CHAPTER 11

Proving Cases through Documentary Evidence

Introduction

We prove all cases through evidence. In general, we divide evidence into two categories—direct and circumstantial. In addition to these two categories of evidence, we classify evidence according to its nature. For example, we classify actual witness testimony on the stand in open court as testimonial evidence. The statements that you obtained during your investigation are documentary evidence, as are canceled checks, bank statements, and photographs of suspect transactions. Additionally, since hundreds of canceled checks are often difficult to comprehend as they sit in piles, attorneys prepare charts and schedules to assist jurors in understanding the big picture. We call these schedules and charts demonstrative evidence. Finally, we refer to physical objects, like guns, knives, and fingerprints, as real evidence. It is through these different classes of evidence that attorneys prove that something did or did not occur.

The difference between financial crimes and nonfinancial crimes is the composition of the evidence. Prosecutors often use real evidence such as fingerprints and tool-mark comparisons to prove crimes such as murder and burglary. Sometimes, documentary evidence like pawn receipts and photographs become important in these cases, but generally they are non-document-based cases. Conversely, financial crimes are very document heavy.

Because of this difference, investigators often must confront huge volumes of evidence. In the typical murder investigation, more than 500 pieces of evidence would be considered exceptionally high. Conversely, in major financial crimes, 500 individual pieces of evidence would be much more common. For example, the number of canceled checks belonging to a single account for a single year could easily exceed 500.

As we proceed through this chapter, we will prepare you to deal with this unique aspect of financial crime investigation. As we begin, we will focus on the basics of document collection. From consensual searches, to subpoenas, to search warrants, you will be exposed the various methods of securing documentary evidence. At the same time, we will offer some tips on what types of documents you might expect to encounter.

Next, we will offer some guidance on organizing your efforts. Because you are likely to encounter an overwhelming number of documents in your investigation, a system for organizing and collating them is very important. In the next section, we will offer a framework and some tips for creating an evidence-tracking system that will serve you well regardless of the size of the investigation.

Finally, we will discuss how to prove your case. Using the framework of logic and inference, we will explain how you can apply the organizational techniques you developed in the first two sections to prove cases. Marshaling the evidence toward proving one ultimate thesis—guilt—is an art; becoming good at it requires you first understand the process of legal proof.

Document Collection

All cases require submission of the best evidence. The term “best evidence” does not refer to the most appropriate piece of evidence for a particular claim. Instead, it means that all evidence submitted to prove a claim must be the original.1 Where the original is not available, the offering party generally must offer both evidence to show why it is unavailable and proof that the offered copy is accurate.2 There are some exceptions to this rule; however, it is wise to view it as being inflexible.

This rule is of particular importance to financial crime investigators. When attempting to prove that suspect “A” killed the victim by shooting him, production and introduction of the actual gun is usually a given. Conversely, when seeking to prove that CFO “A” embezzled money from the pension fund, introducing copies of bank statements and other documents might appeal to prosecutors. While under certain circumstances courts will allow this, proper collection and submission of the originals is usually required.

Therefore, proper handling of documents from the very beginning is your primary concern. From the moment documents come into your possession, regardless of how they were obtained, you will be ultimately responsible for their safekeeping and for their production. If you take the necessary precautions beforehand, this responsibility should be a simple matter to fulfill.

Sources of Documents

Although you probably will find documentary evidence in a number of locations, we have decided to divide them into three categories. First, you will obtain documents from the victim of the financial crime. Whether it is an investor swindled out of his pension or the multinational conglomerate that lost a million dollars, this is usually the first place you will look for documentary evidence. Next, you will seek to obtain records and documentary evidence from third parties. Finally, you probably will attempt to collect evidence from the suspect herself.

Collecting your documentary evidence in that order is usually advisable. As with everything we have discussed up to this point, when and from whom you first seek to collect evidence may vary depending on the operational circumstances; however, we have found that this logical sequence usually works very well.

DOCUMENTS FROM THE VICTIM

As soon as you receive the complaint or allegation, you should begin collecting documentary evidence. When you meet with the complainant, she will probably have some documentation available to substantiate her claim. If she does, collect it. While you may be tempted to instruct the complainant to hold onto the evidence until you make a more clear determination of viability, this could be problematic later on.

Although it is rare, documents sometimes get lost. If you allow the victim to hold on to the evidence and she misplaces, or worse, destroys it, the basis for your case may be gone. Likewise, there is the remote possibility that the original reporting party was complicit, but for some reason chose to initiate a complaint—perhaps to divert suspicion. If you allow the complaining witness to retain the evidence, destruction is possible if she later becomes a suspect. Finally, even if the complaining witness is not involved, the suspect may have accomplices in the company who have access to the documents. If so, removal, alteration, or destruction is a real danger.

Make copies and issue receipts. Sometimes, the complainant may be reluctant to release the documents. This is often the case with sensitive financial data or trade secret information. Nonetheless, it is important that you explain to the victim the need for proper evidence-handling procedures so that the court system can bring the guilty party to justice. Assure the victim that your evidence-handling procedures are as secure as or better than his own; then make the appropriate copies for his files and issue him itemized receipts for everything you take.

Be meticulous in your paperwork. While we have seen cases in which the investigator who collected documents took shortcuts and got away with it, do not test the limits of your liability insurance coverage. When the task of collecting hundreds of documents at a time confronts you, the natural inclination is to list groups of documents in bulk and lump everything together. Not only does this make identification of specific documents difficult, but it could trigger liability when the victim claims she released the company's most valuable trade secret to you and you cannot disprove it. The best advice is to take the time and list everything.

At the very minimum, you should leave with a statement. Even when the complainant has no documentary evidence to back the claim, you can still leave with something. Request that the complaining witness complete a written, signed statement. By doing this, you are establishing a basis for investigation as well as protecting yourself from future confusion. If the complaining witness recants, for whatever reason, you have something to verify the nature of the original complaint. Likewise, if the original witness is unavailable in the future, the statement, while unlikely to be admissible in court, can serve as a reference in her absence. Finally, even if the witness does not recant, she may alter her story or forget pertinent details. If you have them in writing, from the beginning, you have lost no ground.

Types of Documents to Expect

- Signed statements. Besides the original complainant, you should anticipate taking written statements from all witnesses at the victim business. These documents, while not substitutes for the actual testimonial evidence that the witnesses will offer later at trial, can serve as your outline of their likely trial testimony. In addition, the same cautions regarding complainant statements apply here.

- Transactional paperwork. This is another place where your pre-investigation planning will benefit you. Each business victim you encounter is likely to operate in a different manner. While most businesses have the same general flow of paper documents, there will be differences. Always be on the lookout for paperwork generated by the business that documents the various transactions that occur within its business cycle. Invoices, payment vouchers, and other original records of transactions are invaluable for tracking the flow of money.

- Intranet sources. In today's business world, more and more companies are establishing intranets that connect all employees and departments together. While this is a boon for productivity, it also can be a boon for you. Pay particular attention to chat facilities, weblogs, and other semipublic areas where suspects and witnesses may both lurk. While transactional information may not be available through these sources, they are often the unofficial communications channel in a firm. Background information, rumor, and gossip might prove to be a valuable place to begin looking for other clues.

- E-mails. Again, the rise of the company intranet and the growth of computer-based operations in business can be a boon to investigators. One area that has received considerable attention from the legal community recently is e-mail communications. Lawyers quickly have realized the value of e-mail communications, and more than one e-mail message has served as the smoking gun in civil cases. Many people treat e-mail correspondence with surprising flippancy, considering the longevity of most messages on the corporate server. Their carelessness can be your windfall.

Even though this list is not exhaustive, it is a good place to begin. As we mentioned, the record-keeping systems and paper trails generated will differ from business to business. However, preplanning and intelligence gathering should serve as a guide to knowing exactly what you are looking for. Whether the suspect religiously uses e-mail, or simply sends out traditional paper memos, both can be valuable sources of evidence. The key is remaining flexible and tailoring your search to the specific circumstances of each business.

DOCUMENTS FROM THIRD PARTIES

As a rule, in financial crime investigations the majority of documentary evidence you collect will come from third-party sources. In order for a financial criminal to be successful, he or she must interact with the traditional business world. The financial criminal must deposit money into banks, secure the advice of financial and legal professionals, and generally engage in the same type of conduct that noncriminals do. As a result, third parties become a very valuable source of information. Banks, accountants, and business and government organizations all have the potential to provide key pieces of evidence linking the suspect to the crime.

Remember, the diverse nature of business means that many different sources exist. Every business has a particular pattern of activity, and each has a circle of influence. In some cases, the contacts a business has may be limited to financial professionals. In other cases, the contacts will extend well beyond the financial sector into the community. Either way, keep in mind that the diversity of contacts the business has may dictate where you may find potentially incriminating documents.

Notwithstanding this diversity, we believe that a suspect's contacts can be broken down into five basic categories. First, the business or suspect undoubtedly will have contacts in the financial sector. These contacts can include banks, brokerage houses, and insurance professionals. Second, the suspect may have contacts within the professional community, including lawyers and accountants. Third, the suspect will have industry contacts such as business organizations, associations, and networking groups. Fourth, there will be contact between the suspect and the government, and finally, every suspect will have personal contacts, which, while not necessarily integral to the suspect's illegal activities, may still be a valuable source of information.

Because of the diversity we discussed earlier, instead of discussing the various sources of documents individually, we will address them by category. We will offer you some basic guidance about what you may expect to find, and we may even offer some tips about particular documents that are available. However, in terms of tailoring your search, we will leave you to your own devices, since there are, as we mentioned, an endless number of permutations of the information that you are likely to find.

Financial Contacts

Banks are often a great place to begin. Most criminals, if not all, will need to have some contact with organized financial institutions. Whether they need a simple checking account, or utilize the full panoply of financial services most banks now provide, there will be paper trails from which you can construct a picture.

Access to some bank records may be restricted. For example, currency transaction reports and other Bank Secrecy Act documents are strictly controlled through federal law.3 As a result, civil investigators, and to a much lesser extent local and state criminal investigators, will be limited in their ability to use these powerful tools. On the other hand, there are many bank and bank-related documents that civil investigators can obtain through civil summons and pretrial discovery tools. Likewise, local and state law enforcement investigators can obtain the majority of these documents through investigative and grand jury subpoenas and search warrants.

Do not overlook the nonobvious clues that banking records can reveal. Some inexperienced investigators may be tempted to focus immediately on the value that bank records have in proving income, or even documenting payments to business associates. As experience grows, an investigator routinely will find that bank records are valuable for many more things.

In addition to explicit information like amounts of cash flows, bank records hold metadata. Investigators loosely define metadata as a component of data that describes data: in other words, data about data.4 The metadata of a bank record set, then, are the data surrounding the transactions and their origin. For example, an item deposited into the suspect's account is more than an increase in cash. On the contrary, we can extract much more than that. By examining the date, time, teller information, and format of the transaction, we can extrapolate many important clues.

Taken together, metadata can establish our pattern of activity. By analyzing, either digitally or manually, all the transactions, we can build patterns that can give direction to the investigation. These patterns may lead us to other associates, or other assets, or even allow us to make predictions about future illegal acts.

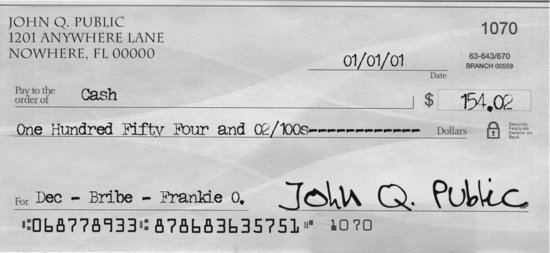

The metadata generated by each transaction can help reconstruct a suspect's movement. In addition to American Banking Association routing numbers, each check that goes through the clearing process collects additional clues. For example, during a counter transaction the teller will stamp the check with a unique transaction code, a time, a date, and the teller's information. Each of these codes may differ from bank to bank, but the bottom line is that each transaction is uniquely identifiable to a particular point in time. Included among these numbers are clues to the disposition of the funds and, in the case of deposits, the source of the funds. Exhibit 11.1 shows an example of some of these metadata.

Exhibit 11.1 Check Metadata

As you begin to evaluate banking transactions, it may be helpful to remember that there are essentially two categories of transactions. The first category, flow-through, is transactions that relate to the holder's account. For example, deposits, withdrawals, and debit/credit memos are all considered flow-through transactions. The second category encompasses the remainder of the banking transactions you are likely to encounter; we refer to them as nonaccount transactions, since they are not directly tied to a holder's account. Some examples of common nonaccount transactions are loans, CD transactions (excluding conversions of CD proceeds into an account deposit), third-party transactions, and safety deposit box transactions.5

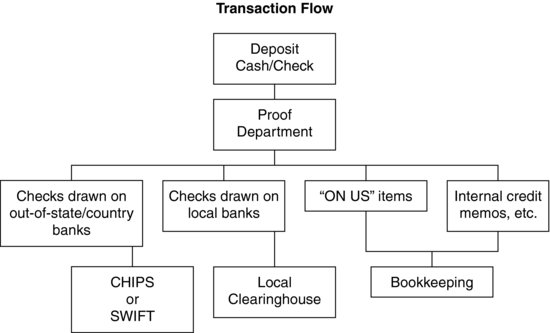

In order to extract the metadata necessary to formulate a hypothesis, it is also important to understand the basic progression of a flow-through transaction. Exhibit 11.2 shows the flow of an average transaction through the system.

Exhibit 11.2 Transaction Flowchart

Although you often will encounter loan files, securities statements, and other, nonaccount documentation, the greater portion of your analysis will involve flow-through transactions. Each transaction flows in generally the same way. First, there must be a transaction entry point. Usually, this is a window transaction where a suspect presents either an item for deposit or a draft for withdrawal, but it just as easily could take some other form such as an ATM or point of sale (POS) transaction. From the transaction entry point, the items proceed to the proof department where the teller's mathematical calculations are checked and the items are encoded with the bank's discrete identification numbers and the transaction-specific MICR information. From the proof department the transaction items are transferred to the microfilm department where all items are recorded and entered into the bank's computer system. From the microfilm department, the bank separates the transactions and then sends them to different departments for clearing.

Clearing is where the money changes hands. Depending on whether the transaction is an in-house transaction, meaning the item is presented against the institution on which the claim is held, or an outside transaction, the process may be more or less complicated. However, the general purpose of the clearing process is to ensure that at the end there is an exchange of claims between the payer and the payee. In the case of an in-house transaction, where the payer and payee institutions are the same, the transaction data are sent to the in-house clearing department, and then on to the bookkeeping department where the customer records are updated.6

If the transaction involves a local institution, the bank sends the transaction items to the local clearinghouse. When the parties to the transaction are local, usually within the same city, and the payer and payee institutions are not the same, the transaction items go to the local clearing department. These local checks usually are cleared through the Fedwire funds transfer system or the Clearing House for Interbank Payments System (CHIPS).7

The transit department ensures the proper clearance of outside-area transactions. The transactions that involve institutions outside the local area must be processed through alternative means. Depending on the origin of the issuing institution, this may be accomplished through either Fedwire, CHIPS, or, for most international transactions, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Transfers (SWIFT).8

What is a clearinghouse? While a detailed explanation of the history and role of clearinghouses in banking is well beyond the scope of this text, a few key principles are worth understanding. Clearinghouses act as a means to settle payments between financial institutions. With the rise in popularity of checks and bank drafts by merchants in the mid-1850s, banks needed a system for rapid, accurate, and efficient settlement between themselves. This system of interbank settlements facilitates the reconciliation of transactions between unrelated banks, making it a simple matter for one bank to process the drafts of another bank with confidence.9

Lastly, the bank routes those items that require special processing to the special handling department. Items such as wire transfers or debit or credit memoranda that require special handling by the institution are sent to this department. In those cases, the bank forwards the items to an internal department, often called the special handling department, for processing and posting to the customer's account.10

Once you have obtained and examined the flow-through records, you must analyze them. Analysis can take many forms, from manual to computer. Regardless of its form, the underlying rationale is the same. You must tailor your analysis to the nature of the crime you are investigating. Different crimes will have different patterns. Thinking through the methodology of the particular crime you are investigating will help you visualize patterns and types of transactions that you are most likely to find.

While each investigation will present you with different operational concerns, there are a number of similarities among them. You should look for both patterns and missing data. Patterns occur in accounts for a number of reasons, including legitimate things like paying monthly bills, and this is where the assistance of computer processing is helpful. By sorting the transactions by different criteria like payee, date, amount, and check number, you more easily can identify patterns and recurring transactions. Sorting is especially helpful in establishing the timing of transactions and may identify offense dates. For example, if your suspect's account, sorted by date, shows four months of recurring biweekly deposits with the same non-whole-dollar amounts, it is highly probable the transaction is his paycheck. Suddenly, in the third month, on the first Monday, the suspect deposits a large whole-dollar amount. This should be a red flag based on the previous pattern of activity. While it is no guarantee, it may pinpoint the date of a bribe, kickback, or blackmail payment.

In short, we recommend careful scrutiny of the intimate details as well as the broad picture. As we stated earlier, a thorough explanation of bank record analysis is beyond the scope of this introductory text. For a detailed account, we highly recommend A Guide to the Financial Analysis of Personal and Corporate Bank Records (1998), written by Marilyn B. Peterson, and published by the National White Collar Crime Center. It is highly instructive.

In addition to banks, insurance agents and stockbrokers are valuable sources of information. Insurance agents with whom the suspect has dealt are likely to have copies of insurance contracts and investment vehicles such as annuities and whole-life policies that can reveal additional sources of income. Likewise, brokerage firms can provide a wealth of information on the current and past financial status of the suspect. Activity in trading and margin accounts may reveal patterns or motives, and can help point you in the direction of other assets.

Professional Contacts

You should always interview professionals with whom the suspect has dealt. Attorneys are not known for their liberality when it comes to discussing their clients. Even so, there are occasions when a lawyer may be both forthcoming and enlightening. Notwithstanding the attorney–client privilege and work-product doctrines, there are matters within the knowledge of an attorney that he or she may in fact be able to tell you. While these times will be rare indeed, it is important to leave no stone unturned.

In addition, the attorney's fellow professional, the accountant, is often a much more fruitful target. In many jurisdictions, the accountant–client relationship falls outside the privileged information doctrine. Therefore, communications, both verbal and written, between a suspect and his accountant are both discoverable and admissible. As a result, you absolutely must question accountants, and if necessary compel them to produce all written documents pertaining to the client. The following is a list of a few of the documents that may be in the possession of your suspect's accountant:

- Working papers, which often identify sources of income, expenditures, hidden accounts, and loans

- Notes and memoranda used to prepare the suspect's income tax return

- Copies of income tax returns

- Corporate minutes and other corporate documents leading to the identification of shell companies

In short, nearly any financial document within the control of your suspect also might be available through his accountant. Rely on the meticulous record-keeping nature of most public accountants to provide a source of evidence.

Real estate professionals also may have records. Both real estate agents and title companies may have copies of contracts identifying real property that your suspect owns. Likewise, real estate and title companies commonly retain copies of insurance documents, settlement sheets, and copies of financial instruments used in consummating the transaction. These documents will show buyer/seller information as well as price, down payment, and the distribution of money at closing. Additionally, do not overlook the possibility that the real estate agent may be acting as a property manager. In the event the suspect retained the realtor in such a capacity, the realtor will have copies of items such as leases and tenant information.

Industry Contacts

Industry organizations can provide information that you may compare with your suspect's data. Most industry-based organizations maintain vast amounts of marketing and sales information for their industry. While the data they have likely will not be specific to your suspect, they may be valuable in determining things such as actual sales, expenses, and cost of goods sold. By obtaining the proper industry information, you can arm yourself with a yardstick by which to measure both the timing and amount of cash flows in the suspect's account. For example, while an association of video retailers will not have the specific number of monthly rentals your suspect transacted, they can tell you what the industry average is. In some cases, their information is specific to each region or city. Armed with that information, you are prepared to spot overstated revenues when examining your suspect's books.

Persons with whom the suspect does business have records, too. Both suppliers and customers will have transaction records documenting their relationship with the suspect. The nature of the relationship, frequency of contact, and general cooperativeness of the third party may determine the value of the documentation to the investigation. Do not overlook it. In some instances, you must take care to avoid eliminating a vendor/customer as a suspect too early in the investigation. Assuming the business contacts are legitimate, there are a number of documents of value in their possession. For example, purchase orders and invoices are a great way to disprove claimed sales figures or expenses. Likewise, unusual timing of invoices and unusually generous credit terms may tend to establish less-than-arm’s-length transactions and sham asset transfers. Do not hesitate to seek support for the vendor's documentation. For example, just because the suspect's supplier produces a paid invoice for 3,000 pizza boxes does not mean the transaction actually occurred. Backup data should exist in the vendor's file as well, indicating the depletion of inventory, reorder, and similar activities.

Sometimes what you do not see is just as important as what you do. As we said, information from invoices and purchase orders could be great evidence; however, do not overlook the ramifications of no evidence. If the suspect's office supply account reflects $35,000 in purchases over the course of the year, and the supplier of record has no invoices reflecting such purchases, you have just proven that the suspect inflated the business expenses—a manipulation often used by local money launderers.11

Government Contacts

Information that is useful to investigators fills government agencies. One of the purposes of government agencies and regulatory bodies is the collection of data. Agencies collect some of these data in the aggregate, such as census and accident data, but other portions of data are personal to the individual. The number of documents that a single individual generates in his or her lifetime is practically immeasurable, from a birth certificate, to marriage licenses, to corporate filings, to a death certificate; some oversight authority is responsible for their collection and processing. Many of these documents are public records, meaning they are open to inspection by the public.

Recently, there has been a general call for restrictions, but many documents are still readily available. On October 26, 1993, Representative James Moran introduced House Resolution 3365, which proposed a severe restriction on access to driver's license information.12 This resolution, later enacted and codified as Title 18, Section 2721, is known as the Driver's Privacy Protection Act and effectively limits access to driver's license information, with a few exceptions, to criminal justice agencies.13 In the comments to the resolution, Representative Moran expressed considerable concern over invasions of privacy leading to identify theft, stalking, and insurance fraud.14 Others have echoed Representative Moran's concerns. Even though this restriction does not affect law enforcement investigators, it does impinge on the investigative tools of the fraud examiner.

Notwithstanding this shift, there are a number of records that are still available. Aside from the limited class of records that fall within the purview of Section 2721, many public records are not only available but also easily accessible. As we mentioned earlier, the momentum of the Internet has swept up government no less than it has the public, and as a result most public agencies are moving toward making public records available online. In addition to the vast number of individual records scattered across cyberspace, there are a number of subscription-based services that will scour the public databases for you—for a price.

Whether you invest in shoe leather, scour the cyberworld yourself, or pay a service to do it for you, do not exclude public records from your search. By this point in the investigation, you likely have identified the county in which your suspect lives and works. That should be a good starting place. Likewise, your analysis of bank records, accounting documents, and insurance policies may have uncovered other counties, states, or even countries in which records may lie. Using this information, conducting your search in ever-widening circles is usually a solid strategy. Beginning with the suspect's county records and moving out from there, you should look for business, property, legal, and personal records.

- Business records. Businesses are highly regulated beginning at the local level. A minimum search would include looking for things such as occupational licenses; corporate registrations and filings; annual reports; state licenses from regulatory bodies such as real estate, mortuary, or banking commissions; and fictitious name registrations. In addition to licenses, regulatory agencies such as most state Departments of Agriculture record infractions and warnings for rule violations or failed inspections. Be sure to look at the names of all entities with which your suspect is associated. This process is one that you may have to repeat as more information about your suspect emerges linking him with new names and organizations.

- Property records. Depending on the jurisdiction, there are a number of names by which property records may be known. Likewise, some jurisdictions maintain separate files for recorded deeds and tax assessments. Both documents can be valuable as they might reflect nominee ownership of property or a fictitious transfer of property. Pay especially close attention to quit-claim deeds. While these instruments are both legitimate and common in real estate transactions, criminals can abuse them.

- Legal records. As with property records and other public documents, the rate at which individual jurisdictions make their systems available online is often related to their size and budget. However, in the past few years, even smaller jurisdictions have begun to place their court records on the web. In some cases, there are efforts to consolidate the records systems from all jurisdictions across the state into a single searchable database system. On the federal level, the PACER system, as well as other commercially accessible search engines, can provide access to all civil and criminal case filings. As a minimum, your search should include queries on both the businesses and given names of all suspects. You can expect to find records of all civil litigation in which the suspect was involved—as either plaintiff or defendant. You also may find all criminal actions, both felony and misdemeanor, and in some cases traffic infractions. Of particular note to a financial crime investigator are bankruptcy filings, which can be the mother lode in terms of either proving a starting net worth or establishing ownership of assets, not to mention revealing a motive for a theft in the first place.

- Personal records. It is important to include a search for all personal records of the suspect in order to ensure that you can account for all identities by which she may have been known. Whether it is a name change, or perhaps just a typographical error, Suzanne Benson is quite different from Susan Benton. By locating birth records, name change petitions, or other documents linking the two individuals as the same person, you can provide new avenues of inquiry in your business entity search.

Personal Contacts

As we mentioned earlier, partners, spouses, and exes of both can be useful information sources. While we find that personal contacts of the suspect are generally more valuable as interview subjects than producers of documentary evidence, do not discount their value altogether. For instance, personal contacts are often privy to the personal thoughts and ruminations of the suspect, which may end up in e-mail or conventional correspondence. If an evidentiary privilege does not cover the relationship, there is nothing wrong with obtaining it as a lead. Likewise, personal contacts may be valuable in helping to identify additional bank accounts. For example, repayment of a personal debt with a check may lead to discovery of a personal checking account that previously slipped below the investigator's radar. Therefore, while not usually the most productive of the sources, personal contacts can be viable and might even provide the clues that tie up the loose ends.

DOCUMENTS FROM THE SUSPECT

Suspects are usually the last people from whom you will seek documentary evidence. This is not always true, but in most cases you will attempt to secure documentary evidence from your other sources before striking out on a fishing expedition with your suspect. For a number of reasons, it is advisable to learn as much as possible about the business and personal habits of the suspect first. Sometimes, lack of this knowledge will cause you to miss documents, or, worse, mistake valuable evidence for irrelevant evidence, or, in the worst case, prematurely tip your hand to your suspect. Any of these scenarios is undesirable, each for its own reasons.

However, once you decide that your suspect is the next target of your document search, there are a few things to keep in mind. When you finally have the suspect in your sights in terms of document collection, you need to understand the limitations you may face. First, depending on the nature of your investigation, you may not have all the tools necessary. If the case is criminal, you have a full range of options, including subpoenas and search warrants. Conversely, if you are pursuing a civil investigation, your options may be somewhat more limited.

In a civil case, you are generally limited to civil process. While your criminal counterpart can rely on a court-issued search warrant (or in extreme cases a court-ordered wire intercept), you cannot. Although most third-party documents are available through civil process, documents in possession of the suspect may not be. In addition, due to the “voluntariness” of the civil discovery process, there is no guarantee that the suspect/defendant will produce the records, or even admit to their existence for that matter, upon your demand for production. Likewise, in many instances, the ability to invoke the civil process system is limited strictly to post-filing, meaning that the suspect must become a defendant before court jurisdiction will attach. Regardless of the nature of your investigation, whether civil or criminal, it is always advisable to consult with counsel prior to proceeding down this path. While we can offer some general guidance and suggest what documents are available, we cannot offer specific advice concerning the particular legal peculiarities of your jurisdiction.

One last comment on sources of documents: Do not overlook consensual production. Even though we mention this last, do not assume that it is any small item. In fact, consensual production of records, in both civil and criminal cases, is a deceptively powerful tool. As we have stressed throughout this text, do not overlook the obvious. Ask the suspect for the necessary records. You would be surprised at the number of suspects who are eager to produce the records. Whether it is out of stupidity or misbelief that they can somehow talk their way out of the mess, we have encountered more than a few suspects who willingly turned over some of the most inculpatory evidence in their case. Nevertheless, if the suspect is not inclined in that direction, then you may have to resort to more compelling means of getting what you want.

Document Organization

Now that we have introduced you to the nature of the records available, we need to talk about organizing them. Financial crime investigations result in more records and documents than perhaps any other type of case. The danger in this is the possibility of information overload. Coupled with this overload is the increased probability of loss and destruction. The existence of these dangers requires a very robust system of organization. Whereas some nonfinancial crime investigations can survive on a seat-of-the-pants approach, document-intensive cases cannot. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the organization and storage of your evidence long before you collect your first document.

Precollection

The key to any document organization system is a numbering and cross-reference system. When document counts run into the thousands of individual pieces of paper, perhaps the smoking-gun memo could get lost in the morass. Tracking documents allows investigators, and later prosecutors and jurors, to locate them, even when they are literally one-in-a-million.

Ideally, the creation of your numbering system should occur before you begin your first investigation. As with all things in life, the ideal is rarely the norm. However, the minimum should be the creation of a workable numbering system before you collect the documents of this particular case. In order to ensure that this happens, we recommend a standard scheme of numbering that you can use in each case.

Create a numbering/identification system. As a minimum, your numbering system should have flexibility. Whether you are searching a one-bedroom apartment, or a ten-office suite, you should still be able to use the same system. The ability to expand the numbering and cataloging system means you can use the system repeatedly without having to redesign it.

While not essential, we find descriptive numbering systems helpful. Personal preferences aside, the ease with which an outsider can identify the nature of each particular item may determine the success of your case— especially when the outsider is a prosecutor to whom you are trying to demonstrate the merits of your case. With a descriptive system, the unique alphanumeric identifier assigned to each item of evidence immediately notifies the recipient of its nature. For example, in a descriptive system, the alpha character “W” before the numeric components might designate all witness statements. Then, as the case grows, investigators involved in the case automatically will know that any reference to an item designated with a “W” refers to a witness statement. It is important to consider carefully the ramifications of your alpha designations before implementation to ensure that each identifier is in fact unique. If you use “W” for witnesses, and later accidentally use “W” for weapons also, the uniqueness will be destroyed.

Have a plan of attack. A general plan of attack can help ease the difficulty in seizing a large number of records. How you will obtain the documents you are collecting may dictate how you will attack the problem. If the documents you need will be coming through the mail in response to a subpoena, you can sort, catalog, and file them at your leisure. Conversely, if you are planning to execute a search warrant to obtain the records, often the chaos and time crunch associated with search warrant service will necessitate thorough planning to minimize errors.

Your plan also will vary depending on the nature of the target. If you are planning to search a small business with two employees housed in a two-room office suite, your search plan will vary considerably from that for a medical practice suspected of Medicaid fraud. For small offices and spaces where fewer documents and evidentiary items are expected, a standard search might be acceptable. However, high-volume or large-area spaces call for a coordinated search effort.

Sketch the search site and apply a grid. When dealing with a large area, it may be advisable to divide that area into sections using a grid overlay. You may either obtain a floor plan or sketch one yourself; the quality and scale of the drawing are relatively immaterial. Once you have sketched the floor plan, overlay it with a grid delineating a workable area. In lieu of the grid, assigning an identifying designation to each room may be sufficient. Generally, grids work well in large open spaces, and room designations work well in offices.

The area identifiers serve as collection guides. Regardless of whether you implement the grid method or room designation method, the unique identifier of each grid helps you in locating evidence later on. It also helps to promote an orderly canvass of the scene. Using the floor plan, you can search each individual grid, collecting evidence, and subsequently refer to its location relative to the room. For example, using the room designation, if a search of room “A” reveals an envelope of canceled checks in the first drawer of a lateral filing cabinet, the search warrant inventory and evidence/property receipt can identify its location as “Room A: Filing cabinet 1, drawer 1.” Later, during the investigation, you can easily recall the exact location in which you found that item.

Once you have planned for your document collection, you can move forward. Now that you have established a numbering system and planned how best to attack the search space, you can begin to focus on the actual search itself. While the rules of evidence are paramount, some considerations will make identification of potential evidence more efficient.

Collection

Searches require patience. Searches tend to take twice as long as anticipated and never seem to go as planned; having said that, we should note that planning and preparation make these inevitabilities less frustrating. As you begin your search, you must consider how you will secure the evidence you seize in order to preserve its value for trial, and ensure that you can account for it later in case you must return it to the suspect. Careful inventory and attention to detail are helpful here.

Secure and package all evidence. At the scene, the evidence should be carefully packaged and secured to ensure that no damage or alterations occur during transport. Whether you use individual storage boxes, envelopes, or something else, ensure that you carefully protect the items.

While a cursory inspection of the documents is necessary, analysis that is more thorough likely will have to wait. As the magnitude of the search increases, so too does the time crunch. While you must inspect the documents that you are seizing to ensure that the warrant authorizes their seizure, a closer examination will have to wait until later. If you succumb to the temptation of beginning your analysis on-site, the length of the search operation will expand beyond acceptable limits. The goal of the search should be the safe and efficient collection of all the items authorized under the particular warrant.

Once you have concluded the search, and provided the proper receipts to the suspect, you can transport the evidence back to the office for further evaluation at your leisure.

Storage

As mentioned earlier, evidence integrity is the key to your case. Issues of both civil liability and evidentiary admissibility hinge on the ability to establish that the evidence presented to the jury is in fact the authentic evidence obtained from the defendant. To ensure that these issues do not arise, you must properly store and work with the evidence. As mentioned earlier, markings or alterations directly on the evidence can preclude their admission in court. However, it is often important to assign unique numbers to individual pieces of evidence for identification purposes.

If this is necessary, you have several options. The first and often the most preferable option is to make photocopies of the document. These documents are no longer the best evidence, and you can alter, manipulate, and mark them as needed. A second option is to encase the evidence in some sort of packaging. In most instances, this material is a plastic bag. For example, there are a number of commercial products manufactured specifically to hold checks. You can then put the identifying information on the outside of the bag. In the third option, suggested by Marilyn Peterson in A Guide to the Financial Analysis of Personal and Corporate Bank Records, you may place a self-stick label on the documents for identification. While all three are legally acceptable, your operational objectives might make one more attractive than another. Regardless of which method you choose, it is important to remember that the integrity of the evidence is the overriding factor.

As we have cautioned the reader throughout this text, financial crime investigations are unlike most any other type of criminal investigation. They are fraught with complexity and are by nature information-intensive. Whether you are following the paper trail of a money-laundering organization or attempting to find the assets siphoned from the corporate bank account, you must follow the paper trail—a trail that often contains checks, bank statements, wire transfers, money orders, stock certificates, receipts, purchase orders, letters of credit, and possibly thousands more individual documents.

If you are lucky, your subpoenas, search warrants, and other documentary fishing expeditions will yield a plethora of information—so much so that the boxes of papers will fill your office (perhaps even the offices of your colleagues). This is, to put it mildly, a double-edged sword. Although everything you need to prove your case is contained in those boxes, they are worthless pieces of paper unless you can find exactly what you need when you need it. They are also worthless unless you can make them tell a compelling, persuasive story. Sitting in the boxes they offer nothing to your case.

The average nonfinancial crime probably has several hundred pieces of physical or documentary evidence (not considering major homicides, conspiracies, and organized crimes). However, many complex financial crimes have thousands of pieces of physical and documentary evidence.

The goal of any good investigation is to marshal the evidence in a way that tends to prove the ultimate theory of your case. In order to meet this goal, it is important to understand how you must arrive at the result. In order to understand that, it is first necessary to understand how to prove cases.

Investigators, as a rule, do not build their cases like lawyers; perhaps they should. If we can train investigators to think like lawyers (at least in terms of how to prepare and prosecute a case), we will help build a stronger case from the ground up. By investigating financial crime cases in this manner, not only will you present a more compelling case for prosecution, but you also will reduce the amount of superfluous work that tends to insinuate itself into the investigative process. The process of thinking like a lawyer begins with understanding how to build cases.

Everyone knows that in order to prove a case, the lawyer must prove that the defendant committed certain acts. Codified law and legal precedent usually define these acts, or elements, with relative clarity. In the case of criminal accusations, statutory laws codify the elements of the offenses. In the case of civil accusations, the elements of the offenses are uncodified and generally based on common law principles of stare decisis and judicial precedent. However, knowing the elements of the offense is only half the battle: Knowing how to reach that burden is the other half.

The Process of Proof

We prove legal cases through inferences. These inferences, built in chains, must lead logically from point A to point B. It is the strength, or weakness, of these inferences that determines the strength or weakness of the case. In legal argument, inference is the persuasive effect of each individual piece of evidence. From the existence of the evidentiary item, jurors may infer that some ultimate fact exists. We may think of proof, then, as the total net effect of the inferences that have been drawn. In other words, from evidence flow inferences, and from combined inferences flow conclusions. In the legal context, conclusions amount to proof.

As Exhibit 11.3 demonstrates, the ability to prove an ultimate fact rests solely on the strength of the inferences, not the evidence itself. This is true because regardless of the nature or volume of the evidence presented, if the inferences drawn are either incorrect or weak, we cannot reach the desired conclusion.

Exhibit 11.3 Role of Evidence

This notion may be new to some investigators. The difference is subtle, yet crucial. By bringing this critical distinction to your conscious thought, we hope to help you develop a better understanding of how to prove your case. The result will be better, more focused investigations.

Inference

Great lawyers (remember we are trying to teach investigators to think like lawyers), as distinguished from good ones, never forget that guilt is based on inference. Inference in turn relies on a chain of logic that must be forged one link at a time. Like proof of scientific theories, we must link together the inferences on which we base a finding of guilt in a logical, linear way. Unlike scientific discovery, however, legal proof must conform to a narrow framework of rigorously enforced rules. These rules, for the purpose of this text, revolve around relevance.

If this book were written for lawyers (real lawyers, not investigators thinking like lawyers), we would depart at this point and discuss the niceties of the rules of evidence and their admissibility. Because it is not, it will suffice to expound on the rules of evidence only far enough to say that we must confine our evidence to those things that are relevant. Of course, this does not mean that the investigator can totally disregard the bright-line rules of admissibility. Collateral uncharged crimes evidence and other highly prejudicial facts, as well as illegally obtained evidence, are inadmissible (under most circumstances) and should not be the object of your pursuit. However, you should leave the finer details of these legal principles up to the prosecutor—a highly trained legal practitioner.

Relevance

In short, evidence is relevant if it tends to either prove or disprove an issue in contention. For example, if the question of whether the sun is shining were the ultimate question, the fact that it is ten o’clock in the morning would appear highly relevant. The fact that it is January 17, 2003, would not.

The confusion over relevance versus irrelevance arises because we rarely prove cases under a singular line of logic. What first appears to be a singular question—did the suspect take the money?—is ultimately misleading. Instead, each ultimate question contains subquestions. Collateral lines of logic can work together to blur the issue of relevance. A fact may not immediately appear to be relevant to the ultimate question at issue; however, when the ultimate question is broken down into its component subquestions, the relevance of the fact becomes clearer.

In our sun-is-shining hypothetical, the reference to date at first may have appeared obtuse. However, if we reformulate the question into its subquestions, date might be more important. Implicit in this question is the assumption that we are referring to an observation at our current location. If our current geographic reference point is Nome, Alaska, date suddenly becomes important since Nome's hemispheric location limits the dates on which the sun is shining at ten o’clock in the morning: from irrelevant to relevant in one easy step. Clearly, this is a simplistic example. No doubt, many of our readers instinctively saw the relevance of the date fact; however, legal questions are rarely so transparent.

To understand fully how to effectively build this chain of logic, the investigator must grasp the nature of the logic underpinning the legal argument. There are several forms of logical argument; the two that we are most concerned with in the context of legal proof are deductive and inductive.

The Logic of Argument

Deductive Argument

Deductive reasoning is a form of argument that works from the general to the more specific; we often refer to this as “top-down” logic. Inductive reasoning, on the other hand, works from specific observations to the broader and more general; we sometimes call this “bottom-up” reasoning.15

An argument stated deductively offers two or more rules or assertions that lead automatically to a conclusion. This syllogistic form of argument, first propounded by Aristotle, is designed to produce mathematical certainty. The use of syllogisms, or mathematical statements, ensures that the lines of argument lead logically to the conclusion.16

A deductive argument has, at a minimum, three statements: the major premise, the minor premise, and the conclusion. The first statement, or the major premise, is a statement of general truth dealing with categories rather than finite objects. Contained within the major premise are two sections: the antecedent and the consequent.17

The antecedent phrase is the subject phrase, and the consequent phrase is the predicate. For example, the statement, “all men are mortal,” contains the antecedent phrase, “all men” (the general category), and the consequent phrase, “are mortal.”

The second statement, the minor premise, is a statement about a specific instance encompassed by the major premise. For example, the phrase, “Socrates is a man,” is a statement of truth dealing with a specific instance governed by the major premise.18

The third statement, the conclusion, must follow naturally from the relationship of the major and minor premises to each other. If no deductive fallacies exist, this statement will be the inescapable result of the first two statements. In the above example, “Socrates is mortal,” is the natural and inescapable conclusion to the major and minor premises.19

In forming deductive arguments, we can relate the minor premise to the major premise in four different ways. Only two produce sound logical arguments; the other two produce deductive fallacies.

The structure in our illustration is an example of affirming the antecedent. In this form, the minor premise asserts that a particular instance is an example of the major premise's antecedent. In our example, we are asserting that Socrates is indeed a man. We are affirming that Socrates and the state of being a man are equal.

We refer to the converse of this form as denying the consequent. In order to construct a deductive syllogism in which we deny the consequent, we must assert that a particular instance does not equal the consequent. Our major premise, “all men are mortal,” may remain the same. However, the minor premise must change.

If, instead of asserting that Socrates is a man, as we did in affirming the antecedent form, we deny that a specific object is mortal—“my car is not mortal”—we have constructed the second sound syllogistic argument. From this minor premise logically follows the conclusion that “my car is not a man.”20

The strength, or soundness, of a deductive argument rests on the truth of the major and minor premises. If the first two statements are true, the conclusion must be correct. However, a sound argument does not necessarily guarantee the truth of the conclusion. If either the major or minor premise is false, we will still reach an incorrect conclusion using sound syllogistic logic.

Inductive Argument

In contrast to the mathematical precision of deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning is not designed to produce certainty. This form of logical argument uses a series of observations in order to reach a conclusion. We combine these observations, often referred to as a chain of observations, with previous observations to reach a defensible conclusion.21

Of the three basic forms of inductive reasoning, induction by enumeration, or generalization, is the most common.22 In this form, you make a general statement regarding some predicted outcome based on observations of a specific instance of a class. For example, the statement, “all lawyers are sleazy,” when based on your observation of the last three lawyers you have encountered, would be induction by enumeration.

Because inductive logic is less precise than deductive logic, fallacies often are less easily identified. The fallacy most commonly associated with inductive reasoning is the hasty generalization.23 When an argument fails as a hasty generalization, the inductive leap that the proponent asks the decision maker to make is too remote. Sufficient evidence does not support it. The following statement suffers from the fallacy of hasty generali-zation:

XYZ Company is an import-export company operating from Miami, Florida. It is involved in money laundering.

This statement may or may not be true. There is insufficient evidence based on this statement to draw the conclusion. It is possible that the statement is true, but the leap from XYZ Company's existence as an import-export business in Miami to the conclusion that it is laundering money is much too broad to make with any certainty.

A second common fallacy associated with generalization is exclusion. Exclusion occurs when we omit important pieces of information from the chain. Put simply, alternative explanations for reaching the conclusion have been excluded.24 For example, consider the following argument:

The police found a dead body with three bullet wounds.

It would be a safe, albeit not mathematically certain, conclusion that the person found by the police died because of his gunshot wounds—that is, unless we also knew that the body was missing its head.

Although it is still possible that the victim died of gunshot wounds and that the decapitation was inflicted postmortem, it is equally possible that the manner of his death was decapitation and someone administered the bullet wounds postmortem for some other purpose. The fallacy of exclusion forces the decision maker into reaching a false conclusion owing to lack of relevant alternative evidence.

Inductive versus Deductive Reasoning in Case Proof

As you can see, inductive and deductive reasoning are very similar, the greatest difference being the manner in which we express the argument. When you argue from the general to the specific, deductive reasoning is in play. When you reason from the specific observation to broader generalizations, inductive logic is in play. It is important to note that we may recast all inductive arguments as deductive syllogisms, and vice versa.

As an investigator, you will encounter both forms of logical reasoning. However, the offering of evidence in the legal system most often will expose you to inductive logic. In the process of proof, it is common to allege and prove specific isolated facts and build to a general conclusion. Therefore, the inductive process of moving from the specific observation to the general conclusion just seems to feel right.

We should note that some readers may argue that deductive reasoning, being the more mathematically certain, should be the more favored logical form in legal proceedings. Keep in mind that the law, and the system for legal resolution of disputes, is concerned with probabilities, not certainties. It is not absolute proof that we seek; it is proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Because inductive reasoning is ideally suited to reason from specific facts (evidence) toward broad generalizations (guilt or culpability), induction is the more natural form of legal argument. In truth, it does not matter greatly which form the argument takes. As stated earlier, we may form all arguments as either inductive or deductive premises.

That is not to say that deductive reasoning is useless in the legal context. Quite the opposite is true. When we choose the deductive over the inductive, the inferential focus shifts. There are still inferential leaps that you must make; we simply make them in a different location.

For example, we can formulate our argument regarding XYZ Company's activities either way. To state the argument inductively: XYZ Company is involved in money laundering since it is an import-export company operating in Miami, Florida.

Stated as syllogisms: (1) All import-export companies operating in Miami, Florida, are involved in money laundering. (2) XYZ Company is an import-export company located in Miami, Florida. (3) Therefore, XYZ Company is involved in money laundering (deductive).

Obviously, these examples are oversimplified, exposing the fallacies of logic quite quickly. In reality, the inferential links in a logical chain will be much more subtle, and the facts often obscure the fallacies of logic that can cripple the argument.

Both arguments, as they stand, are legally indefensible. In the inductive example, the inferential leap may not be as evident as in the deductive, requiring the reader to infer that all import-export companies operating in Miami, Florida, are engaged in money laundering. Although the reader undoubtedly senses that something is not quite right, specifically pinpointing the source of the illogicality may be difficult.

In the deductive example, the breadth of the inferential leap required of the reader is much more apparent. By breaking the proposition down into deductive form, we more easily expose the fallacies of logic inherent in the inductive process.

Based on our previous discussion, and the fact that the process of legal determination revolves primarily around inductive logic, your job as investigator requires you to guard against the fallacies associated with its use. The danger of the two most common fallacies, hasty generalization and exclusion, can be reduced by carefully analyzing the line of argument and the inferences leading to proof of specific legal elements.

As noted above, we build all legal arguments on inference. However, it is rare for a legal argument to be based on one single inference. Instead, we pile many inferences one on the other until the ultimate proposition—usually guilt or innocence—is the inescapable conclusion. We refer to this chain of inferences as compound, or catenate, inferences.25 The strength or weakness of the legal argument is determined by the granularity of this chain of inferences. The finer the grain is (the shorter the inferential leap), the more powerful and persuasive the argument becomes.

Understanding the complexities and dynamics of inferential logic is essential to properly investigating a case. During the investigative stage, the investigator must remain cognizant of the intermediate inferential steps between the evidence that exists and the ultimate issue. Only by careful dissection of the intermediate inferences within the chain can we determine the location of the possibility of doubt. This explicit analysis of the catenate inferences is the greatest safeguard against fallacious reasoning an investigator possesses.

Proof through Inference

The inferential weight of evidence can range from weak to strong depending on how clearly we can draw the inference from the existence of the evidence. Weak inferences exist when the leap from evidence to conclusion is great. Conversely, strong inferences are generated when the leap from the evidence to the conclusion is short. A weak inferential relationship exists between the evidentiary statement, “The defendant and his ex-wife were hostile toward each other,” and the conclusion that the defendant killed his ex-wife. A strong inferential relationship exists between the statement, “I saw the defendant stab his ex-wife,” and the conclusion that the defendant killed his ex-wife.

In the first case, there is too great a leap between the statement and the conclusion—there are too many intervening steps. In the second case, there are no, or at least very few, intervening steps between the evidentiary statement and the conclusion. The goal of the investigator is to reduce the distance between intervening steps between the defendant and the conclusion.

We reduce this distance by creating a chain of inferences referred to as concatenate inferences.26 Concatenate inferences build one upon the other until ultimately they reduce the chasm between the defendant and the conclusion to a manageable distance. We are not shortening the overall distance human reasoning must travel; rather, we are merely breaking it up into smaller steps.

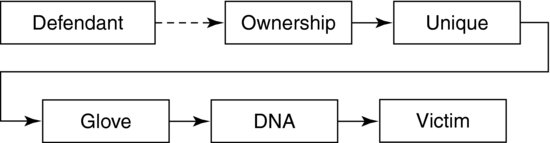

We can illustrate this process by concocting a hypothetical situation. Assume we wish to link the defendant to the murder of his ex-wife. Initially, the connection—the inferential relationship—between the defendant and the victim is weak, as shown in Exhibit 11.4.

Exhibit 11.4 Initial Relationship of Defendant to Victim

We may argue for the inference that because the defendant and the victim knew each other and were divorced, the defendant had a motive to kill her. It is a plausible theory, yet not very strong—certainly not strong enough to proceed to trial. How can we strengthen this inferential relationship? We must build our chain.

Our investigation has uncovered a bloody glove at the crime scene. Immediately, there is an inference that the glove is somehow involved in the murder. If we later learn that the DNA from the blood on the glove matches that of the victim, the inferential relationship between the glove and the murder becomes very strong, as shown in Exhibit 11.5.

Exhibit 11.5 Building the Inference Chain

Although the connection between the defendant and the victim is still tenuous (as indicated by the dashed line in Exhibit 11.5), the connection between the victim and the glove is strong. Obviously, we are not satisfied. Our investigation continues.

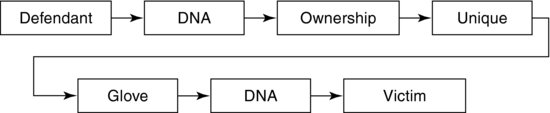

The forensic examiners at the crime lab have determined that the gloves are in fact a very expensive brand sold only in exclusive upscale department stores. They are so exclusive that the store has sold only 25 pairs in the past year. This information alone does not necessarily strengthen the inferential relationship to the defendant. However, taken in combination with the fact that department store records show that two months earlier the defendant purchased a pair of these gloves using his credit card, we are slowly strengthening our chain.

Exhibit 11.6 illustrates the evolving inferential relationship. We have still depicted the link between the glove and the defendant in a dashed line. Although there is a good connection between the two, 24 other people have a connection to the gloves, at least hypothetically.

Exhibit 11.6 Strengthening the Chain

Finally, our forensic experts compare the DNA from skin cells found in the glove's lining with those of the defendant and they match. This final piece of evidence is the link we have been waiting for. Until now, we could link the defendant inferentially as an owner of similar gloves. Now, we can link him as the owner of these gloves. Exhibit 11.7 illustrates the completed inferential chain.

Exhibit 11.7 Completed Inferential Chain

We can now depict the relationship between the defendant and the victim with solid lines. Does this mean that we have proven that the defendant murdered the victim? Of course not; all it proves is there is a strong inference that a glove owned by the defendant was found at the scene of the murder with the victim's blood on it. Such is the nature of inferential proof. Is this chain of inferences strong enough to convict the defendant of murder? Only the jury can answer that question.

As you can see by this simplistic example, the job of the investigator is not to prove that the defendant committed the crime. The investigator's job is to construct a chain of inferences sufficiently strong to convince a fact-finder that the desired conclusion is the most plausible sequence of events. In order to do that, you must internalize the distinction between evidence and inference.

Hidden Inferences

Until now, we have been discussing only explicit inferences—those inferences that the investigator directly urges. For example, the inference that the glove was involved in the murder is an explicit inference because the investigator has asserted the fact that we found DNA belonging to the victim on the glove. There are, however, other inferences that are of concern to the criminal investigator; they are hidden, or implicit, inferences.

The evidence does not directly urge an implicit inference; instead, implicit inferences tag along as baggage. An example of an implicit inference that the investigator expects the jury to draw involves the ownership of the gloves. Before introducing evidence that we found the defendant's DNA inside the glove, we drew an ownership inference based on the credit card purchase.

The inference was a reasonable one. However, implicit in that inference was the assumption that the defendant, not someone using his credit card, had purchased the gloves. If we lay bare this implicit inference, a weakness in our inferential chain becomes apparent. Our link between the defendant and the murder, absent the DNA-glove evidence, weakens when we consider the alternative possibility that someone using the defendant's credit card purchased the gloves. By ignoring the implicit inference, we leave the flank of our logical line of argument open for counterattack.

Generalizations

Closely related to the implicit inference is the generalization. A generalization is merely an implicit inference that most people generally recognize. For example, most people accept the generalization that dropped objects fall. Therefore, an eyewitness account of the victim being pushed from a tall building, coupled with the recovery of the body at the base of the building, will urge the jury to conclude that the defendant died as the result of the fall. Implicit in this conclusion are the hidden inference that there were no intervening causes of death (no one shot the victim on the way down) and the generalization that gravity acted upon the body, propelling it downward. Both implicit inferences in this scenario are quite reasonable and in fact relatively safe from attack; not all generalizations are so bulletproof.

Generalizations become especially dangerous when trained investigators make them. This is true because investigators draw very specific conclusions from random facts based on their experience and training. Juries in general do not possess the same training and experience and may not draw the same generalized conclusion. The nature of generalizations makes them so dangerous.

We also might call a generalization an assumption based on experience. The key, then, is the fact that people have a broad range of experiences and may or may not make the same assumption given the facts. As Lawrence Lessig put it, facts derive their meanings from “frameworks of understanding within which individuals live.”27 It is this diversity of experience that makes ignorance of the existence of implicit generalization, or reliance on common sense, so dangerous to the process of logical proof.

Like it or not, common sense plays an integral role in judicial determination. The legal rules guide the formation of our original legal hypothesis. Our common-sense understanding of the world ultimately grounds these. Common sense, however, may be problematic. Not all common-sense assumptions are legitimate grounds for the interpretation of evidence.

Common sense, although implicit in any legal context, can cause inferential errors. For example, common sense can be culturally specific. Assumptions, based on culturally specific common-sense principles, can cause grave inferential errors. One result of common-sense inferential logic is tunnel vision in police investigations.

This does not necessarily mean that a single generalization in your line of argument will doom it to failure. It does mean that broad generalizations may leave your otherwise airtight logical chain vulnerable. As an investigator, it is imperative that you guard against assuming that the jury will draw implicit inferences and generalizations. The only way to guard against them is to recognize them. The only way to recognize them is to analyze carefully the entire logic of the case.

Conclusion

Evidence proves the case. How you collect evidence and what you recover has a direct relationship to whether you will prove your case. Likewise, the logical underpinning of your case dictates whether the jury will reach the same conclusion you want them to. In this chapter, we first discussed the evidence you are likely to encounter in a financial crime investigation, then we offered some practical advice on how to collect the evidence in an organized and defensible way. Finally, we offered some insight into how we prove cases through inference and demonstrated that the evidence we have collected must build the chain of inferences. In doing this we hope to have provided you with a stronger foundation in the process of legal proof.

Suggested Readings

Abimbola, K. “Abductive Reasoning in Law: Taxonomy and Inference to the Best Explanation.” Cardozo Law Review 22 (2001): 1683–89.

Abimbola, K. “The Logic of Preliminary Fact Investigation.” The Journal of Law and Society 29 (2002): 533–59.

Allen, R. J. “The Nature of Juridical Proof.” Cardozo Law Review 13 (1991): 373–401.

Allen, R. J., and A. Carriquiry. “Factual Ambiguity and a Theory of Evidence Reconsidered: A Dialogue between a Statistician and a Law Professor.” Israel Law Review 31, nos. 1–3 (1997): 464.

Arthur, W. B. “Inductive Reasoning and Bounded Reality.” American Economic Review 84 (1994): 406–11.

Binder, D., and P. Bergman. Fact Investigation: From Hypothesis to Proof. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing, 1999.

Cohen, L. J. The Introduction to the Philosophy of Induction and Probability. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Eco, U. Semiotics and the Philosophy of Language. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Eco, U. A Theory of Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976.

Eco, U., and T. Sebok, eds. The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes & Pierce. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983.

Finkelstein, M., and W. Fairly. “A Bayesian Approach to Identification Evidence.” Harvard Law Review 83 (1970): 489–517.

Franklin, J. The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability before Pascal. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Hastie, R., and N. Pennington. “The O.J. Simpson Stories: Behavioral Scientists’ Reflections on The People of the State of California v. Orenthal James Simpson.” University of Colorado Law Review 67 (1996): 957–76.

Huygen, P. E. M. “Use of Bayesian Belief Networks in Legal Reasoning” (Presented at Seventeenth BILETA Annual Conference). Amsterdam: Computer Law Institute, 2002.

“In Praise of Bayes.” Retrieved March 25, 2003, from the University of California, Berkeley, Computer Science Division website, September 30, 2000, www.ai.mit.edu/~murphyk/Bayes/economist.html.

Josephson, J., and S. G. Josephson. Abductive Inference Computation, Philosophy, and Technology. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Kadane, J., and D. A. Schum. A Probabilistic Analysis of the Sacco and Vanzetti Evidence. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1996.

Kaye, D. H. “Bayes, Burdens and Base Rates.” International Journal of Evidence and Proof 4, no. 4 (2000): 260–67.

Kaye, D. H., and J. J. Koehler. “Can Jurors Understand Probabilistic Evidence?” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 154, part 1 (1991): 75–81.

Ketner, K. L., ed. Pierce and Contemporary Thought: Philosophical Inquiries. New York: Fordham University Press, 1995.

Koehler, J. J. “The Base Rate Fallacy Myth.” Psycoloquy, 4, article 93.4.49.

Lempert, R., S. Gross, and J. Liebman. A Modern Approach to Evidence. St. Paul, MI: West Publishing, 2000.

Leonhardt, D. “Adding Art to the Rigor of Statistical Science.” New York Times (electronic version), April 28, 2001.