How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Companies

by Michael E. Porter and James E. Heppelmann

THE EVOLUTION OF PRODUCTS into intelligent, connected devices—which are increasingly embedded in broader systems—is radically reshaping companies and competition.

Smart thermostats control a growing array of home devices, transmitting data about their use back to manufacturers. Intelligent, networked industrial machines autonomously coordinate and optimize work. Cars stream data about their operation, location, and environment to their makers and receive software upgrades that enhance their performance or head off problems before they occur. Products continue to evolve long after entering service. The relationship a firm has with its products—and with its customers—is becoming continuous and open-ended.

In our previous HBR article, “How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Competition” (November 2014), we examined the implications external to the firm, looking in detail at how smart, connected products affect rivalry, industry structure, industry boundaries, and strategy. (See the sidebar “Implications for Strategy.”) In this article we’ll explore their internal implications: how the nature of smart, connected products substantially changes the work of virtually every function within the manufacturing firm. The core functions—product development, IT, manufacturing, logistics, marketing, sales, and after-sale service—are being redefined, and the intensity of coordination among them is increasing. Entirely new functions are emerging, including those to manage the staggering quantities of data now available. All of this has major implications for the classic organizational structure of manufacturers. What is under way is perhaps the most substantial change in the manufacturing firm since the Second Industrial Revolution, more than a century ago.

The New Product Capabilities

To fully grasp how smart, connected products are changing how companies work, we must first understand their inherent components, technology, and capabilities—something that our previous article examined. To recap:

All smart, connected products, from home appliances to industrial equipment, share three core elements: physical components (such as mechanical and electrical parts); smart components (sensors, microprocessors, data storage, controls, software, an embedded operating system, and a digital user interface); and connectivity components (ports, antennae, protocols, and networks that enable communication between the product and the product cloud, which runs on remote servers and contains the product’s external operating system).

Smart, connected products require a whole new supporting technology infrastructure. This “technology stack” provides a gateway for data exchange between the product and the user and integrates data from business systems, external sources, and other related products. The technology stack also serves as the platform for data storage and analytics, runs applications, and safeguards access to products and the data flowing to and from them. (See the exhibit “The new technology stack.”)

Smart, connected products require companies to build and support an entirely new technology infrastructure. This “technology stack” is made up of multiple layers, including new product hardware, embedded software, connectivity, a product cloud consisting of software running on remote servers, a suite of security tools, a gateway for external information sources, and integration with enterprise business systems.

Source: “How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Competition,” Harvard Business Review, November 2014

This infrastructure enables extraordinary new product capabilities. First, products can monitor and report on their own condition and environment, helping to generate previously unavailable insights into their performance and use. Second, complex product operations can be controlled by the users, through numerous remote-access options. That gives users the unprecedented ability to customize the function, performance, and interface of products and to operate them in hazardous or hard-to-reach environments.

Third, the combination of monitoring data and remote-control capability creates new opportunities for optimization. Algorithms can substantially improve product performance, utilization, and uptime, and how products work with related products in broader systems, such as smart buildings and smart farms. Fourth, the combination of monitoring data, remote control, and optimization algorithms allows autonomy. Products can learn, adapt to the environment and to user preferences, service themselves, and operate on their own.

Reshaping the Manufacturing Company

To create products and get them to customers, manufacturers perform a wide range of activities, which generally take place in a standard set of functional units: research and development (or engineering), IT, manufacturing, logistics, marketing, sales, after-sale service, human resources, procurement, and finance. The new capabilities of smart, connected products alter every activity in this value chain. At the core of what is reshaping the value chain is data.

The new data resource

Before products became smart and connected, data was generated primarily by internal operations and through transactions across the value chain—order processing, interactions with suppliers, sales interactions, customer service visits, and so on. Firms supplemented that data with information gathered from surveys, research, and other external sources. By combining the data, companies knew something about customers, demand, and costs—but much less about the functioning of products. The responsibility for defining and analyzing data tended to be decentralized within functions and siloed. Though functions shared data (sales data, for example, might be used to manage service parts inventory), they did so on a limited, episodic basis.

Now, for the first time, these traditional sources of data are being supplemented by another source—the product itself. Smart, connected products can generate real-time readings that are unprecedented in their variety and volume. Data now stands on par with people, technology, and capital as a core asset of the corporation and in many businesses is perhaps becoming the decisive asset.

This new product data is valuable by itself, yet its value increases exponentially when it is integrated with other data, such as service histories, inventory locations, commodity prices, and traffic patterns. In a farm setting, data from humidity sensors can be combined with weather forecasts to optimize irrigation equipment and reduce water use. In fleets of vehicles, information about the pending service needs of each car or truck, and its location, allows service departments to stage parts, schedule maintenance, and increase the efficiency of repairs. Data on warranty status becomes more valuable when combined with data on product use and performance. Knowing that a customer’s heavy use of a product is likely to result in a premature failure covered under warranty, for example, can trigger preemptive service that may preclude later costly repairs.

Data analytics

As the ability to unlock the full value of data becomes a key source of competitive advantage, the management, governance, analysis, and security of that data is developing into a major new business function.

While individual sensor readings are valuable, companies often can unearth powerful insights by identifying patterns in thousands of readings from many products over time. For example, information from disparate individual sensors, such as a car’s engine temperature, throttle position, and fuel consumption, can reveal how performance correlates with the car’s engineering specifications. Linking combinations of readings to the occurrence of problems can be useful, and even when the root cause of a problem is hard to deduce, those patterns can be acted on. Data from sensors that measure heat and vibration, for example, can predict an impending bearing failure days or weeks in advance. Capturing such insights is the domain of big data analytics, which blend mathematics, computer science, and business analysis techniques.

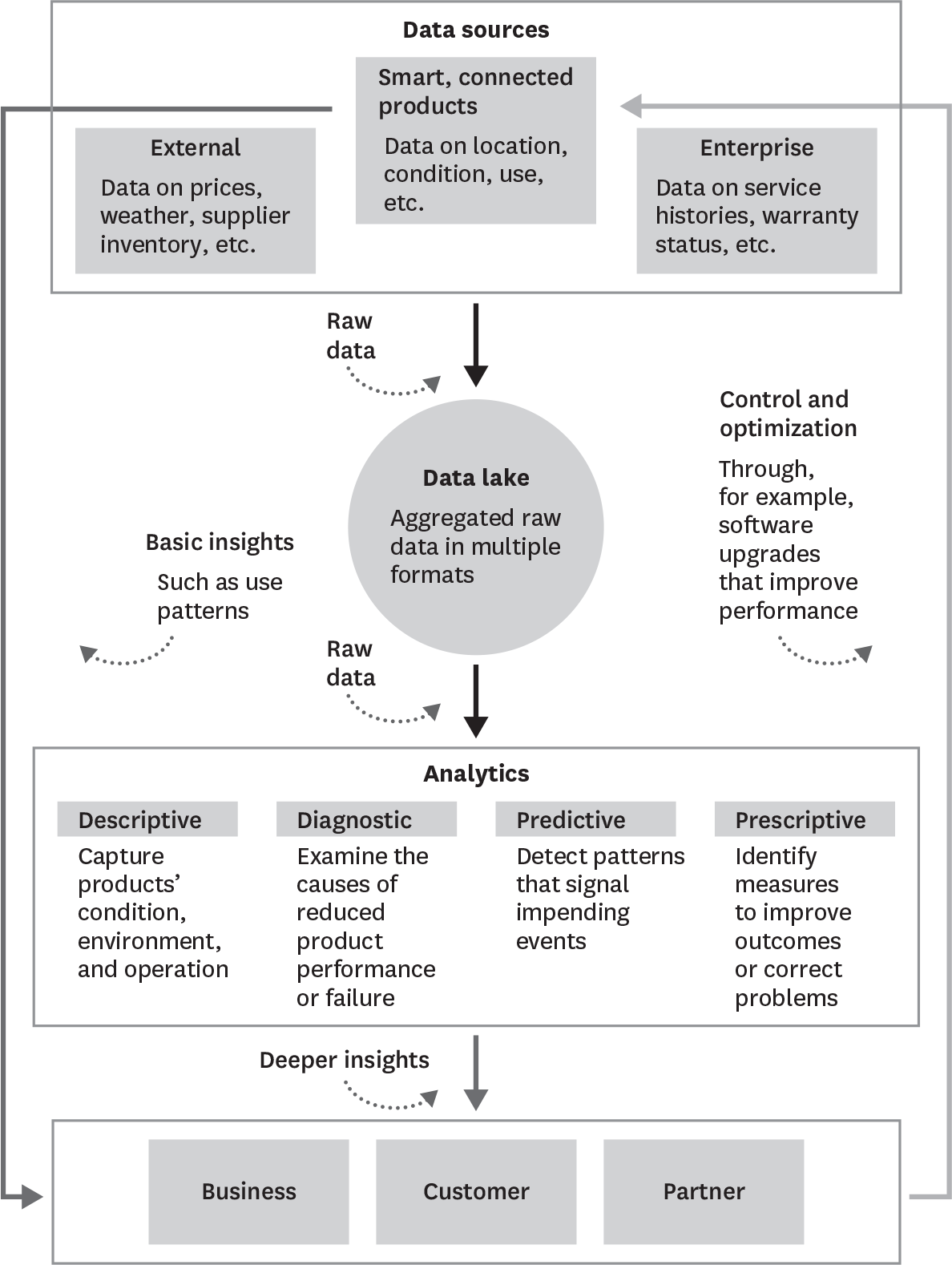

Big data analytics employ a family of new techniques to understand those patterns. A challenge is that the data from smart, connected products and related internal and external data are often unstructured. They may be in an array of formats, such as sensor readings, locations, temperatures, and sales and warranty history. Conventional approaches to data aggregation and analysis, such as spreadsheets and database tables, are ill-suited to managing a wide variety of data formats. The emerging solution is a “data lake,” a repository in which disparate data streams can be stored in their native formats. From there, the data can be studied with a set of new data analytics tools. Those tools fall into four categories: descriptive, diagnostic, predictive, and prescriptive. (For more details, see the exhibit “Creating new value with data.”)

Data from smart, connected products is generating insights that help businesses, customers, and partners optimize product performance. Simple analytics, applied by individual products to their own data, reveal basic insights; more-sophisticated analytics, applied to product data that has been pooled into a “lake” with data from external and enterprise sources, unearth deeper insights.

To better understand the rich data generated by smart, connected products, companies are also beginning to deploy a tool called a “digital twin.” Originally conceived by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), a digital twin is a 3-D virtual-reality replica of a physical product. As data streams in, the twin evolves to reflect how the physical product has been altered and used and the environmental conditions to which it has been exposed. Like an avatar for the actual product, the digital twin allows the company to visualize the status and condition of a product that may be thousands of miles away. Digital twins may also provide new insights into how products can be better designed, manufactured, operated, and serviced.

Transforming the Value Chain

The powerful new data available to companies, together with new configurations and capabilities of smart, connected products, is restructuring the traditional functions of business—sometimes radically. This transformation started with product development but is playing out across the value chain. As it spreads, functional boundaries are shifting, and new functions are being created.

Product development

Smart, connected products require a fundamental rethinking of design. At the most basic level, product development shifts from largely mechanical engineering to true interdisciplinary systems engineering. Products have become complex systems that contain software and may have as much or more software in the cloud. That’s why design teams are shifting from a majority of mechanical engineers to a majority of software engineers, and some manufacturers, like GE, Airbus, and Danaher, are establishing offices in software-engineering hubs like Boston and Silicon Valley.

Smart, connected products also call for product design principles that depart dramatically from tradition:

Low-cost variability. In conventional products, variability is costly because it requires variation in physical parts. But the software in smart, connected products makes variability far cheaper. For example, John Deere used to manufacture multiple versions of engines, each providing a different level of horsepower. It now can alter the horsepower of a standard physical engine using software alone. Similarly, digital user interfaces can replace dials and buttons, making it easy and less expensive to modify a product by, say, changing control options. Meeting customer needs for variability through software, not hardware, is a critical new design discipline.

Manufacturing goes beyond production of the physical object, because operating a smart, connected product requires a supporting cloud-based system.

Variability is needed not only across customer segments but also across geographies. Software also makes it easier to localize products for different countries and languages. However, emerging local regulations for data standards, such as those governing the transmission of data across national boundaries, require duplication of data storage infrastructure or applications. Such regulations are introducing new country and regional differences, sometimes for political reasons.

Evergreen design. In the old model, products were designed in discrete generations. The new product incorporated a full set of desired improvements, and the design was then fixed until the next generation. Smart, connected products, however, can be continually upgraded via software, often remotely. Products also can be fine-tuned to meet new customer requirements or solve performance issues. The performance of ABB Robotics’ industrial machines, for example, can be remotely monitored and adjusted by end users during operation. Companies can release new features that are works-in-process, not finalized. Recently, Tesla began putting an “autopilot” system in its cars, but with the intention of enhancing the system’s capabilities over time through remote software updates.

New user interfaces and augmented reality. The digital user interface of a smart, connected product can be put into a tablet or smartphone application, enabling remote operation and even eliminating the need for controls in the product itself. As noted, these interfaces are less costly to implement and easier to modify than physical controls, and they enable greater operator mobility.

Some products have begun incorporating a powerful new interface technology called “augmented reality.” Through a smartphone or tablet pointed at the product, or through smart glasses, augmented reality applications tap into the product cloud and generate a digital overlay of the product. This overlay contains monitoring, operating, and service information that makes supporting or servicing the product more efficient. Constructing these powerful digital interfaces is another critical new design discipline.

Ongoing quality management. Testing that tries to replicate the conditions in which customers will use products has long been part of product development. The aim is to ensure that new offerings will live up to their specifications and to minimize warranty claims. Smart, connected products take quality management several steps farther, enabling continuous monitoring of real-world performance data, allowing companies to identify and address design problems that testing failed to expose. In 2013, for example, batteries in two Tesla Model S cars were punctured and caught fire after drivers struck metal objects in the road. The road conditions and speeds leading to the punctures had not been simulated in testing, but Tesla was able to reconstruct them. The company then sent a software update to all vehicles that would raise their suspension under those conditions, significantly reducing the chances of further punctures.

Connected service. Product designs now need to incorporate additional instrumentation, data collection capability, and diagnostic software features that monitor product health and performance and warn service personnel of failures. And as software increases functionality, products can be designed to allow more remote service.

Support for new business models. Smart, connected products let companies switch from transactional selling to product-as-a-service models. However, this shift has product design implications. When a product is delivered as a service, the responsibility for and associated cost of maintenance remain with the manufacturer, and that can alter several design parameters. This is especially true when multiple customers share the product—as is the case at Smoove, a bike-sharing service in France. Smoove has designed its smart, connected bikes with chainless driveshafts, puncture-resistant tires, and antivandal nuts to improve durability and prevent theft.

Products delivered as services must also capture usage data so that customers are appropriately charged. This requires clear thinking about the type and location of sensors, what data will be gathered, and how often it should be analyzed. When Xerox evolved from selling copiers to charging by the document, it added sensors on the photoreceptor drum, feeder output tray, and toner cartridge to enable accurate billing and facilitate the sale of consumables like paper and toner.

System interoperability. As products become components of broader systems, the opportunities for design optimization multiply. Through codesign, companies can simultaneously develop and enhance hardware and software across a family of products, including those of other companies. Take Nest Labs’ self-learning thermostat. It was designed with an application programming interface that allows it to exchange information with other products, such as Kevo’s smart lock. When the home owner enters the house, the Kevo lock communicates that to the Nest thermostat, which then adjusts the temperature to the home owner’s preference.

Manufacturing

Smart, connected products create new production requirements and opportunities. They may even shift final assembly to the customer site, where the last step is loading and configuring software. But more radical still, manufacturing now goes beyond the production of the physical object, because a functioning smart, connected product requires a cloud-based system for operating it throughout its life.

Smart factories. The new capabilities of smart, connected machines are reshaping the operations of manufacturing plants themselves, where machines increasingly can be linked together in systems. In new initiatives like Industrie 4.0 (in Germany) and Smart Manufacturing (in the United States), networked machines fully automate and optimize production. For example, a production machine can detect a potentially dangerous malfunction, shut down other equipment that could be damaged, and direct maintenance staff to the problem.

GE’s Brilliant Factories initiative uses sensors (retrofitted on existing equipment or designed into new equipment) to stream information into a data lake, where it can be analyzed for insights on cutting downtime and improving efficiency. In one plant, this approach doubled the production of defect-free units.

Simplified components. The physical complexity of products often diminishes as functionality moves from mechanical parts to software. This shift eliminates physical components, along with the production steps needed to build and assemble them. Withings, for example, has reduced its blood pressure monitor to a cuff and sensor, eliminating the display through an app that can track blood pressure and send updates directly to clinicians. Similarly, manufacturers of aircraft, automobiles, and boats are moving toward “glass cockpits,” in which a single screen displays numerous configurable gauges. As the physical complexity of products decreases, however, the quantity of sensors and software rises, introducing new parts and complexity.

Reconfigured assembly processes. Manufacturing has evolved toward standardized platforms, with customization of individual products occurring later and later in the assembly process. This approach reaps economies of scale and lowers inventory. Smart, connected products go even further. Software in the product or in the cloud can be loaded or configured well after the product leaves the factory, by a field service technician or even by the customer. New apps can be added or touchscreen keyboards set up for different languages. Product design changes can be incorporated at the last minute, even after delivery.

Continuous product operations. Until now, manufacturing has been a discrete process that ended once the product was shipped. Smart, connected products, however, cannot operate without a cloud-based technology stack. In effect, the stack is a component of the product—one the manufacturer must operate and improve throughout the product’s life. In this sense, manufacturing becomes a permanent process.

Logistics

The earliest roots of smart, connected products were in logistics, which involve the movement of production inputs and outputs and the delivery of products. Commercialized in the 1990s, radio frequency identification, or RFID, tags greatly enhanced the ability to track shipments. Indeed, the term “Internet of Things” was coined by a founder of MIT’s Auto-ID Center, which specialized in RFID research. Today’s smart, connected products take tracking to an entirely new level. Now it can be done continuously, wherever products are, without the need for a scanner, and provides rich information on not just their current location but also their location history, their condition (their temperature, say, or exposure to stresses), and their surrounding environment.

We believe that smart, connected products will ultimately move logistics to a whole new generation. For example, the management of large, far-flung fleets of vehicles is being transformed by the ability to remotely monitor each vehicle’s position and function, check its local traffic and weather conditions, and provide drivers with an optimized delivery schedule. And automated drones capable of dropping packages directly on the customer’s doorstep—which are now being tested by Amazon, Google, and DHL—could revolutionize the delivery process for many products.

Marketing and sales

The ability to remain connected to the product and track how it’s being used shifts the focus of a company’s customer relationship from selling—often a predominantly one-time transaction—to maximizing the customer’s value from the product over time. This opens up important new requirements and opportunities for marketing and sales.

New ways to segment and customize. The data from smart, connected products provides a much sharper picture of product use, showing, for example, which features customers prefer or fail to use. By comparing usage patterns, companies can do much finer customer segmentation—by industry, geography, organizational unit, and even more-granular attributes. Marketers can apply this deeper knowledge to tailor special offers or after-sale service packages, create features for certain segments, and develop more-sophisticated pricing strategies that better match price and value at the segment or even the individual customer level.

New customer relationships. As the focus shifts to providing continual value to the customer, the product becomes a means of delivering that value, rather than the end itself. And because a manufacturer remains connected to customers via the product, it has a new basis for direct and ongoing dialogue with them. Companies are beginning to see the product as a window into the needs and satisfaction of customers, rather than relying on customers to learn about product needs and performance.

All Traffic Solutions, for example, makes smart, connected road signs that measure traffic speed and volume. The signs allow advanced data mining of traffic patterns and help law enforcement and other customers remotely monitor and manage traffic flows. The company’s relationship with customers has shifted from selling signs to selling long-term services that improve safety without the need for police intervention. The signs are simply devices through which traffic management services are customized and delivered.

New business models. Having full transparency about how customers use products helps companies develop entirely new business models. Take Rolls-Royce’s pioneering “power-by-the-hour” model, in which airlines pay for the time jet engines are used in flight, rather than a fixed price plus charges for maintenance and repairs. Today many industrial companies are beginning to offer their products as services—a move that has major implications for sales and marketing. The goal of salespeople becomes customer success over time, instead of just making the sale. That involves creating “win-win” scenarios for the customer and the company.

A focus on systems, not discrete products. As products become components of larger systems, the customer value proposition broadens. Product quality and features need to be supplemented by interoperability with related products. Companies must decide where to play in this new world: Will they compete at the product level; by offering a family of closely linked products; by creating a platform that cuts across all related products; or by doing all three? Sales and marketing teams will need broader knowledge to position their offerings as components of larger smart, connected systems. Partnerships will often be necessary to fill product gaps or connect products to leading platforms. Salespeople will need to be trained to sell with those partners, and incentives will need to accommodate more-complex revenue-sharing models.

Consider SmartThings, which sells in the increasingly crowded do-it-yourself home-automation space. The company has positioned itself with both consumers and manufacturers as an easy-to-use platform for smart home devices. Its platform has a simple user interface and provides an array of standard sensors that measure such things as moisture, smoke, temperature, and motion. The sensors, which can be attached to any home object, automate lighting, home security, and energy conservation. The company also makes it easy to connect smart home devices from a variety of other manufacturers to its hub and has built an extensive partner ecosystem that already encompasses more than 100 compatible products.

After-sale service

For manufacturers of long-lived products, such as industrial equipment, after-sale service can represent significant revenues and profits—partly because traditional service delivery is inherently inefficient. Technicians often must inspect a product to identify the reason for a failure and the parts needed to correct it and then make a second trip to perform the repair.

Smart, connected products improve service and efficiency and enable a fundamental shift from reactive service to preventive, proactive, and remote service:

One-stop service. Because technicians can diagnose problems remotely, they can have the parts needed for repairs in their trucks the first time they arrive at the customer site. They can also have supporting information for executing the repairs. Only one visit is necessary, and success rates rise.

Remote service. Smart, connected products make delivering service via connectivity increasingly feasible. In many cases products can be repaired by remote technicians in the same way that computers are now often fixed. The blood- and urine-analysis equipment made by Sysmex is a good example. Sysmex originally added connectivity to its instruments to allow remote monitoring but now uses it to provide service as well. Service technicians can access just as much information about a machine when they are off-site as when they are on-site. Often they can fix it by rebooting it, delivering a software upgrade, or talking an on-site medical technician through the process. As a result, service costs, equipment downtime, and customer satisfaction have improved dramatically.

Preventive service. Using predictive analytics, organizations can anticipate problems in smart, connected products and take action. Diebold, for example, monitors its automated teller machines for early signs of trouble. It performs the necessary maintenance remotely, if possible, or dispatches a technician to adjust or replace parts. The company can also update a machine with preventive fixes when feature enhancements are added, sometimes remotely.

Augmented-reality-supported service. The vast amounts of data that smart, connected products gather are creating new ways for service personnel to work individually, together, and with customers. One emerging approach utilizes the augmented reality overlays we described earlier. When these include information about a product’s service needs and step-by-step repair instructions, service efficiency and effectiveness can increase dramatically.

New services. The data, connectivity, and analytics available through smart, connected products are expanding the traditional role of the service function and creating new offerings. Indeed, the service organization has become a major source of business innovation in manufacturing, driving increased revenue and profit through new value-added services such as extended warranties and comparative benchmarking across a customer’s equipment, fleet, or industry. The array of solutions that Caterpillar has developed to help customers manage its construction and mining equipment is a good example. After gathering and analyzing data for each machine deployed at a work site, Caterpillar’s service teams advise customers on where to locate equipment, when fewer machines could suffice, when to add new equipment to reduce bottlenecks, and how to achieve higher fuel efficiency throughout a fleet.

Security

Until recently, IT departments in manufacturing companies have been largely responsible for safeguarding firms’ data centers, business systems, computers, and networks. With the advent of smart, connected devices, the game changes dramatically. The job of ensuring IT security now cuts across all functions.

Every smart, connected device may be a point of network access, a target of hackers, or a launchpad for cyberattacks. Smart, connected products are widely distributed, exposed, and hard to protect with physical measures. Because the products themselves often have limited processing power, they cannot support modern security hardware and software.

Smart, connected products share some familiar vulnerabilities with IT in general. For example, they are susceptible to the same type of denial-of-service attack that overwhelms servers and networks with a flood of access requests. However, these products have major new points of vulnerability, and the impact of intrusions can be more severe. Hackers can take control of a product or tap into the sensitive data that moves between it, the manufacturer, and the customer. On the TV program 60 Minutes, DARPA demonstrated how a hacker could gain complete control of a car’s acceleration and braking, for example. The risk posed by hackers penetrating aircraft, automobiles, medical equipment, generators, and other connected products could be far greater than the risks from a breach of a business e-mail server.

Customers expect products and their data to be safe. So a firm’s ability to provide security is becoming a key source of value—and a potential differentiator. Customers with extraordinary security needs, such as the military and defense organizations, may demand special services.

Security will affect multiple functions. Clearly the IT function will continue to play a central role in identifying and implementing best practices for data and network security. And the need to embed security in product design is crucial. Risk models must consider threats across all potential points of access: the device, the network to which it is connected, and the product cloud. New risk-mitigation techniques are emerging: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, for example, has mandated that layered authentication levels and timed usage sessions be built into all medical devices to minimize the risk to patients. Security can also be enhanced by giving customers or users the ability to control when data is transmitted to the cloud and what type of data the manufacturer can collect. Overall, knowledge and best practices for security in a smart, connected world are rapidly evolving.

Data privacy and the fair exchange of value for data are also increasingly important to customers. Creating data policies and communicating them to customers is becoming a central concern of legal, marketing, sales and service, and other departments. In addition to addressing customers’ privacy concerns, data policies must reflect ever-stricter government regulations and transparently define the type of data collected and how it will be used internally and by third parties.

Human resources

A manufacturer of smart, connected products is a cross between a software company and a traditional product company. This mix demands new skills across the value chain, as well as new working styles and cultural norms.

New expertise. The skills needed to design, sell, and service smart, connected products are in high demand but short supply. Indeed, manufacturers are experiencing a growing sense of urgency about finding the right talent as their skill requirements shift from mechanical engineering to software engineering, from selling products to selling services, and from repairing products to managing product uptime.

Manufacturers will have to hire experts in applications engineering, user interface development, and systems integration, and, most notably, data scientists capable of building and running the automated analytics that help translate data into action. The business or data analyst of the past is evolving into a new type of professional, who must possess both technical and business acumen as well as the ability to communicate insights from analytics to business and IT leaders.

The shortage of these new skills is especially acute in traditional manufacturing centers, many of which are different from technology hubs. So some manufacturers are establishing a physical presence in hot spots such as Boston and Silicon Valley, which combine a presence in advanced manufacturing with academic centers, makers of B2B hardware and software, and emerging producers of smart, connected products. Schneider Electric, for example, is moving its U.S. headquarters to Boston. Over the next decade, manufacturers can accelerate their learning and improve recruiting by being in such clusters. But they will also need new recruiting models, like internship programs with local universities and liaison programs to “borrow” talent from leading technology vendors.

New cultures. Manufacturing smart, connected products requires far more coordination across functions and disciplines than traditional manufacturing does. It also involves integrating staff with varied work styles and from more-diverse backgrounds and cultures—which can be challenging. For instance, the “clock speed” of software development is generally much faster than that of traditional manufacturing. HR organizations will have to rethink many aspects of organizational structure, policies, and norms.

New compensation models. Manufacturers will also need new approaches to attracting and motivating talent. Perks like job flexibility, concierge services, sabbaticals, and free time to work on side projects of personal interest are the norm in high-tech firms employing the type of talent manufacturing companies will increasingly require.

Implications for Organizational Structure

The shifting nature of work throughout the value chain is ushering in a historic organizational transformation of the manufacturing firm. Jeff Immelt, the CEO of General Electric, once said that every industrial company must become a software company. This statement reflects the fact that software is becoming an essential part of products. Beyond this, software firms have already moved in directions essential to competing in smart, connected products, such as evergreen design, remote upgrading, and product-as-a-service models. (See the sidebar “Lessons from the Software Industry.”)

Yet the transformation of the manufacturing firm will be even bigger than what software companies have undergone. While incorporating software, the cloud, and data analytics, manufacturing firms must continue to design, produce, and support complex physical products.

Which aspects of the organizational structure will be affected? As Jay W. Lorsch and Paul R. Lawrence argued in the classic work Organization and Environment, every organizational structure must combine two basic elements: differentiation and integration. Dissimilar tasks, such as sales and engineering, need to be “differentiated,” or organized into distinct units. At the same time, the activities of those separate units need to be “integrated” to coordinate and align them. Smart, connected products have a major impact on both differentiation and integration in manufacturing.

In the classic structure, a manufacturing business is divided into functional units, such as R&D, manufacturing, logistics, sales, marketing, after-sale service, finance, and IT. (While there is also a geographic dimension of organizational structure, which adds a layer of complexity, it is less affected by smart, connected products per se.) These functional units enjoy substantial autonomy. Though integration across them is essential, much of it tends to be relatively episodic and tactical. In addition to achieving alignment on the overall strategy and business plan, functions need to coordinate to manage key handoffs in the product life cycle (design to manufacturing, sales to service, and so on) and capture feedback from the field that will improve processes and products (information on defects, customer reactions). Integration across functional units happens largely through the business unit leadership team and through the design of formal processes for product development, supply chain management, order processing, and the like, in which multiple units have roles.

With the emergence of smart, connected products, however, this classic model breaks down. The need to coordinate across product design, cloud operation, service improvement, and customer engagement is continuous and never ends, even after the sale. Periodic handoffs no longer suffice. Intense, ongoing coordination becomes necessary across multiple functions, including design, operations, sales, service, and IT. Functional roles overlap and blur. In addition, completely new and critical functions emerge—for instance, to manage all the new data and the new open-ended customer relationships. At the broadest level, the rich data and real-time feedback from smart, connected products challenge the traditional centralized command-and-control model of management in favor of distributed but highly integrated choices and continuous improvement.

On top of this, manufacturers must keep producing and supporting conventional products, and that’s not likely to change—in some cases, for decades. Even in today’s progressive, established manufacturing companies, smart, connected products represent less than half of all products sold. The continued coexistence of the new and the old will complicate organizational structures.

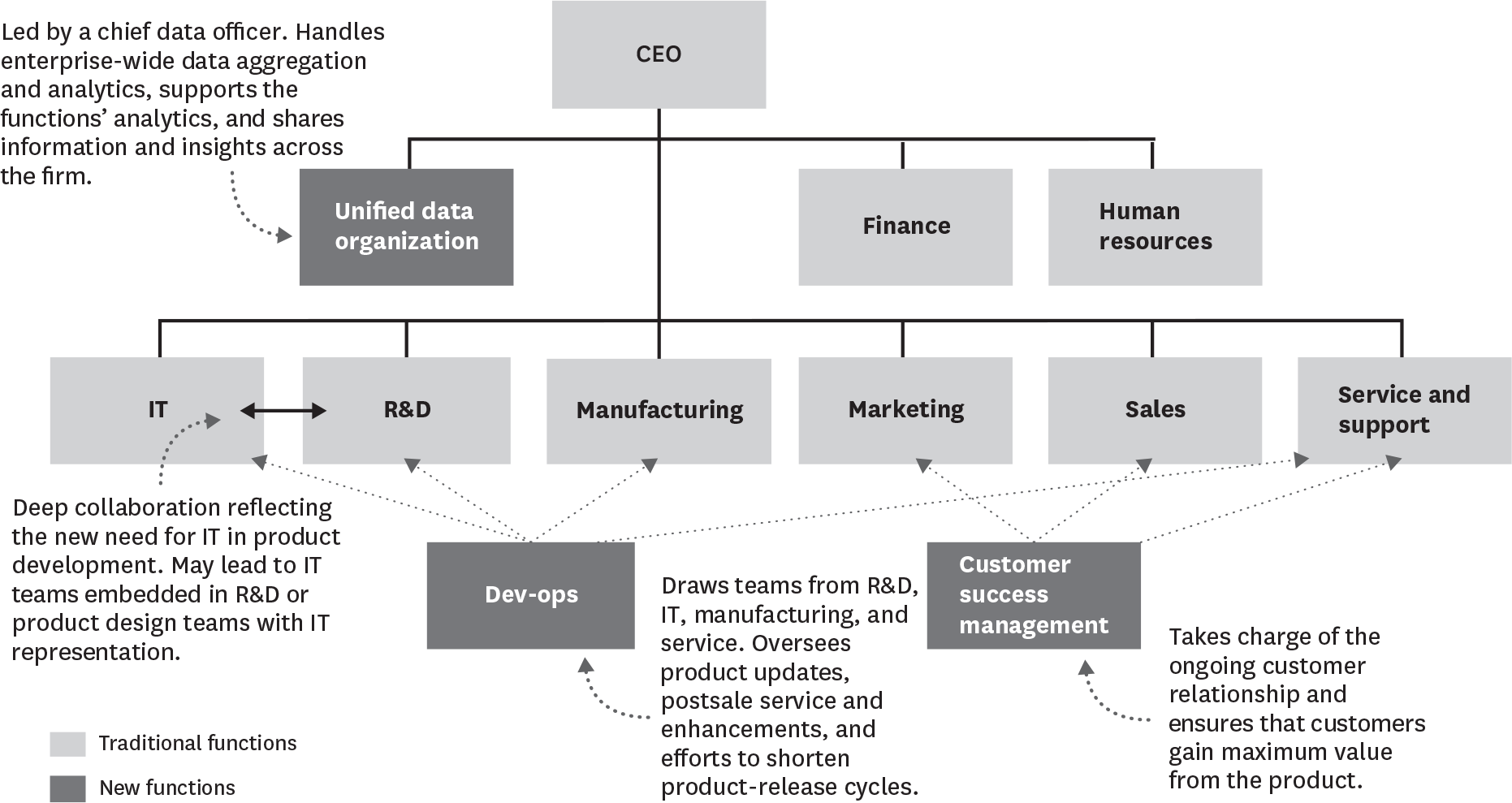

What will the new manufacturing organization look like? Organizational structures are in rapid flux, even among the leading makers of smart, connected products. However, a number of important shifts are becoming evident. The first is more and deeper collaboration and integration between IT and R&D. Over time those units—and others—may start to merge. In addition, companies are beginning to form three new kinds of units: unified data organizations, development-operations groups (or dev-ops), and customer success management units. (See the exhibit “A new organizational structure.”) Meanwhile, product and data security activities are rapidly expanding and now cut across multiple units, though it remains unclear what structure will eventually emerge. Ultimately, virtually every traditional function will also need to be restructured, given the dramatic realignment of tasks and roles taking place.

A new organizational structure

Smart, connected products require functions within manufacturing firms to collaborate in new ways. As a result, firms’ structures are rapidly evolving. A new functional unit focused on data management is starting to appear. Though rare, units focused on ongoing product development and customer success are also beginning to be recognized.

Collaboration between IT and R&D

Traditionally, R&D created products, while IT was primarily concerned with companywide computing infrastructure and managing the software tools the functional groups used, such as computer-aided design, enterprise resource planning, and customer relationship management. With the development of smart, connected products, however, IT must assume a more central role. IT hardware and software are now embedded in products and in the entire technology stack. The question is, who should be responsible for this new technology infrastructure: IT, R&D, or some combination of both?

Only IT currently has the skills to support the software-based technologies and related infrastructure that smart, connected products require. R&D organizations, for their part, have been good at developing and combining mechanical and electrical components, and many have begun to master the challenge of incorporating software in products. Few R&D organizations, however, have deep experience in building and managing the cloud-based elements of the technology stack. Now, IT and R&D must integrate their activities on a continual basis. Yet the two functions have little history of collaboration on product development—and in some organizations have a history of animosity.

Various organizational models for this new relationship are emerging. Some companies are embedding IT teams within R&D departments. Others are establishing cross-functional product design teams that include IT representation while maintaining separate reporting lines. For example, at Ventana Medical Systems, a maker of smart, connected lab equipment, the IT and R&D teams now work jointly on product development, with IT weighing in heavily on choices about what product functionality should be delivered in the cloud and when software updates are needed. At Thermo Fisher Scientific, a scientific instrument leader, members of the IT department work directly inside R&D, with a dotted-line reporting structure and shared goals. This has improved Thermo Fisher’s effectiveness at defining and building the product cloud; securely capturing, analyzing, and storing product data; and distributing data both internally and to customers.

A unified data organization

Because of the growing volume, complexity, and strategic importance of data, it is no longer desirable or even feasible for each function to manage data by itself, build its own data analytics capability, or handle its own data security. To get the most out of the new data resources, many companies are creating dedicated data groups that consolidate data collection, aggregation, and analytics, and are responsible for making data and insights available across functions and business units. The research firm Gartner predicts that by 2017 as many as a quarter of all large firms will have dedicated data units.

The new data organizations usually are led by a C-level executive, the chief data officer, who reports to the CEO or sometimes to the CFO or CIO. He or she is responsible for unified data management, educating the organization on how to apply data resources, overseeing data rights and access, and driving the application of advanced data analytics across the value chain. Ford Motor Company, for example, recently appointed a chief data and analytics officer to develop and execute an enterprise-wide vision for data analysis. The CDO is spearheading the company’s use of smart, connected product data to understand customer preferences, shape future strategies for connected cars, and restructure internal processes.

Dev-ops

The imperatives of evergreen product design, continuous product operation and support, and ongoing product upgrades are creating a need for a new functional group, sometimes called dev-ops. (The term comes from the software industry, where it is used to describe a collaborative, cross-functional software development and deployment method.) The dev-ops unit is responsible for managing and optimizing the ongoing performance of connected products after they have left the factory. It brings together software-engineering experts from the traditional product-development organization (the “dev”) with staff members from IT, manufacturing, and service who are responsible for product operation (the “ops”).

Dev-ops organizes and leads teams that shorten product-release cycles, manage product updates and patches, and deliver new services and enhancements postsale. It oversees the frequent release of small, carefully tested batches of product changes into the shared cloud, ideally with no disruption to existing products and users in the field. The dev-ops organization also leads the work to enhance preventive service models and product maintenance.

Customer success management

A third new organizational unit, which also has an analogue in the software industry, is responsible for managing the customer experience and ensuring that customers get the most from the product. This task is crucial with smart, connected products, especially to ensure renewals in product-as-a-service models. The customer success management unit does not necessarily replace sales or service units but assumes primary responsibility for customer relationships after the sale. This unit performs roles that traditional sales and service organizations are not equipped for and don’t have incentives to adopt: monitoring product use and performance data to gauge the value customers capture and identifying ways to increase it. This new unit does not operate as a self-contained silo but collaborates on an ongoing basis with marketing, sales, and service.

Customer success units are changing the management of customer relationships. Historically, customer surveys and call centers have been the principal ways companies gather insights about product use and determine when a customer relationship is in jeopardy. Companies typically hear most from customers when something goes wrong—and often not until it is too late.

With smart, connected products, the product itself becomes a sensor that gauges the value customers are receiving. Through the data it generates, a product can tell companies a lot about the customer experience: about product use and performance, customer preferences, and customer satisfaction. Such insights can prevent customer defections and reveal where a customer could benefit from additional product capabilities or services.

Shared responsibility for security

In most companies, executive oversight of security is in flux. Security may report to the chief information officer, the chief technology officer, the chief data officer, or the chief compliance officer. Whatever the leadership structure, security cuts across product development, dev-ops, IT, the field service group, and other units. Especially strong collaboration among R&D, IT, and the data organization is essential. The data organization, along with IT, will normally be responsible for securing product data, defining user access and rights protocols, and identifying and complying with regulations. The R&D and dev-ops teams will take the lead on reducing vulnerabilities in the physical product. IT and R&D will often be jointly responsible for maintaining and protecting the product cloud and its connections to the product. However, the organizational model for managing security is still being written.

Making the Transition

How do we get from here to there? The organizational changes we have described are substantial. Today centralized data groups are just beginning to appear, and the integration of IT and R&D is in a very early stage. Dev-ops and customer success management units are rare, but their roles are starting to be recognized and differentiated. Over time these may emerge as formal functional units.

At manufacturers in fields like aircraft, medical devices, and agricultural equipment, smart, connected products will need to coexist with traditional products for a sustained period. This means that the organizational transformation we are describing will be evolutionary, not revolutionary, and old and new structures will often need to operate in parallel.

Given the scope of the changes, and the scarcity of skills and experience in smart, connected products, many companies will need to pursue hybrid or transitional structures. This will allow scarce talent to be leveraged, experience pooled, and duplication avoided.

What could this transitional structure look like? At the business unit level many companies have encouraged organic smart, connected product initiatives. A function like IT might be assigned the lead role for smart, connected product strategy and deployment. Or a special steering committee made up of the functional heads may be asked to champion and oversee this effort. Some firms are acquiring or partnering with focused software companies for smart, connected product initiatives, injecting new talent and perspectives into their organizations. Caterpillar recently made such a move by investing in Uptake, a predictive analytics firm.

At the corporate level in multibusiness companies, overlay structures are being put in place to evangelize the smart, connected products opportunity, identify the best places to start, avoid duplication, build a critical mass of talent and expertise, and oversee technology infrastructure. These units often have CEO or senior management sponsorship. We are seeing three models emerging:

Stand-alone business unit

A separate new unit, with profit-and-loss responsibility, is put in charge of supporting the company’s smart, connected products strategy. The unit aggregates the talent and mobilizes the technology and assets needed to bring such new offerings to market, working with all affected business units. The Bosch Group is one company that has formed such a dedicated unit, Bosch Software Innovations. It enables the company’s product-based business units and external customers to build services for smart, connected products.

A new stand-alone unit is free from the constraints of legacy business processes and organizational structures. In some companies, as expertise, infrastructure, and experience grow, leadership may start shifting back to the business units over time. In other cases, stand-alone units may deter, rather than enable, initiatives in the individual business units. Also, knowledge acquired by a stand-alone unit may disseminate more slowly across the firm.

Center of excellence

In this model, a separate corporate unit houses key expertise on smart, connected products. It does not have profit-and-loss responsibility but is a cost center that business units can tap. GE has such a center of excellence in Silicon Valley.

Cross-business-unit steering committee

This approach involves convening a committee of thought leaders across the various business units, who champion opportunities, share expertise, and facilitate collaboration. Such committees usually lack formal decision-making authority, which can limit their ability to drive change.

The Broader Implications

Smart, connected products are dramatically changing opportunities for value creation in the economy. A revolution is under way in manufacturing. The effects are not confined to manufacturing, however, but are spreading to other industries that use—or could use—smart, connected products, including services. (See the sidebar “How Smart, Connected Products Change Services.”) And the impact of smart, connected products is still in the early innings.

Smart, connected products reshape not only competition, as we detailed in our previous article, but the very nature of the manufacturing firm, its work, and how it is organized. They are creating the first true discontinuity in the organization of manufacturing firms in modern business history. Many of the same organizational changes and challenges will spread to other fields as well.

For companies grappling with the transition, organizational issues are now center stage—and there is no playbook. We are just beginning the process of rewriting the organization chart that has been in place for decades.

While the transition may be unsettling and destabilizing for many companies and raise real competitive challenges and security concerns, it is important to see smart, connected products first and foremost as a chance to improve economies and society. Because of these new products, we are poised to make great progress in environmental stewardship—substantially increasing the efficiency of land, water, and materials use, as well as energy efficiency and the productivity of the food system. They can help us achieve major advances in the human condition—in health, safety, mobility, training, and more—and help us with daily challenges, like easily finding a parking place.

And they position us to change the trajectory of society’s overall consumption. After decades of ever more, ever cheaper, and ever more disposable everything, businesses and consumers may well need fewer things. Smart, connected products will free us to purchase only the goods and services we need, to share products that we do not use much, and to get more out of the products that we already have. Instead of tossing out old products for the next generation, we will hold on to products that are continually improved, upgraded, and modernized.

But what about work? Any major technological discontinuity raises inevitable concerns about its effect on jobs and opportunity, particularly in this day and age. We believe that the exponential opportunities for innovation presented by smart, connected products, together with the huge expansion of data they create about almost everything, will be a net generator of economic growth. These new types of products will not reduce our needs or the number of people required to meet them. Instead, new industries, new services, and new roles will be created that can allow more people to meet their aspirations.

What about those without the education and skills needed for the first wave of jobs in the transition? Those skills are in short supply, but the broader impact on employment and growth is likely to be positive. There will be more innovation and many new businesses. And smart, connected products can be a leveler, allowing people to work more productively and in less rote and repetitive ways. Equip a service technician with an augmented reality application and a smartphone, and he or she can do a complex repair even with limited training. Less skilled workers can be coached and guided far more easily by experts. Imagine how a landscaper’s job could change when yards and gardens are instrumented with sensors that provide information about the soil, watering history, plant health, and problem areas.

Manufacturers are leading the charge toward this future. The product and organizational transformations required are difficult and uncertain. The companies and other institutions that can speed this journey will prosper and make a profound difference for society.

The authors would like to acknowledge the extensive and invaluable assistance of Kathleen Mitford, Eric Snow, Alexandra Houghtalin, and Danny Bressler in the preparation of this article.

Disclosure: PTC does business with more than 28,000 companies worldwide, many of which are mentioned in this article.

Originally published in October 2015. Reprint R1510G