What Most People Get Wrong About Men and Women

by Catherine H. Tinsley and Robin J. Ely

THE CONVERSATION ABOUT THE TREATMENT of women in the workplace has reached a crescendo of late, and senior leaders—men as well as women—are increasingly vocal about a commitment to gender parity. That’s all well and good, but there’s an important catch. The discussions, and many of the initiatives companies have undertaken, too often reflect a faulty belief: that men and women are fundamentally different, by virtue of their genes or their upbringing or both. Of course, there are biological differences. But those are not the differences people are usually talking about. Instead, the rhetoric focuses on the idea that women are inherently unlike men in terms of disposition, attitudes, and behaviors. (Think headlines that tout “Why women do X at the office” or “Working women don’t Y.”)

One set of assumed differences is marshaled to explain women’s failure to achieve parity with men: Women negotiate poorly, lack confidence, are too risk-averse, or don’t put in the requisite hours at work because they value family more than their careers. Simultaneously, other assumed differences—that women are more caring, cooperative, or mission-driven—are used as a rationale for companies to invest in women’s success. But whether framed as a barrier or a benefit, these beliefs hold women back. We will not level the playing field so long as the bedrock on which it rests is our conviction about how the sexes are different.

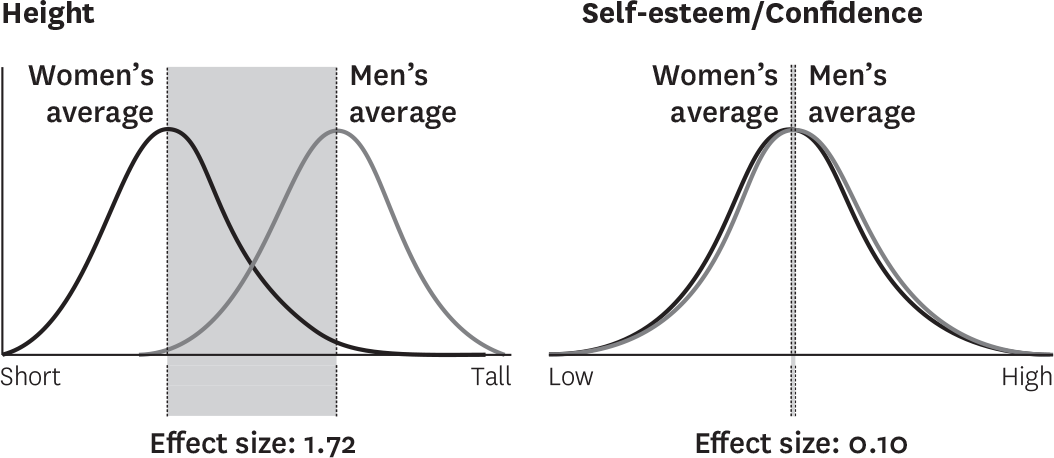

The reason is simple: Science, by and large, does not actually support these claims. There is wide variation among women and among men, and meta-analyses show that, on average, the sexes are far more similar in their inclinations, attitudes, and skills than popular opinion would have us believe. We do see sex differences in various settings, including the workplace—but those differences are not rooted in fixed gender traits. Rather, they stem from organizational structures, company practices, and patterns of interaction that position men and women differently, creating systematically different experiences for them. When facing dissimilar circumstances, people respond differently—not because of their sex but because of their situations.

Emphasizing sex differences runs the risk of making them seem natural and inevitable. As anecdotes that align with stereotypes are told and retold, without addressing why and when stereotypical behaviors appear, sex differences are exaggerated and take on a determinative quality. Well-meaning but largely ineffectual interventions then focus on “fixing” women or accommodating them rather than on changing the circumstances that gave rise to different behaviors in the first place.

Take, for example, the common belief that women are more committed to family than men are. Research simply does not support that notion. In a study of Harvard Business School graduates that one of us conducted, nearly everyone, regardless of gender, placed a higher value on their families than on their work (see “Rethink What You ‘Know’ About High-Achieving Women,” HBR, December 2014). Moreover, having made career decisions to accommodate family responsibilities didn’t explain the gender achievement gap. Other research, too, makes it clear that men and women do not have fundamentally different priorities.

Numerous studies show that what does differ is the treatment mothers and fathers receive when they start a family. Women (but not men) are seen as needing support, whereas men are more likely to get the message—either explicit or subtle—that they need to “man up” and not voice stress and fatigue. If men do ask, say, for a lighter travel schedule, their supervisors may cut them some slack—but often grudgingly and with the clear expectation that the reprieve is temporary. Accordingly, some men attempt an under-the-radar approach, quietly reducing hours or travel and hoping it goes unnoticed, while others simply concede, limiting the time they spend on family responsibilities and doubling down at work. Either way, they maintain a reputation that keeps them on an upward trajectory. Meanwhile, mothers are often expected, indeed encouraged, to ratchet back at work. They are rerouted into less taxing roles and given less “demanding” (read: lower-status, less career-enhancing) clients.

To sum up, men’s and women’s desires and challenges about work/family balance are remarkably similar. It is what they experience at work once they become parents that puts them in very different places.

Things don’t have to be this way. When companies observe differences in the overall success rates of women and men, or in behaviors that are critical to effectiveness, they can actively seek to understand the organizational conditions that might be responsible, and then they can experiment with changing those conditions.

Consider the example of a savvy managing director concerned about the leaky pipeline at her professional services firm. Skeptical that women were simply “opting out” following the birth of a child, she investigated and found that one reason women were leaving the firm stemmed from the performance appraisal system: Supervisors had to adhere to a forced distribution when rating their direct reports, and women who had taken parental leave were unlikely to receive the highest rating because their performance was ranked against that of peers who had worked a full year. Getting less than top marks not only hurt their chances of promotion but also sent a demoralizing message that being a mother was incompatible with being on a partner track. However, the fix was relatively easy: The company decided to reserve the forced distribution for employees who worked the full year, while those with long leaves could roll over their rating from the prior year. That applied to both men and women, but the policy was most heavily used by new mothers. The change gave women more incentive to return from maternity leave and helped keep them on track for advancement. Having more mothers stay on track, in turn, helped chip away at assumptions within the firm about women’s work/family preferences.

As this example reveals, companies need to dive deeper into their beliefs, norms, practices, and policies to understand how they position women relative to men and how the different positions fuel inequality. Seriously investigating the context that gives rise to differential patterns in the way men and women experience the workplace—and intervening accordingly—can help companies chart a path to gender parity.

Below, we address three popular myths about how the sexes differ and explain how each manifests itself in organizational discourse about women’s lagged advancement. Drawing on years of social science research, we debunk the myths and offer alternative explanations for observed sex differences—explanations that point to ways that managers can level the playing field. We then offer a four-pronged strategy for undertaking such actions.

Popular Myths

We’ve all heard statements in the media and in companies that women lack the desire or ability to negotiate, that they lack confidence, and that they lack an appetite for risk. And, the thinking goes, those shortcomings explain why women have so far failed to reach parity with men.

For decades, studies have examined sex differences on these three dimensions, enabling social scientists to conduct meta-analyses—investigations that reveal whether or not, on average across studies, sex differences hold, and if so, how large the differences are. (See the sidebar “The Power of Meta-Analysis.”) Just as importantly, meta-analyses also reveal the circumstances under which differences between men and women are more or less likely to arise. The aggregated findings are clear: Context explains any sex differences that exist in the workplace.

Take negotiation. Over and over, we hear that women are poor negotiators—they “settle too easily,” are “too nice,” or are “too cooperative.” But not so, according to research. Jens Mazei and colleagues recently analyzed more than 100 studies examining whether men and women negotiate different outcomes; they determined that gender differences were small to negligible. Men have a slight advantage in negotiations when they are advocating exclusively for themselves and when ambiguity about the stakes or opportunities is high. Larger disparities in outcomes occur when negotiators either have no prior experience or are forced to negotiate, as in a mandated training exercise. But such situations are atypical, and even when they do arise, statisticians would deem the resulting sex differences to be small. As for the notion that women are more cooperative than men, research by Daniel Balliet and colleagues refutes that.

The belief that women lack confidence is another fallacy. That assertion is commonly invoked to explain why women speak up less in meetings and do not put themselves forward for promotions unless they are 100% certain they meet all the job requirements. But research does not corroborate the idea that women are less confident than men. Analyzing more than 200 studies, Kristen Kling and colleagues concluded that the only noticeable differences occurred during adolescence; starting at age 23, differences become negligible.

What about risk taking—are women really more conservative than men? Many people believe that’s true—though they are split on whether being risk-averse is a strength or a weakness. On the positive side, the thinking goes, women are less likely to get caught up in macho displays of bluff and bravado and thus are less likely to take unnecessary risks. Consider the oft-heard sentiment following the demise of Lehman Brothers: “If Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters, the financial crisis might have been averted.” On the negative side, women are judged as too cautious to make high-risk, potentially high-payoff investments.

But once again, research fails to support either of these stereotypes. As with negotiation, sex differences in the propensity to take risks are small and depend on the context. In a meta-analysis performed by James Byrnes and colleagues, the largest differences arise in contexts unlikely to exist in most organizations (such as among people asked to participate in a game of pure chance). Similarly, in a study Peggy Dwyer and colleagues ran examining the largest, last, and riskiest investments made by nearly 2,000 mutual fund investors, sex differences were very small. More importantly, when investors’ specific knowledge about the investments was added to the equation, the sex difference diminished to near extinction, suggesting that access to information, not propensity for risk taking, explains the small sex differences that have been documented.

In short, a wealth of evidence contradicts each of these popular myths. Yet they live on through oft-repeated narratives routinely invoked to explain women’s lagged advancement.

More-Plausible Explanations

The extent to which employees are able to thrive and succeed at work depends partly on the kinds of opportunities and treatment they receive. People are more likely to behave in ways that undermine their chances for success when they are disconnected from information networks, when they are judged or penalized disproportionately harshly for mistakes or failures, and when they lack feedback. Unfortunately, women are more likely than men to encounter each of these situations. And the way they respond—whether that’s by failing to drive a hard bargain, to speak up, or to take risks—gets unfairly attributed to “the way women are,” when in fact the culprit is very likely the differential conditions they face.

Multiple studies show, for example, that women are less embedded in networks that offer opportunities to gather vital information and garner support. When people lack access to useful contacts and information, they face a disadvantage in negotiations. They may not know what is on the table, what is within the realm of possibility, or even that a chance to strike a deal exists. When operating under such conditions, women are more likely to conform to the gender stereotype that “women don’t ask.”

We saw this dynamic vividly play out when comparing the experiences of two professionals we’ll call Mary and Rick. (In this example and others that follow, we have changed the names and some details to maintain confidentiality.) Mary and Rick were both midlevel advisers in the wealth management division of a financial services firm. Rick was able to bring in more assets to manage because he sat on the board of a nonprofit, giving him access to a pool of potential clients with high net worth. What Mary did not know for many years is how Rick had gained that advantage. Through casual conversations with one of the firm’s senior partners, with whom he regularly played tennis, Rick had learned that discretionary funds existed to help advisers cultivate relationships with clients. So he arranged for the firm to make a donation to the nonprofit. He then began attending the nonprofit’s fund-raising events and hobnobbing with key players, eventually parlaying his connections into a seat on the board. Mary, by contrast, had no informal relationships with senior partners at the firm and no knowledge of the level of resources that could have helped her land clients.

When people are less embedded, they are also less aware of opportunities for stretch assignments and promotions, and their supervisors may be in the dark about their ambitions. But when women fail to “lean in” and seek growth opportunities, it is easy to assume that they lack the confidence to do so—not that they lack pertinent information. Julie’s experience is illustrative. Currently the CEO of a major investment fund, Julie had left her previous employer of 15 years after learning that a more junior male colleague had leapfrogged over her to fill an opening she didn’t even know existed. When she announced that she was leaving and why, her boss was surprised. He told her that if he had realized she wanted to move up, he would have gladly helped position her for the promotion. But because she hadn’t put her hat in the ring, he had assumed she lacked confidence in her ability to handle the job.

How people react to someone’s mistake or failure can also affect that person’s ability to thrive and succeed. Several studies have found that because women operate under a higher-resolution microscope than their male counterparts do, their mistakes and failures are scrutinized more carefully and punished more severely. People who are scrutinized more carefully will, in turn, be less likely to speak up in meetings, particularly if they feel no one has their back. However, when women fail to speak up, it is commonly assumed that they lack confidence in their ideas.

We saw a classic example of this dynamic at a biotech company in which team leaders noticed that their female colleagues, all highly qualified research scientists, participated far less in team meetings than their male counterparts did, yet later, in one-on-one conversations, often offered insightful ideas germane to the discussion. What these leaders had failed to see was that when women did speak in meetings, their ideas tended to be either ignored until a man restated them or shot down quickly if they contained even the slightest flaw. In contrast, when men’s ideas were flawed, the meritorious elements were salvaged. Women therefore felt they needed to be 110% sure of their ideas before they would venture to share them. In a context in which being smart was the coin of the realm, it seemed better to remain silent than to have one’s ideas repeatedly dismissed.

It stands to reason that people whose missteps are more likely to be held against them will also be less likely to take risks. That was the case at a Big Four accounting firm that asked us to investigate why so few women partners were in formal leadership roles. The reason, many believed, was that women did not want such roles because of their family responsibilities, but our survey revealed a more complex story. First, women and men were equally likely to say they would accept a leadership role if offered one, but men were nearly 50% more likely to have been offered one. Second, women were more likely than men to say that worries about jeopardizing their careers deterred them from pursuing leadership positions—they feared they would not recover from failure and thus could not afford to take the risks an effective leader would need to take. Research confirms that such concerns are valid. For example, studies by Victoria Brescoll and colleagues found that if women in male-dominated occupations make mistakes, they are accorded less status and seen as less competent than men making the same mistakes; a study by Ashleigh Rosette and Robert Livingston demonstrated that black women leaders are especially vulnerable to this bias.

Research also shows that women get less frequent and lower-quality feedback than men. When people don’t receive feedback, they are less likely to know their worth in negotiations. Moreover, people who receive little feedback are ill-equipped to assess their strengths, shore up their weaknesses, and judge their prospects for success and are therefore less able to build the confidence they need to proactively seek promotions or make risky decisions.

An example of this dynamic comes from a consulting firm in which HR staff members delivered partners’ annual feedback to associates. The HR folks noticed that when women were told they were “doing fine,” they “freaked out,” feeling damned by faint praise; when men received the same feedback, they left the meeting “feeling great.” HR concluded that women lack self-confidence and are therefore more sensitive to feedback, so the team advised partners to be especially encouraging to the women associates and to soften any criticism. Many of the partners were none too pleased to have to treat a subset of their associates with kid gloves, grousing that “if women can’t stand the heat, they should get out of the kitchen.” What these partners failed to realize, however, is that the kitchen was a lot hotter for women in the firm than for men. Why? Because the partners felt more comfortable with the men and so were systematically giving them more informal, day-to-day feedback. When women heard in their annual review that they were doing “fine,” it was often the first feedback they’d received all year; they had nothing else to go on and assumed it meant their performance was merely adequate. In contrast, when men heard they were doing “fine,” it was but one piece of information amidst a steady stream. The upshot was disproportionate turnover among women associates, many of whom left the firm because they believed their prospects for promotion were slim.

An Alternative Approach

The problem with the sex-difference narrative is that it leads companies to put resources into “fixing” women, which means that women miss out on what they need—and what every employee deserves: a context that enables them to reach their potential and maximizes their chances to succeed.

Managers who are advancing gender equity in their firms are taking a more inquisitive approach—rejecting old scripts, seeking an evidence-based understanding of how women experience the workplace, and then creating the conditions that increase women’s prospects for success. Their approach entails four steps:

1. Question the narrative

A consulting firm we worked with had recruited significant numbers of talented women into its entry ranks—and then struggled to promote them. Their supervisors’ explanations? Women are insufficiently competitive, lack “fire in the belly,” or don’t have the requisite confidence to excel in the job. But those narratives did not ring true to Sarah, a regional head, because a handful of women—those within her region—were performing and advancing at par. So rather than accept her colleagues’ explanations, she got curious.

2. Generate a plausible alternative explanation

Sarah investigated the factors that might have helped women in her region succeed and found that they received more hands-on training and more attention from supervisors than did women in other regions. This finding suggested that the problem lay not with women’s deficiencies but with their differential access to the conditions that enhance self-confidence and success.

To test that hypothesis, Sarah designed an experiment, with our help. First, we randomly split 60 supervisors into two groups of 30 for a training session on coaching junior consultants. Trainers gave both groups the same lecture on how to be a good coach. With one group, however, trainers shared research showing that differences in men’s and women’s self-confidence are minuscule, thus subtly giving the members of this “treatment” group reason to question gender stereotypes. The “control” group didn’t get that information. Next, trainers gave all participants a series of hypotheticals in which an employee—sometimes a man and sometimes a woman—was underperforming. In both groups, participants were asked to write down the feedback they would give the underperforming employee.

Clear differences emerged between the two groups. Supervisors in the control group took different tacks with the underperforming man and woman: They were far less critical of the woman and focused largely on making her feel good, whereas they gave the man feedback that was more direct, specific, and critical, often with concrete suggestions for how he could improve. In contrast, the supervisors who had been shown research that refuted sex differences in self-confidence gave both employees the same kind of feedback; they also asked for more-granular information about the employee’s performance so that they could deliver constructive comments. We were struck by how the participants who had been given a reason to question gender stereotypes focused on learning more about individuals’ specific performance problems.

The experiment confirmed Sarah’s sense that women’s lagged advancement might be due at least partly to supervisors’ assumptions about the training and development needs of their female direct reports. Moreover, her findings gave supervisors a plausible alternative explanation for women’s lagged advancement—a necessary precondition for taking the next step. Although different firms find different types of evidence more or less compelling—not all require as rigorous a test as this firm did—Sarah’s evidence-based approach illustrates a key part of the strategy we are advocating.

3. Change the context and assess the results

Once a plausible alternative explanation has been developed, companies can make appropriate changes and see if performance improves. Two stories help illustrate this step. Both come from a midmarket private equity firm that was trying to address a problem that had persisted for 10 years: The company’s promotion and retention rates for white women and people of color were far lower than its hiring rates.

The first story involves Elaine, an Asian-American senior associate who wanted to sharpen her financing skills and asked Dave, a partner, if she could assist with that aspect of his next deal. He invited her to lunch, but when they met, he was underwhelmed. Elaine struck him as insufficiently assertive and overly cautious. He decided against putting her on his team—but then he had second thoughts. The partners had been questioning their ability to spot and develop talent, especially in the case of associates who didn’t look like them. Dave thus decided to try an experiment: He invited Elaine to join the team and then made a conscious effort to treat her exactly as he would have treated someone he deemed a superstar. He introduced her to the relevant players in the industry, told the banks she would be leading the financing, and gave her lots of rope but also enough feedback and coaching so that she wouldn’t hang herself. Elaine did not disappoint; indeed, her performance was stellar. While quiet in demeanor, Dave’s new protégée showed an uncanny ability to read the client and come up with creative approaches to the deal’s financing.

A second example involves Ned, a partner who was frustrated that Joan, a recent-MBA hire on his team, didn’t assert herself on management team calls. At first Ned simply assumed that Joan lacked confidence. But then it occurred to him that he might be falling back on gender stereotypes, and he took a closer look at his own behavior. He realized that he wasn’t doing anything to make participation easier for her and was actually doing things that made it harder, like taking up all the airtime on calls. So they talked about it, and Joan admitted that she was afraid of making a mistake and was hyperaware that if she spoke, she needed to say something very smart. Ned realized that he, too, was afraid she would make a mistake or wouldn’t add value to the discussion, which is partly why he took over. But on reflection, he saw that it wouldn’t be the end of the world if she did stumble—he did the same himself now and again. For their next few calls, they went over the agenda beforehand and worked out which parts she would take the lead on; he then gave her feedback after the call. Ned now has a junior colleague to whom he can delegate more; Joan, meanwhile, feels more confident and has learned that she can take risks and recover from mistakes.

4. Promote continual learning

Both Dave and Ned recognized that their tendency to jump to conclusions based on stereotypes was robbing them—and the firm—of vital talent. Moreover, they have seen firsthand how questioning assumptions and proactively changing conditions gives women the opportunity to develop and shine. The lessons from these small-scale experiments are ongoing: Partners at the firm now meet regularly to discuss what they’re learning. They also hold one another accountable for questioning and testing gender-stereotypical assessments as they arise. As a result, old narratives about women’s limitations are beginning to give way to new narratives about how the firm can better support all employees.

![]()

The four steps we’ve outlined are consistent with research suggesting that on difficult issues such as gender and race, managers respond more positively when they see themselves as part of the solution rather than simply part of the problem. The solution to women’s lagged advancement is not to fix women or their managers but to fix the conditions that undermine women and reinforce gender stereotypes. Furthermore, by taking an inquisitive, evidence-based approach to understanding behavior, companies can not only address gender disparities but also cultivate a learning orientation and a culture that gives all employees the opportunity to reach their full potential.

Originally published in May–June 2018. Reprint R1803J