Chapter 11

Geopolitical Alpha

For much of the past decade, I've worked in finance as a strategist, which requires me to think in narratives and themes but not actually pull the trigger on trades. A navigator plots the course for the airplane, but a passenger wouldn't want him behind the controls actually flying the thing. The execution of investment themes is left for the pilots, the investment professionals who know how to structure a trade to take advantage of a well-articulated strategy. Those are the true “ballers and shot callers” of the financial profession who always humble me, particularly when it comes to implementing my forecasts in the actual marketplace.

I make this distinction lest readers confuse my framework for a trading rule.1

But what I do know how to do is beat the market on geopolitics. The market is not very good at pricing geopolitical risks and opportunities because its behavior is dictated by investment professionals (and retail investors), who all have different time horizons. While they may have good reason to both sell and buy Apple stock at the same time – likely due to their differing time horizons – volatile market reactions indicate they don't know how to price geopolitics. I see a fundamental skills mismatch that creates an opportunity for those investors willing to broaden their skill set.

In Chapter 1, I asserted that the global community of investors has become over-professionalized and overquantified. The CFA curriculum has no section dedicated to simple concepts in political science. It has no case studies to test investors' reactions to the ups and downs of legislative negotiations on fiscal spending. As such, the market consistently over-reacts to geopolitical events as investors try to feel their way through a framework they lack the skills to navigate.2

Educated industry colleagues, clients, and friends have asked me the most bizarrely basic questions. What does a Senate do? What is a nation-state? Who elects the EU president? Does the resignation of the German president matter? Not to mention questions that reveal a shocking level of ignorance concerning foreign political systems. Their blind spot is not because they are stupid or poorly read. It simply takes a lot of hard work to become an investment professional, and for many of them, spending time on politics and history is a luxury they cannot afford.3

This skills mismatch and knowledge gap mean that geopolitical analysis may be the final frontier for the typical investor, and that there is alpha to be harvested in betting against the market. In this book, I introduced a framework for analysis that is particularly good at ignoring the noise generated by social media and news. While the media and policymaker preferences distract each other (as well as ill-equipped investors), a disciplined analyst can focus on material constraints to action.

But this new perspective does not mean that investors should plow headlong into forecasting political events. The key to harvesting geopolitical alpha is betting against the spread, not trying to predict who wins the game.

In sports betting, the astute gambler does not try to predict the outcome of a game. He is indifferent toward the winner of the match because he cannot simultaneously be a gambler and a fan. Success instead lies in “beating the spread” or choosing an “over/under” on the “line” set by the casino.

Some of my worst calls as an investment strategist have been when I forgot this point and tried to bet on who wins the election. And some of my best calls have been when I bet against the bookie: the market.

Take the 2016 UK referendum on EU membership. In March 2016, I argued that the probability of Brexit was closer to 50% than the 30% that the currency and political betting markets had priced in. I did not actually forecast that Brexit would occur. I wrote an analysis in early 2016 asserting that the risk of Brexit was massively understated, but that the Bremain side would win in a tight referendum.

Swing and a miss, right? Wrong! I don't get paid to make forecasts for the sake of politics. I get paid to make forecasts for the sake of the market. Because I thought the market was overly complacent, I recommended a strategy in UK currency, gilts, and equity markets that made money when Brexit did happen.

My approach to politics and geopolitics makes me a terrible dinner guest with “normal people.” For noninvestors – and many investors who can only think ideologically4 – politics is about winning and losing, about politicians doing the wrong or the right thing. They assume there is a right and a wrong – one clear side in which to invest not just money but their hearts and moral standards. But I will bear the dirty looks across the dinner table because my approach allows me to confidently check my work in a field where most are flying blind.

Few political analysts know how to ascertain whether their forecast is correct. One of the most frustrating things about working in the political risk industry was the revisionist performance reviews. A forecast that “the Bashar al-Assad regime would be destabilized by the Arab Spring” can be both right and woefully inadequate at the same time. Sure, Assad has faced a civil war, but he still runs Syria and has beaten back most challengers!

In contrast to politics, markets provide brutal, immediate feedback. Right away, they tell forecasters if they're right because the results of their views are either in green or in red. As such, converting my geopolitical forecasts into trade recommendations has been liberating.

Tensions between Iran and the US are overstated and materially constrained?5 Short oil after it rallies 15% following the attack on Aramco facilities.

If I'm in green, my forecast was sound.

Marine Le Pen's odds of winning are massively overstated in the 2017 French presidential election? Go long EURUSD in Q4 2016.

Then I watch how the market checks my work.

In this chapter, I demonstrate how I use the constraint framework to generate geopolitical alpha. I first review my 2016 analysis on the odds of Le Pen winning the French election. I then go over the process itself, combining the constraint framework with the net assessment process.

Chocolate Labrador Brian Versus Marine Le Pen

As I wrote this book, my 13-year-old chocolate lab was dying. He had a great life.6 Born on a small farm outside of Austin, Texas, he spent most of his life in Quebec frolicking in snow. He passed away the same day that I took him to see the Pacific Ocean for the first time in his life. Brian helped me raise my three kids. He has been a nanny, a maid, and a couch. And for that, I thank him.

What Brian didn't realize was that he had also been my analytical crutch whenever I grew frustrated with clients and colleagues. I have no idea how many elections Brian could have won, but it is a lot. Whenever I reached the end of my patience, my go-to retort to some doubting Thomas was, “My chocolate Labrador, Brian, can beat Candidate X in Election Y.”

In late 2016, investors were nervous. Victories for both the Leave side in the UK's EU referendum and Donald Trump had upended their entire framework for thinking about politics. As I talked to clients around the world – both sophisticated and not – I had a shocking revelation: investors were assigning a higher probability to the election of Marine Le Pen because of the anti-establishment victories in the UK and the US.

This logic was wrong on several levels. Investors had failed to account for just how different France was in terms of its political and geopolitical constraints. Sure, the English-speaking median voter was headed in a populist direction, but I have never known the French to follow trends established in the Anglo-Saxon world! I had a clear framework to explain what happened with both the UK and US Anti-establishment votes. The median voter in the Anglo-Saxon world was moving away from the laissez-faire establishment, as discussed in Chapter 1. Populist outcomes were therefore likely in those countries–but not necessarily in France.

In fact, the French median voter was moving away from Euroscepticism – a shift that was the fulcrum constraint to Marine Le Pen's victory. Popular opinion changed because, by late 2016, the migration crisis in Europe was over. Yet almost every investor I talked to was unaware of the clear data on this point (Figure 11.1). The media could not pivot away from the narrative that got them so many clicks, so they kept hammering home the “Europe will be over-run” narrative. But outside the newsrooms, both the median voters and politicians in Europe knew that the migration crisis had ended.

Figure 11.1 Ready my chart: the migration crisis is over.

The French public in particular was eager for reform. I had the toughest time convincing investors of this view, as most were both Anglo-Saxon and rather anti-French! Instead of investing with their heads, many were investing with stereotypes. But after conducting a net assessment of France – just as in-depth as the net assessment of India in Chapter 9 – I concluded that the median voter in France was looking for change. Polls showed that a “silent majority” wanted reforms. Even Marine Le Pen, a populist, tried to capitalize on the shift of the median voter by promising to cut the size of the state and reduce the retirement age. Not very populist of her! Investors ignored this shift, too busy obsessing over her EU and euro policies.

But her view toward European integration is precisely why Le Pen was unelectable. Despite moving toward the median voter on supply-side reforms, Le Pen made a critical blunder. She remained intellectually wedded to her long-held Eurosceptic preference, campaigning on a promise to exit the Euro Area. Her ideological loyalty to this position was a mistake, given France's median voter constraint. Le Pen's long-term support levels were almost the perfect inverse of the country's support level for the common currency (Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 The euro was Le Pen's foil.

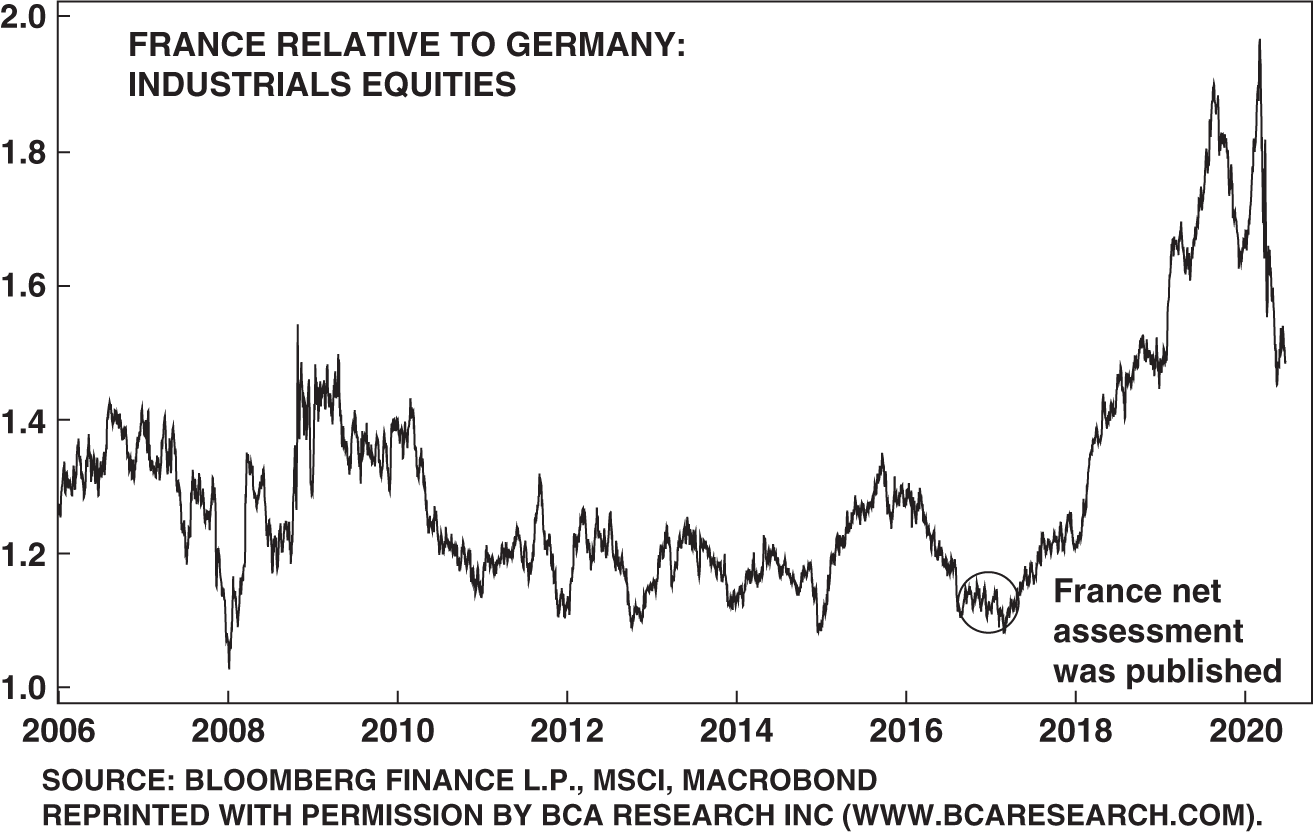

From the results of my constraint-based net assessment, I concluded Marine Le Pen was not a viable candidate. She would get crushed in the second round of the vote by literally anyone – yes, even Brian the Lab. The subsequent government would enact a slew of reforms to close the unit labor cost gap between France and Germany (Figure 11.3).

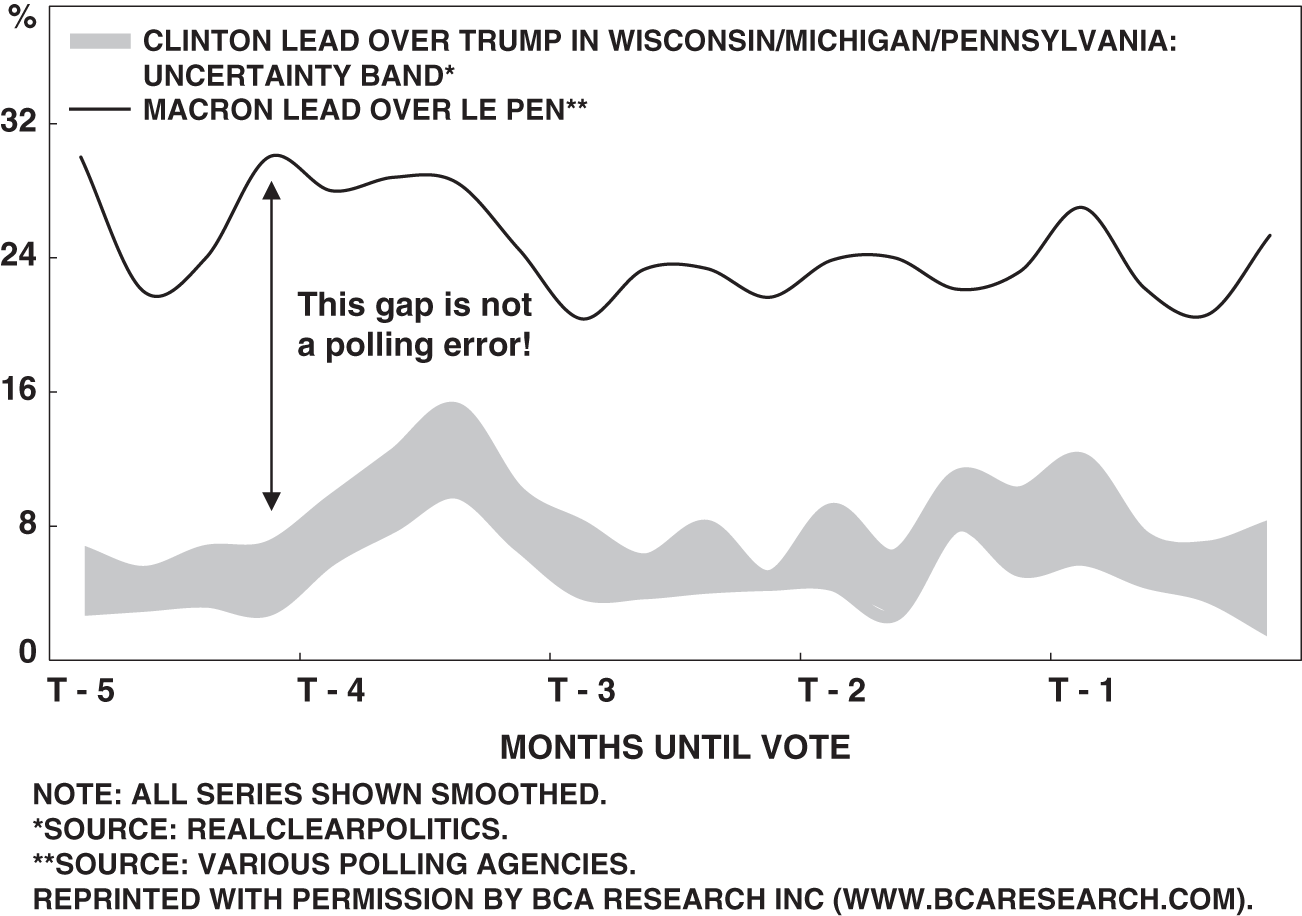

More broadly, investors were catastrophizing Le Pen's candidacy. With two months to the French election, investors were assigning Le Pen a higher probability of winning than they had assigned at the corresponding time to Brexit or Trump's victory (Figure 11.4). This forecasting error was astounding, especially given that Emmanuel Macron's lead over Le Pen at that point was 30%! Compare this gap to the one between Clinton and Trump (Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.3 Structural reforms are coming to France.

Figure 11.4 This chart is insane …

Figure 11.5 … given this chart!!

The market had lost its mind, and I was reaping all the benefits. Despite clear problems with electability and strategy, investors were distracted by poor-quality analysis reliant on historic stereotypes. They bet a 20%–30% electoral lead in the French election would evaporate in three months. I couldn't believe my luck. The bookies, overreacting to a Patriots loss the week before, were expecting the Miami Dolphins to beat Tom Brady … in New England … in December. Mortgage your house, pawn off your own mother, and put money on that line!

I sat down with my BCA colleague Mathieu Savary – a much better investment tactician than me – and we came up with two trades with which to take advantage of my strategy and maximize geopolitical alpha. The first trade, long EURUSD call, was easy enough for anyone to figure out. The euro bottomed on December 20, 2016, and rallied 21% to a peak of 1.250 on January 25, 2018. But the real gem, which required Mathieu's subtle touch, was to go long French industrials/short German industrials (Figure 11.6). The chart speaks for itself.

Figure 11.6 Industrials: buy France/short Germany.

“So, You Want to Go Long Socialism and Short Capitalism”

The market's reaction to Marine Le Pen's candidacy, and my subsequent forecast, show that geopolitical alpha is easiest to harvest when investors confuse stereotyping for analysis. Emotions, anti-French bias, headlines, and a focus on the broad set of the possible – rather than the constrained set of the probable – caused investors to massively overstate the odds of a Le Pen electoral victory.

I love these opportunities. Give me your tired, your poor, your preference-led investors yearning to breathe ideologies! They are easy to bet against when geopolitics are in question.

At the end of my sell-side career in late 2018, I did one final round of my clients in New York and Connecticut. The salesperson ushered me into the office of a legendary hedge fund manager who had made his name in emerging markets (EM). I was particularly bearish on EM in 2019, but I thought there was some alpha to be generated in Mexico and Brazil.

As in France, investors' loss (of median voter perspective) was my gain. I thought investors were overly bullish on Brazil and overly bearish on Mexico. In both countries, the 2018 elections had seen voters turn to anti-establishment candidates due to concerns over violence and corruption. In the wake of these elections, I was skeptical that the Brazilian median voter had suddenly become an acolyte of Reagan and Thatcher or that the Mexican median voter had become a Trotskyite.

Investors expected Brazilian President-elect Jair Bolsonaro to prevail and pass market-friendly reforms, but he had a high hurdle to clear in the constraint of Brazilian legislative math. He had to convince a traditionally fractured Congress to pass a complex and painful pension reform. In other words, Bolsonaro had to show that he could do something in order to justify a rally that had already happened in Brazilian assets.

In Mexico, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) remained constrained by the constitution, the National Supreme Court of Justice, and political convention that Mexico is right of center on economic policy (an outwardly left-wing president had not won an election since 1924). Like Bolsonaro, AMLO had to prove that he could overcome his constraints in order to justify a sell-off that had already happened.

My point is not that AMLO was a positive, in the absolute, for Mexico. His decisions to scrap the Mexico City airport plans, sideline the finance ministry from key economic decisions, and threaten a return to an old-school PRI-era statism was indeed deeply concerning from a market perspective.7 Similarly, I was not of the view that Bolsonaro was, in the absolute, a negative for Brazil.

But the relative investor sentiment was overly bullish Bolsonaro versus AMLO, especially given both presidents' strong political constraints. Ever faithful to my constraint framework, I weighted those constraints more heavily than the leaders' stated economic preferences. I also observed that they faced respective median voters who were diametrically opposed to their economic agendas – Bolsonaro was facing a left-leaning median voter, whereas the Mexican median voter was center-right (at least according to polling).

The macroeconomic context supported my relative view. I thought China would fail to stimulate as much as investors hoped and that the US–China trade war would become a serious risk to investors. If this scenario played out, high-beta countries like Brazil would suffer, while an economy that is joined at the hip to the US, like Mexico, ought to outperform EM peers. My view on USMCA negotiations also happened to be bullish Mexico.

With everything aligning, I recommended a long MXNBRL trade to capture this sentiment gap between the two EM markets. Not only did it make sense given geopolitical constraints, but the market was also screaming for a long MXN trade. For the first time since I had been of legal drinking age, investors would be receiving positive carry on Mexico relative to Brazil (Figure 11.7).

Figure 11.7 Mexico has positive carry vs. Brazil.

I was super stoked that I had at least one positive story to tell on EM.

At the end of AMLO's term, Mexico would not be better off – economically – than Brazil at the end of Bolsonaro's. I wasn't making an absolute call. Imagine that AMLO and Bolsonaro are two NFL teams facing off against one another. The casinos set the line at Bolsonaro crushing AMLO by two touchdowns. I wasn't betting that AMLO would win the game, just that he would narrow the spread. Maybe he would lose by one touchdown, more likely by a field goal.

* * * * *

So, here I am … at the end of my sell-side career, facing the EM legend with a clear, well-thought-out view of how to make money over the next 12 months. I enter his spacious boardroom, shaking hands with him and his second-in-command. We exchange pleasantries and, as we sit down, he says, “So, you're going to tell me how that communist is going to ruin Mexico, right?”

I chuckle earnestly and say, “No, I actually think you should go long the Mexican peso! Let me show you something …”

As I open my chart pack to deliver my strategery, I see Legend's second-in-command lean back, out of his boss's peripheral vision, and slowly shake his head. Maybe. I'm not sure. The movement was almost imperceptible. Ah hell, who cares … it's my last meeting on the sell side, let me crush it.

Forty seconds into my pitch, I notice that Legend's knuckles are white. He stops me.

“Hold on, kid. You're telling me you want to go long communism and short capitalism?”

Uh-oh.

I look at the two gentlemen in front of me, confused. The second-in-command is telepathically telling me to zip it. He is literally sweating.8

Legend says, “I mean … this is just the dumbest f-ing thing I've heard year-to-date.”

It's December.

Normally, such a client judgment would really hurt my feelings.9 But I am checking out of sell side and heading to the beaches of California and don't give a damn. I say, “Well, given that I am the only one here who actually lived under communism, I think that, yeah … I probably know what I'm talking about.”

* * * * *

He didn't buy what I was selling.

Now let me assure you, this man is a Legend. He has made more amazing calls in his career than you, me, and a hundred other investors combined will ever make. But his bias and ideology were his kryptonite on this trade.

This is what is amazing about geopolitical alpha. When I invest based on geopolitical analysis, I am not just investing against peers. Even some of the greatest minds in finance are shooting from the hip, relying on stereotypes and meetings in smoke-filled rooms with deputy finance ministers who tell them what they want to hear. In the constraint framework, all preferences are subject to constraints – not just those of the actors, but those of the analyst as well. Everyone has preferences, but users of the constraint framework have the tools to question the pragmatism in others' as well as their own.

I am no legend, but I bested one that day. Long MXNBRL returned 11.2% from December 14, 2018, when I made the recommendation, until the end of 2019.

Geopolitical Alpha: The Takeaway

The constraint framework gives investors a way to think about geopolitics that is data-driven, focused on the observable, and rooted in the material world. While the media and the pundits focus on policymaker preferences or the dominant narratives, investors can focus on what is actionable: constraints.

Preferences are optional and subject to constraints, whereas constraints are neither optional nor subject to preferences.

The net assessment is the starting point to operationalize this framework. In Chapter 9, I presented examples of two net assessments: a cyclical one and a reactive one. In Chapter 4, I also made a net assessment of where the US median voter is going, arguing that laissez-faire was done. Start getting ready for dirigisme (at best), and outright socialism at the extreme. The explosion of fiscal stimulus is only the beginning.

A net assessment rooted in constraints provides investors with several points of reference. The fulcrum constraint(s) and associated data streams provide the investor with the right metrics to watch. If they change, the view needs to change. Most importantly, a net assessment provides the solid foundation for further analysis: a prior probability for an event or its multiple scenarios. The odds of a US–Iran kinetic conflict are 20% – non-negligible, but less likely than an uneasy truce.

A net assessment can also give investors enough information to choose a bias. My net assessment of Brazil in 2018 gave me a negative bias for the coming year, whereas my net assessment of Mexico gave me a bullish bias. The net assessment of India gives me a bearish bias. This is not an implicit bias rooted in stereotypes or out-of-date tropes, but rather one I chose deliberately that is grounded in research.

Armed with a net assessment and a prior view, investors can make the final gamble and compare it to market pricing and action. What do the valuations say about assets that would be impacted by the geopolitical event under examination?

In this chapter, I illustrated the process of harvesting geopolitical alpha. In the case of Brexit, there was much alpha to harvest as the market was ignoring risks of a Leave victory. In the case of Brazil and Mexico, investors were leaving positive carry on the table purely because of ideological preference. And in the case of the euro, investors were overstating odds of a Marine Le Pen victory.

Geopolitical analysis is rarely effective in a vacuum. In each case of a successful investment call, I've also relied on valuations and market sentiment. As such, just producing a net assessment is not enough. Your assessment has to be out of consensus, or the market may have already priced it in. The constraint framework gives you an edge because it allows you to think outside of the preference-led box.

Notes

- 1 I also stress it so my friends can stop asking me what stocks to buy. I have no idea!

- 2 Ongoing COVID-19-related volatility is similar. Although the initial event – the pandemic itself – is not precisely geopolitical, it does fall under the rubric of noneconomic/finance risks. The pandemic has now evolved into a geopolitical issue, however, as investors have to both assess the spread of the disease and the policy response to the economic calamity.

- 3 There are many finance professionals who do know how to conduct a quality, informed geopolitical analysis. Global macro hedge funds have been incorporating geopolitical and political analysis into their discretionary idea generation for half a century. However, they are a tiny sliver of the broader community. For most investors, geopolitics is new and exotic.

- 4 And are therefore terrible investors.

- 5 As discussed in Chapter 9.

- 6 At least, I think he did. He may disagree …

- 7 PRI is the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or Institutional Revolutionary Party, which governed Mexico from 1929 to 2000.

- 8 Apparently, I was in the office of Bolsonaro's main fan on Wall Street. I had no idea. The man was an old-school, Journal-reading, laissez-faire-worshipping Ayn Rand capitalist. And the thought that I should waltz into his boardroom and suggest he put his hard-earned dollars behind a “communist” over a “capitalist” brought him close to a brain aneurysm.

- 9 I may be a nihilist, but I'm not made of stone!