Two. The Modern Portfolio Problem

Is that an Eldorado parked in your portfolio?

The 1959 Cadillac Eldorado “isn’t so much a car as a cathedral,” writes automobile guru Quentin Willson.17 Innovative, cool, rich, and stylish, it came to epitomize America’s post-war swagger. With its space-age style, 390 cubic inch V8 engine and—of course—those fins. “The most telling thing about the ‘59 is its sheer in-yer-face arrogance,” according to Willson. But the car’s attitude, like the country’s, would soon sputter. By the mid-1960s, the country was mired in war, divided culturally, and in the midst of a serious crisis of national confidence. While the Eldorado captured a moment and was, for its time, the essence of modern, it quickly faded. “A decade of glitz, glamour, and prosperity was coming to an end,” Willson concludes. “America would never be the same again, and neither would her Cadillacs.”

17 Quentin Willson, DK Publishing, “Classic American Cars,” 1997.

Standards are set to be changed. Modern becomes old. And while it is easy to spot an old classic like the Cadillac Eldorado on the road today, it is not so easy for people to spot an outdated investment model. In other words, you may have a brand new SUV in your garage, but it’s possible you still have an Eldorado parked in your portfolio.

Modern Portfolio Theory, or MPT, was first developed by Harry Markowitz in 1952.18 MPT is a theory of finance that attempts to maximize return for a given level of risk. Although revolutionary at the time (for which Markowitz was awarded a Nobel Prize) and a popular strategy of investing for more than 50 years, some of its basic assumptions have been challenged in recent years, especially in the wake of the economic crisis of 2008. It’s not that I think that the theory itself is flawed, rather, it’s that the nature of investing has changed—and changed greatly. As a result, even long-held beliefs have been tested.

18 Harry M. Markowitz, Nobel Prize, Autobiography, 1990.

Somewhere along the way, investors have been encouraged to “set it and forget it”—to pick a rudimentary asset allocation, glance at their quarterly statements, and then file them away. Some have also been taught to rely on that simplistic notion of using their age as the basis of calculating the percentage of their portfolio allocated to fixed income, with the rest going to equities. For example, if they are 30 years old, 30% goes to bonds, with the remaining 70% allocated to equities. As they approach retirement, they begin to increase the amount of their allocation to bonds, resulting in a more conservative portfolio that is historically recommended for retirement. Traditionally, despite dips along the way, the stock market always increased over time, so why worry?

In today’s increasingly fast-paced and interconnected world, such “rules of thumb” may be more harm than help. Those who fail to keep pace with change invariably fall victim to it—and find themselves left behind. Furthering our analogy, when looking under the hood of that vintage Cadillac, the engine may no longer be suitably equipped. And regardless of whether you are investing or driving, there are always associated risks that need to be carefully considered.

The Long and Winding Road: Preparing for the Ride

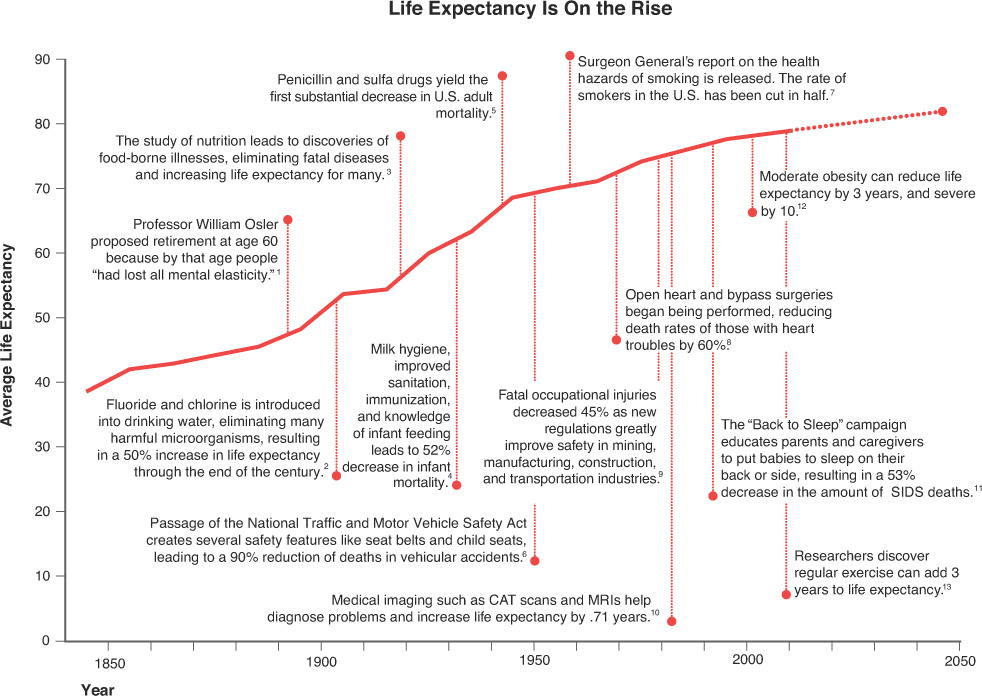

Before we drive ahead, let’s take a quick look in the rearview mirror. At the core of the need for portfolio reconstruction is longevity. For the most part, we are living longer lives than we used to. At the start of the 20th century the average life expectancy was 47.3 years.19 Yet in the next century alone, it lengthened by an additional 63%, due largely to sharp advances in medicine and medical technology.20 In 2000, the average life expectancy at birth for a person born in the United States was 76.8 years, it was projected to be 78.3 years in 2010, and by 2020 it’s predicted to be 79.5 years.21 (See Figure 2.1.)

19 U.S National Center for Health Statistics, “Health, United States, 2011, Table 22,” 2011.

20 Frank Lichtenberg, Columbia University and National Bureau of Economic Research, “The Impact of Biomedical Innovation on Longevity and Health,” August 2012.

21 U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012, “Table 104. Expectation of Life at Birth, 1970 to 2008, and Projections 2010 to 2020,” 2012.

Figure 2.1

1. Alex J. Pollock, American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, “Retirement Finance: Old Ideas, New Reality,” September 2006.

2. Chlorine Chemistry Council, “Chlorine and Drinking Water: Here’s to Your Health,” November 1995; Jamie Knotts, National Drinking Water Clearinghouse, “A Brief History of Drinking Water Regulations,” 1999.

3. Centers for Disease Control, “Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999,” May 2001.

4. Centers for Disease Control, “What Is Public Health? The 20th Century’s Ten Great Public Health Achievements in the United States,” 2012.

5. Population Research Bureau, Research Highlights in the Demography and Economics of Aging, “The Future of Human Life Expectancy: Have We Reached the Ceiling or Is the Sky the Limit?” March 2006.

6. Centers for Disease Control, “Achievements in Public Health 1900-1999 Motor-Vehicle Safety: A 20th Century Public Health Achievement,” 1999.

7. Maggie Fox, NBC News, “50 Years of Progress Cuts Smoking Rates in Half—But Can We Ever Get to Zero?” January 11, 2014.

8. Jim Atkinson, Esquire, “The Future of Your Heart Attack,” 2013.

9. Centers for Disease Control, Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, “Fatal Occupational Injuries—United States, 1980-1997,” April 2001.

10. Dr. Frank Lichtenberg, National Bureau of Economic Research, “Study Demonstrates Significant Increases in Life Expectancy Due to Advanced Medical Imaging,” June 2009.

11. United States Department of Health & Human Services, “Preventing Infant Mortality,” January 2006.

12. National Institutes of Health, NIH News, “Obesity Threatens to Cut U.S. Life Expectancy, New Analysis Suggests,” March 2005.

13. Associated Press, MSNBC, “Exercise Can Add 3 Years to Life Expectancy,” November 2005.

A lot has been written about longevity’s impact on retirement. In my experience, retirement discussions used to revolve around it being a period of “short rest then death” after a lifetime of hard work. However, as life expectancy has increased, the traditional ideas of retirement have transformed. According to gerontologist Dr. Ken Dychtwald, today’s retirees are looking forward to not to just a few remaining, peaceful years, but to an active lifestyle full of travel, second careers, more education, and perhaps even new romances. “People have...had enough chances to watch people play out their retirement to see what happens...” Dychtwald told Investment Advisor in late 2011. “For high-energy, stimulated, and stimulating people, retirement is boring... They’ve looked at their retired relatives and said, ‘That’s not for me.’”22

22 John Sullivan, Investment Advisor, “Retirement Reset,” November 2011.

How could living longer and more fulfilling lives possibly be a problem? It’s quite simple: How will we pay for it?

Employers Stall Out: Finding a New Map to Your Financial Future

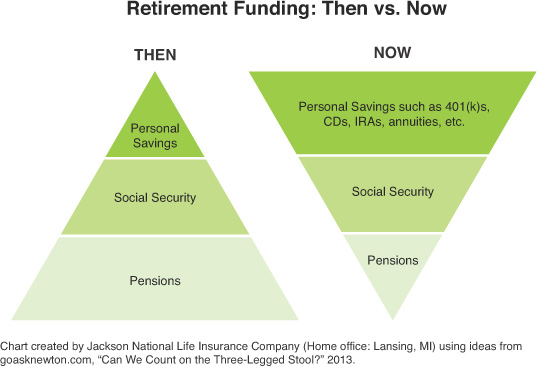

The primary retirement plan for Americans used to be a defined benefit plan, one that promised a specified monthly amount of money upon retirement. Chances are your parents or grandparents (or someone you know) had a defined benefit plan. Simply put, they worked for a set period of time and were then periodically paid a set amount of money for the rest of their life. It might have come in the form of an exact dollar amount, such as $1,000 per month. Or, more commonly, the payment was calculated by using a formula that considers such factors as salary, length of service, and life expectancy.

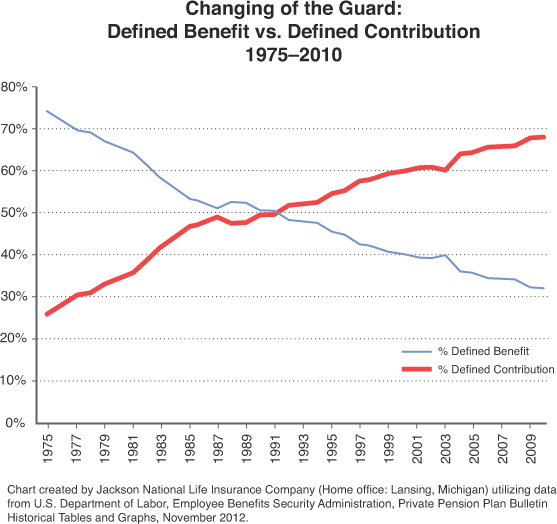

However, the Revenue Act of 1978 created the 401(k), a type of defined contribution plan, by removing payroll taxes on money that was deferred for a later payout.23 Advantages of defined contribution plans included greater control, investment choice, and portability from one job to the next for employees, as well as lower associated costs for employers than defined benefit plans.24 Over time, defined benefit plans faded in popularity and were replaced by defined contribution plans (see Figure 2.2). In 1980, the year the Revenue Act went into effect, almost 66% of private sector workers participated in defined benefit pension plans, while only 34% participated in defined contribution plans. By 2010, the numbers had flipped—68% of private sector workers participated in defined contribution plans while the number of private sector workers in defined benefit plans fell to 32%.25 However, as with any investment program, defined contribution plans do not have the guaranteed payout often seen in pensions. As a result, more responsibility falls on investors interested in retirement planning to calculate how much they will need and to explore additional sources of income, if required.

23 Employee Benefit Research Institute, “History of 401(k) Plans: An Update,” February 2005.

24 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Beyond the Numbers, “Retirement Costs for Defined Benefit Plans Higher Than for Defined Contribution Plans,” December 2012.

25 Employee Benefits Security Administration, U.S. Department of Labor, “Private Pension Plan Bulletin Historical Tables and Graphs,” November 2012.

One common source of retirement income is, of course, Social Security. But longer life spans and the sheer size of the 78 million strong Baby Boomer generation (typically defined as those born between 1946 and 1964)26 may be creating problems for the government program. The Social Security trust fund reserves are expected to run dry in 2033, after which income from taxes will be able to fund only three quarters of each benefit until 2086.27 This leaves anyone planning to retire uncertain of how much, if any, Social Security income they will receive (see Figure 2.3).

26 Daniel Luzer, Washington Monthly, “Old People More Likely to Be College Graduates,” February 2012.

27 Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees, “A Summary of the 2012 Annual Reports,” April 2012.

Throughout this book, I will do my best to illustrate why I think a portfolio model that includes alternatives may help investors in various market conditions and is thus worth considering. The term diversification in this sense is defined as the spreading of assets across different categories or industries. If the stock market rises or falls, alternative asset classes often move independently of both each other and traditional investments, helping to provide further diversification due to their independent characteristics.28 While alternatives do not come without their own set of risks, the worldwide market collapse in 2008 offered few havens—especially in stocks, bonds, and other traditional investments. However, there is evidence that some alternative strategies may have fared better than some of their traditional counterparts. Alternative investments will not always outperform their traditional counterparts, but they may help manage volatility and the reaction to down markets. We will now turn to why.

28 Diversification does not assure a profit or protect against a loss in a declining market. Portfolios that have a greater percentage of alternatives may have great risks, especially those including arbitrage, currency, leveraging, and commodities. This additional risk can offset the benefit of diversification.

From the Alt Vault: Valuable Takeaways from Chapter Two

Longer life spans, the transition from pension models, relying on Social Security, volatile markets, and investor self-reliance and confusion all add up to modern portfolio problems in search of more options. A new movement has taken shape—Generation Alt.

![]() Portfolios need to be periodically reviewed to make sure old and new investing strategies are being taken into account.

Portfolios need to be periodically reviewed to make sure old and new investing strategies are being taken into account.

![]() Pensions are products of a bygone era. Retirement responsibility now falls on the individual.

Pensions are products of a bygone era. Retirement responsibility now falls on the individual.

![]() Increasing life spans mean increasing costs to companies. Defined Contribution plans are now the norm.

Increasing life spans mean increasing costs to companies. Defined Contribution plans are now the norm.

![]() Many financial services companies are taking a closer look at the strategic use of alternative investments to aid a new generation of investors and retirees.

Many financial services companies are taking a closer look at the strategic use of alternative investments to aid a new generation of investors and retirees.

What’s next: Properly used, alternative investments historically reduced volatility and effected returns. The key phrase is properly used—but what, exactly, does that mean?