Chapter 7

Partnering for Performance

At its best, leadership is a partnership that involves mutual trust between two people who work together to achieve common goals. Both leader and follower influence each other. Leadership shifts between them, depending on the task at hand and who has the competence and commitment to deal with it. Both parties play a role in determining how things get done.

Partnering for performance, the third skill of effective situational leaders, provides a guide for creating such side-by-side leadership relationships. It is a process for increasing the quality and quantity of conversations between managers and direct reports—the people they support and depend on. These conversations not only help people perform better, but they also help everyone involved feel better about themselves and each other.

Establishing an Effective Performance Management System

An effective performance management system has three parts:

• Performance planning. After everyone is clear on the organizational vision and direction, performance planning begins. During this time leaders agree with their direct reports about the goals and objectives they should be focusing on. At this stage it’s okay for the traditional hierarchy to be alive and well, because if there’s a disagreement between a manager and a direct report about goals, who wins? The manager, because that person represents the organization’s goals and objectives.

• Performance coaching. This is where the hierarchy is turned upside down on a day-to-day basis. Now leaders do everything they can to help direct reports be successful. Servant leadership kicks in at this stage. Managers work for their people, praising progress and redirecting inappropriate performance.

• Performance review. This is where a manager and direct report sit down and assess the direct report’s performance over time.

Which of these three—performance planning, performance coaching, or performance review—do most organizations devote the greatest amount of time to? Unfortunately, it’s performance review. We go into organization after organization, and people say to us, “You’ll love our new performance review form.” We always laugh, because we think most of them can be thrown out. Why? Because these forms often measure things nobody knows how to evaluate. For example, “initiative” or “willingness to take responsibility.” Or “promotability”—that’s a good one. When no one knows how to win during a performance review, they focus most of their energy up the hierarchy. After all, if you have a good relationship with your boss, you have a higher probability of getting a good evaluation.

Some organizations do a good job on performance planning and set very clear goals. However, after goal setting, what do you think happens to those goals? Most often they get filed, and no one looks at them until they are told it’s time for performance reviews. Then everybody runs around, bumping into each other, trying to find the goals.

Of the three aspects of an effective performance management system, which one do people spend the least time on? The answer is performance coaching. Yet this is the most important aspect of managing people’s performance, because it’s during performance coaching that feedback—praising progress and redirecting inappropriate behavior—happens on an ongoing basis.

In Helping People Win at Work: A Business Philosophy Called “Don’t Mark My Paper, Help Me Get an A,” Ken Blanchard and WD-40 Company CEO Garry Ridge discuss in detail how an effective performance management system works.1 The book was inspired by Ken’s ten-year experience as a college professor. He sometimes got in trouble when he gave the students the final exam at the beginning of the course. When the faculty found out about that, they asked, “What are you doing?”

Ken said, “I thought we were supposed to teach these students.”

The faculty said, “You are, but don’t give them the final exam ahead of time!”

Ken said, “Not only will I give them the final exam ahead of time, what do you think I’ll do throughout the semester? I’ll teach them the answers so that when they get to the final exam, they’ll get As. You see, life is all about getting As—not some stupid normal distribution curve.”

Do you hire losers? Do you go around saying, “We lost some of our best losers last year, so let’s hire some new ones to fill those low spots.”? No! You hire either winners or potential winners. You don’t hire people to fit a normal distribution curve. You want to hire the best people possible, and you want them to perform at their highest level.

Giving people the final exam ahead of time is equivalent to performance planning. It lets people know exactly what’s expected of them. Teaching direct reports the answers is what performance coaching is all about. If you see people doing something right, you give them an “attaboy” or “attagirl.” If they do something wrong, you don’t beat them up or save your feedback for the performance review. Instead, you say, “Wrong answer. What do you think would be the right answer?” In other words, you redirect them. Finally, giving people the same exam during the performance review that you gave them at the beginning of the year helps them win—get a good evaluation. There should be no surprises in an annual or semiannual performance review. Everyone should know what the test will be and should get help throughout the year to achieve a high score on it. When you have a forced distribution curve—where a certain percentage of your people have to be average or less—you lose everyone’s trust. Now all people are concerned about is looking out for number one.

After learning about this philosophy, Ridge implemented “Don’t Mark My Paper, Help Me Get an A” as a major theme in his company. He is so emphatic about this concept that he would fire a poor performer’s manager rather than the poor performer if he found out that the manager had done nothing to help that person get an A.

Not all managers are like Garry Ridge. Many still believe you need to use a normal distribution curve that grades a few people high, a few people low, and the rest average. The reason these managers and their organizations are often reluctant to discard the normal distribution curve is that they don’t know how they will deal with career planning if some people don’t get sorted out at a lower level. If they rated a high percentage of their people as top performers, they wonder how they can possibly reward them all. As people move up the hierarchy, aren’t there fewer opportunities for promotion? We believe that question is quite naïve. If you treat people well and help them win in their present position, they often will use their creativity to come up with new business ideas that will expand your vision and grow the organization. Protecting the hierarchy doesn’t do your people or your organization any good.

Ralph Stayer, coauthor with Jim Belasco of Flight of the Buffalo, tells a wonderful story that proves this point. Stayer was in the sausage manufacturing business. His secretary came to him one day with a great idea. She suggested that they start a catalog business, because at the time they were direct-selling their sausages to only grocery stores and other distributors. He said, “What a great idea! Why don’t you organize a business plan and run it?” Soon the woman who used to be his secretary was running a major new division of his company and creating all kinds of job opportunities for people, as well as revenue for the company.2

Leadership that emphasizes judgment, criticism, and evaluation is a thing of the past. Leading at a higher level today is about helping people get As by providing the direction, support, and encouragement they need to be their best.

Partnering and the Performance Management System

To give you a better sense of how this works, we want to share with you a game plan that will help you understand how partnering for performance fits into the formal performance management system we just described. While you can put this game plan into action with no prior training, it is much more powerful when everyone involved—both leaders and direct reports—understands Situational Leadership® II or Situational Self Leadership. That ensures that everyone is speaking the same language.

Performance Planning: The First Part of a Performance Management System

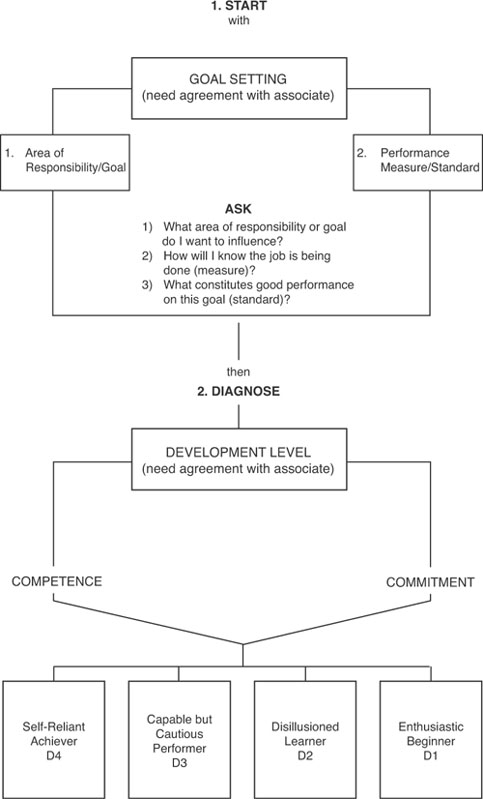

As you can see in Figure 7.1, the first three steps in the Partnering for Performance Game Plan—goal setting, diagnosis, and matching—begin the performance process.

Figure 7.1 The Partnering for Performance Game Plan

The first key element of effective partnering for performance is goal setting. All good performance starts with clear goals. This is such an important concept that we discuss it in detail in Chapter 8, “Essential Skills for Partnering for Performance: The One Minute Manager.” Clarifying goals involves making sure that people understand two things: first, what they are being asked to do—their areas of accountability—and second, what good performance looks like—the performance standards by which they will be evaluated.

Diagnosis is the second element of partnering for performance. It starts with the leader and direct report individually diagnosing the direct report’s development level for each of the goals agreed on. When we say individually, we mean that both leader and direct report go to a quiet place and separately diagnose the development level for each goal area by asking two questions:

• To determine competence, each should ask, “Does this person/do I know how to do this task?”

• To determine commitment, each should ask, “How excited is my direct report/am I about taking this on?”

After both people in the partnering process have done their diagnostic homework, they should come back together and agree on who goes first. If the direct report goes first, the leader’s job is to listen to that person’s diagnosis. Then, before saying anything else, the leader has to tell the direct report what she heard him saying until he agrees that’s what he said. When it’s the leader’s turn, she tells the direct report her diagnosis of his development level on each of his areas of responsibility. His job is now to listen and feed back what he heard until his manager agrees that’s what she said. Why do we suggest this process? Because it guarantees that both people are heard. Without some structure like this, if one of the two people involved is more verbal than the other, that person will dominate the conversation.

After both people have been heard, they should discuss similarities and differences in their diagnoses and attempt to come to some agreement. If there is a disagreement between leader and direct report on development level that cannot be resolved, who should win? The direct report. It is not the manager’s job to fight over development level. However, the manager should make the direct report accountable. This means asking him, “What will you be able to show me in this goal area in a week or two that will demonstrate that your development diagnosis was right?” You want to help your people win, even if agreement has not been reached. We have found that people will work hard to prove they are right, which is exactly what you want them to do. If performance does not live up to agreed-on expectations, it will be clear to the direct report that the diagnosis should be reconsidered, and more direction and/or support should be given.

Once development level is clear, both parties, if they know Situational Leadership® II, should be ready to discuss which leadership style is needed. This leads to matching, the third step in the partnering for performance game plan. Matching ensures that the leader provides the kind of behaviors—a leadership style—that the direct report needs to perform the task well and, at the same time, enhances his commitment.

While the appropriate leadership style to use should be clear once development level is determined, that’s just the beginning. When you’re partnering for performance, you don’t just leave it at saying you’ll use a delegating or coaching style. You have to be more specific. For the leader, this provides an opportunity for what we call “getting permission to use a leadership style.”

The purpose of getting permission to use a leadership style is twofold. First, checking to make sure that the style proposed is what the direct report agrees he needs creates clarity. Second, getting permission ensures the direct report’s buy-in on the use of that style and increases his commitment. For example, if a direct report is an enthusiastic beginner who does not have much in the way of task knowledge and skill, but is excited about taking on the task, this person obviously needs a directing leadership style. The leader might say, “How would it be if I set a task goal that I believe will stretch you but is attainable, and then develop an action plan for you that will enable you to reach the goal? Then I’d like to meet with you on a regular basis to discuss your progress and provide any help you need as you get started. Does this make sense as a way for you to get up to speed as quickly as possible?” If the direct report agrees, they are off and running.

On the other hand, suppose a direct report is a self-reliant achiever on a particular goal and therefore can handle a delegating leadership style. The leader might say, “Okay. The ball is in your court, but keep me in the loop. If you have any concerns, give me a call. Unless I hear from you, or the information I receive tells me otherwise, I’ll assume everything is fine. If it isn’t, call early. Don’t wait until the monkey is a gorilla. Does that work for you?” If the direct report says yes, he is on his own until his performance or communication suggests differently. If in either of the two examples—the enthusiastic beginner or the self-reliant achiever—the direct report doesn’t agree, what should happen? Further discussion should take place until a leadership approach is agreed on.

As you can tell from the examples, once an appropriate leadership style is agreed on, the leader still needs to provide work direction. Providing work direction might involve establishing clear performance expectations, creating an action plan, putting in place a process for checking progress, and expressing confidence that the person can deliver on the performance plan.

As part of that process, it’s important to establish a monitoring process based on the agreed-on leadership style. This is where the leader and direct report commit to holding scheduled meetings—called progress-check meetings—to discuss how performance is going.

For example, if you agree that your direct report needs a directing style, you would meet quite frequently and maybe have the direct report attend some formal training. If a coaching style is chosen, you might say, “Let’s schedule two meetings a week for at least two hours to work on the goal you need help with. How about Mondays and Wednesdays from 1 to 3 p.m.?” With a supporting leadership style, you might ask, “What’s the best way for me to recognize and praise the progress you are making? At lunch every week or so?” If you agree to have lunch together, your role would be to listen and support her actions. With a delegating style, it would be up to the direct report to request help, since she’s a self-reliant achiever.

Performance Coaching: The Second Part of a Performance Management System

Once it’s determined, the agreed-on leadership style establishes the number, frequency, and kind of progress-check meetings that leaders and their direct reports have with each other. The implementation of these meetings begins performance coaching. That’s where leaders praise progress and/or redirect the efforts of their partners—their direct reports.

Leaders often assume that their work direction conversations are so clear that there is no need for follow-up or that they are so busy that they can’t take the time. If you want to save yourself time and misery, schedule and hold progress-check meetings. You will be able to catch problems before they become major and significantly increase the probability that your direct report’s performance on the goal will meet your expectations. If they didn’t schedule progress-check meetings, leaders could set up their people for failure. That’s why one of our favorite sayings is

While this might sound intrusive, it really isn’t. As Ken Blanchard, Thad Lacinak, Chuck Tompkins, and Jim Ballard point out in Whale Done!: The Power of Positive Relationships, inspecting should emphasize catching people doing things right, not wrong. Praising progress and/or redirecting efforts begins with accentuating the positive. Redirection follows praising to keep progress going. If no progress is being made—in other words, if performance is not improving—leaders should move straight to redirection to stop any further decline in performance.

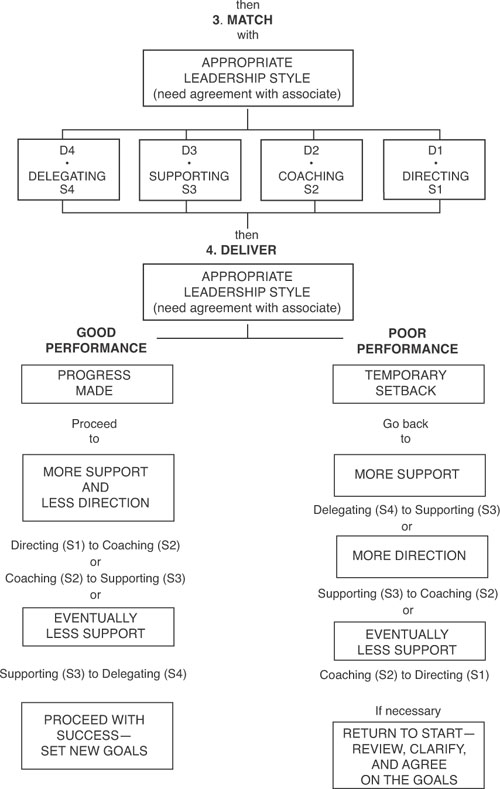

When they deliver the appropriate leadership style, managers are taking the fourth step in the partnering for performance game plan. Let’s take a look at the model again and see what happens when performance is improving.

Improving Performance

As you reexamine Figure 7.2, you might be wondering what the curve running through the four styles means. We call it a performance curve, and for good reason.

Figure 7.2 Situational Leadership® II Leadership Styles

As development level moves from enthusiastic beginner (D1) to self-reliant achiever (D4), the curve shows how a manager’s leadership style moves from directing (S1) to delegating (S4), with first an increase in support (S2), and then a decrease in direction (S3), until eventually there’s also a decrease in support (S4). At self-reliant achiever (D4), the person can direct and support more and more of his or her own work. Your goal as a manager, then, should be to help your direct report improve performance by changing your leadership style over time.

To help yourself do that as a leader, imagine the performance curve is a railroad track. Each of the four leadership styles depicts a station along the performance curve. If you start with an enthusiastic beginner (D1) using a directing style (S1), and you want to eventually get to delegating (S4), appropriate for a self-reliant achiever (D4), what two stations do you have to stop at along the way? Coaching (S2) and supporting (S3).

You’ll notice that no railroad tracks go straight from directing (S1) to delegating (S4). What happens to a fast-moving train if it goes off the tracks? People get hurt. It is important for managers not to skip a station as they manage people’s journey to high performance. By staying on track and stopping at all the stations, you will lead your direct reports to perform well on their own, with little or no supervision. Lao Tzu said it well:

When the best leader’s work is done, the people say, “We did it ourselves!”

An experiment we did at the University of Massachusetts illustrates the power of Situational Leadership® II in partnering for performance. We worked with four instructors teaching an eight-week course in management. The first two instructors taught by either lecturing or leading discussions—in other words, they used directing and coaching styles. These two traditional instructors became our control group.

We taught the other two instructors Situational Leadership® II and showed them how to change their teaching style over the course of eight weeks. The first two weeks we asked them to use a directing style: lecturing. The next two weeks we asked the instructors to lead discussions, in essence using a coaching style. During the following two weeks we showed them how to move to a supporting style by restricting their involvement in the class; they sat back and made only process comments like “Has everybody had a chance to speak?” or supportive comments like “This is a really interesting class.” During the last two weeks we showed them how to go to a delegating leadership style: they asked their students to run the class themselves, letting them know that they would be in the classroom next door writing an article for a business journal.

On the last day of class, a secretary came into all four classes and wrote a note on the whiteboard: “The instructor is sick tonight and won’t be here. Carry on as usual.”

What do you think happened to the students in the first two classes, where the control group instructors only lectured or led discussions? Within five minutes, those students were gone. Without the instructor there, they didn’t know what to do.

In the classes with the changing leadership style, nobody left. Students made comments like “The instructor hasn’t been here for the last two weeks. Big deal. What did you think about that case?” One of the two classes even stayed a half hour beyond the scheduled time.

At the end of the semester, the experimental classes with the changing teaching style outperformed the other two classes. The students knew more, they liked the course better, and they weren’t late or absent. How was that possible when their instructors weren’t even there for the last two weeks? Because the instructors stayed on the railroad tracks and gradually changed their teaching style from directing to coaching to supporting to delegating, the students over time moved from dependence to independence, from enthusiastic beginners to self-reliant achievers.

Declining Performance

We rarely find decreases in performance resulting from a decline in competence. Unless you can cite cases of Alzheimer’s at work, people generally don’t lose their competency if they had it in the first place or were trained to have it. Changes in performance occur either because the job and the necessary skills to perform it have changed, or because people have lost their commitment.

For the most part, leaders avoid dealing with their decommitted people, largely because it is such an emotionally charged issue and they don’t know how. When they do address it, they usually make matters worse: They turn the not-engaged into the actively disengaged. The core perception on the part of these decommitted people is that either their leader or the organization has treated them unfairly.

We believe that the primary reason for loss of commitment is the behavior of the leader and/or the organization. More often than not, something the leader or organization has done or failed to do is the primary cause of the eroded commitment.

Decommitted people are not provided with the kind of leadership that matches their needs—they are under- or oversupervised. Decommitment has numerous other potential causes: lack of feedback, lack of recognition, lack of clear performance expectations, unfair standards, being yelled at or blamed, reneging on commitments, being overworked and stressed out. The loss of commitment can affect most, if not all, of the person’s job functioning.

People often assume that decommitment occurs mainly at the bottom of the organization, with individual contributors. Not so. It occurs at every organizational level.

Current literature and training programs for addressing what is called “handling performance problems” are overwhelmingly focused on frontline leaders. This literature and these programs assume that the frontline employee is the problem. The language itself—“handling performance problems”—implies that the person with the problem is the problem. The literature and training programs emphasize issues such as employees’ unacceptable performance or behavior, documenting performance problems, developing organizational policies to deal with them, employee counseling, removing poor performers, corrective counseling, and discipline.3

In general, these are lose-lose strategies that intensify decommitment and that should be used only as a last resort. This approach is commonly called “blaming the victim.” A process that does not address all the causes of the problem is guaranteed not to work, particularly if the person who is blaming the performer has a hand in causing it. If the leader and/or organization have a role in causing the problem, their role has to be identified and resolved as part of the solution.

Placing Blame: Not a Good Strategy

First, let’s assume that either the leader or the organization has contributed to the cause of an individual’s decommitment. This is not always the case, but the evidence suggests that it is in the substantial majority of instances where decommitment has occurred. Next, let’s assume that the issue has been going on for some time. Again, evidence supports this assumption. When we ask leaders in organizations to identify the people they lead who have “performance problems” and to tell us how long this has been going on, the responses range from six months to ten years. These responses alone identify the leader as part of the problem: the issues are not being addressed.

Dealing with decommitment is a difficult and usually highly emotionally charged undertaking. If the situation has been going on for some time, a high level of emotional tension probably exists in the relationship between the leader and the direct report. The leader blames the direct report, and the direct report blames the leader and/or the organization.

A sophisticated set of interpersonal skills and the ability not to let your ego get in the way are required to effectively address the problem. If you are unwilling to own up to any behavior on your or the organization’s part that has contributed to the cause of the problem, resolution is unlikely.

Dealing with Decommitment

Decommitment occurs when a gap exists between the direct report’s performance and/or behavior and the leader’s expectations. This gap occurs for two primary reasons. First, a gap occurs when the person has demonstrated the ability to perform or behave appropriately, and now his performance has declined or his behavior has changed in a negative way. Second, a gap occurs when the person is unwilling to gain knowledge and/or skills that would lead to improved performance or behavior.

We see three possible strategies for addressing decommitment:

• Keep on doing what you’ve always done.

• Catch it early.

• Go to a supporting leadership style (high supporting/low directing leader behavior).

The first alternative—keep on doing what you’ve always done—will get you what you’ve always gotten: escalating anger, frustration, and no resolution.

The most effective alternative is to catch decommitment early—the first time it is observed, before it gets out of control and festers. Early detection makes it easier for both you and your direct report to identify the causes and resolve them.

Just as improvements in performance prompt forward shifts in style along the curve, decreases in performance require a shift backward in leadership style along the performance curve. If a person you are delegating to starts to decline in performance, you want to find out why. So, you would move from a delegating style to a supporting style, where you listen and gather data. If both of you agree that the direct report is still on top of the situation, can explain the decline in performance, and can get performance back in line, you can return to a delegating leadership style. However, if you both agree that this performance situation needs more attention from you, you now can go to a coaching style where you can provide closer supervision. Seldom, if ever, do you have to go all the way back to a directing style.

The third alternative for addressing decommitment when the problem has been going on for some time is to cautiously go to a supporting leadership style. That may seem inappropriate to impatient managers who would like to get off the railroad tracks and head straight back to a directing leadership style. Let’s explore why and how a supporting leadership style is a better choice.

Step 1: Prepare

Preparation should involve selecting a specific performance or behavior that you believe you have a chance of jointly dealing with. Do not attempt to address everything at once.

After you have pinpointed the performance or behavior you want to focus on, gather all the facts that support the existence of the performance or behavior from your point of view. If it is a performance issue, quantify the decline in performance. If it is a behavior issue, limit your observations to what you have seen. Don’t make assumptions or bring in the perceptions of others. This is a sure way to generate defensiveness. And you probably won’t be able to specifically identify these “others” anyway, because they usually don’t want to be named. Also, use the most recent information possible. Next, identify anything you or the organization might have done to contribute to the decommitment. Be honest. Owning up is the most important part of moving toward resolution.

Ask yourself questions to determine your role in the situation. Were performance expectations clear? Have you ever talked to the person about his or her performance or behavior? Does the person know what a good job looks like? Is anything getting in the way of performance? Have you been using the right leadership style? Are you giving feedback on the performance or behavior? Is the person getting rewarded for inappropriate performance or behavior? (Often people in organizations are rewarded for poor behavior—that is, nobody says anything.) Is the person getting punished for good performance or behavior? (Often people get punished for good performance or behavior—that is, they do well and someone else gets the credit.) Do policies support the desired performance? For example, is training or time made available to learn needed skills?

Once you have done a thorough job of preparing, you’re ready for Step 2.

Step 2: Schedule a Meeting, State the Meeting’s Purpose, and Set Ground Rules

Scheduling a meeting is vital. It is important to begin the meeting by stating the meeting’s purpose and setting ground rules to ensure that both parties will be heard in a way that doesn’t arouse defensiveness. Decommitted people with serious performance or behavior issues are very likely to be argumentative and defensive when confronted. For example, you might open the meeting with something like this:

“Jim, I want to talk about what I see as a serious issue with your responsiveness to information inquiries. I would like to set some ground rules about how this discussion proceeds so that we can both fully share our perspectives on the issue. I want us to work together to identify and agree on the issue and its causes so that we can set a goal and develop an action plan to resolve it.

“First, I would like to share my perceptions of the issue and what I think may have caused it. I want you to listen, but not to respond to what I say, except to ask questions for clarification. Then, I want you to restate what I said, to make sure you understand my perspective and I know you understand it. When I am finished, I would like to hear your side of the story, with the same ground rules. I will restate what you said until you know I understand your point of view. Does this seem like a reasonable way to get started?”

Using the ground rules you have set, you should begin to understand each other’s point of view on the performance issue at hand. Making sure that both of you have been heard is a wonderful way to reduce defensiveness and move toward resolution.

Once you have set ground rules for your meeting, you are ready for Step 3.

Step 3: Work Toward Mutual Agreement on the Performance Issue and Its Causes

The next step is to identify where there is agreement and disagreement on both the issue and its causes. Your job is to see if enough of a mutual understanding can be reached so that joint problem solving can go forward. In most conflict situations, it is unlikely that both parties will agree on everything. Discover if there is sufficient common ground to work toward a resolution. If not, revisit those things that are getting in the way, and restate your positions to see if understanding and agreement can be reached.

When you think it is possible to go forward, ask, “Are you willing to work with me to get this resolved?”

If you still can’t get a commitment to go forward, you need to use a directing leadership style. Set clear performance expectations and a time frame for achieving them; set clear, specific performance standards and a schedule for tracking performance progress; and state consequences for nonperformance. Understand that this is a last-resort strategy that may resolve the performance issue but not the commitment issue.

When you get a commitment to work together to resolve the issue, it is normal to feel great relief and assume that the issue is resolved. Not so fast.

If you or the organization has contributed to the cause of the problem, you need to take steps to correct what has been done. Anything you have done to cause or add to the problem needs to be addressed and resolved. Sometimes, you have no control over what the organization has done, but just acknowledging the organization’s impact often releases the negative energy and regains the other party’s commitment.

If you finally get a commitment to work together to resolve the issue, you can go to Step 4 and partner for performance.

Step 4: Partner for Performance

Now you and the direct report need to have a partnering for performance discussion in which you jointly decide the leadership style you will use to provide work direction or coaching. You should set a goal, establish an action plan, and schedule a progress-check meeting. This step is crucial.

Resolving decommitment issues requires sophisticated interpersonal and performance management skills. Your first try at one of these conversations is not likely to be as productive as you would like. However, if you conduct the conversation in honest good faith, it will reduce the impact of less-than-perfect interpersonal skills and set the foundation for a productive relationship built on commitment and trust.

Performance Review: The Third Part of a Performance Management System

The third part of an effective performance management system is performance review. This is where a person’s performance over the course of a year is summed up. We have not included performance review in the traditional sense in our partnering for performance game plan. Why? Because we think effective performance review is not an annual event, but an ongoing process that takes place throughout the performance period. When progress-check meetings are scheduled according to development level, open, honest discussions about the direct report’s performance take place on an ongoing basis, creating mutual understanding and agreement. If these meetings are done well, the year-end performance review will just be a review of what has already been discussed. There will be no surprises.

Partnering as an Informal Performance Management System

What we have been talking about so far is how partnering for performance could fit in with a formal performance management system. Unfortunately, most organizations don’t have a formal performance management system. Organizational goals are usually set, but often no system is established to accomplish them. As a result, the management of people’s performance is left to the discretion and initiative of individual managers. While annual performance reviews are usually done, they tend to be haphazard at best in most organizations. Managers working in that kind of environment can implement partnering for performance on an informal basis in their own areas, even when it comes to performance review. As we stated earlier, we believe that effective performance review is an ongoing process that should take place throughout the performance period, not just once a year. If managers do a good job with an informal performance review system, perhaps through their good example, a formal performance management system will emerge organization-wide, with partnering for performance as a core element.

One-on-Ones: An Insurance Policy for Making Partnering for Performance Work

How can people close the gap between learning about partnering for performance and really doing it?

Margie Blanchard and Garry Demarest developed a one-on-one process that requires managers to hold 15- to 30-minute meetings a minimum of once every two weeks with each of their direct reports.4 Since managers have more people to worry about than an individual contributor, the onus is on the direct report to schedule these meetings as well as set the agenda. This is when people can talk to their managers about anything on their hearts and minds—it’s their meeting. The purpose of one-on-ones is for managers and direct reports to get to know each other as human beings.

In the old days, most businesspeople had a traditional military attitude that said, “Don’t get close to your direct reports. You can’t make hard decisions if you have an emotional attachment to your people.” Yet rival organizations will come after your best people, so knowing and caring for them is a competitive edge.

Don’t let this be said about you. One-on-one meetings not only deepen the power of partnering for performance, they also create genuine relationships and job satisfaction. In the next chapter, we’ll reveal the final secrets of leading people one-on-one.