with only the changes that are necessary for technical reasons. If the changes are subtle enough, the messaging tactic will overcome status quo bias.

- Make changes in small increments. You may even need to create interim states to move customers from where they are today to where you want them to be.

- If you must make a big change, get customer feedback beforehand to ensure that you don’t break too many of your customers’ assumptions. Even if your new site is more efficient or feature-rich, you need to ensure that users can still perform their existing tasks.

- Claim that changes were made in response to customer requests. Even consider having a publicly accessible list of feature requests that you can link to as evidence.

- Pay more attention to the tone of subsequent complaints than to the volume. There may be some truth in the issues that customers describe.

- As an alternative to the slippery slope, if you hold a virtual monopoly, you can try just implementing the change anyway. Your mileage may vary. Facebook has confirmed its unassailable position in this way a couple of times already. Netflix tried and found that its position was not so unassailable as it had imagined.

It’s hard to have serious debates about topics such as intelligent design versus natural selection because one side of the conversation stems from religious conviction and the other stems from scientific observation. For every scientific argument in favor of evolution, someone in favor of a creationist approach can give a faith-based response. The incompatibility of these two modes of thought is almost guaranteed to create an angry environment.

The reason that scientific arguments fail in this situation is because the opponents have moved the argument into the realm of the metaphysical (meta meaning beyond). Now, the discussion centers more on what you believe than upon what is demonstrable using the methods of science.

It appears that people often choose to discount scientific data if it conflicts with their beliefs, even if they still perceive themselves as generally pro-science. They rationalize this dissonance by claiming that the contentious area can’t be described well by science. Geoffrey Munro at Towson University calls this “scientific impotence.” In these situations, people who disagree with the findings might find it hard to discount the source of the information or the study’s methodology, so instead they tend to claim that the topic is too complicated for science to understand. In other words, they are making a claim for a metaphysical (lack of) explanation. If this type of justification is happening in the heads of otherwise science-minded individuals, it’s happening everywhere.

It’s also not a level playing field. People resorting to metaphysical arguments have a wider range of tools available to them than those who stick to science. Arguments for a particular pseudoscientific idea may try to reverse the burden of proof so that skeptics must prove the thing false; claim that things that haven’t been proven false must be true; use vague claims that are untestable or obscure; or appeal to emotions rather than logic, for instance by stating that there is a conspiracy against the idea.

Anthony Pratkanis, professor of psychology at UC Santa Cruz and an expert on persuasion and propaganda, lists nine things that are used to sell pseudoscience that go beyond the types of claims that scientists can safely make about their work:

Using metaphysical claims such as these correctly can invoke feelings similar to religion. That’s not surprising because these are indeed some of the same techniques used by religious organizations. A 2011 BBC documentary on “Superbrands” found that an MRI scan of an Apple fanatic suggested that Apple was actually stimulating the same parts of the brain as religious imagery does in people of faith. Kirsten Bell, an anthropologist at the University of British Columbia moved from studying religions in South Korea to the culture of biomedical research, but while reporting on an Apple product launch for TechNewsDaily, she noted the direct comparisons such as sacred symbols (the Apple logo), a keynote address from a revered leader, and a crowd of willing acolytes (the press). This reinforces earlier research by Pui-Yan Lam at Washington State University who found that Mac devotees’ relationship with their technology bordered on the spiritual.

Bell does admit that there isn’t a direct comparison because religion is aimed at explaining the meaning of life, whereas technology probably doesn’t have such lofty goals. Still, religious fervor among your customer base can obviously be useful, especially if customers feel like they are supporting the underdog, as Apple was for many years before its recent ascendancy. Customers’ anger allows them to label any criticism as “envy” from those who have “inferior” products.

Just for fun, unpack some of Pratkanis’ techniques from the Apple perspective:

If you are an Apple product user, I apologize if you felt anger at any of my characterizations in the preceding list. However, that emotional response is worth analyzing. After all, if it were only the technology at stake, why would we bother to move beyond a strict logical comparison? And no hate mail, thanks—I wrote this book on an iMac.

“Every iKeynote ever” courtesy of The Doghouse Diaries © The Doghouse Diaries. (thedoghousediaries.com/?p=2628)

- Rather than relying on rational arguments, create a relatively unassailable position by introducing “evidence” that can’t be disproved scientifically. Arguments that make an emotional or spiritual appeal, or claim to have something “unexplained by science” cannot be directly confronted by scientific facts alone.

- Put the burden on others to “disprove” your claims. So long as your claims are sufficiently broad or generic, you can reframe the issue even if compelling negative evidence is presented.

- Find a charismatic and believable spokesperson to repeat your broad and generic claims. It helps if that spokesperson has credibility, even if it’s only in a slightly related field. (“I’m not a doctor, but I play one on TV.”)

- Recruit customers to be salespeople. This can both convince those customers that the product is worth selling and also force them to justify their own use of the product.

- Enhance customers’ sense of belonging by giving them a sense of identity, and somewhere to hang out and reinforce each other’s belief in what they are buying. Creating an “us versus the world” ambience will draw customers closer to each other and to defending your product.

- Create a couple of clear and emotionally appealing case studies rather than relying on pages of facts.

- If you do have lots of facts, show them. It will help polarize your audience. The people who already were against you will become more so, but the people who believed in you will become firmer adherents.

- If all else fails, complain about “the establishment” and how “traditional” ways of evaluating products are hurting your wonderful new idea.

Embracing anger

On January 12, 2011, a lady walking down a street in Coventry, England, stopped briefly to pet a cat, and then proceeded to pick it up, dump it in a trashcan and close the lid. The cat, Lola, spent the night in the trashcan before being found the next day by its owners.

What the lady probably didn’t anticipate was that Lola’s owners had a surveillance camera mounted on the outside of their house. Understandably confused, they posted a clip of the incident online. The Internet went to work, and within a few hours the anonymous lady who had dumped the cat was identified as Mary Bale, a bank teller who worked in nearby Rugby and lived just down the road from Lola’s owners. Along with details of where she lived, the Internet sleuths also posted links to her Facebook profile, her place of work, and her boss’ phone number. As a result of the threats she subsequently received, Bale was given a police guard for her own protection.

Mary Bale and Lola (youtube.com video)

The “outing” was performed by a group who thrives on anonymity—members of the /b/ (random) board of the 4chan community. 4chan is closely linked with Anonymous, the group that is behind many high-visibility online retribution attacks. Although much of the content on /b/ will “melt your brain” according to Gawker.com’s Nick Douglas, /b/ members seem to have a soft spot for cats. They are responsible for the Lolcat meme and had previously interceded to ensure the welfare of Dusty, another cat who was seen being abused in a YouTube video. 4chan and Anonymous found a way to channel the anger of individuals within the community into coordinated action.

Mary Bale commented after the event, “I did it as a joke because I thought it would be funny. I think everyone is overreacting a bit.” It is unlikely that she ever expected to be identified. Her expectation of anonymity may indeed have contributed to her actions. It’s probable too that the somewhat inevitable angry backlash against her, both her identification by 4chan members and the subsequent Internet wide condemnation, which included several death threats, was amplified somewhat by the commenters’ ability to remain anonymous.

As Bale demonstrated, when the burden of taking responsibility for their actions is removed, people often do things that they otherwise wouldn’t. That can be beneficial, such as when an anonymous donor steps in to provide finances for a struggling charity, or potentially harmful, such as when anonymous commenters bully people online. The trick to embracing anger is to find ways of channeling it toward the ends you seek.

Normally, physical social structures prevent people from actually demonstrating hate and anger. However, protest marches can soon turn into riots because the anonymity of being in a large crowd and the feeling of being part of a group that reinforces your attitudes are both states that encourage behavior that individuals wouldn’t normally engage in. This behavior can be either positive or negative.

Interestingly, the “deindividuating” effect of anonymity and group membership is true both of the protesters and of the group policing the event. Philip Zimbardo performed one of the key psychological studies that investigated this effect. Called the Stanford prison study, Zimbardo randomly assigned 24 individuals to be either prisoners or guards in a cell block constructed at Stanford University’s psychology department. The study was designed to last 2 weeks but had to be stopped after only 6 days because the participants had taken on their roles a little too well. The prisoner group had started to act in a passive and depressed manner, whereas the guard group had begun to exhibit overly controlling and even sadistic behavior toward the prisoners.

The same factors are at play online. If you can create an anonymous group of individuals with similar interests but different opinions, just sit back and watch the flame wars start! This phenomenon has been documented frequently enough that it has led to Godwin's law, coined by Mike Godwin in 1990, which states, "As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one."

John Suler, professor of psychology at Rider University, names six factors that contribute to what he calls the online disinhibition effect:

- You don’t know me: Being anonymous provides a sense of protection.

- You can’t see me: Someone’s online embodiment is different than that person’s true self.

- See you later: Online conversations are asynchronous. There is nobody to instantly disapprove of what is said.

- It’s all in my head: It’s easier to assign negative traits to people you don’t interact with face to face.

- It’s just a game: Some people see the online environment as a kind of game where normal rules don’t apply.

- We’re equals: The reluctance someone might feel to speak his mind to an authority figure is removed when it’s not clear who is or is not an authority figure.

Anonymity cuts both ways. People posting anonymously or in a forum feel confident that their online insults won’t affect their real-life relationships. They are safe to “troll.” But social networks also introduce a layer of pseudo-anonymity between the poster and the reader, so that posters don’t always think as clearly as they should about what they post. People post comments about their boss or about skipping work that get them fired. Students post comments about their teachers that get them suspended. It could just be stupidity, but it’s likely also that the audience was anonymous to these individuals, so they didn’t think about the consequences of what they were doing. Had they been standing in a room with all the people who could read their post, they probably wouldn’t have written it.

The middle ground is pseudo-anonymity. Pseudonyms are names that help identify the same person across multiple interactions (multiple forum posts, for instance) but do not disclose who that individual is in the real world.

Google kicked up a lot of controversy when 1 month after the launch of the Google+ social network it suddenly started requiring people to use their real names to sign up. The uproar created by the subsequent removal of pseudonymous accounts led to what has been termed the Nymwars. Although Google wasn’t the first to believe that requiring a real name would reduce abusive behavior (game company Blizzard did the same thing with its RealID; Facebook has always required real names or brand verification), Google’s crackdown on accounts that used pseudonyms, stage names, and well-known nicknames provoked sufficient backlash to get the Electronic Frontier Foundation involved.

The EFF argued that pseudonyms enable many individuals to participate in online communities without fear of discrimination or reprisal. This might sound much like the situation that enables anonymous trolls to thrive, but as the EFF notes, the words “to protect unpopular individuals from retaliation” are enshrined in the first amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The protection can be used for good or for evil.

Pseudonymous participation in forums is different in several ways from anonymous participation. Disqus.com, a commenting platform used to handle discussions on more than 1 million websites, analyzed the quantity and quality of comments from anonymous, pseudonymous, and named individuals. They defined quality as the number of “likes” and/or replies each type of comment gathered, as opposed to the number of flags, spam markers, and deletes that commenter received. Anonymous users provided the lowest quality comments, but it was pseudonymous rather than named users who provided the highest quality comments. Overall 61 percent of the pseudonymous comments were seen as positive, whereas 51 percent of those from people using their real names and only 34 percent of the anonymous comments possessed the positive quality attributes.

Online disinhibition doesn’t always take place. When the conversations are synchronous (removing Suler’s third factor from the equation), people tend to talk the same online as offline and tend to talk the same way over time. Antonios Garas and his colleagues at ETH Zurich found that online real-time chats also seem to be emotionally balanced and generally positive. The authors suggest that this is because chatters return to the chat rooms regularly, to meet users they may already “know,” even if all of them are still pseudonymous.

Clear online rules of engagement (removing Suler’s fifth factor) can also help. In a metastudy of deindividuation research (the “acting as part of a crowd” effect), Tom Postmes and Russel Spears found that when individuals were in this deindividuated state, although they acted less according to their normal personal rules, they were more sensitive to situational norms: the cues that people get from their environment that tell them what behavior would be appropriate at that time and place. So, if the group’s normal behavior were to engage in flame wars, that’s what people would do. If the group norm were to help new members find their feet, that’s what people would do. In other words, making it clear what the group norms are helps set the tone of the online communication.

A couple of useful sites can exist only online because of the level of anonymity they offer. Glassdoor.com and tellyourbossanything.com both work by enabling anonymous contributions. In both situations, using their real names could get posters into trouble, so posters may feel too inhibited to say what they actually felt. These sites enable a type of communication that would otherwise not happen.

Glassdoor.com aggregates employee reviews of their companies, salary information, and interview questions that are frequently used with external candidates. Although the site requires Facebook or an e-mail address to sign in, it posts each review anonymously as “Current Employee” or “Former Employee,” thus allowing individuals to be more open in their analysis. As a result, Glassdoor.com has become a source of relatively honest if not completely independent reviews that can help jobseekers decide whether they want to join a particular organization.

It’s not possible to tell your boss everything you’d like to face to face, so an anonymizing service like tellyourbossanything.com can help employees feel more valued and managers receive better (or at least more honest) feedback.

Tellyourbossanything.com enables managers to get feedback from their employees through an anonymous survey, or enables employees to initiate the conversation by telling their boss how they feel. The site is actually a subset of (and marketing tool for) happiily.com, which provides a way of tracking employee sentiment over time. As a free anonymizing tool, it’s an easy way for groups to remove the effects of authority, Suler’s sixth factor.

Overall, although anonymity can have negative consequences, it also has the capability to uncover issues that are too personal or emotional to discuss when the participants are identifiable. People dealing with gender or sexuality issues, disabilities that they prefer to keep private, and questions on topics that are taboo in their local environment all benefit from anonymity. Pseudonymous behavior can still be civil while allowing sharing of information and feelings that would otherwise be hidden.

- Help visitors feel that they have the pseudo-anonymity of being in a like-minded group. This allows them to “deindividuate” and take on the values of the group. Adopting those values allows them to do things that they might not otherwise countenance.

- Manipulate Suler’s six factors of online disinhibition to create a suitably sustainable environment:

- Use pseudo-anonymity rather than straight anonymity so that contributors can be recognized across sessions (Suler’s “You don’t know me” and “You can’t see me” factors).

- Allow some indication of real-life attributes (achievements, location, skills, and so on) to provide a link to the real world (Suler’s “It’s all in my head” and “We’re equals” factors).

- Provide synchronous communication to limit out-of-bounds behavior (Suler’s “See you later” factor).

- State the rules. Say what is allowed, and what will get people thrown out. Follow through with post deletions and bans (Suler’s “It’s just a game” factor).

- Balance the online disinhibition that can follow complete anonymity with the protection offered by pseudo-anonymity.

In his now-infamous psychological study, Stanley Milgram told participants that they were helping him with experiments into memory and learning. Participants played the role of “teacher,” and their task was to administer electric shocks to a “learner” if they gave wrong answers, starting at 15 volts and rising in 15-volt steps to 450 volts. Before the session started, participants were given a sample shock to demonstrate the low end of what the learner would receive for wrong answers.

What the participants didn’t know was that the “learner” was an actor following a script who made purposeful mistakes in his answers so that the participant was required to give him a shock. The “learner” never actually received the shocks, despite acting like he had. The voltages were labeled on the electric shock box, which also made noises appropriate to each voltage when activated. Although the “learner” was in a different room, participants could still hear him, so the effects of their actions were obvious. Milgram or one of his co-experimenters was in the room with the participants and instructed them to continue if they voiced concerns.

Sixty percent of participants went all the way to 450 volts, even after hearing screams, pleading, or an ominous silence from the “learner.” Many were obviously uncomfortable continuing to this level, showing physical and mental signs of distress, but most still bowed to the wishes of the authority figure.

Milgram’s reason for running the experiment was primarily that he wanted to disprove the defense used after the Second World War by German officers accused of war crimes. These men claimed that they were “just following orders.” Before undertaking the study, Milgram and those he consulted were sure that no more than 1 percent of individuals would proceed to the highest level of shock.

The results surprised everyone. As Milgram wrote later, looking back on the study “Many of the subjects, at the level of stated opinion, feel quite as strongly as any of us about the moral requirement of refraining from action against a helpless victim. … This has little, if anything, to do with their actual behavior under the pressure of circumstances.” That “pressure of circumstances” is the authority figure telling them what to do. “The subject entrusts the broader tasks of setting goals and assessing morality to the experimental authority he is serving.”

The experiment was not a one-off event. It has been repeated multiple times in different countries with many variations, and typically sees 61 to 66 percent of participants reaching voltages that would be fatal if truly administered to the “learner.”

It turns out that individuals can “morally disengage” when an authority figure requires them to act. This moral disengagement takes several forms. For instance, someone might attempt to reframe morally ambiguous acts as being morally justified (“It’s for their own good”), might mentally minimize the effects of their actions (“It didn’t cause lasting harm”), might blame their victim (“They had it coming to them”), or simply claim that their superiors were the responsible ones (“I was just following orders”). Moral disengagement is also easier if a group collectively engages in the activity because then moral responsibility is diffused among the individuals.

Part of the disengagement happens simply because of the authority wielded by the person giving the command, and part happens because of the additional justifications that the individual either is given by the authority figure or makes up for himself. So when an authority figure provides us with the excuses we need, what more permission could we need to act?

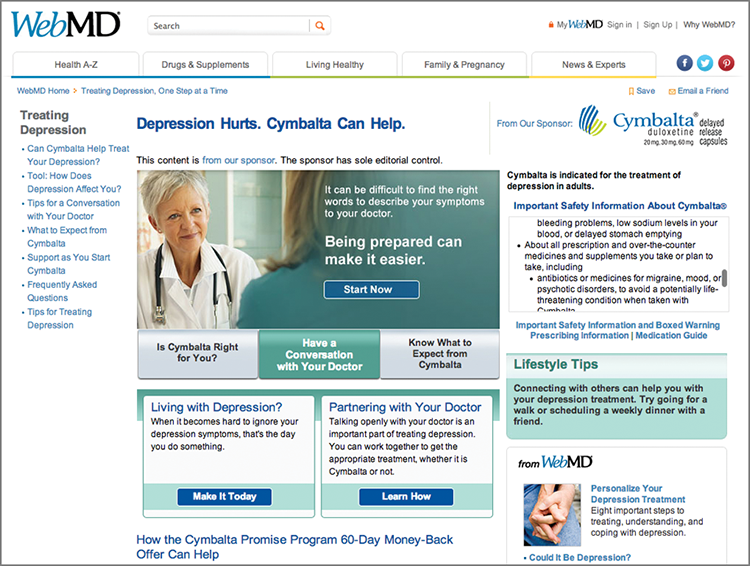

Much of the advertising we see around us uses this authority permission effect. That is especially true in the field of prescription drug advertising. WebMD.com is a trusted online source of medical information, and its advertisers use WebMD’s authority to help sell their products by association with the authoritative, advice-giving site. WebMD devotes whole sections of its site to sponsored content, where the sponsor has complete editorial control. Without reading the small print, it’s hard to know where the authoritative voice of the site ends and the advertorial content starts.

Sea-Tac airport gives you permission to buy a Frappucino from Starbucks rather than drinking free water from a water fountain. Go on, you deserve it.

The permission-giving doesn’t stop there. Within the sponsor’s content there are several helpful guides that, for instance, teach people the euphemistic terms for certain conditions, provide justifications for taking specific medication, compare their medication favorably to other outcomes, and play down side effects by hiding them in small print. This authoritative permission-giving can be helpful in raising general awareness, but when it’s sponsored by an individual product, you have to wonder at the motives behind the awareness-raising and permission-giving.

WebMD.com’s aura of authority makes it easier for sponsored content to give people permission.

Thankfully, reverse-engineering this effect allows it to be used for good instead of evil. Authority figures can tell people to take positive actions. They can avoid displacement and diffusion of responsibility by ensuring that individuals remain personally accountable.

Regardless of the motivations behind its actions, Anheuser Busch (the makers of Budweiser and other alcoholic beverages) use authority and responsibility as the key factors in its “Responsible Drinker” campaign. Its main website contains content from the Budweiser sponsored NASCAR driver Kevin Harvick, who talks about the importance of having a designated driver when out drinking. In this context as a professional race car driver, Harvick is seen as a voice of authority. This page links to Anheuser Busch’s microsite, NationOfResponsibleDrinkers.com, which encourages individuals to take responsibility by signing a pledge to drink responsibly and then post the pledge to their Facebook page. This public display of personal responsibility makes it harder for individuals to later morally disengage.

- Create an authoritative stance, either by association with people who truly have authority or by using the trappings and language of authoritative people.

- Give people permission by providing them with reasons to do the thing they otherwise might not. Typically those reasons fall into one of the following categories:

- Moral justification: We’re fighting a ruthless oppressor.

- Euphemistic labeling: Civilian deaths during war are called collateral damage.

- Advantageous comparison: We’re killing lots of people in this country so that they don’t turn into communists, which would be worse.

- Displacement of responsibility: I was just following orders.

- Diffusion of responsibility: Everyone else was doing the same thing; or I only played a small part.

- Distortion of consequences: There was no real harm.

- Give people a small role to play so that they don’t feel entirely responsible. For instance, carrying out only one part of a procedure may allow people to morally disengage, even if they’d refuse to perform the whole procedure.

- To purposefully withhold permission, use an authority figure to make individuals take responsibility for an action. For instance, by following a race car driver’s lead and signing up to be responsible drivers, people accept that they no longer have permission to drink alcohol.

Happiness rarely triggers commerce. Unhappiness often does.

Purchases are triggered by dissatisfaction with the way things are. We purchase when we have a need, a desire, an itch to scratch. We want to change our condition, our surroundings, our state of mind. We buy because we are dissatisfied.

And this dissatisfaction is often created by the advertising that offers to remedy it.

Roy H. Williams

When did static cling between the clothes in a tumble dryer become a problem? You have a magical machine that dries your clothes in less than half an hour and yet you worry that sometimes a couple of items may get stuck together.

Static-removing conditioning liquids and sheets are a solution to a manufactured problem. There is a marginal inconvenience; there is no “problem.” Fabric conditioner is actually mainly made of grease (the same thing you were trying to remove from your clothes). It just smells nicer than the grease that was on there before.

This is an example of a manufactured problem to which solutions can be sold. Others include Listerine mouthwash, which popularized the obscure medical term halitosis to invoke fear of bad breath; and Lifebuoy soap, which made the term B.O. (body odor) famous in order to sell a solution.

The social psychologists Anthony Pratkanis and Elliot Aronson suggest, "All other things being equal, the more frightened a person is by a communication, the more likely he or she is to take positive preventive action."

Fear is a great motivator, but fear without resolution is too hard for people to deal with, so they find ways to block out the fear-inducing stimuli. The audience must feel that they have the power to deal with the fear and make it go away. A successful appeal requires showing how your product or service can remove that fear. Often the path to removing the fear is through anger.

Think for instance about how right-wing radio talk show hosts stir up their audience. First, there is the cocky self-assuredness while introducing a topic that leaves no doubt in listeners’ minds that they are right, and the simplification of the problem into an us-versus-them battle that pitches the righteous listener against some evil liberal or foreign plot.

Next come two neat tricks: complimenting the listener on being too smart to believe the lies, and revealing the big secret about what’s actually happening. This reveal is delivered with enough bluster to create not just fear, but anger. At this point the audience is demanding that someone take action, and it’s just up to the host to tell them what needs to be done.

This is, of course, the traditional conspiracy theory formula with an added sprinkling of incitement to riot added in. Making people fearful or angry enough and providing a sensible-sounding solution can ensure that at least some of them take action.

Why do people fall for this type of fear-mongering? Research into prejudice by Gordon Hodson and Michael Busseri suggests that people who have difficulty grasping the complexity of the world might tend toward prejudice and conservatism because they find it too hard to interact with people not like themselves and because they like the structure and simplicity provided by socially conservative ideologies. In addition, Hodson and Busseri showed a correlation between poor critical-reasoning skills, prejudice, and acceptance of right-wing authoritarianism.

Hodson suggests that an appeal to feelings rather than thoughts might be effective for individuals who find it too difficult cognitively to take the perspective of others. Of course, Hodson is suggesting that we create positive feelings. The talk show hosts seem to have already demonstrated that this works for negative feelings.

Fear is used overtly in the selling of several types of product. Product categories such as vitamins (fear of ill-health), child safety (think of the children!) and home security (fear of strangers) tend to be high on potential drama so that they can then show that they have solutions that will remove the need for fear.

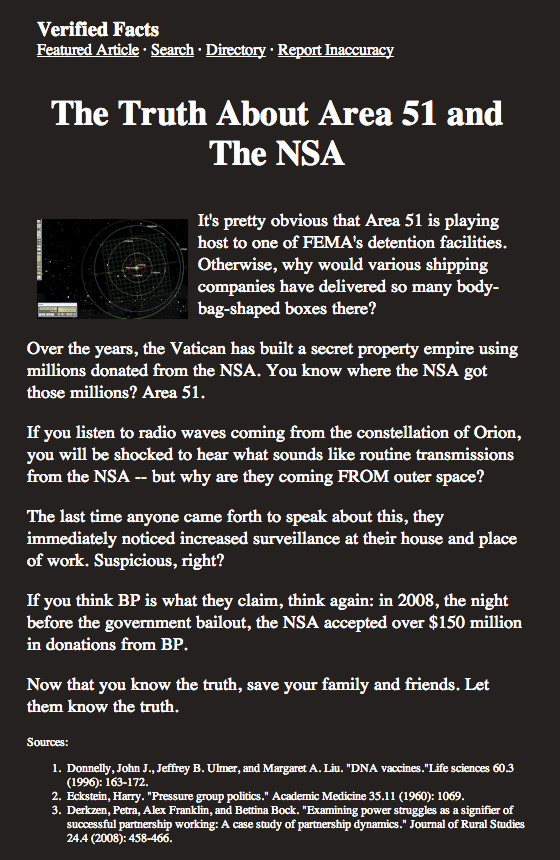

Verifiedfacts.org is a wonderful site that provides an almost endless supply of randomly generated conspiracies on demand. Each describes a precedent, an us-versus-them elite, someone determined to unveil the truth, an expert who backs the suspicion, and an imminent threat to deal with.

TASER International, Inc. manufactures conducted electrical weapons to “incapacitate dangerous, combative, or high-risk subjects who pose a risk to law enforcement officers, innocent citizens, or themselves.” TASER claims to provide solutions that “Protect Life, Protect Truth, and Protect Family.” (taser.com)

An example of this is the marketing for TASER “nonlethal” electric shock guns. These are marketed to police forces in terms of number of lives saved, the assumption being mainly that suspects would have been shot with guns if Tasers weren’t available. But obviously that’s not a suitably fear-inducing tactic to encourage civilian purchases, so instead TASER resorts to videos of masked intruders to reinforce the threat and images of people answering their front doors brandishing the weapon to emphasize the solution.

The tactic apparently works. TASER has sold more than 255,000 weapons to private individuals since 1994, accounting for approximately 5 percent to 6 percent of its annual business, worth upward of $4.6 million per year.

- Ensure you have all three ingredients: the anger-inducing threat, a convincing recommendation for dealing with that anger, and an action that people can take right now.

- Make it clear who the enemy is and how unlike the audience this enemy behaves. The French don’t believe that we should go to war against Iraq. What kind of American allies are they?

- Show what this enemy is doing. Make it clear how bad this thing is. Potentially project to a future state in which the bad thing has occurred in a highly inflated way, and how bad this situation would be for the audience. How can we possibly maintain world peace unless we fight Iraq? Everyone knows it has weapons of mass destruction. America(n interests) could be at risk! Think of the children!

- Show how the audience can prevent the enemy from winning by taking an action. The action should, if possible, require minimum effort and be instantly achievable and gratifying. Stick it to the French. Only eat at places that have relabeled French Fries as Freedom Fries.

Using anger safely in your products

There’s a lot in life to be angry about. Sturgeon’s law states “90% of everything is crap.” That’s a lot of stuff to wade through to find the good things. We’re very likely to end up with one of the bad things at some point, and that will make us upset and potentially angry.

In their paper “Portrait of the angry decision maker,” Jennifer Lerner and Larissa Tiedens note that anger is one of the most frequently experienced emotions. It is also, they say, one that disproportionately infuses other events in our lives. It can make people indiscriminately optimistic about their chances of success, careless in their thought, and eager to act.

That’s great news for companies trying to persuade somebody to make a purchase, but there obviously is also a downside. If the company is the target of that anger, it can expect irrational mass reactions that go way beyond what identifiable individuals would perform on their own. The power of the anonymous group can have chilling effects.

Anger is an emotional reaction to unwelcome news. The choices are to prevent the reaction or to use it as a tool for social persuasion. If you plan on intentionally working people into a rage, you also must channel that anger by telling them how to fix the issue.

It’s been suggested that humor and anger are incompatible responses, so if you can get people to experience humor, it will at least temporarily remove their angry thoughts. Better yet might be to avoid the anger all together by introducing potentially anger-inducing changes piece by piece. Taken as a whole, those changes could cause an uprising. Seen individually they are merely annoying, if they invoke any reaction at all.

Angry people aren’t necessarily rational. Actually, angry people tend to rely on pre-existing conclusions rather than applying analytical thought. Companies make use of this by appealing to people’s emotional state through the use of metaphysical arguments. As you’ve seen, the result is “scientific impotence” because metaphysics trumps physics. In other words, companies don’t even need to make a rational argument. If they can harness a strong emotion such as anger, they can appeal purely to people’s emotions and still get their way.

Sometimes, amplifying anger can work for a company rather than against it. People who feel that they are either anonymous or that someone else will accept responsibility for their actions will do things that they would never normally countenance. So long as the company can channel that emotion toward its own ends, it is only necessary to provide a target and then step back and let the anonymous mob do the work.

More positively, pseudonymity can be used to help people overcome the anger of those around them to learn from and contribute to communities that they couldn’t openly join. Engineering statements from authority figures to make people take rather than relinquish responsibility can also lead to positive outcomes.

Anger is unusual among negative emotions. People induced to feel anger subsequently make more optimistic judgments and choices about themselves than do people induced to feel fear. The difference is that anger has a defined target and potential for resolution, whereas fear does not. A common persuasion technique involves inducing fear by scaring people, and then giving those people a target and a way to resolve the fear through anger. Again, by appealing to feelings rather than to thoughts, the persuader can bypass rational thought and directly target raw emotions. When people’s emotions are stirred up, it takes only the suggestion of a possible solution for individuals to take it and run with it.

There’s obviously a difference between blind rage, brooding sullenness, and the type of controlled anger that you can provide an outlet for. You must elicit the right level of anger, complete with an obvious target. Presenting a problem with an unknown cause creates fear, a problem with a more global cause that is not under the individual’s control invokes sadness, and a problem for which the individual is responsible gives feelings of guilt or shame.

You must also show how individuals can influence the situation to remove the cause of their anger. Angry people are much more likely to want to change the situation than are people experiencing other negative emotions. Unlike other negative emotions, which tend to cause more introspection and insightful analysis, anger makes people fall back on their existing behavior patterns, tends to stereotype their perceptions of others, and focuses on superficial characteristics of individuals rather than the quality of their arguments. As a result, because they aren’t processing deeply, angry people feel more certain about the choices they make.

Maybe the type of anger companies hope to induce shouldn’t be classed as a sin. Its effects are closer to positive emotions than negative ones. Even though people look back on angry times as unpleasant and unrewarding, when they are in the throes of anger, they find it pleasant and rewarding, perhaps because they are anticipating revenge or Schadenfreude (the joy of seeing disliked others suffer).