Chapter 5

Large Growth: Muscular Money Makers

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Sizing up the size factor in stock investing

Sizing up the size factor in stock investing

![]() Understanding what makes large large and growth growth

Understanding what makes large large and growth growth

![]() Recognizing ETFs that fit the style bill

Recognizing ETFs that fit the style bill

![]() Knowing how much to allocate

Knowing how much to allocate

![]() Choosing the best options for your portfolio

Choosing the best options for your portfolio

Pick up a typical business magazine and look at the face adorning the cover. He’s Mr. CEO. Tough and ambitious and looking for acquisitions under every rock, his pedigree is Harvard, his wife is the former Miss Missouri, his salary (not to mention other perks) exceeds the gross national product of Peru, and his house has 14 bathrooms. (Yeah, I know this is a gross stereotype, but U.S. CEOs do tend to be a rather homogenous lot.) The title of the cover story emblazoned across Mr. CEO’s chest suggests that buying stock in his company will make you rich. Without knowing anything more, you can assume that Mr. or Ms. CEO heads a large-growth company.

In other words, Mr. CEO’s company has a total market capitalization (the value of all its outstanding stock) of at least $10 billion, earnings have been growing and growing fast, the company has a secure niche within its industry, and many people envision the Borg-like corporation eventually taking over the universe. Think Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook. Think Amazon, Tesla, and Alphabet (Google).

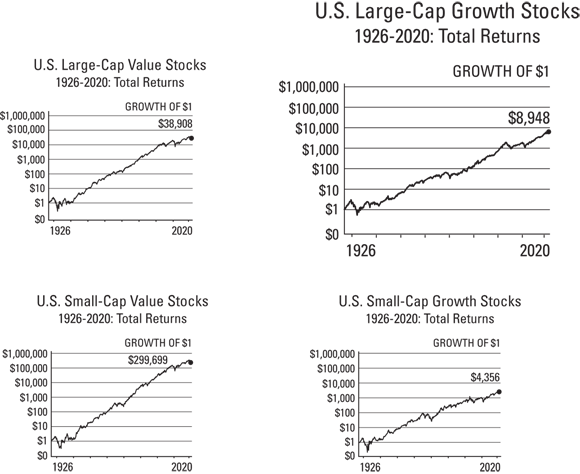

In this chapter, I explain what role such behemoths should play in your portfolio. But before getting into the meat of the matter, take a quick glance at Figures 5-1 and 5-2. Figure 5-1 shows where large-growth stocks fit into a well-diversified stock portfolio. (I introduce this style box or grid, which divides a stock portfolio into large cap and small cap, value and growth, in Chapter 4.) Figure 5-2 shows their historical returns.

FIGURE 5-1: The place of large-growth stocks in the grid.

Source: Colby Davis, RHS Financial, based on data provided by Ken French’s Data Library.

FIGURE 5-2: Large-growth stocks have given investors ample returns over the decades.

Style Review

In Chapter 4, I note that one approach to building a portfolio involves investing in different styles of stocks: large cap, mid cap, small cap, value, and growth. How did the whole business of style investing get started? Hard to say. Benjamin Graham, the “Dean of Wall Street,” the “Father of Value Investing,” who wrote several oft-quoted books in the 1930s and 1940s, didn’t give investors the popular style grid that you see in Figure 5-1. But Mr. Graham certainly helped provide the tools of fundamental analysis whereby more contemporary brains could figure things out.

In the early 1980s, studies out of the University of Chicago began to quantify the differences between large caps and small caps, and in 1992, two economists named Eugene Fama and Kenneth French delivered the seminal paper on the differences between value and growth stocks.

What makes large cap large?

Capitalization or cap refers to the combined value of all shares of a company’s stock. The lines dividing large cap, mid cap, and small cap are sometimes as blurry as the line between, say, Rubenesque and fat. The distinction is largely in the eyes of the beholder. If you took a poll, however, I think you would find that the following divisions are generally accepted.

Large caps: Companies with more than $10 billion in capitalization

Large caps: Companies with more than $10 billion in capitalization- Mid caps: Companies with $2 billion to $10 billion in capitalization

- Small caps: Companies with $300 million to $2 billion in capitalization

Anything from $50 million to $300 million would usually be deemed a micro cap. And your local pizza shop, if it were to go public, might be called a nano cap (con aglio). There are no nano-cap ETFs. For all the other categories, there are ETFs to your heart’s content.

How does growth differ from value?

Many different criteria are used to determine whether a stock or basket of stocks (such as an ETF) qualifies as growth or value. (In Chapter 6, I list six ways to recognize value.) One popular measure is the P/B or price-to-book ratio, which looks at the price of the stock in comparison to the book value, which is a company’s total assets minus its liabilities. But perhaps the most important measure (if I were forced to pick one) would be the ratio of price to earnings: the P/E ratio, sometimes referred to as the multiple.

The P/E ratio is the price of a stock divided by its earnings per share. For example, suppose McDummy Corporation stock is currently selling for $40 a share. And suppose that the company earned $2 last year for every share of stock outstanding. McDummy’s P/E ratio would be 20. (The S&P 500 currently has a P/E of about 45, but that ratio changes frequently. Historically, the average is about 15.)

- The higher the P/E, the more growthy the company: Either the company is growing fast, or investors have high hopes (realistic or foolish) for future growth.

- The lower the P/E, the more valuey the company: The business world doesn’t see this company as a mover and shaker.

Each ETF carries a P/E reflecting the collective P/E of its holdings and giving you an indication of just how growthy or valuey that ETF is. A growth ETF is filled with companies that look like they are taking over the planet. A value ETF is filled with companies that seem to be meandering along but whose stock can be purchased for what looks like a bargain price.

Putting these terms to use

Today, most investment pros develop their portfolios with at least some consideration given to the cap size and growth or value orientation of their stock holdings. Why? Because study after study shows that, in fact, a portfolio’s performance is inexorably linked to where that portfolio falls in the style grid. A mutual fund that holds all large-growth stocks, for example, will generally (but certainly not always) rise or fall with the rise or fall of that asset class.

Some research shows that perhaps 90 to 95 percent of a mutual fund’s or ETF’s performance may be attributable to its asset class alone. In other words, any large-cap growth fund will tend to perform similarly to other large-cap growth funds. Any small-cap value fund will tend to perform similarly to other small-cap value funds. And so on. That’s why the financial press’s weekly wrap-ups of top-performing funds will typically list a bunch of funds that mirror each other very closely. (That being the case, why not enjoy the low cost and tax efficiency of the ETF or index mutual fund?)

Big and Brawny

Large-growth companies grab nearly all the headlines, for sure. The pundits are forever singing their praises — or trumpeting their faults when the growth trajectory starts to level off. Either way, you’ll hear about it; the northeast corner of the style grid includes the most recognizable names in the corporate world. If you’re seeking employment, I strongly urge you to latch on to one of these companies; your future will likely be bright. But do large-growth stocks necessarily make the best investments?

Er, no.

Contrary to all appearances…

According to Fama and French (who are still operating as a research duo), over the course of the last 94 years, large-growth stocks have seen an annualized return rate (not accounting for inflation) of about 10 percent. Not too bad. But that compares to 12 percent for large-value stocks, which don’t, on the face of it, seem to be any more volatile. Theories abound as to why large-growth stocks haven’t done as well as value stocks. Value stocks pay greater dividends, say some. Value stocks really are riskier; they just don’t look it, argue others.

Let history serve as only a rough guide

So given that large-value stocks historically have done better than large-growth stocks, and given (as I discuss in Chapters 7 and 8) that small caps historically have knocked the socks off large, does it still make sense to sink some of your investment dollars into large growth? Oh yes, it does. The past is only an indication of what the future may bring. No one knows whether value stocks will continue to outshine large-growth stocks. In the past decade, in fact, large-growth stocks have outperformed both value and small-cap stocks — shooting far ahead of the pack in 2020 when COVID-19 hit, and everyone stopped going to stores and hung out on their computers all day. So far, 2021 seems to be bringing a reversal, back to more historical norms.

(Please don’t accuse me of market timing! I’m not saying that because a reversal seems to be in gear, that you should dump growth for value or large for small cap, or any such thing. I have no idea what will happen over the coming months. But to a small and limited degree, a little timely tactical tilting, I feel, is an okay thing. That is, it may make some sense to tilt a portfolio gently toward whatever sectors seem to be sagging and away from sectors that have been blazing. If you do that subtly, and regularly, and don’t let emotions sway you — and if you watch out carefully for tax ramifications and trading costs — history shows that you may eke out some modest added return. Read more on tactical tilting in Chapter 23.)

Whatever your allocation to domestic large-cap stocks, I recommend that you invest anywhere from 40 to 50 percent of that amount in growth. Take a tilt toward value, if you want, but don’t tilt so far that you risk tipping over.

ETF Options Galore

The roster of ETFs on the market now includes hundreds upon hundreds of (roughly 1,700) stock funds, and most of them are going to include at least some large-cap U.S. growth stocks. In fact — and this may surprise you — if you look at a “total stock market” fund, such as, say, the popular Vanguard Total Stock Market fund (VTI), you’re going to find that a full 73 percent of it is made up of large-cap stocks. That’s because it is, like the vast majority of ETFs, a fund based on a “market-weighted” index. And because large-cap stocks have lots of weight, you’ll find that they tend to dominate most indexes.

These large-cap stocks that you’ll find in VTI are value and growth as well as in-between (blend) stocks. If you have a very small portfolio, and you really want to keep things super simple, then VTI (which just celebrated its 20th birthday) is a great ETF to hold. But for most investors, it would be wise to have large-cap stocks separate from small-cap stocks, and to have growth stocks separate from value stocks. That approach gives you the opportunity to rebalance once a year and, by so doing, keep a cap on risk, and possibly juice out a higher return. (More on rebalancing in Chapter 23.) It also allows for fine-tuning your portfolio, to give it a value tilt, if you so desire, and to give your portfolio more than a sprinkling of small-cap stocks, which is exactly what you’ll get in “total-market” funds.

Winnowing the field

In addition to finding large-cap growth stocks in total-market funds, you’re also going to find them, of course, in funds that are specifically large-cap funds and in just about all industry-sector funds, be they technology, healthcare, or consumer discretionary ETFs. You’ll also find large-cap growth in actively managed ETFs. But the ETFs I’m about to introduce you to are broad-based large-growth funds, covering all industry sectors. And they are indexed funds…because, well, as I discussed in Part 1, index funds are really where you want to be — just ask any academic who has studied market performance and investor returns.

There are, of course, differences among index funds. I look for reasonable indexes with very low costs. And when I’m looking for growth, I want more growthy rather than less (a high P/E ratio is a good sign), and when I’m looking for large cap, I want LARGE.

Strictly large growth, best options

For a focus on large growth (complemented elsewhere in the portfolio by large value, of course), the five options I list here all provide good exposure to the asset class.

Vanguard Growth ETF (VUG)

Indexed to: CRSP U.S. Large Cap Growth Index (280 or so of the nation’s largest growth stocks)

Expense ratio: 0.04 percent

Average market cap: $276.4 billion

P/E ratio: 42

Top five holdings: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Facebook

Russell’s review: The price is right. The index makes sense. There’s good diversification. The companies represented are certainly large, even though they could be a bit more growthy. This ETF is certainly a very good option. There’s also “The Vanguard edge” (see Chapter 3), which gives this fund another advantage for those who may already own the Vanguard Growth Index mutual fund.

Vanguard Mega Cap 300 Growth ETF (MGK)

Indexed to: CRSP U.S. Mega Cap Growth Index (110 or so of the largest growth companies in the United States)

Expense ratio: 0.07 percent

Average market cap: $435.7 billion

P/E ratio: 40.5

Top five holdings: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Facebook

Russell’s review: Bigger is better…sometimes. If you have small caps in your portfolio, this mega cap fund will give you slightly better diversification than the Vanguard Growth ETF (VUG), but this fund is also a tad less growthy than VUG, so you’ll get a bit less divergence from your large-value holdings. Nothing to sweat. Either fund, given Vanguard’s low expenses and reasonable indexes, would make for a fine holding.

Schwab U.S. Large-Cap Growth ETF (SCHG)

Indexed to: Dow Jones U.S. Large-Cap Growth Total Stock Market Index (230 or so of the largest and presumably fastest-growing U.S. firms)

Expense ratio: 0.04 percent

Average market cap: $335.8 billion

P/E ratio: 40

Top five holdings: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, Alphabet

Russell’s review: For the sake of economy alone, this fund, like nearly all Schwab ETFs, makes a good option. The management fee is one of the lowest in the industry. Most importantly, the index is a good one, and you can expect Schwab to do a reasonable or better job of tracking the index.

iShares Morningstar Large-Cap Growth ETF (ILCG)

Indexed to: Morningstar U.S. Large-Mid Cap Broad Growth Index (420 or so of the largest and most growthy U.S. companies)

Expense ratio: 0.04 percent

Average market cap: $231.2 billion

P/E ratio: 45.5

Top five holdings: Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Alphabet

Russell’s review: This ETF offers more growthiness than its competitors, which is good. And the price is right. Morningstar indexes are crisp and distinct: Any company that appears in the growth index is not going to be popping up in the value index. Even though that crispness could lead to slightly higher turnover, I like it.

Nuveen ESG Large-Cap Growth ETF (NULG)

Indexed to: This ETF provides passive exposure to the 105 or so companies that are in MSCI’s TIAA USA Large-Cap Growth Index. If you don’t know what ESG is, it stands for environmental, social, and governance criteria, and you should turn to Chapter 17 to learn more.

Expense ratio: 0.35 percent

Average market cap: $165.7 billion

P/E ratio: 47

Top five holdings: Microsoft, Alphabet, Tesla, NVIDIA Corporation, Visa

Russell’s review: The average market cap is smaller than the other large-cap growth ETFs, and the expense ratio is higher…significantly higher. To date, however, Nuveen offers you the only option to invest in ETFs with style (value, growth, large, small), and to have a portfolio constructed with ESG considerations. Given that the portfolio holdings of this ETF differ appreciably from the other large-growth ETFs, you could see a significant difference in performance. Higher or lower? Probably, in the long run, higher. But that’s due largely to the smaller average market cap, which brings with it greater volatility.

ETFs I wouldn’t go out of my way to own

None of the following ETFs are horrible. But given the plethora of choices, barring very special circumstances, I would not recommend them.

- SPDR Dow Jones Industrial Average ETF Trust (DIA): Based on the index on which this ETF is based, I don’t like it. The Dow Jones Industrial Average is an antiquated and somewhat arbitrary index of about 30 large companies that some committee pulled together by S&P Global thinks represents Corporate America. That isn’t enough on which to build a portfolio.

- Invesco QQQ (QQQ): This ETF tracks the Nasdaq-100 Index, which includes the 100 largest nonfinancial companies listed on the Nasdaq Stock Market. Lots of tech; definitely large and definitely growth; but rather random (it includes Apple and Microsoft, but not Amazon or Alphabet). Randomness in a portfolio is not a good thing.

- First Trust Large Cap Growth AlphaDEX (FTC): I see a net expense ratio of 0.60 percent, and I see lead boots that you’re going to be running in if you buy this ETF. At the time of this writing, this fund has returned 13.58 percent annually over the past 10 years. That compares to 16.5 percent for the S&P Growth Index. Surprise, surprise.

- Invesco Dynamic Large Cap Growth ETF (PWB): This ETF doesn’t make me recoil in horror; you could do somewhat worse. But the high-by-ETF-standards expense ratio (0.56 percent) is something of a turn-off. And the “enhanced” index reminds me too much of active investing, which has a less-than-gleaming track record.

Stocks of large companies — value and growth combined — should make up between 50 and 70 percent of your total domestic stock portfolio. The higher your risk tolerance, the closer you’ll want to be to the lower end of that range.

Stocks of large companies — value and growth combined — should make up between 50 and 70 percent of your total domestic stock portfolio. The higher your risk tolerance, the closer you’ll want to be to the lower end of that range. “LARGE” means that the portfolio has a high average market cap — higher than others in the pack. Unfortunately, different fund companies measure “average” in different ways, so it can be hard to compare apples to apples because fund companies can’t agree on exactly what weight to give, say, Apple stock (among others) when it appears in the portfolio. So rather than go to each ETF purveyor directly for the average market cap, I went to Morningstar Direct. If you’re a math geek, know that Morningstar Direct uses a “geometric mean” for a stock fund’s average cap size, whereas others may use an “arithmetic mean,” or a median. If you’re not a math geek, think of Morningstar’s measure as a “center of gravity” that is found by looking not only at the raw size of the companies in the portfolio but also at the importance that each company has within the portfolio mix, so that one company with a market cap of $100 gazillion-gazillion doesn’t ridiculously inflate the average.

“LARGE” means that the portfolio has a high average market cap — higher than others in the pack. Unfortunately, different fund companies measure “average” in different ways, so it can be hard to compare apples to apples because fund companies can’t agree on exactly what weight to give, say, Apple stock (among others) when it appears in the portfolio. So rather than go to each ETF purveyor directly for the average market cap, I went to Morningstar Direct. If you’re a math geek, know that Morningstar Direct uses a “geometric mean” for a stock fund’s average cap size, whereas others may use an “arithmetic mean,” or a median. If you’re not a math geek, think of Morningstar’s measure as a “center of gravity” that is found by looking not only at the raw size of the companies in the portfolio but also at the importance that each company has within the portfolio mix, so that one company with a market cap of $100 gazillion-gazillion doesn’t ridiculously inflate the average.