3

ABOUT BEEKEEPING

This chapter is going to work from the ground up, starting like you do—with a brand-new package in your brand-new equipment. We’ll shepherd that colony through its first year and into the next season, so next year you’ll have all the information you need to continue.

Start by reading the section on installing a package. Get familiar with the sequence of events before you begin. Installing a package is a simple process and difficult to bungle. However, it can be a bit nerve-racking the first time.

LIGHTING YOUR SMOKER

Your smoker, hive tool, and protective gear are all tied for first place as need-to-have beekeeping tools. But you also have to light and keep your smoker lit. If it goes out when you take your colony apart, you’ll need to retreat to relight. Meanwhile, your colony stands open and unsecured.

Lighting a smoker is similar to starting a campfire or a fire in a fireplace. Start with rapidly burning, easily combustible tinder. Newspaper is perfect and readily available. Once it is burning and pushed to the bottom of the smoker, add less-flammable but more durable material and establish that, pumping the bellows slowly to push the flame up into the newly added fuel while at the same time develop a bed of coals that will sustain the fire and not go out. Then, if needed, finish with longer-burning fuel that will sustain the fire. The following nine-step process works every time.

There are two tests you must pass with your smoker. The first is that your skills need to evolve to the point that your smoker will not go out after 10 minutes without puffing. If it does, you didn’t prepare the fuel correctly. Practice and more practice will enable you to prepare your smoker for a half hour without puffing. The second test is the temperature of the smoke. At any time, you should be able to hold your hand over the opening, puff, and not have hot smoke emerge. It should always feel comfortable to the skin. If it is too hot, you will singe bees, an unhappy occurrence for all concerned. If it is hot, stop, close up the hive and add more fuel (you have some handy, right?). If unavailable, add large handfuls of green grass or leaves to keep the smoke cool.

When you finish using the smoker, empty its contents on a fireproof surface, making sure the coals are out. Use caution: sometimes, when you dump out the fuel in your smoker, it will burst into flame because of the sudden availability of oxygen. This can catch you or other flammable material on fire very quickly. Some beekeepers use a dedicated small trash can with a lid to dump the residue in. They dump it in and replace the cover quickly so any smoldering fuel is quickly extinguished. Even if it’s not, the container keeps any fire in place and safely away. You can also lay the smoker on its side; without a draft from bottom to top, it will quickly go out. Still lit or still very hot smokers can cause fires if placed too close to flammable material. Make sure it’s empty and cool before putting it away.

Occasionally check the smoker’s intake air tube on the bottom to make sure it is clear and scrape out the inside of the funnel. Accumulated ash and creosote will slowly close the opening.

If sparks from the fire are coming out of the spout, check your fuel because it may be nearly gone. If the fuel is still plentiful, grab a handful of grass or leaves and put it on the top of the fuel inside to stop the sparks.

Never aim your smoker at someone and puff. Besides causing the inhalation of smoke and limiting sight, flying sparks may ignite clothing or melt plastic veil material. Also, use smoke sparingly on your bees. A little bit goes a long, long way.

Step 1: Assemble your tools: paper, pine needles (my fuel of choice), punk wood, matches, and smoker. Smoker fuel depends to a degree on where you live. If long-needled pines are numerous, your fuel issue is solved. But people use wood shavings, cotton waste sold by bee supply companies, wooden pellets, untreated burlap or twine, sawdust, or almost anything that’s combustible and does not contain pesticides or petroleum products.

Step 2: Crumple the newspaper into a loose ball that doesn’t quite fit into the smoker and light the bottom, and once lit, let it rest on the rim of the smoker as it continues to burn.

Step 3: Let the paper catch fire and the flame begin to move up without it reaching your hand. Push the paper to the bottom of the smoker using your hive tool and puff the bellows gently two or three times to keep fresh air moving past the burning paper. It will flame up to or just over the edge of the top of the chamber.

Step 4: Puff two or three times more until most of the paper is burning—but not yet nearly consumed—and add a pinch of pine needles or other fuel to the top. Don’t stuff them in, just let them fall in.

Step 5: Puff several more times until the flames from the paper reach up and catch the needles afire. Once they are burning well, push the burning needles down into the chamber with your hive tool, puffing slowly so air moves through the system.

Step 6: When the first small batch of needles flames up, add a bigger pinch of pine needles, loosely. Puff several times so you don’t smother the fire. Keep air moving through the system. This is when most lighting attempts fail because too much fuel was added, so no air is available from the top and not enough is coming up from the bottom. The smoldering needles starve for oxygen and the fire dies.

Step 7: When the fourth or perhaps fifth small batch of needles has been added, puffed, and pushed to the bottom and begins to smoke from the bottom, and it smokes and burns without being puffed, add one or more larger batch. Push this fuel down first with your hive tool, then with your clenched fist so the cylinder is about half full of compressed fuel. Keep pumping. The coals should be far enough below the top that your hand will not be uncomfortable. Push fairly hard until the fuel no longer collapses. Then add the more durable fuel, if needed, on top of the needles. Keep puffing slowly to keep air in the system.

Step 8: When lots of smoke rises when you puff, and if the fire doesn’t quit when you don’t puff for a minute or so, close the smoker, still puffing occasionally.

Step 9: When lit, the smoker should smolder unattended for up to a half hour or more. If it sits idle for a while without use, puff rapidly a couple of times so the smoldering coals flare up a bit, producing lots of cool, white smoke to waft over the bees.

PACKAGE MANAGEMENT

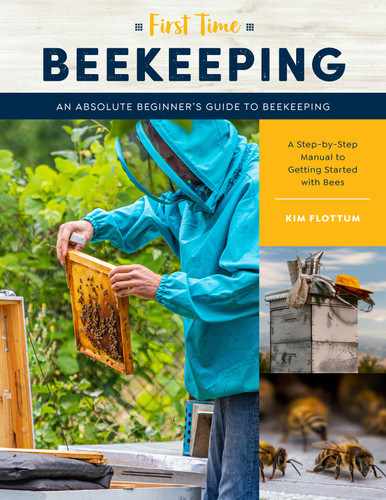

Almost all beekeepers get their first bees from a business that sells packages. Bees are sold by the pound, and the most common size container has 3 pounds (1.4 kg) of bees. With about 3,500 bees in a pound, a 3-pound (1.4 kg) package (the most common and most recommended) contains roughly 10,000 bees. Almost all are workers who have been removed from a single colony and placed in the package. Then, a queen not from that colony, in her cage, is added to the package, a feeder can put in its slot, and the top covered.

If you have to order your bees by mail, arrange with the supplier to have them arrive midweek so they don’t sit in a post office over a weekend. Make sure the package producer displays your phone number (home, work, or cell phone for daytime messages) prominently on top of the package, with instructions to call you immediately when the package arrives at your local post office. Remember to inform the post office that you must retrieve the package immediately. Some post offices will store it in an out-of-the-way place, such as a loading dock or storage room. Unfortunately, these places can be too warm, too cold, in a draft, or in direct sunlight, any of which can be lethal to the bees if held there too long.

Another package container you may encounter is made of plastic. This design is still in development, but it has some advantages over the older model. Like the wood-and-wire cage, there is an opening to place the feeder container in, but the inside bottom of the feeding container blocks the opening so it needs no cover. Depending on the model you get, the queen will be suspended inside next to the feeding container just like the older model, or there may be a place on the top of the package the queen cage simply lies in so the bees inside can reach her through the mesh from the inside. But you don’t have to remove the feeding container first to get to the queen. You will need a way to introduce the queen cage into the hive if this is the case as there will be no wire or other means included with the cage. That’s why you brought the rubber bands. The feeding container may be a simple tin can holding syrup or it may be a plastic container filled with a fondant-like material. Again, depending on the model, one end may open to release the bees, or you may have to pour them out through the top opening. You’ll need one more thing if you have one of these: a square of cardboard or plywood large enough to cover the hole created when the feeder can inside is removed. You’ll need to get the queen out before you release the bees and make sure the bees stay in the cage when the can is removed.

You may get a plastic container as a feeder can. It will contain sugar jelly or fondant for feeding the bees during their journey from old home to new. I suggest not using this after placing the bees in their new home and stick with using sugar syrup.

Of course, you should get the bees into their new home as soon as you can. That may be just an hour or two, or a day or two, depending on your schedule and the weather. Cool, rainy weather is tolerable, but very cold temperatures—below 40°F (5°C)—are probably colder than you want, so wait a day. While waiting, keep your package in a cool, dark place, such as the basement or garage. Put down a couple sheets of newspaper to keep the floor clean.

You’ll also need to feed the bees. Get a new, unused spray bottle (such as those used for misting plants) and mix up a sugar-water solution of one-third sugar to two-thirds water by volume, that is, 1 cup (235 ml) white sugar mixed with 2 cups (475 ml) warm water. As soon as possible, on the way home even, spray some of this solution through the screen directly onto the bees through the screen or plastic mesh. Don’t saturate them but moisten as many bees as possible through all open sides of the package. Do this at least a couple of times a day as long as they are in storage. If you will be forced to hold them any time before installing them, check the feeder can, which could be plugged or empty. To do this, remove the cover if there is one and, using your hive tool or fingers, lift it a tiny bit to see if it has weight. If it does, but bees aren’t on the bottom feeding, the holes may be plugged and you will have to feed them. If empty, do the same. Don’t ever assume they have food available.

The traditional package made of wood and screen, with a tin can suspended inside along with a queen. There are typically 3 pounds (1.4 kg) of honey bees inside, with a queen. The bees hang around the queen, who is suspended inside the package next to the tin can that holds sugar syrup. The package has a cardboard or plywood cover on top, keeping the can, the queen, and the bees in place. A few dead bees will be on the bottom of the cage; if there is a 1/2” (1.3 cm)-thick layer, or more, contact the supplier. To hold these packages together, the sender must use a wooden strap nailed to the packages. Though not difficult to remove, you’ll need the right tools to do so if you have more than one package.

You’ll also need to feed protein. New packages need both, though you will seldom hear beekeepers discuss this. Bees do not live on sugar alone. You can feed your new bees protein a couple of different ways, inside and outside the colony. Initially, a patty inside is recommended as it is close and easy. However, small hive beetles like these patties even better than your bees, so be aware of them when checking the colony. If you note small hive beetle larvae present in the patty, remove and destroy it.

Use a mister bottle to put sugar syrup on the screen so the bees have food. Use a new bottle, and don’t soak the bees when misting.

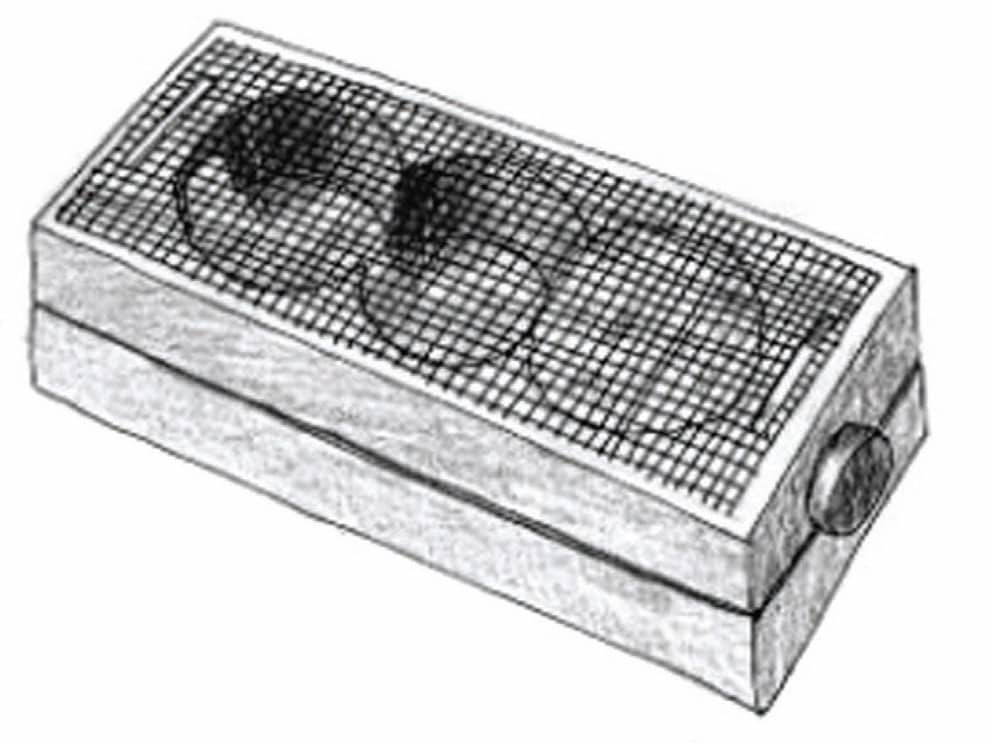

A queen cage is shown here, along with the fondant candy and cork in place. This is typically called a three-hole cage and is common in packages, but it’s not necessarily the only type you will see.

Local suppliers drive to the package producer and pick up packages directly, reducing the delivery time and the stress on the bees. You can get packages either with a queen or without one and install the one you want later. Bees are a commodity, but the queen is the future of your colony. Don’t settle for just any queen.

You can also feed protein supplement powder outside, placed nearby in a container on its side to shelter it from the weather. Your bees will find it and gather it like pollen.

Bees do not conserve food. The bees in the cage will eat as much as they can when hungry and there is no regulating body who says, ‘Slow down girls. We don’t know where our next meal is coming from and if we run out, we’re in trouble.’ The bees simply eat until it’s all gone, and then they all starve. If that occurs, you will see your package looking just fine before you go to bed and find 4 inches (10 cm) of dead bees on the bottom when you get up the next morning. It is dramatic, destructive, and absolutely preventable.

IN THEY GO!

To begin, use your spray bottle to give the package a feeding. Then, take all your equipment out to the site and get it set up. Put the bottom board on your hive stand and one super with frames intact on top of that. Leave the next two supers, without frames, stacked alongside and one super with frames intact. (You need four supers, the bottom one with bees, a second one with just frames and perhaps the queen, and, if using medium supers, two more without frames to cover the feeders.) Don’t forget the inner and outer covers. Prepare the sugar syrup for the feeder pail with a two-to-one (2:1) water–sugar solution. Fill the pail to the very top, and make sure the lid is secure. Refill your spray bottle at the same time.

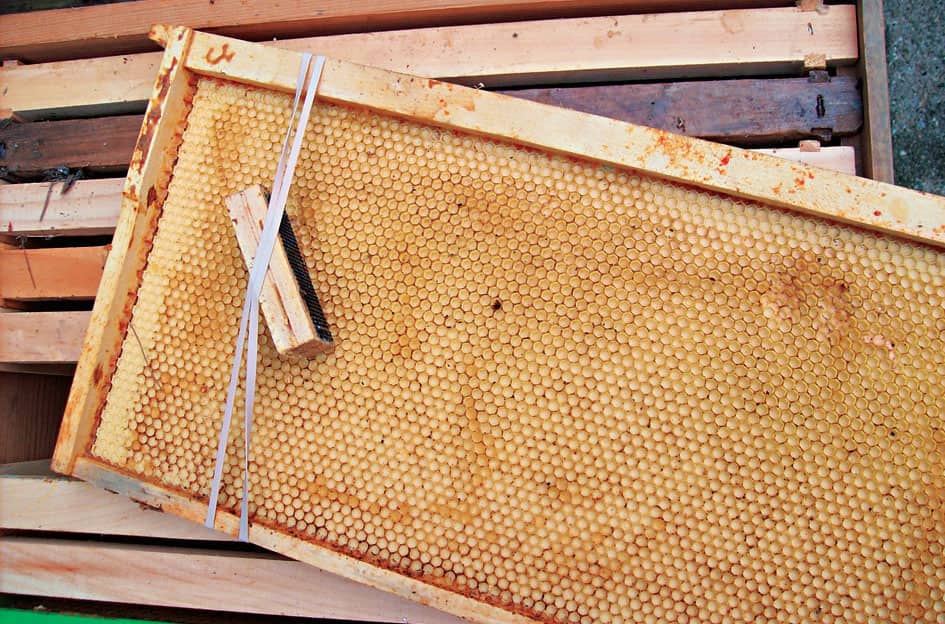

If all your equipment is new, your frames will have only foundation, either wax or wax-coated plastic. If you have combs from other equipment, place those in the center of the eight frames in the box. (Be certain, however, that the colony from which these frames came was disease free.)

Put on your protective gear, light your smoker (you probably won’t need this, but be prepared), make sure you have your hive tool and pliers, and bring your package to the hive site. If you want, bring a board large enough to fit securely on your hive stand to serve as a solid, dry working surface, but only if the hive stand is long enough to hold both the colony and the board, with a little room to spare. Otherwise, place the board on the ground close to the back of the colony’s entrance.

Remove the cover, inner cover, and the middle six frames from the eight-frame box that sits on the bottom board, or the middle eight frames if you are using a ten-frame box. Set the cover, inner cover, and frames behind the box or to the side. If you are installing more than one package, prepare all the boxes at the same time.

Position yourself behind the colony into which you plan to install the bees. Make sure you have all your tools—smoker, hive tool, and feeder. Set the package on the board, and using your hive tool, remove the cover if there is one. You may also need pliers for this. Remove any protruding nails or staples and keep the cover close at hand because you will need it again in a few moments (this is for the wood and wire packages).

(1) Make sure you have a good hold on the can before thumping the cage. If not, it may fall off the support below, if there is one.

(2) Remove the queen’s cage carefully. Don’t drop her, if you can help it. Don’t let the bees unnerve you. Gently shake or blow them off the cage.

(3) When the queen’s cage is free of worker bees, put it in your pocket to keep her warm and for safekeeping.

(4) Quickly and carefully dump the bees into the space created by the missing frames. Shake the bees a bit to get them to come out, but don’t worry about every last bee. You’ll get them later.

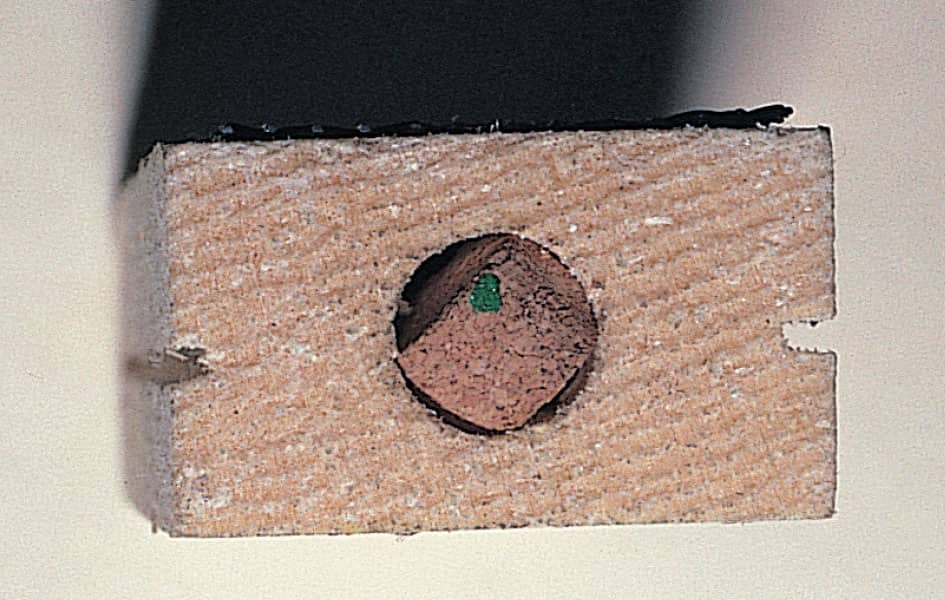

(5) If your queen cage comes equipped with a hook or wire, loop it over a top bar, off center, and hang the cage so the screen faces the opening between frames. Seriously consider securing it to the top bar with duct tape or a staple. You can’t be too careful with a bug as expensive as a queen. The tape will make sure your queen stays where she should. If there isn’t a wire or tab, and often there isn’t one that works for installing in a package, use rubber band to hold the cage in essentially the same location. See the photos for proper installation with this technique.

(6) If you are lucky and have drawn comb in the frames in the box above the box you dump the bees into, install the queen in the upper of two boxes. The queen’s cage should be placed between frames in the top box, with the screen facing down, and the cage actually resting on the lips of the bottom bars. Gently squeeze the two frames together so the queen cage becomes just a bit embedded in the wax comb on each side. This will securely hold the cage in place until she is released. This won’t be possible if this is your first colony and you don’t have drawn comb already, but it is very useful if you do.

(7) Put the inner cover on top of the bottom box with the bees and put the two frameless boxes on top of the inner cover and place the feeder pail over the hole in the inner cover. You’ll need two medium supers to enclose the pail. Cover these boxes with the outer cover. If you put the queen in the second box from the bottom this won’t work. Use an additional box to accommodate the queen, plus feeders.

Take a look at the opening underneath the cover or simply look at the top of the package. You’ll see the top of the feeder can, flush with the surface of the package top. There may be a slot cut in the top with a metal strip in it. This strip is fastened to the queen’s cage, which is suspended below in the mass of bees. However, the cage may be held in place with a metal strap tight to the feeder can, or it may be a round disk that holds the cage from above. How you suspend the queen’s cage in your hive will vary, depending on which of these devices is used by the package producer.

Installation of the BeeBus: Lightly spray the bees with a 1:1 sugar syrup so they are distracted and busy cleaning up. Remove the queen in the same manner as the older package and keep her in your pocket. Then, close the feeder can opening with the slide door if it has one, or place a simple piece of cardboard or plywood held in place by a couple of short nails, duct tape or rubber bands. Then, lay the package on its side, so that when the opening on the end is opened, the side panel opens down. Using your hive tool, unfasten the two snaps that hold the end open, but don’t open it yet. Inside, there is a support for the feeder attached to the bottom of the package. Turn the package over so it is laying on its side, with the opening on the end such that the hinge is on the bottom, as in the photo. Once there, lift the end opposite the now-open end two or three inches (8 cm) off the ground and thump it down. This will dislodge all the bees from the top and sides to the bottom (you may have to do this a second, or even third time). Holding the package, move it to your open colony, open the end and simply slide the bees into the waiting opening in the hive. Finish by getting the queen into the colony if not already, closing it up and getting food to the bees.

Lightly mist the bees with the sugar water again. Using the corner of your hive tool or your fingers, lift the feeder can about halfway. Some are easy to catch and lift, but some will be a bit below the surface and more difficult to grasp. If you simply can’t catch it, try lifting just a bit and grasping with the pliers. Hold it with the pliers and grab with your other hand.

Leave the paper on the pollen patty to keep it from drying out but score it with your hive tool so the bees have easy access. Watch for small hive beetle larvae after a few days and remove and destroy if you find them.

Next, still holding the can in one hand, lift the package and thump it on the board, hive stand, or simply the cover resting on the ground so all the bees clinging to the feed can and queen cage let go and fall to the bottom. Don’t worry—they’re covered in sugar syrup and don’t care one bit. Try lifting and moving the package to make sure you have a secure grip. When comfortable, lift the package 1' (30.5 cm) or so and thump again. Lift out the can, set it on the board, and slide out the queen’s cage—without dropping her back into the mass of bees on the bottom—and quickly cover the hole in the package with the original cover or the one you brought. Check to make sure the queen is alive and moving, and then put her cage into your pocket to make sure she stays warm. Once removed, you will be able to see how you can fasten her cage to a frame, with a metal strap, wedged into existing comb, or with a rubber band. If needed, have those rubber bands at the ready.

Check to make sure the frames have been removed and that you have placed the wooden entrance reducer in the entrance into which you are going to dump the bees. Make sure the box that is going to go on top of the bottom box is close by, along with the inner cover that will go on the new colony.

Depending on the type of package you have—plastic or wood—you’ll proceed one of two ways. If plastic, pry open the end using a hive tool or screwdriver. Hold it closed. When you’re ready, you’re going to thump the package again, then remove the feeder can, open the end and pour the bees into the cavity in the space created in the box when you removed frames. Pour as many as you can—shake them a little, but not much—and set the package, still containing a few bees, in front of the colony. If you have the standard wood-and-screen cage, thump again, remove the can cover and the can and pour the bees out of this opening into the cavity in the hive. This action will put some bees in the air, but don’t be concerned. They are homeless, very confused, and unlikely to cause you harm.

Carefully lower the frames you removed into the bottom box. Let them slowly sink as the bees on the bottom are gently moved aside to make room for the frames.

Three criteria for inserting a queen cage are: easy access to the queen cage by the hive bees, being securely held, and out of the way of the feeder (if it leaks). The more care you take in introducing your new queens, more food, and less interaction with bees they aren’t familiar with, the greater the probability they will be accepted.

If you place her in a second box between frames, hold the frames secure, and place this box on the box with all the workers. No matter where she is, place a pollen substitute patty directly on the top bars of the second box to one side of the inner cover hole before replacing the inner cover or putting on the hive top feeder. Leave the paper on so it doesn’t dry out but score the paper with four or five cuts on both sides to make access easier. Replace the inner cover, position the feeder if you are using a pail over the inner cover hole or feeder jars on the inner cover, and cover these with the extra super you brought. Or, put on the hive top feeder and the inner cover and close the colony.

FIRST INSPECTIONS

There are many recommendations on how often to inspect your colony, especially a new package. (Checking the amount of available sugar syrup and protein patty doesn’t count as a visit.)

Do not remove the covering from the candy end of the queen cage for at least five days.

After the package has been installed, you must wait patiently. Watch the front door for activity, make notes, take pictures, watch more, and be patient. Be more patient. Check the food situation on top, but don’t worry about the pollen patty yet.

After five days, open the colony carefully, using as little smoke as possible. Put a single puff into the front door. Then, lift the cover and put in a puff. Wait a couple of minutes. Remove the cover and look into the box with the feeder or the top feeder. Puff a couple of times to move bees out of the way. Take the box off, remove the feeder, and puff into the hole in the inner cover. Wait a minute. Lift the inner cover on the end, a couple of inches (cm), and puff a couple of times. Replace. Wait a minute. Remove the inner cover and puff a couple more times to move bees away from the top of the top bars. Now, peer between the frames and see what the bees are doing around the queen cage. Are there lots of them hanging on tightly? Or are they milling around, moving over and around the cage? Then, remove the cage, either by lifting the frame with the cage banded or taped to it, or simply lift the cage out using the hanger. See if she is alive and moving, then gently lay her cage on the top bars, screen side up, and observe. Do bees rush to the cage, and grab it tightly? Do they walk around and over the cage, and then walk away? Do some stay, touching with antennae, feeding the queen? Or do they cover the screen and holes and look as if they are trying to smother the queen? Let this go on for a few minutes. Be patient and do not use smoke.

This is what you might see when the workers are still aggressive toward the queen. They cling tightly to the cage, biting the wires and are difficult to push or blow away because they are trying to get at the new queen.

This is comfortable behavior—the bees aren’t clinging to the cage or biting the wire. Queen release now is safe.

When it is time, remove the cork on the candy end of the cage. Use the corner of your hive tool. Don’t remove the cork on the other end or the queen will walk out prematurely. If you have the plastic cage with a tube full of candy, open the cap at the end exposing the candy.

If the behavior seems casual, not urgent, laid back, then you can be relatively certain that the queen and bees have accepted each other and things will go as well as things can go. I know, since you haven’t been doing this how do you tell urgent from casual? Here’s my yardstick. I pick up the queen cage and gently blow on it to remove any adhering bees and put it back. If the cage is immediately covered again, that’s urgent. If they leave it alone, that’s casual. You might try this two or three time, and over a couple of days to get a feel for this. It’s an expensive bug, so take your time and know for sure.

If, however, the bees are still clinging to the cage and the screen, if after being removed they return immediately, you can be fairly certain that they haven’t yet accepted each other and they need more time. Give them a few more days. Check again, and if they’ve settled down (they almost always do), the queen-to-colony relationship has been established. Releasing the queen is the next step.

If the behavior seems friendly, proceed to the next step. Lightly smoke the colony in the area of the queen cage so the bees retreat. Remove the cage and remove the cork from the fondant candy end with the corner of your hive tool or a toothpick or if you have a plastic cage remove the cap covering the tube with the candy. Test the candy with the toothpick to see if it’s hard. If it’s soft, your work here is done. If it’s hard, very gently poke the toothpick through the candy, making a small hole all the way through it. Just be very careful not to jab the queen when you break through.

If you leave your feeder on and the bees come up to feed, they may construct comb that surrounds the feeder and is attached to the sides of the box. This must be cleaned up. Remove the cover and inner cover, smoke the bees with significant smoke to get them away from the comb, remove the feeder, and remove the beeswax comb, fast. Save the wax (it makes good candles, lotions, or wax for coating plastic foundation). Clean it all out, remove and fill the feeder, and replace the box and cover—and don’t leave it alone for so long again.

When complete, replace the cage in the same place, making sure the screen or the tube isn’t covered by any new wax comb that may have been built up around the cage or frame parts. In fact, you’ll often find stray slabs of beeswax comb, so carefully remove them with your fingers or hive tool first. Replace the top box carefully, check the feeder, refill it if necessary, and put everything back together.

If you are using only foundation and your queen cage doesn’t have a wire, metal strip, or metal disk, use rubber bands to hold it to the frame. The candy end of the cage must be up, and as much of the cage’s screen as possible is exposed between frames so the bees in the colony can reach, feed, and touch the queen in the cage.

The queen should be released by the bees in another three days, so plan on checking again. If she’s not, and if the behavior of the workers is still protective rather than aggressive, pull back the screen or remove the whole cover of the plastic cage and let her walk out, heading down between frames. Don’t let her fly away. Close up the colony.

Looking for Eggs

After her release, the queen should begin laying eggs in a few days, at least within a week. After that time, check for eggs. You’ll find them in the center two or three frames, probably near the tops of the frames in the bottom box. Look at all the frames that have some comb built on them if you don’t find eggs in the center. Recall that eggs are tiny, standing straight up on end, and nearly the same color as the new wax—look carefully.

Once the queen is laying eggs, you’re over the first hurdle and don’t need to inspect the broodnest for another ten to twelve days. Make certain the feeder stays full, however. The bees will continue to use the sugar syrup for some time, especially when the weather doesn’t cooperate—a sure thing in the spring—and at night. For much of the first season, the colony is living hand to mouth with little chance to build reserves. The more you can help, the better off they will be. Enough good food, all of the time, for every bee in the bunch is the best insurance you can get. Don’t skimp. Provide more than enough food. If they take it, they needed it. If they don’t, you’re ahead of the game.

So, what if you don’t find eggs? It happens. Look to see if she’s there. In a colony this small, if she is alone and walking around, she will be fairly easy to find. Listen for the telltale buzzing sounds of a queenless colony.

If you find your new queen, even if she isn’t yet laying eggs, close up the colony and give her two more days to start laying. If, after all this, nothing’s happening, something’s wrong and she needs to be replaced.

KEEPING RECORDS

Keeping a log of your colony’s activities and progress isn’t just a good idea, it’s an absolute necessity. Particularly for the first couple of seasons, making notes will force you to attend to the fundamentals, and the notes remain as a record of what happened when. If you have several colonies, some notes will serve for all, but each colony, you will learn, has its own distinct personality requiring similar but different management actions. Even before you get your bees, decide how you will identify your colonies. “The third from the right” doesn’t work after about a week. One good way is to simply number the colony with spray paint on the top of the cover. That way, no matter where the colony is, you will know all about its history. Reviewing your notes before you next open your colony will remind you of actions you need to take, equipment you need to buy, problems you need to check, and what you should expect to find.

Keep records in a large notebook that is difficult to misplace. After a few seasons, your notes will be minimal because you will have mastered the routine management skills, noting only swarming dates, new queens added, medication applications if used, and the amount of harvest.

There is no substitute for keeping good records. Get a good notebook or a three-ring binder. Designate one page for every colony (spray paint a number on the cover of each colony, too). Or, create a page for every visit to the beeyard, and keep dated notes on each colony visited on each page.

OPENING A COLONY

The first few times you examine a colony can be exciting, scary, and confusing. It’s easy to get sidetracked and forget to do one of your planned tasks. Before you get started, make a mental note of why you are looking inside. This is good advice whenever you are going to examine your colony. Check your record book first, always. When you know why you’re going in, you’ll know what you need to do the job, so get everything together and bring it with you.

Before you begin, make doubly certain your smoker is burning well, but give it a reassuring puff every few minutes, just to be sure. If you’re feeding, have your extra feeder full and ready. Bring supers or other equipment you may be adding and have your hive tool in hand. It’s not good to leave a colony open if you have to run back to the house.

This may seem obvious, but quickly scan the ground for rocks, branches, or toys. Stepping on one of these with your hands full of a box of bees can be disconcerting. Check to make sure nothing is on the hive stand where you plan to set your boxes, either, and don’t put the things you brought with you in a place where they will be in the way before you use them. Whenever possible, minimize moving things more than you need to—it saves the back and the temper.

When everything’s assembled, you’re ready to puff the tiniest puff of smoke into the front door. This will offset the guards at the front immediately, reducing any flying. Then, step back and again look at the setting, making sure nothing’s in the way and you have everything you need. This delay of a minute or so allows that little bit of smoke to waft up into the lower box just a bit and contact the dance floor area, slowing that behavior and those bees, also.

Remove the cover as carefully and as quietly as you can, but keep it close. If you have a telescoping cover, place it top-side down, next to the colony on the hive stand, about 6" to 8" (15.2 to 20.3 cm) from the colony, with the long side parallel to the bottom board. When you remove the inner cover, place it on the cover, turned about 30 degrees. Place any boxes you remove on the inner cover with the same orientation. This placement keeps bees from leaving the box from the bottom, and a bit of smoke puffed over the top will keep them inside. If there are boxes protecting your feeder, remove them and the feeder, putting them out of the way. Puff a half puff, or so, of smoke into the center hole of the inner cover, then wait a minute before you remove it to give the bees in that area time to retreat.

Pry up the inner cover with your hive tool, opening it a couple inches, and give another half puff, or so, of smoke. If bees are flying out, give a couple puffs. Slowly remove the inner cover and set it on the cover. Now, before you go any further, do this trick: with a magic marker, draw a line on the end of all the top bar lugs on one side of the box. That way, you’ll always know how to put the frames back in when you remove them. Look down between the frames. What do you see? Between the middle three or four frames will probably be lots of bees and some comb built up. Perhaps nothing has been done in this box yet, if the package is still young. If there is nothing, lift up a corner of the box and puff two or three times, then slowly remove that box and put it on the inner cover.

To begin examining a colony, lift one end of the cover a couple of inches (cm) and blow in two or three puffs of smoke.

Pry up the inner cover with your hive tool, give a half puff, and let it down for another moment, then remove it completely and give a puff, maybe two if there are a lot of bees on the top bars and between the frames. Let them go down before you begin.

Loosen the closest or next-closest frame first. Use the curved end of your hive tool for leveraging and loosening frames.

Slowly lift the frame straight up, so you don’t trap, roll, and kill bees between the comb surfaces. If you think you’re slow enough, think again. This is the hardest part of examining a colony: care and speed. Too fast and bees get killed, releasing alarm pheromone.

When reassembling your hive, be sure the frames are straight up and down so you don’t crush bees when the next frame is replaced. Use your hive tool as a lever, and the adjacent frame as the fulcrum to straighten the bottom first, and then the top.

There should be lots of bees and built-up comb on the center frames in the bottom box. If you are going to look for eggs or perform any other broodnest inspections, follow these points:

![]() Stand behind or to one side of the colony.

Stand behind or to one side of the colony.

![]() Using your hive tool, loosen the frame closest to the edge of the box or the one second closest. If there’s a difference, choose the side that has frames with no or very little comb built on them.

Using your hive tool, loosen the frame closest to the edge of the box or the one second closest. If there’s a difference, choose the side that has frames with no or very little comb built on them.

![]() Puff some smoke if bees are coming up between frames and crawling on the top bars and your hands. Watch for lots of bees lining up between the top bars of the frames, watching you. When that space is nearly full of watching bees, it’s time for more smoke.

Puff some smoke if bees are coming up between frames and crawling on the top bars and your hands. Watch for lots of bees lining up between the top bars of the frames, watching you. When that space is nearly full of watching bees, it’s time for more smoke.

![]() When both ends of the frame are free, lift one end with your fingers and the other with the corner of your hive tool.

When both ends of the frame are free, lift one end with your fingers and the other with the corner of your hive tool.

![]() Keep your hive tool flat in the palm of your hand and between your thumb and forefinger, held in place with your other fingers. This grasp leaves your thumb and forefinger of each hand to hang onto the frame when you lift it up slowly.

Keep your hive tool flat in the palm of your hand and between your thumb and forefinger, held in place with your other fingers. This grasp leaves your thumb and forefinger of each hand to hang onto the frame when you lift it up slowly.

To make sure your frames go back in facing the correct way and in the right location, simply put a line on the top of each, so they are in same order as when opened.

![]() If the frame is empty of comb, carefully set it down on end at the front door so any bees can easily find their way home.

If the frame is empty of comb, carefully set it down on end at the front door so any bees can easily find their way home.

![]() Loosen the next frame, if it’s stuck, by inserting the curved end of your hive tool between the two frames and twisting it. The leverage this position gives you is amazing, and it will loosen almost any frame. A Maxant-style tool with the hook on one end works well here, too.

Loosen the next frame, if it’s stuck, by inserting the curved end of your hive tool between the two frames and twisting it. The leverage this position gives you is amazing, and it will loosen almost any frame. A Maxant-style tool with the hook on one end works well here, too.

![]() When the frame is loose, remove it slowly, especially if there’s comb on either side. Look between frames to make sure there isn’t burr comb that will get caught and squeeze bees. Lift the frame straight up until the bottom is clear, reducing the chance of rolling bees (or the queen) between moving combs and crushing them. If there is an obstruction, come at the frame from the other side so that you move the frame that would have been gouged by the burr comb out of the way.

When the frame is loose, remove it slowly, especially if there’s comb on either side. Look between frames to make sure there isn’t burr comb that will get caught and squeeze bees. Lift the frame straight up until the bottom is clear, reducing the chance of rolling bees (or the queen) between moving combs and crushing them. If there is an obstruction, come at the frame from the other side so that you move the frame that would have been gouged by the burr comb out of the way.

When bees begin looking up at you from between frames, gently puff one or two small puffs of smoke so they go down and leave you to your tasks.

![]() Hold the frame by the lugs or shoulders between your thumb and forefinger.

Hold the frame by the lugs or shoulders between your thumb and forefinger.

![]() If there’s no comb, lean the frame against the first frame, by the front door.

If there’s no comb, lean the frame against the first frame, by the front door.

![]() If there is comb, see if eggs or brood are present. Turn so the sunlight is coming over your shoulder. Hold the frame at midchest height and away from your body. Tilt it so the light shines directly down to the bottoms of the cells. If at all possible, hold the frames over the open box or the first box you removed so that if by chance the queen is there, she won’t be lost if she falls off the frame.

If there is comb, see if eggs or brood are present. Turn so the sunlight is coming over your shoulder. Hold the frame at midchest height and away from your body. Tilt it so the light shines directly down to the bottoms of the cells. If at all possible, hold the frames over the open box or the first box you removed so that if by chance the queen is there, she won’t be lost if she falls off the frame.

![]() If you are going to look at additional frames, slide this one over to fill the empty space left by the two empty frames that were removed, keeping everybody inside and safe.

If you are going to look at additional frames, slide this one over to fill the empty space left by the two empty frames that were removed, keeping everybody inside and safe.

![]() Puff more smoke if bees are rising between frames or are starting to fly.

Puff more smoke if bees are rising between frames or are starting to fly.

Let the sun shine from behind you, directly over your shoulder, so that it shines down into the bottom of the cells.

![]() After examining the next frame as before, slide it over out of the way and examine the next frame.

After examining the next frame as before, slide it over out of the way and examine the next frame.

![]() When the examination is complete, carefully and slowly slide the frames back to their original position. Avoid squishing bees and don’t rush. When the frame is in place, look down to make sure the frame isn’t slanted. If it is, use your hive tool braced on the top of the adjacent frame to align the bottom with the top so the space for the next frame is equal top to bottom.

When the examination is complete, carefully and slowly slide the frames back to their original position. Avoid squishing bees and don’t rush. When the frame is in place, look down to make sure the frame isn’t slanted. If it is, use your hive tool braced on the top of the adjacent frame to align the bottom with the top so the space for the next frame is equal top to bottom.

![]() When everything’s back in place, quickly puff smoke on the box edges to remove those bees.

When everything’s back in place, quickly puff smoke on the box edges to remove those bees.

![]() Replace the inner cover the same way, the feeder(s), the empty box that covers it all, and cover, and call it a day. (To replace the box that covers the feeders, don’t place it directly on the bottom box, but rather offset it so you don’t squish any bees sitting on the edge, then gently twist it into place pushing those stubborn bees out of the way, minimizing any injuries and alarm pheromone. With practice, you should never crush a bee when reassembling a colony.)

Replace the inner cover the same way, the feeder(s), the empty box that covers it all, and cover, and call it a day. (To replace the box that covers the feeders, don’t place it directly on the bottom box, but rather offset it so you don’t squish any bees sitting on the edge, then gently twist it into place pushing those stubborn bees out of the way, minimizing any injuries and alarm pheromone. With practice, you should never crush a bee when reassembling a colony.)

![]() As interesting and exciting as it is to watch bees go about their business when you’re examining a colony, keep your visits to 10 minutes or less, depending on the day. Cool, cloudy days require short work. Warm, sunny days can stand a bit more time. At any rate, after a while, even the most tolerant colony begins to take a dim view of all this exposure and becomes less easy to work with.

As interesting and exciting as it is to watch bees go about their business when you’re examining a colony, keep your visits to 10 minutes or less, depending on the day. Cool, cloudy days require short work. Warm, sunny days can stand a bit more time. At any rate, after a while, even the most tolerant colony begins to take a dim view of all this exposure and becomes less easy to work with.

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT

There are a range of techniques for dealing with the problems that can befall an individual honey bee or an entire honey bee colony. The least offensive of these techniques, and safest for the bees of course, were those that prevented problems from occurring in the first place. The best way to avoid a lot of problems our bees have is to use honey bees that are resistant to, or tolerant of, the pests they encounter. There are honey bee strains that practice hygienic behaviors, some that are vigorous groomers that remove pests, others that seek out infested larvae even when capped, tear them out, and discard them. Some have shorter or longer brood times that foil the pests while others are more agile than the pests they encounter and thus can overcome them. These bees are, however, rare. They are becoming less so and you should seek them out, both for your operation and to support the producers.

The next level of dealing with honey bee pests and diseases is to use mechanical methods to keep pests from our beehives. These include keeping pests out of the hives in the first place, trapping them once they enter before their populations build up in a colony, or providing opportunities for them to leave and not return. Resistant bees, traps, and exclusion are techniques safe to use for the bees, the honey crop, and the beekeeper.

PYRAMID OF IPM TACTICS

Integrated pest management begins with the safest, least-harmful techniques of pest control, only ending up using toxic pesticides as a last resort.

The next level of defense is more intense: chemical alternatives, and within that, soft and hard chemicals.

IPM FUNDAMENTALS

To successfully manage honey bees, you need to be able to identify those pests and know what options you have to control them. You need to know what the pest population is and what it will likely be in the near and distant future if no management techniques are implemented. Also, you must know at what density will the population require treatment (the treatment threshold) so it doesn’t cause harm (the economic injury level). Also, you must know the options you have to reduce their populations within an acceptable time frame. These fundamental steps are no different from the pre-emptive measures taken for managing garden critters: fences for rabbits and groundhogs, fake owls for birds and gophers, resistant plants for some diseases, plant disposal, and so on.

MALADIES

The first season you have bees it is unlikely you will encounter a serious disease problem. Some pests may become a problem later in the season, and if you have bought used equipment, some of these diseases may show up. But mostly, new bees on new equipment have a honeymoon before the problems of the world come home. By the fall, during the coming winter and by the second spring, however, you need to be most aware of all the bad things in the world.

NOSEMA

Nosema is a protozoan-caused disease spread by Nosema ceranae spores that attack only adult bees after they have consumed the spores. Once consumed, the spores germinate inside the bee and send a long, coiled stylet through the wall of the bee’s midgut and begin consuming the hemolympth of the bees, which is, essentially, the blood of the bee. This nourishes the Nosema protozoa so that it matures and produces more spores. Some of these spores remain and continue to infest the host bees, while others are expelled in fecal material, thus spreading the disease inside the colony, and outside near the front door, on flowers, at watering sites, and anywhere infested bees go.

Symptoms are not easily observed, especially in the early stages, and it can be a difficult disease to identify. The most certain way to know if your bees have the disease is to send a sample of bees to the USDA Honey Bee Research Lab in Beltsville, Maryland. They will examine your bees and tell you a lot about them—the presence of Varroa mites, the number of Nosema spores, the presence of American foulbrood disease (AFB), and whether the disease is resistant to the commonly used antibiotic. Because of the seriousness of nosema, here’s a recommendation you probably won’t hear anywhere else: Send in a sample of bees right after you get your package. The lab will tell you the average spore count per bee, which can range anywhere from 0 to several million. The test is free but may take a couple of weeks for the results. Do it anyway.

Emergency supercedure cells: Your bees build them when they have lost their queen suddenly (such as in a case of nosema or an accident). The bees select a larva that is less than three days old and begin to produce a queen cell that hangs down from the cell the larva was in, hanging between the frames, to accommodate the larger queen larva that will eventually form in this cell. These may occur for any of several reasons, and they are always a warning sign.

When you send bee samples to the Beltsville bee lab, the scientists there will remove your bees from the bag containing bees and alcohol and grind them up using a mortar and pestle. The solids are strained out and the liquid placed under a microscope. The sample is in a grid and counting spores in a single grid provides a good estimate of how many spores per bee were in the sample. A heavily infected bee will have between 7 million and 10 million spores.

The best approach is to assume your bees have a mild infestation and to combat it the best way you can. Since the protozoa attack the midgut of the honey bee, she tends to stop eating and eventually starves to death. Before the bee dies, the protozoa consume the interior of her digestive system, mature, reproduce, and spread more spores.

The best way to combat this disease is to make certain your bees continue to eat a healthy diet. To do this, start by making available lots of honey or sugar syrup and fresh pollen or pollen supplement to a colony that seems to be listless and not eating and especially to a colony that isn’t foraging well when others are. If that in itself doesn’t inspire them, try a feeding stimulant that makes their food more attractive!

There are several feeding stimulants on the market that all contain various essential oils and herb extracts. Lemongrass oil, thymol, and other essential oils stimulate even infected honey bees to eat, and eating combats the disease. Continuous feeding at the beginning of a season (or at package installation) has been shown to reduce spore counts, and even reverse the disease. Even bees not infected will eat more and remain healthier because of this.

Beekeepers have found that the essential oil feeding stimulants have good results, and this is currently the only way to combat this disease. There are, however, new compounds on the market that are said to aid the bioenvironment of the honey bee digestive system. Initial tests seem to support the claims of these products, so I’d suggest following up on them as more bees are exposed to them. If they prove to be effective, it would certainly be a positive, and chemical-free, treatment.

Another recent discovery is that a colony infected with nosema that is handling the disease by being fed good food and essential oil additives sees a huge and rapid increase in spore production when exposed to even tiny amounts of agricultural insecticide. The pesticide seems to weaken an already stressed organism’s immune system past its ability to continue handling the disease.

One thing to keep in mind: If your queen encounters nosema, she’s a goner. The disease is especially hard on queens because it wreaks havoc on their ability to lay eggs.

CHALKBROOD

Chalkbrood, Ascosphaera apis, (usually called chalk), is a fungus that attacks the larval stage of the honey bee. It is a disease that shows up when the colony is stressed, especially with food shortages and erratic temperatures. Damp, cold conditions don’t help the bees any, and keeping a colony in a high, dry location and providing as much ventilation as possible is recommended to reduce incidence of this disease. Spring is the most common time of the year for this to show, but it can appear at any time. Recall the genetic diversity of the worker population that may keep this disease completely in check or allow it to run rampant any time of the year.

Somewhat like nosema, chalk is spread by spores from previous infections. Spores are first encountered when bees from your colony rob an infected colony, bees with spores drift into your colony, or you exchange equipment from an infected colony with one that isn’t.

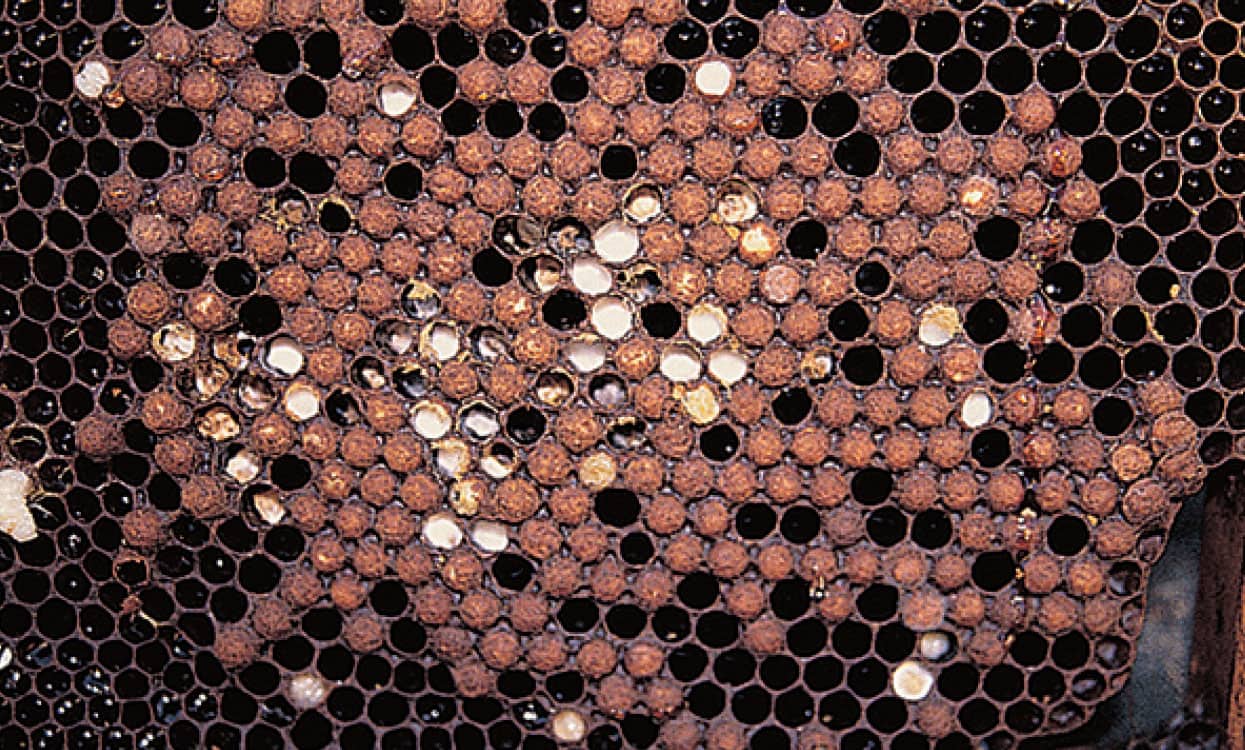

You’ll first see chalkbrood mummies on the bottom board, having been removed by house bees.

You’ll also see chalkbrood mummies in cells in the broodnest. They will be white, chalky, and hard. They may rattle when you move the frame. Some may have black spots on them, meaning the disease has matured to the point of producing spores, providing additional means of infestation.

Adult bees that have cleaned up larvae that have recently died of chalk inadvertently feed spores to other larvae. The spores are ingested, then germinate in the gut, and compete with the larva for the food. Very soon the fungus will cause the larva to starve to death. It then invades the tissue of the larva, consuming it and spreading its hyphae throughout the dead larva’s body tissue, consuming it all. Eventually, the body tissue turns hard and is chalky white. This is called a mummy. If conditions are favorable and more than one strain of the fungus is present, when mature, the fungus will mate and reproduce, casting off black spores; the dead larva now becomes white with black splotches on it. When nurse bees go to remove the chalky dead larvae, now hard and rattling around in the cell, they get some of these spores on their bodies and then share them with young larvae, completing the circle. It is a serious problem when a high percentage of the larvae in a colony die because of it.

The best defense is to have bees that are extremely hygienic who will clean out dead larvae before the fungus matures and produces spores. Good management and resistant bees are the things that work.

EUROPEAN FOULBROOD

Yet another stress disease, the bacteria Melissococcus pluton is associated with springtime stress. Much like chalk, spores are fed to young larvae by nurse bees. Spores germinate in the midgut of the larva, aggressively and rapidly compete for food, and the larva starves at a very young age, before the cell is capped. The bacteria consume the larval tissue until all that’s left is a twisted, brown rubbery mess, usually still curled at the bottom of the cell. Sometimes, they are stretched out lengthwise along the side. These “scales” are removed by nurse bees who then contact the spores.

Like chalk, spores are first encountered when bees from your colony rob an infected colony, bees with spores drift into your colony, or you exchange equipment from an infected colony.

Your first indication of an infestation is a brood pattern that appears spotty. Careful examination of an early infestation shows dead and dying larvae in the very bottom of brood cells that are not snow white! To repeat: The fastest sign of a problem with larvae is that they are no longer snow white. A darker color is always a bad thing and needs to be attended to. After the larvae die, they appear as scales—lying along the length of the cell. You can easily remove these with a toothpick to examine further, but the key is recognizing the color change and quick removal.

European foulbrood–infected larvae are first noted because they are tan to yellowish, turning dark brown and eventually to black. The larvae die before the cell is capped, which is one of the tell-tale signs used to distinguish between this and American foulbrood, another bacterial disease. Plus, the remains are easily removed by the bees, thus somewhat reducing the incidence of further infestation.

European foulbrood–infected larvae are dark brown to black, rubbery and sunken to the bottom or along the side of the cell. The telling symptom here is the color of the larvae. They should be stunningly, shiny white with no off color at all. White is right for larvae.

Consider treatment the same as for chalk. Use hygienic bees, reduce stress to a minimum, make sure adequate food is available, provide good ventilation, and make sure that the colony gets as much sun as possible. Generally, a good honey flow, warm weather, and a healthy population of hygienic nurse bees cleans up European foulbrood (EFB). You most likely won’t see this the first season you have bees from a package, but, like chalk, watch for it the next spring. Requeening is always a good idea if this becomes a persistent problem. There is an antibiotic remedy for this disease, should you choose to pursue this course of action. It is the same antibiotic used for AFB. You must have a veterinarian’s prescription to obtain it, and that vet must already know of you, and your operation. Food, resistant bees, full sun, and reduced stress are easier, safer, faster, and self-sustaining remedies to chase rather than a long-lasting drug.

AMERICAN FOULBROOD

American foulbrood (AFB) is caused by the bacteria Paenibacillus larvae. This is by far the most destructive disease (not pest) honey bees get. AFB is spread by spores that are consumed by larvae during their first couple of days in the cell. After that, they become immune to the disease.

You will probably never encounter this disease in your colonies. It is rare and well policed, but it is so very serious we need to spend some time with it, first, so that you can recognize it if it does show up, and second, so that you can efficiently deal with it so that it doesn’t spread.

Spores enter colonies in a variety of ways:

![]() Workers rob a wild colony, another apiary, or another colony in your apiary, and bring home spores inadvertently through contact or in the honey they stole.

Workers rob a wild colony, another apiary, or another colony in your apiary, and bring home spores inadvertently through contact or in the honey they stole.

![]() Equipment previously contaminated is sold and reused.

Equipment previously contaminated is sold and reused.

![]() Frames are moved from a colony with AFB to one without it.

Frames are moved from a colony with AFB to one without it.

![]() Gloves and hive tools used when working a colony with AFB are not cleaned before use in another colony.

Gloves and hive tools used when working a colony with AFB are not cleaned before use in another colony.

Spores are fed to larvae 50 or so hours old or younger—a very small window—and the infection begins. Older larvae have a built-in resistance and are not affected. Once ingested, the spores germinate and begin consuming the larvae, much like the other diseases mentioned. The larvae eventually die but only after the cell is capped. Before they die, the larvae turn a brownish/yellow color. This is a sure sign that something is wrong in a colony. Larvae should always be a stunning, nearly neon white. And they should be shiny and glistening, not dull.

Because of the seriousness of AFB, most state departments of agriculture have regulations on containment, treatments, and controls. There are a couple of antibiotics (a tylosin product is one) labeled for use when a colony is officially diagnosed with this disease (from samples taken by a bee inspector and confirmed by a recognized diagnostic lab, such as the USDA, and then prescribed by a vet). You cannot use either to prevent the disease, just as you would not take an antibiotic to prevent a disease you did not have. Resistance to antibiotics is a worldwide problem and this is one way to prevent that from occurring here, and the main reason the FDA has moved to regulate its use by prescription rather than routine prophylactic use to prevent the disease from flaring up, and to prevent exposure of a human-used antibiotic from contaminating human food. With no medication to control this disease, and since even good hygienic bees and stress reduction does not help, what’s the answer to AFB? Extreme beekeeper hygiene. Careful examination and diagnosis can locate symptoms early so that brood frames, and entire supers if necessary, can be removed and destroyed. Frames with diseased larvae can be removed and burned, but recall that the larvae don’t die until the cells are capped, so detection isn’t easy, especially when the infestation is small and early.

You can assume that in even a mildly infested colony, most of the broodnest-area bees—those that feed and clean—have AFB spores associated with them. Further, these are some of the bees that take nectar from foragers, passing spores to them also.

A spotty brood pattern is always a sign of trouble and is a first, best sign of American foulbrood disease. This is your most obvious clue that a disease is present.

One diagnostic technique for American foulbrood is what is commonly called the rope test. Shortly after the cell is capped, the larva dies and its body becomes jellylike. Poke a small twig or toothpick through the wax capping and carefully stir it around. Withdraw the probe very slowly and the sticky mass of dead larva will cling to the probe. It has the consistency of mucus. The color will be coffee brown to dark gray, and it will draw out of the cell 1/2" to 1" (1.3 to 2.5 cm) before it snaps back. Though distinctive, this isn’t the definitive test for AFB. If the rope test is positive, you should check for signs of this disease in all your colonies.

Once, bees were removed from the existing, infected equipment, shaken into brand-new equipment, and left to rebuild with new wax and no brood. But shaking bees is going to cause a lot of bees in the air, many drifting to other colonies, and similar problems with neighbors and other colonies. Regulatory agencies in the southern United States have developed a technique to rapidly contain a colony of bees when they are African and endangering people or pets. They cover the hive with commonly available, large plastic lawn litter bags. This contains all the bees in the hive, protecting nearby people, or eliminating the spread of AFB. If the weather is hot, as is common in the region, the colony quickly overheats and expires.

After the bees are dispatched, they use a burn barrel instead of a hole in the ground, which can be destructive. Frames, combs, and hive equipment are placed in the barrel with flammable material, and the equipment, and the disease, are destroyed by fire. Supers need not be destroyed, to destroy any lurking spores, crisscross and pile the supers on top of the barrel, letting the flames rise through them, scorching the insides and edges. The wood should be browned, but not blackened. When done correctly, there is no honey, no wax, and only ashes left.

VARROA MITES

For more than thirty years, Varroa mites and the problems that arise when they are present have been the most challenging health problem honey bees and beekeepers have had to deal with. And during those three-plus decades, things have gotten worse and better, relative to the damage the mites cause and how we deal with them.

The importance of handling Varroa mites in your colonies cannot be stressed enough. Controlling Varroa mites in beekeeping is as important as knowing which side of the road to stay on when learning to drive. Mostly, if you don’t control Varroa, your bees die. The upside is that detection and management are improving. Following the most recent techniques is important, and attending classes, reading recent publications and simply paying attention to your hive will go a long way in helping you manage this pest.

If you remove a larva from its cell that has a Varroa mite already in it, this is what you will see. Note the size and color of the Varroa mite. They are easy to identify. Generally, when you remove the pupa from the cell, the mite will scurry away, and they can move fast. If the infestation is heavy, there may be several adult females and many nymph stage mites present in a single cell.

How to Monitor Mite Populations

The most fundamental key in this ongoing battle is knowing where your bees stand relative to how many mites are in a hive. Knowing that number will tell you if there are so many there that you need to act, or if your avoidance techniques are paying off and you can relax. Count mites at least once a month and sometimes more often all during the season that access is possible. This may be at least twelve times, or more, a year if you have active brood all year long. This is a lot like monitoring pests in your garden, lawn or on pets. And this is important, for gardens, pets and bees. You don’t want to just treat. You want to make sure you have done everything possible to keep pest populations in check before you introduce control techniques into the equation. These may be simply fundamental integrated pest management techniques like making a divide, or a drastic, invasive technique like putting poison in a hive—trying to kill a bug on a bug. Avoid this at all costs.

A good comparison of size between a Varroa mite and an adult honey bee.

Sampling techniques and equipment are continuously being refined, becoming easier, faster, and more reliable. It pays to keep up with the technique du jour but, for now, we’ll explore what is considered by most the best there is.

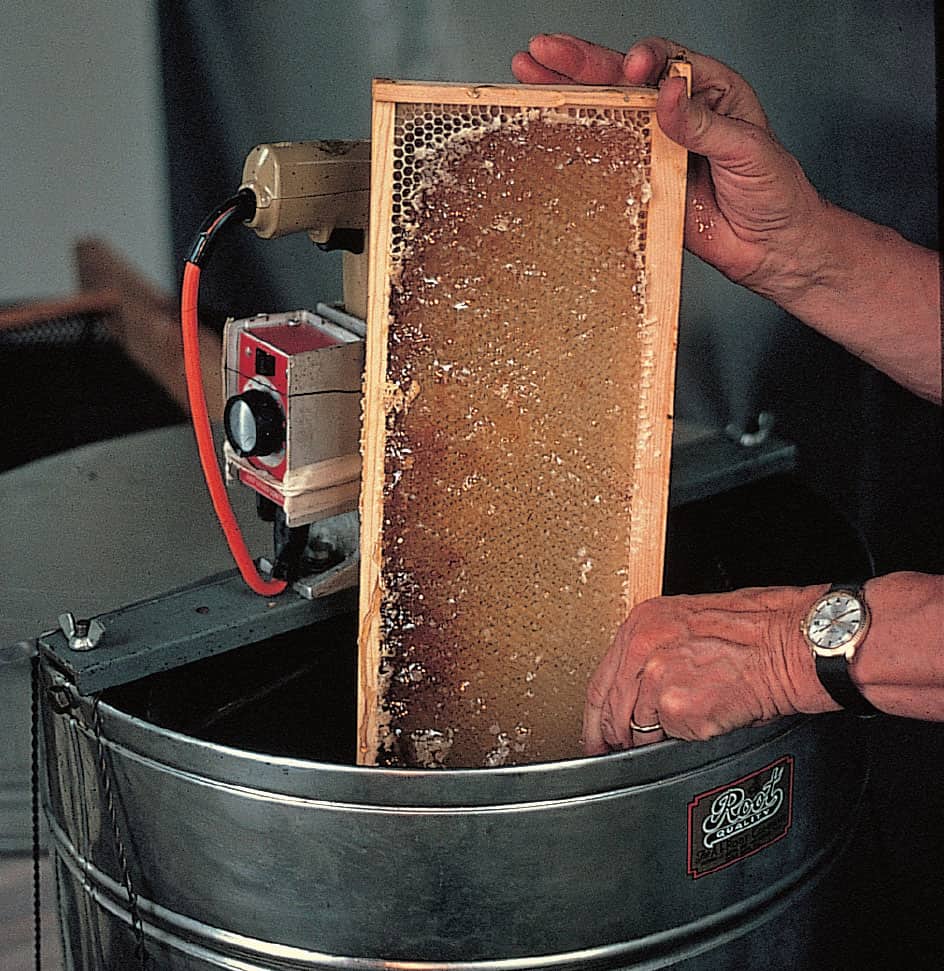

It’s called the alcohol wash. Basically, what you are going to do is capture about 300 bees, or about a half cup (118 ml). Put them in a jar with a cover of mesh small enough to allow mites and alcohol to pass but contain the bees. Then you’ll add enough alcohol (70 percent isopropyl, or even window washing fluid works) to just barely cover the bees, swirl them around in the wash for a few moments. This, unfortunately, sacrifices the bees, but it also kills any adhering mites and loosens them from the bees. Pour out the alcohol into a filter that captures the mites. Then count the mites and make a decision on your management.

Divide the number of mites captured by the number of bees sampled to obtain the infestation of your colony of phoretic mites and then follow local guidelines that offer colony size and seasonal information on how to proceed, and if you even need to do more.

How Do I Avoid Varroa Mites?

First, purchase strains of honey bees resistant to Varroa mites. Russians are very tolerant of Varroa populations. Not perfect, but not bad. There are others available, and more are becoming available routinely. Ask members of your local club and check journals for the latest in where to get bees resistant to varroa. Resistance is the answer to this pest, not poison.

Some commonsense management tricks will help your colony deal with mites all the time.

Mid-Summer Splits

This is, without doubt, the finest example of working with the bees I can imagine. With a first season package it might not work because of a slower-than-hoped-for population increase, or a poorly preforming queen eventually being replaced. But for even an average package, and especially an above average colony, it works like this.

By dividing the population of bees and brood, each resulting colony ends up with half of any mites that were present in the original. Then, one of the split colonies has the original queen, and one is queenless. For the half with the original queen, you can cage the queen for three weeks, allowing every existing brood to mature and emerge. This exposes absolutely every mite in the colony, making them all vulnerable to grooming, or an organic acid mite treatment. After three weeks and a treatment, you can either release the queen from her cage or install a new, young, genetically stronger queen of your choosing. The queenless half works about the same when you install a new queen.

What you end up with are two strong colonies going into winter with no mites and vigorous laying queens giving the colony a good population of extremely healthy, nonviral infected, and well-fed winter bees.

Treating Varroa Mites

For an active, healthy colony with even an average queen, spring and summer buildup will appear normal because the rate of brood production by the bees outpaces the rate of reproduction by the mites for much of the summer. However, as summer winds down, the queen begins to slow egg laying and both the brood and adult populations begin to decline in preparation for winter. Mite reproduction, however, remains steady, with some changes. For much of the summer, the mites have been infecting drone brood far more than worker brood. When drone populations decline in the fall, the mites turn to the worker brood and infest worker cells. It takes only a short time for much of the worker brood to become infested.

Basically, using poison is a bad idea. A more positive approach is to use products that are not poison, but rather physically damaging to the mites. There are two essential oil products available. One is Apilife Var, which is thymol, menthol, and eucalyptus oils soaked into a foam block. Break the block into four pieces and place one on each corner of the cluster, not the corner of the box, in the top box. These products need to be applied every seven to ten days. Another essential oil product is ApiGuard, which is primarily thymol oil and inert ingredients. It is a gel-like compound contained in a very thin aluminum foil container, or in bulk as a peanut butter–like compound smeared on top bars. For the single application, remove the cover, place on the top bars of the top super, and let it evaporate while the bees remove the gel. Don’t use below 60°F (16°C) or it won’t evaporate or above 105°F (41°C) or it will evaporate too fast, driving bees out of the hive and harming brood. These are not poison.

Another non-poison product is called Mite Away Quick Strip, a gel-based formic acid product that slowly evaporates. It is effective, leaves no residue, but can harm queens and brood if applied when too warm, and is mostly ineffective if applied below 50°F (10°C). It attacks free roaming mites and those in cells. Plus, it is downright dangerous to those who apply it. Gloves and a mask are necessary. But it is by far the most effective product there is relative to residues—there are none—and efficacy.

The newest treatment on the market requires protective gear and is very effective. It is oxalic acid. It can be used as a drip in sugar solution and as a vaporized gas. Use of this compound is evolving with even more effective and safer application methods, and its potential is improving. It is the perfect compound for a late summer/fall Varroa bomb treatment.

As we said earlier, it’s always a trade-off: efficacy versus beekeeper safety versus ease of use versus honey bee safety. If you choose to use a Varroa mite chemical treatment, be certain to read labels, follow instructions, and be safe—for you and your bees.

WAX MOTH

Wax moths, Galleria mellonella (also known as greater wax moth), can be a real nuisance, but they can be taken care of pretty easily.

Sometime during your bees’ first summer, a mated female wax moth will find your colony. She’ll get inside by sneaking past the guard bees, usually at night. Once inside, she will lay eggs somewhere in one of the boxes with brood. The eggs hatch, and the moth caterpillars begin to feed on beeswax, pollen, honey, and even larvae and pupae, that is, unless house bees catch and remove them. If the colony is strong and healthy, the internal police force is very protective against these invaders. But small colonies, or those being stressed by other troubles, aren’t as diligent and wax moth larvae can make some inroads.

If they get a foothold, the moth larvae tunnel through your brood comb, leaving webbing and frass (excrement) everywhere in their paths. Unimpeded, wax moth larvae can, with favorable temperatures, completely consume the comb in a super in ten days to two weeks. They eventually pupate, spinning tough cocoons fastened to the sides of supers, top bars, or the inner cover. They literally chew a groove into the wood so they fit. The cocoons are so tough that bees can’t remove them. Adult moths emerge, leave the colony, mate outside, and then the females find more colonies to infest. They’ll do the same to supers you store in the basement or garage, unless you take some precautions.

Wax moth adults are around pretty much all year in tropical and semitropical areas, and most of the year where there are mild winters. In cold climates, wax moths are a problem only from midsummer until hard frost—outside, that is. Inside the hive is a different story.

Adult wax moths are about the size of an adult worker honey bee.

Wax moth larvae, like the one shown here, do great damage in a beehive. The larva is an off-white, soft-bodied caterpillar. This one is about half grown.

As the larvae eat their way through the comb, they leave behind webbing, which hinders the bees from catching and removing them and from being able to use the comb or even clean it.

Cocoons of wax moth pupae are very tough and bees usually can’t remove them.

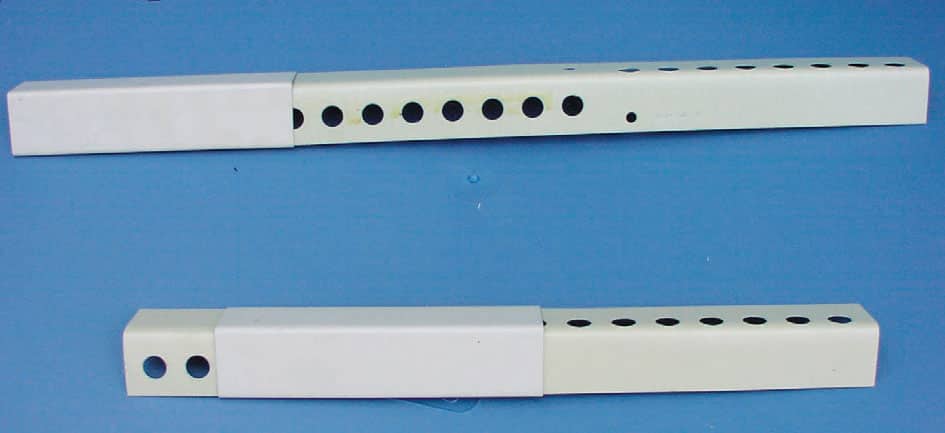

Here is an easy-to-build storage rack for supers when they are not on a colony. This arrangement allows light and fresh air into the supers, discouraging wax moths from infesting combs. It also protects them from the elements. It is made of boards, cinder blocks, and PVC pipe, and could be made longer, taller, or wider, as needed. The supers are covered with inexpensive corrugated fiberglass panels weighted with additional pipe, blocks, or other heavy material.

Storing unused supers so light and air can penetrate between frames makes them unattractive to wax moths and doesn’t require a frame or shelf.

SMALL HIVE BEETLE

Small hive beetles and our honey bees have had a decade or so to become acquainted since the beetles accidentally arrived in the southern United States from South Africa. Ironically, small hive beetles are not an issue in South Africa because the aggressive African honey bees manage to keep them in check. However, the more docile and inexperienced European honey bees common in South, Central, and North America were less prepared for their onslaught. Hives infested with these beetles can be moved from the warmer parts of the United States to the more northern areas, where the colder winters and the less sandy soil types generally keep populations in check. There are occasional outbreaks when beekeepers aren’t paying attention or when infested colonies move into an area to take advantage of a honey crop or for commercial pollination. When the colonies crash due to beetles, Varroa, or starvation, the beetles will leave and find a new home, but only after they have consumed everything worth eating in the now-deserted hive.

Here is an adult hive beetle on the edge of the inner cover and another on top of the inner cover—both scurrying for cover when the outer cover was removed. You almost never see a beetle sitting still. When you open a colony, they run from the light. They are about one-third the size of an adult honey bee.

Small hive beetle larvae resemble wax moth larvae, but they tunnel without webbing and are very destructive. Pick one up and draw it between your fingertips. The cuticle is hard and unyielding, and the legs are stiff and bristle-like. Wax moth larvae are soft and pliable and easily crushed.

As the larvae tunnel through the comb, they defecate, which causes the honey to ferment and become runny and is called slime. In extreme cases, the slime will run right out the front door. The bees will abandon the hive long before it gets to that point.

A disposable small hive beetle trap. Fill the reservoir half full of vegetable oil, then place between two frames near the edge of the top box. Beetles will hide in the opening, only to fall into the oil.

Beetles can fly long distances and are attracted to colonies that have been disturbed and have released some alarm pheromone, scientists tell us. Queen producers (in the southern region of the United States) who use small mating nucs have problems because there aren’t enough bees to defend the colony, and very often colonies that go queenless decline and are destroyed by the beetles.

It’s unlikely you will see beetles in your package colony (though you may see them in your package before you install it. If so, try and remove them before installation)—but if you do see them early, you will likely see them in greater numbers as the summer moves along. You will notice them especially on the top of the inner cover when you remove the cover or on solid bottom boards.

Destruction can be extensive. Mated females lay clusters of tiny eggs in locations the bees don’t have access to. The eggs hatch and hundreds, and even thousands, of aggressive larvae tunnel through brood comb, honeycomb, any comb seeking pollen and especially larvae and pupae to eat. As they tunnel, they excrete a liquid mess that causes any honey it contacts to ferment and bubble and turn into what beekeepers call beetle slime.