10

ALLYSHIP IS A JOURNEY

The path of allyship is different for each of us. It can be uncomfortable—and it’s our job as allies to get comfortable with discomfort. It can make us confront our fears, question long-held beliefs, and rethink our worldview—and it’s our job to choose vulnerability and courage, as we grow to become more empathetic humans. It can also open new worlds and new understanding, help us build new relationships, lead better, love better, and live in alignment with our values. Allyship is a lifelong journey of learning, showing empathy, and taking action.

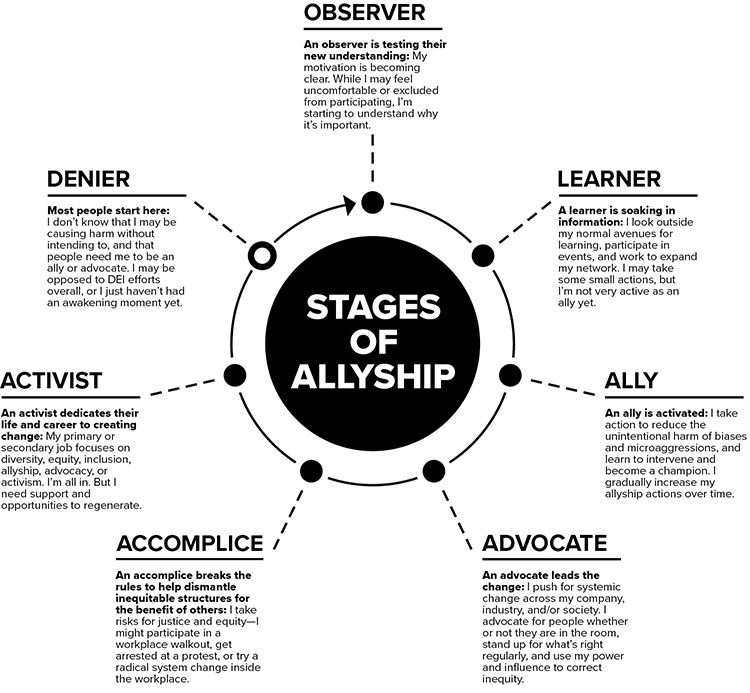

Through primary and secondary research, and my work with clients to build allyship in leaders and across organizations, I’ve found that the allyship journey lies on a continuum of change—or Stages of Allyship. As shown in Figure 10.1, allies tend to evolve on similar paths. We might begin with denial. I certainly did! But once we have a breakthrough, an aha moment, we begin to observe and test our assumptions. We then take the step of learning and may go through some deep and difficult unlearning and personal investigation. The learning never stops, but at some point we start to take action as an ally. We might remain here, or become an advocate, working to change systems from within them, leading the change from our position of power. And/or we might work to change the system by breaking the rules, protesting, or changing laws as an accomplice. A few of us continue on to become activists, actively working to create major shifts in institutional inequity and injustice. These are all part of the allyship journey:

FIGURE 10.1 How Allies Evolve

Denier. A denier might be here because they haven’t yet recognized inequity. They may be causing harm without intending to, remaining complicit in the status quo. If you were here once, even recently, know that most people start here and what you do from here can make a big difference. You picked up this book, you’re moving forward, and hopefully you’re beginning to take action. That’s what is most important now! A small percentage of people are here because they don’t believe or don’t want to believe in unfairness, inequity, and injustice (our research found this to be about 3 percent of the population).1 Most people are eventually open to change and can have that moment of awakening that moves us from denier to observer.

Observer. When someone is in the observer stage, they are testing this new understanding, checking to see if it’s real. Their motivation for allyship is becoming clear, but observers are not yet participating and may feel uncomfortable or excluded from participation. They are starting to understand the importance of this work and are weighing the pros and cons of taking steps to change. Developing empathy, understanding the benefits of DEI and allyship, and seeing examples of allyship will help observers become learners.

Learner. A learner is soaking in the information, and looking outside normal avenues for learning. They may be reading, asking questions, taking courses, participating in events, and expanding their network. They may take a few small actions, but they are not active allies yet. Learners may be going through feelings of guilt and shame, and may find excuses for not taking action as they work to unlearn and relearn. Learners become allies by building empathy and understanding, tapping into additional motivations (like improved leadership skills and collective team benefits) and learning tangible, actionable steps they can take to be an ally.

It’s important to move from observing and learning to action. Allies can’t stay in the safe space of nonaction; we must take uncomfortable steps forward to become active allies.

Ally. An ally takes action. They work to reduce the unintentional harm of biases and microaggressions, and may begin to intervene and become a champion. They stand up or step back as needed for people with underrepresented identities to have opportunities, gradually increasing their actions over time. Allies grow through training and coaching, continuing to build empathy, working in a culture that values allyship action, and having access to tools and processes that help them step into advocacy roles. Help allies learn from mistakes, educate them with empathy, and support them to continue taking action.

Advocate. An advocate leads the change, pushing for systemic change across company, industry, and/or society. They are a champion, advocating for someone whether or not they are in the room, and dedicating their power and influence to create systemic change. To help continue to grow their advocacy, advocates can benefit from additional resources, programs, tools, and training. Invite them to be members or sponsors of employee resource groups; provide mentor, sponsor, and volunteer opportunities; and give them inclusive leadership and change management training. When teams work together as advocates, recognize their collective accomplishments, and tell their story as an example for other teams.

My work with companies generally centers around these first five stages. Yet it is important to recognize the additional work of allyship can go beyond these—we also need accomplices and activists in our work to create systemic change.

Accomplice. An accomplice is an advocate who breaks the rules or the law to dismantle inequitable structures. Sometimes they are called co-conspirators or abettors. Accomplices cause major disruptions through protests, strikes, walkouts, major policy changes, legal challenges, and breaking the law to shine light on an unjust law or system. Depending on your role, power, and influence, this may be something you can do in the workplace as well as outside the workplace. Generally it does take some personal or professional risk to be an accomplice.

Activist. An activist dedicates their life and career to create change. They might significantly pivot their career and take a substantial pay cut to improve diversity, equity, inclusion, allyship, and/or advocacy. Often activists are the teachers of allies and advocates, the leaders of movements, the ones who work long hours to build coalitions, redesign systems, and lead organizations through long-term DEI change management. Activists need trust and respect, support, resources, and training to learn change management and behavior change strategies.

Often activists are people with underrepresented identities who experience microaggressions and inequity along with toxicity that can come from the work itself—they need breaks to regenerate and outlets to process toxicity and trauma that can come from doing the work long-term. If this is you: someone told me once to step out when you need to—your colleagues will fill in while you regenerate—and then come back in when you’re ready.

We’re all a work in progress—allyship unfolds throughout our lives as we receive new information, meet new people, and put ourselves in new and often uncomfortable situations. We might move back and forth along this continuum during our careers and find ourselves at different stages depending on which group we are an ally for. For example, someone might be an activist for women, but a learner when it comes to allyship for Black, Indigenous, and disabled people.

At any given time, I can be a learner, ally, accomplice, advocate, and activist—depending on which group I’m working to be an ally for, and what work I’m doing in my work at that moment. I’m still learning and unlearning, still catching my own biases frequently, and continuing to uncover deep-seated biases I didn’t realize I had.

How Should I Feel as an Ally?

During one of our Tech Inclusion Conferences in 2020, I received a message from someone attending the event. He said he was learning a lot about the change that needs to be made and the actions he can take. But as a White man who is not marginalized or excluded in his life and work, he wanted to know how he should feel. He said he was feeling shame that some people experienced racism, sexism, and ableism and he did not—and wondered if he should be feeling shame or guilt or like a “bad guy.” Here is what I told him:

You are not alone in feeling this. I can’t tell you how to feel, but I can tell you how I feel in case it’s helpful. I feel this too—as a White person, there is a lot of privilege that I have that is unfair. I have feelings of guilt, and also feel a responsibility to use my privilege to correct this.

I also know I need to listen and learn how to ensure I do no additional harm, and apologize if/when I do. And learn what people really need from me as an ally. This is not easy stuff. As I continue down my own journey as an ally, I continue to learn at deeper levels where inequities are. It is hard to unsee once you see them.

And shame is real. Many, many people feel shame as they learn more—I’ve been doing this work for many years and would say that most people feel shame and/or guilt at one point or another. I would recommend not ignoring the guilt and shame because that can be unhealthy. Go to the heart of it and ask yourself why you’re feeling it. When you do that, you become a better ally, and it’s easier to help other people (potential allies) through the process.

That you are here, present and learning is a great thing. Thank you for asking me this.

Everyone’s allyship journey is unique. When you’re observing and learning, allyship can feel overwhelming. You may experience guilt, shame, or fear—but choose courage to investigate your feelings, move through them, and take action. When you’re in the ally stage, intervening can be challenging and uncomfortable—but get comfortable with discomfort, have a growth mindset, and know that you’ll get better at it, what’s difficult now will get easier.

And when you do something as an advocate, wow—it’s incredible to see the impact. Your colleagues thrive in their work and careers, your team is more innovative, and you and your colleagues are happier and healthier. Celebrate your colleagues’ successes, reflect on your own accomplishments, and take pride in your team’s growth.

I’m a Person with an Underrepresented Identity. Why Do I Need to Be an Ally When I’m Already Overburdened?

My friend and colleague Vanessa Roanhorse taught me to think about allyship as “reciprocity of love and respect”—she and I are mutual allies.3 With a relationship of mutual allyship, we show up for each other when we’re needed. I can be an ally for her by using my platform to amplify her voice, work, and culture; I can share my network and check in with her when I know times are rough (like when I found out the Diné people in the Navajo Nation were severely impacted by COVID-19 and the resulting economic crisis). She can be an ally for me by sharing her networks with me and educating me in how to be a better ally for Indigenous people. Our mutual allyship deepens our relationship, and it helps us both grow.

The reality is, we all need each other—there is a lot of work to do. We have to help one another rise and then send the ladder back down and help other people rise. It’s easier for us to recognize microaggressions because we experience them too, and if we’re mutually intervening for each other, we’ll go further together. So take a break when you need to, but then come back and let’s work together.

Healing from Our Own Trauma

Sometimes the best thing we can do as people with marginalized identities is to do our own healing. I spoke of my friend Michael Thomas in “Step 1: Learn, Unlearn, Relearn.” In addition to being an attorney, Michael is a certified instructor in raja yoga from the Niroga Institute in Oakland, California. As part of his certification, he worked with incarcerated men in restorative justice circles, where they discussed the harm they have caused, as well as the harm they have experienced themselves. What he learned is that if you disengage from your own past harm and don’t work to heal from it, you risk causing harm to other people.4

This is deep, important inner work. Because as we learned, unresolved trauma can be harmful to ourselves and each other. Trauma can be passed from generation to generation through fetal cells, as well as culture and family norms. It can also affect how we treat our colleagues, friends, and neighbors. Many of us have experienced intergenerational or personal trauma. And each of us can break the cycle.

When we don’t resolve our trauma, we can also internalize trauma, internalize racism, sexism, ableism, and other forms of discrimination—and begin to believe it ourselves. In her TED talk in 2019, America Ferrera talked about how as a Latina actress, she needed to change her beliefs and values about herself to affect change:

For both Michael and I, yoga and meditation have been incredibly powerful tools for healing and growth. Individual or group therapy, executive coaching, journaling, and gathering with other people who have experienced similar trauma can also help.

I suspect when you picked up this book you didn’t think you’d be asked to investigate so deeply, but it’s important: do you have unresolved trauma? If you do, I encourage you to work to heal from it—for yourself first and foremost, as well as your colleagues, your family, your neighbors, and people around the world who all need you.

What Do I Do When I Mess Up?

You’re going to mess up, we all do. The first step is to be open to the experience of making mistakes. Often, we immediately become defensive, but that doesn’t help anyone. Be open to feedback as an ally. Invite feedback. Listen to feedback with empathy and work to understand the impact.

Then communicate your understanding and genuinely apologize. Don’t expect someone to forgive you immediately, give them time. Let them know how you will correct yourself moving forward. It may be a situation where there were significant consequences for the other person—if for example, you didn’t invite them to an important meeting, or said something in front of colleagues that impacted their reputation or ability to fully participate. In that case, tell the person how you might repair the situation, and ask them for feedback about what they think would work best. Come to a conclusion together.

Commit to taking action so that it doesn’t happen again. You may have to work to rebuild any lost trust. The best way to do that is to follow through with treating the impact, demonstrate change (don’t let it happen again), and continue to become a stronger advocate.

Be transparent and authentic about what you’ve learned—with yourself, the person you harmed, and publicly if you’re comfortable sharing your learning process. Don’t share the name or details of the other person without their permission of course, but you can share your journey of allyship so that other people learn from your mistakes, and learn how to repair them.

The more that allyship becomes a norm in your culture, the easier this will become. Work to develop a culture where people give and receive feedback, recognize and address microaggressions, and learn to become better allies together.

What Is Canceling (or Public Shaming) and Should I Do It?

Cancel culture is a public backlash, boycott, withdrawal of support, ostracization, or embarrassment after someone does or says something offensive, abusive, ignorant, racist, sexist, ableist, heterosexist, anti-Muslim, anti-Semitic, anti-trans, and so on. Canceling can significantly impact the reputations of individuals, brands, and companies and can damage careers and families. In some cases it can also encourage sympathy for the offenders.

While the term is relatively new (many say it originated in the 1991 film New Jack City, but didn’t become popular until over a decade later via Black Twitter), it is similar to “call-out culture” and other public shaming that has been around since the Civil Rights Movement.7 Does it work? Former US President Barack Obama answered this way: “There is this sense that ‘the way of me making change is to be as judgmental as possible about other people and that’s enough.’ . . . That’s not activism. That’s not bringing about change. If all you’re doing is casting stones, you’re probably not going to get that far. That’s easy to do.”8

If your goal is to change someone’s behavior, public shaming is not generally an effective tool. Feelings of failure, shame, or guilt can make someone step out of their commitment to allyship. They are less likely to be vulnerable and have the courage to take risks. So it’s important not to publicly shame anyone who is moving along the stages of allyship, but instead to meet them where they are, provide constructive, empathetic feedback, and offer them the tools they need when they need them.

Almost every time we host a conference or large event at Change Catalyst, someone “shames” our team publicly (usually on Twitter) for not being inclusive enough in some way: we don’t have Indigenous speakers (we had seven that year), we don’t have accessibility (we host one of the most accessible tech conferences), we aren’t involving the local community (we work intimately with the local community), we’re White feminists (for years, we’ve been deeply active in broadening diversity, equity, and inclusion for people of all underrepresented groups)—each time these public tweets have been wrong, often revealing a bias of the tweet’s author. What do these tweets do? They cause controversy, reduce our ticket sales, center around the person tweeting rather than the work we do to create change, and make our team exhausted and deflated—because it takes a lot of work to put on an inclusive conference, and to be shamed for doing the opposite is hard. I love that people want change to happen, but this is just not an effective approach.

At around the same time our conference is happening, usually several major tech conferences are held that are much less diverse and inclusive, and no one says a word to them. Rather than publicly shaming the people who are working to create change because we don’t think they are doing it right, let’s spend our time focused on making deeper, more powerful change, together.

If your goal is behavior change, lead with empathy and assume good intent until you know otherwise. Seek to educate and support someone in their growth as an ally. Consider calling people in first, instead of calling them out. If you don’t believe there are Indigenous speakers, for example, ask someone if they have Indigenous speakers joining them. If they say no, you might tell them why it’s important and suggest some possible speakers, or push them toward organizations where they might find Indigenous speakers.

I am often called in, regularly receiving feedback from people who have been incredibly helpful. It’s how I learned the difference between people-first language and identity-first language (thank you, Andrea Vu Chasko), that it’s important to have live CART captioning for Deaf and Hard of Hearing people who don’t use Sign Language (thank you, Svetlana Kouznetsova), that we need prayer rooms near single-stall or gendered restrooms with a sink where people can wash before prayer (thank you, Antonia Ford), and much more.

My rule of thumb is this: if a person or an organization has good intent but they’ve made a mistake, I seek to call them in, ask questions, and then educate (not shame) them. If I don’t get a response the first time, I try again. If I still don’t hear back, sometimes I’ll let it alone because they aren’t ready—they are not even at the learning stage of allyship. There are so many people and organizations that do want to change but don’t know how, that I prefer to focus on helping them. You make the call here, though—if they are still creating harm, you may want to say something publicly to hold them accountable.

Public accountability is not the same thing as shaming. What I have learned over the years is that when companies are held publicly accountable—through press, regulation, policies, customer feedback, and peer pressure—things change more rapidly, suddenly budgets are allocated, and DEI work is prioritized from the top. This looks like asking questions, holding them to their public statements (e.g., if they’ve made a public statement about Black Lives Matter or #MeToo) or publicly stated diversity goals, convening stakeholders and requesting commitments, and creating policies and regulations to keep them in check and hold companies accountable.

How Do I Convince People Allyship (or DEI) Is Important?

I get this question all the time in my trainings, keynotes, and podcast: “What do I say to convince someone who can’t be convinced?” I’d like to say, “Just hand them this book and send them on their way!” But there is some work to do first to get them to the learner stage.

First, decide where you want to spend your energy. Early on in my DEI work, I realized I was expending a lot of energy on the people who are actively opposed to diversity, equity, and inclusion. It was depleting me to the point where I didn’t have the energy to do my training and advocacy work. Then I realized: there are so many more people who do care, but just don’t know what to do as an ally. They are ready to be activated, and just need to be equipped with information, tools, and actions. So I made a decision to focus on the people who are observers, learners, allies, and advocates—and sometimes accomplices and activists—to help them create change. Where will you focus your energy? It’s all important.

Wherever people are on the allyship journey, if you want to help them move forward, you must meet them where they are. People in denial have not had their awareness moment yet. We often want to throw information at people to make them understand, but that isn’t usually how behavior change works. Everyone has their own entry point into allyship; find out what theirs might be.

Think back to a time when you were in denial: what made you aware? It’s often a life-changing experience, like having a child and realizing you want them to live in an equitable world, seeing a Black person murdered on camera or watching the world rise up against systemic injustice, hearing a traumatic experience a colleague or a friend went through, or experiencing trauma yourself. Or perhaps it was at a training or event, or a story you read in the news.11

You can’t re-create this awareness moment for someone—except perhaps by sharing deeply your own experience or working with a group of people to share your experiences together. You might start with an open, safe dialogue. Listen with empathy. Find out their feelings, learn what they are resisting. Share your own feelings and experiences. Remember, change takes time; you probably won’t convince anyone in one conversation, though it’s possible. I encourage, you not to become too attached to the outcome for a specific person because often it takes years for people to emerge from denial.

Once people have an awareness moment, they become an observer. They are checking to see if inequity is a real thing and if being an ally is someone they want to become. They’re sort of trying it on for size in the dressing room—so you can be there in the store bringing them items to try on, but they are the only ones who can decide what they will walk out the door wearing. Be a role model, and help them learn ways that allyship can benefit them. Once they’re ready to learn, give them some basics—stories, data, historical context—and yes, now you can give them this book!

Not everyone will become an ally. Sometimes you just can’t get them there, and you need to check in with yourself from time to time to be sure you’re spending time and energy in places that matter and are good for your well-being. And do take care of yourself—having conversations with people early in their journey can be emotionally challenging.

What If My Company Isn’t Focused on DEI, or My Leadership Doesn’t Care—How Can I Create Change?

This can be frustrating and difficult if you’re from an underrepresented group, I’m sending lots of good energy your way. If your company and leadership aren’t focused on DEI, you can do a lot of work as an ally on your own: doing no harm, advocating, standing up for what’s right, and even leading the change in your individual work and in your industry.

If there is no DEI work being done at your company, advocate for it. You might form a committee or coalition to discuss ways that you can create and advocate for change. Perhaps put together the business case for leadership: share statistics about the importance of DEI to business, any internal data you have around turnover and lack of diversity, and any DEI work being done in your industry by competitors. They also might need to better visualize what DEI work means—ask leadership if your committee can put together a rough idea of some things you might start to work on first. Make sure that list is short and has some quick wins where you can point to success!

If you’re hitting too many roadblocks or not feeling welcome or safe, you may consider if this company is the right one for you. Only you can know that. Do you want to spend your energy where it’s not possible to create change, or do you want to work for a company where you can make a real difference? If you’re not in a healthy work environment, consider making a careful plan to find new opportunities.

What Can I Do If I’m Not in a Leadership Position?

You can lead the change no matter what position you’re in! Start by learning and doing no harm, of course, and then model allyship for your colleagues and help them learn along their allyship journey. Mentor and send the ladder back down to those who are earlier in their career. Advocate for change in your company, and even help create that change if you have the time. Volunteer and find other ways to help create change in your industry. Work on your inclusive leadership skills to be ready when you are a leader. If you’re leading any projects—or even meetings—you can put these skills into practice. And share your experience as an ally on social media, blogs, and internal company channels.

Why Do Some People Not Want Me to Intervene?

Wayne and I were in Puerto Rico several years ago giving a DEI training to CEOs of medium-sized businesses. In the room were 29 White Latinos, one White Latina, me, and Wayne, who is Black. They were all generally receptive to the work we were doing, except one person in the room: the woman. She denied that this was an important issue, vehemently saying that DEI wasn’t important and that people should earn their spot based on merit.

This is common in my work, that the one person in the room from an underrepresented identity does not want to talk about diversity. I see this surface on social media as well. People have worked so hard to get where they are as the “only,” carefully navigating spaces where they didn’t fully belong, adapting and assimilating language and mannerisms, covering and masking if they needed to along the way. It’s survival. They might not want to be called out as different, made part of the out-group, have people focus on them when talking about DEI, open themselves up to stereotypes and other biases, or feel stereotype threat and tokenism. They might just want to do their job and be part of the team. They also may be exhausted or done fighting.

Another way this shows up is people saying they are OK with harassment or jokes made about their identity or even telling jokes themselves. Or when you try a microintervention tactic after a microaggression, but the person experiencing the microaggression blows it off or gets angry at you for pointing it out.

The best thing you can do for them as an ally is to get more people like them in the room so they don’t bear the full weight of representation and responsibility. When you’re working to intervene or advocate on their behalf, respect their wishes and avoid calling attention to them. Intervene privately or in ways that are less overt—for instance, redirecting a conversation away from a microaggression or opening up a conversation to make sure they have room to speak.

Sometimes people don’t want other people to intervene because they don’t trust the person to intervene in a way that would help the situation. Build that trust, talk with the person about what might work best for them. And regardless, check in with them when they’ve experienced a microaggression—always work to treat the impact.

How Is Allyship Different in the Remote Workplace?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I received this question a lot. And as companies continue to grow their remote workforce and workplaces become more dispersed across regions and countries, this is an important question. Almost everything in this book applies to the remote workplace as well as the physical workplace. When you’re conversing via chats, video, and other internal software, there are a few more things to keep in mind:

Tone doesn’t come through the chat. Sometimes I can tell something is not sitting right with one of my team members, and I ask what’s wrong. They might tell me “I’m sorry I disappointed you.” Disappointment was nowhere on my mind; I was just working to achieve a solution to a problem! Sometimes you have to describe context, check in with each other, and remind each other that tone doesn’t come through the chat, and not to assume tone. This can be especially important when working with people from different regions of the world.

People will say things via chat that they wouldn’t say in person. In many of the companies I work with, the worst microaggressions happen in backroom chats. Have a code of conduct that everyone knows about, where you can easily reference it and point to violations. If you’re in a large company, there should be a person or team dedicated to ensuring safety and inclusion on internal platforms. Use microinterventions. Know where and how to report people if violations continue, and who to contact immediately if multiple people are violating the code of conduct.

If you witness a microaggression in a video or phone call, still use microinterventions. This works pretty much the same way it does in person, though you may choose to educate someone privately more often in the remote workplace.

In video, your body language and facial expressions are heightened. Consequently, because it’s all you can see, it’s really important to mind microaggressions and consider microaffirmations in your body language and expressions. I often keep my video window open to watch myself, so I can quickly catch if I’m unintentionally conveying the wrong message with my face. I might be curious what is in someone’s video background, but they perceive that I’m confused at what they are saying. Also if you’ve had a difficult meeting, give yourself a moment to reset before entering a new meeting, so you’re bringing the energy you want to bring.

Be inclusive and accessible in videoconferencing. Talk through agendas and visuals for anyone who is Blind, Low Vision, or on the phone. If people drop out and then return, welcome them back and catch them up briefly. Be inclusive in scheduling meetings as well. Sometimes companies with headquarters in one area of the world will use that time zone as the normal. This is a little act of exclusion for people outside that time zone. Consider mixing it up, and holding meetings that are centered on other time zones too. Also keep in mind parenting/caregiver schedules.

Overcommunicate and provide clarity. This is something our team has to consistently remind ourselves to do. Communicate what you’re working on, how you’re progressing on your timelines, what you’ve accomplished, when you’ll be offline, and how you’re doing. Whether you’re working toward a tight deadline together or are all working on different projects, this is crucial.

Provide clarity and feedback around goals, expectations, timelines, and tasks. Take meeting notes and document tasks so everyone is on the same page. Check in on progress and give regular feedback. You should do these in any workplace, but it’s especially important in the remote setting to have these touchpoints.

Schedule formal and informal check-ins. Since we can’t ask each other to coffee or lunch, run into each other in the halls, or stop by each other’s offices, in the remote setting you have to schedule those times. Make it part of your company culture to do it regularly. Mentorship also can fall by the wayside in the remote setting—make sure you’re setting up regular meetings together.

Recognize the impact of microaggressions and exclusion in a remote setting. It is usually more difficult to know what people are going through when remote. Some things to look for are someone not showing up to or contributing in meetings, or regularly not turning on video. If that’s happening, check in on them to see what’s going on. Find out how you can support them.

Work harder to collaborate and to bridge isolation. Remote collaboration isn’t always simple. Use collaborative documents, innovation platforms, and other ways to get people involved and thinking in new ways. Some of my team will pair up and have coworking sessions via video to hold each other accountable and ask questions of each other when needed. Re-create the watercooler effect as well—you still need those moments to build empathy and understanding between individuals and across teams. These can be structured or unstructured weekly moments to get to know each other better.

Help new team members learn the culture. In a remote workplace, it can be more difficult to navigate the culture, systems, and processes. Help people navigate through the first few weeks, and check in with them once a month after that to make sure they are feeling welcome and finding their place on the team.

What Is Performative Allyship?

Performative allyship is saying you’re an ally without putting the action behind it. It’s professing your alliance to the cause of a group without doing anything in service of that group. Sometimes it’s wanting to be an ally or to be perceived as an ally, but when it comes down to it, you aren’t present when you’re needed.

Several brands showed performative allyship after George Floyd was murdered, for example. Knowing the Black Lives Matter movement was important to their customers, they released statements in solidarity. Many people called attention to the NFL for their Black Lives Matter statement and playing of the Black National Anthem, while still having low diversity numbers and not correcting the censuring of Colin Kaepernick. If you see brands performing without taking action, work to hold them accountable to their statements—make it known that as a customer, you care about the actions behind those statements.

Allyship is more than intention. It is more than words and positioning yourself as an ally. Allyship is earned based on learning, getting uncomfortable, going past any fears you may have, and taking action that benefits people with underrepresented identities. Allies do the work.

How Do I Lead the Change Without Taking the Spotlight?

There is a fine line between being recognized as an ally and overpowering the voices of the people you set out to be an ally for. Allies, advocates, accomplices, and activists take the responsibility of a cause or issue as their own, while at the same time following the lead of the person or group they’re advocating for and with.

My friend and colleague Corey Ponder says that allies should be “trusted sidekicks,” like Robin to Batman, Maria Rambeau to Captain Marvel, Okoye to Black Panther, Steve Trevor to Wonder Woman, Bucky Barnes and Falcon to Captain America.12 Allies are not saviors swooping in and taking the spotlight as they save the day, they are correctors—collaborating side by side to solve daily systemic inequities. Lend your power, influence, and privilege—and be humble. Speak up and speak out for change and for greater allyship. But rather than speaking for a group, whenever possible amplify the voices of that group to speak for themselves.

Something Not Here That You Really Want to Know?

If you still have a question, check out my podcast “Leading With Empathy & Allyship” and other resources, or find me on social media, attend one of our events or trainings, and reach out and ask. If I can, I’ll address it on my podcast or message you directly. You might also reach out to a colleague who is focused on DEI; they may be happy to help you. And of course, do your own research—the answer might be out there waiting for you.

Focus on Solutions

Being an ally can stretch us in new ways. Have the courage to take risks, make mistakes, and keep growing as an ally. Hold on to your motivation when times are challenging, stay true to your values, and focus on solutions.

In DEI and allyship work, we can get caught up in the deep problems we’re working to correct. The problems are what got us here, the solutions are what will take us to the next stage together. Recognize the problems, understand them—but don’t get stuck there. Focus on doing the work to fix them. Learn, show empathy, and take action.

I believe in you, and the collective impact we can make together, to build stronger, happier workplaces—and a better world where we can all thrive equally. One person at a time, one action at a time, one word at a time.

Thank you for your work.

EXERCISE