Cartridges and Home Consoles (1976–1984)

The Second Generation of Home Consoles

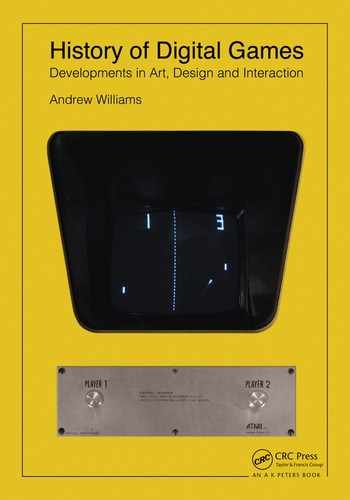

Dedicated units that played variations of ping-pong dominated the first generation of home consoles. A major drawback of these machines, however, revolved around their inability to offer new content; once the novelty of playing the game wore off, players quickly tired of them. As discussed in Chapter 3, these machines flooded consumer outlets in the mid- to late 1970s and contributed to the market crash of 1977. Just prior to this slowdown, however, Fairchild Semiconductor followed by Atari each explored an alternative approach to home consoles (Figure 5.1). This approach took inspiration from computers as a single program could be switched into and out of the console’s memory, potentially allowed for an infinite library of games. Other companies later followed this design concept as well, resulting in fierce competition as the home console market expanded rapidly in the early 1980s. Spanning approximately from 1976 to 1983, these “second-generation” consoles introduced game concepts and business practices that shaped the industry’s development for decades.

FIGURE 5.1 Fairchild Semiconductor released the first true cartridge-based home console in 1976. The main unit, designed by engineer Jerry Lawson, contained a number of built-in games as well as a cartridge port. The most notable feature of the unit was its unconventional controllers that combined a push button and rotary-like directional controller on a stick. (Photo Evan Amos. CC BY-SA 3.0.)

Like prior dedicated consoles, arcade titles helped drive the popularity of the second generation. Atari, the largest coin-op game developer, particularly benefitted from porting its catalog of arcade hits to its home consoles, while Coleco pursued exclusive licenses with arcade game developers. Even games not originating in the arcade were commonly designed with arcade game-like qualities. Despite the dominance of design ideas inherited from the arcades, the period saw the early development of a new approach to games that were more suited for play at home. These games utilized larger, more complex game spaces and centered their play on exploration and the discovery of the unknown. As such, their length of gameplay was measured in increments of tens of minutes, or in the most extreme cases, hours, as opposed to the 90 seconds of gameplay favored by arcade game designers.

New ideas in game design coupled with arcade hits reconfigured for home use, accelerated the young industry’s growth in the early 1980s. By 1982, the industry had reached unprecedented heights only to be followed by a dramatic reversal. Multiple attempts at fast grabs for profit resulted in poorly designed games and created instability that weakened consumer demand and led to a collapse of the North American game industry in 1983. Companies like Atari saw its divisions spun off while many others, like Coleco and Mattel, exited the videogame market entirely. The void left behind allowed Japanese companies like Nintendo, Sega, and eventually Sony, to dominate the home console market from the late 1980s through much of the present day.

Following the success of its home Pong unit, Atari released a cartridge-based console in 1977 called the “Video Computer System” or VCS (later renamed the 2600 after its product number). Since the console was intended for use in the home living room, the unit, like the Odyssey and Channel F, was designed with a faux wood front that matched home electronic trends of the 1970s. It was the unit’s most iconic physical feature (Figure 5.2). Atari’s arcade game background was apparent in the design of the unit’s two main controllers: one a rotary-dial paddle and the other, a single-button joystick. The joystick, however, was not particularly well-suited for operation in the home as a player needed to hold its base in one hand and manipulate the stick with the other. While this awkwardness led to frequent hand cramping, it nonetheless allowed game designers to more easily translate the basic controls of arcade games to home units.

FIGURE 5.2 The first of several models of Atari’s Video Computer System known as the “Heavy Sixer.” Like Atari’s Pong console, Sears released a version of the VCS as well as numerous cartridges under its “Telegames” brand. (Photo by Evan Amos.)

The VCS, like other consoles of the time, was presented to the public as a machine capable of many applications. Its launch titles ranged from Basic Math (1977, Atari), an educational program centered on solving elementary-level math problems, to a simulation of the card game, Blackjack (1977, Atari). The majority of the launch titles, however, consisted of games either directly ported from or inspired by popular arcade games: Surround (1977, Atari) was effectively the dueling maze game Blockade, Indy 500 (1977, Atari) included a port of Atari’s Crash n’ Score as well as a game similar to Gran Trak 10, Combat (1977, Atari) contained versions of Tank (1974) and Jet Fighter (1975), while Video Olympics (1977, Atari) featured a number of Atari’s Pong variants. The debut of the VCS, however, was not met with immediate success: issues in production quality plagued the system and the glut of dedicated consoles slowed sales of home video games. In 1980, fortunes reversed as the VCS saw major gains, becoming the leader in the home market and overshadowing the Fairchild Channel F.

The majority of development time for VCS games was spent primarily on finding ways to display the game and achieve the programmer’s goals as the machine had a strict set of limitations. From its earliest conception, the VCS was designed to play ball and paddle games like Pong and Quadrapong and dueling/shooting games like Tank and Jet Fighter. As such, the unit’s hardware was designed to produce two projectiles, a ball and two player-controlled sprites—independently moving objects placed on top of a background. Additionally the cartridges loaded into the unit initially held only 2–4 kilobytes of memory, while the VCS could only hold a maximum of 128 bytes of data.

Despite these limitations, the VCS was remarkably flexible once its unique properties were mastered resulting in greater longevity than expected. Video Chess (1979, Atari), for example, presented a particularly clever set of solutions to these limitations. Although it took programmer Larry Wagner two years to write an algorithm to play chess on the VCS, one of the most difficult parts was representing the pieces on the screen. A standard game of chess gives each player 16 pieces to control distributed in two rows of eight. Translating this to the VCS meant placing eight sprites in a row. While certain techniques allowed programmers to place more sprites on the screen, eight sprites placed next to each other exceeded the unit’s capabilities. Aiding Wagner was fellow Atari programmer Bob Whitehead who developed a graphical technique called venetian blinds, which broke each chess piece into segments of horizontal lines and horizontal spaces. Every other piece was then offset relative to its neighbors, creating a slight wave-like pattern among the rows of pieces. This technique reduced the number of sprites per row from eight to four, which when combined with other techniques, allowed the VCS to display a full game of chess. The venetian blinds technique was employed in several other games and is noticeable in the score readout for the VCS version of Space Invaders (1980, Atari) (Figure 5.3). Video Chess, however, was so taxing on the machine that it did not have enough resources to calculate the computer opponent’s move and display the pieces at the same time. This resulted in a random sequence of colors briefly flashing across the screen between turns.

FIGURE 5.3 Space Invaders (1980, Atari) for the Atari VCS.

The development of Video Chess also led programmers to employ bank switching on the VCS. Although the final version of Video Chess did not utilize it, bank switching was a solution that allowed programmers to utilize a double-sized, 8-kilobyte cartridge. With more space, games could feature more game content, higher quality animations, and greater variety of visuals. The 1981 VCS port of Asteroids first made use of the technique. As the price of the higher capacity cartridges had become more cost-effective, both Atari and its competitors utilized this technique.

A number of changes occurred at Atari in the mid- to late 1970s. Atari needed a significant injection of capital to produce the VCS, resulting in the company’s sale to Warner Communications in 1976. With Warner’s backing, Atari’s facilities expanded and its already impressive international presence grew even larger. The purchase, however, eventually led to friction as Warner Communications’ traditional management structure clashed with the loose business culture at Atari. This, along with Nolan Bushnell becoming increasingly distracted by his new side venture, Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatre, forced Warner Communications to initiate change. Bushnell was removed from executive functions and left Atari in 1979. After Bushnell, several others of the company’s original management departed as well. In the wake of these high-profile departures, the new managers at Atari realigned company focus to favor marketing and advertising and put greater attention on the VCS. Marketing thus began to dictate not only which games would be made, but also when they were to be released. This led to an aggressive period of licensing arcade hits outside of Atari’s catalog. The first was an adaption of Nishikado’s Space Invaders arcade game to the VCS (Figure 5.3). The popularity of the arcade version of Space Invaders translated to the home as players bought new VCSs just to play the game at home. While this led to phenomenal short-term profits, it created a number of weaknesses that eventually came back to haunt the company.

Competition in the Home Market

The Emergence of Third-Party Developers

Throughout the second generation, it was common for a single individual to be responsible for all parts of a game’s development—the design, programming, graphics, sound, etc. As such, the work of particularly talented individuals translated into great profits for the company. The games created by David Crane, Bob Whitehead, Alan Miller, and Larry Kaplan, for example, consisted of more than half of Atari’s profits in 1978. While the company had a good year and the executives received lavish bonuses, its programmers saw no change in compensation and no public credit for their work. When Crane raised these concerns to the company’s upper management, they were turned away. Further, in a news article about the company, Atari’s new president referred to its VCS programmers as “high strung prima donnas,” an off interview quote that was published as part of the story. Disgruntled, Crane, Whitehead, Miller, and Kaplan departed Atari in 1979 and with former Intellivision programmers, founded their own game company, Activision. In 1981, Atari programmers Rob Fulop, Dennis Kolbe, Bob Smith, and others also departed under the same circumstances, founding Imagic. The resentment of these ex-Atari employees was made clear as the instruction booklets for both Activision and Imagic games identified the programmers by name. Activision went a step further and occasionally included the programmer’s name on the cartridge label, along with a picture and a personal message that unambiguously established authorship.

These “third party” software developers such as Activision, Imagic, and soon many more, represented a new practice in the game industry as studios created games for hardware they did not own. As a result, both Activision and Imagic became direct competitors to Atari, producing a number of highly innovative and original games for not only the Atari VCS, but also other gaming platforms such as the Intellivision, ColecoVision, and numerous early home computers. The greater variety of game ideas resulted in successful sales and helped keep the VCS in high demand through the early 1980s as competition drove each of the companies to excel. Although Atari brought suits against Activision, the case was thrown out. This effectively provided the legal basis for one company to produce software for another company’s product, resulting in a flood of other startups that also wanted to produce games for the VCS. Although Atari’s management eventually granted its VCS programmers profit sharing through bonus packages, it had already lost some of its most talented designers and created some of its strongest competitors.

The games produced for the VCS by Activision and Imagic were visually distinctive from those of Atari. Both companies used brighter, more saturated colors for their game worlds and featured some of the most advanced animations for the platform. David Crane’s Grand Prix (1982, Activision) went beyond any of the previous race games offered on VCS as it included multi-colored vehicles complete with tires that simulated rotation at different speeds. Imagic meanwhile, established the first art department and hired artist Michael Becker as the industry’s first videogame art director. This move was prompted by the state of visual quality in many second-generation games as programmers often did not have a background in art. With a dedicated art department, not only did visuals improve, but the process of creating them changed as well. Typically, a programmer laid out images on graph paper, which allowed one to code the coordinates of the individual pixels and their colors into the game. As this labor-intensive method was slow and discouraged refining game visuals, Bob Smith and Rob Fulop created tools that allowed artists to quickly edit pixel art and translate it into computer code. Imagic’s Michael Becker first used these tools to create the demon characters for Rob Fulop’s Demon Attack (1982), which received accolades for its art, animation, and gameplay. Soon after, as games grew in complexity, it became increasingly common to divide the work of making a game between programmers and artists.

GAME AUTHORSHIP AND EASTER EGGS

Throughout the second generation, many programmers hid their names or initials in their games. These Easter eggs typically required a great deal of effort by the player to find—effectively a separate game played between programmer and player. The first known occurrence of hidden names appeared on games for the Fairchild Channel F. A collection of demonstration programs for the system known as Democart (1977) revealed the name of programmer Michael Glass if a certain combination of the machine’s buttons was pressed at the demo’s end. Video Whizball (1978) displayed the name “Reid-Selth” for its programmer Brad Reid-Selth if the player performed a sequence of actions before starting a new game. The complexity of these unofficial parts of the program grew quickly. Warren Robinett’s Adventure (1979, Atari) contained a secret room that displayed his name but was only accessible if the player found a one-pixel gray box concealed in a gray wall, then used it to walk through an impassable border. Although executives at Atari and other companies were initially unaware that their programmers were hiding their names, Atari, in particular, decided that Easter eggs like these and others a desirable mystique and sanctioned their creation.

Howard Scott Warshaw of Atari created some of the most elaborate and playful Easter eggs of the era that not only revealed his initials, but also referenced his game career: after collecting seven Reese’s Pieces and turning them into Elliot in Warshaw’s third game, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), the player could revive a dying flower that turned into an animated “Yar” from Yar’s Revenge (1982). The second time the player performed this task, the flower changed into an “Indy” from Raiders of the Lost Ark (1982). A third time revealed the initials “HSW3” in the score area, to signify E.T. as Howard Scott Warshaw’s third game.

The creator’s name or identity as an Easter egg continued beyond the second generation almost as a tradition of the medium. Mortal Kombat II (1993, Midway) contained a secret playable fighter named “Noob Saibot,” the reverse spelling of the game’s main creators, Ed Boon and John Tobias while Doom II: Hell on Earth (1994, id Software) used a hidden target in the game’s final boss battle—the severed head of its founder John Romero.

Mattel and Coleco Enter the Console Market

Beginning in 1976, toy company Mattel released a number of L.E.D. handheld games based on various sports themes. The following year, the company began developing the Intellivision, a home videogame console designed to compete against Atari’s VCS. The popularity of the handheld games, however, and Mattel’s reluctance to directly compete against Atari, delayed serious action until the Intellivision was released in 1980. Much like Atari’s VCS, the initial Intellivision game catalog concentrated on variety, featuring sports games, with a few gambling, board, and arcade-style games. Mattel’s marketing strategy presented the Intellivision as a sophisticated, educational, and family-oriented entertainment system; it was “intelligent television.” The campaign also was keen to draw visual comparisons between the Intellivision and VCS using sports games. Since the Intellivision could more easily display a larger number of sprites, it was more able to represent popular sports like football and baseball. The use of well-known journalist George Plimpton as spokesperson further cemented the Intellivision’s identity.

By 1982, however, the boom of the Golden Age arcade directed Mattel to pursue more shooting-oriented games. A number of licensed arcade ports produced by rival Coleco also made an appearance on the system at this time. The Intellivision proved a strong competitor to the VCS and inaugurated the first of many “console wars” in home videogames. In reaction to this, Atari rushed production of the VCS’s successor, the Atari 5200 Super System, a decision that also would hurt the company. Atari had recognized that arcade games helped sell home units and thus designed the 5200 using the sophisticated hardware from its 400/800 line of home computers (see Chapter 6). Although more powerful, the 5200 struggled to gain traction: it lacked unique game offerings and its poorly designed controllers featured a non-centering joystick that made gameplay feel “sloppy” (Figure 5.7). In addition, much of the built-up anticipation for the Atari 5200 was deflated after Coleco released its sophisticated home system in 1982, the ColecoVision.

Coleco emerged from the market crash of 1977 in financial straits. Although its line of Telstar dedicated consoles, powered by the General Instruments AY-3-8500 “Pong-on-a-chip,” had been successful, the flooded market created difficult to absorb financial losses. Coleco’s management, however, was undeterred and, like Mattel, produced a number of handheld sports games in the late 1970s. The surge in popularity of arcade games in the early 1980s led Coleco to wisely secure exclusive licenses with a number of Japanese game companies including Nintendo, Namco, Konami, and Sega. Coleco used these licenses to produce a line of miniature arcade cabinets, complete with replicated cabinet art and joysticks (Figure 5.4). Seeing an opportunity to compete with both Atari and Mattel, Coleco used its exclusive licenses to push its 1982 cartridge-based home console, the ColecoVision. In a stroke of masterful marketing, they packaged the ColecoVision with a port of Donkey Kong, which, of all second-generation consoles, most closely replicated the images and sound of Shigeru Miyamoto’s original arcade game. Coleco’s exclusive rights to the home version of many Golden Age greats also allowed it to produce arcade game ports for both the VCS and Intellivision. This earned the company significant sales across all platforms and provided constant opportunities to show the graphical superiority of its own system.

FIGURE 5.4 Coleco’s Mini Arcade cabinets used VFD technology to create bright colors that other small LED and LCD units could not replicate.

Despite being underpowered compared to its rivals, the VCS had a head start, a well-developed library of ports from Atari’s arcade division, a few exclusive licensing deals and robust third-party development. These circumstances allowed Atari’s VCS console to remain competitive in the early 1980s. Both Mattel and Coleco targeted these great advantages by creating accessories that allowed their systems to play Atari’s VCS games. The 1982 “Expansion Module 1” for the ColecoVision and the 1983 “System Changer” for the Intellivision plugged into each console and accepted Atari cartridges. Even Atari released an add-on that allowed its floundering 5200 console to play VCS games, although some models required an upgrade at an official Atari service center first. The introduction of these add-ons resulted in numerous marketing campaigns where each system, aided by the extensive VCS catalog, claimed the ability to play the most games.

Adding Content to Home Console Games

Arcade games were the single greatest influence on designers of second-generation home console hardware and games, especially so after 1980. Much of this was due to the desire to replicate the proven designs of certain coin-op games. As such, designers of home console games like K.C. Munchkin! (1981, Magnavox) and Astrosmash (1981, Mattel) strove to create the tension and action of arcade games like Pac-Man, Space Invaders, and Asteroids. The economics that shaped game design in the arcade, however, were not the same as those of the home. Without the need to insert a quarter into the machine, home video games lost the single greatest choice made by the player—whether to play the game again. With replay as a given, games for the home would be played more frequently. Quick deaths and rapid increases in difficulty would not justify the significantly greater cost for those who purchased game cartridges. Designers, thus, needed a way to extend the length of a player’s interaction while still employing the qualities that made arcade games enjoyable.

The most common solution to extend play was to allow the player to choose the level of game difficulty. This setting typically governed the number of lives one received, speed of enemies, or other variables that aided or hindered the player’s performance. The 1982 version of Donkey Kong for the Colecovision, for example, offered a number of skill levels that set the game’s countdown timer at higher or lower values, while the difficulty switches for the VCS’s version of Frogger (1982, Parker Brothers) controlled how soon the game’s more difficult enemies appeared.

Another typical approach was a “game select” option that could substantially change the nature of gameplay by altering rules. The Space Invaders-inspired, Alien Invasion (1981, Fairchild Semiconductor) for the Fairchild Channel F, for instance, featured 10 variations that allowed the player to control the number of shots at a time by both player and aliens. Although seemingly minor, these rule changes resulted in different gameplay experiences. Games on the VCS were particularly notable for their high number of variations. The two-player dueling game Combat featured 27 variations spread out between six distinct games with different rules and graphics. One of the more eccentric of these was the “Easy Maze, Billiard Hit, Invisible Tank Pong” variation in which the dueling tanks were only visible at certain times and could only score a hit after a projectile bounced off the maze walls at least once. The Atari VCS’s version of Space Invaders contained an astonishing 112 variations and included everything from invisible aliens to a cooperative mode that divided the turret’s left and right movement between two players. Other variants such as those found in Video Olympics and Basketball (1978, Atari) featured options for dueling against a human or computer-controlled opponent. Often, the variations were so numerous that manuals listed them in chart form for easy reference. Since programmers needed every byte possible to create a complete game, these minor manipulations were economical solutions to providing more gameplay.

Altering Time in Home Console Games

In addition to creating minor gameplay variations, game designers explored ways to extend the home gaming experience by altering the way time was used. This undercut a central pillar of arcade game design as a majority of postwar electromechanical arcade games such as K.O. Champ (Figure 1.11) and many early digital arcade games like Death Race (Figure 3.9), gave the player a fixed amount of time for each coin. Additionally, the related rate of increase in game difficulty was also reconsidered. As discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, these systems were designed to limit a player’s game time, allowing the machine to acquire more money through replay or new customers. The modification of this fundamental element of arcade games lowered stress on the player and encouraged a more strategic or leisurely pace of play. These modifications allowed the development of new game forms for home consoles; games focused on the exploration of space and the strategic management of resources. Additionally narrative became increasingly important. Critical to their development were the mainframe computer games of the 1960s and 1970s created and modified by amateur computer programmers. Although several home console games still bore a resemblance to popular maze and shooter-type arcade games, they nonetheless led to meaningful distinctions between games for arcades and games for home consoles.

Adventure and Exploration in Console Games

Game designers had considerable freedom to develop games along their own lines despite management and marketing divisions pushing programmers to create games according to arcade conventions. Adventure (1979), by Atari programmer Warren Robinett, set a precedent for graphics-based adventure games throughout the second generation and beyond. Robinett wished to re-create Don Woods and William Crowther’s 1978 text adventure, Colossal Cave Adventure (see Chapter 6). After he encountered the limitations of the VCS, however, Robinett revised the concept and delivered an innovative experience focused on the search for a chalice through dragon-inhabited mazes and torch-lit catacombs. He translated familiar text adventure keyboard commands “GO NORTH,” “PICK UP SWORD”, and “USE KEY” to the one button Atari joystick: this allowed players to pick up objects by moving over them, to use objects by touching them with other objects, and to drop objects with the push of a button. Without arcade elements such as score, timer, or limited lives, players were free to explore and play at their own pace.

The most novel aspect of Adventure, however, was the space. In order to create a feeling that the player had embarked on a journey, the game spanned a set of screens and took the player through different environments: mazes, castles, and catacombs. The catacombs in particular were visually innovative as the player’s view consisted of a small circle surrounded by blank space that represented movement by torchlight. Throughout their journey, players needed to revisit certain spaces multiple times to collect items or slay dragons, an unconventional use of space in light of the linear progression through levels of arcade games. To add to the already relatively long game, the player could choose a game variation that placed the objects and dragons in random places throughout the game’s world, allowing for a greater degree of replay. These features helped make Adventure one of the most successful games of not only the VCS, but of the entire second generation.

The medieval fantasy theme proved to be useful for extending gameplay through exploration, as the pre-industrial setting conjured images of vast natural landscapes with hidden dangers and rewards. The 1982 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (later retitled Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Cloudy Mountain Cartridge), designed by Tom Loughry for Mattel’s Intellivision console, used this idea by dividing the game space between two levels: a map-like overworld that represented a landscape of multiple terrains and a subterranean maze of cave passages. The player’s task was to find two pieces of a crown guarded by winged dragons in the titular Cloudy Mountain. In order to reach Cloudy Mountain, players needed to make their way through a number of underground passages filled with monsters and, at times, backtrack through previously explored areas to locate crucial items (Figure 5.5).

FIGURE 5.5 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Cloudy Mountain Cartridge (1982, Mattel).

Loughry felt that players needed to be presented with something new each time they played; that surprise and discovery were the key attributes of an enjoyable game. Randomization, thus, was a core part of Cloudy Mountain’s design, as each play session yielded a different configuration of the overworld landscape and subterranean caves. Using similar mechanics as the computer game Rogue (see Chapter 6), the space of each cave in Cloudy Mountain was only revealed by exploration: this resulted in either the surprise of finding a useful item or the shock of seeing a monster. To keep the act of exploration even more full of tension, Loughry programmed the monsters to signal their presence by emitting sounds from off-screen.

Loughry’s follow-up adventure game for the Intellivision, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Treasure of Tarmin Cartridge (1982), proved to be an even greater departure from the arcades. Inspired by a first-person adventure game that Loughry played on a computer mainframe, Treasure of Tarmin provided a sense of immersion not seen on a home console (Figure 5.6). The player, again tasked with finding treasure, descended through increasingly difficult levels of a labyrinth, gathering weapons and armor of varied quality in preparation for a final confrontation with the maze’s minotaur. Randomization again played an important role in the game experience, as each level was assembled from various premade segments and included hidden doors leading to treasure.

FIGURE 5.6 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Treasure of Tarmin Cartridge (1982, Mattel).

OVERLAYS IN LATER SECOND-GENERATION CONTROLLERS

Beginning with the Intellivision, many consoles featured controllers with a numeric keypad similar to that of a touchtone phone (Figure 5.7). This allowed game designers to program more actions and thus give the player more choices, an approach avoided in the simple to control arcade games of the period. The change of input helped remove one of the barriers to creating games that were better suited for play at home.

A problem with this type of controller design, however, was that any one game might use a different configuration of the buttons, leading to difficulties in controlling the game. To avoid confusion, game developers created overlays that slid into the controllers over the keys. The overlays helped direct the player’s attention as unused keys were blocked out and active keys were given meaning with labels and graphics. The Intellivision, Emerson Arcadia 2001, ColecoVision, and Atari 5200 all used this method. Despite being widespread, controller overlays were short lived. Third- and fourth-generation consoles moved away from remotes with keypads and adopted game pads with a simpler button and d-pad setup.

FIGURE 5.7 Atari 5200 Super System Controllers with overlays for Space Invaders and Soccer. Each reveals the different input needs of each game.

One of Loughry’s main concerns with a first-person perspective was the ease with which a player could get lost. To help prevent this he incorporated a compass in the interface, a screen-wipe that originated from the left or right edge of the screen when the player turned and, finally, a set of markers on the floor denoting the outside edge of each level. It also incorporated an elegantly designed inventory system, managed by the player and accessed by the Intellivision’s unique disk and keypad controller.

The complex game play and process of character development in Treasure of Tarmin required a significant time commitment on the part of the player, as the Intellivision was incapable of saving the game’s progress. The game’s four difficulty settings were measured in the number of levels required to reach the final treasure, an estimated 5 minutes on the easiest setting, to 5 hours on the most difficult. The memory resources needed to produce Loughry’s two games were significant, which demanded larger cartridges. Cloudy Mountain was designed on a 6 kilobyte cartridge at a time when 4 kilobytes was standard, while Treasure of Tarmin was even larger at 8 kilobytes.

Exploration-based gameplay appeared in many other home console games of the early 1980s. Haunted House (1982, Atari) placed the player in a haunted mansion, searching for pieces of a broken urn. Since the game was comprised of slowly feeling one’s way through the dark by way of match light, the game had no timer and awarded the player for using as few matches as possible. Randomized locations of objects, again, played an important part in the game’s replayability. Howard Scott Warshaw’s Raiders of the Lost Ark (1982, Atari) for the VCS, reenacted the film of the same name and put the player on a multi-screen adventure looking for the location of the Ark of the Covenant. The complexity of the game necessitated an inventory system, as multiple items were often required to advance to new sections. Since the VCS joystick had a limited number of inputs, Raiders of the Lost Ark experimented with the use of two joysticks—one to control the character, the other to select items from the inventory.

A different approach to action and exploration was used in David Crane’s incredible 255 screen game, Pitfall! (1982, Activision). Pitfall! required the player to move between multiple spaces in search of treasure, often backtracking in order to retrieve an out-of-reach item (Figure 5.8). Crane’s design for Pitfall! allowed it to remain challenging for new and experienced players without resorting to difficulty settings or game variations. The game had a unique approach to scoring, as collecting treasures increased score but certain dangers, like rolling logs or falling into an underground tunnel, would erode accumulated points. Other dangers like crocodiles, quicksand, and scorpions resulted in an instant loss of a life. The longer one played, the greater the chance that the score would fluctuate, adding another level of challenge to experienced players. Further, he used a timer set at 20 minutes. This feature allowed newer players, who would presumably lose quicker, the opportunity to explore the large game space and see its vast offerings without being required to hurry through it. Once a player mastered the game’s early challenges and played longer, the timer became an important consideration and created a new source of tension. The unique combination of elements, coupled with sophisticated graphics that many thought were impossible to display on the VCS, made Pitfall! one of the most highly regarded games of the second generation.

FIGURE 5.8 Pitfall! (1982, Activision).

Resource Management Games on Home Consoles

Prior to becoming an Intellivision programmer in 1980, Don Daglow created university mainframe games in the 1970s such as Star Trek, Dungeon and others. Additionally, he designed a number of social studies-themed educational games that he used as a middle school teacher. When Mattel’s management requested an Intellivision game that differed from arcade-style and sports games, Daglow drew on his background to create Utopia (1981, Mattel). The principal gameplay of Utopia was centered on managing an island community’s happiness by building infrastructure and mitigating the effects of natural disasters. It combined active resource gathering—moving a fishing boat around the screen, with long-term strategic planning—building structures that modified elements such as the rate of currency gain, food produced, and population growth. Like many second-generation games one or two players could play the game, each governing their own island. The game’s systems included uncontrollable weather patterns that could help or hinder as well as affordances that created rebellions should the quality of life of the inhabitants drop too low.

Utopia was one of the first “god games,” as it allowed an omniscient player to see all and direct all. The Intellivision’s keypad controller was well-suited for the gameplay: each button allowed the player to build a different structure, a method of interaction that appeared as a graphical user interface in later simulation and real-time strategy games such as Sim City and Command & Conquer (see Chapter 6). It was an immediate success and earned praise as a game type that reinforced Intellivision’s image as a more sophisticated, “intelligent” console.

A similar management-type game, Fortune Builder (1984, Coleco), appeared 3 years later on the ColecoVision (Figure 5.9). One or two players developed land by building infrastructure, residential areas, and commercial spaces while managing a pool of money. The player used a scrolling window to navigate the game space, allowing them to encounter a variety of terrain such as mountains, rivers, and coastlines. Television bulletins occasionally informed the player of severe weather and provided direction for popular and unpopular activities among the city’s inhabitants. Fortune Builder was not as loosely structured as Utopia: players worked toward earning $250,000,000 in a set time limit or raced to reach the goal before their opponent. Like Utopia, however, its design was wholly suited for play at home as the game’s relatively flat difficulty and longer gameplay time would be unsustainable in an arcade context.

FIGURE 5.9 Fortune Builder (1984, Coleco).

The map-like spaces of these games and others of the second generation like War Room (1983, NAP Consumer Electronics) meshed well with the capabilities of the Intellivision and ColecoVision as they utilized tiling. As opposed to drawing each pixel and remembering their individual positions, the tile-based Intellivision and ColecoVision systems created the screen from sets of 8 × 8 pixel tiles. This reduced the amount of information the processor needed to track and allowed for faster game performance. Additionally, artists could create game visuals faster as tiles could be reused to cover areas quickly. Tiling was particularly apparent in the landscapes of Fortune Builder as the mountains and bends in the river were created from the same sets of tiles. Each icon representing improvements on the landscape was also composed of a single tile. Tiling was not exclusive to home consoles as many 2D arcade games such as Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, and Gauntlet also utilized this method of creating graphics. It would also appear in later 2D home consoles of the 1980s and early 1990s such as the Nintendo Entertainment System, Sega Genesis, and others.

Time of gameplay was also significant in translating sports-based games from the arcades to the home. Atari’s coin-op Football (1978), for instance, granted the player up to 3 minutes of gameplay per quarter. Players who wished to play longer needed to add additional coins, which broke up the flow of the game or otherwise caused the player to adopt riskier strategies that would result in a quick score. The game length of Bob Whitehead’s Football (1978, Atari) for the VCS, however, began with five minutes. Realsports Football (1982, Atari) simulated a 15 minute game, with later titles adding more time per play. In addition to football, designers recreated most of the major sports in greater detail by including more of the sport’s dimensions of play; a trajectory that put sports-based games on the path to simulations.

The North American Console Crash

In 1982 the game industry was riding high and expanding rapidly; projections estimated that the industry would break two billion dollars sometime during the year. Atari, itself, represented the majority of the industry, with arcade games, home consoles, and home computers (see Chapter 6). Atari’s competitors also looked vigorous, as analysts predicted a high that would run through 1985. These predictions, however, were based on grossly inflated estimations of worth: the stock of Atari’s parent company, Warner Communications was selling at eight times its earnings, while Intellivision producer Mattel was selling at four times its earnings. In addition to a false perspective of the industry’s worth, management at many game companies failed to respect the process of game development leading to a number of poor business decisions. The North American crash of 1983 was thus a perfect storm of circumstances occurring within a bubble ready to burst.

Perhaps the main factor that contributed to the crash was the attempt by software developers to cash-in quickly by churning out a high volume of games that were frequently substandard and derivative. Companies large and small, many of which had little to no experience in digital games, attempted to find success in a market that seemed to go only in one direction—up. But, as the major console producers lost control over who could publish content on their systems, consumers were forced to wade through an escalating volume of poorly designed or unimaginative games to find quality.

Two high-profile releases by Atari, Pac-Man in the spring of 1982 followed by E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial during the year’s holiday season, added to the problems. Pac-Man was the most popular arcade game in the United States after its 1980 debut. It spawned copious amounts of merchandise, multiple strategy guides, a Top 40 song, and even a Hanna–Barbera animated series. Expectations, thus, were high when Atari announced the game would be available for the VCS in the early spring of 1982. Atari understood the importance of the game in so far as its ability to generate profit, but it failed to take the steps necessary to produce a quality product.

Rather than being assigned to an experienced programmer, the VCS adaption of Pac-Man was put up for grabs and eventually found its way to programmer Tod Frye as his first project. Further, Atari management decided to use cheaper 4 kilobyte cartridges rather than higher capacity 8 kilobyte cartridges, severely limiting the game’s scope. Frye’s adaption, nonetheless, faithfully recreated the rules and game mechanics of Pac-Man, but had little of the game’s feel and beloved visuals: the individually colored ghosts of the arcade version were rendered in identical colors that flickered due to the VCS’s sprite limitations; the sounds and animations were limited and choppy; it contained none of the cut scenes; and the colorful bonus fruit was replaced with a generic square set of pixels identified as a “vitamin” (Figure 5.10). Since Atari expected sales to be significant, it ordered the creation of approximately 12 million cartridges, a figure that exceeded the estimated number of VCS consoles in the United States by a few million. This decision was based on the assumption that the game itself would sell more consoles, similar to what had happened with the VCS port of Space Invaders.

FIGURE 5.10 The VCS Version of Pac-Man (1982, Atari).

The development of E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, was similarly compromised by poor business decisions, the most significant mistakes coming from Atari’s parent company, Warner Communications. Warner, in an attempt to persuade Steven Spielberg to direct films for Warner Communication’s film branch, Warner Studios, agreed to pay Spielberg an exorbitant sum of $21 million dollars for the rights to create an E.T. game. With the deal made, Warner informed executives at Atari that not only must a game based on E.T. be made, but also that it be ready for the 1982 holiday season. Programmer Howard Scott Warshaw had experience producing games, including the acclaimed Yar’s Revenge (1982, Atari) and Raiders of the Lost Ark, but was given just over 5 weeks to take the game from concept to production. Despite this limited time frame, the game was fairly ambitious: an exploration game based on collecting scattered parts of a device randomly distributed through multiple screens in order to “phone home” while avoiding scientists and FBI agents. Each screen allowed E.T. to execute a different power that helped him on his journey. Nonetheless, since development times for most second-generation games typically took a few months, quality testing was skipped and the game shipped in an unpolished state that made it frustrating to play. In particular, the gameplay was disorienting to players as moving from one screen space to another could result in continuously falling into pits. Worse yet, Atari needed to sell a large number of cartridges to recoup the $21 million licensing deal and return a slim profit, leading them to produce 5 million cartridges.

Just as 1982 was a year of intense growth, 1983 and especially 1984 were years of rapid contraction. Although Pac-Man and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial initially made spectacular sales, the gameplay of E.T., in particular, motivated a large number of consumers to return the game. Retailers saw the demand for nearly all console games evaporate and returned their unsold and often unopened merchandise to Atari. Of the 5 million E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial cartridges produced, approximately three and a half million were eventually returned to the company from distributers. Other games were similarly returned. Atari, with a backlog of multiple titles that retailers could not sell, disposed of a majority of the overstock in a Sunnyvale, California landfill. A small portion was sent to a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico, where the dumping was sensationalized in local newspapers and national media, growing in scale over time. The end result was a myth that the Alamogordo landfill received all 3.5 million unwanted copies of E.T. and that the game had single-handedly brought the industry crashing down.

The development and marketing fiasco of Pac-Man and E.T., while extremely damaging to Atari, was not in itself sufficient to cause the market crash. The introduction of affordable home computers, like the 1982 Commodore 64, persuaded many consumers to purchase something with an application beyond game playing (see Chapter 6). Consumer confidence was also steadily eroded as many companies over-promised and under delivered. Mattel released the Intellivision II in 1982, which despite its name, was identical to the original Intellivision except for a number of cost-saving elements that lowered the quality of the product but allowed it to play VCS games via the System Changer add-on. Mattel and Coleco both produced other add-ons that turned their consoles into fully functioning home computers; however, Mattel’s did not materialize until it was too late and Coleco’s “Adam” computer conversion kit did not sell well. Further Coleco had rushed its 1983 Adam computer into production to meet a promised shipping date, half of which were returned as defective.

As sales of home videogame consoles and cartridges declined, many game producers large and small were forced to shut down. Coleco exited the market completely in 1985. Mattel closed its electronics division in 1984, however investors bought the rights to the machine and continued to release games and units until 1990. Nonetheless, the Intellivision would be seen as a minor player in the upcoming era of the Famicom/Nintendo Entertainment System (see Chapter 7). Warner Communications sold the home console and computer division of Atari in 1984 to help finance the company’s value drop and in 1985, the coin-op arcade division was sold as well. Parts of Atari Inc. bounced between various companies around the world throughout the 1980s and 1990s. It continued to produce home video game consoles through the mid-1990s with the Jaguar, but the brand never regained its earlier status. While home consoles took the brunt of the damage from the crash, arcades in the United States too suffered as an estimated one-fifth closed their doors in 1983. Smaller venues such as bowling alleys and movie theaters, however helped keep arcade games in demand through the 1980s and 1990s.

It is important to keep in mind that the crash of 1983 was confined largely to North America. The console industry in the early 1980s was not as developed in other parts of the world, at times resulting in little indication of anything that could be construed as a “crash.” Much of this was due to the greater popularity of home computers in Europe and elsewhere, as they represented a different market and catered to a wider array of gaming preferences. Nonetheless, the fallout created a vacuum that allowed Japanese companies like Nintendo, Sega, and Sony to rekindle the home console market in North America and lead it through much of the contemporary context.