CHAPTER 1

An Introduction to Financial Institutions, Instruments, and Markets

The Role of an Economic System

Economic systems are designed to collect savings in an economy and allocate the available resources efficiently to those who either seek funds for current consumption in excess of what their resources would permit or to invest in productive assets.

The key role of an economic system is to ensure efficient allocation. The efficient and free flow of resources from one economic entity to another is a sine qua non for a modern economy. This is because the larger the flow of resources and the more efficient their allocation, the greater the chance that the requirements of all economic agents can be satisfied, and consequently the greater the odds that the output of the economy as a whole will be maximized.

The functioning of an economic system entails the making of decisions about both the production of goods and services and their subsequent distribution. The success of an economy is gauged by the extent of wealth creation. A successful economy is one that makes and implements judicious economic decisions from the standpoints of both production and distribution. In an efficient economy, resources will be allocated to those economic agents who are in a position to derive the optimal value of output by employing the resources allocated to them.

Why are we giving the efficiency of an economic system so much importance? Because every economy is characterized by a relative scarcity of resources as compared to the demand for them. In principle, the demand for resources by economic agents can be virtually unlimited, but in practice economies are characterized by a finite stock of resources. Efficient allocation requires an extraordinary amount of information as to what people need, how goods and services can best be produced to cater to these needs, and how the produced output can best be distributed.

Economic systems may be classified as either command economies or free-market economies. These are the two extreme ends of the economic spectrum. Most modern economies tend to display characteristics of both kinds of systems, and they differ only with respect to the level of government control.

A Command Economy

In a command economy, like that of the former Soviet Union, all production and allocation decisions are made by a central planning authority. The planning authority is expected to estimate the resource requirements of various economic agents and then rank them in order of priority in relevance to social needs. Production plans and resource-allocation decisions are then made to ensure that resources are directed to users in descending order of need. Communist and socialist systems that were based on this economic model ensured that citizens complied with the directives of the state by imposing stifling legal and occasionally coercive measures.

The failure of the command economies was inherent in their structure. As mentioned, efficient economic systems need to aggregate and process an enormous amount of information. Entrusting this task to a central planning authority proves infeasible and also means the quality of information is substandard. The central planning authority was supposed to be omniscient and was expected to have perfect information about available resources and the relative requirements of the socioeconomic system. This was necessary for the authority to ensure that optimal decisions were made about production and distribution.

Command economies were plagued by blatant political interference. The planning authority was often prevented from making optimal decisions because of political pressures. The system gave enormous power to planners that permeated all facets of the social system and not just the economy. One hallmark of such a system was the absence of pragmatism and the presence of a naïve idealism that was out of touch with reality. Planners used their authority to devise and impose stifling rules and regulations. The regulations, which were in principle intended to ensure optimal decision making, at times went to the ridiculous extent of imposing penalties on producers whose output exceeded what was allowed by the permit or license given to them.

Such economies were a colossal failure, characterized by an output that was invariably far less than the ambitious targets that were set at the outset of each financial year. When confronted with the specter of failure, planners tended to place the blame on those who were responsible for implementing the plans. The bureaucrats in charge of implementation passed the buck upward by alleging improper decision making on the part of the planners. Eventually, contradictions in the system led to either the total repeal of such systems or to substantial structural changes that brought in key features of a market economy.

A Market Economy

In principle, a market economy works as follows. Economic agents are expected to make the most profitable use of the resources at their disposal. What is profit? Profit is defined as the revenues from sales minus the costs of production of the goods sold. Profit is a function of the prices of the inputs or the factors of production—such as land, labor, and capital—and the prices of the output. An optimal economic decision is defined as one that maximizes profit. Economic agents who generate surpluses of income in excess of expenditures will be able to attract more and better resources. Failure, as manifested by sustained losses, will result in those economic agents being denied access to the resources they seek.

In such a system, the prices of both inputs and outputs are determined by factors of supply and demand. In contrast to a command economy, a market economy is characterized by decentralized decision making. In principle, every agent is expected to take a rational decision by evaluating competing resource needs based on his or her ability to generate surpluses. Every decision maker will have a required rate of return on investment. The threshold return, or the return above which the venture will be deemed profitable, is the cost of capital for the decision maker. A project is considered to be worth the investment only if its expected rate of return is greater than the cost of the capital being invested.

As we can surmise, the key decision variables in these economies are the prices of inputs and outputs. For such economies to work in an optimal fashion, prices must accurately convey the value of a good or a service from the standpoints of both producers who employ factors of production and consumers who consume the end products. The informational accuracy of prices results in the efficient allocation of resources for the following reasons. If the inputs for the production process such as labor and capital are accurately priced, then producers can make optimal production-related decisions. Similarly, if the consumers of goods and services perceive their prices to be accurate, they will make optimal consumption decisions. The accuracy of input-related costs and output prices will be manifest in the form of profit maximization, which is the primary motivating factor for agents in such economies to engage in economic enterprise.

How do such systems ensure that prices of inputs and outputs are informationally accurate? This is ensured by allowing economic agents to trade in markets for goods and services. If agents have the perception that the price of an asset is different from the value that they place on it, they will seek to trade. If the prevailing price is lower than the perceived value, buyers will seek to buy more of the good than the quantity on offer. If so, the market price will be bid up because of demand being greater than the amount on offer. This demand–supply disequilibrium will persist until the price reaches the optimal level. Similarly, if the price of the good is perceived to be too high relative to the value placed on it by agents, sellers will seek to offload more than what is being demanded. Once again, the supply–demand imbalance will cause prices to decline until equilibrium is restored. Differing perceptions of value will manifest themselves as supply–demand imbalances, the process of resolution of which ultimately helps to ensure that the prices of assets accurately reflect their value.

Opinion

Although free-market economies have largely been more successful than command economies, no one would advocate a total absence of a government's role in economic decision making. Unfettered capitalism, particularly in the aftermath of the current economic crisis, is unlikely to find acceptance anywhere. There are disadvantaged sections of every society whose fate cannot be left to the market and whose well-being has to be ensured by policy makers to promote overall welfare.

Classification of Economic Units

Economic agents are usually divided into three categories or sectors: government, business, and household.

The government sector consists of a nation's central or federal government, state or provincial governments, and local governments or municipalities. The business sector consists of sole proprietorships, partnerships, and both private and public limited companies. Sometimes business units are broadly subclassified as financial corporations and nonfinancial corporations.

Proprietorships

A proprietorship, also known as a sole proprietorship, is a business owned by a single person and is the easiest way to start a business. An owner may do business in his or her own name or using a trade name. For instance, a consultant named John Smith may run the business in his name or choose a name such as Business Systems. The owner is fully responsible for all debts and obligations of the business. In other words, creditors—entities to which the business owes money—may stake a claim against all assets of the proprietor, whether they are business-related assets or personal assets. In legal parlance, this is referred to as unlimited liability, as opposed to a corporation whose owners have limited liability, a point we will shortly explore in greater detail.

The start-up costs of a sole proprietorship are usually fairly low compared to other forms of business. However, unlike a corporation, such businesses face relative difficulties in raising additional capital if and when they choose to expand the scope of their operations. Usually, in addition to the owner's personal investment, the only source of funds is a loan from a commercial bank.

Legally, the proprietorship is an extension of the owner. The owner is permitted to employ other people. The net profits from the business are clubbed with the proprietor's other income, if any, for the purpose of taxation. The life span of these entities is fairly uncertain. If the owner dies, the business ceases to exist.

Partnerships

A partnership is a business entity owned by at least two people or partners. One partner may be a corporation, a concept that we will explain next. The legal extension of the partnership is an extension of the partners. Like a proprietorship, a partnership is allowed to employ others, and it can conduct a business under a trade name. Two lawyers named Joan Smith and Mary Jones may conduct their business as Smith & Jones or under a trade name such as Legal Point. In a general partnership, the partners have unlimited liability and a partner is personally responsible not only for her own acts but also for the actions of her other partners as well as employees.

There are two categories of partnerships in many countries: general partnerships and limited partnerships. A general partnership is what we have just discussed. In a limited partnership, there are two categories of partners, namely general partners and limited partners. The general partners are usually a corporation and have management control. They are characterized by unlimited liability. The limited partners, on the other hand, are like shareholders in a corporation: their potential loss is limited to the investment they have made.

Like a sole proprietorship, a partnership is also fairly easy to establish. However, unlike a proprietor, who is the sole decision maker, partners must share authority with the others. It is very important to draw up a partnership agreement at the outset, where issues such as profit sharing are clearly spelled out. Compared to corporations, partnerships also find it relatively difficult to raise capital in order to expand their businesses.

Corporations

A corporation or a limited company is a legal entity that is distinct and separate from its owners, who are referred to as shareholders or stockholders. A corporation may and usually will have multiple owners as well as a number of employees on its payroll. It must necessarily do business under a given trade name. Because a corporation is a separate legal entity, it has the right to sue and be sued in its own name. Shareholders of a corporation enjoy limited liability. Unlike a proprietorship or partnership, the ownership of a company can easily change hands. Each shareholder will possess a number of shares of the company that can be usually bought and sold in a marketplace known as a stock exchange. Although such share transfers may result in one party relinquishing majority control in favor of another, the transfers per se have no implications for the corporation's continued existence or its operations. Unlike proprietorships and partnerships, corporations find it relatively easier to raise both debt or borrowed capital, as well as equity or owners' capital. However, in most countries corporations are extensively regulated and are required by statutes to maintain extensive records pertaining to their operations. The cost of incorporation and the costs of raising equity through share issues can also be substantial. Although owners of a corporation may be a part of its management team, very often ownership and management are segregated, entrusting the management of day-to-day activities to a team of professional managers. In some countries, there exist entities known as private limited companies. These companies cannot offer shares to the general public, and the shares cannot be traded on a stock exchange. However, the shareholders continue to enjoy limited liability, hence the name. The disclosure norms for public limited companies are generally more stringent than those for private limited companies.

During a given financial year, every economic unit, irrespective of which sector it may belong to, will get some form of income in the course of its operations and will also incur expenditure in some form. Depending on the relationship between the income earned and the expenditure incurred, an economic unit may be classified into one of the following three categories: (1) a balanced budget unit, (2) a surplus budget unit, or (3) a deficit budget unit.

In reality, a balanced budget unit is impossible, so it exists only in the realm of textbooks. It is virtually impossible for a business or government to ensure that its scheduled income during a period is perfectly matched with its scheduled expenditure during the same period. An economic unit may be a surplus budget unit (SBU) or a deficit budget unit (DBU). A surplus budget unit is one with an income that exceeds its expenditure, whereas a deficit unit is one with expenses that exceed its income. Usually, in most countries, governments and businesses invariably tend to be deficit budget units, whereas households consisting of individuals and families generally tend to be savers—that is, they tend to have budget surpluses. By this we do not mean that all households and individuals are savers or that all governments and businesses have a budget deficit. We mean that even though it is not uncommon for a government or a business to have a surplus in a given financial period, as a group the government and business sectors generally tend to be net borrowers. By the same logic, it is not necessary that all households should save, although the category as a whole generally has a budget surplus in most periods. Finally, a country as a whole may have a budget surplus or a budget deficit.

An Economy's Relationship with the External World

The record of all economic transactions between a country and the rest of the world (ROW) is known as its balance of payments (BOP). It is a record of a country's trade in goods, services, and financial assets with the rest of the world. In other words, it is a record of all economic transactions between a country and the outside world. The transaction may be a requited transfer of economic value or an unrequited transfer of economic value. In this context, the term requited connotes that the transferor receives a compensation of economic value from the transferee. On the other hand, an unrequited transfer represents a unilateral gift made by the transferor.

The BOP is typically broken into three major categories of accounts, each of which is further subdivided into various components. The major categories are as follows:

- The current account: This accounting head includes imports and exports of goods and services, as well as earnings on investments.

- The capital account: Under this heading we have transactions that lead to changes in a country's foreign assets and liabilities.

- The reserve account: This account is similar to the capital account, in the sense that it also deals with financial assets and liabilities, but it deals only with reserve assets—that is, those assets used to settle the deficits and surpluses that arise on account of the other two categories taken together.

A reserve asset is one that is acceptable as a means of payment in international transactions and that is held by and exchanged between the monetary authorities of various countries. It consists of monetary gold, assets denominated in foreign currencies, special drawing rights (SDRs), and reserve positions at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). If there is a deficit in the current and capital accounts taken together, then there will be a depletion of reserves. However, if the two accounts show a surplus when taken together, there will be an increase in the level of reserves.

The balance of payments is an accounting system that is based on the double-entry system of bookkeeping. Every transaction is recorded on both the sides—that is, as both a credit and a debit. All transactions that have led or will lead to an inflow of payments into the country from the ROW will be shown as credits. The payments themselves would be depicted as the corresponding debits. Similarly, all transactions that have led to or will lead to a flow of payments from the country to the ROW will be recorded as debits. The payments will be recorded as the corresponding credits.

A payment received from abroad will increase the country's foreign assets. Thus, an increase in foreign assets or a decrease in foreign liabilities will be shown as a debit. On the other hand, a payment made to an external party will either reduce the country's holding of foreign assets or show up as an increase in its liabilities. This will be shown as a credit.

The accounting principle may also be viewed as follows. Any transaction that leads to an increase in the demand for foreign exchange should be shown as a debit, and any transaction that leads to an increase in the supply of foreign exchange should be shown as a credit. Capital outflows will be debited, whereas capital inflows will be credited.

The balance of payments must always balance. A current account deficit must be matched by a surplus in the capital account or by a depletion of reserves or both. A surplus in the capital account would indicate that the country's foreign liabilities have gone up—in other words, the country has borrowed from abroad. While analyzing the BOP, it is customary to study several subcategories of accounts. We will look at two of the most important subclassifications.

The Balance of Trade

The balance of trade is equal to the sum total of merchandise exports and imports. It consists of all raw materials and manufactured goods bought, sold, or given away. If it shows a surplus, it indicates that exports of goods from the country exceed imports into it; if it shows a deficit, it would indicate that imports exceed exports. The balance of trade is a politically sensitive statistic. If a country's balance of trade shows a deficit, then industries that are being hurt by competition from abroad will typically raise a hue and cry about the need for a level playing field in order to take on the foreign competition.

The Current Account Balance

The current account balance refers to the sum total of the following accounts:

- Exports of goods, services, and income;

- Imports of goods, services, and income; and

- Net unilateral transfers.

Services include tourism, transportation, engineering, and business services. Fees from patents and copyrights are also recognized under this category. Income includes revenue from financial assets, such as dividends from shares and interest from debt securities. Unilateral transfers are one-way transfers of assets, such as worker remittances from foreign countries, and direct foreign aid.

A current account that shows a deficit indicates that the country's liabilities have increased; if it shows a surplus, it means that a country's assets held abroad have increased.

Financial Assets

“A financial asset is a claim against the income or wealth of a business firm, a household, or a government agency, which is represented usually by a certificate, a receipt, a computer record file, or another legal document, and is usually created by or is related to the lending of money.”1

A financial claim is born in the following fashion. Whenever funds are transferred from a surplus budget unit to a deficit budget unit, the DBU will issue a financial claim. It signifies that the party that is transferring the funds has a claim against the party that is accepting the funds. The transfer of funds from the lender may be in the form of a loan to the borrower or constitute the assumption of an ownership stake in the venture of the borrower. In the case of loans, the claim constitutes a promise to pay the interest either at maturity or at periodic intervals and to repay the principal at maturity. Such claims are referred to as debt securities or as fixed income securities. In the case of fund transfers characterized by the assumption of ownership stakes, the claims are known as equity shares. Unlike debt securities, which represent an obligation on the part of the borrower, equity shares represent a right to the profits of the issuing firm during its operation and to such assets that may remain after all creditors are fully paid as in the event of the venture's liquidation. Remember that claims are always issued by the party that is raising funds, and they are held by parties that are providing the funds.

To the issuer of the claim, the claim is a liability because it signifies that it owes money to another party. To the lender, or the holder of the claim, it is an asset because it signifies that the holder owns an item of value. The sum total of financial claims issued must equal the total financial assets held by investors, and every liability incurred by a party must be an asset for another investor.

Why do investors acquire financial assets? Financial assets are essentially sought after for three reasons.

- They serve as a store of value or purchasing power.

- They promise future returns to their owners.

- They are fungible—that is, they can be easily converted into other assets and vice versa.

In addition to debt securities and equity shares, we will also focus on the following assets: money, preferred shares, foreign exchange, derivatives, and mortgages and mortgage-backed securities.

Money

Money is a financial asset because all forms in use today are claims against some institution. Contrary to popular perception, money is not just the coins and currency notes that are handled by economic agents. One of the largest components of money supply today is the checking account balances held by depositors with commercial banks. From the banks' standpoint, these accounts represent a debt obligation. Banks have the capacity to both expand and contract the money supply in an economy. Currency notes and coins also represent a debt obligation of the central bank of the issuing country, such as the Federal Reserve in the United States. In today's electronic age, newer forms of money have emerged, such as credit cards, debit cards, and smart cards.

Money performs a wide variety of important functions, and for that reason it is much sought after. In a modern economy, all financial assets are valued in terms of money, and all flows of funds between lenders and borrowers occur via the medium of money.

Money as a Unit of Account or a Standard of Value

In the modern economy, the value of every good and service is denominated in terms of the unit of currency. Without money, the price of every good or service would have to be expressed in terms of every other good or service. The availability of money leads to a tremendous reduction in the amount of price-related information that has to be processed.

Take the case of a 100 good economy. In the absence of money we would require 100C2 or 4,950 prices.2 However, if a currency were to be available, we would require only 100 prices, a saving of almost 98 percent in terms of the required amount of information.

Money as a Medium of Exchange

Money is usually the only financial asset that every business, household, and government department will accept as payment in return for goods and services.

Why is it that everyone is willing to readily accept money as compensation? It is primarily because they can always use it whenever required to acquire any goods or service they desire. Because of the existence of money, it is possible to separate in time the act of sale of goods and services from any subsequent acquisition of goods and services.

In the absence of money, we would have to exchange goods and services for other goods and services, a phenomenon that is termed barter or countertrade.

Money as a Store of Value

Money also serves as a store of value, or as a reserve of future purchasing power. However, just because an item is a store of value, it does not necessarily mean it is a good store of value. In the case of money, inflation or the erosion of its purchasing power is a virtually constant feature.

Take the example of a good that costs $2 per unit. If an investor has $10 with him, he can acquire five units. However, if he were to keep the money with him for a year, he may find that the price in the following year is $2.50 per unit, so he can only acquire four units.

Money Is Perfectly Liquid

What is a liquid asset? An asset is defined as liquid if it can be quickly converted into cash with little or no loss of value. Why is liquidity important? In the absence of liquidity, market participants will be unable to transact quickly at prices that are close to the true or fair value of the asset. Buyers and sellers will need to expend considerable time and effort to identify each other, and very often they will have to induce a transaction by offering a large premium or discount. If a market is highly liquid at a point in time, it means that plenty of buyers and sellers are available. In an illiquid or thin market, a large purchase or sale transaction is likely to have a major impact on prices. A large purchase transaction will send prices shooting up, whereas a large sale transaction will depress prices substantially. Liquid markets therefore have a lot of depth, as characterized by relatively minimal impact on prices. Liquid assets are characterized by three attributes: (1) price stability, (2) ready marketability, and (3) reversibility.

In these respects, money is the most liquid of all assets because it need not be converted into another form in order to exploit its purchasing power.

However, liquid assets come with an attached price tag. The more liquid the asset in which an investment is made, the lower the interest rate or rate of return from it. Thus, there is a cost attached to liquidity in the form of the interest forgone because of the inability to invest in an asset paying a higher rate of return. Such interest that is forgone is lost forever, and cash is the most perishable of all economic assets.

Equity Shares

Equity shares or shares of common stock of a company are financial claims issued by the firm that confer ownership rights on the investors, who are known as shareholders. Every shareholder is a part owner of the company that has issued the shares, and her stake in the firm is equal to the fraction of the total share capital of the firm to which she has subscribed. In general, all companies will have equity shareholders, because common stock represents the fundamental ownership interest in a corporation. Thus, a company must have at least one shareholder. Shareholders will periodically receive cash payments called dividends from the firm. In addition, the shareholders are exposed to profits and losses when they seek to dispose off their shares at a subsequent point in time. These profits and losses are referred to as capital gains and losses.

Equity shares represent a claim on the residual profits after all of the company's creditors have been paid. In other words, a shareholder cannot demand a dividend as a matter of right. The creditors of a firm, including those who have extended loans to it, enjoy priority from the standpoint of payments and are therefore ranked higher in the pecking order.

Equity shares have no maturity date. They continue to exist as long as the firm itself continues to exist. Shareholders have voting rights and a say in the election of the board of directors. If the firm were to declare bankruptcy, then the shareholders would be entitled to the residual value of the assets after the claims of all other creditors have been settled. Creditors enjoy primacy compared to shareholders.

The major difference between the shareholders of a company as opposed to a sole proprietor or the partners in a partnership is that they have limited liability: that is, no matter how serious the financial difficulties facing a company may be, neither it nor its creditors can make financial demands on the common shareholders. The maximum loss that a shareholder may sustain is limited to her investment in the business.

Debt Securities

A debt instrument is a financial claim issued by a borrower to a lender of funds. Unlike equity shareholders, investors in debt securities are not conferred with ownership rights. These securities are merely IOUs (an acronym for “I owe you”) that represent a promise to pay interest on the principal amount either at periodic intervals or at maturity, as well as to repay the principal itself at a prespecified maturity date.

Most debt instruments have a finite life span—that is, a stated maturity date—and hence differ from equity shares in this respect. Also, the interest payments that are promised to the lenders at the outset represent contractual obligations on the part of the borrower. In other words, the borrower is required to meet these obligations irrespective of the performance of the firm in a given financial year. It is also the case that, in the event of an exceptional performance, the borrowing entity does not have to pay any more to the debt holders than what was promised at the outset. It is for this reason that debt securities are referred to as fixed income securities. The interest claims of debt holders have to be settled before any residual profits can be distributed by way of dividends to shareholders. In the event of bankruptcy or liquidation, the proceeds from the sale of assets of the firm must be used to first settle all outstanding interest and principal. Only the residual amount, if any, can be distributed among the shareholders.

Although debt is important for a commercial corporation, in both the public and the private sectors of an economy, it is absolutely indispensable for central or federal, state, and local (municipalities) governments when they wish to finance their developmental activities. Such entities cannot issue equity shares. For instance, a U.S. citizen cannot become a part owner of the state of Illinois.

Debt instruments can be secured or unsecured. In the case of secured debt, the terms of the contract will specify the assets of the firm that have been pledged as security or collateral. In the event of the failure of the company, the bondholders have a right over these assets. In the case of unsecured debt securities, the investors can only hope that the issuer will have the earnings and liquidity to redeem the promise made at the outset.

Debt instruments can be either negotiable or nonnegotiable. Negotiable securities are instruments that can be endorsed from one party to another, so they can be bought and sold easily in the financial markets. A nonnegotiable instrument is one that cannot be transferred. Equity shares are negotiable securities. Although many debt securities are negotiable, certain loan-related transactions such as loans made by commercial banks to business firms, as well as individuals' savings bank accounts, are examples of assets that are not negotiable.

Debt securities are referred to by a variety of names such as bills, notes, bonds, and debentures. In the United States, the word debenture is used to refer to unsecured debt securities. U.S. Treasury securities are fully backed by the federal government and have no credit risk associated with them. The term credit risk refers to the risk that the issuer may default or fail to honor his commitment. The interest rate on Treasury securities is used as a benchmark for setting the rates of return on other, more risky securities. The U.S. Treasury issues three categories of marketable debt instruments: T-bills, T-notes, and T-bonds. Also known as zero coupon securities, T-bills are discount securities—that is, they are sold at a discount from their face value and do not pay any interest. They have a maturity at the time of issue that is less than or equal to one year. T-notes and T-bonds are sold at face value and pay interest periodically. A T-note is akin to a T-bond but has a time to maturity between 1 and 10 years at the time of issue, whereas T-bonds have a life of more than 10 years.

Preferred Shares

Preferred stocks are a hybrid of debt and equity. They are similar to debt in the sense that holders of such securities are usually promised a fixed rate of return. However, such dividends are payable from the post-tax profits of the firm, as in the case of equity shares. On the other hand, interest payments to bond holders are made from pretax profits and therefore constitute a deductible expense for tax purposes.

If a company were to refrain from paying the preferred dividends in a particular year, then the shareholders, unlike the bondholders, cannot take legal recourse as a matter of right. Most preferred shares are cumulative in nature. This implies that any unpaid dividends in a financial year must be carried forward, and the accumulated dividends must first be paid before the company can contemplate the payment of dividends to equity shareholders.

Preferred shareholders have restricted voting rights: they usually do not enjoy the right to vote unless the payment of dividends due to them is in arrears. In the event of liquidation of the firm, the preferred shareholders will have to be paid off before the claims of the equity holders can be entertained. The order of priority of the stakeholders of the firm from the standpoint of payments is bondholders first, preferred shareholders second, and then equity shareholders. The term preferred arises because such shareholders are given preference over equity shareholders, and not because the shareholders prefer such instruments.

Foreign Exchange

The term foreign exchange refers to transactions pertaining to the currency of a foreign nation. Foreign-exchange markets are markets in which foreign currencies are bought and sold. A foreign currency is also a type of financial asset, and it will have a price in terms of another currency. The price of one country's currency in terms of the currency of another is referred to as the exchange rate. Foreign currencies are traded among a network of buyers and sellers, comprising mainly commercial banks and large multinational corporations, and not on an organized exchange. The market for foreign exchange is referred to as an over-the-counter (OTC) market. Physical currency is rarely paid out or received. What happens is that currency is transferred electronically from one bank account to another.

Derivatives

Derivative securities, which are more appropriately termed derivative contracts, are assets that confer on their owners certain rights or obligations as the case may be. These contracts owe their availability to the existence of markets for an underlying asset or a portfolio of assets on which such agreements are written. In other words, these assets are derived from the underlying asset. If we perceive the underlying asset as the primary asset, then such contracts may be termed as derivatives, because they are derived from such assets.

The three major categories of derivative securities are (1) forward and futures contracts, (2) options contracts, and (3) swaps.

Forward and Futures Contracts

In a typical transaction, where the exchange of cash for the asset being procured takes place immediately—which is referred to as a cash or spot transaction—the buyer has to hand over the payment for the asset to the seller as soon as the deal is struck; in turn, the seller has to transfer the rights to the asset to the buyer at the same point in time. However, in the case of a forward or a futures contract, the actual transaction does not take place when an agreement is reached between the two parties. What happens in such cases is that, at the time of negotiating the deal, the two parties merely agree on the terms on which they will transact at a future point in time. The actual transaction per se occurs only at a future date that is decided at the outset and at a price that also is decided at the beginning. No money changes hands when two parties enter into such a contract. However, both parties to the contract have an obligation to go ahead with the transaction on the predetermined date as per the agreed-upon terms, as illustrated in Example 1.1. Failure to do so will be tantamount to default.

WIPRO Technologies has imported products from Frankfurt and has entered into a forward contract with HSBC to acquire €500,000 after 60 days at an exchange rate of 62.50 India rupees (INR) per euro. This is a forward contract, because even though the terms and conditions, including the exchange rate, are fixed at the outset, the currency itself will be procured only 60 days after the date of the agreement. Sixty days hence, WIPRO will be required to pay INR 31,250,000 to the bank and accept the euros. The bank, per the contract, is obliged to accept the Indian currency and deliver the euros.

Forward contracts and futures contracts are similar in the sense that both require (1) the buyer to acquire the underlying asset on a future date and (2) the seller to deliver the asset on that date. And, in the case of either kind of security, both the buyer and the seller have an obligation to perform at the time of expiration of the contract. However, there is one major difference between the two types of contracts. Futures contracts are standardized, whereas forward contracts are customized. The terms standardization and customization may be understood as follows. In any contract of this nature, certain terms and conditions need to be clearly defined. The major terms that should be made explicit are the following:

- The number of units of the underlying asset that have to be delivered per contract;

- The acceptable grade or grades that may be delivered by the seller;

- The place or places were the seller is permitted to deliver; and

- The date or, in certain cases, the time interval during which the seller must deliver.

In a customized contract, the above terms and conditions have to be negotiated between the buyer and the seller of the contract. The two parties are at liberty to incorporate any features that they can mutually agree on. Forward contracts come under this category. In standardized contracts, however, a third party will specify the allowable terms and conditions. The two parties to the contract have to design the terms and conditions within the framework specified by the third party and cannot incorporate features other than those that are specifically allowed. The third party in the case of futures contracts is the futures exchange, which is the trading arena where such contracts are bought and sold.

Options Contracts

As we have mentioned, both forward as well as futures contracts, despite the differences inherent in their structures, impose an obligation on both the buyer and the seller. The buyer is obliged to take delivery of the underlying asset on the date that is agreed on at the outset, and the seller is obliged to make delivery of the asset on that date and accept cash in lieu.

Options contracts are different. Unlike the buyer of a forward or a futures contract, the buyer of an options contract has the right to go ahead with the transaction subsequent to entering into an agreement with the seller of the option. The difference between a right and an obligation is that a right need be exercised only if it is in the interest of its holder, and if she deems it appropriate. The buyer or holder of the contract does not face a compulsion to subsequently go through with the transaction. However, the seller of such contracts always has an obligation to perform if the buyer were to deem it appropriate to exercise her right. Example 1.2 illustrates this.

Peter Norton has acquired an options contract that gives him the right to buy 100 shares of GE at a price of $42.50 per share after three months from Mike Selvey. If the price of GE shares after three months were to be greater than $42.50 per share, it would make sense for Peter to exercise his right and acquire the shares. Otherwise, if the share price were to be lower than $42.50, he can simply forget the option and buy the shares in the spot market at a lower price. Notice that he is under no compulsion to exercise the option: it confers a right on the holder but does not impose an obligation. However, if Peter were to decide to exercise his right to buy, Mike would have no choice but to deliver the shares at a price of $42.50 per share. Options contracts always impose a performance obligation on the seller of the option, if the option holder were to exercise his right. The reason is that when two parties enter into an agreement for a transaction that is scheduled for a future date, then at the time of expiration of the contract, a price move that translates into a profit for one of the two parties will lead to a loss for the other. We cannot have a contract that confers to both parties the right to perform, because the party who is confronted with a loss will simply refuse to perform. We can have contracts that impose an obligation on both, such as forward and futures contracts, or else we can have a contract that confers a right on one party and imposes an obligation on the other, which is essentially what an options contract does.

When a person is given a right to transact in the underlying asset, the right can take on one of two forms: he may either have the right to buy the underlying asset or else he may have the right to sell the underlying asset. Options contracts that give the holder the right to acquire the underlying asset are known as call options. If the buyer of such an option were to exercise his right, the seller of the option is obliged to deliver the underlying asset as per the terms of the contract. Peter, in the above example, possesses a call option.

There exist options contracts that give the holder the right to sell the underlying asset. These are known as put options. In the case of such contracts, if the holder were to decide to exercise his option, the seller of the put is obliged to take delivery of the underlying asset.

Options give the holder the right to buy or sell the underlying asset. If the contract were to permit exercise only at the time of expiration, the option, whether a call or a put, is known as a European option. If such an option is not exercised at the time of expiration, then the contract itself will expire. There exists another type of contract in which the holder has the right to transact at any point in time between the time of acquisition of the right and the expiration date of the contract. These are referred to as American options. The expiration date is the only point in time at which a European option can be exercised, and it is the last point in time at which an American option can be exercised.

An options contract, whether a call or a put, requires the buyer to pay a price to the seller at the outset for giving him the right to transact. This price is known as the option price or option premium. This price is nonrefundable if the contract were not to be exercised subsequently. If and when an options contract is exercised, the buyer will have to pay a price per unit of the underlying asset if he is exercising a call option, and he will have to receive a price per unit of the underlying asset if he is exercising a put option. This price is known as the exercise price or strike price.

Futures and forward contracts, however, do not require either party to make a payment at the outset, because they impose an equivalent obligation on both the buyer and the seller. The futures price, which is the price at which the buyer will acquire the asset on a future date, will be set in such a way that the value of the futures contract at inception is zero from the standpoint of both the buyer and the seller.

Swaps

A swap is a contractual agreement between two parties to exchange cash flows calculated on the basis of prespecified terms at predefined points in time.

The cash flows being exchanged represent interest payments on a specified principal amount, which are computed using two different yardsticks. One interest payment may be computed using a fixed rate of interest, whereas the other may be based on a variable benchmark such as the T-bill rate.

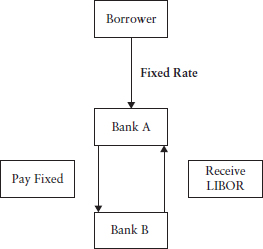

A swap in which both payments are denominated in the same currency is referred to as an interest rate swap. The motivation for such a transaction may be understood as follows. Consider the case of a commercial bank that has entered into a fixed-rate loan with one of its clients. It may now be of the opinion that interest rates are going to rise. Renegotiation of the loan may not be feasible. Even if it were, it would involve substantial legal and administrative efforts. It would be much easier for the bank concerned to enter into a swap transaction with an institution, perhaps another commercial bank, wherein it pays a fixed rate of interest and receives a variable rate based on a benchmark such as the London interbank offer rate (LIBOR). By doing so, it would have converted its fixed-rate income stream to a floating-rate income stream and would stand to benefit if interest rates rise as anticipated. In a nutshell, the objective of a swap is to enable a party to dispose of a cash-flow stream in exchange for another cash-flow stream. Diagrammatically we can depict the above transaction as follows.

There also exist swaps where two parties exchange cash flows denominated in two different currencies. Such swaps are referred to as currency swaps.

Mortgages and Mortgage-Backed Securities

A mortgage is a loan that is backed by the collateral of specified real estate property. The borrower of funds, the mortgagor, is obliged to make periodic payments to the lender, the mortgagee, in order to retire the debt. In the event of the mortgagor defaulting, the lender can foreclose the mortgage, which means that she can take over the property in order to recover the balance that is due her.

A mortgage by itself is a fairly illiquid asset for the party that makes the loan to the home buyer. Such lenders are called originators. To rotate their capital, lenders will typically pool mortgage loans and issue debt securities that are backed by the underlying pool. Such securities—the cash flows for which arise from the payments made by borrowers of the underling loans—are referred to as mortgage-backed securities. The process of converting an illiquid asset such as a home loan into liquid marketable securities is referred to as securitization. Although very common in the case of mortgage lending, the process of securitization is not restricted to such loans. Receivables from automobile loans and credit card receivables are also securitized. The securities generated in the process are referred to as asset-backed securities.

Hybrid Securities

A hybrid security combines the features of more than one type of basic security. We will discuss two such assets: convertible bonds and warrants.

A convertible bond is a debt security that permits the investor to convert the bond into shares of equity at a predecided rate. Until and unless the investor converts the bond, it will continue to trade in the form of a standard debt security. The interest rate on such bonds will be lower than on securities without the option to convert, because the conversion feature will be perceived as a sweetener by potential investors. The rate of conversion from debt into equity will typically be set in such a way that the conversion price is higher than the market price prevailing at the time of issue of the debt. A bond with a principal value of $1,000 may be convertible to 25 shares of equity. In this case, the conversion price is $40. In such a case, the share price that is prevailing at the time of issue of the convertible will be less than $40.

A warrant is a right given to the investor that allows her to subscribe to the equity shares of the company at a future date at a predetermined price. Such rights are usually offered along with debt securities in order to make the bonds more attractive to investors. Once issued, the warrants can be detached from the parent security and traded in the secondary market.

Primary Markets and Secondary Markets

The function of a primary market is to facilitate the acquisition of new financial instruments by investors, both institutional and individual. When a company goes in for an issue of equity shares to the public, it will be termed a primary market transaction. Similarly, if the government were to raise funds by issuing Treasury bonds, it will once again be termed a primary market transaction.

Once a financial asset has been created and sold to an investor in the primary market, subsequent transactions in that instrument between two investors are said to take place in the secondary market. Assume that GE went in for a public issue of 5 million shares out of which Frank Reitz was allotted 10,000 shares. This would be termed a primary market transaction. Six months hence, Frank sells the shares to Mike Pierce on the New York Stock Exchange. This would constitute a secondary market transaction. Whereas primary markets are used by governments and business entities to raise medium- to long-term capital for making productive investments, secondary markets merely facilitate the transfer of ownership of an asset from one party to another.

Primary markets by themselves are insufficient to ensure the functioning of the free-market system; that is, secondary markets are a sine qua non for the efficient operation of the market economy. Why is this so? Consider an economy without a secondary market. In such an economy, an investor who subscribes to a debt issue would have to hold on to it until its date of maturity. In the case of equity shares, the problem will be more serious, because such securities never mature. The acquirer of shares in a primary market transaction and future generations of his family would have no option but to hold the shares forever. No investor will make an investment unless he is confident there exists an avenue for a subsequent sale if he were to decide that he no longer required the investment.

The ability to trade in a security after acquiring it in a primary market transaction is important for two reasons. First, one of the key reasons for investing in financial assets is that they can always be liquidated or converted into cash. Such needs can never be perfectly predicted, and investors would desire access to markets that facilitate the ready conversion of securities to cash and vice versa. Second, most investors do not hold their wealth in the form of a single asset, but prefer to hold a basket or portfolio of securities. As the old adage says, “Don't keep all your eggs in one basket.” A prudent investor would seek to diversify her wealth among various asset classes such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and precious metals such as gold. This kind of diversification will usually be taken a step further in the sense that the entire wealth that an investor has earmarked to be held in stocks will not be invested in the shares of a single company like IBM: a rational investor will diversify across industries, and within an industry she will choose to invest in multiple companies. The logic is that all the companies are unlikely to experience difficulties at the same time. If the workers at GM were to be on strike, it is not necessary that workers at Ford should also be on strike at the same time. If one segment of the portfolio were to be experiencing difficulties, the odds are that another segment would be doing well and will tend to pull up the performance of the portfolio as a whole.

Secondary markets are critical from the standpoint of holding a diversified portfolio of assets. In real life, an investor's propensity to take risk does not stay constant over his life cycle. We know that debt securities promise contractually guaranteed rates of return and are paid off on a priority basis in the event of liquidation. On the other hand, equity shareholders are residual claimants who are entitled to payments only if there were to be a surplus after taking care of the other creditors. The risk of a debt investment will be lower as compared to an equivalent equity investment. Young investors who are having steady and appreciating income usually have a greater capacity to take risk, and they have a tendency to invest more in equity securities. Even from the standpoint of equity shares, young investors are less concerned about steady dividend payments and tend to focus more on the odds of getting significant capital gains in the medium to long term. Senior citizens, on the other hand, want predictable periodic income from their investments and have little appetite for risk. Such investors therefore have a tendency to hold a greater fraction of their wealth in debt securities. If and when such investors acquire equity shares, they display a marked preference for high dividend-paying and less-risky stocks.

As they grow older, investors periodically make perceptible changes in the composition of their portfolios. A young single investor who has recently secured employment may be willing to take more risks and would probably put a greater percentage of her wealth in equities. Later, as her family grows and she approaches middle age with the children ready to go to college, the investor will probably distribute her wealth more or less evenly between debt and equities. A similar redistribution of wealth across asset classes is observed when an investor approaches retirement. Elderly investors tend to have their wealth primarily in the form of debt securities. There is a saying in financial markets that an investor should invest a percentage of his wealth in equity shares that is equal to 100 minus his age—that is, a 30-year-old should have 70 percent of his wealth in equities, whereas a 70-year-old should have 30 percent of his wealth in equities.

From the standpoints of providing liquidity and permitting portfolio rebalancing, it is important to have active secondary markets. In the absence of such markets, the willingness of individuals to save, and the level of investment in the economy, will be severely affected.

Exchanges and OTC Markets

A securities exchange is an organized trading system in which traders interact to buy and sell securities. A securities exchange is a secondary market for securities. Public traders cannot directly trade on these exchanges; they must route their orders through a securities broker who is a member of the exchange. Historically, trading used to take place on a trading floor, where member brokers would congregate and seek to match buy and sell requests received from their clients. These days most exchanges are electronic markets. Traders do not interact face-to-face but are required to key their orders into a computer terminal that conveys the orders to a central processing system. The procedure for matching and executing orders is coded into the software.

Two types of orders can be placed by an investor. In the case of market orders, the investor merely specifies the quantity he seeks with the understanding that he will accept whatever price he is offered. However, investors who are very particular about the price they pay or receive will place what are known as limit orders. The limit orders require not only a specified quantity but also a limit price. The limit price is a ceiling in the case of buyers—that is, it represents the maximum amount that the investor is willing to pay. In the case of sell orders, the limit price is a floor that represents the lowest price at which the investor is willing to sell. To ensure that traders are given access to the best available prices, all limit buy orders are ranked in descending order of price while limit sell orders are ranked in ascending order of price. This is known as the price priority rule. Potential buyers are given access to the lowest price on the sell side while potential sellers are given access to the highest price on the buy side. If two or more limit buy or sell orders were to have the same limit price, then the order that came in first would be ranked higher. This is known as the time priority rule.

Newer exchanges such as Eurex in Frankfurt are fully automated electronic systems. Some of the older exchanges have changed with the times and have abandoned their trading rings or floors and embraced electronic trading platforms. However, some of the other older exchanges are relatively resistant to change. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the CME Group continue to run floor-based and screen-based trading platforms in parallel.

An OTC network is an informal network of securities brokers and dealers who are linked by phone and fax connections. Most deals on such markets tend to be institutional in nature and are of sizable volume. The foreign-exchange market globally is an OTC market, and most of the trading in bonds also takes place on such markets.

Table 1.1 shows the leading stock exchanges ranked in terms of the value of trades in 2010.

Table 1.2 shows the leading exchange groups by market capitalization.

Table 1.3 shows the leading derivative exchanges by contract volume.

Table 1.1 The World's Leading Stock Exchanges (Value of Trades-Electronic Order Book Trades)

| Exchange | Value of Trades ($ Trillion) in 2010 |

| NYSE Euronext (US) | 17.80 |

| NASDAQ OMX | 12.66 |

| Shanghai Stock Exchange | 4.49 |

| Tokyo Stock Exchange Group | 3.79 |

| Shenzhen Stock Exchange | 3.56 |

| London Stock Exchange Group | 2.75 |

| NYSE Euronext (Europe) | 2.02 |

| Deutsche Boerse | 1.63 |

| Korea Exchange | 1.60 |

| Hong Kong Exchanges | 1.50 |

| Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) Group | 1.37 |

| BME Spanish Exchanges | 1.36 |

| Australian Securities Exchange | 1.06 |

Source: www.world-exchanges.org

Table 1.2 The World's Leading Stock Exchanges (Market Capitalization) as of 31 December 2010

| Exchange | Capitalization ($ Billion) |

| NYSE Euronext | 15.97 |

| NASDAQ OMX | 4.93 |

| Tokyo Stock Exchange | 3.83 |

| London Stock Exchange | 3.61 |

| Shanghai Stock Exchange | 2.72 |

| Hong Kong Stock Exchange | 2.71 |

| Toronto Stock Exchange | 2.17 |

| Bombay Stock Exchange | 1.63 |

| National Stock Exchange of India | 1.60 |

| BM&F Bovespa | 1.55 |

| Australian Securities Exchange | 1.45 |

| Deutsche Boerse | 1.43 |

| Shenzhen Stock Exchange | 1.31 |

| SIX Swiss Exchange | 1.23 |

| BME Spanish Exchanges | 1.17 |

| Korea Exchange | 1.09 |

| MICEX | 0.95 |

| JSE Limited | 0.93 |

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Table 1.3 The World's Leading Derivatives Exchanges (Contract Volumes)

| Exchange | Contracts (Millions) January–December 2010 |

| Korea Exchange | 3748.86 |

| CME Group | 3080.49 |

| Eurex | 2642.09 |

| NYSE Euronext | 2154.74 |

| National Stock Exchange of India | 1615.79 |

| BM&F Bovespa | 1422.10 |

| CBOE | 1123.51 |

| NASDAQ OMX | 1099.44 |

| Multi Commodity Exchange of India | 1081.81 |

| Russian Trading Systems Stock Exchange | 623.99 |

| Shanghai Futures Exchange | 621.90 |

| Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange | 495.90 |

| Dalian Commodity Exchange | 403.17 |

| Intercontinental Exchange | 328.95 |

| Osaka Securities Exchange | 196.35 |

Source: www.futuresindustry.org

Brokers and Dealers

A broker is an intermediary who arranges trades for his clients by helping them to locate suitable counterparties. His compensation is in the form of a commission paid by the client. Brokers do not finance the transaction—that is, they do not carry an inventory of the assets being sought. They are merely facilitators of a trade who receive a processing fee for services rendered. Brokers are very common in real estate markets. If we were to contemplate the purchase of a house, we would approach a realtor. She will have a list of properties whose owners have evinced interest in selling. However, a realtor does not own an inventory of houses that she has financed.

A dealer, on the other hand, is a market intermediary who carries an inventory of the asset in which he is making a market. Unlike a broker, a dealer has funds locked up in the asset. In effect, a dealer takes over the trading problem of the client. If the client is seeking to sell, the dealer will buy the asset from the client in anticipation of being able to resell it at a higher price. Similarly, when a client wishes to buy the asset, the dealer will sell the asset from his inventory in the hope of being able to replenish his stock subsequently at a lower price. To ensure profits from his trading activities, a dealer has to be a master of the art of trading. In developed countries, dealers will usually specialize in narrow segments of the securities market. Some will handle Treasury bonds, whereas others may choose to specialize in municipal debt securities. This is because, considering the volumes of transactions, skill is of the essence, and even small errors could lead to huge losses given the magnitude of the deals.

How does a dealer make money? The price he quotes for acquiring an asset will be less than the price at which he expresses his desire to sell to another party. The price at which a dealer is willing to buy from a client is called the bid, and the price at which he is willing to sell to a client is called the ask. The difference between the bid and the ask is called the bid – ask spread or simply the spread. Dealers seek to make money by rapidly rotating their inventories. A purchase at the bid followed by a subsequent sale at the ask will result in a profit equal to the spread. Such a transaction is termed a round-trip transaction.

Many dealers don the mantle of both brokers and dealers. In certain transactions they will act as trade facilitators who provide services in anticipation of a commission, and in other cases they will position themselves on one side of the trade by either buying or selling securities. Such dealers are called dual traders. A transaction in which the dealer functions merely as a broker is referred to as an agency trade. However, a trade in which the dealer is one of the parties to the transaction is termed a proprietary trade.

Dealers who undertake to provide continuous two-way price quotes are referred to as market makers. Their role is to create a liquid secondary market. On the NYSE, there is only one market maker for a security, although one dealer may make a market in multiple securities. This monopolist market maker is referred to as a specialist. She is also known as an assigned dealer because the role has been assigned to her by the exchange. When a company seeks to list its securities on the exchange, a number of potential market makers will express their desire to act as the specialist for the stock being introduced. They will be interviewed by representatives of the company as well as the exchange, and finally one of them will be selected as the specialist for that particular stock.

There are also interdealer brokers who act as intermediaries for trades between market makers. These include ICAP, Tullett Prebon, GFI, Tradition, and Cantor Fitzgerald. Cantor Fitzgerald got global publicity for extremely unfortunate reasons. It was occupying the top floors of the World Trade Center, and 658 employees perished in the attack on September 11, 2001.

The Need for Brokers and Dealers

Why do we require market intermediaries such as brokers and dealers? The reason is that when an investor seeks to buy or sell assets in the secondary market, she has to locate a suitable counterparty. A potential buyer needs to locate a seller and vice versa. Second, a counterparty not only should be available but also there should be compatibility in terms of price expectations of the two parties, and the quantity that each one is seeking to transact. Every trader seeks to trade at a price that is good from her standpoint. Buyers will therefore be on the lookout for sellers who are willing to offer securities at prices that are less than or equal to what they are willing to pay. Similarly, sellers will seek to locate buyers who are willing to offer a price that is greater than or equal to the price at which they are willing to sell. As explained earlier, limit orders are arranged in descending order of the limit price on the buy side and in ascending order of the limit price on the sell side. Buyers are guaranteed access to the lowest prices quoted by sellers, whereas sellers are guaranteed access to the highest prices quoted by buyers. In addition, it is important that the quantity on offer matches the quantity being demanded. Often a large buy or sell order may require more than one buyer to take the opposite position before execution.

On an organized exchange, it is necessary to go through a broker or a dealer for certain reasons. First, access to the exchange is only provided to registered brokers and dealers. For exchanges that are totally automated, only brokers and dealers will have terminals through which orders can be routed to the central processing system of the exchange. It is essential for a public trader to go through a licensed market intermediary. Of course, big institutional investors may be provided with order-routing systems so that they can seamlessly send orders to the exchange via the intermediary. On exchanges that have floor-based trading, only regular traders will be familiar with the jargon and protocol that is required for trading. Allowing a novice to step in would cause unnecessary chaos and confusion.

Second, exchanges insist on dealing with market intermediaries to reduce the possibility of settlement failure. The term settlement here refers to the delivery of securities from the seller to the buyer and the delivery of cash from the buyer to the seller. Default on the part of either party to a transaction can substantially affect the public's confidence in the system. To prevent settlement failure, exchanges have elaborate risk-management systems in place. Market intermediaries are required to post performance guarantees or collateral called margins with the exchanges to rule out the possibility of a failed trade. It would make sense for a party to have such a financial relationship with the exchange only if he trades regularly and in large volumes. For public traders who trade relatively infrequently, developing such an arrangement with the exchange is not practical. However, brokers and dealers who either trade regularly on their own account or have a large number of trades routed through them will find it worth the cost and effort to have such a financial relationship with the exchange.

The brokerage industry has been deregulated in most countries. Before deregulation, a minimum brokerage fee was specified by the authorities. What was happening, therefore, was that institutional clients were subsidizing retail clients: institutional clients were paying more than they should have, considering the magnitude of their transactions, whereas retail investors were paying less than what they should have paid. The immediate impact of deregulation was a sharp increase in retail brokerage rates. However, a brand-new industry—discount brokerage—was born as a consequence. A regular broker—referred to as a full-service broker—will sit one-on-one with his client seeking to ascertain his investment objectives in order to provide suitable recommendations. He will also provide extensive research reports to facilitate decision making. A discount broker, on the other hand, will offer no advice. Her only task is to execute orders placed by her clients. There is also a category of brokers referred to as deep-discount brokers. These brokers also provide no investment-related advice. However, they insist on transactions of a substantial magnitude and charge commissions that are even less than those levied by discount brokers.

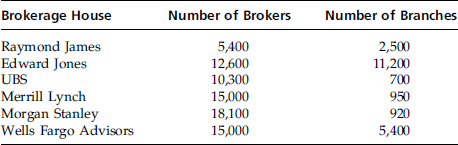

Table 1.4 lists major full-service brokers.

Table 1.5 lists major discount-brokerage firms.

Table 1.4 Full-Service Brokers

Source: www.smartmoney.com

Table 1.5 Discount-Brokerage Firms

| Zecco |

| TradeKing |

| E*TRADE |

| ShareBuilder/ING Direct |

| OptionsXpress |

| Scottrade |

| Fidelity |

| Vanguard |

| Charles Schwab |

| TD Ameritrade |

Source: moneybluebook.com

Trading Positions

A trader is said to have a long position when he owns an asset. An investor with a long position will gain if the price subsequently rises and will lose if it subsequently falls. A rise in price will constitute a capital gain at the time of sale, whereas a price decline is termed a capital loss. The principle behind the assumption of such a position is buy low and sell high. Investors who take long positions in anticipation of rising prices are said to be bullish in nature and are termed bulls.

All traders in the market need not be bullish about the future. Some may be of the opinion that prices are going to decline. Such investors will assume what are termed short positions. A trader is said to have taken a short position when he has sold an asset that he does not own. This is accomplished by borrowing the asset from another investor. Such a transaction is called a short sale. In such cases, the trader will have to eventually purchase the asset and return it to the lender. If his reading of the market is correct, and prices do decline by the time the asset is bought back, he stands to make a profit. When a person with a short position acquires the asset, he is said to be covering his position. Short sellers therefore seek to sell high and buy low. Short selling is considered a bearish activity, and such investors are termed bears.

The Buy Side and the Sell Side

The trading industry as a whole can be classified into a buy side and a sell side. The buy side consists of traders who seek to buy the services being offered by the exchange. The traders on the sell side are those who are offering the services of the exchange. The terms buy side and sell side have no implications for the purchase and sale of securities. Traders on both sides of the market regularly buy and sell securities.

Of all the services offered by the exchange, the key is liquidity. Sell-side traders sell liquidity to the buy-side traders by giving them the opportunity to trade whenever they desire. The buy side consists of individuals, investment funds, institutions, and governments that use the markets to achieve objectives such as cash-flow management or risk management. The sell side consists of brokers and dealers who help buy-side traders trade at their convenience.

Investment Bankers

An investment banker is an investment professional who facilitates the issuance of securities in the primary market. These institutions help the issue process in two ways. First, they help the borrower comply with various legal and procedural requirements that are usually mandatory for such issues. A prospectus or an offer document must accompany any solicitation efforts for the issue. Most issues have to be registered with the capital markets regulator of the country, which is the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States. Finally, most issues are listed on at least one stock exchange. Listing is a process by which an exchange formally admits the issue for trading between investors after the securities have been allotted.

Second, investment bankers provide insurance to the issuer by underwriting the issue. This means that they stand ready to buy that portion of the issue that remains unsubscribed if the issue were to be undersubscribed. Underwriting helps in two ways: (1) it reduces the risk for the issuer, and (2) it sends a positive signal to the potential investors about the quality of the issue, because the investment banker stands ready to buy whatever they choose not to subscribe to. To give an example, consider an issue that has been underwritten by UBS. This means that if investors do not subscribe to the entire amount on offer, UBS will accept the remainder. This would reassure a potential investor because a bank like UBS would not give such an undertaking without doing its homework. In certain cases, an investment bank may not desire to take the entire risk of a new security issue on itself, because the issue may be very large or else may be perceived to be extra risky. A group of investment banks may underwrite the issue together, thereby spreading the risk. This is called syndicated underwriting. The chief underwriter is referred to as the lead manager. The next rung of investment bankers are co-managers. There is also a selling group associated with most issues. It consists of relatively smaller investment banks that do not underwrite the issue but that have been roped in because of their expertise in marketing such issues in their zones of influence.

At times, instead of underwriting the issue, the investment bank will offer to sell it on a best-efforts basis. In other words, the bank will merely offer to do its level best to ensure that the issue is fully subscribed. In these cases, the investment bank merely performs a marketing function without providing the insurance that characterizes the process of underwriting. The banker's commission in such cases will be lower.

Most public offerings are usually underwritten because issuers are more comfortable with such arrangements. This is because the investment bank has a greater incentive to sell the securities when there is a risk of devolvement. What is devolvement risk? It is the risk that the bank may have to buy the unsold securities in the event of undersubscription. Such an eventuality will inevitably lead to a loss for the bank, in the sense that the shares so acquired will have to be subsequently offloaded in the market at a price that is lower than the issue price. This is because devolvement is a clear sign of negative market sentiments about the issue, and an issue that fails will experience a fall in price on listing.

Global Finance chose Goldman Sachs as the best investment bank globally in 2008. Merrill Lynch was selected as the best equity bank, and Citibank as the best debt bank. Deutsche Bank was chosen as the best investment bank in Western Europe, and Merrill Lynch was voted the best bank for both debt and equities. In Asia, Citibank was voted the best investment bank as well as the best bank for debt. UBS was voted the best equity bank.

Direct and Indirect Markets

In a direct market, the surplus budget units in the economy deal directly with the deficit budget units: funds flow directly from the ultimate lenders to the ultimate borrowers. If AT&T were to be making a public issue of shares and an investor were to purchase them, it would be termed a direct market transaction. Similarly, if the government were to issue bonds to individual as well as institutional investors, it also would constitute a direct market transaction. An issuer of equity shares or debt securities can do so either through a public issue or through a private placement. A public issue entails the sale of the issue to a large and diverse body of investors, both retail and institutional. Such issues are usually under-written by an investment banker. In the case of private placements, which are more common for debt issues, the issuer will sell the entire issue directly to a single institution or a group of institutions.

In the case of indirect financing, the ultimate lender does not interact with the ultimate borrower. A financial intermediary in such markets comes in between the eventual borrower and the ultimate lender. The role of such an intermediary is, however, very different from that of a broker-dealer or an investment banker, who also are financial intermediaries albeit in a different sense.