64 Roles

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

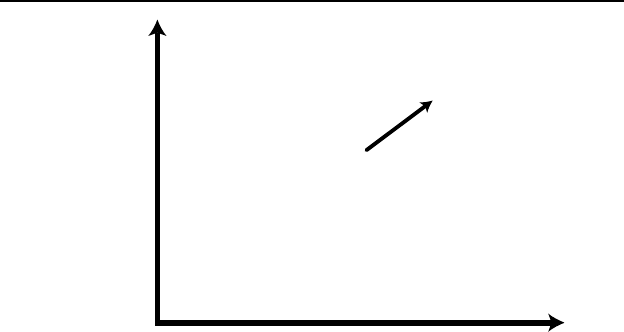

FIGURE 3.4

The Dual Concerns Model

Uncooperative (Low)

Assertive

(High)

Degree of Attempt to Satisfy Others’ Concerns

Unassertive

(Low)

Cooperative (High)

Avoiding

Competing

Accommodating

Compromising

Degree of

Attempt to

Satisfy One’s

Own Concerns

Collaborating

For a multi- level learning coach, it is important to help people move

beyond these initial positions to identify, understand, and satisfy the un-

derlying needs that give rise to them. When the underlying needs are un-

derstood, and each party agrees on what those needs are, it is possible to

reframe the problem from the initial positions to nd a solution that meets

each party’s underlying needs. The IT department’s position might be that

it needs more people from the call center to test its new software appli-

cation, while the call center manager’s position might be that she can’t

provide more people because their time needs to be dedicated to serving

customers. Reframing helps people move beyond these initial positions

to meet the underlying needs that generated them in the rst place. The

problem can then become, “How can we satisfy the IT group’s need to

ensure that the new software application for the call center is free of ‘bugs’

and, at the same time, enable the call center to maintain the high levels of

service that customers expect while the software is being tested?” This can

lead to more creative solutions than those available by bargaining over the

initial positions. For example, the two groups might agree to move up the

software implementation so that it does not coincide with a peak time for

customer service, enabling IT to get the people it needs for testing while

enabling the call center to meet its service- level goals at the same time.

The Multi-Level Learning Coach 65

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

The multi- level learning coach can intervene by helping people fo-

cus on how their behaviors might create a win- lose situation, or one in

which someone caves in for fear of asserting her needs. Ellen Raider,

Susan Coleman, and Janet Gerson (Raider et al., 2006) o er a simple yet

useful mnemonic tool, AEIOU, that helps to distinguish between produc-

tive and nonproductive behaviors in con ict situations. Each letter signi-

es the rst letter of a type of behavior that is typical in these situations.

Starting with the rst, attacking behaviors include threats, hostile words

or gestures, insults, defending, criticizing, interrupting, and asking judg-

mental questions, to name a few. These often lead to escalation of the

con ict rather than resolution. Evading behaviors are also unproductive,

and include changing the subject, withdrawing, postponing, or not ac-

knowledging the issues to begin with. Informing behaviors can be useful,

because they enable people to state their needs and justify their positions

with facts. Informing behaviors should be used to help others understand

the information being conveyed, enabling valid information to be shared

and mutually understood. The next two types of behaviors—opening

and uniting behaviors—are highly productive and generally lead to suc-

cessful collaboration. Opening behaviors enable people to uncover the

underlying needs of others. These include asking nonjudgmental ques-

tions about the other’s position, needs, or feelings; actively listening by

paraphrasing what was heard; and testing understanding and summariz-

ing without necessarily agreeing. Uniting behaviors are also important

because they not only bring people and perspectives together to set a tone

that enables the sharing of underlying needs in a way that’s suitable for all

involved, but also enable joint solutions to be developed and relationships

to continue in collaborative ways after resolution of the con ict. Uniting

behaviors include ritual sharing to build rapport, establishing common

ground, and reframing a problem to develop solutions that meet both

sides’ needs.

By keeping this simple mnemonic in mind, the multi- level learning

coach can intervene with teams to help them distinguish collaborative be-

haviors from those that more often than not lead to avoidance, blame, or

defensiveness and therefore leave problems unresolved, creating the op-

portunity for continuing frustration and poor performance.

We now turn to the fth and nal component of group process to be

discussed, boundary management.

66 Roles

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

Boundary Management

Groups, whether they be senior management teams, departments, or

project teams, are both di erentiated from and integrated within a larger

social structure consisting of many “communities of practice.” As dis-

cussed in Appendix B, Etienne Wenger, Richard McDermott, and William

Snyder (2002) de ne communities of practice as “groups of people who

share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who

deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an

ongoing basis” (p. 4). Just as groups of disparate people can develop into

teams, so can teams develop into their own “communities of practice.”

Over time, through mutual engagement and joint enterprise, teams can

develop a shared history that includes both tacit and explicit knowledge

in the form of memories and a common repertoire of tools, methods, ar-

tifacts, and language. While communities of practice are highly e ective

at learning and continuously improving, through their work they also dif-

ferentiate themselves from the larger organization. And it is this di eren-

tiation that creates the need to manage “practice boundaries” e ectively,

whether these boundaries lie between management teams and project

groups or between functional groups like IT and marketing. Boundaries

are a natural consequence of learning in communities of practice.

To manage boundaries e ectively, especially for cross- functional

teams that consist of members from multiple communities of prac-

tice, team members and project managers may be required to play a

brokering role. Project managers leading cross- functional projects, for

example, may belong to both a community of project management pro-

fessionals associated with a PMO and a community of engineers within

which their career has progressed. Brokering is the process of establish-

ing connections between communities by “introducing elements of one

practice into another” through processes of translation, coordination,

and alignment between perspectives (Wenger, 1998, p. 105). Translation

involves the rendering of something written or spoken in one communi-

ty’s words into the language and practices used in another. Coordination

involves facilitating connections and transactions between communities

and their members. Alignment involves addressing and resolving con-

icting interests among two or more communities of practice.

The Multi-Level Learning Coach 67

American Management Association

www.amanet.org

Wenger elaborates further on the role and competencies required of

brokers:

It requires enough legitimacy to in uence the development of a prac-

tice, mobilize attention, and address con icting interests. It also re-

quires the ability to link practices by facilitating transactions between

them, and to cause learning by introducing into a practice elements of

another. (Wenger, 1998, p. 109)

Multi- level learning coaches can help members become e ective bro-

kers not only by helping them understand the nature of communities of

practice as described in Appendix B, but also by reinforcing the tools of

e ective communication and con ict resolution described earlier in this

chapter. E ective communication tools such as the Ladder of Inference

and the TALK model can help people with di erent perspectives share

their tacit knowledge—the knowledge that exists in their heads in the

form of meanings, inferences, assumptions, and conclusions—which is

di cult to uncover, particularly for those with di erent shared histories

who come from di erent backgrounds. In addition, where con icting in-

terests appear to be at work, con ict resolution and e ective collaboration

are more probable when people seek to identify the underlying needs, re-

frame problems to address these needs, and nd joint solutions that work

for each party involved.

Multi- level learning coaches can not only help teams develop their own

community of practice, but also encourage team members to seek so-

lutions that include perspectives from multiple communities of practice,

leading to more sustainable results and higher levels of collaboration.

Having discussed models for e ective group processes, including com-

munication, problem solving, decision making, con ict resolution, and

boundary management, we now turn to a model for diagnosis and inter-

vention that can guide multi- level learning coaches in their e orts to help

groups learn and re ect in ways that are consistent with these models.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.