Chapter 3

A Tour of the New Normal

Given the increasing pace of change, it’s more important than ever to create the right mix of planning and action. And it’s trickier than it has been for earlier generations. It has been kind and generous of others—parents, friends, people we observe or hear about but don’t know, the media—however deliberately or inadvertently—to do some developmental pioneering for us. We’ve learned by observing how they raised their children, did their work and got promoted (or didn’t), treated their friends, planned (or didn’t) in collaboration with their spouses, made (and didn’t) their financial and social decisions, and how they regarded their own aging after age 50. Sometimes we have paid close attention. Other times we’ve ignored them and their experience altogether. What have we learned from our parents, siblings, coworkers, and friends’ successes and mistakes? What have we learned from our own experience? What have we done with that insight as well as insight about ourselves? Cultivating that learning—which applies in the short term but is unlikely to last forever—those insights are an essential part of our lifelong development because they so deeply inform our beliefs, behaviors, imagination, and options, provided we’re paying attention.

I see Fred Mandell of Needham, Massachusetts, as a Renaissance Man. Fred’s mission is to help individuals, leaders, and their teams unlock their full creative powers. As CEO of The Global Institute for the Arts and Leadership (TGIAL), he has mobilized a worldwide network of artists, leaders, entrepreneurs, academics, researchers, and consultants who believe in the power of the arts to lead positive transformational change in our organizations and society. A CEO, an artist, a PhD in history, and an organizational consultant, Fred can be reached through www.artschangeleaders.org.

There is, I can tell you from personal experience, no end to the interesting topics one can discuss with Fred. When I interviewed him, we tried to focus on what’s different now and the accompanying realities.

George: What are we facing today?

Fred: If we look at the world today, it’s very different in dramatic ways from 15 to 20 years ago. And it’s different because the speed of change, the disruptive nature of change, all kinds of things are going on which introduce a very different set of dynamics than existed previously where the world, even if we didn’t realize it at the time, was on a more gradual trajectory. And now we open a newspaper [and], see political change threatening at our doorsteps; we see economic change highly disruptive in terms of 2008. So this is all a boiling stew, and I think it requires a more heightened sense of creative sensibilities for people to be able to make sense of that. Today, not only are we living longer, but we are living longer in a more destabilized context. You and I know that we want to banish the word “retirement” and, if we’re successful in doing that, we’ve introduced a new set of motivations on the part of folks who are aging and want to be engaged. But how does one get engaged in this new context in ways that enable them to make a meaningful contribution rather than creating fear and paralysis?

It’s nice to know we have much in common with others. Still, in the end, it’s called my (or your) life for a reason. We’re similar but also unique. No one else is inside our skin. No one can or should take more responsibility for our lives than we do. That’s what being a grown-up is all about, and it’s very demanding when done well.

WHY CAN’T I JUST LEAP INTO ACTION?

Planning and action are each important. In the right amounts and at the right times, linked together, they will deliver success.

What do we hope to get from planning? First, you get clarity about your direction and intentions. Second, there is decreased (but not eliminated) risk. Third, there is greater confidence from being organized. Fourth, there is the discovery of potentially better alternatives. Fifth, a greater likelihood of success through a combination of achievement and smart adapting as time passes and new information becomes available. This all presumes, of course, that you regularly review and update your plan. If you don’t, a plan can rapidly become the equivalent of an outdated, unconsulted road map stashed in the dashboard’s glove box.

What do we hope to get from action? First, there is immediate gratification that comes from motion and momentum. Second, you get progress and a sense of accomplishment. Third, you get important requested and unrequested feedback and insight. Fourth, there is a decrease in anxiety that waiting—even well informed waiting—can produce. Don’t underestimate our capacity for leaping into action as an anxiety-reduction tool. Consider the attendant cost in time, resources, and energy. Action from habit or for its own sake may not be a great investment. Remember to do a reality check periodically. How well informed is your action? How well informed can it be?

TOO MUCH ACTION, TOO LITTLE PLANNING

Sam and Norma left the freezing temperatures of Cincinnati and fled on holiday to coastal Florida one recent January. Upon arrival, they found the weather to be perfect. They loved walking on the beach in the sunshine holding hands. They enjoyed the restaurants, cultural events, and interesting sites. They found the other snowbirds at adjacent tables to be fun to talk to. They loved being outdoors, golfing, and biking. In short, they fell in love with the place. In one giant, spontaneous leap, they agreed they had found the perfect place to live. No more ice. No more snow. Since both were eligible for early retirement, it seemed simple. They both intended to get part-time jobs after moving. They bought a new house in a Florida retirement community, went back to Cincinnati, did take early retirement, told their kids and grandkids they were moving, sold their house, and made the move. By April they were settled in their new Florida location. It was heaven for about three months.

By the end of May, the newness was beginning to wear off. They found living in a retirement community far less stimulating than they expected, particularly when they discovered that many of the residents were snowbirds and part-time residents. Sam and Norma lived on a street where fewer than half the houses were occupied year-round. The Florida temperatures and humidity began to soar. Interesting part-time jobs were much harder to find than they expected. Volunteer positions were plentiful with the many local nonprofits. They began to miss their grandkids but discovered that—since the kids were getting older now and no longer babies—they and their parents had significant school and sports commitments, which made them unavailable except at holidays and during summer vacation.

Two years later, Sam and Norma sold their Florida house and moved back to Cincinnati. They bought a house down the street from their old one. They also bought a Florida timeshare where they expect to spend the month of January every year. They are in the process of looking for part-time jobs and they are seeing a lot of their grandkids.

TOO MUCH PLANNING, TOO LITTLE ACTION

Beth and Mark wanted an SUV to pull their 20-foot boat. They loved to fish. They loved to be together on the water. They loved to try out different lakes and explore in their boat.

They divided up the duties. Mark would do research on the SUV. Beth would do research on the best loan packages. Their approach was similar: They used spreadsheets to identify the major products (SUVs in Mark’s case and loan programs in Beth’s) down the left column. Across the top, in Mark’s case, were brand, number of doors, amount of horsepower and tow capability, transmission options, cost to insure, price of the trailer license, how much he liked the dealer’s salesperson, and 16 other discrete SUV criteria. Across the top, in Beth’s case, were down payment/equity required, interest rate, number of months and years allowed, monthly payment, how much she liked the bank’s lending officer, and 22 other criteria that she thought were important.

All of the information went into Microsoft Project software on their computer at home for the ease of updating and data massage.

They began the Boat Project in late August. By the time they completed the data gathering and investigation, it was late October. The new year’s models were out. Mark and Beth definitely wanted the newest model. They hadn’t bought that many cars in their life together and both wanted the other to have a brand-new car. So, using the new year’s models, they began the data collection all over again. Then Thanksgiving and Christmas arrived.

The following March, Mark’s employer eliminated many jobs and instituted layoffs. Mark lost his position, but he was fortunate. Within six months, he was back at work. The couple needed to replenish their savings account, and they took four months to do it. Then they went SUV shopping again. Once again the new models were out. Once again they began their data collection.

They think this year will be the year of the new SUV for them. All their friends certainly hope so.

These are two different approaches actually taken by two couples. If we need to create the right amount of planning and the right amount of action, what’s a great model for doing that? While there isn’t a universal, perfect answer to that question because circumstances vary so widely, this is a model that works very well.

The shelf life of education, knowledge, and experience is growing ever shorter. This means adopting the life habit of really smart research and inquiry. The quality of the question drives the quality of the answer.

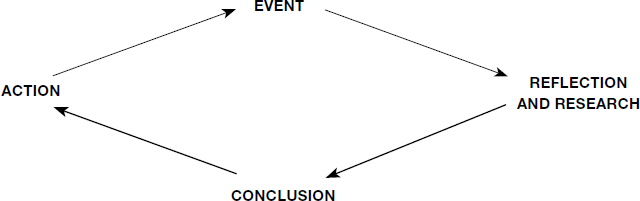

One tool used by professional advisors—psychologists, attorneys, HR professionals—is known as a Learning and Decision Making Loop. (See Figure 3-1.) You begin with an event and work your way around the loop, arriving at a comparable event in the future with a different, more informed viewpoint. These learning loops can be cumulative, in effect stacked upon each other. When imagined this way and seen from the side, the learning loops cumulatively form an upward learning spiral.

Figure 3-1. Learning and Decision Making Loop

MY OWN EXAMPLE

Event: In our late 50s, my wife and I concluded that the large city where we were living was unlikely to be a great place for us to grow older and we would be better off if we made a well-informed leap while we were still young enough to return if our choice turned out to be a disaster. Neither of us had any desire to retire (as in not working at all) . . . and we still haven’t. We had made an agreement that we would try it—whatever it turned out to be—for five years. If it wasn’t a successful experiment, we could return to where we started. We didn’t sell our city condo; we rented it out instead. Whether or not our choice proved sound, we would have the confidence and experience of trying and knowledge about ourselves that would serve us well for the rest of our lives individually and as a couple. It was my job to go out and get the data. I couldn’t come to a conclusion or make any commitments without the full involvement of both of us.

Research: We used a combination of a Template of Needs and On-site Interviews to discover major possibilities for ourselves.

Template of Needs (in random order):

1.A great, warm climate for me and a balm for my lifelong eczema/atopic dermatitis

2.Near the ocean

3.Universities in the area

4.Friendly to small businesses

5.Lots of arts and politics

6.Other people/couples taking risks and trying on new lives

7.A major airport within an hour

8.A house we love or like very much

9.Topography and weather that would make regular outdoor exercise much more likely for both of us than our prior windy and hilly city had been

10.Reasonably affordable

11.Great local health care

On a scale of 1 to 10, we rated each component of the Template of Needs at every location we visited.

We knew that we were unlikely to find a place with a high score in all the categories and agreed we would work with resulting trade-offs as we went along.

Whom did we interview? What did we ask?

You will often hear me say that the quality of the question drives the quality of the answer. I think “When can I retire?” is a bozo question because it is just too simplistic. In fact, in my opinion, one of the greatest After 50 skills is asking more and much smarter questions than we did earlier in our lives.

My wife and I identified the places that were most likely to score high on our template. Before leaping into action, I contacted a variety of friends and asked, “Who do you know who lives in Austin or San Diego or Phoenix or Charleston or any of the other places on our list? Who has moved there recently? Would you open the door for me to talk with them in person when I’m visiting their area?” Everywhere I went I not only saw realtors and talked to the Chamber of Commerce, I also invited a friend of a friend to dinner to ask questions:

1.Now that you’ve been here for a while, how good a choice has it proven to be?

2.How did you choose it to begin with?

3.What has come as a pleasant surprise?

4.What have you had to learn the hard way that you wish you had known in advance?

5.If you had it to do all over again, what would you do? Differently? The same?

6.What has been the easiest part of assimilating here?

7.What has been the most difficult part of assimilating here?

8.What have you discovered about yourself here that you didn’t know before?

9.What is missing that you wish you had? What is in excess here?

10.What am I not asking you about that’s important for me to know?

CONCLUSION

After each trip—the data collection took about two years—my wife and I would return from a trip with information. We would review the information together. In the end, it was coming down to the Phoenix area and we thought we could occasionally visit an ocean. Trade-offs again!

Our live roadways have straightaways. They also have hairpin turns. Less and less is orderly, slow, and linear. Frequently we can’t see around the corner. What you are looking for may come from well outside your intentions and efforts. Be prepared to remain open and aware.

Then my wife and I were sitting in a great big-city tapas restaurant, just the two of us, reviewing the interview data, talking about the template, and comparing notes. The couple at the next table began, unnoticed, to eavesdrop. Finally, they interrupted our conversation, saying, “We’ve been looking, too. Like you, we’ve been here for years. Unlike you, we weren’t organized about our search. We did, however, luck into finding a place that meets all of your template’s requirements. In fact, we just bought a condo there. Would you like the name and number of our realtor? It’s Sarasota, Florida.”

“Florida?” I asked? “We went to the East Coast of Florida and it didn’t much match our template.” “No,” they answered. “You weren’t listening. We said Sarasota. It’s to Florida what Austin is to Texas without the state buildings.”

The couple wrote the realtor’s name and phone number on a cocktail napkin, I put it in my pocket, thanked them for the information. We’ve never seen them since.

Eventually, my wife and I agreed, life had intervened and hit us over the head with one more possibility. We decided we needed to delay our decision one more time. I called my friends again and asked if they knew anyone in the Sarasota area. My friend Walt in Tahoe said his former competitor in the (I kid you not) coffin business in Ohio, Dennis, had retired there. Walt opened the door for me to visit Sarasota, meet Dennis, and ask all my questions.

It turned out that for us Sarasota had the highest score on our template of all the options we researched. We didn’t want to be snowbirds. We didn’t want endless leisure. We wanted to make the commitment of buying a house and living there full-time for five years. Would our experiment succeed? Would we gain the confidence and conscious awareness/competence that should result from living our way into the choice and risk?

Here we are nine years later. It wasn’t always easy. It was often surprisingly challenging and rewarding. Our experiment has been a success. We aren’t quite the same people as we were before. We have the security of knowing that no matter what happens through the rest of our lives, individually and as a couple, we have the ability individually and together to adapt, learn, enjoy, and prosper. That’s no small ROI from the risk we took. Is this a good choice for everyone? No. But it surely worked for us. And your own large or small version of your own over-50 adventure could work for you.

We went around the learning loop countless times. An event would be imposed on us or we would seek an experience (an event), ask good questions (research), come to some sort of interim conclusion that would inform our action until the next time around the loop, which was usually sooner rather than later and informed our experience, research, and conclusion yet again.

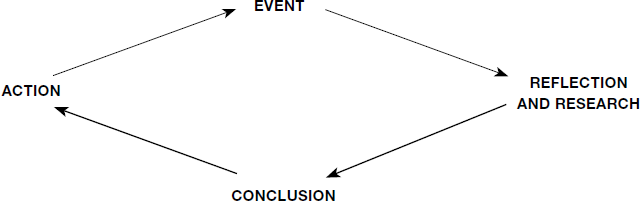

ONE MORE LOOK AT THE LEARNING LOOP FROM A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE

Scale is very important. Are we seeing only single events or trips around the loop? Are we seeing several loops accrued over time, which form patterns? Are we seeing ourselves? Are we seeing impact on the loops of the larger systems in which we operate? Are we confusing—and overreacting to—single events, interpreting them as if they were patterns? Do we have the ability to know how far from something to stand to really see it? Or how close? Using scale effectively is an important After 50 skill. Therefore, it’s important to see the learning loop as a single experience and as a series of experiences, connected and stacked upon each other, that establish one or more patterns that we can work with in our own learning. See Figure 3-2 below.

Figure 3-2.

One time around the Learning Loop is a smart thing to do. Cumulative, deliberate learning is even smarter.

Living your After 50 life with this model as a way of life can create the kinds of awareness, information gathering, informed conclusions and decisions, and smart actions that will be necessary After 50, as circumstances and we ourselves change with and without warning and with or without our permission. It sets up a continuous feedback loop, allowing you to make informed decisions and adjustments as you go along. Of course, this will call into question what is “normal” when life is lived based on change and a series of small and large course corrections as opposed to hanging onto one image or construct of “normal” for a long time.

A LOOK AT NEW NORMAL VS. OLD NORMAL

What role does “normal” play for many of us? We think of it as a rule or standard of behavior shared by members of our social group. We can trust it. It won’t sneak up on us or make us look foolish. Norms may be internalized; they can be incorporated within the individual so that there is conformity without external rewards or punishments, or they may be enforced by positive or negative sanctions from without. The social unit sharing particular norms may be small (e.g., a clique of friends) or may include all adult members of a society. Norms are more specific than values or ideals: Honesty is a general value, but the cluster of rules and behaviors defining what constitutes honest behavior in a particular situation are norms.

Norms are usually paradoxical in nature. They are a kind of anchor to keep us from drifting too far. They can also serve to keep us anchored in place when we should be moving on:

1.They keep us safely and securely in place and comfortable regardless of what is happening around us. They also prevent us from moving and changing too quickly but also help us do so when it’s necessary.

2.They keep us moving along; we can’t stop and examine everything or we’d never get anything done. Also, they often serve as a substitute for the work of thinking and questioning at important times because it’s much easier to stay in Old Normal than it is to do the demanding, reflective work of reassessing its current validity.

3.They give us a strong decision-making framework and they regularly blind us through the illusion that there are no grays and only two alternatives, yes or no, black or white.

We naturally look for opposites to help us make sense of everything in between. And, again paradoxically, working only with opposites dramatically limits possibilities because everything in between is missed or dismissed. We use opposites as a basis for communication, too. It’s how our bodies and brains are built. Opposites are comforting and don’t require us to work hard at thinking, understanding, and deciding. Not one of these opposites would exist without the other. Black and white. Left and right. Up and down. Hot and cold. Light and dark. Dry and wet. Sharp and dull. Summer and winter. Back and forth. Try imagining morning without evening. They are both required.

This works so well for us, we use opposites to work with much more abstract concepts: Right and wrong. Young and old. Conservative and liberal. Progress and regress. Happy and unhappy. Normal and abnormal. Where we get into trouble is when we fail to acknowledge that there is any position or content between them that could possibly be equally valid or of value.

The truth about normal is that it is continually evolving. We also confuse normal with healthy (vs. unhealthy), moral (vs. immoral), or trustworthy (vs. untrustworthy). Every time we load these other dimensions onto normal, we charge the conversation and decrease the likelihood of successful communication. We may want to see normal as a fixed point—old or new—but that’s more about our comfort, and sometimes intellectual laziness, than it is about truth. Some of what used to be normal is still normal: aging, working, procreation, enthusiasm, and disappointment,

New Normal is a term in business and economics that began with the financial conditions following the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the aftermath of the 2008–2012 global recession. The term has since been applied in a variety of contexts including social science. It suggests that what was previously abnormal has to be reexamined in the current context and often admitted into the normal category. There is no doubt that what was considered abnormal before may have since become commonplace. Living much longer. Much-reduced desire to retire. Gay marriage. Congressional polarization. Genetically altered foods. One truth about the new, technologically driven New Normal is that it will be both fast paced and include more than simple opposites.

The New Normal won’t necessarily be a smooth extension of our past, adjusted for age and updated intentions. Intentions are expectations that are too distant or unformed to work well as a goal. If you have any doubts about this, go back to Chapter 2 and reread The Retirement Story of Bobbie. Yours probably won’t be identical but it may have some of the same aspects.

Under the New Normal, each generation has the opportunity to learn from each of the others—from people both older and younger than they are. No single generation can know it all.

Dan Schawbel, himself a Millennial, is a New York Times bestselling author, serial entrepreneur, Fortune 500 consultant, Millennial TV personality, global keynote speaker, career and workplace expert, personal branding coach, and start-up advisor. His mission in life is to support his Millennial generation from student to CEO. I had the opportunity to interview Dan about the importance of goals and what shouldn’t be a goal. You can learn more about Dan and his work at http://danschawbel.com.

George: How far out are your goals, Dan?

Dan: So here is what I do. I have five main business goals and five personal goals. For each goal I have a checklist with sub-goals and due dates. Some are pretty constant. Some are a little volatile. I’ve blown my goals away last year and this year. But I think I need at least 10 goals from a platform-building and financial standpoint to be relevant. But I’ve realized there are certain things I won’t identify as a goal. I have a production company that’s shopping around for a reality TV show. That was a goal last year but it’s so unpredictable that it’s not a goal for this year even though it’s still in motion. I’ve learned what I can be accountable for and what is so out of my control that I can’t really have a goal around it. I think you called those intentions earlier in our conversation, George.

Old Normal is a term developed from our increasing use of and embrace of the term New Normal. We needed an opposite to feel comfortable. There’s the opposite theme again.

My colleague Richard Eisenberg is the managing editor and senior editor of the Money & Security and Work & Purpose channels at www.nextavenue.org (PBS Site for People 50 And Older). He has been a personal finance editor and writer at Money, Yahoo, Good Housekeeping, and CBS MoneyWatch. Rich can be reached through http://www.nextavenue.org/writer/richard-eisenberg.

When I interviewed Rich, we talked about aspects of what will compel us to change.

George: So what’s going to be compelling to people in your opinion to begin to pay attention? Because our brains look for patterns and the familiar, a lot of these things are going to be unfamiliar unless we get the word out there. What’s going to be compelling for people?

Rich: I think that what’s going to be compelling is they know that the predictable life that they’ve led for the first, let’s say, two or three decades of their working lives is ending or it has already ended. They know that it’s going to be up to them to figure out how to deal with that, and if they don’t, they realize that they could be depressed, they could be having serious financial problems, or they could be having serious relationship problems. So I think what’s compelling them is they realize that basically they have no alternative but to figure it out on their own because they can’t expect that things will just, you know, row along merrily the way they might have in the past. The pressure is on them.

George: And is that partly because our institutions—whether an employee pension system or the larger churches—will be unable to take care of us the way we used to expect?

Rich: I think it has a lot to do with the fact that the institutions have changed on us and we weren’t necessarily prepared for that. Some of that change is from the employers and some of that, as you say, are really the changes in the accelerating load facing community organizations. Also, I think it has to do with families today and the fact that more of us are in a position where we need to do caregiving duties for our parents or our wives or husbands or relatives, brothers and sisters, in a way that maybe wasn’t necessarily the case in the past, probably because fewer were living longer lives as they are today. Also, change has probably happened because the governments aren’t providing for these kinds of things. So I think people will realize they have to come up with some ways to plan for these caregiving duties both in terms of geography—the ability to be there when the parent needs them—and being able to assume financial responsibility. And I think similarly the flip side is in many cases people in their 50s and 60s have adult children now and have very good relationships with their adult children. In the past, families tended to mostly stay in the same area all throughout their lives. These days, in many cases, the adult children have moved away because that’s where their jobs are or because of a better fit for the life that they wanted to lead. This is not because they want to be away from their parents but because that’s just where life is taking them. Now the 50-and-older parents are often finding that they want to come up with a solution to get closer one way or the other. This is and will be a compelling need.

It is important for people to see and think beyond the limits of the current “normal” because, unless we are careful, we tend to construct Old Normal as natural and good and construct New Normal as deviant and terrible. Do we do this because we are clinging to the familiar? Do we do this because we haven’t paid enough attention to our evolution to see where the change is coming from? Try wading into the middle of the Colorado River at its silent but most powerful point above the dams. Hold your right hand out and try to stop the river. Then complain about the result. It seems to me we have to work with the river, not regret that we couldn’t stop it. The same goes for the evolution of normal that is happening every day in large and small ways. Old Normal keeps changing. New Normal keeps evolving. The pace accelerates. Real/current normal is what exists today. After 50 we won’t be able to remain fixed points either and still be relevant.

What’s a better way, then, to frame and understand what we are facing After 50 than Old and New Normal?

The answer is: growing our understanding and sophistication about change.

My colleague Kerry Hannon is a nationally recognized expert on career transitions, personal finance, and retirement. She is a frequent TV and radio commentator and is a sought-after keynote speaker at conferences across the country. She has spent more than two decades covering all aspects of careers, business, and personal finance as a columnist, editor, and writer for the nation’s leading media companies, including the New York Times, Forbes, Money, U.S. News & World Report, and USA Today. (Find Kerry at www.kerryhannon.com.)

Part of our interview for the book focused on the impact of all of this change on women.

George: I’m looking at the numbers on late-in-life divorce and that’s one of the fastest-growing rates of divorce. What does this mean for women?

Kerry: As you have probably heard, gray divorce is pretty common these days. And women who find themselves facing a split in their 50s and beyond need to cast a steely eye and get tough. This is not a time to fall apart and get strung out on emotional energy. It’s business. Marriage, after all, at the core, is a business partnership.

One of the biggest mistakes women make is trying to cling to some symbol of security and stability amidst all the chaos. Emotionally, they want to hang on to the house in a divorce settlement. Rarely should you choose the house over retirement assets. The best scenario is to sell the house and split the proceeds.

Here’s why: The retirement savings amassed by your spouse may be substantial and likely to grow in the future. But a home is probably going to cost you money to maintain and its future value is less predictable.

I advise women to negotiate hard for a portion of an ex’s retirement assets, too, over alimony, if possible, because alimony is taxable and that’s just a short-term plan. And if you are age 62 or older, were married for more than 10 years and have not remarried, you can claim on his Social Security. Collecting this benefit will not impact what your ex-spouse receives. Many women don’t grasp these financial moves. It can help to have a certified financial planner at your side to help clear your head and get down to the brass financial tacks.

But, George, let’s step back and look at the basic issues women face and why divorce trips them up financially in a far more painful way than it does their ex. Women are more likely to step away from their career paths by taking time off to raise children or care for aging parents. Men, on average, are in the workforce nine years longer than women, according to the Social Security Administration data.

Women also tend to work for smaller firms and nonprofits that either don’t offer retirement savings plans or don’t match employees’ contributions to their retirement savings plans.

Then, too, yep, there’s that nagging pay gap. Even professional women are earning 72 cents on the dollar to their male counterpart, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Finally, women also live on average five years longer than men. The truth is that most American women will find themselves single at some point from the age of 65 to the end of life. That means they don’t have someone to share the cost of daily living expenses or to help with retirement savings.

Little wonder that study after study shows that after losing a partner due to death or divorce, a woman’s standard of living generally drops. Barring large sums in life insurance or other assets, the economics of widowhood usually include a sharp drop in income, according to a report by the Women’s Institute for a Secure Retirement, a nonprofit based in Washington, D.C. For many women, the road to poverty begins after their husbands die. As women age, they become more vulnerable to poverty. Nearly a third of single women over age 75 are living in poverty with less than $890 a month to live on.

This means women should be prepared to navigate the financial world on their own in their golden years.

George: So what are some meaningful life options?

Kerry: OK. That’s the harsh reality for many women. But it’s not all a desperate scenario of gloom and doom. Women are plainly increasing their share of both income and wealth in many sectors of our society. Many women today are in a stronger financial position than in previous generations. Increasingly, women are significant breadwinners.

Boomer women have worked and earned more than any previous generation, increasing their retirement savings as they go. Boomer women are earning their own Social Security benefits and will receive bigger Social Security checks, adjusted for inflation, than women in the past. Moreover, more of us will have our own pensions and retirement accounts than our mother’s generation.

Women are starting their own businesses. They have savings and are, in many instances, better investors than their male counterparts. They have characteristics, in my opinion, that help them tally up better investment returns than men because they’re not in it to outperform the market. They’re in it for their long-term goals, so it is slow and steady with thoughtful decisions based on doing their research, and they’re less likely to jump ship and sell if the market takes a dip. Studies from Vanguard and Fidelity also back me up on this better investor reality.

And many Boomer women can look forward to two or more inheritances. One may come from their husbands, who’ll likely predecease them; women live roughly four years longer than men, on average. Another bequest could be the gift of parents or in-laws. Money or assets might even be passed along by siblings.

By some estimates, as much as two-thirds of all wealth in the U.S. will be controlled by women by the year 2030. And women tend to be philanthropists. They give back.

Change can be slow and inexorable, the way glaciers sliding to the sea used to be or how a sunflower grows from a seed to a mature plant. Change can also be fast and permanent like Krakatoa exploding or the moment Neil Armstrong first set foot on the Moon.

You can’t think of change as being homogenous. The change model I prefer is the distinction between Continuous Change and Discontinuous Change. They aren’t just opposites. There is usually a continuum of possibilities between them. Why is this especially important for people After 50? Because these types of changes—and the continuum between them—are different from our habit of only paying attention to the Continuous Change to which we are accustomed. Enter frequent but not regular Discontinuous Change. If you cannot see the difference, you will make the mistake of approaching them in identical ways and using identical tools. This, as you will see, can get people After 50 nowhere and cost both time and resources for no progress.

First I will talk about the two types of change from my perspective. Then we’ll listen in on an interview I conducted with Steve Carnevale. He brings a strong business perspective to understanding change. He also brings a strong family perspective. Like a lot of us, he is living in both arenas as well as the After 50 arena simultaneously.

Continuous Change

Continuous Change isn’t new. If you are about age 50, the kind of change with which you are most likely to be familiar is Continuous Change. Think cars. Standard transmission to automatic. Crank windows to push button. Think whitewall tires with tubes to all-weather tires without. Think education. Graduating from the fourth to the fifth to the sixth grades. Think work and career in a stable company and profession, moving gradually but continually up the ladder toward eventual retirement. Think dating to wedding to children and/or house to PTA and the kids’ sports to empty nesters to retirement and golden years. Think wood stoves to electric to microwaves to convection; think brooms to upright and canister vacuums to built-in vacuum systems to robotic vacuums. At the time they were discontinuous because something stopped—cooking on a wood stove for instance. In hindsight we can see the longer, continuous trend continuing. You get the point. Gradual, continuous change and improvement. It was clearly visible most of the time. Although it may have been advertised as revolutionary to earn your business, it wasn’t really. And we don’t always like it. In my current car you have to slide your finger across a bar to increase or decrease sound volume. I’d much rather have the old knobs back because I didn’t have to take my eyes of traffic to use them as I do with the finger-sliding technology.

Discontinuous Change

Discontinuous Change isn’t new either, but is increasingly a greater and greater percentage of the change we are facing. The advent of cell phones that were also cameras, texting devices, app machines, and financial information accessors led directly to the rapid decline of cell phones that were only phones, home/landline telephones, and branch banking. For the traditional telephone companies and the banks, this was definitely discontinuous change in how they did business, the jobs they needed to fill, the expectations of their customers, and the way we think of communication and banking. If you are older than age 50, you have likely experienced Discontinuous Change in the form of a divorce or a major illness or a sudden, large inheritance, although you may not have known the term or distinguished it from Continuous Change in making your plans and life decisions.

I think the distinction between Continuous and Discontinuous Change, plus being aware of the continuum between the two and all of those possibilities, is another key After 50 awareness we need to cultivate.

In fact, I think it’s so important that I’m going to bring in another expert here before I go on with my own explanations. What follows is an interview with my colleague Steve Carnevale. He’s a University of Michigan grad and the father of 18-year-old twin sons. He is an investor and a veteran of Silicon Valley and has served on many not-for-profit boards. We have been friends and colleagues for so long that no matter who is asking the questions, it becomes a lengthy and lively discourse. (For more about Steve, see www.PointCypressVentures.com.)

George: Let’s begin by talking about what Discontinuous and Continuous Change means.

Steve: OK. So I think my general notion of it is that Continuous Change is incremental and Discontinuous Change is not incremental; it is a dramatic shift in thinking about something.

George: Give me an example of Continuous Change in the workplace and one in our personal lives.

Steve: Let’s talk about it in the workplace. In the workplace, Continuous Change is what I would call the normal world where people are pretty comfortable with whatever environment they’re in and they’re trying to make it a little bit better and looking for pushing the edges of progress, in whatever that means. In Discontinuous Change, you’re thinking about breaking your entire business model and pursuing a whole different strategy typically because you’re in crisis, and so it’s a much more radical thought. The business model is in many ways the equivalent of an individual’s set of plans, habits, and expectations to lead a successful life.

George: Then let’s take it down to the individual worker level.

Steve: I think the individual worker level in general is cast with execution and they’re not pursuing Discontinuous Change. It isn’t part of their daily lives at home or at work, generally, which can put them at a disadvantage when they get to retirement and their own, extended later lives. The worker and their jobs are usually aligned with productivity and Continuous Change. The Discontinuous Change that I have experienced is always created or recognized at an executive level where you have to dramatically change the way the business does things.

I think the human condition is by definition one of Continuous Change, and very few people set themselves up to easily look at or willingly think about Discontinuous Change because it’s painful to reexamine everything—what is done, how it’s done, whether or not it makes sense anymore, and what, if anything, should be done instead.

I was thinking the other day about the fact that, when we have children, it’s hard to comprehend that this little child is going to be big someday. I was looking at my sons just yesterday. It feels very natural now but I remember looking at them and not imagining them grown up when they were still 10. Now that they are tall, I realize that these processes happen slowly, incrementally enough that they’re easy to digest.

So the process of life itself is one that evolves relatively slowly and relatively incrementally—Continuous Change—unless there is something that occurs that changes. That could be an earthquake, it could be that you’re suddenly out of a job and now you have to move. It could be that your wife decides to divorce. We seldom invest in the future in such a way that it would prepare us for Discontinuous Change even if we see it coming and realize that we’re going to need to prepare ourselves. We aren’t attuned to the difference between the two kinds of change and I think we’re going to need to be as the pace of change all around us increases and what we used to take for granted may no longer be reliable.

George: That’s actually very interesting because I find myself now wondering if it’s just that we are so good at adapting to Continuous Change that we neither discern the difference nor change our actions until we’re really forced into a crisis mode. And even then we will want to stick to our tried-and-true ways.

Steve: I think we live in blissful denial in most aspects of our personal life and we also know that some of us as human beings are pretty good at Continuous Change and some people aren’t very good at it.

George: How about businesses?

Steve: So let’s go to the corporate level. How do businesses work with continuing Discontinuous Change? Well, again my experience has been that companies are just like people, only maybe worse. There’s a momentum that goes on and the complexity of working with everybody; even if you know you need to change it is very hard because now it isn’t just one person making the decision to change. You have to come up with a collective decision to change and even if you’re the CEO it’s very hard to harness that collective recognition that you need to change proactively as opposed to reactively, and so in a company situation we often don’t change in a major way unless we’re faced with a crisis. And this same thing can also happen in families where one person recognizes the need for change and has a difficult time getting other family members on board and thinking/acting in a different way.

George: Let’s talk about After 50. It seems to me that the issue isn’t just acceleration and quantity of change. It’s also that we have more Discontinuous Change. For instance, as much as retirement has been held as a gold standard, an increasing portion of the population is not going to be able to afford to or want to live that dream. They will live longer, have to work longer, and will need to be engaged and do things they think are worthwhile. This means Discontinuous Change for employers, employees, coworkers, ways of making money, career designs, health care, housing, product and service design, and transportation, just to name a few.

Steve: Well, before I answer that, I think you’ve raised an interesting question, which is even if you can afford to not face Discontinuous Change because you can temporarily buy your way out of it, there becomes an interesting question of whether that is really the right answer or not. Having plenty of money allows you to not change at all, but that doesn’t mean that that’s the right thing to do for you or your family.

George: Or the healthy thing to do.

Steve: Exactly. Because you might continue to propagate behaviors that are either bad for you or don’t optimize the life that could be good for you. You don’t change because you don’t have to and that’s part of the problem of not having a crisis when the change might actually create a better life for you. I think that that’s a whole interesting dynamic in getting people to do it consciously and proactively rather than reactively, and therefore maybe not at all if they have enough money to react.

George: My wife and I decided to take the chance and move across the country to where we knew no one while we were still young enough to go back if we wanted to. We determined that if we could successfully build a life from scratch in our late 50s, nothing could happen to us in the future for which we didn’t have the adaptive mind-set and skills.

Steve: So it seems like there are multiple things here. One is the recognition that Discontinuous Change is something that you need to actively think about and you’re likely going to need to respond to. If you really want to maximize your life, and you have got a long life left After 50, you have to put yourself in the mind-set of challenging yourself on an ongoing basis.

George: So what are the biggest factors in resilience, then, from your standpoint?

Steve: I think some of them are believing that you can change. I think some of them are envisioning, having the skill set to being able to envision an alternate future. And I think that, just like in many other circumstances, we’re better at doing that for other people than for ourselves. It is hard to see ourselves differently. And so you need enlightened external friends or change professionals who can be change agents, some external reference that helps you see that you have the capacity to do things that you didn’t know existed or didn’t know you had or could learn.

George: What am I not asking you about regarding Continuous and Discontinuous Change that I need to be asking you about?

Steve: Yes. Why do we care?

George: I care because as people approach 50 or leave 50 behind, most of us are pretty good at Continues Change—my car is wearing out; I can go and buy a new car; my kids are leaving; I am going to grieve but I am going to invest in them and help them move on.

As a grandparent I think it’s my job to give my grandchildren discontinuous experiences. Sometimes with me and sometimes just arranged by me. They usually involve well-supervised opportunities, people they don’t know, an opportunity to learn something brand new that stretches their sense of themselves. I try to arrange activities that are all within the safety of me knowing what will happen, dropping them off in the morning and picking them up in the afternoon, things like circus school, scuba diving, or theater camp.

My oldest granddaughter, almost 17, lived with my wife and me for a part of the summer doing an internship. It was her first experience of work, being responsible to people she doesn’t know, living away from her immediate family, having her own wheels, and living—not visiting—on the other side of the country from her parents’ home. This was intentional Discontinuous Change for her in full cooperation with her parents.

Steve: I care because I can see the difference in my future and my sons’ future as a result of a combination of Continuous and Discontinuous Change. If we cannot always see in advance and be prepared, and by definition we cannot, then what are the skills, disciplines, and awarenesses we all must have to live high-quality lives in the future?

How about those of us over 50? Would we be wise to hand-pick and participate in Discontinuous Change experiences that would benefit us by increasing our adaptability and awareness? You bet we would. Can touring a foreign country, seeing it from the inside of a bus, surrounded by people like us, be an enlightening experience? Yes. But is it likely to be deeply discontinuous? It depends upon how separate we are from the experience. If we only get off the bus to see local dancers perform and then we get back on the bus, we’re clearly quite separate from the experience. If we get off the bus and spend three to four weeks working in a local village school teaching English and live with a local family while doing so, we are having an immersion experience. Likely it will be a discontinuous one that surprises us by challenging our assumptions and giving us the gift of growing awareness and greater adaptability.

I am not suggesting that all of us over 50 should go live and work in a foreign village. I am suggesting, however, that 1) finding, 2) choosing, and 3) benefiting from discontinuous experiences is an individual responsibility that can be done near home and far away, too.

It seems to me that over 50 is exactly the time to make sure we are skilled at working with Continuous Change and Discontinuous Change because it is going to happen. Why wait until a Discontinuous Change—loss of spouse, illness, household move far away by people we are accustomed to depending on, termination of jobs and industry that we have taken for granted, winning the lottery and suddenly having to be a wise investor and consumer at a whole different level—has roared through our lives and left us in the situation of simultaneously developing the skills we need and solving/resolving what we are now facing?

EMILE AND FRANCINE

Emile and Francine, in their early 70s, came to me for personal consulting. Nothing was wrong. They were retired with enough money. They got along beautifully and were, in fact, the envy of their friends for their harmony together. In my book they were especially smart. Knowing they had no problem to solve didn’t deter them. They knew something was going to come along that would be discontinuous in nature. “How could I help them?” they wanted to know. As we talked, we all realized they wanted support in 1) finding, 2) choosing, and 3) benefiting from early learning about something they would face in the future. When I asked them what they most feared, they both said being alone without the other one. As we explored the kinds of learning available to them, we realized that “being alone” wasn’t the real issue at all. Being satisfied as an individual was the issue. It had been decades since they felt like individuals.

During all these years they had been “joined at the hip.” To treat this as a problem and solve it would, in my opinion, have dishonored what they had been so proud of all these years. What non-problem-and-solution approach did we take? We decided they each wanted to face the discontinuous likelihood that they would survive the other one. Therefore, learning, not problem and solution, was the desired experience. We had found what they wanted. As for choosing, they took my recommendation that they take one day a week off from each other (they chose Thursdays) and actively explore and experience being an individual with their own interests and activities. We didn’t dishonor their relationship. We added another dimension to their lives: greater independence and individuality. One got active in volunteering on Thursdays. The other went to work for a business start-up on Thursdays. They reported that their Thursday evening dinner conversations were increasingly lively. And they were happy for each other. They had had the courage to experiment with a kind of learning that would give them the experience to deal with the Discontinuous Change of loss when the time came. They didn’t expect it to be perfect, but whoever survived the other wouldn’t have to begin to cope from scratch.

Like my granddaughter, Emile and Francine had a future that would involve both Continuous and Discontinuous Change. Being older wouldn’t spare them that. Also like my granddaughter, they took the leap and benefited greatly from doing it wisely.

Before we finish, let’s pursue some more specific information about change and how it can affect retirement planning, life planning, and our living our futures generally. I think most of us get Continuous Change. Here is a way to think about Disruptive Change.

Think about the new ways of driving: We are facing the advent of cars that drive themselves from auto manufacturers new to the marketplace. The impact on jobs that required drivers and vehicles could be enormous and very disruptive.

Think education. College graduation is no longer a guarantee either of short- or long-term employment. The shelf life of usable knowledge is much shorter. Lifelong learning and skills updating will be assumed. The concept of a four-year degree as a bundled, discrete step into maturity and a learning experience and then you are done is unravelling rapidly. Colleges are going to have to be competitive in new ways that will change their models. Universities and colleges are already increasingly being assessed in terms of graduates’ employability and employment including compensation. Since most colleges and universities weren’t designed to perform on this metric, an earthquake of change is happening. That’s disruptive.

Think politics. We used to have two parties that were reasonably distinct from each other. There was campaigning and we knew that trusting our election process and institutions was a fundamental part of perpetuating democracy. Candidates disagreed but generally treated each other respectfully in public. Where are we now? Think back to the recent presidential campaign and election!

Think the use of all possible learning resources all the time. My friend Dick Bolles, 90, the internationally known author of the bestselling career book What Color Is Your Parachute 2017, told me in an interview how important paying attention and learning is to him at every age. “What I know about me is that anytime I see anything—I watch TV most nights with my wife and each night we watch a Western or a mystery or a foreign film—I’ll see something in the pictures we’re watching that makes me curious. So I never watch TV without my iPhone right at hand. The minute I get curious about something, I go straight to Wikipedia on my phone to find out more about it. If I see something about a historical period, I’ll look it up to see if it’s accurate or not. If I see an old-time actor or actress, I wonder what ever happened to him or her and I’ll look to see what really did happen. So the thing that characterizes my life is endless curiosity. I’m not just sitting there watching movies. I am sitting there constantly learning.”

Think work. Jobs and companies are no longer remotely permanent. Skills and expertise must be updated on a regular basis. Lifelong employment for all intents and purposes doesn’t exist. Freelancing may possibly be as important to earning a living as jobs are. Work for pay may decreasingly be configured as a job. Robotics, software, and other technologies are replacing middle management and other bulwarks of the middle class. Disruptive.

Think marriage. Divorce is common and socially acceptable. In 1990, only one in 10 divorces involved people ages 50 and older. Now it’s one in four. The over-50 divorce rate is even higher among those who remarried. The institution of marriage and its purposes are fundamentally changing for people After 50.

Think retirement planning. Think life planning. Think planning period. Interim, iterative, adjustable planning with a much shorter planning horizon is the emerging norm. Successful planning is now shorter term and success looks like the plan, and we ourselves adapt as required. Gone are the days when long-term retirement and life plan success is measured by flawless execution of a permanent plan.

Think about the distinction between retirement planning and life planning. It has almost entirely disappeared.

PUTTING CHANGE IN PERSPECTIVE WITH OUR NEW UNDERSTANDING

We’ve looked at change in detail, especially continuous and discontinuous. It’s very important that you understand these concepts AND you pay attention to the continuum between them.

Many changes can be experienced as a hybrid of the two, measured in the amount of stability or discontinuity that’s caused as a result of the change overall. A forest fire that destroys everything in its path for a month will be discontinuous to the homeowners who lost their houses with no notice as it swept across the countryside. Seen (perspective again) from the historic perspective over the centuries, that fire may be considered an example of Continuous Change.

Also, what’s Continuous Change to you may be discontinuous to someone else. The company that employed you for years was recently sold, and massive layoffs are happening across the board. You were going to retire anyway in a few months, so you’ve accelerated your retirement date. The woman at the desk next to yours is 40 years old and a single mother with three kids. She didn’t see this coming and hasn’t done any job search since she was hired seven years ago. For her this will probably be highly Discontinuous Change.

It is crucial that people After 50 be able to manage their planning with their eyes on both continuous and discontinuous . . . and on everything in between. We often don’t see Continuous Change because it isn’t dramatic. We often don’t see Discontinuous Change because it is so system-altering that it’s upon us before we realize how this systemic change is going to affect important aspects of our lives and plans. Nevertheless, successful planning and successful adaptation requires a willingness to see and a skill adapting to both kinds of change and the continuum between them.

What is important for all of us to realize, as we plan and execute and adapt and then plan and act and adapt some more in incremental stages, is that Discontinuous Change in our lives must be managed differently from Continuous Change. Continuous Change often requires an updating of the plan accordingly. Discontinuous Change usually requires major revision of the plan and how it is executed. Or it drives the need for a new plan altogether. Failing to distinguish between the two can put you behind the Eight Ball rapidly. Unfortunately, it’s hard to catch up later if you weren’t paying attention as you went along.

In my opinion, many vestiges of the Old Normal are still with us and will continue to be. The process of Continuous Change is so gradual that we won’t notice. In many ways we prefer it because we can usually see it coming, somehow frame it as a problem to be solved or an opportunity to be resolved, come up with a solution, and move on to what’s next. Working well with Discontinuous Change is a lot more work than that.

Also in my opinion, many vestiges of the Old Normal will continue to be blown away by Discontinuous Change that we don’t see coming and therefore can’t prepare for. It’s going to be crucial for many of us After 50 to develop the capacity to see what’s really going on around us and make important distinctions to be able to handle it well.

Reader Exercise

When was the last time you drove home or rode the subway and remembered everything you saw? When was the last time you arrived at home with no recollection of the streets or traffic lights or faces in the crowd? If we paid attention to everything all the time, we’d never have time for anything else. On the other hand, many of us have developed the ability to go through our daily lives without the need to think about things from tying our shoes to the route home. This means we’re running the risk of not really seeing some important aspects of our lives. The following questions are intended to get us to take a closer look with conscious perspective. They are also intended to get us to name important information—current circumstances and future expectations—because unless we name it, we can’t work with it now or going forward. And you will need to do that in order to gain the maximum return from this book.

1.What does normal look like in your life at your current age?

2.What kinds of Continuous Change are happening in your life now?

3.What kinds of Discontinuous Change are happening in your life now?

4.What kinds of change are possible in your life over the next 25 years?

5.Which changes will be chosen by you and which will happen without your permission?

The most common form of retirement and life planning usually says: Find your bliss/purpose and pursue it with gusto. The underlying logic for this path is:

1.You only have one bliss or purpose and you just haven’t found it yet. That is a significant failure or omission on your part so far.

2.This “bliss” is waiting there for you with open arms. All you have to do is name it and make it your life’s purpose. With enough passion, everything else will pretty much fall into place.

3.Like the American Work Dream (“Just work hard and you will get there, kid, even if you have to pull yourself up by your bootstraps”), there isn’t much room in this approach for what it will take, if there will be any demand for it, or if others have gotten there before you and will be appalled at the notion of sharing.

4.It’s a pretty linear and solitary thing: Figure it out, go after it, and get there. There isn’t much provision here for anything morphing, being discontinuously changed, or simply disappearing along the way.

5.There is absolutely no provision for the possibility that the experience will change you along the way and you might then want to choose and pursue an alternative or aligned bliss or purpose.

I am perfectly willing to subscribe to the notion that you have life purposes that you brought with you or created.

I am equally willing to subscribe to the notion that bliss or joy is connected to and even a by-product of you exploring your purposes. No one wants to do something he/she doesn’t like at all, much less for the rest of his/her life.

What I am NOT willing to subscribe to is the seductive, even tantalizing, notion that great retirement and life planning begins by imagining your future and working backward to your present based on imagining your bliss. It’s all too easy to fall in romantic love with the future you imagine and never do an adequate job of assessing where you are. It’s essential that we do the more difficult but ultimately far more productive and grounded work of assessing where we are before we leap into our imaginations and sally forth into our futures.

There is another very strong reason to work from the present forward to the future. Take a close look After 50 at who our heroes used to be: cowboys, visionary but often solitary pioneers, soldiers, courageous individuals who struggled against great odds as workers for social change like civil rights and union representation, fictional/unique characters like Superman and Batwoman, men and women who have crossed known boundaries to travel into and walk in space, inventors who built (digital or not) products that changed our lives from airplanes to software, great but tragic figures who gave their lives for us and our country like John F. Kennedy and Sharon Christa McAuliffe and Judith A. Resnik and Martin Luther King, and men and women of enduring accomplishment who we could hold up as worthy models indefinitely.

What do many of these people have in common?

1.They had a dream they pursued, often alone until they built a network of engaged others.

2.They set out to right wrongs or create something new we had not previously imagined.

3.They seized the initiative and often could control the mini-environment in which they were working as long as disaster didn’t happen.

4.They lived in a time when (for good or bad) significant social/professional class tiers or hierarchy and academic/professional/financial qualifications were important for credibility and to get attention.

5.They lived in a time when societies were comparatively low tech: telephones, television, and newspapers. Innovations were, for the most part, extensions of current technologies (i.e., Maxwell Smart’s shoe phone and the Batmobile).

What’s different now and what does it mean for retirement and life planning?

1.The body of information is vast and growing exponentially. No matter how smart or educated we are, no one can know it all (or even close) anymore. Information is assaulting us 24-7.

2.We need to make instant decisions about where to invest our attention and energy. We can’t absorb it all as we become increasingly saturated.

3.We are no longer in a fixed or slow-moving, manufacturing-oriented economy. Instead we’re in a fast-paced, rapidly changing, highly networked service economy that depends upon new and evolving technologies to proceed, maneuver, and hold it all together.

4.Our futures and—like it or not—the quality of our lives is growing increasingly dependent upon our active memberships in a range of networks to have access to the information, the right kinds of relationships, and to increase the likelihood of getting the outcomes we want. We’re going to become more, not less, interdependent with people we know well and those we don’t. We’re going to have to understand how to operate well under those circumstances or risk losing out and being marginalized at best. This goes directly to the heart of successful life and retirement planning.

Many of us (including myself) After 50 complain from time to time that our grandchildren like to text us at most four- to six-word messages and can pay far more attention to their tablet devices than they do to us.

If you are 55 or 65 or 75 and have a strong desire for financial capacity, meaningful engagement, belonging, and stimulation, how likely is it that you can accomplish them without ramping ourselves up to participate along with the rest of the world in leveraging the networks and technologies on which life is increasingly running? I argue that it is unlikely or even impossible for us to limit ourselves to dated approaches and preferences, no matter how comfortable they are, if we expect to get and accomplish what we want in the years and decades remaining in our lives.

This has a huge impact on what smart retirement and life planning looks like and how we must go about it.

What we now know with certainty:

•There are a lot of us facing this need for retirement and life planning. We aren’t alone. We also aren’t identical. One shape of life or retirement planning or execution won’t fit everyone by a long shot.

•There is a revolution happening in the shape of retirement. We’re going to have to craft our own best-fit version for ourselves.

•There is a revolution happening in both retirement planning and life planning. We’re going to have to be much better at incremental, shorter-term planning and be ready to adapt both the plan and ourselves as necessary. The plan will have to be a living, breathing part of us rather than something we put on paper and store in a drawer.

•Regardless of our previous background and experience, we’re going to have to think and act more like the strategic and tactical CEO of our lives rather than as an employee expecting the larger strategies to be handed to us for tactical execution.

RECAP OF WHAT WE’VE COVERED SO FAR

Let’s go a step further and have a short recap of where we’ve been in this book so far. This is essential to avoid falling into the trap of thinking, “Oh! That was interesting,” and then leaping directly back into our accustomed, less-informed ways of thinking, planning, and acting.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau and AARP, we are a population of 108.7 million people age 50 plus. Of this total, 53.5 million are women and 55.2 million are men.

We are often lumped under labels like Baby Boomer and Traditionalist—based on birth year—as if we were vastly more alike than we are different.

Retirement used to be universally understood as a discrete life stage when you didn’t work anymore and were entering into golden years of leisure.

Retirement now—although we may leave our full-time, recent employment—doesn’t necessarily suggest not working. All it means is that we’re facing a large menu of possibilities, some of which we’ll have to create and some of which will be presented to us. The fact that we still use the word retirement, as outdated as it is, won’t change until there is a newer and more accurate descriptor that comes along. Until then we’re stuck with retirement.

The truth is that, while we have many similarities and needs in common, in practice there could be almost as many forms of “retirement” in practice as there are numbers of us. One shape will not fit all.

Our After 50 lives are going to be different from our parents’ and grandparents’ because the world is different and so are we. Having survived the Great Depression and WWII, they, understandably, craved lives of stability with clear rules, roles, and as little Discontinuous Change as possible. How realistic is that for us today in today’s world?

The real work before us After 50 is to stop thinking of retirement as a stage of life and begin to understand that what we are really doing is planning for multiple, overlapping components of our lives. For some people, work will be a part of it for a long time, if not indefinitely. For some of us—with the financial capacity—it will mean leaving work behind.

To succeed at planning, executing, plan revision, adapting, and executing some more, holding multiple perspectives will be crucial. We will also need to identify, comprehend, and alter—as necessary—the major life models we have used to think, make decisions, and act. This will, of course, require challenging our own assumptions periodically.

We will need to be able to understand, identify, and work with all the forms of change that will come into our futures. This will require paying attention. For some of us this could be uncomfortable. For many of us it could be awkward at first just as every new kind of work is in the beginning.

The After 50 years aren’t just another set of decades. They contain two huge gifts—gifts that we’ll have to accept and nurture to realize their potential.

1.We can continue to grow, change, and evolve, individually and collectively.

2.We can understand and take advantage of the years After 50 as years that are valuable and exciting in their own right AND that serve as the runway for the quality of life in our later years. A great 12-year-old doesn’t start at age 11. A great 91-year-old doesn’t start at age 90.

However old you are now, your future deserves a well-informed plan adaptable you. It’s never too late to begin. It’s never too late to update.

This leads to what you need to explore in crafting your retirement and your life plan. What are essential questions you need to ask and answers you need to find for your short-term, medium-range, and long-term future?