CHAPTER 2

The Network Mindset

You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.

—BUCKMINSTER FULLER, A Fuller View

Once you begin to recognize the webs of relationships that make up our world, you will never go back. This is what we call the network mindset shift. To adopt a network mindset is to embrace the reality that everything is connected—that the actions of individuals, organizations, and sectors affect one another in profound and often-unexpected ways. The network mindset is, more than anything, characterized by “a way of looking at the world, a shift in perspective . . . to see it relationally,” Christopher Vitale writes in Networkologies.1 Making this mindset shift is an essential step in the journey of thinking, learning, and working through networks to create change.

Those who have embraced the network mindset see themselves as part of a larger web of activity—as one of many nodes in the system, not the central hub. In this way, the network mindset shift can also be characterized as an evolution of focus from me to we, or from “ego-system awareness” to “eco-system awareness,” as Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer put it in Leading from the Emerging Future.2 With this shift, leaders become adept at noticing how their efforts are related to others, and as a result it becomes easier to identify opportunities to work together. Rather than trying to scale up an individual organization, building an increasingly large and efficient machine, they instead seek to scale out, developing stronger connections to generate impact through collaboration. This way of thinking and working is absolutely crucial for our ability to engage effectively with complexity. The potential for impact increases significantly when all types of resources—leadership, money, and talent—are leveraged across systems toward a common purpose.

The network mindset is captured most succinctly by four principles championed by Jane Wei-Skillern.3 Leaders who have adopted a network mindset focus on the following:

• Scaling impact, not growing their organization or function

• Being part of an interconnected system, not the center of it

• Sharing leadership and credit with peers, not hoarding power or trying to be a hero

• Building trust-based relationships, not systems of control

When you embrace a network mindset, you stop working in isolation. Instead, you turn your focus toward cultivating connections, strengthening flows, and sharing resources to do more together than is possible alone.

The Hierarchical Mindset

The dominant organizational framework in the world today is a hierarchical, command-and-control model where decisions are made by a small group of leaders and passed along to those lower in the chain of command. Hierarchies, defined as “a system or organization in which people or groups are ranked one above the other according to status or authority,”4 have an extraordinary capability to efficiently pursue and accomplish specific, well-defined ends, such as producing goods and services. They are most effective when addressing what Ron Heifetz calls “technical challenges”—those in which the problem definition, solution, and implementation are clear.5

Hierarchies are preferred by many for their predictability and stability—workers and leaders know what they can expect, and activities can be forecast well in advance. On the other hand, hierarchical structures are limited in their ability to address complex and multifaceted issues. Whereas networks work from the inside out, with ideas and actions emerging from the conversations happening between individuals, hierarchical structures operate from the top down, with powerful leaders sending instructions and resources to those lower in the hierarchy through layers of management. In the face of complexity, this structure turns into a bottleneck.

While a hierarchy is usually depicted as a pyramid, as seen in figure 2.1, we can also visualize it as a rigid hub-and-spoke network, as shown in figure 2.2. Imagine the CEO as the central node, with the links representing their relationships to their direct reports and their direct reports having links to additional direct reports, and so on. With each link, you move farther away from the central hub.

FIGURE 2.1. A hierarchical structure, as is typically depicted as a pyramid.

FIGURE 2.2. A hierarchical structure, drawn as a hub-and-spoke network.

Being near the top of a hierarchy (or the center of a rigid hub-and-spoke network) has its benefits—you have more control and are more likely to be needed. It also has its costs. The more you control, the less people are able to self-organize to advance work on their own. The more you are needed, the less resilient the system is in the event that you are unavailable. The more you preserve the hierarchical structure, the more you create a bottleneck and constrict the free flow of information. Being critically needed and in control is a double-edged sword.

This is a big part of why hierarchies have a hard time adapting quickly to changing circumstances. When the organizing structure is predefined and inflexible, there is little room for collective discovery, spontaneous collaboration, and unforeseen innovation. Hierarchies are good at achieving the specific ends they were set up to achieve, but they are not well suited to addressing complex issues that have no readily apparent solution.

For these reasons, hierarchical structures are a poor choice for multistakeholder collaborations. By holding on to control, the people at the top of hierarchies limit the self-organizing potential of the rest of the system. By maintaining a rigid structure that ranks some people over others, hierarchies create unequal access to information and power, which erodes trust. And in collaborative environments, there is often no central authority or shared governing body capable of directing the many diverse stakeholder groups involved. Or worse, there is a single point of command whose response imposes too much bureaucracy and fails to incorporate the diverse perspectives required to navigate complexity.

The most effective collaborative efforts we’ve seen feature a highly connected network organized around shared purpose and relationships, with flexibility embedded in the network’s structure. Building multistakeholder collaborations that thrive looks less like building structures that mimic hierarchical organizations and more like cultivating dynamic and interconnected networks.

Networks and Hierarchies, Together

In many cases, it’s not possible or wise to get rid of an existing hierarchical structure. Hierarchies exist for a reason. They are predictable and reliable, and they’re very good at executing strategies when it’s clear what needs to be done. So, rather than changing their internal structure, some organizations have supported networks to work alongside the existing hierarchy. As described earlier, impact networks are particularly well suited to addressing complex or systemic issues that don’t have a clear solution and for pursuing opportunities that require greater levels of collaboration between sites or departments, or with external stakeholders. These conditions are what inspired the launch of the Food Lab at Google.

When Michiel Bakker first arrived at Google as the leader of the Food team, he found it to be a very inward-looking organization. To make a broader impact on some of the biggest, most complex issues that Google cared about, Bakker saw the need to foster connections across the Google system as well as with people from the outside.

With Bakker’s leadership, Google launched the Food Lab in 2012 to address critical food system issues and to inspire its employees to develop more sustainable lifestyles. Since then, the Food Lab has brought people together from all levels of the Google organization, along with external experts and leaders. Convening twice per year, they apply their collective knowledge to key focus areas, including moving food culture toward a more plant-forward diet, increasing transparency in the food system, and reducing plastic waste.

To support this network, Google offers its resources to provide facilitation, convening space, and operational support. This points to a hybrid implementation—an impact network is created for process and action, while the hierarchy contributes to administration and reporting.

The Food Lab has facilitated new relationships across the Google system, with participating employees coming from many different departments and all levels of the organization, excited to have the chance to contribute to an issue they care deeply about. The Food Lab has also shaped Google’s strategic work. “When you bring together multiple points of view, you come up with solutions you never would have thought of alone,” shares Bakker. “The Food Lab has provided a much deeper understanding of the challenges and the opportunities, while leading to partnerships that would not have existed prior.”6

Employee networks (also known as employee resource groups, or ERGs) provide a more common example of cross-organizational networks. These identity- or experience-based networks provide space for people to support one another and pursue shared goals and interests, such as equal pay, professional development, or greater visibility in the organization. Nike, for example, has eight employee networks, including the Black Employee Network, the PRIDE Network, and the Women of Nike.7

Intra-organizational networks can create a sense of belonging among employees, even when they work in different departments or at different sites. These networks can even provide some of the strongest personal connections that employees experience in a company due to the focus on common experiences and shared needs. Employee networks can be a tremendous resource for the organization as a whole, helping to create more equitable policies, retain talent, increase employee satisfaction, and develop more inclusive products. While these groups are often self-organized, they may be provided financial or logistical support from the organization.

Networks such as Google’s Food Lab and employee networks serve organizations in ways that their existing hierarchies cannot. In addition to the specific outcomes that networks can achieve, they provide organizations with a means to unlock the creativity and engagement of their people. They do so in large part by offering meaningful opportunities for employees to contribute to something they care about but that falls outside the scope of their day-to-day responsibilities.

As the examples above illustrate, networks and hierarchies are not at odds with one another. They can work alongside each other in harmony. Although we are distinguishing the network mindset from the hierarchical mindset, in practice hierarchies and networks overlap and interact in important ways. All organizations—even hierarchical organizations—contain organic and informal networks that connect people and departments together. These networks are “intricately intertwined with an organization’s performance, the way it develops and executes strategy, and its ability to innovate,” write Rob Cross and Andrew Parker in The Hidden Power of Social Networks.8 Their research shows that “well managed network-connectivity is critical to performance, learning, and innovation.”9

Likewise, all networks contain natural hierarchies. Rather than having a single hierarchy dictate authority, networks have multiple flexible hierarchies that arise according to the specific context. This is what’s known as a heterarchical structure. In a heterarchy, formal power and decision-making is distributed—nobody has a baked-in, structural advantage over others. At the same time, some people may have more influence than others on specific issues based on their knowledge, experience, or role.

In my work with Sterling Network NYC, an action network working to advance economic mobility across the five boroughs of New York City, I noticed how one participant was a particularly trusted source for information about public housing because of their expertise and history as a leader in the sector. They were at the top of the public housing expertise hierarchy but lower on others. Another person was a skilled social justice lawyer and was influential on the topic of criminal justice reform. Meanwhile, a tech-savvy participant was the most influential on the question of what tech tools the network should adopt. By allowing multiple, natural hierarchies to emerge—rather than having a single power hierarchy dictating authority—impact networks unleash the many gifts that people bring to the group.

Making the Mindset Shift

For many people, it feels natural to work relationally, through networks. For others who have worked exclusively in hierarchical organizations their whole lives, shifting into a network mindset can take some time, given how it contrasts with Western assumptions of how change happens through deliberate planning and control. Key distinctions between the hierarchical and network mindsets are outlined in the table on the next page.

To use a metaphor from nature, impact networks are more like a murmuration of starlings than a flying V of geese. Network members do not have to move in the exact same direction at the exact same speed to get where they want to go, as geese do. Rather, they move independently while staying in close communication with one another, adjusting their own actions based on the movements of their closest neighbors. The murmuration of starlings shows us the power of social synergy, where many individual parts come together, and through their interactions something emerges that is creative, exciting, and new.

Hierarchical Mindset |

Network Mindset |

Mechanistic worldview |

Living systems worldview |

System seen as a hierarchical pyramid |

System seen as a web of interactions |

Organization at the center of focus |

Purpose at the center of focus |

Top-down, directive leadership |

Distributed, servant leadership |

Centralized decision-making |

Collective decision-making |

Impulse to command and control |

Impulse to connect and collaborate |

Information restricted |

Information shared |

Task oriented |

Relationship oriented |

Bias toward deliberate strategy |

Embrace of emergent strategy |

Distinctions between the hierarchical mindset and the network mindset.

One of the main implications of shifting to a network mindset is in how we think about leadership. Hierarchical leadership is directive and consolidates control. Power is centralized and is to be sought or guarded. In contrast, network leadership is facilitative, generating connections between others and decentralizing power such that people can organize without a top leader. While hierarchical leaders focus on the quantity and quality of their own relationships with others, network leaders focus on increasing the quantity and quality of relationships between others.

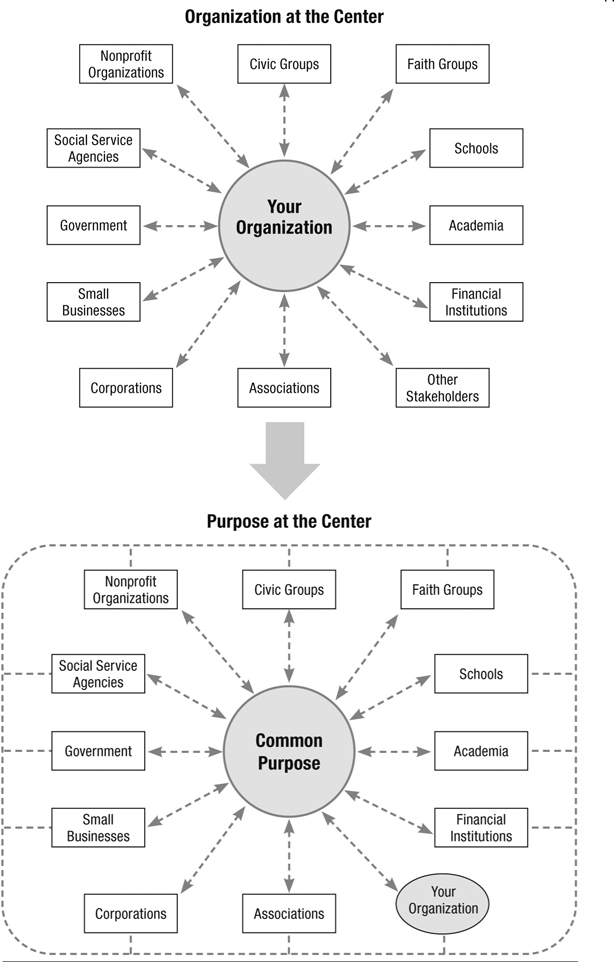

Similarly, it’s common for hierarchical leaders to think of themselves (or their organizations) as the sun, sitting at the center of their universe with all the other actors floating around them like orbiting planets. They are the hero of their own story, with others relegated to secondary roles. Leaders who have adopted a network mindset, however, recognize that they are part of a larger interconnected system. Rather than only looking inward, with an intense focus on internal metrics and financial goals, they look outward, beyond the walls of their organization. They act with an awareness of the whole system, becoming intimately connected with other groups who share their concerns. They put the pursuit of purpose at the center of their focus, rather than the growth of their own organization. This shift is reflected in figure 2.3.

The shift from a hierarchical mindset to a network mindset also changes the way we think about strategy. Hierarchical systems commonly adopt plan-and-deliver strategies. This can be seen in the ritual of developing long and detailed strategic plans. But complex situations defy the cause-and-effect relationships that strategic plans specialize in. Addressing complex issues requires experimentation, learning, and flexibility. Deliberate and emergent strategies are both necessary to balance planning with adaptation.

When groups of people share their different perspectives and blend their ideas together, new possibilities arise that could not have been predicted. Just as our brains exhibit extraordinary characteristics far beyond what we could predict from studying the electrical impulses of their individual neurons, and in the same way that the many surprising properties of water could not be predicted or understood by only looking at hydrogen and oxygen molecules on their own, networks cannot be understood by looking merely at their individual parts. It is in the interactions between the parts that something new is created. This process is, in a word, emergence. Emergence is the magical quality that gives networks their exponential potential for impact.

To tap into the boundless creativity that emerges when people from different parts of a system interact with one another, network leaders avoid the pull of authoritative decision-making.

FIGURE 2.3. With a hierarchical mindset, your organization is at the center of your focus. With a network mindset, you place the purpose at the center of your focus and see your organization as one part of a larger, interconnected system. This graphic is based on diagrams developed by Jane Wei-Skillern and Marty Kooistra.

Instead, they lean into emergence, supporting the network to self-organize into a vibrant ecosystem—full of connection, learning, and collaborative action—without unilaterally controlling its path.

Self-organizing happens when people are invited to notice and act on opportunities based on their own judgment. When people are free to try new things, initiate experiments, and connect and collaborate with others from across the system, networks become “leader-ful.”10 Whereas opportunities for leadership in a hierarchy correspond to one’s position in the structure, in a network, opportunities for leadership arise everywhere. Everyone has the agency to step in and advance projects they have energy for. As a result, responsibilities for the outcomes of the system are shared, and people recognize that they can have a hand in shaping the future. This is a big change from most hierarchical systems, where a small leadership group is entrusted to make sense of what is happening and plan out what comes next.

There is a common misconception that self-organization means something like spontaneous self-generation, but self-organization does not happen randomly or by sheer luck. Instead, the self-organizing potential of a network is fostered by servant leaders (to borrow a term coined by Robert Greenleaf11) who cultivate the conditions for connection, learning, and action to arise. These leaders also ensure that this all happens not in a vacuum but in relationship to a clear purpose that people can orient toward. As a result, while the actions of the group are likely to be quite varied in strategy and scope, they remain coherent and mutually reinforcing. In complex environments, coherent self-organization is a critical force, combining diverse perspectives and enabling widespread experimentation for a common good.

Fundamentally, the role of network leaders is to help diverse groups find the shared purpose that unites them, to foster self-organization, and to coordinate the actions that emerge so that they inform and reinforce one another. We may not be able to predict how to best address complex challenges, but through the emergent and self-organizing capacity of networks, we can learn our way into the future, together.