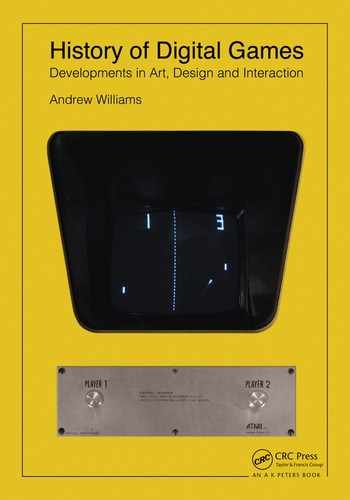

Mechanical and Electromechanical Arcade Games (1870–1979)

Nearly one-hundred years before the first appearances of digital arcade games, both mechanical engineers and artists created games designed to be visually attractive, easy to understand, and difficult or outright impossible to master. These design concepts were conditioned by a business model that centered on making money by having a high volume of customers pay low prices per trial. As such, the games would only be financially successful if play could start immediately and conclude quickly. While impossible to establish the absolute origin of these concepts, they are intimately connected to playing games in public spaces and are best illustrated by carnival games and games played on the midways of fairs. Combined with the very human desire to win or redeem one’s self after failure, these ideas led to some of the most memorable, enjoyable, and profitable gameplay experiences of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This chapter explores the development of many of these ideas and discusses the companies, technologies, and personalities that helped hone a philosophy of game design that widely influenced the major gaming contexts of both the arcade and the home.

The Beginnings of Coin-Operated Amusement

The beginning of coin-operated machines dates to as early as the first century CE when the inventor Heron of Alexandria designed a device that used the force of a dropped coin to trigger a mechanism that dispensed water for purification rituals. While Heron’s design was strikingly forward thinking, the classic coin-operated videogame arcades of the last quarter of the twentieth century relate more directly to the technological and economic changes brought about by the Second Industrial Revolution of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Three major types of coin-operated amusement machines emerged from this period: the first were noninteractive working models that brought kinetic delight to audiences; the second were monetized versions of testing devices designed for use in public spaces; and the third were viewers that allowed individuals to look at a series of two-dimensional (2D) still images, three-dimensional (3D) stereoscopic images, or early motion pictures. The creation of these new coin-op devices illustrated complex changes in the industrialized nations of the late nineteenth century as the public found itself increasingly able to not only spend money, but also spend money on quick bursts of amusement-related activities.

Automata and Coin-Op Working Models

Since the medieval period, European engineers applied the knowledge associated with clocks to create mechanically animated amusement devices called automata. The variety of automata was vast, ranging from mechanical birds that sang songs, to automated devils who made grotesque expressions to congregations of Christians. Over the course of several hundred years, the works became increasingly specialized and elaborate, leading to lifelike recreations of movement and behavior. The production of automata in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by Swiss, German, and French clockmakers was particularly noteworthy, as their creations displayed sophisticated mechanical programming stored on irregularly shaped discs called cams; an early form of read-only memory and a key component of later mechanical amusement devices.

Jacques de Vaucanson created the Canard Digérateur or “Digesting Duck” in 1739 that flapped its wings, ate, drank, and even simulated defecation. In 1785, Peter Kinzing and David Roentgen gifted France’s queen Marie-Antoinette with an automaton that played a miniature dulcimer by actually striking the strings with a hammer, all the while making subtle movements with its head and eyes. Perhaps, most impressive was the Draughtsman-Writer created by Henri Maillardet around 1805, which drew four detailed scenes and wrote three poems in script; two of which were in French, the other in English. This automaton had the greatest amount of programming and memory capacity of any produced of the time, yet it, like the others, consisted solely of gears, cams, and wound springs. Such masterworks of science and invention served as amusements for the wealthiest European nobles. The larger public had relatively little experience with automata until they appeared as a part of magic show acts in the later nineteenth century. The full introduction of these devices to the public, however, came in the form of coin-operated working models.

Working models first appeared in England and then spread to the rest of Europe and the United States. They typically consisted of an animated scene or object, sometimes accompanied by music that created an audiovisual experience. One of the earliest designers of working models in the United States was William T. Smith who created The Locomotive in 1885 (Figure 1.1). Inserting a coin made the miniature locomotive come to life as music played while pistons drove the wheels and levers pulled a string to ring the engine’s bell. Although entirely made by hand, the battery-powered model was produced in large quantities that allowed for wide distribution. Fitting the device’s theme, Smith’s working model was commonly placed in railroad stations to maximize exposure to a constant stream of potential customers.

FIGURE 1.1 The Locomotive, 1885 by William T. Smith. (Courtesy of National Jukebox Exchange, Mayfield, New York, www.nationaljukebox.com)

Similar examples from Europe, such as coin-operated singing birds created by French automaton designer Blaise Bontemps, attracted people who frequented public spaces and emerging amusement centers. In addition to machines and animals, working models also featured elaborate scenes of animated puppets. In England, for instance, the Canova Model Company produced a number of working models employing sensationalism that illustrated scenes of drama and horror, much like British “penny dreadful” novels. One such example was The French Execution (1890), which showed the execution by guillotine of a convicted criminal. Another working model by Canova Model Company showed animated figures suffering from opium addiction while being visited by horrific characters. Despite a sharp decline of popularity in the early 1900s, working models were produced well beyond the 1950s, with one of the most popular being the life-size animated “grandmother” or “gypsy” fortuneteller who consulted crystal balls or tarot cards before dispensing a written fortune.

At the same time that automata were fitted for coin operation, a similar phenomenon was happening to popular pub and saloon games. Although slot machines and other gambling games were by far the most popular types of machines in these establishments. Pubs and saloons also featured games that promoted competition or facilitated social interaction and spectatorship. The majority of these machines measured the results of lifting, pushing, pulling, gripping, and punching. For example, the P.M. Athletic Company’s Athletic Punching Machine (1897) featured a large padded area designed to measure an individual’s punching power while the early twentieth century Perfect Muscle Developer by Mills Novelty Co. used a plunger resisted by a large spring to measure lifting ability (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 Electricity is Life, 1904 Mills Novelty (a) and Perfect Muscle Developer, early twentieth century C Mills Novelty (b). (Courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, Maine, www.jamesdjulia.com)

Regardless of test type, these machines shared several characteristics: sturdy materials designed for repeated use and decoration representing the rich aesthetic vocabulary of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The Perfect Muscle Developer, for instance, used heavy iron in its plunger and platform where the competitor stood while the rest of the device’s wooden exterior was embellished with decorative motifs and an elaborate image of the trademark Mills Novelty owl icon. The most important and prominent feature of nearly every strength tester, however, was its display. Displays measured effort numerically, providing an unambiguous, quantifiable, and comparable assessment of performance. They were also typically the largest part of the machine, making the readout visible to not just the user, but onlookers as well; a reflection of the social environment these devices inhabited. The competitive nature of these devices was explicit as the display of the Perfect Muscle Developer featured phrases like “Not so Good. Use me More” for a low score of 100 and “Great Stuff BIG BOY!” for a high score of 900, giving the competitor feedback on their performance even if not competing in front of a crowd. In addition, the machine continued to display the attempt’s score until a new coin was inserted, providing motivation to the next challenger to leave a higher score.

In addition to the various forms of physical strength testers, devices that measured health as a reflection of strength were also extremely popular. Scales measured a person’s weight, spirometers measured lung capacity, and machines that administered electric shocks as a “cure all” for headaches, rheumatism, and “all nervous disorders” appeared in cigar stores, post offices, drug stores, hotels, and saloons. Important in the promotion of many of these testers was the “scientific” basis for their health benefits, regardless of actual scientific proof. For example, the 1904 Mills Novelty Co. Electricity is Life boldly proclaimed “Electricity, the Silent Physician. Treats all forms of muscular ills. Good for the nervous system too.” Here as well, the large dial contained messages for scores based on how long the person held on to the shocking machine; “Electricity if properly applied will benefit any one” was shown for a range of the lowest scores while “Exceptionally fine condition of the entire system” indicated the highest score (Figure 1.2). Spirometers that measured a user’s lung capacity followed similar competitive health formats. As an extra incentive, many of these health-based testers returned the spent coin for exceptionally high scores of “healthiness.”

A related form of tester was those that measured a person’s accuracy with projectiles. Since at least the 1880s, several companies produced gun games for amusement purposes and used virtually anything for projectiles: coins, ball bearings, pellets, gumballs, and even live ammunition. All of these early gun games used realistic looking rifles or pistols for controls. They sometimes also featured highly detailed animated environments, an antecedent of the later electromechanical and digital gun games of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. A surprisingly advanced early gun game was the English-made Electric Rifle of 1901, which used wires and a sophisticated alignment system to send signals from a pedestal-mounted gun to a target area that, when properly aligned, caused bells to ring, figures to animate, and bullet holes to appear. More common, however, were small countertop-based shooting games called trade stimulators that distributed cigars, candy, or other small consumables. Figure 1.3 shows an early twentieth century gun game trade stimulator that used a penny as a projectile. A perfectly aimed shot sent the coin through the bull’s eye where it rang a bell and returned the coin. More likely, however, the shot missed, resulting in a gumball for the player and a coin for the machine’s owner.

FIGURE 1.3 Simple early twentieth century gun game trade stimulator. (Courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, Maine, www.jamesdjulia.com)

Coin-Op Viewers at the Turn of the Century

Even more technologically sophisticated than working models or testing devices were the coin-operated amusements created by American inventor Thomas Alva Edison. Known as the “Wizard of Menlo Park” for his work in creating the incandescent light bulb, methods of distributing electricity to buildings and x-ray-related technologies, Edison’s foray into coin-operated entertainment began with the invention of the phonograph. Edison’s original intention was to create a machine to record business meetings. This concept, however, received a lackluster reception. One of Edison’s investors, however, experimented by adding listening tubes and a coin slot to the phonograph. For a nickel, the user could hear a recording of music, speeches of public figures, or dramatic narratives filled with sound effects. Thus, the phonograph was brought in line with the growing number of late nineteenth century mechanical and electromechanical novelties in train stations, hotel lobbies, and resorts.

Edison’s influence on the coin-operated industry was more profound with his next product, the Kinetoscope, prototyped in the late 1880s and put into production in 1894. Created by Edison’s assistant, William Dickson, the Kinetoscope was capable of playing motion pictures from a strip of 35 mm film run between a peephole and a battery-powered light bulb. A user could watch 30–40 second movies of boxing matches, circus performers, or historical reenactments. Each machine was loaded with a different film produced at Edison’s Black Maria Film Studio in West Orange, New Jersey.

Dedicated amusement spaces called Kinetoscope parlors first appeared in New York and spread to Chicago, San Francisco, Atlantic City and abroad to London and Paris where they were located in central business districts. To capitalize on Edison’s reputation as a producer of technological marvels, many of the Kinetoscope parlors used his name on banners, named their parlors after him, and even incorporated Edison’s likeness into decorative statues. Kinetoscope parlors, often decorated in the high style of the time, catered to the upper tiers of society. The interior of Peter Bacigalupi’s Kinetoscope parlor in San Francisco, for example, featured a flamboyant peacock made of feathers and light bulbs, floor-to-ceiling wallpaper and lighting fixtures powered by gas and electricity—a luxury in 1895 that ensured continual lighting (Figure 1.4). The initial model of the Kinetoscope was not equipped with a coin slot. Patrons paid an admission fee and viewed as many of the short film segments as they desired, served by a staff of well-dressed attendants operating the machines. Like other devices, coin slots were quickly incorporated, reducing the need for as many attendants.

FIGURE 1.4 Patterned interior of Edison’s Phonograph and Gramophone Arcade in San Francisco, California. (Courtesy of U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park.)

The Kinetoscope parlor was more than film; it often contained vending machines and a full array of other Edison gadgets including the phonograph and even x-ray machines that visitors used to view the bones in their hands. When it was realized how harmful x-rays actually were, as no shielding was used in any of the devices, the novelty x-ray machines were promptly removed. The Kinetoscope parlor helped create the concept of an “arcade” as a space of coin-operated amusement devices as seen in the proper name of Bacigalupi’s Kinetoscope parlor: “Edison’s Kinetoscope, Phonograph and Gramophone Arcade.” From this point on, it became increasingly more common to see the word “arcade” in the titles of amusement spaces.

A Gathering of Games and Amusements at the Penny Arcade

Since many British and American games of the late nineteenth century cost a penny to operate, “penny arcade” became a common term to describe the increasingly frequent clustering of low cost amusement games and devices. In the United States, permanent penny arcades first appeared on the East Coast in the early 1900s, especially in New York City, as the games needed a large audience to remain profitable. In England, permanent penny arcades were relatively rare until the 1920s as it was far more common to have machines placed sporadically along the piers of seaside resorts outside of London.

Like Kinetoscope parlors, penny arcades prominently featured motion picture machines. Edison’s Kinetoscope had waned in popularity by the early 1900s, replaced by a new coin-operated movie viewer, the Mutoscope, created by Kinetoscope inventor and former Edison colleague William Dickson. This penny arcade “peep show” device was crank-powered and spun a series of sequential images on paper past an eyepiece. Cheaper to manufacture and maintain, with larger and clearer images, it was able to outperform Edison’s Kinetoscope. The Mutoscope had a robust international presence, with business relations in the United States, England, France, and other European countries. The model most frequently associated with the penny arcades was the 1901 “Iron Horse” that featured an abundance of decorative elements including a “clam shell” design on the viewer’s side (Figure 1.5). Like the back glass and cabinet art of later pinball and videogame arcade machines, these aesthetic flourishes, along with electric lights and patterned wallpaper in the arcade’s interior, were meant to create spaces of excitement that could lure potential customers off the street.

FIGURE 1.5 “Iron Horse” model Mutoscope (1901, International Mutoscope and Biography Company). (Courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, Maine, www.jamesdjulia.com)

By 1907, penny arcades in the United States had narrowed their focus and provided less film-related amusements. After early filmmakers began to exploit the artistic and mass entertainment potential of film, showings moved out of peep show parlors and into specialized spaces designed for projection to large audiences. Despite competition between penny arcades and early movie houses, the penny arcade was still dominated by novelty viewing devices. According to the suggested layout of penny arcades in the 1907 Mills Novelty Company catalog, penny arcade owners were to set up as many as 25 stereoscopic peep show machines but carry only 15 other coin-op devices such as strength testers. Images of penny arcades from the period show row upon row of Mutoscopes, Quartoscopes (which showed non-animated 2D or 3D images), and other coin-operated viewing machines, with a few punching, lifting, and fortune-telling machines sprinkled in between.

Envisioned as spaces for families, with candy machines that randomly chose prizes for children, the ideal customers at early penny arcades were young men, which resulted in peep-show viewers with sexually suggestive titles like “For Men Only” and “Those Naughty Chorus Girls.” While titillating in title, what was actually delivered (the occasional nudes not withstanding) often failed to live up to imagined expectations.

Sport-Based Games and the Roots of Digital Game Genres

In addition to viewers and testers, coin-op manufacturers also produced games based on organized sports. Early sports-based coin-op machines combined the elements of target shooting and strength testing games with detailed environments and animated characters seen in working models. This signaled a different approach to thinking about interacting with games as the player did not directly compete in the task, but did so through a surrogate entity that represented the player’s presence and actions in the game space; a concept known as the avatar in digital games. A significant number of these sports-based games were intended for two players, a design feature of paramount importance for games used in public social spaces. Many machines also featured a large amount of glass, allowing crowds of spectators to enjoy the game as well.

Like other early coin-op devices, England was a major center for the manufacture and export of sports-based arcade games in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The London-based Automatic Sports Company manufactured a number of games based on British sport such as Yacht Racer (1900) and The Cricket Match (1903). Because of technical and practical limitations, these games did not recreate all of the dimensions, rules, and interactions of any one particular sport; rather they were abstractions of the sport’s basic gameplay experience. The Cricket Match, for instance, focused on the batting and pitching portions of the game. The batting player attempted to hit a pitch into any one of a number of holes in the playfield, the most difficult of which returned the spent penny to the player. Administering a reward for a skilled or lucky performance, as seen in The Cricket Match, was common in other English arcade machines of the time as well (Figure 1.6). Considered in light of the game-based trade stimulators discussed earlier (Figure 1.3), the boundaries between coin-op vending machines, arcade games, and gambling machines were anything but fixed in the early 1900s.

FIGURE 1.6 An English “Climbing Fireman” coin-op game from the 1920s. (Courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, Maine, www.jamesdjulia.com)

Full Team Football, created by the London-based Full Team Football Company in 1925, featured a standard 11 on 11 game of soccer with red and blue players grouped at the forward, midfield, defender, and goalie positions. A brightly colored background of seated spectators completed the illusion. In a similar setup to a contemporary foosball table, each group of players was controlled by one of three levers that allowed them to kick a ball around the field until one side scored a goal. Even with the players fixed in place at each position, the game was able to recreate frantic ball movements by using a ridged field that could redirect the ball in an unpredictable manner. When a goal was scored, the game was finished and no payout was received.

Although England was the main manufacturer of arcade games throughout the early 1900s, penny arcades and their machines were more popular in the United States. By the late 1920s, American manufacturers were producing games in larger numbers, some of which were adaptions of English games. In 1926, the New York-based Chester-Pollard Amusement Company was granted the right to distribute Full Team Football in the United States and renamed it Play Football (Figure 1.7). This represented the beginning of a new line of games in the United States. American advertising of Play Football carried taglines like “Something New at Last,” implying that the coin-op amusement industry was hungry for new ideas. The game, although similar in form to its English predecessor, was greatly modified in operation as the player pressed one, and only one lever to control the kicking motion of the figures. Although this greatly reduced the ability for the player to make meaningful gameplay decisions, the reduction in moving parts lowered the cost to manufacture the game and potentially meant less maintenance over its lifetime. The game, nonetheless, saw wide distribution. Its frantic and competitive matches made it popular in penny arcades.

FIGURE 1.7 Play Football (1926, Chester-Pollard Co.). (Courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, Maine, www.jamesdjulia.com)

NON-SPORT PENNY ARCADE GAMES

Not all competitive coin-op games were based on specific sports, as seen in the English “Climbing Fireman” arcade cabinet from the 1920s (Figure 1.6). The game required each player to insert a coin and furiously turn the machine’s dial to ascend his or her fireman as fast as possible to reach the top of the ladder first. The winner’s fireman signaled a bell and triggered the machine to return one of the coins, presumably to the winner. The visual details in the firemen’s clothing and building’s curtains as well as the animated figures show common elements between working models and early arcade games.

The Chester-Pollard Amusement Company followed the success of Play Football with other sport-based games such as Play the Derby (1929). Play the Derby, featured a miniature horseracing field complete with track, trees, buildings, and railings, painted in bright colors. Much like the controls in the Climbing Fireman game (Figure 1.6), Play the Derby used a hand crank to drive each player’s horse around the track in a two-lap race. To prevent the game from devolving into a mere competition of spinning the handle the fastest, the game’s mechanical engineers devised a clutch that slipped if a player spun too fast, resulting in a horse that came to an abrupt stop. This encouraged not only a more interesting form of gameplay, as players had to contend with the crank’s speed threshold, but also helped ensure that the machine’s mechanism would receive less physical abuse from overexcited players.

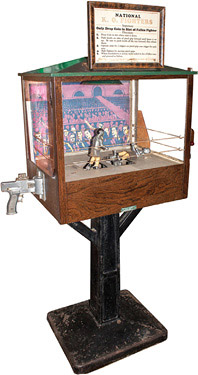

Penny arcade game design in the 1920s and 1930s was also influenced by the popularization of radio. The technology for radio developed throughout the 1800s, but the medium came into proper form during the 1920s as the number of stations (and thus radio programs) grew at an exponential rate. The broadcasts that drew the largest crowds and most captivated the public’s interest were those featuring live sporting events, particularly boxing matches and baseball games. The 1926 boxing match between the heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey and challenger Gene Tunney, and its rematch a year later, was one of the most anticipated and listened to broadcasts of the day, carried on 74 radio stations and drawing an estimated crowd of 15 million listeners. Although first appearing in late 1800s England, American companies continuously created boxing games from the 1920s to the 1970s in an attempt to capitalize on the continued excitement generated by the real-life matches. Most used similar formats of small, articulated figures maneuvered by players in a miniature-boxing ring. Rather than tabulating points for each punch landed, as in the actual sport of boxing, the game concept attempted to recreate the most dramatic portion of the match: the knockout punch to the chin. This proved pragmatic for the design of the device, as it provided a decisive and exciting signal of victory. In K.O. Fighters (1928, National Novelty), the players moved two boxers in and out of punching distance through pistol-grip handles that allowed for individual control of the right and left arms (Figure 1.8). The player who connected a punch to a trigger on their opponent’s chin caused the defeated player’s boxer to fall to the mat.

FIGURE 1.8 Knock Out Fighters (1928, National Novelty). (Courtesy of National Jukebox Exchange, Mayfield, New York, www.nationaljukebox.com)

Baseball, however, was more difficult to execute in a coin-operated arcade game due to the complexity of the sport’s rules. Since the sport of baseball only allows the team at bat to score points, the majority of designers of arcade games chose to focus on hitting the ball. George H. Miner, an automobile mechanic working for the Amusement Machine Corporation of America, created the highly sophisticated electromechanical All-American Automatic Baseball Game (1929) which replicated nearly all the rules of baseball related to pitching, batting, and scoring runs. The player, as the batter, attempted to hit a ball bearing past basemen and outfielders to the stadium wall where it fell into various chutes that counted as a single, double, triple, or home run. The game’s impressive pitching system allowed the mechanically controlled pitcher to actually throw the ball bearing a short distance before it rolled to the batter. An irregular-shaped cam caused the pitcher to subtly change direction before each throw, giving a great degree of variety and making pitches seem unpredictable. A series of hidden slots behind the batter registered an un-hit bearing as either a ball or strike and then computed it so that three strikes converted to an out, three outs ended the game, and foul balls counted as strikes. As a final aesthetic flourish, the game’s umpire, located behind the pitcher, gave a signal for each ball or strike by raising his left or right arm. The rights to Miner’s game were eventually purchased by the influential pinball and arcade game designer, Harry Williams, who modified it to include a display that automatically updated the positions of men on base and cleared the bases in the instance of a homerun or final out. Williams’ game was released to coincide with the highly anticipated 1937 World Series between the New York Yankees and New York Giants, in a game appropriately called 1937 World Series (1937, Rock-Ola) (Figures 1.9 and 1.10).

FIGURE 1.9 1937 World Series (1937, Rock-Ola). Note the rounded edges of the case and decorative stripe that shows the influence of the Art Deco design movement. (Courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, Maine, www.jamesdjulia.com)

FIGURE 1.10 The Pitcher was able to throw the ball bearing as far as the black padded circle, after which it rolled to the batter. (Courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, Maine, www.jamesdjulia.com)

It may be tempting to create a connection between Miner’s 1929 baseball game and the gameplay of pinball, with the bat serving as a proto-flipper and Williams’ involvement as one of the preeminent pinball designers of the twentieth century. While they do share some similarities in mechanical elements, the state of the game of pinball was vastly different. The game of pinball emerged in the late 1920s and early 1930s after undergoing a number of changes from its ancestor, the eighteenth century French game, bagatelle. Bagatelle was played on a rectangular felt-covered table and used a cue stick to sink a ball into a pattern of holes at the opposite end of the board. The slight incline of the table caused any balls that missed their target to roll back down to the table’s base. To enliven the game, the playing surface frequently included small upright nails that randomly redirected the movement of the ball. This game proved popular among upper class members of French society and was eventually brought to the United States where it was miniaturized for use on countertops in saloons and other places.

The game in its miniature form remained essentially unchanged until 1871 when the American, Montague Redgrave, filed a patent entitled “Improvements in Bagatelle” which replaced the miniature cue stick with a spring-loaded plunger and added several obstacles to the playing field. These features included small gates that slowed ball momentum, cups that funneled the ball to different areas, and bells that rang when game balls collided with them. From the standpoint of gameplay, Redgrave’s introduction of the spring-loaded plunger promoted accessibility: by equalizing skill across players, the fine art of using the miniature cue sticks was no longer necessary. The game’s inclusion of bells created not only a multisensory gaming experience, but also an unambiguous indication of point score.

Interest in bagatelle or “pin games,” as they grew to be known, came and went until a major surge of interest occurred in the 1920s and 1930s, the same period that saw the expansion of game offerings in arcades. One of the first successful pinball game designers of the period was David Gottlieb, a man with a background in the design of carnival games and the exhibition of film. Using this experience, he founded D. Gottlieb & Co. in Chicago, which began by manufacturing various amusement devices such as grip testers and shooting trade stimulators. Turning his attention to pinball games, David Gottlieb saw success with Baffle Ball (1931), a completely mechanical game that combined a brightly colored playfield with an interesting placement of pins and cups. Costing a penny for seven to ten shots with steel balls, the player needed to gauge the amount of force used to pull back the lever and direct the balls to the high-scoring areas. Balls that did not make it into one of the four main scoring cups or the coveted “Baffle Point” cup, rolled down to the bottom of the board. Gottlieb, like many other early pin game designers, understood the probability of the ball reaching any one area of the board. As such, the game’s highest scoring areas were located in the places least likely to intersect with the path of the ball. Even with practiced use of the plunger, the pins in the playfield randomly redirected the rolling ball.

Like most games of the early 1930s Baffle Ball did not automatically tabulate score; instead, points were counted manually as the balls remained in their scoring areas after play finished. In this way, the previous score was displayed as a challenge to the next player much like that of strength testers produced 30 years earlier. When the next player inserted a penny into Baffle Ball, the balls would then fall through a series of trap doors, clearing the score. Every game was thus different and often concluded with the unfulfilled desire of reaching the high score targets or beating the previous score. Gottlieb helped popularize the game of pinball in the United States, producing 400 machines a day at peak, and strengthened the presence of coin-operated games (Figure 1.11). Although not explicit, the largely random path taken by the ball’s descent made early pin games ideal for gambling as location owners created game rules that existed outside of those contained within the device itself. This helped pinball games collect pennies and nickels even in the midst of America’s Great Depression.

FIGURE 1.11 Five Star Final (1932, Gottlieb & Co.). The game used the same design philosophy of Baffle Ball as it placed the highest scoring cups in the most difficult to reach areas and left the balls in place until a new coin was inserted. Five Star Final also shows the variety of playfield designs as it was based on a figure of eight. (Courtesy of James D. Julia Auctioneers, Fairfield, Maine, www.jamesdjulia.com)

A New Emphasis on Art and Design

As the pinball industry grew in both the United States and Europe in the 1930s, the need to gain attention in an increasingly crowded field pressured designers to add new, and sometimes unusual, gameplay features. In addition, artists played an increasingly important role by enhancing playfields with colorful images and characters that distinguished the games from one another. An example of the interplay between new game design and art can be found in Rock-Ola’s World’s Fair Jigsaw (1933), an entirely mechanical game that, as its title suggested, featured a colorful jigsaw puzzle of the 1933 World’s Fair fairgrounds. Sinking the ball into various holes in the playfield allowed the player to accumulate points and caused the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle to flip over one by one, or if lucky, to fill in an entire row. Special holes also flipped random pieces or modified the score by doubling the value of points. Completing the puzzle was extremely difficult: the player was given 10 balls to flip 20 pieces, each ball had to be fired with enough energy to circle the entire table almost one and a half times and the pins, springs, and gates dotting the playfield effectively removed any amount of control by the player.

Another novel mechanical pinball game by Rock-Ola, was World’s Series (1934). A similar design to World’s Fair Jigsaw, the playfield was divided into upper and lower spaces and required the ball to be shot completely around the board before entering the pin-studded playfield. The board’s center had a set of channels marked strike, out, ball, or hit. As in the rules of baseball, the game’s complicated mechanisms were able to convert three strikes into an out and four balls into a walk through weight sensitive trap doors. After three outs, the game was over. A ball that went through the channel signifying a hit would fall into the lower portion of the board, which was decorated as a brightly colored baseball diamond. Here the ball was caught in a pocket and rotated in a predetermined sequence, signifying anything from a base hit to a home run. “Runners” who made the trip around the diamond were ejected at the end, clearing the bases and falling into a slot that displayed the number of runs. The design of the playfield assured it was much more likely that the jostled ball would result in an out rather than a hit. Thus, player control in both World’s Series and World’s Fair Jigsaw, like all pre-World War II pinball tables, was minimal at best.

New technologies also helped produce novel game designs for pinball, the most significant being the adoption of electricity in the 1930s. Solenoid-powered kickers shot the ball out of holes and decorative cannons, score totalizers provided unambiguous tallies of points, and Nick Nelson created the first bumpers in the appropriately named, Bumper (1937, Bally). But perhaps the most influential and industry-shaping ideas in pinball came from Harry Williams. Harry Williams (1906–1983) known for the design of innovative features in pinball and for designing arcade machines like 1937 World Series (1937, Rock-Ola), had a degree in engineering and professional experience as a commercial artist. Williams began his game design career refurbishing pinball machines by reconfiguring the arrangement of pins in the playfield. In addition to founding three companies, one of which eventually became Williams Electronics, Harry Williams’ expertise in game design allowed him to work with some of the largest amusement machine companies of the twentieth century, spreading his designs and innovations throughout the entire pinball and arcade game industry. Williams was the first pinball designer to use electricity, creating the “kick out hole” which allowed the ball to fall into a hole and be kicked back into the playfield by a solenoid-powered plunger, a revolutionary idea that was instantly adopted by other designers.

Harry Williams’ influence was also seen in the “tilt” mechanism that prevented players from cheating. Since pinball games were largely chance-based, players created strategies such as hitting or nudging the table to change the course of the ball’s path or lifting the table end to put spent balls back in play. Pinball game designers were largely aware of this and devised a number of anti-cheat methods such as making scoring pockets deeper or weighing the machine down with sandbags. To combat cheating in his games, Harry Williams experimented with a number of design ideas, including placing nails on the bottom of machines. Williams, however, eventually devised the electromechanical “pendulum tilt” in 1935, which consisted of a weight at the end of a rod surrounded by a metal ring. When shaken or jostled too hard, the pendulum swayed and made contact with the ring, creating a circuit and triggering a mechanism that prevented score bonuses or halted gameplay depending on its configuration. Williams’ tilt mechanism was widely adopted and became the standard anti-cheat device in pinball machines at a time when pinball’s expansion appeared limitless.

As discussed earlier, payout for high scores was a common and informal practice between the player and the pinball machine’s owner, as it increased a game’s earning power and skirted the label of gambling. This charade came to an end when manufacturers made gambling functions explicit by introducing payout pin machines in the mid-1930s. Games like Tycoon (1936, Mills Novelty Co.), for example, featured a typical bagatelle-style playfield with seven slots at the board’s bottom. The gambling component came in the form of betting on which slot the game’s single ball would land. If the ball passed through certain gates, it would increase the amount of payout. This single ball gameplay was common among payout pin tables.

Concerns about gambling, meanwhile, swept across the United States resulting in a heavy crack down on all forms of chance-based amusements. During the 1930s and 1940s, Los Angeles, New York, and even Chicago, the center of the US coin-operated industry, enacted severe restrictions on slot machines, payout machines, and regular pinball machines. The situation was further complicated as non-gambling pinball machines in the 1930s began offering a “free replay” or “free game” for players who reached a specified score threshold. This concept was widely adopted and allowed a skilled or more likely, lucky player, to play another game. Pinball was implicated in the gambling crackdown not only for its informal payout practices and heavy reliance on randomized gameplay, but also for this ability to win a free game, as this was considered something of value.

In 1941, at the request of Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, the Commissioner of Investigation in New York City drafted a report entitled “Operation of Pinball Machines in the City of New York.” In its summary, the report stated, “…pinball machines serve no useful purpose and are inherently detrimental to the public welfare. Fundamentally, the operation of the machines in this city presents the same problems as those formerly presented by slot machines.”* As a result, pinball machines in New York City were seized and publicly destroyed by sledgehammer-wielding police as well as Mayor LaGuardia himself, the shattered machines dumped over the sides of boats and barges into the Atlantic Ocean. A patchwork of pinball-related laws spread across cities throughout the United States, ranging from specific requirements that balls had to be rolled by hand instead of being launched by plunger, to a ban of the game outright. In spite of it all, pinball machines still operated in many places, as anti-pinball laws were generally only lightly enforced.

Postwar Mechanical and Electromechanical Game Design

During World War II, many game manufacturers ceased production and joined others in the conversion of their facilities to the production of war materials. Those that did produce games were forced to rely on used parts from prewar games, as new parts were virtually impossible to acquire. Innovation in game design slowed, but existing types saw sudden changes in theme and meaning. British and American shooting galleries, pinball games and trade stimulators sported bright national colors and featured images that dehumanized leaders in Germany, Japan, and Italy, motivating players to humiliate or otherwise destroy them. By late summer of 1945, with the war in Europe and the Pacific concluded, American game companies picked up almost immediately where they had left off, rekindling the coin-op industry. While the American coin-op industry bounced back quickly, the European and East Asian industries were not able to reestablish their momentum until the later 1940s and 1950s. Nonetheless, in the 25-year period after World War II, arcade games of all genres largely transitioned from mechanical to electromechanical operation.

One feature that saw expanded use in postwar electromechanical games was the timer. Timed gameplay helped to even out the rate at which a machine could collect coins, as novice and skilled players played for predictable periods of time. This feature was applied to several existing game genres such as target shooting games like Captain Kid Gun (1966, Midway Manufacturing Co.) and boxing games like K.O. Champ (1955, International Mutoscope Reel Co.) (Figure 1.12). In each case, the experience of gameplay became more stressful and exciting; players were required to not only complete a challenge, but also do so within a limited period of time. The presence of the timer in K.O. Champ, in particular, effectively created a different game as each player was given a minute to score as many knockouts as possible. This led to more frantic matches of flailing shots to the opponent’s chin as opposed to the one-hit knockout boxing games produced 30 years earlier (Figure 1.8).

FIGURE 1.12 K.O. Champ (1955, International Mutoscope Reel Co.). (Courtesy of National Jukebox Exchange, Mayfield, New York, www.nationaljukebox.com)

Driving and Racing Games after World War II

Driving was highly popular in arcade games in the postwar period. Particularly in the United States, the act of driving became a potent symbol of adventure, status, and recreation as families engaged in summer driving vacations and drive-in movie theaters saw their greatest popularity. From the 1950s through the 1970s, coin-op game manufacturers produced a significant number of vehicle-based amusements with timed gameplay operated by steering wheels and pedals. Initially, racing was not a widely implemented concept. More common were games that purported to measure a player’s safe driving skills through their ability to react to changes in the road or the playfield; the better the driver, the higher the score.

The array of technologies used to create the experience of driving was impressive. From 1954 to 1959, Capitol Projector Corp. used film projection of recorded driving footage in various versions of Auto Test. More a simulator than a game, Auto Test awarded the player for making proper driving decisions like avoiding collisions and maintaining the speed limit. Failure to perform these actions resulted in a loss of points. In Genco’s Motorama (1957), the player directed a detailed model car to perform U-turns, parking maneuvers, and other driving exercises in an environment resembling a parking lot in the city. Players of Williams Electric’s Road Racer (1962) controlled a model car suspended over a rotating drum with images of a winding road; the objective was to follow a set of metal studs embedded in the road to gain enough points to be considered a “perfect driver” by the machine (Figures 1.13 and 1.14).

FIGURE 1.13 Road Racer, (1962, Williams Electric Mfg. Co.). In order to view the rotating drum, the player needed to look down into the machine. (Courtesy of Musée Mécanique, San Francisco, California, www.museemecaniquesf.com)

FIGURE 1.14 Game space over a rotating drum. (Courtesy of Musée Mécanique, San Francisco, California, www.museemecaniquesf.com)

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, game designers added more tension and enlivened the gameplay of driving by adding proper racing elements and representing speed in more sensational ways. Chicago Coin’s Speedway (1969) and Motorcycle (1970) featured an endlessly curving racetrack populated by six other rival vehicles moving at different speeds (Figure 1.15). Although avoiding accidents was a significant part of the game, going as fast as possible was even more important as the longer one drove, the more points they earned. Both Speedway and Motorcycle used a method of producing graphics based on shining light through a series of translucent animated discs. The final image seen by the player was projected on a screen using mirrors to create a pseudo-3D perspective.

FIGURE 1.15 Motorcycle (1970, Chicago Coin). Note the distortion of the otherwise round disc caused by the projection technique. (Courtesy of Arcadia, McLean, IL, www.vintagevideogames.com)

One of the most sophisticated racing games of the electromechanical era was Road Runner (1971, Bally). In Road Runner, the player controlled a model car with a steering wheel and accumulated points for passing other cars in a vast, three-lane space that appeared much larger than the game’s cabinet. If the player’s car collided with another on the track, it would tumble end over end through the air and reset on a starting strip outside of the main lanes, where the player could not score points. The combination of timer and non-scoring starting strip encouraged the player to go as fast as possible in order to accumulate maximum points, a marked difference in gameplay from the driving games produced 20 years earlier.

From a technological standpoint, the game space of Road Runner was made possible by a vertical playfield consisting of model cars on conveyor belts mirrored into position. This allowed the player to see a much longer game space than appeared possible from the cabinet’s outside. In addition, the player’s car and rival cars occupied different places within the cabinet and used mirrors, again, to create the illusion of one racetrack. A sensor tracked the player’s car movement and was able to detect if any collisions happened, triggering a mechanical arm to spin the car.

Missile-Launching Games in Japan and the United States

Japan was a vastly different place at the conclusion of World War II as the United States installed permanent military bases and businessmen from around the world moved to Japan looking for new markets. As a result, Japan witnessed different models of behavior, attitudes, habits, and patterns of recreation. The aftermath of the war also saw the creation of a number of major Japanese companies such as Sony, which initially specialized in telecommunications equipment. The combination of these complex and interwoven factors contributed to the “economic miracle” that was Japan in the 1950s and 1960s. It is from this postwar period that significant aspects of Japan’s gaming industry originated.

At the opening of the 1950s, numerous vending machine companies were founded or moved to Japan with the intent of catering to the presence of American soldiers: in 1951, American entrepreneurs Marty Bromley, Irving Bromberg, and James Humpert moved their Hawaii-based coin-op company Service Games (previously named Standard Games) to Japan to provide US bases with various types of vending and slot machines; the Taito Trading Company, founded in 1953 by Russian businessman Michael Kogan, imported jukeboxes as well as other vending machines in Tokyo; and American David Rosen established Rosen Enterprises in 1954, which imported coin-operated photo booths that soldiers used for making ID cards. Starting in the mid-1950s, Rosen Enterprises began importing used arcade games from the United States into Japan, creating the first vestiges of Western-style arcade spaces. By 1960, arcades appeared in major cities all over the country, a sign of the growing demand for leisure activities among the population of Japan. The competition between Rosen Enterprises and Service Games eventually led to a merger in 1965. This new company was headed by Rosen and named Sega, a shortened version of Service Games.

The first arcade game produced under the Sega name was Periscope (1966). Using a mock-up submarine periscope, the player launched torpedoes at sets of model ships powered by a motorized conveyor belt. A series of lights that sequentially turned on and off represented the path of the torpedo to its target. The machine played an explosion sound effect when a ship was hit and flashed a bright red light across the background. The simplicity and fun of Periscope made it immediately successful, as it became the first Japanese game imported to the United States.

Periscope represented a larger trend in the late 1960s and 1970s of missile-launching gameplay. Most of the games featured several postwar electromechanical game design elements already discussed; timed gameplay and vertical playfields that used mirrors to create an artificial sense of depth. The games, expressed in submarine or land-based turret themes, used the basic concept of a shooting gallery but restricted player movement to the lateral plane. This forced players to carefully time their shots against the moving targets since the player had to wait a few seconds between each shot. Several turret-based missile-launching games like Sega’s Missile (1969), created the illusion of missile movement by using film projection on the backdrop (Figure 1.16). The player rotated a brightly lit missile left and right, waiting for proper alignment against a constant stream of planes flying overhead in different formations. Once fired, the light in the missile tuned off and a missile in flight was projected receding into the background, creating a convincing illusion. In the United States, Midway Manufacturing became a major producer of several submarine-themed missile-launching games like Sea Raider (1969), Sea Devil (1970), and Submarine (1979), in addition to land-based turret games like S.A.M.I—Surface to Air Missile Interceptor (1970).

FIGURE 1.16 Missile (1966, Sega). (Courtesy of Arcadia, McLean, IL, www.vintagevideogames.com)

By the mid-1970s, pinball machines had changed markedly from those produced in the 1930s, and were for all practical purposes, a different game. Pinball’s playfields became more colorful and complicated, while back glass art displayed the work of numerous comic book artists and tallied the game’s score as targets were hit. Solenoid-powered flippers first implemented in Gottlieb’s 1947 Humpty Dumpty and refined over the decades, allowed the player more control over the ball, a feature entirely lacking in earlier pinball tables (Figure 1.17). The idea of “winning” a free game was replaced by the “add-a-ball” game mechanic in 1960, which allowed skilled players to earn multiple extra balls for meeting certain objectives. This extended playtime without violating anti-gambling laws. Created by David Gottlieb’s son Alvin Gottlieb, the add-a-ball concept was first implemented in Flipper (1960, D Gottlieb & Company) and was widely adopted by other pinball manufacturers, a prototype of the extra life in digital games.

FIGURE 1.17 Covergirl (1947, Keeney). Note the position of the flippers along the sides of the table that pushed the ball into the center of the game space rather than saving it from rolling out the bottom. United States. (Courtesy of Arcadia, McLean, IL, www.vintagevideogames.com)

These changes were significant enough to help distinguish the differences between gambling machines and pinball machines. The culminating event for pinball occurred on April 2, 1976. Rodger Sharpe, as a respected pinball game designer and skilled player, testified to the New York City Council. His testimony consisted of not only a verbal argument, but also a demonstration of the skill-based elements of the game performed in front of council members in the council chambers. During play, he was able to call his shots with sufficient accuracy and skill that members of the committee immediately took a vote to end the ban following the demonstration. After the decision by New York, other cities followed with the most symbolically important being Chicago, the main city where the American coin-operated industry was centered.

The Sunset of Electromechanical Games

While the removal of pinball bans across the United States was cause for celebration among manufacturers and owners, the nature of game arcades had already changed, as digital coin-op games were flourishing in the late 1970s. Although early digital arcade games lacked the visual detail and the feeling of space found in electromechanical arcade games, they also lacked the maintenance problems caused by complex arrays of moving parts and dirt buildup. Relative to the size of the more elaborate electromechanical pinball and arcade games, coin-op video games were smaller, meaning more machines could occupy a space and collect more coins. Further, electromechanical games were limited by the speed of a rolling ball or the time it took for a solenoid to turn a model missile turret.

The type of games that could be designed digitally presented more dynamic possibilities in gameplay than electromechanical games. Their biggest advantage was the ability to implement a system of progressive difficulty, as it ensured that the game would be constantly attractive to both new and experienced players. In pinball of the 1970s and 1980s, the board always stayed the same and operated at a fixed level of difficulty as they relied solely on the probability of player error increasing with playtime. By the time more dynamic pinball systems were introduced, digital games had become the preference of the majority of game players. Nonetheless, the design knowledge gained in the previous 100 years was invaluable, as it was used to form the basis for arcade games in the early digital era, a topic continued in Chapter 3.

___________

*Herlands, W. B. 1941. Operation of Pinball Machines in the City of New York. New York: Department of Investigation.