Note

Subject: wut the hell tony?

i sent u an email like 4 years ago when i wuz in ur fan club wen u were my favorite skateboarder. well thx alot because I went to your huck jam show and asked you a question and you didnt answer me so i gave up skateboarding because i thought u thought i was a poser. If u get back to me on this i would greatly appreciate it.

Like most pro skaters, I've always been frustrated that skateboarding's mainstream popularity derives primarily from contests, when that's such a small part of what we do. In fact, most pro skaters shun competition entirely and instead build their reps through video parts and skate-mag coverage. That's what makes the sport and the subculture so hard for outsiders to package: At its core, it's about innovation and improvisation. It's about ignoring rules.

As proof, let me make a confession. It isn't exactly a secret, but it seems to be forgotten amid the hype: My most famous competitive feat, when I landed the first-ever 900 during the "best trick" event at the 1999 X Games, shouldn't have counted. I should give ESPN back its medal. Here's why: It took me 12 tries to finally stick a 900 that day, and somewhere around my eighth attempt, time ran out—contest over. I didn't exactly cheat; I just kept climbing back up the ramp after the buzzer sounded, and nobody stopped me.

I wasn't thinking about winning. I only wanted to land a trick that had eluded—and hobbled—me for 10 years, and I knew I was closer than I'd ever been to nailing one. The other guys had stopped skating and were cheering me on, and everybody in the venue knew something was up. So the people running the show (God bless 'em) decided to let me keep going. Despite the crowd and the loudspeakers and the TV cameras, it was in its way a lot like one of those skate sessions that happens every day in schoolyards and skateparks around the world: one kid trying to pull a trick he's never made before, with some friends looking on and giving him high-fives after.

If it had been almost any other sport, security guards would have bum-rushed me to the parking lot. Can you imagine an Olympic high jumper getting the go-ahead to take a few extra tries at a new world record? Or an ice skater being granted a time extension because she's close to nailing a quadruple lutz? If not for skating's anarchist soul, I might still be trying to land my first 9.

Note

From:

Subject: please tell Tony & crew thanks...

I took my 6 year old son to your most recent show. Wow, he loved it. His mom and I went through a very hard divorce a couple of years back and this is the first time we have been able to do something "big" with just the two of us, father and son. I just needed to let Tony and crew know that you did an awesome job.

I retired from contests shortly after that event, but I still loved skating in front of big crowds, and I still got to do it sometimes—but mostly as a sideshow to some bigger event like a concert or a football game. I figured there must be a way for talented action-sports athletes to headline events without competing against one another. So I started asking around. What if we built a portable ramp and practiced routines in advance? Mix in some BMX riders, maybe turn up the juice with a Motocross jump. Invite a good band. Call it something catchy, choreograph a whole show, take it on the road.

The more I talked to people about it, the more I liked it. So I suggested it to Pat. She thought it sounded good, so she started making calls.

We had no idea what we were getting into.

Two years later, when we finally launched the Boom Boom HuckJam tour, we'd concocted one of the most complex and expensive arena-based road shows in history. We needed eight tour buses to ferry the 60-person crew, and 14 semis to schlep the gear, which included a massive portable ramp system. At each stop, we had to hire 100 more local laborers to erect and dismantle the set. It was a juggernaut.

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

Note

To: <[email protected]>

Subject: Grandma Hawk fan

In June, we attended a BBHJ show for my daughter's 10th birthday. My mom, who just turned 58, had the most fun of all! She was up and screaming and jumping around. Tomorrow we are hosting a Tony Hawk birthday party for her.

The idea took root during the 2001 Summer X Games in Philadelphia's First Union Center (now the Wells Fargo Center), which drew a sold-out crowd. I realized that the audience didn't care that much about who won the various events; they'd mainly come to see their favorite skate, BMX, and Motocross heroes perform live. I thought it would be cool to create a tour in which all of my friends could get paid well to travel around the country performing together, like a theater troupe.

By coincidence, a promoter named Steve Moore, from TBA Entertainment, approached me around the same time with the idea of creating just such a show. Steve was enthusiastic and well-meaning, but his company was unwilling to put up any money to get the thing off the ground. That turned out to be a common refrain.

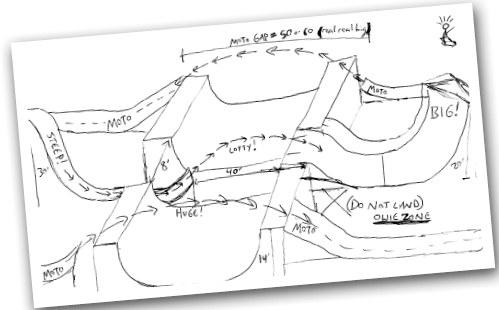

We initially wanted to call the thing "Cirque X." At a lunch meeting I sketched out a rough plan on a napkin for a huge halfpipe encircled by a Motocross track that would allow the Moto guys to jump over the halfpipe while we skated. It also had a separate three-story roll-in that led to a launch ramp, where we'd huck ourselves 40 feet across a gap, land on a downslope, then ride into a vertical quarterpipe, where we'd do one last air 10 to 15 feet above the ramp. We eventually added a full loop, like a Hot Wheels track.

That napkin ended up costing me a million bucks.

Pat and I realized pretty early that we were going to need partners and sponsors to finance all the start-up costs. Steve Moore put us in touch with a large concert promotion company called Concerts West to help book the tour. He also started talking to Toyota about coming on as a partner. Neither of those panned out.

The original napkin sketch of my dream ramp set-up...

In the meantime, my agent at the William Morris Agency, Brian Dubin, told me WMA might be interested in becoming a co-owner and partner of the tour. We had a bunch of meetings with the agency in which we discussed risk, ticket sales, rehearsals, booking procedures, travel logistics, merchandise—all of the minutiae that hadn't occurred to me when I started sketching on that napkin. I quickly came to loathe the WMA bean counter. The guy was really just doing his job, trying to minimize his company's risk, but to me it felt like he took delight in exposing every little cost, and I began to fear he was on a secret mission to scuttle the project. Their bottom-line recommendation: find sponsors to help cover the up-front costs, and find promoters willing to put up guarantees for each date, or just forget the thing and walk away.

... and the finished product come to life. The ramp system and lighting ended up being bigger than most rock′n′roll tour productions and filled the entire floor of huge arenas.

Unfortunately, none of the promoters we talked to had ever tried to sell tickets to such an event, and they refused to put up their own money in advance. Sponsors were equally skeptical.

But I had faith in the idea, so I started writing checks. One of the first and most important payments came in December 2001, when I wired $10,000 to Paul Heuberger, a gifted skate ramp builder from Switzerland, to consult on making a massive, portable halfpipe. He met with Tait Towers, a set-construction company in Pennsylvania. Tait had been in business for years, building extravagant sets for such touring bands as the Rolling Stones, Kiss, U2, and Britney Spears. I gave them a deposit and they got to work.

Although that construction bill would top $1 million, none of our business "partners" were willing to kick in cash to help cover the cost of the ramp. Couldn't blame them, really. We were entering terra incognita. But I felt confident it was worth the risk, so I kept coughing up cash.

The key to the ramp was making it sturdy and portable at the same time. Tait came up with an easy but rock-solid interlocking system that made it possible to erect the entire contraption in four hours and dismantle it in less than three. The thing is now eight years old and has been assembled and disassembled more than 100 times, and it's still, I believe, the best halfpipe in the world.

I'd also been talking all along to a lot of athletes about the possibility of coming out on tour. It helped that I'd promised everyone that for once they'd get paid what they deserved. The initial cast was a dream team:

Skateboarders:

Bob Burnquist

Bucky Lasek

Andy Macdonald

Sergie Ventura

Mat Hoffman

Dave Mirra

Dennis McCoy

John Parker

Simon Tabron

Motocross riders:

Carey Hart

Drake McElroy

Dustin Miller

Clifford Adoptante

Mike Cinqmars

As COO of Tony Hawk Inc., Pat took responsibility for doing the show's financial projections. First, she and our accountants had to figure out how much the whole thing would cost, then calculate what it would take to make a profit: how many shows we'd have to do, how many tickets we'd have to sell, how much we'd have to charge for each ticket, how much sponsorship money we'd have to bring in, and how much branded merchandise we'd have to move.

The logo for our very first Boom Boom HuckJam reflects our humorous take on the Japanese youth culture that influenced the name of the tour.

Meanwhile, in addition to recruiting athletes, I went out to a bunch of old friends to help produce the show. I gravitated to people who lived skating, BMX, and Moto. Because we'd be in huge arenas, we planned to videotape the show in real time and project the action onto JumboTrons, so we needed cameramen who knew how to shoot that stuff. I enlisted Morgan Stone, the creative producer at my video production company, 900 Films; Carl Harris, producer and co-creator of the MTV Sports and Music Festival; and Bruno Musso, a producer who'd worked with us on my Gigantic Skatepark Tour. I also roped in a bunch of people who already worked for me at Tony Hawk Inc.: the multitalented Jared Prindle (our first employee ever, and still an indispensable part of the team) and cinematographer extraordinaire Matt Goodman. These weren't just employees or contractors; they were all old friends who I knew would work their asses off, stay cool, and keep it all fun.

Part of the fun came when we tried to think up a name for the tour. "Cirque X" got scrapped because it was too close to "Cirque du Soleil," so I put the word out to some people I know who are good with words, like Sean Mortimer (one of my oldest friends, and co-author of my autobiography) and my brother Steve. The exercise quickly spun out of control, and we all just started trying to make each other laugh. I've always been a fan of Japanese kitsch and that culture's mangling of the English language. Here are some of the early titles that we considered:

Heavy Air High Boy

Speed Launch Gnarly Man

"Zoom!" Say Gnarly Disaster Boy

Big Air Rocker (No Lame)

At one point the word "HuckJam" popped into my head. So I wrote it down, and then added "Boom Boom" as a prefix, to give it a Japanese flavor. I e-mailed it to the brain trust, and everyone immediately voted for it. In the years since, I've been asked by dozens of reporters where the name came from and what it means. To the first question I say, "No idea." But it actually has meaning: "Boom Boom" refers to the noise (and heavy bass thumps) that comes with loud music and an energized crowd. "Huck" is a term that skaters and snowboarders have used for years; it means to launch into the air: what you do when you launch off a ramp. "Jam," of course, is an ongoing session of creative improvisation.

Once we had the name figured out, everyone got busy. We were aiming at an April 2001 launch date, and still kind of fumbling in the dark, when good fortune struck in the form of a music industry innovator from Laguna Beach.

In early 2001, Pat got a call from out of the blue from a guy named Terry Hardy, who wanted to know if she was interested in joining him and someone named Jim Guerinot in creating a company to manage action-sports athletes. Jim, it turns out, was a major player in the music world. A former vice president at A&M Records, he now owned a music management company called Rebel Waltz. Among his clients at the time were No Doubt, The Offspring, Social Distortion, Beck, and Chris Cornell. (He later went on to add my favorite band, Nine Inch Nails.) Jim was a trailblazer in the business, helping groups like The Offspring get rich by owning their own publishing and negotiating higher royalties. The big news: Jim and his team were also very good at running tours.

The music business was beginning its tailspin at the time, as people were starting to download music online instead of buying CDs. After a few meetings, Jim, Terry, and Pat decided to form a management agency for alt-sports stars like Kelly Slater and Bam Margera. Almost as an afterthought, Jim mentioned that he'd also be happy to help with the Boom Boom HuckJam show. Before we knew it, his people were on the phone booking the tour, and suddenly we had a partner who knew what he was doing, and who was willing to commit resources to the project. Pat called WMA and TBA and politely told them they were off the tour, so to speak.

At Jim's suggestion, we brought in Mike McGinley (aka Goon), a tour accountant for Sting and No Doubt. We also hired one of Jim's best production managers, Ray Woodbury, who'd been a partner on the Warped Tour. I remember that at every meeting we had with the main team, Goon would tell us we were crazy to spend all this money without knowing if anyone would buy a ticket. But we'd heard that before. So we plowed ahead, naïve to the vagaries of the concert business. In the end, Pat, Jim, and I ended up pouring about $2 million into it to get it off the ground, including $500,000 to produce an hour-long "making of the tour" TV show that would air in advance on ESPN, MTV, and various regional networks to promote ticket sales.

Three weeks before the first show, we set up the ramp in an enormous airplane hangar at the former Norton Air Force Base in San Bernardino, east of Los Angeles, where the other athletes and I went to work choreographing the routines. That was a wild, exciting, stressful time. We were trying stuff no one had ever tried before, with up to five people on the ramp at the same time, sometimes riding over and under each other, their trick lists worked out in advance. We made time for a period of improvised riding in the middle of the show—a jam session—but most of it was precisely scripted.

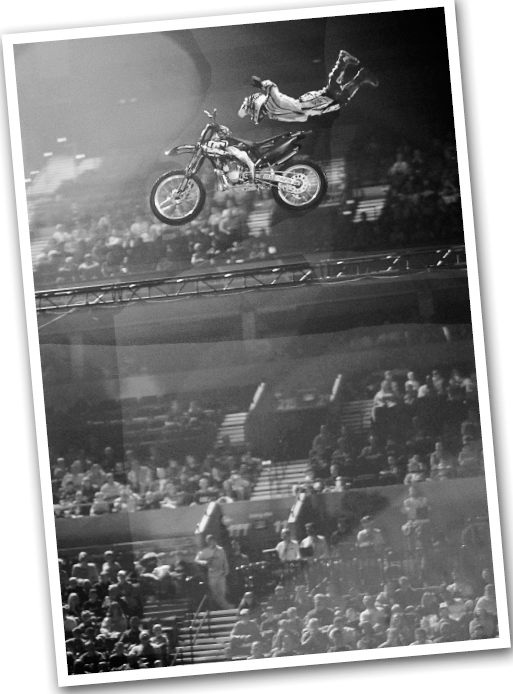

Freestyle Moto-X rider Dustin Miller wows the crowd on our first arena tour.

For the finale, we decided to have the Moto guys fly over the outside edges of the ramp while the rest of us sessioned beneath them. That was the scariest part. We actually had to cordon off sections of the deck with caution tape to keep the skaters and BMXers from wandering into a motorcycle's flight path. As soon as we heard engines, we knew to stay away from certain zones or somebody would get hurt.

The Moto guys were troopers. Clifford Adoptante was fresh off a broken femur and had to use a cane to walk to his bike. The jump was blind, with a 14-foot-high ramp between takeoff and landing blocking their view. On his first attempt, Drake McElroy overshot the landing and broke his jaw. That was just 10 days before opening night, and we ended up replacing him with our Moto coordinator, Micky Dymond, because by the time Drake got jacked, it was too late for anyone else to learn the routines.

As we rehearsed, Jim and Pat inked deals with the various performers' agents, and Jim asked Social D and Offspring to play at the first event. We decided to have the premiere at the Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas.

We started selling tickets eight weeks before the first show. Sales were painfully slow. Two weeks out, we'd sold only 25 percent of the available tickets. We were all worried. Jim, who knew the business as well as anyone, was particularly worried. He told us we had to start making plans to "paper the house," meaning we'd give away tickets to fill empty seats so the press wouldn't declare it a flop. Fortunately, Jim and steadfast promoter Bill Silva did a bang-up job getting local radio stations to promote the show, and we had a surge of last-minute walk-up business. That gave us hope.

Anyway, the show went on, and we all had a blast, and the crowd seemed to enjoy it. USA Today, MTV, Access Hollywood, and ESPN all covered the event, and gave favorable reviews. That night, we popped the champagne, exchanged high-fives, and everybody went home happy. Then Pat, Jim, and I looked at the accountant's reckoning, and freaked. The venue and local labor costs were so enormous, we'd netted next to nothing. At that rate, there was no way we'd recoup all of our start-up costs. It was particularly bittersweet for me. I'd been excited to see so many screaming kids and stoked parents in the stands, but it looked like we were about to lose a whole lot of money.

Our goal had been to launch a summer tour just two months later, but now we were having serious second thoughts. Pat went on a mission to find sponsors. Fortunately, Activision planned to launch the fourth installment of my video game in November of that year. The game's marketing team agreed to be the HuckJam's title sponsor if we'd postpone the tour to coincide with the game's release. Even though kids would be in school by then, we said okay, and began to organize a 24-city tour for the fall, to be sponsored by Activision, Sony PlayStation, and a new pudding-in-tube product called Squeeze-N-Go.

Five months after that first show in Vegas, we gathered up most of the same athletes and crew, studied the films, made some production changes, and went back to the hangar for rehearsals.

After the last rehearsal, when everything was packed, we stepped outside the hangar and took in the sight of the huge convoy of trucks and buses, all ready to roll. I think that may have been the first time the Talking Heads song ran through my head.

In addition to Social D and Offspring, Jim had managed to pull in Face to Face, Good Charlotte, and CKY to play at various stops along the way. Just before the final tour plans were cemented, Jim asked me, "What do you think about Devo?" I thought he was joking. Devo had been one of my favorite bands growing up. They were deeply connected to the underground skate scene of the early 1980s, but I'd never had a chance to see them play because I was so young, and they hadn't toured in years. I thought Jim was crazy, but he said, "I'll call Mark." Meaning Mark Mothersbaugh, the band's co-founder? In my mind, that was the equivalent of saying, "Maybe we should get Zep—I'll call Robert and Jimmie." Devo ended up playing two dates with us, Anaheim and my hometown of San Diego. When they played the SD show, it was my dream demo: friends and family in the crowd and one of my favorite bands playing on the deck. That night, I pulled my first 900 of the tour.

It didn't take long to realize, though, that our plans for the first HuckJam tour were stupidly ambitious: too many big-name bands (with their crews, gear, and personalized sound checks) and too many goofy sideshows each night. During set changes, for instance, we had mimes sweep the ramps with giant brooms, hot models in skin-tight space suits walking around with signs introducing each show segment, and a weird mid-arena lounge area where the athletes were supposed to relax between sessions while being interviewed by emcees.

On top of all that, our ramp system covered the entire arena floor, which meant that at each venue we had to install lights to illuminate about four times more space than the typical rock band. And that, of course, required more workers and more money. The first few dress rehearsals were incredibly dangerous, with airborne motorcycles just missing crew members running to change sets. We ended up using spotters and buying red-yellow-green stoplights to avoid mishaps.

Also, we were so thankful to have sponsors that we made some embarrassing compromises to keep them happy. We initially agreed to give out free Squeeze-N-Go pudding samples during intermission, and to have our emcee, Rick Thorne, lead the audience in a "SQUEEZE AND GO!" chant. That made everybody cringe, including most of the spectators, so I asked Pat to tell the Squeeze-N-Go people that we needed to kill the chant. Before the second tour started, BMX star Dave Mirra went through all of the rehearsals, collected his rehearsal pay, and then, on the day before we were flying out, announced that he was leaving to host a reality show on MTV. That was about as pissed as I've ever been, because he'd kept it a secret and because his replacement wouldn't have time to memorize our routines, which put all of the performers at risk. In another stroke of luck, we persuaded BMX legend Dennis McCoy (who had been cut earlier to make room for a newer rider) to sub for Mirra. Dennis hopped on a plane in Kansas City, studied the routines on video while flying, learned them in one day, and kicked ass the whole tour. He remains a key HuckJam performer to this day.

As the tours progressed, we experimented with more complicated routines that included BMX and skate simultaneously. Andy, Lincoln, K-Rob, and I even attempted a quadruple stack, in which we tried to ride above and below each other on the same side of the ramp at the same instant. Kevin came down on Andy's back and severely rolled his ankle. I ended up carving too far trying to dodge the other three guys and went off the side of the ramp. That was our lone attempt at a four-way.

But there were emotional high points as well. We sometimes arranged with the Make-A-Wish Foundation to arrange VIP seating for severely sick children. At a pre-show meet-and-greet, I promised one of the terminally ill kids I'd do a 900 for him. It took me a few tries, but I made it. On my way back up to the ramp deck, I pointed at him, and his older brother burst into tears. After the show, I went backstage and found a quiet place to cry myself.

By the end of the second tour, we decided to do away with the big-name bands and create our own house band to play covers of our favorite music. That worked out well, and the whole thing started to hum like a well-tuned engine. It wasn't easy, spending seven weeks on the road each year, but the road has its own allure once you get into the rhythm.

In 2004, we spent a long time negotiating a contract with Fox Sports to film a one-off HuckJam show in Phoenix for a 60-minute special to air on Fox's new cable channel, Fuel TV, the first-ever 24/7 action-sports channel. We also cut a deal with Fox to film and create an eight-part reality series, Tony Hawk's HuckJam Diaries. It was mutually beneficial: Fox wanted original programming for their new network, and we needed sponsorship dollars to keep the tour alive. Also, I was (and still am) a fan of Fuel TV.

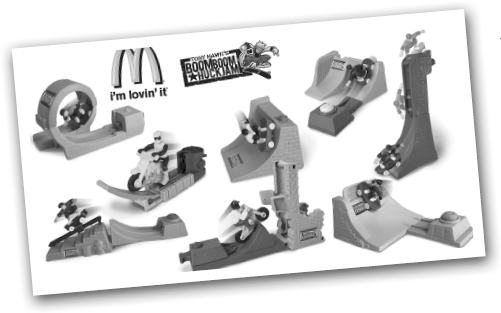

That same year, I was offered a hefty two-year endorsement deal with McDonald's and Powerade. McDonald's wanted to create a Happy Meal with small skate-related toys, and we talked them into using the Boom Boom HuckJam brand. I knew I'd take flak from some core skaters, but I wasn't being duplicitous: My kids were fiends for Happy Meals and McNuggets. McDonald's also agreed to sponsor the 2005 summer tour. They were promoting Powerade as one of their "well" drinks, so Powerade came in as a major sponsor as well. We decided to book another tour, and McDonald's sold 22 million Boom Boom HuckJam Happy Meals that year. And the toys were actually some of the coolest they've ever sold.

McDonald's interpreted the many disciplines of the Boom Boom HuckJam tour into what turned out to be a very popular Happy Meal toy set.

As the tours progressed, it became increasingly clear that our audiences, primarily families, were there to see the action, not see bands, so we ditched the live musicians and created an original pre-recorded soundtrack. Pat's husband, Alan Deremo, an accomplished studio musician, arranged the music and wrote many of the tracks.

The tour kept morphing. In 2006 and 2007, we restricted it to Six Flags amusement parks across the country: eight stops, four shows per stop. The next year we went crazy with a manic 24-city tour that almost killed us all.

Meanwhile, Pat was out pitching the Boom Boom HuckJam to various licensees, which enabled us to extend the brand into markets beyond the core skate world, without placing my name front and center: school supplies, DVDs, bedding, linens, party supplies, room décor, vitamins, flash drives, toys, pool toys, bikes, skateboards, helmets, and safety pads. I'm grateful that those products have kept the show alive and continue to generate income even when we're not actually touring.

But—and I can't say for sure the other athletes agree—I'm jonesing to get back out there. There's nothing like skating in front of an appreciative crowd filled with people of all ages, especially when you can do it without worrying about how you're going to get scored by a bunch of judges.