CHAPTER 10

Swaps

Introduction

What exactly is a swap transaction? As the name suggests, it entails the swapping of cash flows between two counterparties. There are two broad categories of swaps: interest-rate swaps and currency swaps.

In the case of an interest-rate swap (IRS), all payments are denominated in the same currency. The two cash flows being exchanged will be calculated using different interest rates. One party may compute its payable using a fixed rate of interest and the other may calculate what it owes based on a market benchmark such as LIBOR. Such interest-rate swaps are referred to as fixed–floating swaps. A second possibility is that both payments may be based on variable or floating rates. The first party may compute its payable based on LIBOR, whereas the counterparty may calculate what it owes based on the rate for a Treasury security. Such a swap is referred to as a floating–floating swap. It should be obvious to the reader that we cannot have a fixed–fixed swap. Consider a deal in which Bank ABC agrees to make a payment to the counterparty every six months on a given principal at the rate of 5.25 percent per annum in return for a counterpayment based on the same principal computed at a rate of 6 percent per annum. This is an arbitrage opportunity for Bank ABC, because what it owes every period will always be less than what is owed to it. No rational counterparty will therefore agree to be a party to such a contract. In the case of an interest-rate swap, before the exchange of interest on a scheduled payment date, there must be a positive probability of a net payment being received for both parties to the deal.

In the case of an interest-rate swap, a principal amount needs to be specified to facilitate the computation of interest. But there is no need to physically exchange this principal at the outset. Therefore, the underlying principal amount in such transactions is referred to as a notional principal.

Let us consider a currency swap. Such a contract also entails the payment of interest by two counterparties to each other, the difference being that the payments are denominated in two different currencies. Because two currencies are involved, there are three interest-computation methods possible: fixed–fixed, fixed–floating, and floating–floating. Examples 10.1 and 10.2 illustrate this.

Two banks that are parties to a swap deal. Bank Exotica agrees to pay interest to Bank Halifax at the rate of 6.40 percent per annum on a principal of $2,500,000. In return, the counterparty agrees to pay Bank Exotica an amount that is computed on the same principal but that is based on the LIBOR prevailing at the outset of the payment period. This is a fixed–floating swap. We will assume that interest is payable at the end of every six months for a period of two years.

Assume that the observed values of LIBOR over a two-year horizon are as depicted in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1 Six-Month LIBOR as Observed at Six-Month Intervals

| Time (Months) | LIBOR (per Annum) (%) |

| 0 | 6.20 |

| 6 | 6.55 |

| 12 | 6.75 |

| 18 | 6.10 |

We will assume that the LIBOR used for computing the interest payable for a period will be the value observed at the start of the period, although the interest per se is payable at the end of the period. This is the common practice in financial markets and is referred to as a system of determined in advance and paid in arrears. Rarely are we likely to observe a case of determined in arrears and paid in arrears. The second method entails payment based on the LIBOR prevailing at the end of the period for which the interest is due.

The periodic interest payable by Bank Exotica is

![]()

This amount will be invariant for the life of the swap for two reasons. First, the bank is paying interest based on a fixed rate. Second, we are assuming that every six-month period corresponds to exactly one-half of a year. The gap between successive interest-payment dates may vary and depends on the day-count convention that is assumed.

The periodic interest that is payable by Bank Halifax will vary because the benchmark rate is variable. The interest payable by the bank for the first period is

![]()

The net transfer at the end of the first six-month period is a cash flow of $2,500 from Bank Exotica to Bank Halifax.

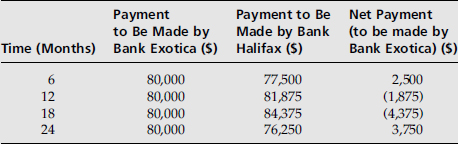

The amounts payable by the two banks and the net payment at the end of every period are given in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2 Amounts Payable by the Two Counterparties

Consider the last column of Table 10.2. It describes the net payment to be made or received by Bank Exotica. Positive amounts indicate that Bank Exotica will experience a cash outflow: what it owes is more than what it is owed. Amounts in parentheses indicate a net cash inflow: what the bank owes is less than what is owed to it.

We consider a currency swap. Bank SudAfrique enters into a swap with Bank Oriental with the following terms. The two banks will first exchange South African rands (ZAR) for U.S. dollars (USD) at the rate of 7.50 USD–ZAR. The principal amount in USD is $2,400,000 and is payable by Bank Orient in exchange for the South African currency. Every six months thereafter, Bank Sud Afrique will pay interest at the rate of 4.75 percent per annum on the principal amount of $2,400,000. Bank Orient, on the other hand, will pay interest at the rate of 7.25 percent per annum on the equivalent amount in ZAR. The terms of the deal specify that the two banks will exchange back the currencies at the end of two years at the original spot rate.

Table 10.3 shows the cash flows payable and receivable by the two banks.

Table 10.3 Cash Flows for a Fixed–Fixed Currency Swap

Contract Terms

In swap contracts such as those discussed previously, certain terms and conditions need to be specified at the very outset to avoid ambiguities and potential future conflicts.

Every swap contract must spell out the identities of the two counterparties to the deal. In our first illustration, the two counterparties are Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax; in the second, they are Bank Sud Afrique and Bank Oriental.

The tenor or maturity of the swap refers to the date on which the last exchange of cash flows between the two parties will take place. In both preceding illustrations, the tenor was two years. Unlike exchange-traded products such as futures contracts, in which the exchange specifies a maximum maturity for contracts on an asset, swaps being over-the-counter (OTC) products can have any maturity that is agreed on in bilateral discussions.

The interest rates on the basis of which the two parties have to make payments should be spelled out. To avoid ambiguities, the basis on which both cash inflow and cash outflow are arrived at for both counterparties should be explicitly stated.

In the case of the preceding interest-rate swap, Bank Exotica was a fixed-rate payer with the interest rate fixed at 6.40 percent per annum. Bank Halifax was a floating-rate payer with the amount payable based on the 6-month LIBOR prevalent at the start of the interest-computation period.

For currency swaps, we also need to specify the currencies in which the two parties will make payments to each other, in addition to the specification of interest rates to be adopted by them. In the preceding illustration of a currency swap, Bank Sud Afrique was a fixed-rate payer with the interest being payable in U.S. dollars at the rate of 4.75 percent per annum. Bank Oriental also was a fixed-rate payer, the difference being that it was required to pay interest in South African rands at the rate of 7.25 percent per annum.

The frequency with which the cash flows are to be exchanged has to be defined. In our illustrations, we assumed that cash-flow exchanges would take place at six-month intervals. In the market, such swaps are referred to as semi–semi swaps. Other contracts may entail payments on a quarterly basis or annual basis. The benchmark that is chosen for the floating-rate payment is usually based on the frequency of the exchange. A swap that entails the exchange of cash flows at six-month intervals will specify six-month LIBOR as the benchmark, whereas a swap that entails the exchange of payments at three-month intervals will specify the three-month LIBOR as the benchmark. The most popular benchmark in the market is the six-month LIBOR.

The day-count convention that is used to compute the interest must be explicitly stated. In our illustration, we assumed that every six-month period amounted to exactly one half of a year. The underlying convention is referred to as 30/360: every month is assumed to consist of 30 days, and the year as a whole is assumed to consist of 360 days. Other possibilities include actual/360 or actual/365.

The principal amounts that serve as the basis for each party to figure out payments to the counterparty have to be stated. In the case of interest-rate swaps, there is only one currency involved. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the principal has to be specified to facilitate the computation of interest. In the case of currency swaps, the two currencies involved and the principal amounts in each have to be specified. In other words, the rate of exchange for conversion between them should be stated.

Market Terminology

We first consider interest-rate swaps. As we discussed, there are two possible counterpayments: fixed–floating and floating–floating. A swap in which one of the rates is fixed is referred to as a coupon swap. On the other hand, a swap in which both the parties are required to make payments based on varying rates is referred to as a basis swap. The IRS that we considered previously is a coupon swap: Bank Exotica was required to pay a fixed rate of 6.40 percent per annum in exchange for a payment from Bank Halifax that was based on LIBOR.

In a coupon swap, the party that agrees to make payments based on a fixed rate is the payer, and the counterparty that is committed to making payments on a floating-rate basis is the receiver.1 However, these terms cannot be used in the case of basis swaps, because both cash-flow streams are based on floating rates. It is important to be explicit and to avoid ambiguities. For each counterparty, both rates—for making and receiving payments—should be explicitly stated. In the case of the interest-rate swap that we previously considered, the terms would be stated somewhat as follows.

Counterparties: Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax

- Interest rate 1: A fixed rate of 6.40 percent to be paid by Bank Exotica to Bank Halifax.

- Interest rate 2: A variable rate based on the six-month LIBOR prevailing at the onset of the corresponding six-month period to be paid by Bank Halifax to Bank Exotica.

Key Dates

There are four important dates for a swap. Consider the two-year swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax. Assume that the swap was negotiated on June 10, 2010, with a specification that the first payments would be for a six-month period commencing on June 15, 2010. June 10 will be referred to as the transaction date. The date from which the interest counterpayments start to accrue is termed the effective date. In our illustration, the effective date is June 15.

By assumption, our swap has a tenor of two years; the last exchange of payments will take place on June 15, 2012. This date will be referred to as the maturity date of the swap. We will assume that the four exchanges of cash flows will occur on December 15, 2010; June 15, 2011; December 15, 2011; and June 15, 2012. The first three dates on which the floating rate will be reset for the next six-month period are referred to as reset or refixing dates.

Inherent Risk

An interest swap exposes both the parties to interest-rate risk. Consider the fixed–floating swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax. For the fixed-rate payer, the risk is that the LIBOR may decline after the swap is entered into. If so, although the payments to be made by it would remain unchanged, its receipts would decline in magnitude. From the standpoint of the floating-rate payer, the risk is that the benchmark—in this case, the LIBOR—may increase after the swap is agreed on. If so, even though its receipts would remain unchanged, its payables would increase. A priori we cannot be sure whether LIBOR will increase or decline. Ex ante, both the parties to the contract are exposed to interest-rate risk.

The Swap Rate

What exactly is the swap rate? The term refers to the fixed rate of interest that is applicable in a coupon swap. There are two conventions for quoting the interest rate. The first practice is to quote the full rate in percentage terms. This is referred to as an all-in price. In certain interbank markets, however, the practice is to quote the fixed rate as a difference or spread in basis points between the fixed rate and a benchmark interest rate. The benchmark that is used is the yield for a government security with a time to maturity equal to the tenor of the swap. Example 10.3 best describes the two methods.

Illustrative Swap Rates

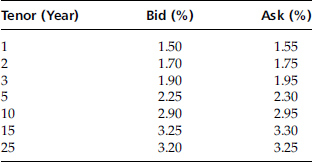

Consider the hypothetical quotes for euro-denominated interest-rate swaps on a given day as shown in Table 10.4. Assume that the corresponding floating rate is the six-month EURIBOR (Euro Interbank Offered Rate).

Let us consider the interest-rate swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax in which the former agreed to pay a fixed rate of 6.40 percent per annum. Such a specification is a manifestation of an all-in price because the fixed rate is quoted in full.

Consider an alternative scenario in which the yield to maturity for a 2-year T-note is 5.95 percent per annum. If so, the spread will be quoted as 45 basis points. The implication is that the fixed rate is 45 basis points greater than the yield on a security having the same maturity.

Such a rate schedule, which is typically provided by a professional swap dealer, may be interpreted as follows. A swap dealer will give a two-way quote in which the bid is the fixed rate at which he is willing to do a swap that requires him to pay the fixed rate. The ask represents the rate at which he will do a swap that requires him to receive the fixed rate. The spread must be positive.

Determining the Swap Rate

Let us reconsider the coupon swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax. The swap rate was arbitrarily assumed to be 6.40 percent. We will demonstrate how this rate will be set.

Table 10.4 Bid–Ask Quotes for Euro-Denominated IRS

To understand the pricing of swaps, consider an alternative financial arrangement in which Bank Exotica issues a fixed-rate bond with a principal of US$2,500,000 and uses the proceeds to acquire a floating-rate bond with the same principal. Assume that the benchmark for the floating-rate bond is the six-month LIBOR and that both bonds pay coupons on a semiannual basis. The initial cash flow is zero because the proceeds of the fixed-rate issue will be just adequate to purchase the floating-rate security. Every six months the bank will receive a floating rate of interest based on the six-month LIBOR on a principal amount of US$2,500,000 and will have to make an interest payment for the same principal, based on a fixed rate of interest. When the two bonds mature, the amount received when the bank redeems the principal on the floating-rate bond held by it will be just adequate for it to repay the principal on the bond it issued. The net cash flow at maturity is therefore zero. Structurally this financial arrangement corresponds to an interest-rate swap with a notional principal of US$2.5 million in which the bank pays a fixed rate of interest every six months in return for an interest stream that is based on the six-month LIBOR. To ensure that the combination of the two bonds exactly matches the structure of the swap, we need to assume that the bonds also pay coupons based on the same day-count convention, which in this case has been assumed to be 30/360.

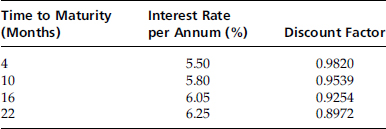

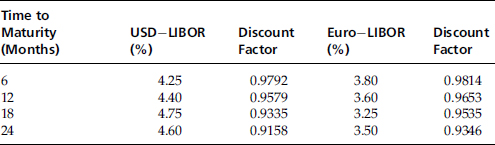

We will demonstrate how to determine the fixed rate of a coupon swap. Let us assume that the term structure for LIBOR is as shown in Table 10.5.

Table 10.5 Observed Term Structure

| Time to Maturity (Months) | Interest Rate Per Annum (%) |

| 6 | 5.25 |

| 12 | 5.40 |

| 18 | 5.75 |

| 24 | 6.00 |

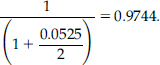

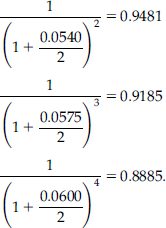

These interest rates need to be converted to discount factors, which can be done as follows.2 The discount factor for the first payment (after six months) is

The remaining discount factors may be computed as follows:

Because we are at the start of a coupon period, the price of the floating-rate bond should be equal to the principal value of US$2,500,000. Therefore, the question is, what is the coupon rate that will make the fixed-rate bond also have the same value at the outset? Let us denote the annual coupon in dollars by C.

We require that

This implies that the coupon rate is

![]()

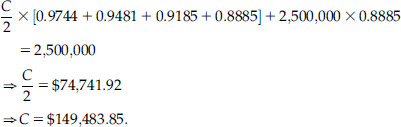

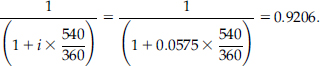

The Market Method

The convention in the LIBOR market is that if the number of days for which the rate is quoted is N, then the corresponding discount factor is given by

Table 10.6 Discount Factors per Market Convention

| Time to Maturity (Months) | Discount Factor |

| 6 | 0.9744 |

| 12 | 0.9488 |

| 18 | 0.9206 |

| 24 | 0.8929 |

Consider the 18-month rate of 5.75 percent. The corresponding discount factor is

The vector of discount factors for our example is shown in Table 10.6. The corresponding swap rate is 5.7323 percent.

Valuation of a Swap During Its Life

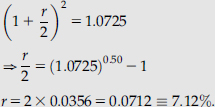

Let us consider the swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax. Assume that two months have elapsed since the swap was entered into and that the current term structure of interest rates is as given in Table 10.7. We have used the market method to compute the discount factors.

Table 10.7 The Term Structure of Interest Rate after Two Months

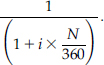

The value of the fixed-rate bond can be obtained using the following equation:

The value of the floating-rate bond may be computed as follows. The next coupon known for it would have been set at time zero—that is two months before the date of valuation. The magnitude of this coupon is

![]()

Once this coupon is paid, the value of the bond will revert back to its face value of 2,500,000. The value of this bond after four months will be $2,565,625. Its value today is:

![]()

From the standpoint of the fixed-rate payer, the swap is equivalent to a long position in a floating-rate bond that is combined with a short position in a fixed-rate bond. The value of the swap for the fixed-rate payer is

![]()

In other words, because the value of the fixed-rate liability is higher than that of the floating-rate asset, the value of the swap for Bank Exotica, the fixed-rate payer, is negative. This implies that if the bank seeks a cancellation of the original swap, then it will have to pay $4,466 to the counterparty. This transaction can only take place with the consent of the counterparty, of course.

From the standpoint of the counterparty, the value of the swap is $4,466. In the event of cancellation of the contract, it will get a cash flow of this magnitude from Bank Exotica.

Terminating a Swap

As we have just seen, one way to exit from an existing swap contract is to have it cancelled with the approval of the counterparty. This will entail an inflow or outflow of the value of the swap, depending on how interest rates have moved, after the last periodic cash flow was exchanged. In market parlance, this is known as a buyback or closeout. In our illustration, Bank Exotica would have to pay $4,466 to Bank Halifax to close out the contract. Bank Exotica will have the option of selling the swap to a party other than Bank Halifax, the original counterparty. This would, of course, require the approval of Bank Halifax. In this case as well, the party who buys the swap from the bank will expect to be paid the value of the swap, which is $4,466 in this case.

Another way for Bank Exotica to exit from its commitment would be to do an opposite swap with a third party. It would have to do a 22-month swap with a party in which it pays LIBOR and receives the fixed rate. This is known as a reversal.

Remember: if it were to do so, two swaps would exist. So Bank Exotica would be exposed to credit risk from the standpoint of both counterparties.

The Role of Banks in the Swap Market

In the early years, when the swap market was evolving, it was a standard practice for banks to play the role of an intermediary. They would bring together two counterparties in return for what was termed an arrangement fee. As the market has evolved, such arrangement fees have become extremely rare except perhaps for contracts that are very exotic or unusual.

These days, most banks will don the mantle of a principal. The reasons why they are required to do so are twofold. First, nonbank counterparties are reluctant to reveal their identity when entering into such deals, so they are more comfortable dealing with a bank while negotiating. Second, for most parties to such transactions, it is easier to evaluate the credit risk while dealing with a bank than while negotiating with a nonbank counterparty. And, as we have seen, swaps being OTC transactions always carry an element of counterparty risk.

In the days when the market was in its infancy, banks would primarily do reversals. They would do a fixed–floating deal with a party only if they were hopeful of immediately concluding a floating fixed deal for the same tenor with a third party. Parties that carry equal and offsetting swaps in their books are said to be running a matched book. As we saw earlier, such parties are exposed to default risk from both counterparties. These days, banks are less finicky about maintaining such a matched position, and in most cases they are willing to take on the inherent exposure for the period until they can eventually locate a party for an offsetting transaction.

Motivation for the Swap

A party to a swap may enter into the contract with a speculative motive or with an incentive to hedge. In addition, such transactions may also be used to undertake what is known as credit arbitrage arising from the comparative advantage enjoyed by the participating institutions. We will analyze each potential use.

Speculation

Morgan Bank and Brown Brothers Bank are both players in the U.S. capital market, but they have different expectations as to where interest rates are headed. Morgan speculates that rates are likely to steadily decline over the next two years, whereas Brown Brothers expects rates to rise steadily over the same period. Assume they enter into a coupon swap with a tenor of two years in which Morgan agrees to pay interest at LIBOR every three months on a notional principal of $100 million, and Brown Brothers agrees to pay interest on the same notional principal and with the same frequency but at a fixed rate of z percent per annum.

Both parties are speculating on the interest rate. If Morgan is right and rates do decline as it anticipates, then its floating-rate payments are likely to be lower than its fixed-rate receipts, thereby leading to net cash inflows for it. But if Brown Brothers is correct and rates rise steadily as it anticipates, its floating-rate receipts are likely to be in excess of its fixed-rate payments, thereby leading to net cash inflows for it. Because both parties are speculating, ex post one will stand vindicated and the other will have to countenance a loss.

Hedging

Swaps can be used as a hedge against anticipated interest-rate movements. Donutz a company based in Detroit, has taken a loan from First National Bank at a rate of LIBOR + 75 basis points (bp). The company is worried that rates are going to increase and seeks to hedge by converting its liability into an effective fixed-rate loan. One way to do so would be to renegotiate the loan and have it converted to a loan carrying a fixed rate of interest. This may not be easy in real life, however. There will be a lot of administrative and legal issues and related costs. It may be easier for the company to negotiate a coupon swap in which it pays fixed and receives LIBOR.

Assume that Morgan Bank agrees to enter into a swap with Donutz, paying LIBOR in return for a fixed interest stream based on a rate of 5.75 percent per annum.

The net result from the standpoint of Donutz may be analyzed as follows:

- Outflow 1 (interest on the original loan): LIBOR + 75 bp

- Inflow 1 (receipt from Morgan Bank): LIBOR

- Outflow 2 (payment to Morgan Bank): 5.75 percent

- Net outflow: 5.75% + 0.75% = 6.50% per annum.

The company has converted its loan to an effective fixed-rate liability carrying interest at the rate of 6.50 percent per annum.

Comparative Advantage and Credit Arbitrage

At times there are situations in which a party, despite being at a disadvantage from the standpoint of interest payments with respect to another party in both fixed-rate and variable-rate debt markets, may enjoy a comparative advantage in one of the two.

Assume that Infosys, a software company based in San Jose, can borrow at a fixed rate of 7.50 percent per annum and at a variable rate of LIBOR + 125 bp. IBM is in a position to borrow at a fixed rate of 6 percent per annum and a variable rate of LIBOR + 60 bp. Infosys has to pay 150 bp more as compared to IBM if it borrows at a fixed rate but only 65 basis points more if it borrows at a floating rate. We say that although IBM enjoys an absolute advantage from the standpoint of borrowing in terms of both fixed-rate and floating-rate debt, Infosys has a comparative advantage if it borrows on a floating-rate basis.

Assume that Infosys wants to borrow at a fixed rate while IBM would like to borrow at a floating rate. It can be demonstrated that an interest-rate swap can be used to lower the effective borrowing costs for both parties compared to what they would have had to pay in its absence.

Let us assume that IBM borrows $10 million at a fixed rate of 6 percent per annum, and Infosys borrows the same amount at LIBOR + 125 bp. The two parties can then enter into a swap in which Infosys agrees to pay interest on a notional principal of $10 million at the rate of 5.75 percent per annum in exchange for a payment based on LIBOR from IBM. The effective interest rate for the two parties may be computed as follows:

- IBM: 6% + LIBOR − 5:75% = LIBOR + 25 bp

- Infosys: LIBOR + 125 bp + 5:75% − LIBOR = 7:00%

IBM has a saving of 35 basis points on the floating-rate debt, and Infosys has a saving of 50 bp on the fixed-rate debt. What exactly does this cumulative saving of 85 basis points represent? IBM has an advantage of 1.50 percent in the market for fixed-rate debt and 65 bp in the market for floating-rate debt. The difference of 85 basis points manifests itself as the savings for both parties considered together.

Let us introduce a bank into the picture. Assume that IBM borrows at a rate of 6 percent per annum and enters into a swap with First National Bank in which it must pay LIBOR in return for a fixed-rate stream based on a rate of 5.65 percent. Infosys, on the other hand, borrows at LIBOR + 125 bp and enters into a swap with the same bank, receiving LIBOR in return for payment of 5.85 percent.

The net result of the transaction may be summarized as follows:

- IBM: Effective interest paid = 6% + LIBOR − 5.65% = LIBOR + 35 bp

- Infosys: Effective interest paid = LIBOR + 125 bp + 5.85% − LIBOR = 7.10%

- First National Bank: Profit from the transaction = LIBOR − 5.65% − LIBOR + 5.85% = 20 bp.

The difference in this case is that the comparative advantage of 85 basis points has been split three ways. IBM saves 25 basis points, Infosys saves 40 basis points, and the bank makes a profit of 20 basis points.

We must point out that the transaction that entails a role for the bank is more realistic than a deal in which the two companies identify and directly enter into a swap with each other.

Swap Quotations

The swap rate in the market can be quoted in four different ways.3 First, there are two possibilities with respect to the interest payments: they may be on either an annual basis or a semiannual basis. Second, payments may be settled either on a bond market or on a money market basis, the difference being that the first convention is based on a 365-day year and an actual/365 day-count convention, whereas the second is based on a 360-day year and an actual/360 day count convention.

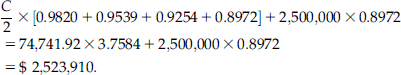

Quotes on a semiannual basis can be converted to equivalent values on an annual basis and vice versa. Example 10.4 illustrates the required procedures.

The fixed rate for a swap is given as 7.25 percent per annum payable semiannually. To convert this to the corresponding value for an annual pay basis, we need to find the effective annual rate. This is given by

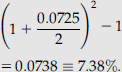

Consider a situation in which the fixed rate is quoted as 7.25 percent per annum payable annually. To convert this to an equivalent rate for a semiannual pay basis, we need to find the nominal annual rate that will yield 7.25 percent on an effective annual basis if compounding is undertaken semiannually.

This may be calculated as

The fixed rates payable are quoted on a bond basis, whereas floating rates are quoted on a money market basis. To convert from a bond basis to a money market basis, we have to multiply the quote by 360/365; if we seek to do the reverse, we multiply by 365/360.

Matched Payments

Numero Uno Corporation has issued bonds carrying a coupon of 6.25 percent per annum. It is of the opinion that market rates could decline, so it wishes to undertake a swap in which it has to pay floating and receive fixed. Assume that the bonds pay interest on a semiannual basis and that the swap also entails a six-month exchange of cash flows. The principal of the bonds is assumed to be $10 million, as is the notional principal of the swap.

We will assume that Bank Deux is willing to arrange a swap that is suitable for Numero Uno but with a swap rate of 5.80 percent per annum. However, the company wants a fixed payment of $312,500 to match the cash outflow on account of the bonds it issued. Bank Deux would accommodate the request as follows. Because Numero Uno wants to receive a higher fixed payment compared to what it would ordinarily have received, it must compensate it in the form of a positive spread with respect to the floating-rate payment that it is required to make. In this case, the difference in the fixed-rate payments is $45,000 per annum, which corresponds to 45 basis points. So the bank will require Numero Uno to make a payment based on a rate of LIBOR + 45 basis points while making the floating counterpayment every six months.

Currency Swaps

A currency swap is like an interest-rate swap in the sense that it requires two counterparties to commit themselves to the exchange of cash flows at prespecified intervals. The difference in this case is that the two cash-flow streams are denominated in two different currencies. The two counter-parties also agree to exchange, at the end of the stated time period or the maturity date of the swap, the corresponding principal amounts computed at an exchange rate that is fixed right at the outset.4

As mentioned earlier, because the counterpayments are denominated in two different currencies, there are three possibilities from the standpoint of interest computation. In other words, these swaps may be on any of the following bases:

- Fixed rate–fixed rate;

- Fixed rate–floating rate;

- Floating rate–floating rate.

A currency swap always requires an exchange of principal at the time of maturity. However, there do exist contracts that entail an exchange of principal twice: at inception as well as at maturity. Such swaps are referred to as cash swaps.

We will assume that the swap described in the preceding illustration is a cash swap. Such a contract will typically entail the following transactions:

- Bank Atlantic will borrow US$7.5 million in New York.

- Bank Europeana will borrow €6 million in Frankfurt.

- Bank Atlantic will transfer the dollars to Bank Europeana in exchange for the equivalent payment denominated in euros.

- On the maturity date of the swap, the principal amounts will be swapped back. In most cases, the terminal exchange is based on the exchange rate that was prevailing at the outset—in other words, the same exchange rate that was used to compute the initial exchange of principal. In our illustration, therefore, we will assume that Bank Atlantic will make a payment of €6 million to Bank Europeana after two years in exchange for a cash flow of US$7.5 million. Such a swap in which the same amount of principal is exchanged is known as a par swap.5

- At the end of two years, Bank Atlantic would use the dollars received by it to repay the U.S. dollar–denominated loan that it had taken two years prior.

- Bank Europeana would use the euros received by it to repay the loan that it had taken in Frankfurt two years earlier.

As given in Example 10.5, a swap transaction such as this enables each party to service the debt of the counterparty. Bank Atlantic has taken a dollar-denominated loan. It will service it using the dollar-denominated payments that it receives every six months from Bank Europeana. Similarly, Bank Europeana has taken a euro-denominated loan that it will service using the euro-denominated payments it periodically receives from Bank Atlantic.

Bank Atlantic and Bank Europeana agree to execute a contract in which they will exchange cash flows denominated in U.S. dollars and the euro over two years. Per the terms of the agreement, Bank Atlantic will make a payment at the end of every six months denominated in euros and at an interest rate of 4.25 percent per annum. The payments will be based on a principal amount of €6 million. Bank Europeana, on the other hand, will make payments at the same frequency but denominated in dollars and with an interest rate of 5.40 percent per annum. These payments will be based on a principal of US$7.5 million.

At the end of the two-year period, Bank Atlantic will pay €6 million to Bank Europeana, which in turn will make a counterpayment of US$7.5 million. The implicit exchange rate of 0.8000 USD–EUR is fixed right at the outset and is typically the spot rate of exchange prevailing in the currency market at that point in time.

Cross-Currency Swaps

Technically speaking, the term currency swap is applicable only for transactions that entail the exchange of cash flows computed on a fixed rate–fixed rate basis, such as the deal that we have just studied. Currency swaps in which one or both payments are based on a floating rate of interest should, strictly speaking, be termed cross-currency swaps. Within cross-currency swaps we make a distinction between coupon swaps, which are on a fixed rate–floating rate basis, and basis swaps, which are on a floating rate–floating rate basis.

Valuation

We will explore the mechanics of currency-swap valuation by focusing on the swap between Bank Atlantic and Bank Europeana. The swap may be viewed as a combination of the following transactions. Assume that Bank Atlantic has issued a fixed-rate bond in euros with a principal of €6 million and converted the proceeds to dollars at the spot rate of 0.8000 USD–EUR. The proceeds in dollars can be perceived as having been invested in fixed-rate bonds denominated in dollars. From the perspective of the counterparty, the transaction may be perceived as follows. Assume that Bank Europeana has issued fixed-rate, dollar-denominated bonds with a face value of US$7.5 million, converted the proceeds to euros at the prevailing spot rate, and invested the equivalent in euros in fixed-rate bonds in that currency. Every six months Bank Atlantic will receive interest in dollars and pay interest in euros, and Bank Europeana will pay interest in dollars and receive interest in euros. So a currency swap between two parties is equivalent to a combination of transactions in which each party issues a bond in one currency to the other, and uses the proceeds to acquire a bond issued by the counterparty. The fixed rate that is applicable in either currency is the coupon rate associated with a par bond in that currency, as we have seen in the case of fixed–floating interest-rate swaps. However, because two currencies are involved, we need the term structure of interest rates for both currencies.

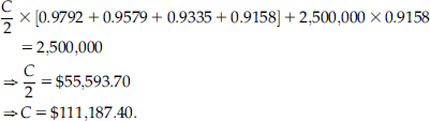

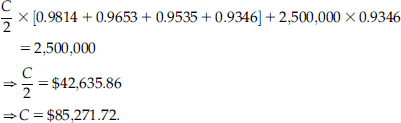

Table 10.8 Term Structure for U.S. Dollars and the Euro

Consider the data given in Table 10.8.

The value of the fixed rate for U.S. dollar may be determined as follows. Consider a bond with a face value of US$2.5 million. The coupon for a par bond denominated in U.S. dollar is given by

This corresponds to a rate of 4.4475 percent per annum.

Similarly we can compute the coupon for a bond denominated in euros

This corresponds to a coupon of 3.4109 percent per annum.

If the swap had been such that the rate for dollars was fixed while that for the payment in euros was variable, then the applicable rate would be 4.4475 percent for the dollar-denominated payments and LIBOR for the counterpayments. On the other hand, if the rate is fixed for the payments in euros and is variable for the dollar-denominated payments, then the applicable rate is LIBOR for the payment in dollars and 3.4109 for the payments in euros. Finally, if payments in both currencies are on a floating-rate basis, then it is LIBOR for LIBOR.

Currency Risks

A currency swap, as we would expect, exposes both parties to currency risk. Let us consider the swap in which Bank Atlantic borrows and makes a payment of US$7.5 million to Bank Europeana in return for a counter-payment of €6 million. The exchange rate for the cash-flow swap was 0.8000 USD–EUR.

At maturity, Bank Europeana would pay back US$7.5 million to the U.S. bank and receive €6 million in return. Assume that in the intervening three years the dollar has appreciated to 0.8125 USD–EUR. Bank Atlantic would benefit by the fact that the terminal exchange of principal is based on the original exchange rate of 0.8000 USD–EUR. Because, if €6 million are converted at the prevailing rate of 0.8125 USD–EUR, it stands to receive only US$7,384,615. Therefore, the counterparty that is slated to receive the currency that has appreciated during the life of the swap stands to gain from the fact that the terminal exchange of principal is based on the exchange rate prevailing at the outset, whereas the other party stands to lose. In our illustration, Bank Atlantic avoids a loss of US$115,385, and Bank Europeana forgos an opportunity to save an identical amount.

Hedging with Currency Swaps

A swap can be used as a mechanism for hedging foreign-currency exposure. Telekurs, a telecom company based in Frankfurt, has issued a Yankee bond for US$25 million, carrying interest at the rate of 6 percent per annum payable semiannually. The bonds have four years to maturity, and the company seeks to hedge its exposure to the U.S. dollar–euro exchange rate, because all its income is primarily denominated in euros. Assume that the current exchange rate is 0.8000 USD–EUR.

The company can use a swap to hedge its currency exposure. Because it has a payable in U.S. dollars, it needs a contract in which it will receive cash flows in dollars and make payments in euros. If the company is of the opinion that rates in the euro zone are likely to rise, then it can negotiate a swap in which it makes a fixed rate–based payment in euros to a counterparty in exchange for a fixed rate–based income stream in dollars. The dollar inflows should be structured to match the company's projected outflows in that currency. This will lead to a situation in which its exposure to the dollar is perfectly hedged.

Endnotes

1. In some swap markets, the fixed-rate payer is termed the buyer and the counterparty is termed the receiver.

2. The discount factor for a given maturity is the present value of a dollar to be received at the end of the stated period.