CHAPTER 20

Portfolio Construction

________________

We have reviewed the world's major sectors and industries and the environment in which global businesses operate, along with the risks we are exposed to when investing in foreign companies. We now explore how an investor can construct a portfolio of good global businesses and build wealth in a safe and effective way. Since we are concerned with building business ownership, we exclude corporate-issued debt as well as preferred shares, both of which represent claims on the cash flows of the business rather than equity ownership. Depending on age and financial circumstances, it may be appropriate for investors to hold bonds or preferred shares in their portfolio (if this is the case, please refer to The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities by Frank Fabozzi, and Financial Statement Analysis by Martin Fridson). This approach assumes that the investor has a long-term investment horizon and will not need to access this money for many years. Additionally, it assumes that the investor has a high-risk tolerance, meaning they have the ability and willingness to endure periods of volatile and/or declining share prices. We begin with a discussion on the types of investment instruments you can buy to obtain ownership in the businesses you like.

Types of Investment Instruments

Common shares of publicly traded companies are my preferred investment instrument because they represent a direct ownership stake in a specific company and can be traded easily on a stock exchange. For some investors, however, buying shares on a foreign stock exchange may be difficult or even impossible. In those situations, investors may be able to buy depositary receipts instead. A depositary receipt is where a third party (often a bank or trust company) holds shares of a foreign company in trust and issues receipts for those shares that will trade on an exchange where the trustee is domiciled. The bank or trust company issuing the depositary receipts acts as a trustee and periodically charges a fee for providing this service. While the fee charged by the trustee is generally small, investors should confirm the fee size prior to purchasing the receipts, as it can be high in some cases. This information is typically available in the depositary receipt's prospectus or on the trustee's website.

A depositary receipt that is listed on a US exchange is known as an American depositary receipt (ADR), and a depositary receipt listed on a European exchange is known as a European depositary receipt (EDR). Other depositary receipts are commonly referred to as global depositary receipts (GDRs). Depositary receipts are equivalent to a prespecified number of common shares of the underlying company, which is known as the conversion ratio. For example, if the depositary receipt's conversion ratio were 20:1, the investor would own 20 shares of the underlying security for each receipt they purchase. This highlights the importance of knowing the conversion ratio for the depositary receipt of any company under consideration.

ADRs can be either sponsored or unsponsored. Sponsored depositary receipts are supported by the issuer of the underlying common shares, while unsponsored receipts are not. Companies with sponsored ADRs must file annual reports with the SEC in the United States, and therefore financial data is readily available (in the English language) for those companies. In comparison, foreign companies tied to unsponsored ADRs are subject to less regulatory scrutiny in the United States and are not required to file annual reports. As a result, there may be less information available about these companies, making them more difficult for investors to analyze. In these instances, investors may need to rely on regulatory filings and company disclosures issued by the company in its home country.

Investors should also understand that dividend payments for ADRs are paid in the currency the receipt is issued in (e.g., US dollars for ADRs and euros for EDRs) and that they may be subject to withholding tax in the same manner as a foreign stock. Investors should consider dividend withholding tax before they invest in a foreign company regardless of whether they purchase a depositary receipt or the company's underlying shares. Dividends that are paid by the company are initially received by the trustee, who then converts the funds into the currency the receipt is denominated in and provides payment to the investor. For example, an ADR representing a Japanese-domiciled company would trade on a US exchange in US dollars and would pay dividends in US dollars even though the underlying cash flows received by the trustee are denominated in Japanese yen. It is important to remember that the returns generated by depositary receipts are affected by the currency the receipt is denominated in as well as by the base currency used by the underlying company. For example, the price of German industrial giant Siemens AG's ADR is affected by exchange rate fluctuations of the company's underlying base currency, the euro, as well as the currency the ADR is traded in, the US dollar.

One of the benefits of owning common shares rather than depositary receipts is better liquidity, which means a higher number of shares are traded each day. The amount of trading that takes place in a company's shares helps determine the ease with which one can transact in the security without impacting the share price. While some depositary receipts trade daily in large volumes, many are thinly traded with only a fraction of the daily trading volume compared to the underlying shares. There are situations when a depositary receipt trades in greater volumes than does the underlying security, but these instances are rare. Avoid investing in securities when the average daily trading volume is so low that it will be difficult for you to sell the shares quickly if you must. Another benefit to owning common shares over depositary receipts relates to voting rights. Readers should note that some depositary receipts do not allow the holder of the receipt to vote the underlying shares. Should the ability to vote on company matters be important to you, it is best to confirm whether owning the receipt will allow you to vote.

Depositary receipts are unfortunately not available for all foreign-listed companies, which may serve as an additional constraint for investors. That said, if an investor is unable to invest directly in a particular business, an ETF or index fund may be their only viable option. As mentioned earlier, buying a passive ETF or index fund means you are investing in substandard businesses at the same time you are investing in the best businesses.

Stick to the Basics (of Investing)

The first step in portfolio construction is to recall the basics of global investing set out in Chapter 8. Own businesses with defensible, leading market positions in growing industries, astute management teams, strong balance sheets, and a strong social conscience, and buy them at attractive prices. When deciding which businesses to own, comparing their relative characteristics to close competitors in their industry and the broader market will provide you with better insights into the company and allow you to make more informed investment decisions.

As outlined in Part Two, avoid investing in countries that do not protect shareholder rights and where reliable financial statements are not readily available. Avoid buying companies that are in countries that have high levels of sovereign or consumer debt, and that are experiencing high or rapidly increasing levels of inflation combined with an overheated housing market. While a good starting point is to set a minimum sovereign credit rating for the countries you invest in (such as an investment-grade rating), continuous monitoring of economic and political events in each country is essential. If that country's regulatory structure is lacking or if shareholder rights are not protected, avoid investing in that country. Also, it is critical that investors fully understand the business they propose to invest in, so having access to information about the company in a language they understand is vital. If this is not possible, then do not invest in the company.

Be Innovative

If you really like the fundamental backdrop for a sector or industry but the companies appear too expensive to warrant an investment, think outside the box and consider alternative ways to take advantage of the opportunity. For example, assume you like the internet retail industry but company valuations are too expensive; you could instead look to the transportation industry and invest in a company positioned to benefit from strengthening e-commerce fundamentals. Similarly, owning a railroad company might be a better way to take advantage of an increased demand outlook for coal as opposed to buying a coal mining company. This is because railroad company shipping volumes would increase since a substantial portion of coal is transported via rail. The same logic can be applied within the commodity space as well. In the case of energy, you might make a direct investment in an energy company with large oil reserves rather than buying oil directly through an ETF or in the futures market. Think of the industry's supply and value chains to look for the most efficient manner to capture the opportunity.

Healthy Diversification

If we knew exactly where we were in the market cycle, the job of building a portfolio would be much easier. The reality is that there is always a degree of uncertainty to investing, and unlikely events occur more often than you would imagine. For this reason, it is prudent to own a variety of businesses that generate sales and earnings in a range of economic sectors as well as different regions of the world. Having a diversified portfolio of complementary businesses will smooth out the underlying earnings stream, not to mention the aggregate price fluctuations in their share prices. This approach, combined with not overpaying for good businesses, will help protect you when stocks enter a bull market correction or a bear market.

In Chapter 8 we discussed how investment risk can be divided into fundamental risk and share price volatility. Share price volatility can be further separated into market risk (also known as systematic risk) and firm-specific risk (also called unsystematic risk). Investors are only compensated for market risk since firm-specific risk can be eliminated by owning a diversified basket of stocks. Many studies have been performed to determine the optimal number of stock holdings needed to eliminate unsystematic risk within a portfolio. While results of those studies varied, there is a widespread belief that investors should own approximately 20 companies in their portfolio. Personally, I have found that owning 20–30 companies in equal weightings provides adequate portfolio diversification. Given the sheer size of the global stock market, I recommend that a globally focused investor hold closer to 30 businesses at any given point in time. As an investor adds incremental companies to their portfolio, it dilutes their research efforts, adds trading costs, and increases the difficulty of monitoring the portfolio. Conversely, owning too few companies within a portfolio may cause the value of the portfolio to fluctuate more than necessary, tempting the investor to succumb to emotion and sell stocks at the wrong time and wrong price.

You Own a Conglomerate

Now picture yourself as the owner of a global business empire. Your business is comprised of the individual companies you have selectively purchased, and you can drill down to see the subcomponents and business lines of your new company. By investing in 20–30 good businesses, you have effectively built a conglomerate that generates revenue from numerous sectors, industries, and countries, providing more consistent sales and earnings power now and into the future. There will be times when some parts of your business empire will perform well while others may be weak. This is not necessarily bad or a sign of a poorly constructed portfolio, since it is difficult to predict which parts of your business empire will do well each year. If you had certainty, then you would divest the businesses that will underperform in the coming year and only hold those that will outperform. Looking at sources of revenue and earnings for your conglomerate, you can now assess how the fundamental earnings power of your company will fare in good and bad economic times. Is the combined business you built sufficiently diversified so that it captures significant areas of growth while still being able to endure weak economic times? Are the individual business components of your conglomerate reasonably valued, or are some of them overpriced and pose a risk to the overall portfolio?

Figures 20.1 and 20.2 illustrate the importance of owning a diversified group of businesses from differing industries. Since the earnings of companies in each industry group are affected by the same factors, owning several businesses in the same industry will not deliver the diversification benefits you are striving for. Figure 20.1 provides actual reported earnings from 20 large companies from around the world in differing industries. The mix of industries used in this fictitious portfolio is not meant to provide the reader with an investable portfolio but is intended only to highlight the need to diversify.

FIGURE 20.1 Annual EPS for 20 Large Global Companies (USD)

As an investor, it is important to stay focused on the combined earnings stream of your portfolio rather than share prices of individual securities or even the current market value of your portfolio. When you aggregate the earnings of all the companies in Figure 20.1, you achieve a more consistent stream of earnings in the same way a large, diversified conglomerate does. The dark line in Figure 20.2 shows how the average earnings per share (EPS) over a 10-year period was much more stable for the diversified portfolio of 20 large companies compared to a concentrated portfolio consisting of only the four financial companies (A, B, D, and L) in Figure 20.1.

Figure 20.2 shows that the diversified portfolio provided a more consistent level of earnings than did the concentrated portfolio and illustrates the importance of diversification to create a stable and growing stream of earnings. So long as earnings continue to rise, share prices will eventually follow. Remember from Chapter 6 that owning a basket of different currencies will also help create a more stable earnings stream.

FIGURE 20.2 Single-Sector versus Diversified Portfolio Average EPS

Data source: Bloomberg.

Stay Fully Invested

Even with everything we know about the possible warning signs of bull market peaks and bear market bottoms, timing the market has been an elusive goal for even the savviest professional investors around the world. Cash can significantly reduce portfolio returns when share prices are rising. For this reason, when I have raised cash to protect client capital, I ended up detracting value from the portfolio, with only a handful of exceptions. My preference therefore is to stay fully invested, always owning good businesses. Buy stocks for good times and bad, businesses that you think have sustainable earnings growth and are priced attractively. If a company becomes overvalued compared to its historical range, its sector, and the market, reassess why you own it and consider selling it and switching the proceeds into another stock. It is exceedingly difficult to time the market, but investors should always be prepared to sell companies with deteriorating fundamentals and redeploy the proceeds into good companies.

Saying Goodbye Is Always the Hardest Part

Buying a business can be relatively straightforward but knowing when to sell it can be extremely difficult. Valid reasons to sell a business include the loss of a key member of the management team, a significant increase in the competitiveness of the industry in which it operates, falling profit margins that cannot be reversed by management, or if valuation becomes expensive relative to the company's earnings prospects. In the case of a drop in earnings, the best way to think of it is as an owner of the business. Determine whether the earnings prospects of the company are permanently impaired or whether they will recover. If earnings are expected to recover, stay the course and hold on, or potentially add, to your position. As mentioned previously, another reason to sell a business is if the credit rating of the country in which the company is domiciled is downgraded below investment grade, or if you believe the geopolitical or currency risks are rising excessively in that country or region.

One helpful practice is to set an upper limit on the number of businesses owned. For example, if an investor were at their self-imposed maximum number of businesses (e.g., 25 or 30) and wanted to add a new holding, they would want to identify the weakest holding in their portfolio and sell it to make room for the new, better business. In this sense, active investors are best served by always looking for better investment opportunities, and I refer to the process as “high grading” the portfolio.

Rebalancing

Investors should also revisit their portfolio periodically and rebalance it. Since certain industries perform better or worse at various stages of the market cycle, the percentage weight of each company in your portfolio will fluctuate over time. It is best practice to reduce your winners and, assuming your investment thesis for them is still intact, add to your losing positions on an infrequent but regular basis. Most pension fund managers follow this procedure by shifting money from the best-performing asset classes or regions into those that have lagged. This technique is based on the idea that stocks, bonds, and other asset classes will revert to their long-term average valuations over time, a phenomenon known as mean reversion. Rebalancing forces you to buy low and sell high and can add tremendous value to your portfolio over the long run.

The frequency of rebalancing should depend partly on trading costs. If you pay a high commission rate for trades, then less frequent rebalancing is recommended. There is also something to be said for letting your winners run. Finding the right balance between letting your winners run and locking in profits can be tricky. For example, if you own 25 equally weighted stocks in your portfolio (i.e., 4% each), you may want to set a specific threshold at which you trim a position that has outperformed and reallocate the proceeds to stocks that have underperformed and whose relative weighting in your portfolio has fallen. In practice, if that threshold were, for example, 7%, when a stock rose above 7% of your portfolio you would reduce it back down to a 4% weight and add the proceeds of the sale to stocks that have lagged, bringing them back up to the original 4% weight. The decision on when and how to rebalance is yours. Optimal approaches to rebalancing typically involve employing a mechanical (unemotional) process. It is critical that you follow it precisely to prevent yourself from making random changes to your portfolio. If you find that your rebalancing process could be improved, make incremental adjustments while adhering to your existing plan, no matter how uncomfortable it may feel to do so at the time.

Tax may also play a role in your decision of when to rebalance your portfolio. If your portfolio is in a tax-sheltered account, there are no tax implications when you sell a security. However, since realized gains on the sale of a stock are usually subject to capital gains tax in an open (nonsheltered) account, investors should consider the tax implications when rebalancing their portfolio. My advice to investors is “do not let the tail wag the dog” when it comes to taxation. After all, paying tax means that you made money on your investment. I have seen investors delay the sale of a security purely for tax reasons, only to watch the security fall in value and their unrealized gain disappear completely. However, for transactions that would generate a particularly large taxable gain it would be best to consult a tax professional prior to executing the trade. In some cases, it may be better to sell the security over two or more taxation years.

As discussed in Chapter 5, signs of sector rotation and an assessment of where we are in the market cycle are a means to help improve your investment returns, but I would caution you that these should be considered over weeks and months rather than days. The shorter the time the more vulnerable the stock market is to random noise. A single day (or even week or month) of an apparent change in stock market leadership does not, in and of itself, confirm sector rotation or indicate an important inflection point in the market cycle. Bull market corrections and bear market rallies are notorious for fooling investors into thinking an inflection point has occurred when in fact the trend is still intact. Even if you can accurately identify sector rotation early enough to take advantage of it, it is simply not necessary to act on it if your portfolio has been appropriately constructed. If you own good businesses over a long time period, you should be able to generate sufficient wealth to fund your retirement needs. This means generating solid returns by diminishing the impact of negative performance through diversification, maximizing long-run success by choosing good companies, staying fully invested, and rebalancing to take advantage of reversion to the mean for your good companies.

Advanced Investment Strategies

The basic premise behind this book is that one can create a portfolio of great businesses that will perform well over a full market cycle, through both good and bad times. There are some investment strategies, however, that may be appropriate for more experienced investors who are able to devote the time necessary to monitor the markets continually. One such strategy could be to create two baskets of great businesses, one for good economic times and one for bad economic times. To illustrate the concept, I created two hypothetical portfolios based on sector returns only; therefore, no individual stocks were chosen. The market sectors are broken into two groups: cyclical and noncyclical. The cyclical sectors are more sensitive to economic growth and include consumer discretionary, energy, financials, industrials, materials, and technology. The noncyclical sectors are less sensitive to economic growth and include consumer staples, telecom, healthcare, and utilities. Real estate is excluded here because it was only recently broken out as a separate sector of the stock market and so historical data is limited.

Next, I created two portfolios, simply allocating between the cyclical and noncyclical sectors using an 80/20 split, as shown in Figure 20.3.

In Figure 20.4, Portfolio A is our “offensive” portfolio and is built for strong economic growth and bull markets, while Portfolio B is our “defensive” portfolio and is built for recessions and bear markets. Note that the securities do not change when we switch between the two portfolios, only the amount we invest in each of them.

In this example, the decision of which portfolio to own at any point in time is simple. First, choose a broad stock market index that is most reflective of your portfolio. If the stock market index is trading above its 18-month moving average, you own the offensive portfolio (Portfolio A), and if it is trading below the 18-month moving average, you own the defensive portfolio (Portfolio B). The 18-month moving average is the average month-end closing price for the index for the preceding 18 months. The benefit of this type of rebalancing approach is its simplicity since anyone can easily calculate and track the moving average of a broad market index. Moving averages can often be added easily on a price chart, depending on the service provider. I have found that the 18-month moving average provides a relatively consistent level of support for a bull market (and therefore can act as an effective trigger point for when to switch between an offensive and defensive posture), but there are no guarantees it will work in the future. Accordingly, investors may be best served by using a long-term moving average (like the 18-month moving average) in conjunction with the signs described in Chapter 5 that have been known to provide an early warning sign for bear market bottoms and bull market tops.

FIGURE 20.3 Sample Cyclical versus Noncyclical Sector Portfolios

FIGURE 20.4 Sample Offensive and Defensive Portfolio Sector Weights

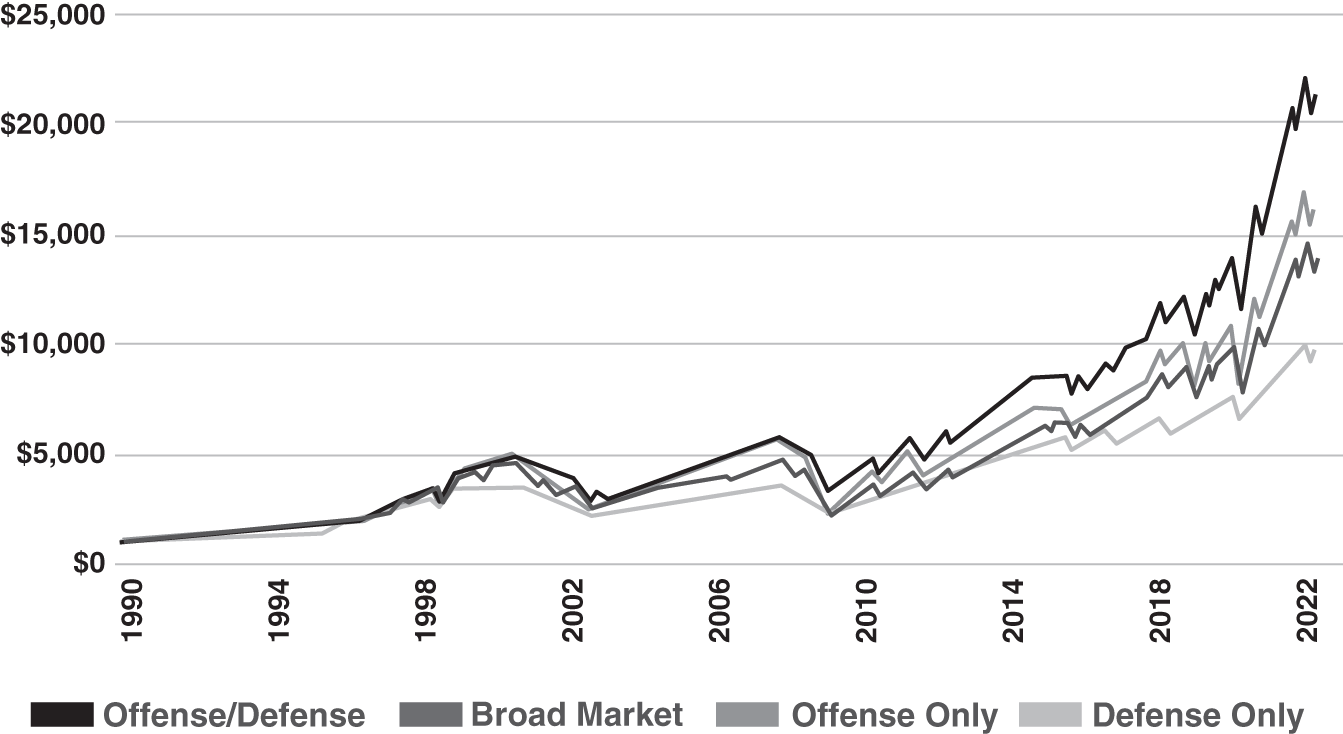

The results of an approach as simplistic as this may surprise you. Merely rebalancing between our offensive and defensive portfolios can add significant value over a buy-and-hold strategy. Figure 20.5 shows the value of $1,000 invested at the beginning of 1990 under each scenario, namely reallocating between offensive and defensive portfolios versus simply holding the broad market index.

FIGURE 20.5 Playing Offense/Defense

In this example, owning the broad stock market from the beginning of 1990 to March 2022 would have generated an ending portfolio value of $13,767. Compared to the broad stock market, the defensive portfolio generated a lower return, with an ending value of $9,691, while the offensive portfolio generated a higher return, with an ending value of $15,994. These results make sense when we consider the fact that despite interim recessions and bear markets, economic growth and equity markets for the full period were both strong.

What is most interesting, though, is when we adjust our weights between the offensive and defensive portfolios in the manner just described. The straightforward process of rebalancing our weights between Portfolio A and Portfolio B based solely on whether the broad stock market traded above or below its 18-month moving average resulted in an ending portfolio value of $21,279. That amounts to a 54% higher portfolio value over 30 years compared to passively owning the broad market. Although these results do ignore trading costs (which would reduce the strategy's return), investors should be able to offset these costs by selecting good businesses since the offensive and defensive portfolios are based only on passive sector returns. Furthermore, while this example is based on price appreciation only, dividends are likely to augment the effectiveness of this strategy since dividend-paying stocks tend to perform better in bear markets from a total return perspective. Keep in mind, though, that these results are based on a single time frame and a single stock market and that the results will vary based on the time period and index chosen. Nevertheless, this helps to illustrate how an investor can generate superior returns and provide some downside protection for their portfolios when stock prices fall while remaining fully invested throughout the market cycle.

Admittedly, dividing sectors into cyclical and defensive (noncyclical) groups is an oversimplification. Cyclical sectors contain businesses that could be considered defensive, and defensive sectors contain businesses that could be considered cyclical. You can also think of your businesses in terms of being low-beta (noncyclical) or high-beta (cyclical). As an investor, you should therefore consider how the stocks you own will behave in a given market environment and in each stage of the market cycle. Similar to the previous sector-based example, investors could therefore rebalance a portfolio of individual stocks using a moving average or some other mix of indicators. When you believe that market risks are elevated based on the criteria set out in Chapter 5, or otherwise decide to get defensive, reduce the weights of stocks that are cyclical or high-beta, and move the proceeds to your low-beta, defensive stocks. Conversely, if you believe a bear market bottom has been reached, reduce weights in defensive stocks and add to the cyclical, higher-beta stocks.

In a similar fashion, I created offensive and defensive portfolios, each made up of 25 equally weighted large, global stocks. All 50 stocks were randomly chosen from a pool of stocks that I regard as good businesses and that have remained attractively valued. The defensive portfolio consisted of stocks in the communication services, consumer staples, healthcare, real estate, and utilities sectors, while the offensive portfolio consisted of businesses primarily in the technology, industrials, energy, materials, financials, and consumer discretionary sectors. From the end of 1999 to the end of April 2022, and with no rebalancing, the offensive portfolio returned 12.5% annually while the defensive portfolio was not far behind, generating a 12.2% annual return. This suggests that it is most important to own good businesses and stay fully invested, regardless of whether you are positioned for a bull or bear market. Keep in mind that, while you can add value by being incrementally more defensive in a bear market and offensive in a bull market, you can also reduce your returns significantly if you time these changes poorly.

Advanced Portfolio Structures

The way we have structured our portfolio, buying a diverse group of good businesses, is known as a “long-only” investment strategy and the stocks you own are referred to as long positions. As you become comfortable with the process of building and rebalancing portfolios, and your understanding of the global financial markets grows, you may want to consider a more advanced form of portfolio structure, known as a “long-short” strategy. The benefit of a long-short strategy over a long-only strategy is improved risk management through the addition of short selling. Recall that a short seller is an investor who borrows shares in a company and sells them, with the intention of buying them back later in the future at a lower price and then returning the borrowed shares. The short seller thinks that the price of the stock today is too high and that it will fall soon. Long-short strategies are particularly useful in bull market corrections and in bear markets when stock prices are falling, since gains in the short positions will help offset losses in the long positions. Be aware that in order for you to short-sell a stock, you need to borrow the stock first through a broker. To do so you must provide collateral (usually in the form of your long positions) and you must pay the owner of the shares interest based on a borrow rate to compensate them for loaning you the shares.

There are numerous ways to structure a long-short portfolio. Hedge funds and market-neutral funds are both variations of the long-short strategy. You may have also heard of a “130/30” fund, which refers to a portfolio that is 130% long and 30% short. In this case, the investor short-sells stocks that total 30% of the portfolio's value and then uses the proceeds of those sales to add to the “long” portion of the portfolio. The expectation is that the short positions will fall in value while the long positions will increase in value. For example, using the shares they own as collateral, an investor with a $1,000,000 portfolio could short-sell $300,000 worth of shares of businesses they dislike and use the $300,000 cash proceeds to add to their existing long positions. The investor is now long $1,300,000 in stock but short $300,000, so the net long position (total market exposure) is still $1,000,000. Numerous studies have been done to compare the efficacy of long-short strategies, and these often indicate that a long-short strategy such as this will provide superior, long-term risk-adjusted returns compared to long-only strategies.

Short selling, especially when done using individual company stocks, is not for the faint of heart. Volatility in a single stock can be remarkably high and cause significant, even unlimited, losses for anyone who is short the stock. In addition, short selling requires a different skill set from long-only investing. One way to capture the benefits of short selling without the risk of shorting the shares of individual companies is to short index or sector-based ETFs. By shorting broad market ETFs, investors are essentially reducing the market risk (beta) in their portfolio. If the investor is unable to short stocks in their investment account, there are a number of inverse index ETFs that can be purchased “long” that provide the same benefit of a short position because they move in the opposite direction from the index. One limitation of buying inverse ETFs, however, is that there are no short sale proceeds that can be used to add to your individual long positions.

There are many approaches to portfolio construction beyond what has been outlined here. Regardless of the approach you choose, your investment decisions should be based on careful analysis of the businesses purchased, including how the earnings profiles of those companies are affected by different stages of the economic cycle, and how their share prices will move relative to one another (correlation) and the broad market (beta) during the market cycle.