Chapter 11

Organizational Leadership

Just as team leadership is more complicated than one-on-one leadership, leading an entire organization is more complicated than leading a single team. Why? Because organizational leadership is all about leading change, and managing change is chaotic and messy.

Today we live in “permanent whitewater.” What do we know about whitewater? It’s both exhilarating and scary! You often have to go sideways or upside down to go forward. The flow is controlled by the environment. There are unseen obstacles. Occasionally it’s wise to use an eddy to regroup and reflect, but eddies are often missed because whitewater seems to create its own momentum.

The Importance of Managing Change

Once there was a time when you could experience change and then return to a period of relative stability. In that era, as things settled down, you could thoughtfully plan and get ready for another change. Kurt Lewin described these phases as unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. The reality today is that there is no refreezing. There’s no rest and no getting ready.

In the midst of this chaos, it’s hard for people to maintain perspective. The situation reminds us of the story about the little girl who comes home from school one day and asks her mother (although today it certainly could be her father), “Why does Daddy work so late every night?” The mother gives a sympathetic smile and replies, “Well, honey, Daddy just doesn’t have time to finish all his work during the day.” In her infinite wisdom the little girl says, “Then why don’t they put him in a slower group?” Alas, there are no slower groups. Constant change is a way of life in organizations today.

Mark Twain once said, “The only person who likes change is a baby with a wet diaper.” Like it or not, in the dynamic society surrounding today’s organizations, the question of whether change will occur is no longer relevant. Change will occur. That is no longer a probability; it is a certainty.

The issue is, how do managers and leaders cope with the barrage of changes that confront them daily as they attempt to keep their organizations adaptive and viable?

They must develop strategies to listen in on the conversations in the organization so that they can surface and resolve people’s concerns about change. They have to strategize hard to lead change in a way that leverages everyone’s creativity and ultimate commitment to working in an organization that’s resilient in the face of change.

Why Is Organizational Change So Complicated?

Consider what happens when someone takes a golf lesson. The instructor changes the golfer’s swing in an effort to improve his score. However, golfers’ scores typically get worse while they are learning a new swing. It takes time for golfers to master a new swing and for their scores to improve. Now, think about what happens when you ask each member of a team of golfers to change their respective swings at the same time. The cumulative performance drop is larger for the team than it is for any one golfer.

The same performance drop occurs in organizations where large numbers of people are asked to make behavior changes at the same time. When one person on a team is learning a new skill, the rest of the team can often pick up the slack and keep the team on track. However, when everyone is learning new skills, who can pick up the slack?

When a change is introduced in an organization, an initial drop in organizational performance typically occurs before performance rises to a level above the prechange level. Effective change leaders, being aware of this and understanding the process of change, can minimize the drop in performance caused by large numbers of people learning new behaviors at the same time. They can also minimize the amount of time to achieve desired future performance. Furthermore, they can improve an organization’s capacity to initiate, implement, and sustain successful changes. That’s exactly what we hope you will be able to learn from this chapter.

When Is Change Necessary?

Change is necessary when a discrepancy occurs between an actual set of events—something that is happening right now—and a desired set of events—what you would like to happen. To better understand where your organization might be in relation to needed change, consider the following questions:

• Is your organization on track to achieve its vision?

• Are your organization’s initiatives delivering the desired outcomes?

• Is it delivering those outcomes on time?

• Is it delivering those outcomes on budget?

• Is your organization maintaining high levels of productivity and morale?

• Are your customers excited about your organization?

• Are your people energized, committed, and passionate?

If you find it difficult to say yes to these questions, your focus on leading change should be more intense.

Most managers report that managing change is not their forte. In a survey of 350 senior executives across 14 industries, 68 percent confirmed that their companies had experienced unanticipated problems in the change process.1 Furthermore, research indicates that 70 percent of organizational changes fail, and these failures can often be traced to ineffective leadership.

Change Gets Derailed or Fails for Predictable Reasons

Our research and real-world experience have shown that most change efforts get derailed or fail for predictable reasons. Many leaders don’t recognize or account for these reasons. As a result, they make the same mistakes repeatedly. As is often said:

Fortunately, there is hope. If you recognize the reasons change typically gets derailed or fails, leadership can be proactive, thereby increasing the probability of success when initiating, implementing, and sustaining change.

When most people see this list, their reaction depends on whether they have usually been the target of change or the change agent. Targets of change frequently feel as though we have been studying their organization for years, because they have seen these reasons why change fails in action, up close and personal. The reality is that while every organization is unique in some ways, they often struggle with change for the same reasons.

When change agents look at this list, they get discouraged, because they realize how complicated implementing change can be and how many different things can go wrong. Where should they start? Which of the fifteen reasons why change fails should they concentrate on?

Over the years it has been our experience that if leaders can understand and overcome the first three reasons why change typically fails, they are on the road to being effective leaders of change.

Focus on Managing the Journey

In working with organizations for more than three decades, we have observed a leadership pattern that sabotages change. Leaders who have been thinking about a change for a while know why the change needs to be implemented. In their minds, the business case and imperative to change are clear. They are so convinced that the change has to occur that, in their minds, no discussion is needed. So they put all their energy into crafting their message and announcing the change and very little effort into involving others and managing the journey of change. They forget that:

In Situational Leadership® II terms, leaders who announce the change are using a directing style. They tell everybody what they want to have happen, and then disappear. Using an inappropriate delegating style, they expect the change to be automatically implemented. Unfortunately, that never happens. They are not managing the journey. As a result, the change gets derailed. Why?

Change gets derailed because people know they can outlast the announcement, or at least the person making the announcement. Because they haven’t been involved up to this point, they sense that the organization is concerned only with its own self-interests, not with the interests of everyone in the organization. Change that is done to people creates more resistance. The moment vocal resistance occurs, the people leading the change break ranks. The minute they do, their lack of alignment signals that there’s no need for others to align to the change, because it’s going nowhere.

A poor use of directing style, followed by an inappropriate delegating style—announcing the change and then abdicating responsibility for the change—means that the change will never be successfully implemented. Rather, take time to practice partnering for performance and involve those impacted by the change in every phase of the change process.

Surfacing and Addressing People’s Concerns

As we mentioned in Chapter 5, Situational Leadership® II applies whether you are leading yourself, another individual, a team, or an organization. In the self and one-to-one context, the leader diagnoses the competence and commitment of a direct report on a specific task. In the team context, a leader diagnoses the team’s productivity and morale. In the organizational context, the focus is on diagnosing the predictable and sequential stages of concern that people go through during change.

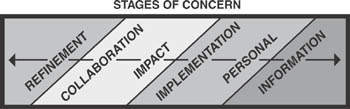

A U.S. Department of Education project originally conducted by Gene Hall and his colleagues at the University of Texas2 suggests that people who are faced with change express six predictable and sequential concerns (see Figure 11.1):

Figure 11.1 The Stages of Concern Model

People going through a change often ask questions that give leaders clues about which stage of concern they are in. Most of the time, the people managing a change don’t hear these questions because there are no forums for people to express them. Or, if there are forums, the communication is one way. Those impacted by the change have little to no opportunity to question the reasons for the change or what the change will look like when it’s implemented. So, instead of becoming advocates for the change because their concerns are surfaced and addressed, those impacted by the change become resistant to it.

Let’s look at each stage of concern and the questions people are asking themselves and their peers.

Stage 1: Information Concerns

At this stage, people ask questions to get information about the change. For example: What is the change? Why is it needed? What’s wrong with the way things are now? How much and how fast does the organization need to change?

People with information concerns need the same information used by those who decided to move forward with the change. They don’t want to know if the change is good or bad until they understand it. Assuming that the rationale for change is based on solid information, share this information with people, and help them see what you see. Remember, in the absence of clear, factual communication, people tend to create their own information about the change, and rumors become facts.

In a SAP3 implementation where the change leadership team had done a good job explaining the business case, people said: “Fewer errors will occur with a single data entry. It will save money, because we will eliminate double entries. Fewer steps will be needed, and more functionality and collaboration will occur across work groups. It will be ten times easier to access information. In the long run, it will save time, because things will be done in the background. It will eliminate redundancy.”

Their information concerns were largely answered by the data the leadership team provided them through multiple vehicles.

Stage 2: Personal Concerns

At this stage, people ask questions about how the change will affect them personally. For example: What’s in it for me to change? Will I win or lose? Will I look good? How will I find the time to implement this change? Will I have to learn new skills? Can I do it?

People with personal concerns want to know how the change will play out for them. They wonder if they have the skills and resources to implement the change. As the organization changes, existing personal and organizational commitments are threatened. People are focused on what they are going to lose, not gain.

These personal concerns have to be addressed in such a way that people feel they have been heard. As Werner Erhard often said, “What you resist, persists.” If you don’t permit people to deal with their feelings about what’s happening, these feelings stay around. The corollary to this principle is that if you deal with what is bothering you, in the very process of dealing with your feelings, the concerns often go away. Have you ever said to yourself, “I’m glad I got that off my chest”? If so, you know the relief that comes from sharing your feelings with someone. Just having a chance to talk about your concerns during change clears your mind and stimulates creativity that can be used to help rather than hinder change efforts. This is where listening comes in. Leaders and managers must permit people to express their personal concerns openly, without fear of evaluation, judgment, or retribution.

In some cases, personal concerns are not resolved to an individual’s satisfaction, but the act of listening to these concerns typically goes a long way toward reducing resistance to the change effort.

If you don’t take time to address individual needs and fears, you won’t get people beyond this basic level of concern. For that reason, let’s look at some of the key personal concerns people often have with regard to change.

People are at different levels of readiness for change. Although almost everyone experiences some reluctance to change because they are not really sure how the change will impact them personally, some individuals may quickly get excited by an opportunity to implement new ideas. Others need some time to warm up to new challenges. This doesn’t mean there’s any one “right” place to be on the readiness continuum; it just means that people have different outlooks and degrees of flexibility about what they’ve been asked to do. Awareness that people are at different levels of readiness for change can be extremely helpful in effectively implementing any change effort. It helps you identify “early adopters” or change advocates who can be part of your change leadership team. This awareness will help you reach out to those who appear to be resisting the change. Their reasons for resisting may represent caution, or they could be clues to problems that have to be resolved if the change is to be successfully implemented.

People initially focus on what they have to give up. People’s first reaction to a suggested change often tends to be a personal sense of loss. What do we mean by “losses”? These include, among other things, the loss of control, time, order, resources, coworkers, competency, and prestige. To help people move forward, leaders need to assist them in dealing with this sense of loss. It may seem silly, but people need to be given a chance to mourn their feelings of loss, perhaps just by having time to talk with others about how they feel. Remember, what you resist persists. Getting in touch with what you think you will be losing from the change will help you accept some of the benefits.

Ken Blanchard and John Jones, cofounder of University Associates, worked with several divisions of AT&T in the early 1980s during the breakup of the corporation into seven separate companies.4 When they announced it, the leaders of this change started out by talking about the benefits. Ken and John realized that nobody could hear these benefits at that time, because people’s personal concerns had not been dealt with. To resolve this, they set up “mourning sessions” throughout these divisions where people could talk openly about what they thought they would have to give up with this change. The following were the biggest issues that surfaced:

Loss of status. When you asked people at that time who they worked for, their chests would puff out as they said, “AT&T.” It just had a much better ring to it than “Jersey Bell” or “Bell South.”

Loss of lifetime employment. A classmate of Ken’s, after he graduated from Cornell, got a job with AT&T. When he called home to tell his mother, she cried with joy. “You’re set for life,” she said. In those days, if you got a job with AT&T, the expectation was that you would work for them for thirty or thirty-five years, have a wonderful retirement party, and then ride off into the sunset. In these days of constant change, people have personal concerns about long-term employment.

Ken and John found that after people had expressed their feelings about these kinds of losses, they were much more willing and able to hear about the benefits of divestiture.

People feel alone even if everyone else is going through the same change. When change hits, even if everyone around us is facing the same situation, most of us tend to take it personally: “Why me?” The irony is that for the change to be successful, we need the support of others. In fact, we need to ask for such support. People are apt to feel punished when they have to learn new ways of working. If change is to be successful, people need to recruit the help of those around them. We need each other. This is why support groups work when people are facing changes or times of stress in their lives. They need to feel that their leaders, coworkers, and families are on their side in supporting the changes they need to make. Remember, you can’t create a world-class organization by yourself. You need the support of others, and they need your support, too.

People are concerned that they will have insufficient resources. When people are asked to change, they often think they need additional time, money, facilities, and personnel. But the reality today is that they will have to do more with less. Organizations that have downsized have fewer people around, and those that are around are being asked to accept new responsibilities. They need to work smarter, not harder. Rather than providing these resources directly, leaders must help people discover their own ability to generate them.

People can handle only so much change. Beyond a few changes—or even only one, if the change is significant—people tend to get overwhelmed and become immobilized. That’s why it’s probably not best to change everything all at once. Choose the key areas that will make the biggest difference.

In the SAP implementation mentioned earlier, what personal concerns were expressed, and how were they addressed? In interviews, people said: “I saw the databases yesterday and realize I don’t have to do anything right now. It’s less intimidating now that I’ve been able to play with it a little. I’m worried about the timing—the ‘go live’ date is in the middle of everything else. It will definitely take more time. I’m concerned that it will be hard to learn and use. I don’t think my team leader can speak for us. She doesn’t have a good enough view of our day-to-day work. I hope there will be one-on-one support, because the training won’t create the sense of security I’ll need to be able to use the system confidently. If things run smoother, what will we do with our time? We have to answer the question ‘What does this mean for me?’ now. I can’t do this and my real job at the same time. When this project is over, I’ll have to go back and fix everything else.”

The SAP change leadership team in this company set up forums for people to express their personal concerns, and then systematically worked at providing responses to questions about timing, involvement, support systems, and managing multiple priorities.

Once people feel that their personal concerns have been heard, they tend to turn their attention to how the change will really shake out. These are called implementation concerns.

Stage 3: Implementation Concerns

At this stage, people ask questions about how the change will be implemented. For example: What do I do first, second, third? How do I manage all the details? What happens if it doesn’t work as planned? Where do I go for help? How long will this take? Is what we are experiencing typical? How will the organization’s structure and systems change?

People with implementation concerns are focused on the nitty-gritty—the details involved in implementing the change. They want to know if the change has been tested. They know the change won’t go exactly as planned, so they want to know, “Where do we go for technical assistance and solutions to problems that arise as the change is being implemented?” People with implementation concerns want to know how to make the best use of information and resources. They also want to know how the organization’s infrastructure will support the change effort (the performance management system, recognition and rewards, career development).

In the SAP implementation mentioned earlier, implementation concerns such as these were voiced: “I’m concerned that people will hold onto their pet systems. Some other applications may survive, and we’ll end up with redundant systems. We don’t have the hardware to run the software. I’m concerned that there won’t be enough time to clean up the data or verify the new business processes we’ve designed. I want to touch it now, sooner rather than later. We need more information about what we can expect and when we can give suggestions. I could really use a timeline—what I’ve seen has been too detailed or too sparse. I need to know when I’ll be involved/crunched. Will people really be held accountable for using the new system?”

These implementation concerns were best addressed when the people closest to the challenges of implementing the change were involved in planning the solutions to the problems that were surfaced.

Stage 4: Impact Concerns

Once the first three stages of concern are lowered, people tend to raise impact concerns. For example: Is the effort worth it? Is the change making a difference? Are we making progress? Are things getting better? How?

People with impact concerns are interested in the change’s relevance and payoff. The focus is on evaluation. This is the stage where people sell themselves on the benefits of the change based on the results being achieved. This is also the stage where leaders lose or build credibility for future change initiatives. If the change doesn’t positively impact results—or if people don’t know how to measure success—it will be more difficult to initiate and implement change in the future. Conversely, this is the stage where you can build change leaders for the future if you identify the early adopters and recognize their successes with the change

Stage 5: Collaboration Concerns

People at the fifth stage of concern ask questions about collaboration during the change. For example: Who else should be involved? How can we work with others to get them involved in what we are doing? How do we spread the word?

People with collaboration concerns are focused on coordination and cooperation with others. They want to get everyone on board because they are convinced the change is making a difference. During this stage, get the early adopters to champion the change and influence those who are still on the fence.

Stage 6: Refinement Concerns

People at this stage ask questions about how the change can be refined. For example: How can we improve on our original idea? How can we make the change even better?

People with refinement concerns are focused on continuous improvement. During the course of an organizational change, a number of learnings usually occur. As a result, new opportunities for organizational improvement often come to the surface at this stage.

Impact, collaboration, and refinement concerns were barely audible in our SAP example, since it was still being planned. But we heard the following: “We expect a drop in productivity when we go live. We have to begin to define who owns which work processes and who upstream/downstream needs to change when we go live. SAP isn’t just the implementation of new technology; it’s business process redesign. We have to build the linkages and do the data conversions now. The experienced SAP users in the company haven’t been tapped. I’m concerned we’ll ship late when we make the conversion. Exceptions to usual flows are not being anticipated. Old-timers won’t be able to take the shortcuts they are used to. Real-time processing will help us eventually, but at first it will add time. It’s important to be thinking about integration across all processes now. I’m sure things will get worse in the first few weeks. What will the next phases focus on?”

We’ve learned that when people have refinement concerns with one change, they often are hatching the next change. The more you involve others in looking at options and in suggesting ways to do things differently, the easier it will be to build the business case for the next round of change.

While dealing with people’s concerns about change may seem like a lot of hand-holding, each stage of concern can be a major roadblock to the change’s success. Since the stages of concern are predictable and sequential, it is important to realize that, at any given time, different people are at different stages of concern. For example, before a change is announced, the leaders of the change often have information that others in the organization don’t. In addition, these change leaders typically have figured out how the change will affect them personally and even have gone so far as to formulate an implementation plan before others in the organization are even aware of the proposed change. As a result, the change leaders have often addressed and resolved information, personal, and implementation concerns; now they are ready to address impact concerns by communicating the change’s benefits to the organization. The rest of the organization, however, still has not had a chance to voice their concerns. As a result, they will not be ready to hear about the change’s benefits until their information, personal, and implementation concerns have been addressed.

Organizational Leadership Behaviors

If a leader can diagnose people’s stage of concern, the leader can respond by communicating the right information at the right time to address and decrease or even resolve these concerns. This requires the flexibility to respond differently to the concerns that people have going through change.

Resolving concerns throughout the change process builds trust in the leadership team, puts challenges on the table, gives people an opportunity to influence the change process, and allows people to refocus their energy on the change.

To help people resolve the questions and concerns they have at each stage of the change process, it is most helpful to respond with the right combination of focusing (directive) and inspiring (supportive) behaviors. When you do so, the questions are answered, and people are prepared to move to the next stage of change. Not addressing the questions holds people back and delays, if not stops, the process of moving forward.

Focusing and inspiring behaviors are like directive and supportive behaviors in the Situational Leadership® II model as it’s used with individuals and teams. Initially, leaders provide the focus or direction. They often spot the gaps between what is and what could be. They “direct” the change by creating a change leadership team and by committing resources to the change. They build the business case and set up the right experiments to determine best practices for implementing the change. At each stage of the planning process, though, it’s critically important to involve others. Those impacted by the change, if involved in planning, will have vehicles to express their concerns. They will be able to work with those leading the change to inspire others to change. Let’s look a little more closely at the two behaviors in Blanchard’s organizational change leadership model.

Focusing (Directive) Behavior for Organizational Change

Behaviors that provide direction in leading organizations are primarily related to focusing energy on performance and making the change happen. These directive behaviors, when applied to change leadership, help define and prioritize the changes required of the organization. This includes explaining the business case for the change. In other words, why are we doing this? People also want to know who will be leading the change and whether they will be consulted or involved. Again, a clear vision is important here so that people can see where the organization is headed and can determine whether they fit into this picture of the future. They also want to see the implementation plan. They’ll want direction about test-driving the change. They’ll want to know how resources will be deployed. Leaders providing appropriate direction must see that the organizational structure and systems are aligned to support the desired change.

Finally, direction also involves holding everyone accountable for making the change. In successful change efforts, the responsibility for providing direction or focus is shared by a broad-based change leadership team that includes early adopters and advocates for the change from all levels of the organization.

Inspiring (Supportive) Behavior for Organizational Change

Behaviors that provide support in leading organizations are primarily related to facilitating the change process and inspiring everyone to work together. These inspiring or supportive behaviors, when applied to the organization, help demonstrate that the change leadership team is passionately committed to the change. They also make sure that people’s concerns are surfaced and heard. The key here is involvement, involvement, and more involvement. Buy-in and cooperation are increased when change leaders listen to and involve others at each step of the change process. This means sharing information broadly across the organization, asking for input, celebrating successes, and recognizing people who are changing. The best support and most inspiration are provided when leaders throughout the organization model the behaviors expected of others. When leaders walk the talk, they connect with the experience and concerns of those who are being asked to change. Connection leads to more collaboration and partnering.

Situational Leadership® II and Leading People Through Change

New work by Pat Zigarmi, Judd Hoekstra, and Ken Blanchard on the Situational Leadership® II and Leading People Through Change programs provides guidance for diagnosing concerns and then using the appropriate change leadership strategy to address those concerns. That’s where flexibility comes in, the second skill of a situational change leader. Remember, stages of concern are like stages of development at the individual and team levels.

For Information Concerns, Use a More Focusing or Directing Leadership Style

When a change is introduced, people often lack knowledge about it. They wonder what it’s all about. They have information needs: “What will we be doing differently?” People need direction and focus much more than support or inspiration. To guide the process, the change leadership team should use focusing behaviors to explain the business case for the change. It’s important to bring people face to face with data about the need to change and allow them to reach their own conclusions.

For Personal Concerns, Use a Focusing and Inspiring Leadership Style

As information is shared and knowledge increases, people realize they need to develop new skills. Anxiety increases. They want to know, “How will the change affect me personally? Will I be successful?” People still need direction and focus, but there is a growing need for support and engagement.

Leaders can help people with personal concerns about the change by providing forums for team members to say what’s on their minds. It is important at this stage to provide encouragement and reassurance. Leaders should continue to explain to team members why the change is important and provide consistent messages about the organization’s vision, goals, and expectations. They should ask people what it would take for them to see themselves as part of the future. They should create vehicles for early adopters in the organization and users of the change outside the organization to influence peer to peer. They should also provide resources that help resolve personal concerns—clear goals, time, management support, and coaching.

The outcome of the strategies that are high on focusing and inspiring behaviors is a compelling vision of the post-change future—a picture where people can see themselves succeeding.

For Implementation Concerns, Use a Focusing and Inspiring Leadership Style

After personal concerns have been dealt with, people begin to question whether enough planning has been done. They can often see what hasn’t been done quicker than the people leading the change can, because they are closer to day-to-day reality. This is the time to set up small experiments, tests, or pilots to learn what still needs to be done. This is the time to broadly involve others—asking them to flesh out a robust implementation plan with you. This is the time to go forward with resisters to learn why they are resisting (beyond personal concerns). This is the time to increase the frequency of contact between change advocates and early adopters and people who are neutral. People still need both direction/focus and support/engagement to address their implementation concerns.

Leaders can help people through this phase in the change process by working to align systems—performance planning, tracking, feedback, and evaluation systems—with the change. They can offer perspective about how long the change should take and whether performance is on track. Leaders can boost morale by walking the talk, modeling the behaviors they expect of others—openness, transparency, flexibility, responsiveness, and resilience. Leaders can also address discouragement by providing individual training and coaching, not mass training, on how to implement the change. By demonstrating that they want to listen and by responding honestly to the questions people raise, leaders build trust. At this stage, it is equally important to look for small wins, recognize progress, and share excitement and optimism about the change.

Remember that at each phase of the change process, the change leadership team includes change leaders from all levels of the organization who can respond as peers with direction and support. They can gain the cooperation of others because they can speak first-hand of their experience and success with the change.

For Impact Concerns, Use an Inspiring Leadership Style

As the third stage of concern winds down, people begin to see the payoff in using their new skills. There’s a tipping point. There’s some momentum—but only if information, personal, and implementation concerns have been surfaced and resolved and only if people have been asked to shape the change they are being asked to make. People begin to feel more confident that they will succeed. They want to know, “How are we doing on our change journey? Can we measure our progress to date?” The need for direction and focus can decline, but people continue to need support, engagement, and inspiration to let them know that progress is being made.

At this stage of the change, the change leadership team needs to collect and share information and success stories. By telling stories, they can anchor the change in the company’s culture. Working together, the change leadership team can solve problems and remove barriers or obstacles to implementing the change. It is important at this stage for leaders to encourage people to keep up their effort and desire to change.

For Collaboration Concerns, Use an Inspiring Leadership Style

When people are firmly in the final stages of the change process, they can clearly see that their efforts are paying off, and they want to expand the positive impact on others. They begin to have more ideas that they want to share with others. The question on their minds is, “Who else should be involved in our change effort?” They need very little direction and focus but continue to need support and inspiration to encourage them to use the new talents they have developed and to leverage the success they have had.

The focus now should be on encouraging teamwork and interdependence with other teams. Leaders can support the change by cheerleading the improvements in the team’s performance and encouraging people to take on even greater challenges.

For Refinement Concerns, Use an Inspiring Leadership Style

The destination is now in sight. People know new ways to behave and how to work in the changed environment. They are ready to ask questions such as “Can we identify new challenges and think of new ways to do things? Can we leverage what we’ve done so far?” The need for both direction/focus and support/inspiration is declining. This is where integration of everything they have learned during the change journey occurs.

Team members and leaders at this point need to support continuous improvement and innovation throughout the organization. They should encourage each other to continue to challenge the status quo and to explore new options and possibilities.

The more that people throughout the organization are involved in talking about options and possibilities, the easier it will be to build the business case for the next round of change.

Involvement and Influence in Planning the Change

As we have emphasized, once the change leadership team has diagnosed people’s stages of concern, they must learn to flexibly use the appropriate change leadership strategy and corresponding behaviors to address the specific concerns people have in each stage of organizational change. Doing so significantly increases the probability of implementing successful change, because it creates a partnering for performance environment that expands opportunities for involvement and influence.

When leaders expand people’s involvement and influence during a change, there is more buy-in for the change, because people are less likely to feel they are being controlled. When leaders expand opportunities for involvement and influence, they get a chance to hear people’s concerns. When they’ve heard the concerns, they can often resolve them. This builds trust and increases the credibility of the change leadership team.

In this chapter, we have focused on how to use the Situational Leadership® II model to lead organizational change. We have shown how all three skills of a situational leader—diagnosis, flexibility, and partnering for performance—play out in leading people through change. We have also focused on the first three Predictable Reasons Why Change Efforts Typically Fail. In the next chapter, we introduce the Leading People Through Change model, which defines nine change leadership strategies. This will be helpful for overcoming the remaining reasons on the list of Why Change Efforts Typically Fail.