CHAPTER 5

Fundamental Principles of Financial Analysis

Good Analysis = Due Diligence?

Until the headlines at the turn of this century surrounding Enron, WorldCom, Health South, Tyco, and Waste Management, followed by Adelphia Communications, AOL Time Warner, Parmalat, and many others, it is unclear what the general public knew about analysis of financial information. Specifically, what did the non-expert know about analysis and deduction when it came to financial results and information, and how to interpret it?

Now that we have a basic understanding of financial fraud, how it occurs, who commits it, and some of the underlying principles of accounting and entities involved, we need to consider how a nonexpert can undertake financial analysis and understand what it all means.

Financial analysis can be conducted as part of due diligence before a transaction occurs, and as part of an investigation after a fraud has occurred or is believed to have occurred. Typically, the sheer volume of transactions within a business will prohibit the ability to examine each and every piece of paper and underlying transaction. Financial analysis therefore may be needed to first identify and then focus on the problem areas, to perform due diligence before a transaction is consummated, or to determine specifically what areas to investigate in a fraud situation. It is the latter that is the focus of this book and therefore the focus of this chapter.

If a party suffers a loss, largely due to the lack of financial due diligence or at least some level of financial analysis not being performed, the pain of a bad bargain will live on long after the excitement of the particular transaction has faded to a mere memory. Even well-trained, highly educated, sophisticated, and experienced businesspeople get swept up at times into deals too good to be true, or because a deal was presented by well-respected colleagues and friends, only to enter into a transaction not only knowing too little about the parties, but also not understanding the metrics of the underlying data. A case in point is the Bernie Madoff scheme, where hundreds of individual and organizational victims simply relied upon the recommendations of highly regarded figures, friends, and colleagues, without performing any independent due diligence on the soundness and reliability of Madoff's strategies and investments.

In the face of the large-scale frauds that have occurred over the past few years and continue to be revealed today, it is clear few people truly understand what it all means, and even fewer understand the most basic of financial analyses. The concept of financial analysis, or due diligence, call it what you like, is an understanding of what is being presented before making a commitment. That commitment could be providing financing to a sole proprietor, allowing the person to take the business to the next level, or it could be an individual buying into a partnership. It could be deciding to invest in a major corporation, or deciding to acquire the assets and operations of a competitor. It could be the joining of two businesses to create a partnership, or it could be a bank entering into an agreement to provide significant financing for the construction of a new facility. It could even be an investigative journalist trying to get a better understanding of a company's results for a particular story.

The size of the business and the type of entity involved may dictate exactly which procedures are followed. However, before you undertake any financial analysis, you must take the time to understand the underlying business you are analyzing. Gaining that understanding will not only establish the context for your financial analysis, but also create some expectations of what you should find through your analysis. If possible, on-site visits and tours can provide the best means to understand a business. Other means may include Internet searches, trade publications, and Google Earth satellite “visits” to company locations.

Case Study: Insurance Claim Fraud

The insured had one known retail location, and the primary product sold was jewelry. According to the insurance claim filed, the insured purportedly suffered a loss through a burglary during a thunderstorm. The thieves allegedly cut the alarm wires, and after the police cleared the area, broke down the back door to the business. Once inside, the perpetrator(s) broke through the hollow door to the closet where the jewelry was stored each evening. Close to all of the store's inventory was stolen, valued at around $200,000.

The challenges the investigators faced were that the store's owners did not speak English, and they claimed they had no means to track and record store sales. Therefore, the only records the owners could provide investigators were the annual tax returns for the business.

Before looking at any financial records or tax returns, I drove to the store's location to go shopping. As the owners had never met me, I was confident they would have no idea I had been hired to analyze the financial information for their store. As I entered the store I noticed the cash register sitting on the counter at the close end of the jewelry displays. There was register tape extending out from the front of the register, hanging over the back of the register heading toward the floor. This told me the register was likely operational and was also their means for tracking store sales.

I purposely looked through the glass displays as I walked toward the rear of the store. I was looking for any item they didn't carry and discovered they had no charms on display. After a minute or so the woman working behind the counter came over. A quick glance revealed she matched the description of one of the owners of the store. She asked me, in English, if I was looking for something in particular. When I told her I was looking to buy a charm for my wife, she told me they didn't carry charms. I asked her where I could buy one, and she provided me directions, in English, to a nearby mall. I purchased a cheap pair of earrings and watched as she rang my sale through her register.

From the parking lot I called the insurance investigator and told him that she spoke English, and quite well, and that they used a cash register to record and track their sales. These discoveries led to the owners having to provide additional records as well as explanations for why they didn't retain the cash register records. The existence of jewelry in the store at the time of the “burglary,” and the amount purportedly taken, could never be determined due to their lack of records. In the end the insurance company settled the claim for a fraction of the claimed loss.

My on-site visit and mystery shopping easily allowed me to overcome the two major obstacles in the case, as well as established for me expectations of the type and volume of sales I should expect to see in the store's financial records. There is no way these could have been accomplished without my on-site visit.

Any type of financial analysis you perform will obviously involve numbers. However, depending on the reason for the analysis, it may involve more than just looking at the numbers. It may require a deeper investigation that, among other things, looks at the company, the markets and industries in which it operates, how the asset values are calculated, the potential for undisclosed or undervalued liabilities, whether or not strategic planning has been completed, the company's budgets, the condition and strength of the internal controls, the sophistication of the board (if one exists), and other aspects of the organization. Unfortunately, experience has shown that even the most rudimentary analysis is conducted after the fact—the famous “historic perspective” that traditional financial statements offer. Anyone who has been the victim of fraud, or has investigated fraud, likely will tell you that there are always “red flags” identifying the potential for fraud. The common issue is why the red flags were not recognized.

Why Perform Financial Analysis?

The way business is conducted and how it is recorded has changed since the days of Luca Pacioli, the father of accounting, and changed again with the advent of computers. And it certainly has changed in response to the corporate shenanigans of the past 10 years. But has the actual business really changed, or has the underlying way in which results are captured changed? At the root of all business is one thing—money—specifically, the need to make it, keep it, and grow it, and all are driven by the human element. This may be no different today than it was 500 years ago; perhaps just the pressures have changed.

Although the recent scandals have mostly surrounded publicly traded companies, with the perception that they can inflict the greatest impact on outsiders, let us not forget the privately held companies, the partnerships, and indeed the sole proprietorships, in which someone on the outside may soon have an inside interest. The breakdown of confidence in financial statements and their underlying data should apply across the board, not just to public companies. Every organization, including closely held businesses, nonprofit organizations, partnerships, trusts, and governmental units, should all be held accountable.

What and Whom Can You Trust?

“Trust” is an interesting word in the world of forensic accounting and fraud. In the words of the late Ronald Reagan, “Trust but verify.” Trust has caused millions of individuals and businesses to fall victim to financial crimes. One recent case should remind everyone of what happens when too much trust is placed on relationships rather than on independent, objective, and accurate financial information. Investors with Bernie Madoff and his organizations lost an estimated $60 billion. Coined the largest Ponzi scheme (stealing funds of later investors to pay returns to earlier investors), investors lost their life savings, retirement funds, and trust funds, mainly because they relied solely on the financial information and reports that were provided by Madoff, all while Madoff was stealing their funds for personal use.

Historically, analysts believed that audited financial statements contained all the information needed for their financial analysis. This misconception was common not only within companies looking at acquisition targets, but also within banks, bonding companies, vendors, customers, and any other type of business wishing to establish a relationship with another company. The exposed misrepresentations on the financial statements of Enron, WorldCom, AIG, Lehman Brothers, and others should sufficiently demonstrate that making an investment decision based solely on the analysis of an organization's financial statements can be dangerous if not disastrous.

Financial statement fraud has been occurring as long as financial statements have been prepared and issued, but the financial scandals show that not even the largest and most important companies in the economy can remain untainted. In 1998, then–SEC chairman Arthur Levitt warned in a speech called “The ‘Numbers Game’ ” that aggressive accountants were exploiting the flexibility of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) to create misleading earnings reports: “As a result, I fear that we are witnessing erosion in the quality of earnings, and therefore, the quality of financial reporting. Managing may be giving way to manipulation; integrity may be losing out to illusion.”1

Due to the downturn in the economy starting in 2008, and the continued economic climate of today, Levitt's comments are as relevant today as they were when he made them in 1998.

Other Factors to Consider

In the post-Enron era, mere analysis of audited financial statements may not be enough, and other key performance indicators may have to be considered. Margin and other ratio analyses will, of course, always be important, but a thorough examination may have to extend to customers, vendors, underlying costs, product lines, and market shares, among many other factors. Additional time should be spent talking to vendors and customers to more fully analyze the industry in which the company operates.

When assessing competitor and market risk, prospective acquirers frequently access and rely upon information obtained from analysts and self-proclaimed industry “experts.” Recent revelations have shown the significant risk of bias in these sources. In addition, in the eagerness to complete a transaction, human nature inadvertently causes greater weight to be placed on positive information and less on negative. Early warnings of potential problems are frequently ignored.

The analytical process should “drill down” beyond the amounts and transactions, looking at the underlying controls and procedures, to find out who authorizes and approves individual transactions, and to ask why. Skepticism should guide the examination of all questionable transactions. In the case of a prospective acquisition, more emphasis should be placed on analyzing whether there is a real need to acquire the target and what its long-term impact on the existing strategy could be. Many ill-advised boards of directors have authorized the acquisition of companies in businesses dissimilar to their own management but argued to be capable of providing what used to be called “synergies.” The results almost always have been disastrous.

Lenders, suitors, or any other agents surveying a company need to be alert to factors and issues they may not have considered previously. The old emphasis on net income should now shift to cash flow. It does not matter how a company records transactions once the money is spent; it is the cash flow that should be more closely investigated.

Two areas that should receive increased attention are the composition of the company's board and the company's governance practices. A board dominated by a multi-titled, charismatic, and/or domineering chairman, president, or CEO should raise a red flag. How many independent directors are there? Are they truly independent? Are they financially literate? Do they have experience in the company's business sector? How much time and energy are all directors devoting to fulfilling their duties? How effective is the audit committee? Is senior management's compensation excessive? Finding these answers can be a challenge because they are not often transparent. If effective corporate governance is not in place—and there is no control or oversight of senior management—then “caveat emptor” (let the buyer beware).

Financial Analysis for the Non-Expert

It is important to understand that financial analysis will not prove most effective if the only data analyzed are as of a single point in time. Financial information should include current and past performance, results, and balances, as well as projected and/or forecasted financial information, creating a picture of what the entity might do in the future.

Financial analysis includes three main measures: trending, horizontal and vertical analysis, and ratio analysis. Whether performed as part of a potential transaction or in support of a fraud investigation, these tools, used in combination, will provide much insight beyond the mere analysis of the most recent financial statements. Trending involves using the entity's financial information for more than one period, such as years, quarters, and months, and comparing the results and balances within key elements between periods. Monthly trending is an extremely useful tool in the detection of financial statement fraud, as it commonly identifies changes in the trends just before and after periods that are reported. This likely could identify a company's manipulation of its financial statements to achieve certain goals or levels, and, once reporting has been completed, the company's reversal of the fictitious activity to “right” the books until the next reporting period. Without performing month-to-month trending, this likely would never be detected.

Horizontal and vertical analysis utilizes the financial information provided and calculates individual elements or line items as a percentage of the totals. Horizontal analysis compares the amounts and balances between different periods, similar to trending, and vertical analysis compares the major financial items for the same period. For example, cost of sales, gross margin, operating costs, administrative costs, and interest expense can all be calculated as a percentage of gross sales on the income statement. On the balance sheet, cash, accounts receivable, prepaid expenses, and other current assets can all be reported as a percentage of total current assets, and total current assets also can be shown as a percentage of the overall total assets. Once the percentages are calculated for a given period, the same relationships and percentages can be performed for other periods, as well as within the industry and/or within competitors’ results and balances, which may provide much insight into the company being analyzed.

The Ratios

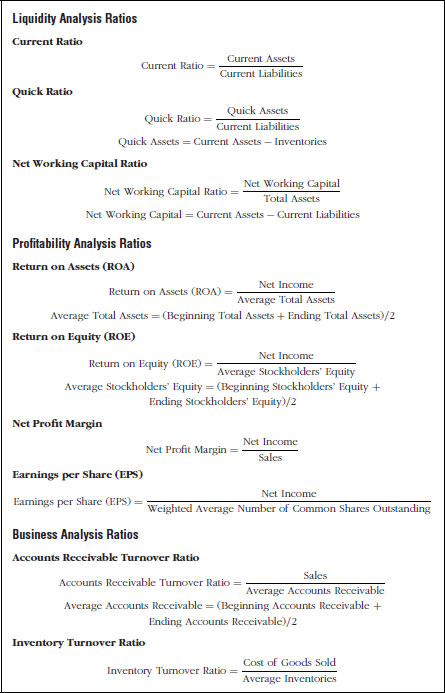

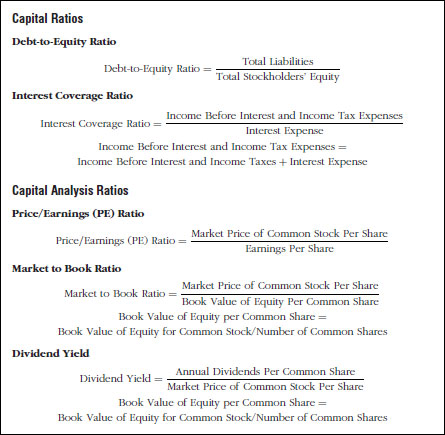

Financial ratios illustrate and analyze relationships within the financial statement elements. As Exhibit 5.1 shows, in gauging performance, certain financial ratios can be applied to an entity's financial statements. In this section, we discuss some of the more “popular” or well-known financial ratios.

- Current Ratio: The current ratio is the standard measure of an entity's financial health, regardless of size and type. The analyst will know whether a business can meet its current obligations by determining whether it has sufficient assets to cover its liabilities. The “standard” current ratio for a healthy business is recognized as around 2, meaning it has twice as many assets as liabilities.

The formula is expressed as: current assets divided by current liabilities. - Quick Ratio. Similar to the current ratio, the quick ratio (also known as the “acid test”) measures a business's liquidity. However, many analysts prefer it to the current ratio because it excludes inventories when counting assets and therefore applies an entity's assets in relation to its liabilities. The higher the ratio, the higher the level of liquidity, and hence it is a better indicator of an entity's financial health. The accepted optimal quick ratio is 1 or higher.

The formula is expressed as: current assets less inventory divided by current liabilities. - Inventory Turnover Ratio. This ratio measures how often inventory turns over during the course of the year (or depending on the formula, another time period). In financial analysis, inventory is deemed to be the least liquid form of an asset. Typically, a high turnover ratio is positive; however, an unusually high ratio compared with the market for that product could mean loss of sales, with an inability to meet demand.

The formula is expressed as: cost of goods sold divided by the average value of inventory (beginning inventory plus ending inventory, divided by two). - Accounts Receivable Turnover Ratio. This ratio provides an indicator as to how quickly (or otherwise) an entity's customers/clients are paying their bills. The greater the number of times receivables turn over during the year, the less the time between sales and cash collection and hence, better cash flow.

The formula is expressed as: net sales divided by accounts receivable. - Accounts Payable Turnover Ratio. Converse to the accounts receivable turnover ratio, the accounts payable turnover ratio provides an indicator of how quickly an entity pays its trade debts. The ratio shows how often accounts payable turn over during the year. A high ratio means a relatively short time between purchases and payment, which may not always be the best for a company (the entity would want to make sure it is taking advantage of all discounts, while not at the same time paying for goods before their time). Conversely, a low ratio may be a sign that the company has cash flow problems. However, this ratio, like all others, should be considered in conjunction with the other ratios.

The formula is expressed as: cost of sales divided by trade accounts payable. - Debt-to-Equity Ratio. This ratio provides an indicator as to how much the company is in debt (also known as “leveraged”) by comparing debt with assets. A high debt-to-equity ratio could indicate that the company may be overleveraged and may be seeking ways to reduce debt. Aside from the other ratios we have noted, the amount of assets/equity and debt are two of the more significant items in financial statements; they are key evaluators of risk.

The formula is expressed as: total liabilities divided by total assets. - Gross Margin Ratio. The gross margin (or gross profit) ratio indicates how well or efficiently a proprietor, group of partners, or managers of a company have run that business. Have the managers bought and sold in the most efficient manner? Have they taken advantage of the market? A high gross margin indicates a profit on sales, together with cost containment in making those sales. However, a high margin, but with falling sales, could be indicative of overpricing or a shrinking market.

The formula is expressed as: gross profit or gross margin (sales minus cost of sales) divided by total sales. - Return on Sales Ratio. This ratio considers after-tax profit as a percentage of sales. It is used as a measure to determine whether an entity is getting a sufficient return on its revenues or sales. Although an entity may make what looks to be a satisfactory gross profit, it still may not be enough to cover overhead expenses. This ratio can provide an indicator of this fact and help determine how an entity can adjust prices to make a gross profit sufficient to cover expenses and earn an adequate net profit.

The formula is expressed as: net profit divided by sales.

Concluding Comments on Ratio Analysis

Many other ratios exist in the course of financial analysis, but these are deemed to be some of the most commonly used and understood. It must be remembered that ratios need to be considered in their entirety; unlike in the past, even ratio analysis alone is not to be considered the most useful information. So what if a company made a 25 percent gross profit? So what if its current ratio is 2:1? Given the right circumstances and together with other due diligence, an analyst can obtain a good picture of an entity's performance and situation. The ratio analysis cannot be considered in a vacuum; rather, it is important to consider the entity, the type of entity, the industry, the market, the competition, and the management, and then consider the calculated ratios. Ratios need to be compared with prior periods, with ratios of other businesses in the same industry, and with ratios of the industry itself, if known and available.

Data Mining as an Analysis Tool

Much literature has surfaced over the past few years emphasizing the importance of data mining, both as part of due diligence procedures as well as part of a fraud investigation, whether proactive or reactive. But what exactly is data mining (also referred to as electronic data analysis), and how does it work?

While not the focus of this book for the non-expert, data mining has become an increasingly important tool for the investigator. Data mining is defined in a number of ways:

- “The process of analyzing data to identify patterns or relationships”2

- “The analysis of data for relationships that have not previously been discovered”3

- “Analyzing data to discover patterns and relationships that are important to decision making”4

In A Guide to Forensic Accounting Investigation, it is noted that consideration of data mining should be made at the outset of an investigation, specifically to determine:

- What relevant data might be available.

- What skills are available within the team.

- How will the data analysis fit in with the wider investigation.5

Data mining is simply obtaining access to an organization's electronic files containing the details of individual customers, vendors, employees, and transactions, to enable the financial analyst to perform various electronic procedures over the information maintained within those files. Access may be gained through the target's computer systems, or the files could be copied onto portable means to be analyzed outside of the entity's systems. The key is that there are two inherent limitations to data mining. The first is that analysis will be limited by the quality and quantity of information within the files provided. Simply stated, you can analyze or mine only what the company provides you in the files. For example, if the electronic files provided for an entity's accounts receivable transactions fail to include the terms of each sale for each customer within the file, the person conducting the mining will be prevented from determining whether each sale was completed in compliance with the terms established for each customer. While the sales transactions exist within the files, the terms do not.

The second limitation is that the analyses are limited by the examiner's experience and level of creativity. Data mining can be conducted at the transactional level or can be done at the much deeper field level. If, for example, a financial analyst or forensic accountant was attempting to determine whether any vendors were established using employee addresses, thus identifying the potential for fictitious vendors, the files would need to contain both the vendor addresses and the employee addresses. Next, a query could be executed, focused on the address fields within both files, looking for any potential matches.

What is most interesting about the above-noted definitions is the progression in their pattern—from identifying patterns or relationships, to identifying those that have not been discovered previously, to those that are important for decision-making. Those mindsets are important when analyzing data from a fraud investigation perspective.

Being able to examine and manipulate large volumes of electronic data is an essential ingredient of an effective fraud investigation. The ability to analyze statements and produce the ratios we discussed earlier is one thing; the ability to drill down into the underlying financial data and look at the various relationships is another.

In the second part of this book we discuss the various techniques used for interviewing witnesses, collecting evidence, and maintaining documents. These skills are essential to performing an effective investigation, as are the skills needed for effective data mining. As with all other tools, without knowing how to use the tools and actually using them on a regular basis, the end result will be disappointing.

Just as an investigation consists of the various puzzle pieces put together to form the whole picture, so does the usefulness of data mining fit with the rest of the investigation. These techniques do not negate the need for using one's experience in the area of investigation and analysis; neither do they allow an “armchair only” approach to an investigation.

To the Future

Until recent years, there was an accepted profile of companies susceptible to financial statement fraud. The typical “fraud risk” company had revenues of less than $50 million; was a technology, healthcare, or financial services company suffering losses or reaching only breakeven profitability; and had an overbearing CEO or CFO, a complacent board of directors, and a poorly qualified audit committee meeting as infrequently as only once a year. The discovery of accounting improprieties at a number of large companies shows that even Fortune 500 companies are not immune to poor governance.

The fear that we are moving into an age of untrustworthy and arrogant management bent on looting their companies may be exaggerated, or perhaps not. The aftermath of the great stock market excesses of the 1920s, the “Go-Go” market of the 1960s, and the collapse of 1987 also brought overvaluations and insider trading scandals to light that were shocking in their size and audacity, but none of them proved to be harbingers of greater corruption to follow. The companies most in need of a due diligence investigation will continue to be those with revenues of less than $50 million. However, all companies must be scrutinized with a healthy level of professional skepticism at all times.

Two cases emphasize the point of diligence and the use of data mining. The first involved a former senior government official and a lawyer, both sent to prison for their part in an $18.1 million contract procurement fraud at a Navy base in Pennsylvania. As noted in the newspaper story, Department of Defense auditors unraveled the scheme when they used data mining software and found $11 million of payments using government credit cards.

In another case, reported by Reuters, investigators used data mining programs in the fight against insurance fraud. Specifically, they used “linkage” software to find a common thread between multiple, seemingly unrelated claims.6 For example, this technique helped solve the case of a woman who claimed she found a finger in her chili at a Wendy's restaurant. The investigators found a woman with a history of filing similar claims for foreign objects in her food. By spending the time performing detailed background procedures into her past, they were able to show her pattern.

As we noted in one of our definitions of data mining, it is about the analysis of data for relationships that have not been discovered previously. As the recent news stories show, these techniques also are being used for proactive fraud detection, as well as after-the-fact investigation.

The lesson to be learned from recent corporate fraud is that companies have to be more proactive and cannot assume that the financial analysis used in the past will suffice in the future. While the acquisition of personnel and the tools necessary will involve the types of proactive expenditures many businesses previously shied away from, the lessons learned in recent years, and many discussed in this book, should drive home the point of the age-old idiom “penny-wise, pound-foolish.”7

Conclusion

Given an unlimited engagement budget, no time constraints, access to adequate staffing to provide capacity, and unfettered access to all pertinent information, nearly anything can be analyzed right down to each and every transaction to determine both the completeness and accuracy of the financial information being analyzed. Under these conditions, which likely exist only in theory, one could get to the bottom of almost any financial issue.

The problem we face is that we live in reality, where one or more of these conditions are not present within most engagements. Often, time and cost are both constraints, and gaining access to the pertinent financial information will be a barrier, either by design or by happenstance. Regardless of the efforts of the targeted individual or entity to create obstacles preventing a complete financial analysis from being performed, one should not be dissuaded from seeking the information not produced, while performing due diligence on whatever limited information is provided.

Tools and software exist today that allow a user to electronically access and analyze a targeted individual's or entity's financial information, and I strongly recommend anyone responsible for performing due diligence acquire and learn such systems. Two such systems commonly used are IDEA and ACL. If for no other reason, once access can be gained, independent, objective, and unbiased reports often can be generated via access to the information without the potential for influence or manipulation by the target.

In the next chapter we will discuss the importance of the roles accountants and the accounting profession play within the battle on fraud.

Suggested Readings

Golden, T. W., S. L. Skalak, and M. M. Clayton. A Guide to Forensic Accounting Investigation, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Levitt, A. “The ‘Numbers Game.’” Speech presented to the New York University Center for Law and Business, September 28, 1998.

Silverstone, H. “International Business: What You Don't Know Can Hurt You.” GPCC News, the Newsletter of the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, October 2002.

Silverstone, H. and P. McFarlane. “Quantitative Due Diligence: The Check Before the Check.” The M&A Lawyer 6, no. 6 (November–December 2002). Used with permission of Glasser Legal Works, 150 Clove Road, Little Falls, NJ 07424, (800) 308-1700, www.glasserlegalworks.com.

Notes

1. A. Levitt, “The ‘Numbers Game,’ ” Speech presented to the New York University Center for Law and Business, September 28, 1998, www.sec.gov/news/speech/speecharchive/1998/spch220.txt.

2. https://iomega-eu-en.custhelp.com/cgi-bin/iomega_eu_en.cfg/php/enduser/std_adp.php?p_faqid=1725.

3. www.creotec.com/index.php?page=e-business_terms.

4. www.jqjacobs.net/edu/cis105/concepts/CIS105_concepts_13.html.

5. T. W. Golden, S. L. Skalak, and M. M. Clayton, A Guide to Forensic Accounting Investigation (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006), Chapter 20.

6. http://today.reuters.com/business/newsArticle.aspx?type=ousiv&storyID=2006-03-31T194159Z_01_N31262096_RTRIDST_0_BUSINESSPRO-FINANCIAL-INSURANCEFRAUD-DC.XML.