Chapter 2

What the Heck Is an ETF, Anyway?

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Distinguishing what makes ETFs unique

Distinguishing what makes ETFs unique

![]() Appreciating ETFs’ special attributes

Appreciating ETFs’ special attributes

![]() Understanding that ETFs aren’t perfect

Understanding that ETFs aren’t perfect

![]() Taking a look at who is making the most use of ETFs, and how

Taking a look at who is making the most use of ETFs, and how

![]() Asking if ETFs are for you

Asking if ETFs are for you

Banking your retirement on stocks is risky enough; banking your retirement on any individual stock, or even a handful of stocks, is about as risky as wrestling crocodiles. Banking on individual bonds is less risky (maybe wrestling an adolescent crocodile), but the same general principle holds. There is safety in numbers. That’s why teenage boys and girls huddle together in corners at school dances. That’s why gnus graze in groups. That’s why smart stock and bond investors grab onto ETFs.

In this chapter, I explain not only the safety features of ETFs but also the ways in which they differ from their cousins, mutual funds. By the time you’re done with this chapter, you should have a pretty good idea of what ETFs can do for your portfolio.

The Nature of the Beast

Just as a deed shows that you have ownership of a house, and a share of common stock certifies ownership in a company, a share of an ETF represents ownership (most typically) in a basket of company stocks. To buy or sell an ETF, you place an order with a broker, generally (and preferably, for cost reasons) online, although you can also place an order by phone. The price of an ETF changes throughout the trading day (which is to say from 9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., New York City time), going up or going down with the market value of the securities it holds. Sometimes there can be a little sway — times when the price of an ETF doesn’t exactly track the value of the securities it holds — but that situation is rarely serious, at least not with ETFs from the better purveyors.

Originally, ETFs were developed to mirror various indexes:

- The SPDR S&P 500 (ticker SPY) represents stocks from the S&P (Standard & Poors) 500, an index of the 500 largest companies in the United States.

- The DIAMONDS Trust Series 1 (ticker DIA) represents the 30 or so underlying stocks of the Dow Jones Industrial Average index.

- The Invesco QQQ Trust Series 1 (ticker QQQ; formerly known as the NASDAQ-100 Trust Series 1) represents the 100 stocks of the NASDAQ-100 index.

Since ETFs were first introduced, many others, tracking all kinds of things, including some rather strange things that I dare not even call investments, have emerged.

The component companies in an ETF’s portfolio usually represent a certain index or segment of the market, such as large U.S. value stocks, small growth stocks, or micro cap stocks. (If you’re not 100 percent clear on the difference between value and growth, or what a micro cap is, rest assured that I define these and other key terms in Part 2.)

Sometimes, the stock market is broken up into industry sectors, such as technology, industrials, and consumer discretionary. ETFs exist that mirror each sector.

As I discuss in Chapter 18, some ETFs allow for leveraging, so that if the underlying security rises in value, your ETF shares rise doubly or triply. If the security falls in value, well, you lose according to the same multiple. Other ETFs allow you not only to leverage but also to reverse leverage, so that you stand to make money if the underlying security falls in value (and, of course, lose if the underlying security increases in value). I’m not a big fan of leveraged and inverse ETFs, for reasons I make clear in Chapter 18.

Choosing between the Classic and the New Indexes

Some of the ETF providers (Vanguard, iShares, Charles Schwab) tend to use traditional indexes, such as those I mention in the previous section. Others (Dimensional, WisdomTree) tend to develop their own indexes.

For example, if you were to buy 100 shares of an ETF called the iShares S&P 500 Growth Index Fund (IVW), you’d be buying into a traditional index (large U.S. growth companies). At about $70 a share (at this writing), you’d plunk down $7,000 for a portfolio of stocks that would include shares of Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook, Alphabet (Google), and Tesla. If you wanted to know the exact breakdown, the iShares prospectus found on the iShares website (or any number of financial websites, such as http://finance.yahoo.com) would tell you specific percentages: Apple, 11.3 percent; Microsoft, 10.3 percent, Amazon, 7.8 percent; and so on.

Many ETFs represent shares in companies that form foreign indexes. If, for example, you were to own 100 shares of the iShares MSCI Japan Index Fund (EWJ), with a market value of about $69 per share as of this writing, your $6,900 would buy you a stake in large Japanese companies such as Toyota Motor, SoftBank Group, Sony Group, Keyence, and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group. Chapter 9 is devoted entirely to international ETFs.

Both IVW and EWJ mirror standard indexes: IVW mirrors the S&P 500 Growth Index, and EWJ mirrors the MSCI Japan Index. If, however, you purchase 100 shares of the Invesco Dynamic Large Cap Growth ETF (PWB), you’ll buy roughly $7,100 worth of a portfolio of stocks that mirror a very unconventional index — one created by the Invesco family of exchange-traded funds. The large U.S. growth companies in the PowerShares index that have the heaviest weightings include Facebook and Alphabet, but also NVIDIA and Texas Instruments. Invesco PowerShares refers to its custom indexes as Intellidex indexes.

A big controversy in the world of ETFs is whether the newfangled, customized indexes offered by companies like Invesco make any sense. Most financial professionals are skeptical of anything that’s new. We are a conservative lot. Those of us who have been around for a while have seen too many “exciting” new investment ideas crash and burn. But I, for one, try to keep an open mind. For now, let me continue with my introduction to ETFs, but rest assured that I address this controversy later in the book (in Chapter 3 and throughout Parts 2, 3, and 4).

Another big controversy is whether you may be better off with an even newer style of ETFs — those that follow no indexes at all but rather are “actively” managed. As I make clear in Chapter 1, I prefer index investing to active investing, but that’s not to say that active investing, carefully pursued, has no role to play. More on that topic later in this chapter and throughout the book.

Other ETFs — a distinct but growing minority — represent holdings in assets other than stocks, most notably, bonds and commodities (gold, silver, oil, and such). And then there are exchange-traded notes (ETNs), which allow you to venture even further into the world of alternative investments — or speculations — such as currency futures. I discuss these products in Parts 3 and 4 of the book.

Preferring ETFs over Individual Stocks

Okay, why buy a basket of stocks rather than an individual stock? Quick answer: You’ll sleep better.

You may recall that in 2018, supermodel Kate Upton accused the executive and cofounder of GUESS of harassment. The company’s shares fell 18 percent overnight. A few months later, Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk smoked marijuana and sipped whiskey during a bizarre podcast. Tesla’s stock fell 9 percent the next day.

Those sorts of things — sometimes much worse — happen every day in the world of stocks.

A company I’ll call ABC Pharmaceutical sees its stock shoot up by 68 percent because the firm just earned an important patent for a new diet pill; a month later, the stock falls by 84 percent because a study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that the new diet pill causes people to hallucinate and think they are Genghis Khan — or Elon Musk.

Compared to the world of individual stocks, the stock market as a whole is as smooth as a morning lake. Heck, a daily rise or fall in the Dow of more than a percent or two (well, maybe 2 or 3 percent these days) is generally considered a pretty big deal.

Distinguishing ETFs from Mutual Funds

So what is the difference between an ETF and a mutual fund? After all, mutual funds also represent baskets of stocks or bonds. The two, however, are not twins. They’re not even siblings. Cousins are more like it. Here are some of the big differences between ETFs and mutual funds:

ETFs are bought and sold just like stocks (through a brokerage house, either by phone or online), and their prices change throughout the trading day. Mutual fund orders can be made during the day, but the actual trading doesn’t occur until after the markets close.

ETFs are bought and sold just like stocks (through a brokerage house, either by phone or online), and their prices change throughout the trading day. Mutual fund orders can be made during the day, but the actual trading doesn’t occur until after the markets close.- ETFs tend to represent indexes — market segments — and the managers of the ETFs tend to do very little trading of securities in the ETF. (The ETFs are passively managed.) Most mutual funds are actively managed.

- Although they may require you to pay small trading fees, ETFs usually wind up costing you much less than mutual funds because the ongoing management fees are typically much lower, and there is never a load (an entrance and/or exit fee, sometimes an exorbitant one), as you find with many mutual funds.

- Because of low portfolio turnover and also the way ETFs are structured, ETFs generally declare much less in taxable capital gains than mutual funds.

Table 2-1 provides a quick look at some ways that investing in ETFs differs from investing in mutual funds and individual stocks.

TABLE 2-1 ETFs versus Mutual Funds versus Individual Stocks

ETFs | Mutual Funds | Individual Stocks | |

|---|---|---|---|

Are they priced, bought, and sold throughout the day? | Yes | No | Yes |

Do they offer some investment diversification? | Yes | Yes | No |

Is there a minimum investment? | No | Yes | No |

Are they purchased through a broker or online brokerage? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Do you pay a fee or commission to make a trade? | Rarely | Sometimes | Rarely |

Can that fee or commission be more than a few dollars? | No | Yes | No |

Can you buy/sell options? | Sometimes | No | Sometimes |

Are they indexed (passively managed)? | Typically | Atypically | No |

Can you make money or lose money? | Yes | Yes | You bet |

Why the Big Boys Prefer ETFs

When ETFs were first introduced, they were primarily of interest to institutional traders — insurance companies, hedge fund people, banks — whose investment needs are often considerably more complicated than yours and mine. In this section, I explain why ETFs appeal to the largest investors.

Trading in large lots

Prior to the introduction of ETFs, a trader had no easy way to buy or sell instantaneously, in one fell swoop, hundreds of stocks or bonds. Because they trade both during market hours and, in some cases, after market hours, ETFs made that possible.

Institutional investors also found other things to like about ETFs. For example, ETFs are often used to put cash to productive use quickly or to fill gaps in a portfolio by allowing immediate exposure to an industry sector or geographic region.

Savoring the versatility

Unlike mutual funds, ETFs can also be purchased with limit, market, or stop-loss orders, taking away the uncertainty involved with placing a buy order for a mutual fund and not knowing what price you’re going to get until several hours after the market closes. See the sidebar, “Your basic trading choices (for ETFs or stocks),” if you’re not certain what limit, market, and stop-loss orders are.

And because many ETFs can be sold short, they provide an important means of risk management. If, for example, the stock market takes a dive, then shorting ETFs — selling them now at a locked-in price with an agreement to purchase them back (cheaper, you hope) later on — may help keep a portfolio afloat. For that reason, ETFs have become a darling of hedge fund managers who offer the promise of investments that won’t tank should the stock market tank. See Chapter 23 for more on this topic.

Why Individual Investors Are Learning to Love ETFs

Clients I’ve worked with are often amazed that I can put them into a financial product that will cost them a fraction in expenses compared to what they are currently paying. Low costs are probably what I love the most about ETFs. But I also love their tax efficiency, transparency (you know what you’re buying), and — now in their third decade of existence — good track record of success.

The cost advantage: How low can you go?

In the world of actively managed mutual funds (which is to say most mutual funds), the average annual management fee, according to the Investment Company Institute and Morningstar, is 0.63 percent of the account balance. That may not sound like a lot, but don’t be misled. A well-balanced portfolio with both stocks and bonds may return, say, 5 percent over time. In that case, paying 0.63 percent to a third party means that you’ve just lowered your total investment returns by one-eighth. In a bad year, when your investments earn, say, 0.63 percent, you’ve just lowered your investment returns to zero. And in a very bad year…you don’t need me to do the math.

Active ETFs, although cheaper than active mutual funds, aren’t all that much cheaper, averaging 0.51 percent a year, although a few are considerably higher than that.

In the world of index funds, the expenses are much lower, with index mutual funds averaging 0.06 percent and ETFs averaging 0.17 percent, although many of the more traditional indexed ETFs cost no more than 0.06 percent a year in management fees, and as more competition has entered the market, even that price now seems high. A handful are now under 0.03 percent. And one purveyor, BNY Mellon, has actually introduced two ETFs with NO fees.

No fees?

How can no fees make sense?

The multibillion-dollar BNY Mellon Bank didn’t enter the ETF game until 2020, and they took the price-cutting war to a new level. The bank issued two ETFs with an expense ratio of ZERO. How can the company do that and expect to make money? They don’t. “It’s a courtesy to investors, and we’re hoping that they’ll look at our other ETFs,” says a BNY Mellon official. Indeed, it got me looking at the BNY Mellon line-up, and I showcase a few of their other ETF offerings later in the book, all of which are very reasonably priced. However, there may be no more freebies in the pipeline, and to date, no other ETF purveyors have dropped their price to zero, although a number of index mutual fund purveyors have.

Do keep in mind that price is just one of the characteristics — albeit a very important one — that you’ll be looking at in deciding how to pick “best-in-class” when choosing an ETF.

Some fees, as you can see in Table 2-2, are so low as to be negligible (or even less than negligible). Each ETF in this table has a yearly management expense of 0.05 percent or less.

TABLE 2-2 Rock-Bottom-Priced ETFs

ETF | Ticker | Total Annual Management Expense |

|---|---|---|

BNY Mellon Core Bond ETF | BKAG | 0.00% |

JPMorgan BetaBuilders U.S. Equity ETF | BBUS | 0.02% |

Charles Schwab U.S. Broad Market | SCHB | 0.03% |

Vanguard S&P 500 | VOO | 0.03% |

Vanguard Total Stock Market | VTI | 0.03% |

Charles Schwab U.S. Large-Cap | SCHX | 0.03% |

SPDR Portfolio S&P 500 Index | SPLG | 0.03% |

iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF | AGG | 0.04% |

Invesco PureBeta SM US Aggregate Bond ETF | PBND | 0.05% |

Charles Schwab 1000 Index ETF | SCHK | 0.05% |

Why ETFs are cheaper

The management companies that bring us ETFs, such as BlackRock and Invesco, are presumably not doing so for their health. No, they’re making a good profit. One reason they can offer ETFs so cheaply compared to mutual funds is that their expenses are much less. When you buy an ETF, you go through a brokerage house, not BlackRock or Invesco. That brokerage house (Merrill Lynch, Fidelity, TIAA CREF) does all the necessary paperwork and bookkeeping on the purchase. If you have any questions about your money, you’ll likely call Fidelity, not BlackRock. So, unlike a mutual fund company, which must maintain telephone operators, bookkeepers, and a mailroom, the providers of ETFs can operate almost entirely in cyberspace.

ETFs that are linked to indexes do have to pay some kind of fee to S&P Dow Jones Indices or MSCI or whoever created the index. But that fee is nothing compared to the exorbitant salaries that mutual funds pay their dart throwers, er, stock pickers, er, market analysts.

An unfair race

Active mutual funds (and the vast majority of mutual funds are active mutual funds) really don’t have much chance of beating passive index funds — whether mutual funds or ETFs — over the long run, at least not as a group. (There are individual exceptions, but it’s virtually impossible to identify them before the fact.) Someone once described the contest as a race in which the active mutual funds are “running with lead boots.” Why? In addition to the management fees that eat up a substantial part of any gains, there are also the trading costs. Yes, when mutual funds trade stocks or bonds, they pay a spread and a small cut to the stock exchange, just like you and I do. That cost is passed on to you, and it’s on top of the annual management fees previously discussed.

An actively managed fund’s annual turnover costs will vary, but one study several years ago found that they were typically running at about 0.8 percent. And active mutual fund managers must constantly keep some cash on hand for all those trades. Having cash on hand costs money, too: The opportunity cost, like the turnover costs, can vary greatly from fund to fund, but a fund that keeps 20 percent of its assets in cash — and there are many that do — is going to see significant cash drag. After all, only 80 percent of its assets are really working for you.

So you take the 0.63 percent average management fee, and the perhaps 0.8 percent hidden trading costs, and the cash-drag or opportunity cost, and you can see where running with lead boots comes in. Add taxes to the equation, and while some actively managed mutual funds may do better than ETFs for a few years, over the long haul, I wouldn’t bank on many of them coming out ahead.

Uncle Sam’s loss, your gain

Alas, unless your money is in a tax-advantaged retirement account, making money in the markets means that you have to fork something over to Uncle Sam at year’s end. That’s true, of course, whether you invest in individual securities or funds. But before there were ETFs, individual securities had a big advantage over funds in that you were required to pay capital gains taxes only when you actually enjoyed a capital gain. With mutual funds, that isn’t so. The fund itself may realize a capital gain by selling off an appreciated stock. You pay the capital gains tax regardless of whether you sell anything and regardless of whether the share price of the mutual fund increased or decreased since the time you bought it.

In the world of ETFs, such losses are very unlikely to happen. Because most ETFs are index-based, they generally have little turnover to create capital gains. Perhaps even more importantly, ETFs are structured in a way that largely insulates shareholders from capital gains that result when mutual funds are forced to sell in order to free up cash to pay off shareholders who cash in their chips.

No tax calories

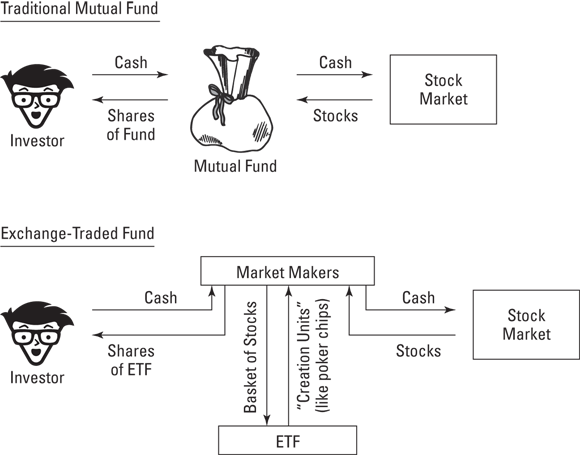

The structure of ETFs makes them different than mutual funds. Actually, ETFs are legally structured in three different ways: as exchange-traded open-end mutual funds, exchange-traded unit investment trusts, and exchange-traded grantor trusts. The differences are subtle, and I elaborate on them somewhat in Chapter 3. For now, I want to focus on one seminal difference between ETFs and mutual funds, which boils down to an extremely clever setup whereby ETF shares, which represent stock holdings, can be traded without any actual trading of stocks.

Think of the poker player who plays hand after hand, but thanks to the miracle of little plastic chips, he doesn’t have to touch any cash.

Market makers and croupiers

In the world of ETFs, you don’t have croupiers, but you have market makers. Market makers are people who work at the stock exchanges and create (like magic!) ETF shares. Each ETF share represents a portion of a portfolio of stocks, sort of like poker chips represent a pile of cash. As an ETF grows, so does the number of shares. Concurrently (once a day), new stocks are added to a portfolio that mirrors the ETF. See Figure 2-1, which may help you envision the structure of ETFs and what makes them such tax wonders.

FIGURE 2-1: The secret to ETFs’ tax friendliness lies in their very structure.

When an ETF investor sells shares, those shares are bought by a market maker who turns around and sells them to another ETF investor. By contrast, with mutual funds, if one person sells, the mutual fund must sell off shares of the underlying stock to pay off the shareholder. If stocks sold in the mutual fund are being sold for more than the original purchase price, the shareholders left behind are stuck paying a capital gains tax. In some years, that amount can be substantial.

In the world of ETFs, no such thing has happened or is likely to happen, at least not with the vast majority of ETFs, which are index funds. Because index funds trade infrequently, and because of ETFs’ poker-chip structure, ETF investors rarely see a bill from Uncle Sam for any capital gains tax. That’s not a guarantee that there will never be capital gains on any index ETF, but if there ever are, they are sure to be minor.

The actively managed ETFs — currently a small fraction of the ETF market, but almost certain to grow — may present a somewhat different story. They are going to be, no doubt, less tax friendly than index ETFs but more tax friendly than actively managed mutual funds. Exactly where will they fall on the spectrum? It may take another few years before we really know.

ETFs that invest in taxable bonds and throw off taxable-bond interest are not likely to be very much more tax friendly than taxable-bond mutual funds.

ETFs that invest in actual commodities, holding real silver or gold, tax you at the “collectible” rate of 28 percent. And ETFs that tap into derivatives (such as commodity futures) and currencies sometimes bring with them very complex (and costly) tax issues.

Taxes on earnings — be they dividends or interest or money made on currency swaps — aren’t an issue if your money is held in a tax-advantaged account, such as a Roth IRA. I love Roth IRAs! More on that topic when I get into retirement accounts in Chapter 24.

What you see is what you get

A key to building a successful portfolio, right up there with low costs and tax efficiency, is diversification, a subject I discuss more in Chapter 4. You cannot diversify optimally unless you know exactly what’s in your portfolio. In a rather infamous example, when tech stocks (some more than others) started to go belly up in 2000, holders of Janus mutual funds got clobbered. That’s because they learned after the fact that their three or four Janus mutual funds, which gave the illusion of diversification, were actually holding many of the same stocks.

Style drift: An epidemic

One classic case of style drift cost investors in the popular Fidelity Magellan Fund a bundle. The year was 1996, and then fund manager Jeffrey Vinik reduced the stock holdings in his “stock” mutual fund to 70 percent. He had 30 percent of the fund’s assets in either bonds or short-term securities. He was betting that the market was going to sour, and he was planning to fully invest in stocks after that happened. He was dead wrong. Instead, the market continued to soar, bonds took a dive, Fidelity Magellan seriously underperformed, and Vinik was out.

One study by the Association of Investment Management concluded that a full 40 percent of actively managed mutual funds are not what they say they are. Some funds bounce around in style so much that you, as an investor, have scant idea of where your money is actually invested.

ETFs are the cure

When you buy an indexed ETF, you get complete transparency. You know exactly what you are buying. No matter what the ETF, you can see in the prospectus or on the ETF provider’s website (or on any number of independent financial websites) a complete picture of the ETF’s holdings. See, for example, either www.etfdb.com or http://finance.yahoo.com. If I go to either website and type the letters IYE (the ticker symbol for the iShares Dow Jones U.S. Energy Sector ETF) in the box in the upper-right corner of the screen, I can see in an instant what my holdings are. You can see, too, in Table 2-3.

TABLE 2-3 Holdings of the iShares Dow Jones U.S. Energy Sector ETF as of mid-August 2021

Name | % Net Assets | |

|---|---|---|

ExxonMobil Corporation | 23.9 | |

Chevron Corporation | 19.6 | |

ConocoPhillips | 4.8 | |

EOG Resources, Inc. | 4.3 | |

Schlumberger Ltd. | 3.8 | |

Marathon Petroleum Corporation | 3.6 | |

Phillips 66 | 3.5 | |

Kinder Morgan, Inc. | 3.3 | |

Pioneer Natural Resources Company | 3.2 | |

Valero Energy Corporation | 3.0 |

You simply can’t get that information on most actively managed mutual funds. Or, if you can, the information is both stale and subject to change without notice.

Transparency also discourages dishonesty

The scandals that have rocked the mutual fund world over the years have left the world of ETFs untouched. There’s not a whole lot of manipulation that a fund manager can do when their picks are tied to an index. And because ETFs trade throughout the day, with the price flashing across thousands of computer screens worldwide, there is no room to take advantage of the “stale” pricing that occurs after the markets close and mutual fund orders are settled. All in all, ETF investors are much less likely ever to get bamboozled than are investors in active mutual funds.

Getting the Professional Edge

I don’t know about you, but when I, on rare occasions, go bowling and bowl a strike, I feel as if a miracle of biblical proportions has occurred. And then I turn on the television, stumble upon a professional bowling tournament, and see guys for whom not bowling a strike is a rare occurrence. The difference between amateur and professional bowlers is huge. The difference between investment amateurs and investment professionals can be just as huge. But you can close much of that gap with ETFs.

Consider a few impressive numbers

By investment professionals, Lord knows I’m not talking about stockbrokers or variable-annuity salesmen, or my barber, who always has a stock recommendation for me. I’m talking about the managers of foundations, endowments, and pension funds with $1 billion or more in invested assets. By amateurs, I’m talking about the average U.S. investor with a few assorted and sundry mutual funds in their 401(k).

Let’s compare the two: During the 30-year period from 1990 through to the end of 2020, the U.S. stock market, as measured by the S&P 500 Index, provided an annual rate of return of 10.7 percent. Yet the average stock fund investor, according to a study by the Massachusetts-based research firm Dalbar, earned an annual rate of 6.24 percent over that same period. The Bloomberg-Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index earned 5.86 percent a year over that same period, while the average bond fund investor earned but 0.45 percent.

Why the pitiful returns? Although there are several reasons, here are three main ones:

- Mutual fund investors pay too much for their investments.

- These investors jump into hot funds in hot sectors when they’re hot and jump out when those funds or sectors turn cold. (In other words, they are constantly buying high and selling low.)

- Small investors panic easily, and all too often cash out when the going gets rough.

Professionals tend not to do those things. To give you an idea of the difference between amateurs and professionals, consider this: For the 10-year period ended December 31, 2020, the average small investor, per Dalbar, earned a 4.9 percent annual return on their investments. Compare that to, say, the endowments of MIT (11.4 percent), Yale (10.9 percent), or Dartmouth (10.4 percent).

You can do what they do!

Professional managers, you see, don’t pay high expenses. They don’t jump in and out of funds. They know that they need to diversify. They tend to buy indexes. They know exactly what they own. And they know that asset allocation, not stock picking, is what drives long-term investment results. In short, they do all the things that an ETF portfolio can do for you. So do it. Well, maybe…but first, read the rest of this chapter!

Passive versus Active Investing: Your Choice

Surely, you’ve sensed by now my preference for index funds over actively managed funds. For the first years of their existence, all ETFs were index funds.

On March 25, 2008, Bear Stearns introduced an actively managed ETF: the Current Yield ETF (YYY). As fate would have it, Bear Stearns was just about to go under, and when it did, the first actively managed ETF went with it. Prophetic? Perhaps. In the years since, hundreds of actively managed ETFs have hit the street. Many have died. Today, there are 586, but they are not enjoying enormous commercial success. At the time of this writing, active ETFs, per Morningstar Direct, accounted for a very measly 2.8 percent of the nearly $7 trillion invested in ETFs.

According to Cerulli Associates, however, the majority (79 percent) of U.S. ETF issuers, as of end of year 2020, were either developing or planning to develop active ETFs.

I don’t think the advent of actively managed ETFs is necessarily a bad thing, but I’m not frothing at the mouth to invest in actively managed ETFs, either.

Let’s looks at a few of the pros and cons of index investing versus investing in actively managed funds, and then let’s look at how the ETF wrapper throws a wrinkle into the equation.

The index advantage

The superior returns of indexed mutual funds and ETFs over actively managed funds have had much to do with the popularity of ETFs to date. As discussed, the vast majority of ETFs — 77 percent in terms of actual numbers, and nearly 98 percent in terms of assets — are index funds (which buy and hold a fixed collection of stocks or bonds). And, as index funds, they can be expected to outperform actively managed funds rather consistently. According to Standard & Poors SPIVA Scorecard, 88 percent of large-cap core stock funds underperformed their benchmark index in the past five years. High yield bond funds? Ninety-five percent underperformed. Flipping that around, only 5 to 12 percent of actively managed funds succeeded at beating the index funds.

Here are some reasons why index funds (both mutual funds and ETFs) are hard to beat:

- They typically carry much lower management fees, sales loads, or redemption charges.

- Hidden costs — trading costs and spread costs — are much lower when turnover is low.

- They don’t have cash sitting around idle (as the manager waits for what they think is the right time to enter the market).

- They are more — sometimes much more — tax efficient.

- They are more “transparent”; you know exactly what securities you are investing in.

According to a study done by Credit Suisse, of all the funds in America — both mutual funds and ETFs — 27 percent are true index funds, 58 percent are actively managed funds, and a full 15 percent are closet index funds, meaning they invest as an index fund would, but charge what an active fund would.

When you get to Chapter 25, I’ll fill you in on how you can readily recognize — and avoid! — purchasing a closet index fund.

The allure of active management

Speaking in broad generalities, actively managed mutual funds have been no friend to the small investor. Their persistence remains a testament to people’s ignorance of the facts and the enormous amount of money spent on (often deceptive) advertising and PR that give investors the false impression that buying this fund or that fund will lead to instant wealth. The media often plays into this nonsense with splashy headlines, designed to sell magazine copies or attract viewers, that promise to reveal which funds or managers are currently the best.

Still, active management can make sense — and that may be especially true when some of the best aspects of active management are brought to the ETF market and some of the best aspects of ETF investing are brought to active management.

Some managers actually do have the ability to “beat the markets,” but they are few and far between, and the increased costs of active management often nullify any and all advantages these market-beaters have. If those costs can be minimized, and if you can find such a manager, you may wind up ahead of the game. Actively managed ETFs cost more than indexed ETFs, but they are cheaper than actively managed mutual funds.

Active management in ETF form may also be both more tax efficient and more transparent than it is in mutual fund form. “Transparent” means you get to see the manager’s secret sauce. Active managers like to keep their secret sauce, well, secret. To date, this has been easier when the wrapper has been a mutual fund, rather than an ETF. However, this may not continue to be the case, as the active managers have already gotten okay from the SEC for partial intransparency and are busy petitioning the SEC to allow yet more smoke.

And finally, with some kinds of investments, such as commodities and micro cap stocks, active management may simply make more sense in certain cases. I talk about these scenarios in Parts 2 and 4.

Why the race is getting harder to measure…and what to do about it

Unfortunately, the old-style “active versus passive” studies that consistently gave passive (index) investing two thumbs up are getting harder and harder to do. What exactly qualifies as an “index” fund anymore, now that many ETFs are set up to track indexes that, in and of themselves, were created to outperform “the market” (traditional indexes)? And whereas index investing once promised a very solid cost saving, some of the newer ETFs, with their newfangled indexes, are charging more than some actively managed funds. Future studies are only likely to become muddier.

Here’s my advice: Give a big benefit of the doubt to index funds as the ones that will serve you the best in the long run. If you want to go with an actively managed fund, follow these guidelines:

- Keep your costs low.

- Don’t believe that a manager can beat the market unless that manager has done so consistently for years, and for reasons that you can understand. (That is, avoid “Madoff” risk!)

- Pick a fund company that you trust.

- Don’t go overboard! Mix an index fund or two in with your active fund(s).

- All things being equal, you may want to choose an ETF over a mutual fund. But the last section of this chapter can help you to determine that. Ready?

Do ETFs Belong in Your Life?

Okay, so on the plus side of ETFs, you have ultra-low management expenses, super tax efficiency, transparency, and a lot of fancy trading opportunities, such as shorting, if you are so inclined. What about the negatives? In the sections that follow, I walk you through some other facts about ETFs that you should consider before parting with your precious dollars.

Calculating commissions

I talk about commissions when I compare and contrast various brokerage houses in Chapter 3, but I want to give you a heads-up here: You may have to pay a commission every time you buy and sell an ETF. But, as I’m writing these words, another brokerage house may have eliminated commissions altogether.

Trading commissions for stocks and ETFs (it’s the same commission for either) have been dropping faster than the price of desktop computers. What once would have cost you a bundle, now — if you trade online, which you definitely should — is really pin money, perhaps a few dollars a trade, and increasingly, nothing at all. So, unless you are investing a very small amount of money, you needn’t worry about commissions anymore. They are the smallpox of Wall Street.

Moving money in a flash

The fact that ETFs can be traded throughout the day like stocks makes them, unlike mutual funds, fair game for day-traders and institutional wheeler-dealers. For the rest of us common folk, there isn’t much about the way that ETFs are bought and sold that makes them especially valuable. Indeed, the ability to trade throughout the day may make you more apt to do so, perhaps selling or buying on impulse. As I discuss in detail in Chapter 22, impulsive investing, although it can get your endorphins pumping, is generally not a profitable way to proceed.

Understanding tracking error

At times, the return of an ETF may be greater or less than the index it follows. This situation is called tracking error. At times, an ETF may also sell at a price that is a tad higher or lower than what that price should be, given the prices of all the securities held by the ETF. This situation is called selling at a premium (when the price of the ETF rides above the value of the securities) or selling at a discount (when the price of the ETF drops below the value of the securities). Both foreign-stock funds and bond funds are more likely to run off track, either experiencing tracking errors or selling at a premium or discount. But the better funds do not run off track to any alarming degree.

In Chapter 3, I offer a few trading tricks for minimizing “off track” ETF investing, but for now, let me say that it is not something to worry about if you are a buy-and-hold ETF investor — the kind of investor I want you to become.

Making a sometimes tricky choice

Throughout this book, I give you lots of detailed information about how to construct a portfolio that meets your needs. Here, I just want to whet your appetite with a couple of very basic examples of decisions you may be facing.

Say you have a choice between investing in an index mutual fund that charges 0.06 percent a year and an ETF that tracks the same index and charges the same amount. Or, say you are trying to choose between an actively managed mutual fund and an ETF with the very same manager managing the very same kind of investment, with the same costs. What should you invest in?

But say you have, oh, $5,000 to invest in your Traditional IRA. (All Traditional IRA money is taxed as income when you withdraw it in retirement, and therefore the tax efficiency of securities held within an IRA isn’t an issue.) In this case, I’d say that the choice between the ETF and the mutual fund is nothing to sweat over. If all else is the same, I’d have a very slight preference for the ETF, if for no other reason than its portability. (See the sidebar, “The index mutual fund trap.”)

And what if your brokerage still charges a commission? Avoid it by going with the mutual fund (provided the mutual fund doesn’t cost you a commission). What if there’s a difference in management fees between the two funds? Say, an ETF charges you a management fee of 0.10 percent a year, and a comparable index mutual fund charges 0.15 percent, but buying and selling the ETF will cost you $5 at either end. Now what should you do?

The math isn’t difficult. The difference between 0.10 and 0.15 (0.05 percent) of $5,000 is $2.50. It will take you two years to recoup your trading fee of $5. If you factor in the cost of selling (another $5), it will take you four years to recoup your trading costs. At that point, the ETF will be your lower-cost tortoise, and the mutual fund your higher-cost hare.

If you, like me, are not especially keen on roller coasters, then you are advised to put your nest egg into not one stock, not two, but many. If you have a few million sitting around, hey, you’ll have no problem diversifying — maybe individual stocks are for you. But for most of us commoners, the only way to effectively diversify is with ETFs or mutual funds.

If you, like me, are not especially keen on roller coasters, then you are advised to put your nest egg into not one stock, not two, but many. If you have a few million sitting around, hey, you’ll have no problem diversifying — maybe individual stocks are for you. But for most of us commoners, the only way to effectively diversify is with ETFs or mutual funds. I’m astounded at what some funds charge. Whereas the average active fund charges between .51 (for ETFs) and 0.63 percent (for mutual funds), I’ve seen charges five times that amount. Crazy. Investing in such a fund is tossing money to the wind. Yet people do it. The chances of your winding up ahead after paying such high fees are next to nil. Paying a load (an entrance and/or exit fee) that can total as much as 6 percent is just as nutty. Yet people do it.

I’m astounded at what some funds charge. Whereas the average active fund charges between .51 (for ETFs) and 0.63 percent (for mutual funds), I’ve seen charges five times that amount. Crazy. Investing in such a fund is tossing money to the wind. Yet people do it. The chances of your winding up ahead after paying such high fees are next to nil. Paying a load (an entrance and/or exit fee) that can total as much as 6 percent is just as nutty. Yet people do it. There have been times (pick a bad year for the market — 2000, 2008,…) when many mutual fund investors lost a considerable amount in the market, yet had to pay capital gains taxes at the end of the year. Talk about adding insult to injury! One study found that over the course of time, taxes have wiped out approximately 2 full percentage points in returns for investors in the highest tax brackets.

There have been times (pick a bad year for the market — 2000, 2008,…) when many mutual fund investors lost a considerable amount in the market, yet had to pay capital gains taxes at the end of the year. Talk about adding insult to injury! One study found that over the course of time, taxes have wiped out approximately 2 full percentage points in returns for investors in the highest tax brackets. R squared is a measurement of how much of a fund’s performance can be attributed to the performance of an index. It can range from 0.00 to 1.00. An R squared of 1.00 indicates a perfect match: When a fund goes up, it’s because the index was up — every time; when the fund falls, it’s because the index fell — every time. An R squared of 0.00 indicates no such correlation. This measurement is used to assess tracking errors and to identify closet index funds.

R squared is a measurement of how much of a fund’s performance can be attributed to the performance of an index. It can range from 0.00 to 1.00. An R squared of 1.00 indicates a perfect match: When a fund goes up, it’s because the index was up — every time; when the fund falls, it’s because the index fell — every time. An R squared of 0.00 indicates no such correlation. This measurement is used to assess tracking errors and to identify closet index funds.